Abstract

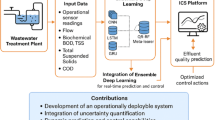

Access to clean water is one of the most critical challenges facing modern society, especially as rapid urban growth, industrial expansion, and population pressures continue to strain water resources. In light of these growing concerns, Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) represents a global pledge to ensure clean water and sanitation for all. Central to achieving this goal are Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs), which require reliable tools to monitor and predict water quality parameters for better management and compliance. This study presents an innovative deep learning framework built on Transformer-based architectures to address this challenge. First, introduce TransGAN, a Transformer-driven Generative Adversarial Network designed to produce high-fidelity synthetic tabular data, helping to overcome the common issue of limited training data in WWTP systems. Next, propose TransAuto, a dual-purpose Transformer Autoencoder capable of detecting anomalies and identifying key features in complex multivariate time series data—two crucial tasks for ensuring data quality and interpretability. To enhance predictive performance, multiple Transformer-based architectures were explored. The Time Series Transformer (TST), a streamlined variant of the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) that integrates Variable Selection Networks (VSN) and Gated Linear Units (GLU), demonstrated superior accuracy among single-model approaches. In addition, the pretrained TimeGPT model was evaluated for its ability to capture complex temporal dynamics, offering valuable performance benchmarks. For further performance gains, an ensemble learning model that stacks three state-of-the-art Transformers: Informer, Autoformer, and FEDformer. Empirical results demonstrate strong performance: TST achieved MSE of 0.0028 and R2 of 0.9643, while the ensemble model reached an MSE of 0.0036, RMSE of 0.0582, MAE of 0.0438, and R2 of 0.9646. These outcomes highlight the effectiveness of Transformer-based models in accurately forecasting wastewater quality and support their use in real-world water management applications, aligning strongly with the goals of SDG 6.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is at the heart of life, shaping everything from food production to the industries that drive economies. A large share of freshwater is dedicated to agriculture, making irrigation essential for food security. But despite water’s life-giving properties, its scarcity and contamination remain pressing concerns1. Millions of people still struggle to access clean drinking water and proper sanitation, exposing them to serious health risks. As cities grow and industries expand, the demand for water continues to rise, placing immense pressure on already stretched resources2. Meanwhile, excessive groundwater extraction to meet agricultural and urban needs is depleting reserves at an alarming rate, pushing many regions to the brink of crisis. Climate change further intensifies these challenges, causing erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts, and devastating floods that disrupt water availability and threaten ecosystems.

Addressing today’s environmental pressures requires sustainable water management, and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 highlights the importance of ensuring clean water and sanitation for all3. Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are central to this effort, as they recycle and purify wastewater, cut down on pollution, and make water resources more sustainable4. Effective treatment and reuse not only protect ecosystems but also improve public health and community well-being. To achieve these outcomes, industries are turning to both Effluent Treatment Plants (ETPs) and Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) to manage different wastewater streams and move toward Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD)5. Beyond traditional uses such as gardening or industrial cooling, properly treated wastewater can also serve domestic and agricultural purposes, offering a practical solution to water scarcity and promoting efficient resource use 6. Industrial wastewater management often relies on laboratory-based methods and real-time sensors for water quality assessment. While these methods are precise, they can be expensive, time-consuming, and difficult to maintain on a large scale7.

To enhance efficiency, AI-driven technologies are emerging as transformative solutions. By integrating Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) with conventional methods, wastewater treatment can be optimized through real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, and automated decision-making8. These advanced approaches enable industries to analyze complex water parameters, improve treatment efficiency, reduce operational costs, and ensure compliance with environmental standards. By embracing AI-driven solutions, industries can contribute significantly to SDG 6, ensuring sustainable water management and promoting a future where clean water remains accessible and reusable9.

Accurate prediction of water quality parameters is essential for safeguarding the environment and optimizing wastewater treatment processes. Traditional Machine Learning (ML) approaches, which rely on statistical and rule-based analyses, provide valuable insights but often struggle as datasets become larger, more complex, and time-dependent10. Deep Learning (DL) techniques, particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), address these challenges by automatically learning intricate feature representations from raw data, resulting in improved predictive accuracy11. For temporal modeling, architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)12, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks13, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) capture sequential dependencies14, allowing effective analysis of water quality variations over time. Nevertheless, the sequential nature of these models can limit computational efficiency and their ability to capture long-range dependencies15. Transformer-based models have emerged as a powerful alternative, overcoming these limitations through self-attention mechanisms that process entire sequences simultaneously16 This enables them to model long-range interactions and complex relationships between multiple parameters, making them highly suitable for long-term trend analysis and forecasting17.

Giacomo et al18 use a Time Series Transformer to efficiently predict spatial dynamics in a methanol reactor, offering fast, accurate results compared to traditional solvers. Cerrone et al. 19 integrate the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) with NOAA’s STOFS-2D-Global model to enhance 7-day ocean water level forecasts. The TFT refines hydrodynamic outputs by correcting biases, especially in wind- and tide-dominant coastal regions, using relevant covariates. Subbotin et al.20 show that TimeGPT outperforms Time-LLM and MSET in forecasting car telematics, with higher accuracy and slightly longer processing time—offering strong potential for safer, smarter vehicle systems. Qi Li et al.21,22 use a dual-channel setup combining Informer and TCN to enhance wind power forecasts, effectively capturing complex patterns and outperforming traditional methods. Yang et.al23,24 present MG-Autoformer, a streamlined transformer model for long-term power load forecasting that captures both short- and long-term patterns using multi-granularity attention and a shared Q–K structure25 .present a hybrid model that merges DA-FEDformer and multi-model error correction to forecast carbon prices. This frequency-enhanced transformer approach yields highly accurate results across key Chinese markets. Inspired by these advances, transformer-based models are now being widely used to forecast water quality parameters. Their strength lies in capturing intricate temporal patterns and long-term dependencies, enabling more precise and dependable predictions than traditional techniques26. By effectively managing the complex and nonlinear behavior of water quality data, these models play a key role in enhancing the monitoring and management of aquatic ecosystems.

Despite these advancements, several research gaps remain in industrial wastewater management. Most existing studies focus on single-parameter predictions, short-term forecasting, or environmental datasets, leaving multi-parameter, long-term predictions for industrial wastewater largely unexplored. Furthermore, the integration of AI-driven models for real-time monitoring, anomaly detection, and operational decision-making in wastewater treatment plants is still limited, highlighting opportunities for innovation.

To address these gaps, this study introduces a unified deep learning framework tailored for wastewater treatment systems. At its core, TransGAN generates high-quality synthetic tabular data to overcome scarcity, while TransAuto, a Transformer-based autoencoder, enables robust anomaly detection and feature identification. Temporal dynamics are modeled using a combination of Time Series Transformer (TST), Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) enhanced with Variable Selection Networks (VSN) and Gated Linear Units (GLU), and pretrained TimeGPT, capturing both short- and long-term dependencies. To further improve predictive performance, a stacked ensemble of Informer, Autoformer, and FEDformer is employed, delivering state-of-the-art accuracy for water quality parameter forecasting. This integrated pipeline goes beyond isolated model use seen in earlier studies—offering a scalable, intelligent solution for real-world wastewater monitoring and aligning directly with SDG 6. Key highlight of the work as follows:

-

Developed TransGAN, a Transformer-based GAN for generating realistic synthetic data for wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs).

-

Proposed TransAuto, a Transformer Autoencoder for unsupervised anomaly detection and feature importance analysis.

-

Utilized time series transformer (TST), Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) with VSN and GLU, and pretrained TimeGPT for precise temporal modeling of wastewater quality.

-

Proposed predictive performance with a stacking ensemble of Informer, Autoformer, and FEDformer models.

-

Demonstrated a complete Transformer-based framework for forecasting and monitoring wastewater quality.

-

Supports Sustainable Development Goal 6 by enabling intelligent, data-driven decisions in wastewater treatment and management.

Data source and preprocess

Working of industrial STP

The raw data used in the study pertains to an STP of a chemical industry (Fig. 1). The overview of how a WWTP functions, structured across three main stages: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Treatment. Each phase is tailored to progressively clean the wastewater and ensure it meets quality standards for discharge or reuse. Firstly, during the Primary Treatment, the incoming wastewater undergoes initial chemical conditioning. Chemicals from the Alkali Dosing Tank and PAC Dosing Tank are introduced to regulate pH and aid in coagulation. This chemically treated water flows into a Buffer Tank, which equalizes flow variations, and then into a Flash Mixer to ensure rapid and uniform blending of chemicals. The mixed solution is directed to the Settling Tank (25kl) where suspended solids settle at the bottom. This stage is essential for removing larger particulates, which reduces the load on downstream biological processes.

Secondly, the Secondary Treatment begins, shifting the focus from physical–chemical to biological purification. The water first enters the Anoxic Tank, where low-oxygen conditions enable the removal of nitrogen through denitrification. It then moves into two Aeration Tanks (40kl and 120kl), where oxygen is supplied to support microorganisms that digest organic pollutants. After biological degradation, the water flows into the Clarifier (30kl) to separate the biomass from the treated liquid. The cleaner water is collected in the Clarifier Outlet Tank (20kl). This stage plays a critical role in reducing biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and nutrient levels. Thirdly, the Tertiary Treatment acts as the final polishing step. Water is passed through an Ozonation System for oxidation and disinfection, and then filtered using Pressure Sand Filter (PSF) and Activated Carbon Filter (ACF) to eliminate fine particles and trace organics. It is temporarily stored in the UF Feed Tank (20kl) before being treated in an Ultra Filtration System. Lastly, a UV System ensures microbial disinfection before the treated water is collected in the Outflow Tank (60kl). Throughout the system, Sampling Points (SP) are strategically placed to monitor performance and ensure compliance with environmental regulations. Together, these stages form a comprehensive, step-by-step process for producing safe and reusable effluent.

Dataset description and its analysis

Data for this study is gathered daily using advanced laboratory instruments, capturing the ever-changing dynamics of the wastewater treatment process. It includes detailed measurements of 21 key features with 1064 data samples, representing both influent and effluent characteristics, as well as overall treatment performance. While laboratory analysis offers high accuracy, it comes with limitations—being time-intensive, costly, and often resulting in delayed access to critical data. To overcome these challenges, the proposed model offers early and reliable predictions of important parameters, minimizing the reliance on slow lab-based testing. This predictive capability not only streamlines day-to-day operations and maintenance but also helps reduce energy usage, ultimately boosting the efficiency, responsiveness, and sustainability of the entire wastewater treatment system (Fig. 2).

The box plot analysis offers a clear picture of how the different parameters in the STP dataset behave in terms of distribution, variability, and the presence of outliers. The influent stage shows significant fluctuations, with particularly high average values for CODIN (2141.19 mg/L, std 802.82), BODIN (900.60 mg/L, std 293.25), and AmmoniaNitrogenIN (115.93 mg/L, std 53.37), pointing to heavy organic and nutrient loads entering the system. Parameters such as TSSIN (1082.30 mg/L, std 568.79) and ConductivityIN (7354.31 µS/cm, std 3676.08) also reveal wide dispersion, indicating inconsistency in the quality of raw wastewater. In contrast, operational conditions within the plant appear more stable, as seen in PHAR (6.92, std 0.21) and DOAR (3.71 mg/L, std 2.06), which suggest that biological treatment processes are maintained under favorable ranges. Effluent data highlight the plant’s effectiveness, with BODOUT (4.82 mg/L, std 1.18) and CODOUT (31.87 mg/L, std 13.87) showing sharp reductions relative to influent values. Likewise, TSSUFI (21.87 mg/L, std 5.61) and TurbidityUFI (8.41 NTU, std 3.91) remain at low levels, demonstrating efficient solid–liquid separation. Across all stages, pH remains tightly controlled, underscoring the stability of the treatment process. Taken together, the plots confirm that although influent quality is highly variable and includes several outliers, the STP consistently delivers strong reductions in organic load, suspended solids, and turbidity, reflecting reliable and robust treatment performance.

High-fidelity synthetic data generation using transformer _generative adversarial network (TransGAN)

TransGAN is a Transformer-based generative adversarial network designed to produce high-quality tabular data. Unlike traditional GANs that typically use convolutional or recurrent layers—methods better suited for images or sequential inputs—TransGAN builds on the attention mechanism of Transformers. This approach enables the model to capture complex, long-range dependencies and interactions among features without assuming any spatial or sequential structure. Such adaptability is particularly valuable for tabular datasets, where variables are highly interdependent but not ordered in a fixed way. By effectively modeling these intricate relationships, TransGAN generates synthetic data that closely mirrors the statistical patterns and dependencies of real-world datasets 27.

In the TransGAN design, the generator begins with random noise, passes it through dense layers, and then through stacked Transformer layers, which progressively refine feature interactions. To ensure the outputs remain well-scaled, the model applies power and range normalization before mapping the results to the target distribution using a tanh activation 28. The discriminator follows a similar structure, reshaping both real and generated data and using Transformer blocks to detect even subtle inconsistencies in distribution. Training is anchored in adversarial loss, where the generator tries to fool the discriminator while the discriminator sharpens its ability to spot fakes. Beyond this core mechanism, the proposed TransGAN introduces stabilizing components— mean–variance alignment to maintain consistent scaling, quantile-based penalties to preserve distribution shapes, gradient regularization to prevent unstable updates, and label smoothing to reduce sharp decision boundaries29 The quality of synthetic data is evaluated using metrics such as Mean Error, Standard Error, Wasserstein Distance, Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) statistic, and KL Divergence, which verify alignment with the real data distribution30. With these validations and stability enhancements, the TransGAN generates statistically consistent, high-quality synthetic tabular datasets (Fig. 3).

The transformation begins by passing the input vector x through a dense layer (Dense \((x)={W}_{1}x+{b}_{1})\), which maps it into a higher-dimensional feature space. This step enhances the representational capacity of the model and prepares the data for subsequent processing in the transformer block. The next stage employs a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) mechanism, which is designed to capture complex dependencies between different parts of the input sequence. In this process, the transformed input is projected into query (Q), key (K), and value (V) vectors through learned weight matrices. Multiple attention heads (\({MAH}_{i}\)) operate in parallel, allowing the model to learn diverse relationships from different representation subspaces. The attention for each head is then computed as shown in Eq. (1).

The outputs from all heads are then concatenated and linearly projected with WO to form the final output \(MHSA=Concat({MAH}_{1},{MAH}_{2},\dots ,{MAH}_{n}){W}_{o}\), This mechanism allows the model to attend to information from multiple perspectives, improving its ability to model complex dependencies across features.

The generator block begins by drawing a random noise vector Z from a standard normal distribution (\(Z\sim N(0,I)\)) using a weight matrix \({\text{W}}_{1}\) (Eq. 2). This vector is then passed through a dense layer, \({\text{W}}_{2} and bias {\text{b}}_{2}\) series of Transformer blocks, allowing the model to learn complex feature relationships31. The final output is mapped through a \(tanh\) activation, ensuring the generated data \({x}_{fake}\) stays within a normalized range.

The discriminator block takes an input (real or fake), processes it through transformer layers, and outputs a probability score using a function σ, indicating how likely the input is real (Eq. 3).

The adversarial loss defined in (Eq. 4), where the discriminator loss (\({\text{L}}_{D}\)) drives the model to differentiate real data from generated data, and the generator loss (\({\text{L}}_{G}\)) trains the generator not only to deceive the discriminator but also to minimize the difference between real and generated samples through the reconstruction term (\({\parallel {\text{x}}_{real}-\text{G}({\text{x}}_{fake})\parallel }^{2}\))32. This reconstruction component preserves data fidelity by ensuring synthetic outputs remain structurally consistent with real samples. The weighting factor λ is a constant hyperparameter, tuned experimentally, that balances adversarial learning against reconstruction accuracy, preventing either objective from dominating the training process.

TransGAN are powerful in understanding intricate, non-linear patterns within data thanks to their self-attention mechanism. This allows them to extract more meaningful and expressive latent features, resulting in highly accurate reconstructions and the generation of diverse, realistic synthetic samples. TransGAN tend to be resource-intensive, often needing more memory and longer training times than traditional models33,34. They’re also more prone to overfitting when working with smaller datasets and can be quite sensitive to how their hyperparameters are configured.

Dual-purpose transformer_autoencoder for robust anomaly detection and feature importance analysis (TransAuto)

The TransAuto model combines the encoder–decoder structure of the Transformer with an autoencoder framework, making it well-suited for capturing complex temporal and multivariate patterns. Within the context of WWTP datasets, the architecture is designed to address two complementary but distinct objectives: identifying anomalies in the input data and selecting the most relevant features for analysis35. As shown in Fig. 4, the overall framework is organized into three main components: the Transformer-based Autoencoder, the Anomaly Handling Block, and the Feature Selection Block.

The process begins with Attention Block, where multi-head self-attention (MHA) is applied to capture complex relationships among the input features. Instead of focusing on a single dependency, MHA allows the model to examine the data from multiple perspectives at once. Each attention head highlights different types of interactions, and their combined output provides a balanced and comprehensive representation of the dataset36. The outputs from the attention mechanism are then passed into the MLP Block, which consists of fully connected layers with integrated dropout regularization. In addition, early stopping was applied to help the model remain robust against noise. This design refines the feature embeddings while reducing the risk of overfitting, ultimately producing robust latent representations. These representations are then processed in the Autoencoder Block, which follows a standard encoder–latent space–decoder structure. The encoder compresses the high-dimensional input into a compact representation, and the decoder reconstructs the original inputs. Through this reconstruction process, the model learns the underlying distribution of normal operating patterns in the data37.

After training, anomaly detection is carried out in the Anomaly Handle Block. Reconstruction errors are calculated as the mean squared difference between the original inputs and their reconstructed counterparts:

In Eq. 5, each input sample \({x}^{\left(i\right)}\) is compared to its corresponding reconstructed version \({\widehat{x}}^{\left(i\right)}\). If the reconstruction error for a given sample exceeds a learned threshold, that sample is flagged as anomalous. The threshold is optimized through grid search and is typically chosen to prioritize sensitivity while minimizing false positives38 . Instead of discarding anomalies, the model corrects them by replacing their values with reconstructed estimates, producing a cleaned dataset that maintains both consistency and reliability for further analysis.

The cleaned dataset is then used for feature selection. Two complementary strategies are employed. The first is Attention-Based feature importance, in which attention weights are aggregated across samples, normalized, and ranked to highlight features that consistently attract the model’s focus. The second is Reconstruction Error-Based feature importance, where each feature is masked one at a time and reconstruction error is recalculated39. The increase in error relative to the baseline indicates the importance of the masked feature. Masking is particularly well aligned with the autoencoder framework, as it directly evaluates each feature’s contribution to accurate reconstruction. To obtain a unified measure of importance (j), the attention-based and reconstruction-based scores are combined into a single normalized value (Eq. 6):

The resulting scores are then ranked by the Feature Importance Ranker, which selects the top-N most informative features. This process reduces dimensionality and noise while retaining the key variables needed for interpretation. By integrating anomaly detection and feature selection within a single architecture, it simplifies the modeling workflow and reduces the need for multiple independent models. The self-attention mechanism enhances interpretability by uncovering complex relationships across features, while the anomaly handling block improves data quality by replacing irregular values with informed estimates rather than discarding information40. The primary limitation, however, lies in its computational intensity, particularly when applied to large-scale datasets.

Methods and methodology

Transformers, first introduced for natural language processing tasks, are now making significant strides in time series analysis, particularly in monitoring water quality. These models are well-suited for handling the sequential nature of water quality data, where variables are recorded over time at regular intervals41. What sets Transformers apart is their self-attention mechanism, which enables the model to assess and prioritize different time points in the sequence. This capability allows them to capture both short- and long-term dependencies more effectively than traditional methods such as ARIMA or even recurrent models like LSTMs. As a result, recent research demonstrates that Transformer-based models can effectively capture complex dynamics in time series data, including long-term trends, recurring seasonal patterns, and sudden structural changes42.

Time series transformer model (TST)

Time Series Transformer (TST) is a neural architecture tailored for forecasting sequential data, such as water quality indicators, by capturing complex temporal dependencies. The process begins by mapping the raw input sequence into a higher-dimensional space through a linear projection layer. To preserve the ordering of time steps, learnable positional encodings are added to these representations 43. The resulting sequence is then processed by a stack of encoder layers, each combining multi-head self-attention with feedforward MLP blocks. This design allows the encoder to extract meaningful patterns and long-range dependencies across the time series. The encoder output, often referred to as “memory,” is provided to the decoder, which generates forecasts in an autoregressive fashion—each new prediction depends on the outputs generated so far 44. Decoding begins with a learned start token that serves as a placeholder for the first step. During training, the decoder is guided using teacher forcing, where the actual observed target values are embedded and appended to the sequence after the start token. This approach prevents error accumulation, stabilizes training, and accelerates convergence. During inference, true future values are unavailable, so the decoder auto-regressively feeds its own previous predictions back as inputs to generate subsequent forecast steps45. Within the decoder, masked self-attention ensures predictions are conditioned only on previous outputs, while cross-attention leverages the encoder’s memory to refine and align the generated forecasts.

Finally, the decoder produces a representation for the next time step, and this output is passed through a small feedforward network consisting of linear layers, a ReLU activation, and dropout. This final stage reduces the high-dimensional representation down to a single prediction value—typically the forecasted value for the next time point 46. This entire process aligns with the architecture diagram, flowing from input embedding to attention layers, and ending with a dense output (Fig. 5).

In the input stage, the raw sequence X∈\({R}^{\text{batch}(\text{b})\times \text{seq}(\text{T})\times \text{input}\_\text{dim}({\text{d}}_{in})}\) is first transformed into a higher-dimensional representation. This is achieved by a linear projection followed by the addition of positional information:

In Eq. (7), \({\text{W}}_{\text{in}}\in {R}^{{\text{d}}_{in}\times {\text{d}}_{model}}\) and \({\text{b}}_{\text{in}}\in {\text{R}}^{{\text{d}}_{\text{model}}}\) expand the feature space, while \(P\in {R}^{1\times T\times {d}_{model}}\) provides learnable positional encodings. This positional term is essential because the Transformer architecture itself is insensitive to sequence order. Writing the input stage as \(Proj\left(\text{X}\right)+\text{P}\) highlights that temporal structure is injected after feature projection, ensuring the model recognizes the order of time steps.

Once this enriched representation is formed, it enters a stack of Transformer encoder layers. Each encoder layer contains two main components: a multi-head self-attention mechanism (formally defined in Eq. 1) and a feed-forward block. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to evaluate dependencies across different time steps, capturing both short- and long-range temporal patterns in the sequence. Following attention, the output is processed by a position-wise feed-forward network:

In Eq. 8,\(z\in {R}^{B\times T\times {d}_{model}}\), \({\text{W}}_{1}\in {R}^{{d}_{model}\times {d}_{ff}}\) , \({\text{W}}_{2}\in {R}^{{d}_{ff}\times {d}_{model}}\) and the biases are broadcast over the sequence length. The activation function ϕ (⋅) (ReLU) is applied before the second linear transformation, as indicated by parentheses, making the evaluation order explicit47 This non-linear mapping enriches the representation and enhances the model’s ability to capture complex temporal features. To maintain stability across stacked layers, each attention and feed-forward sublayer is wrapped with residual connections and layer normalization to prevent gradient vanishing or explosion problem. After passing through the encoder, the decoder processes the encoded memory and autoregressively generates outputs. The final step involves mapping decoder states \(z\in {R}^{B\times {T}{\prime}\times {d}_{model}}\) into the target space using an output projection layer

In Eq. 9, \({\text{W}}_{out1}\)∈ \({R}^{{d}_{model}\times {d}_{hid}}\) , \({\text{W}}_{out2}\)∈ \({R}^{{d}_{hid}\times {d}_{target}}\) and associated biases are uniquely defined to avoid overlap with encoder parameters. This projection translates the latent decoder representation into the final prediction space, completing the sequence generation process 48. While this architecture effectively captures complex, long-range patterns through self-attention, it comes with high computational costs and typically demands large training datasets to perform well.

Simplified version of temporal fusion transformer (TFT) using variable selection network (VSN) and gated linear unit (GLU)

The TFT is a deep learning architecture specifically designed for time series forecasting. Its strength lies not only in modeling temporal patterns but also in identifying the most relevant features at each point in time, making it both sequence-aware and feature-selective. The process begins with the VSN, which functions as an adaptive filter that scans all available input features and assigns dynamic importance scores to them49. Instead of removing features entirely, it continuously adjusts their contribution so that the model emphasizes what is most relevant at each step. After feature selection, the inputs move into a projection layer that transforms them into a higher-dimensional space, enriching their representation and allowing the model to capture more complex relationships. This is followed by positional encoding, where learnable signals are added to provide information about the order of time steps. Since neural networks do not inherently recognize sequence or time, these encodings supply essential temporal context for accurate forecasting50.

At the core of the TFT are temporal attention layers built on multi-head self-attention mechanisms. These layers scan across different time points and assign importance to past information based on its relevance to the prediction task. This enables the model to determine which historical signals should influence the forecast and when they matter most. To support stable and efficient training, the attention layers incorporate residual connections and layer normalization, which preserve gradient flow and accelerate convergence. The refined representations are then processed by GLUs, which act as adaptive gates that selectively pass useful information while filtering out less relevant signals, ensuring a streamlined flow through the network51. Finally, the outputs are directed into a fully connected layer that consolidates all processed information into the final prediction, typically a single value representing the target variable at the forecasted time step (Fig. 6).

The VSN plays a central role in the TFT by identifying the most relevant input features at each time step. It assigns soft attention weights (\({\alpha }_{i}\)) to individual features, which are each passed through a small neural network \({\text{f}}_{i}(\text{x})\). The weighted combination of these outputs forms the selected input, allowing the model to emphasize informative signals while filtering out noise. This mechanism not only improves predictive accuracy but also enhances interpretability (Eq. 10).

To capture temporal dependencies, the model incorporates temporal attention, which highlights the most influential time steps based on their relative importance. As defined in Eq. 1, the attention mechanism generates context-aware representations of the sequence. Multi-head attention further extends this process by running multiple attention operations in parallel, enabling the model to detect diverse temporal patterns. This design significantly strengthens the ability of TFT to capture complex, long-range dependencies in time series data.

In addition, GLUs act as adaptive filters within the architecture (Eq. 11). By applying a sigmoid-based gating function (\(\upsigma )\) to a linear transformation of the input (x), GLUs determine how much information should be retained or suppressed (learnable weights \({\text{W}}_{\text{x}}\) and bias \(b)\). This dynamic control over information flow enhances the robustness and efficiency of the model, ensuring that only the most useful signals are propagated forward52.

Pretrained TIMEGPT for time-series

TimeGPT is a deep learning model tailored for time series forecasting, combining the sequential learning strength of LSTMs with the contextual awareness of Transformer attention. The process begins by projecting raw input features into a higher-dimensional latent space, where each feature is represented more richly to capture complex, nonlinear patterns. To preserve the order of events, learnable positional embeddings are introduced, embedding temporal information directly into the sequence 53. The sequence is then passed through stacked LSTM layers, which model temporal dependencies and retain essential historical information. A multi-head attention mechanism follows, allowing the model to identify the most influential time steps and balance both local patterns and long-range dependencies. Rather than focusing only on the final time step, TimeGPT applies global average pooling across all time steps, creating a unified representation by averaging contributions throughout the sequence. This prevents over-reliance on recent observations and ensures that the full temporal context is considered33. The pooled vector is finally processed through dense layers with nonlinear activations and dropout, producing the forecast. By integrating sequential memory, attention-driven context, and balanced pooling, TimeGPT effectively captures both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends, making it highly suitable for complex forecasting tasks (Fig. 7).

The foundation of TimeGPT lies in the LSTM network, a variant of recurrent neural networks specifically designed to capture both short- and long-term dependencies in sequential data. Information flow is controlled through a cell state and three gating mechanisms. The forget gate determines which information from the past should be discarded:

In Eq. 12, \({h}_{t-1}\) is the previous hidden state, \({x}_{t}\) is the current input, and σ denotes the sigmoid activation. While the input gate (\({i}_{t})\) and candidate cell (\({\widetilde{C}}_{t})\) states regulate the addition of new information (Eq. 13) :

The updated cell state is expressed as \({C}_{t}={f}_{t}\odot {C}_{t-1}+{i}_{t}\odot {\widetilde{C}}_{t}\), here ⊙ representing element-wise multiplication. Finally, and the output gate generates the next hidden state (Eq. 14):

This structure helps LSTMs capture both short-term and long-term dependencies, making them powerful for time series prediction. TimeGPT blends the strengths of LSTM and Transformer architectures by applying multi-head self-attention (defined in Eq. 1) after sequential LSTM layers 54. To form the final sequence representation, TimeGPT employs global average pooling across all hidden states:

where T denotes the sequence length in Eq. 15. This approach balances contributions from all time steps, ensuring that predictions do not overemphasize the most recent observations. The pooled representation is subsequently passed through fully connected layers with nonlinear activations and dropout to produce the forecast. By uniting the sequential memory of LSTMs, the contextual power of attention, and the balanced aggregation of global average pooling, TimeGPT provides a robust framework for modeling both local variations and long-range temporal dynamics55. The inclusion of attention mechanisms increases computational cost, especially for long sequences, which can impact training time and resource efficiency.

An ensemble of informer, autoformer, and fedformer for enhanced time series prediction

The proposed ensemble model integrates multiple transformer-based architectures to achieve more resilient and accurate time series forecasting. The process begins with an input projection layer that prepares raw sequence data for analysis, followed by three specialized attention mechanisms—Informer, Autoformer, and FEDformer—that each emphasize different temporal dynamics. Informer efficiently captures long-range dependencies using sparse attention23,24. Autoformer decomposes sequences into seasonal and trend components for structured representation56 and FEDformer enhances accuracy by extracting frequency-domain patterns57. To leverage their complementary strengths, the outputs are integrated through a hybrid ensemble strategy that combines voting, weighted averaging, and stacking. While voting and averaging directly merge base model predictions, stacking incorporates an additional meta-learner (LinearRegressor) to optimally fuse outputs. This two-stage framework enables base models to capture diverse representations, which are then refined through the ensemble integration layer. The final stage applies a feed-forward network with Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) activation, smoothing and refining the signal before producing the forecast. By blending multiple architectures with staged ensemble learning, the model improves robustness and predictive accuracy, as demonstrated in Fig. 8.

The Frequency Enhanced Attention (FEA) mechanism, used in the FEDformer model, brings a new twist to the Transformer architecture by tapping into frequency domain features. Instead of relying solely on self-attention to understand time-series data, FEDformer transforms the input using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). This helps it pick out dominant frequency components—like repeating patterns or cycles—and apply specialized transformations to them 58. The result is then blended with a linear projection of the original input. This combination lets the model better grasp both short-term details and long-range periodic trends, addressing some of the weaknesses traditional Transformers face when working with complex temporal data.

In Eq. 16, \({x}_{n}\) denotes each element in the input time-series of total length N, with n serving as the index for each time step. The result F(x), represents the kth frequency component after applying the Discrete Fourier Transform, capturing how strongly that particular frequency is present in the original signal. The term \({e}^{-2\pi ikn/N}\) is a complex exponential that serves as a frequency-selective basis function, allowing the transformation to isolate specific oscillatory patterns. Here, ‘i’ is the imaginary unit, enabling the formula to represent both the amplitude and phase of each frequency component.

Informer, on the other hand, tackles the computational inefficiency of standard attention mechanisms with a clever idea: it uses what’s called ProbSparse Attention. Rather than comparing every query with every key (which becomes computationally heavy as sequences grow), it selectively focuses on the most “important” queries—those with high information density. This drastically cuts down the number of computations while still preserving the key patterns in the data59. With its encoder-decoder structure and efficient attention layers, Informer is particularly good at handling long sequences and high-frequency data without compromising speed or performance. The key to Informer’s efficiency lays in its use of ProbSparse Attention (Eq. 1), which smartly focuses only on the most important queries—those with the highest relevance scores. By keeping just these top-k queries, it drastically cuts down the computation from the usual O(\({L}^{2}\)) to approximately O(LlogL), all while still capturing the important long-range patterns in the data.

Autoformer takes a more analytical approach to time-series forecasting. It breaks down input signals into two main parts: trend (the long-term direction) and seasonality (the repeating short-term patterns). This is done using a special block called SeriesDecompBlock. The seasonal part, which carries the rhythmic patterns, goes through the attention mechanism, while the trend is processed separately. This separation allows Autoformer to reduce noise and sharpen its focus on meaningful patterns. By doing this, it not only improves forecasting accuracy but also makes the model’s decisions more interpretable—especially useful in datasets where periodicity and trend shifts are central 60. Autoformer introduces a key advancement in time-series forecasting through a technique called series decomposition, expressed as:

In Eq. 17, \({x}_{t}\) is the original time-series at time step t. The trend component \({T}_{t}\) is extracted using a centered moving average with a window size of \(2k+1\), which smooths short-term fluctuations and emphasizes long-term patterns. The seasonal component \({S}_{t}\) is then obtained by subtracting the estimated trend from the original series, isolating the repeating cyclic behavior. This decomposition allows Autoformer to treat each component differently: the trend is modeled through a smoother pathway to capture gradual shifts, while the seasonal part is directed into the attention mechanism to better learn periodic dynamics. Ensemble Learning (FEDformer, Informer, and Autoformer) brings together their complementary strengths—capturing frequency patterns, handling long sequences efficiently, and modeling trends and seasonality—which boosts forecasting accuracy and robustness. However, this benefit comes at the cost of higher computational demands and reduced interpretability due to the added complexity of combining multiple models.

Performance metric to evaluate the time-series models

Evaluating models is crucial for assessing their accuracy and effectiveness. It allows us to analyze their performance, guide optimization efforts, and ensure reliability in decision-making processes61 MSE evaluates a model’s performance by calculating the average squared difference between the actual values \({y}_{i}\) and the predicted values \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) (Eq. 18). This metric is particularly useful for guiding optimization and improving model reliability.

The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is simply the square root of MSE. It provides an interpretable estimate of the average prediction error, expressed in the same units as the original data (Eq. 19):

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) captures the average magnitude of prediction errors without squaring them, making it less sensitive to outliers. Unlike MSE, it does not square the errors, making it less sensitive to outliers and offering a clear representation of the model’s average prediction error. (Eq. 20):

Finally, the Coefficient of Determination (R2) indicates the proportion of variance in the observed data that is explained by the model (Eq. 21):

Together, these metrics provide a balanced view of model performance—MSE, RMSE, and MAE quantify prediction errors, while R2 reflects the model’s explanatory power.

Hyperparameter tuning

The hyperparameter settings across all models were established through a systematic evaluation process, with final choices made after observing their performance during execution (Table 1). Core parameters, such as hidden dimensions, attention heads, and dropout rates, were tuned to maintain an effective balance between representational capacity, computational efficiency, and generalization. Model-specific components, including bottleneck structures, Fourier modes, and kernel sizes, were refined using a grid search strategy, allowing the models to adaptively capture feature representations and underlying patterns in the data. The search ranges for these parameters were defined based on insights from prior work, ensuring that the process remained both practical and grounded in established methods. Table 1 illustrates the selected configurations for each architecture, showing how multiple candidate options were explored within the defined ranges, with the final settings determined by validation outcomes. This process guarantees that the reported configurations are consistent, reproducible, and aligned with the study’s objectives.

Overall, the summarized configurations highlight the effectiveness of the selected hyperparameters in capturing data patterns while maintaining efficiency, providing a reliable foundation for the models used in this study.

Results and discussion

All experiments were carried out in a Python 3.6 environment using PyTorch 1.8.1 as the core deep learning framework. The implementation was run on a Windows 10 (64-bit) system equipped with an Intel i5 processor (3.4 GHz) and 8 GB of RAM. To ensure reproducibility of results, a fixed random seed (42) was applied, and model weights were initialized using the Xavier uniform strategy. The framework was further configured to automatically leverage a CUDA-enabled GPU when available, with computation defaulting to the CPU otherwise. This setup offered a reliable and consistent platform for model development and performance evaluation in predicting water quality parameters.

Preprocessing result using transformer

To prepare the dataset for forecasting BOD values with the Transformer model, a series of preprocessing steps were applied to ensure data quality and consistency. Missing entries were replaced with the corresponding column means, minimizing the risk of bias from incomplete records. All features were then standardized using StandardScaler so that they shared a uniform scale, supporting stable and effective model training. The dataset was partitioned into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing68. This balanced division allowed the model to learn from sufficient data, tune its parameters effectively, and demonstrate robust performance on unseen samples (Fig. 9).

(a) Visualization of attention head (post-softmax normalized values) in the TransGAN for generator and discriminator (b) correlation of generated data vs real data (c) TransGAN training loss and distribution matching metrics (d) KL distribution for feature wise (real data: blue, generated data: light coral, and orange indicate distributions are reasonably aligned.)

The TransGAN shows balanced attention (Fig. 9a): the generator keeps a stable, uniform focus with weights around 0.10–0.16, ensuring consistent synthesis, while the discriminator spans a wider range (0.01–0.14) with distinct peaks, highlighting its selective emphasis for better distinction. Together, this balance enhances adaptability and overall performance. The correlation matrices (Fig. 9b) indicate that the generated data effectively mirrors the relationships found in the real data, with most feature pairs exhibiting similar patterns and comparable correlation strengths. The generator gradually reduces its loss from around 5.5 to 4.5, reaching a stable state that indicates consistent learning. Meanwhile, the discriminator maintains a steady loss near 5.0–5.2, reflecting a balanced adversarial interplay. The distribution loss remains close to zero throughout, demonstrating the model’s effective alignment with the target data distribution. The TransGAN model demonstrates strong statistical fidelity (Fig. 9c), achieving a low Mean Absolute Error (0.0532) and Standard Deviation Error (0.0567), indicating the generated samples closely reflect the real WWTP data. Distributional metrics, including a Wasserstein Distance of 0.0939 and KS Statistic of 0.1138, further confirm the synthetic data aligns well with the real data. The KL Divergence of 1.4370, remaining under 1.5, shows reasonable distribution matching, though there is still room to refine the TransGAN architecture and training to reduce this divergence further, potentially enhancing the quality of synthetic WWTP data for downstream applications.

The Fig. 9d shows how the real (blue) and generated (pink) data distributions compare across 21 features, using KL divergence as a measure of similarity. Features like CODCO (0.222), PHCO (0.246), and CODUT (0.417) have very low KL values, indicating that the generated data closely follows the real distribution. Mid-range values, such as TSSN (1.678), Conductivity (1.587), and DOAR (1.566), suggest a reasonable overlap with some deviations. In contrast, higher KL values such as BODIN (2.913), PHAR (2.358), and BODOUT (2.956) highlight clearer differences between the two datasets. Overall, most features remain below a KL threshold of 3.0, suggesting that the generated data generally preserves the statistical behavior of the real dataset. Here, KL threshold 3 is set as a soft upper bound, with its suitability depending on the complexity and variability of the WWTP dataset 69.

The TransAuto model shows reliable and consistent performance in handling anomalies. Training loss steadily declines from 0.13 to 0.018, while validation loss reduces from 0.03 to nearly 0.002, reflecting strong generalization without signs of overfitting. The distribution of multi-head attention weights remains well balanced, with median values around 0.4–0.5, allowing the model to capture a wide range of anomaly patterns. Training MSE drops from 0.27 to 0.04 and validation MSE from 0.08 to about 0.005, confirming effective reconstruction capabilities Fig. 10a).

Among attention heads, Head 1 makes the largest contribution at 41.6%, followed by Head 7 (15.9%) and Head 6 (12%), while smaller shares from others such as Head 5 (2.0%) and Head 8 (3.9%) demonstrate complementary yet important roles in anomaly detection. The t-SNE visualization shows that, before correction, anomalies (red points) were dispersed and often overlapped with normal data, making them difficult to distinguish. After correction, these anomalies (green points) became much clearer and better separated, leading to the detection of 150 anomalies in total. Despite this improvement, the method still faces certain limitations—its performance can be highly sensitive to data normalization, it struggles with anomalies in skewed distributions, and there is a risk of overfitting when autoencoders are trained solely on normal data. (Fig. 10b).

The reconstruction error analysis provides further evidence: at first, the errors were spread widely with relatively high values, but after correction, they dropped significantly and consistently remained well below the 0.3 threshold. On the quantitative side, the model reached a precision of 0.7533, effectively minimizing false positives, while a recall of 0.5136 indicates that nearly half of the anomalies were successfully detected. The F1-score of 0.6108 shows a balanced trade-off between precision and recall, and the high accuracy of 0.9512 combined with an excellent ROC AUC of 0.9853 underscores TransAuto’s robust ability to distinguish normal patterns from anomalous ones (Fig. 10c).

The transformer model highlighted features such as BODCO, PHAR, CODCO, and TSSUFI, though their importance values were relatively small (~ 0.0001–0.0003), suggesting that predictions were driven by a balanced contribution across variables rather than a single dominant input (Fig. 11a). In contrast, the autoencoder assigned much higher normalized scores (0.49–1.00) to features like CODIN, PHUFI, TurbidityUFI, CODUFI, and PHIN, indicating a clearer hierarchy of influence (Fig. 11b). To ensure comparability, the outputs of both methods were normalized and merged into a unified ranking. From this ranking, PHAR (0.7257), CODCO (0.6403), and CODUFI (0.5891) emerged as the most critical, while TSSCO (0.1610) and BODOUT (0.0953) showed lower contributions (Fig. 11c). Top 12 features were selected (Fig. 11(d)) by applying threshold of 0.35, achieving strong predictive performance with an R2 of 0.9758 and an MSE of 0.025, which is close to the R2 of 0.9836 obtained with the full feature set (Fig. 11e). Empirical testing of feature selection showed a clear drop in performance, with the MSE increasing by more than 0.025. The average of multi-head attention scores and autoencoder reconstruction errors (Fig. 11f) further supports that integrating the two approaches yields a well-balanced and discriminative subset, with 12 features providing the most stable and reliable basis for downstream prediction.

Forecasting BOD value using transformer

To understand the effectiveness of using a Transformer model to forecast BOD values. The visualizations provide comprehensive insights: The training loss curve reflects how effectively the model has learned during training. Comparing predicted vs. actual values helps us gauge prediction accuracy. Time series and control charts highlight fluctuations and process stability over time. Monthly distribution charts point to seasonal patterns, while residual and error distribution plots reveal how the model handles deviations. The 15-day forecast provides a practical glimpse into upcoming BOD levels, and the seasonal trend decomposition uncovers long-term behavior in the data.

To help the model better understand how time influences BOD levels, the original date column was broken down into several meaningful features. These included the day, month, year, day of the week, and quarter—all of which offer insight into recurring patterns across weeks, months, and seasons. A day_of_year feature was also created to capture the position of each data point within the annual cycle, making it easier for the model to detect seasonal trends. Additionally, a binary is_weekend flag was added to indicate whether a given date falls on a weekend, which could reflect changes in human or industrial activity. By expanding the date into these time-aware components, the model gains a richer understanding of temporal behavior—ultimately improving its ability to make accurate predictions (Fig. 12).

The Encoder-Decoder Time Series Transformer demonstrates stable and accurate forecasting, as shown across multiple evaluation plots. Training converged smoothly, with both training and validation losses rapidly decreasing and stabilizing below 0.01 by the 50th epoch, indicating strong generalization without overfitting. The predicted versus actual scatter plot shows a tight alignment along the diagonal with only small deviations, confirming the model’s precision in reproducing BODOUT behavior. Across the full time series, predictions closely follow the historical range (0.0 to 1.0), while the control chart indicates almost all points remain within statistical limits (UCL ≈ 1.0, LCL ≈ 0.0, Mean ≈ 0.35), reinforcing the system’s stability. Monthly boxplots reveal distributions centered around 0.35, with little seasonal bias, while residuals scatter evenly around zero for both training and test sets, suggesting unbiased errors. The error distribution further validates this, with most errors concentrated tightly between –0.1 and 0.1, centered near zero. The 15-day forecast, however, shows a slight downward trend, with values decreasing from approximately 0.346 to 0.345, marginally below the mean of 0.35. Moving average plots (7-, 14-, and 30-day) smooth short-term fluctuations while preserving long-term patterns, and seasonal decomposition confirms a consistent repeating seasonal cycle oscillating around 0.35 (Fig. 13).

The TFT demonstrates strong and stable forecasting performance across all evaluation metrics. Training progressed efficiently, with both training and validation losses dropping sharply and leveling off below 0.01 by the 50th epoch, indicating effective learning and solid generalization. Predicted values closely follow actual observations along the diagonal, with only small deviations, reflecting high accuracy in modeling BODOUT behavior. Throughout the full time span, predictions remain well within the historical range of 0.0–1.0, while the control chart highlights system stability, with nearly all points falling between the UCL (~ 1.0) and LCL (~ 0.0) around a central mean of 0.46. Monthly distributions reinforce this consistency, as medians cluster near 0.46 without notable seasonal fluctuations. Residual plots show errors evenly centered around zero, and the error histogram further supports this, with the majority of errors concentrated in the narrow band of –0.1 to 0.1. The 15-day forecast projects a gentle upward movement, with values increasing slightly from 0.458 to 0.459, aligning with the overall mean prediction of 0.46. Smoothing through 7-, 14-, and 30-day moving averages effectively reduces noise while retaining the underlying trend, and seasonal decomposition confirms a repeating and stable seasonal cycle oscillating steadily around 0.46.

All three models—TST, TFT, and TimeGPT—show strong time-series forecasting performance, with consistently low errors and high \({R}^{2}\) values across training, validation, and test sets (Table 2). Among them, TST demonstrates the best overall balance, achieving the lowest test MSE (0.0028) and the highest \({R}^{2}(\) 0.9643), reflecting solid generalization capability. TFT performs closely, offering similar accuracy but with a lower test MAE (0.0347), which points to better handling of error magnitudes. TimeGPT also delivers reliable results, though its higher test MAE (0.0413) suggests slightly reduced precision compared to the other two. In summary, TST stands out for its consistency, TFT for minimizing deviations, and TimeGPT for stability, albeit with marginally less accuracy (Fig. 14).

The TimeGPT model shows strong stability and accuracy in forecasting, as evidenced by consistent results across multiple evaluation plots. Training progressed smoothly, with both training and validation losses dropping sharply and settling below 0.01 by the 50th epoch, indicating effective learning and good generalization. Predicted versus actual values align closely with the diagonal, with only minor deviations, demonstrating the model’s precision in capturing BODOUT dynamics. Over the full time series, predictions stay well within the historical range of 0.0–1.0, while the control chart highlights stability, with nearly all values falling between the UCL (~ 1.0), LCL (~ 0.0), and a mean near 0.55. Monthly boxplots further support this, with medians consistently centered around 0.55 and no noticeable seasonal drift. Residuals are evenly scattered around zero, and the error histogram confirms that most prediction errors fall tightly between –0.1 and 0.1, clustered near zero. Looking ahead, the 15-day forecast points to a slight downward trend, with predictions easing from 0.535 to 0.530, though remaining close to the mean of 0.54. Moving average plots over 7, 14, and 30 days effectively smooth out short-term noise while preserving the overall trend, and seasonal decomposition confirms a stable repeating pattern oscillating around 0.55 (Fig. 15).

The residual analysis of the outperformed TST model demonstrates its strong forecasting capability with well-structured and stable error behavior. Skewness values for training (0.159), validation (–0.130), and test (–0.098) remain close to zero, reflecting symmetric error distributions with little bias. Kurtosis values—1.996 for training, 2.658 for validation, and 2.035 for testing—are within acceptable bounds, indicating no excessive heavy-tailed effects and consistent variance control. Residual distributions and Q-Q plots show errors concentrated near zero with only minor tail deviations, while boxplots confirm that most residuals fall within narrow ranges with limited outliers. Together, these outcomes highlight that the TST maintains low-bias, well-balanced residuals and strong generalization, making it a reliable and robust choice for time-series forecasting.

Ensemble learning transformer model for forecasting

The forecasting results demonstrate stable and reliable performance across multiple evaluations. In the complete BODOUT time series, ensemble-based approaches remain well within the historical 0.0–1.0 range, with the stacking ensemble consistently centered around 0.35. When focusing on the 15-day horizon, the stacking ensemble continues to hold steady at approximately 0.35, while FEDformer (≈0.41), Autoformer (≈0.59), and Informer (≈0.60) display greater fluctuations. Trend analysis with 7-, 14-, and 30-day moving averages smooths short-term noise and converges toward 0.5, confirming long-term stability. Forecasts with 95% confidence intervals reinforce this reliability, as ensemble outputs remain close to 0.35 with bounded uncertainty between 0.3 and 0.4. On the test dataset, predictions from all models closely align with actual values, though stacking delivers the strongest fit. Residual diagnostics further support this finding, showing errors tightly distributed around zero and contained between –0.1 and 0.1, reflecting minimal bias and stable variance. The 15-day forecast generated by the stacking ensemble is almost flat, with values ranging only between 0.35 and 0.36, demonstrating robustness. Finally, the forecast table highlights this consistency, confirming that stacking surpasses FEDformer and Autoformer by generating smoother, more dependable predictions (Fig. 16a,b).

(a) Forecasting BOD value using Ensemble transformer learning models (b) performance of base and ensemble models (c) Model contribution (d) Seasonal components of Autoformer (e) Informer and FEDformer performance (f) The residual diagnostics (Skewness, Kurtosis and Q-Q Plot) for the outperformed Stacking Ensemble.

The results indicate that the FED Transformer makes the highest contribution at 33.84%, with the Autoformer contributing 33.21% and the Informer 32.95%. The differences are minimal, highlighting that all three models share nearly equal importance (Fig. 16c). This balanced distribution ensures the ensemble benefits from the strengths of each model, leading to more robust and reliable performance.

The Fig. 16d demonstrates how changing the kernel size affects time series decomposition in Autoformer transformer. With smaller kernels (size 5), the trend line captures quick fluctuations, while larger kernels (up to 35) smooth out the trend and reveal broader patterns. Similarly, the seasonal component becomes cleaner and more regular as kernel size increases, filtering out noise. This highlights how kernel size influences the patterns extracted. Unlike static filtering, ensemble Transformer models can learn both short- and long-term patterns automatically, making them powerful tools for time series analysis without the need to manually adjust kernel sizes.

The ProbSparse attention mechanism in Informer (Fig. 16e) selectively emphasizes key-query pairs with higher weights—up to 0.30—while suppressing less relevant interactions. This selective focus lowers computational cost and ensures that essential temporal dependencies are preserved, improving both efficiency and forecasting accuracy. The Fig. 16e further demonstrates how FEDformer’s Fourier Enhanced Blocks (FEB) function across two layers. In both Block 1 and Block 2, the frequency spectrum is sparse, dominated by a sharp peak at frequency 0 (magnitude ≈ 0.48). In Fourier analysis, this mode 0 (or frequency 0) represents the DC component, which captures the long-term mean or overall trend of the signal. The Fourier coefficients also concentrate at this mode, with a magnitude of around 0.10, reinforcing the prominence of low-frequency information. By isolating these dominant low-frequency patterns, FEB effectively captures the fundamental structures most relevant for long-horizon forecasting. The resulting 64-dimensional feature representations exhibit clear variability, reflecting temporal patterns with greater precision. Collectively, these results highlight FEDformer’s capacity to extract meaningful frequency-based features, which directly contributes to its strong performance in time series forecasting.

The outperformed stacking ensemble model (Fig. 16f) produces residual skewness values of 0.056 in training, 0.074 in validation, and 0.081 in testing. Since these values are close to zero, the residuals remain fairly symmetric and the errors are well balanced across all datasets. The corresponding kurtosis values—0.561 for training, 0.848 for validation, and 1.219 for testing—are all well below 3, indicating that the residual distributions are light-tailed with no evidence of heavy outliers. This is further confirmed by the Q-Q plots, where the points closely follow the theoretical diagonal line, showing only slight departures at the extreme ends. Together, these results suggest that the model’s residuals are stable, near-normal, and consistent across datasets, reflecting strong generalization capability (Table 3).

The comparison clearly shows how different models perform in time-series forecasting. Among the stand-alone architectures, FEDformer provides the strongest accuracy, achieving an MSE of 0.0037, RMSE of 0.0612, MAE of 0.0436, and R2 of 0.9529. Autoformer also performs well with an MSE of 0.0051 and R2 of 0.9351, while Informer trails behind with higher errors (MSE 0.0057, RMSE 0.0756). Ensemble learning improves results further, with the stacking ensemble—using Linear Regressor as the meta-learner—delivering the most reliable performance. It achieves the lowest error (MSE 0.0036, RMSE 0.0582, and MAE 0.0438) and the highest R2 of 0.9646, surpassing both individual models and other ensemble methods. Meanwhile, voting and weighted average ensembles yield moderate improvements, both reaching an MSE of 0.0044, RMSE around 0.0665 and R2 near 0.944. Overall, stacking with Linear Regressor emerges as the most effective strategy, combining predictive strength with stability.

State of art method comparison

Transformer-based models have set new standards in time series forecasting across a range of applications, their use in WWTP monitoring and prediction remains limited. In other domains, however, these models have shown impressive capabilities (Table 4).

Ting et al. enhanced urban energy forecasting using an improved TFT model, while Lihua et al. integrated physics-informed deep learning for wind speed prediction. Seunghyeon et al. applied TFT to model pressure in RO systems, outperforming LSTM. In wastewater treatment, Wafaa et al. introduced a 3D CNN–LSTM–Gaussian hybrid for accurate Total Phosphorus forecasting, and Xuan et al. combined graph attention, Informer, and AHP for spatiotemporal water quality analysis. However, pure Transformer architectures remain underutilized for multi-parameter prediction in WWTPs. Despite these advancements, a focused application of pure Transformer architectures for multi-variable forecasting in WWTP operations has yet to be fully realized. To fill this gap, a novel ensemble Transformer learning (ETL) approach has been introduced, merging the strengths of Informer, Autoformer, and FEDformer models. Applied to real-world WWTP datasets, the ETL framework delivers superior predictive performance, achieving an MSE of 0.0036, RMSE of 0.0582, MAE of 0.0438, and an R2 of 0.9646. These results highlight the model’s capability to accurately capture the complex temporal behaviors inherent in WWTP systems, establishing a new benchmark for data-driven forecasting in this critical environmental sector.

Conclusion

This research introduced a unified Transformer-based framework to advance wastewater quality forecasting, with four major contributions. To address data scarcity, TransGAN was developed to generate realistic synthetic samples, enriching both model training and dataset diversity. For anomaly detection and feature analysis, TransAuto, a Transformer Autoencoder, was proposed, enabling unsupervised identification of irregularities and extraction of influential features. On the predictive side, several advanced temporal models were examined, including TST, TFT with VSN and GLU, and pretrained TimeGPT. Among these, the Temporal Signal Transformer (TST) delivered the strongest results (MSE: 0.0028, RMSE: 0.0529, MAE: 0.0386, R2: 0.9643), outperforming both TFT (R2: 0.9610) and TimeGPT (R2: 0.9637). Ensemble learning further highlighted the value of Transformers, with Informer (R2: 0.9279), Autoformer (R2: 0.9351), and FEDformer (R2: 0.9529) showing solid performance, while stacking achieved the highest accuracy (R2: 0.9646).

The framework’s robustness was further validated through multiple experiments. TransGAN was assessed using KL divergence, confirming that the generated data preserved the statistical behavior of real samples. TransAuto achieved strong anomaly detection accuracy of 0.9512, and its feature selection capability was verified using an MLP model, which reached an R2 of 0.9758 with an MSE of 0.025. For forecasting validation, skewness values were close to zero and kurtosis values remained below three, indicating well-behaved prediction errors. These outcomes demonstrate that the framework not only achieves high accuracy but is also reliable and adaptable for real-time wastewater monitoring.

Overall, the results confirm that Transformer-based models are highly effective at capturing the complex nonlinear dynamics of wastewater treatment systems. This enables precise forecasting that supports timely interventions, better resource management, and contributes directly to sustainability goals such as SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). Looking ahead, future work should focus on real-world validation, edge AI deployment for on-site monitoring, and further refinement through hyperparameter tuning, advanced validation techniques, and SHAP-based feature engineering to enhance performance and interpretability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Secondary data in this work was derived from a Sewage Treatment Plant of a chemical industry. Measurements were done with a frequency of daily over a five-year interval and with uniform time spacing between the observations. One can further analyze or do further research by accessing the dataset.

References

Khondoker, M., Mandal, S., Gurav, R. & Hwang, S. Freshwater shortage, salinity increase, and global food production: a need for sustainable irrigation water desalination—a scoping review. Earth 4(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth4020012 (2023).

Bazaanah, P. & Mothapo, R. A. Sustainability of drinking water and sanitation delivery systems in rural communities of the Lepelle Nkumpi Local Municipality, South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 26, 14223–14255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03190-4 (2024).

Arora, N. K. & Mishra, I. Sustainable development goal 6: global water security. Environ. Sustain. 5, 271–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-022-00246-5 (2022).

Obaideen, K. et al. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus. 7, 100112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100112 (2022).

Sellappa, K. Sustainable transition to circular textile practices in Indian textile industries: a review. Clean. Techn. Environ. Policy https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-025-03193-x (2025).

Pundir, A. et al. Innovations in textile wastewater management: a review of zero liquid discharge technology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 12597–12616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-31827-y (2024).

Moretti, A., Ivan, H. L. & Skvaril, J. A review of the state-of-the-art wastewater quality characterization and measurement technologies Is the shift to real-time monitoring nowadays feasible. J. Water Process Eng. 60, 105061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105061 (2024).

Aparna, K. G., Swarnalatha, R. & Changmai, M. Optimizing wastewater treatment plant operational efficiency through integrating machine learning predictive models and advanced control strategies. Process Safety Environ. Protect. 188, 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.05.148 (2024).

Zong, Z. & Guan, Y. AI-driven intelligent data analytics and predictive analysis in industry 4.0: transforming knowledge, innovation, and efficiency. J. Knowl. Econ. 16, 864–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02001-z (2025).

Pang, H., Ben, Y., Cao, Y., Shen, Qu. & Chengzhi, Hu. Time series-based machine learning for forecasting multivariate water quality in full-scale drinking water treatment with various reagent dosages. Water Res. 268, 122777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.122777 (2025).

Sujatha, R. et al. Automatic emotion recognition using deep neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 84, 33633–33662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-20590-4 (2025).

Karami, P. et al. Design of a photonic crystal exclusive-OR gate using recurrent neural networks. Symmetry 16(7), 820. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym16070820 (2024).

Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Assessing the effectiveness of long short-term memory and artificial neural network in predicting daily ozone concentrations in Liaocheng City. Sci. Rep. 15, 6798. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91329-w (2025).

Mahadi, M. K. et al. Gated recurrent unit (GRU)-based deep learning method for spectrum estimation and inverse modeling in plasmonic devices. Appl. Phys. A 130, 784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-024-07956-z (2024).

Mienye, I. D., Swart, T. G. & Obaido, G. recurrent neural networks: a comprehensive review of architectures, variants, and applications. Information 15(9), 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15090517 (2024).

He, Y. et al. In-depth insights into the application of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in traffic prediction: a comprehensive review. Algorithms 17(9), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/a17090398 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. A novel local enhanced channel self-attention based on Transformer for industrial remaining useful life prediction. Eng. Appl. Artificial Intell. 141, 109815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109815 (2025).

Lastrucci, G., Theisen, M. F. & Schweidtmann, A. M. Physics-informed neural networks and time-series transformer for modeling of chemical reactors. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 53, 1570–7946. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-28824-1.50096-X (2024).

Cerrone, A. R. et al. Correcting physics-based global tide and storm water level forecasts with the temporal fusion transformer. Ocean Model 195, 102509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocemod.2025.102509 (2025).

Subbotin, B. S., Smirnov, P. I., Karelina, E. A., Solovyov, N. V. & Silakova, V. V. Comparative Analysis of TimeGPT, Time-LLM and MSET Models and Methods for Transport Telematics Systems of Signals Generating and Processing the Field of on Board Communications (Russian Federation, 2025).

Li, W. et al. Research progress in water quality prediction based on deep learning technology: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 26415–26431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-33058-7 (2024).

Li, Qi., Ren, X., Fei Zhang, Lu. & Gao, B. H. A novel ultra-short-term wind power forecasting method based on TCN and Informer models. Comput. Elec. Eng. 120, 109632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109632 (2024).

Yang, Y., Yuchao Gao, Hu., Zhou, J. W., Gao, S. & Wang, Y.-G. Multi-Granularity Autoformer for long-term deterministic and probabilistic power load forecasting. Neural Netw. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107493 (2025).

Yang, Z., Li, J., Wang, H. & Liu, C. An informer model for very short-term power load forecasting. Energies 18(5), 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18051150 (2025).

Hong, J.-T., Bai, Y.-L., Huang, Y.-T. & Chen, Z.-R. Hybrid carbon price forecasting using a deep augmented FEDformer model and multimodel optimization piecewise error correction. Expert Syst. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123325 (2024).

Lindemann, B., Müller, T., Vietz, H., Jazdi, N. & Weyrich, M. A survey on long short-term memory networks for time series prediction. Procedia CIRP. 99, 650–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2021.03.088 (2021).

Kang, H. Y. J., Ko, M. & Ryu, K. S. Tabular transformer generative adversarial network for heterogeneous distribution in healthcare. Sci. Rep. 15, 10254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93077-3 (2025).

Wang, A. X. & Nguyen, B. P. TTVAE: Transformer-based generative modeling for tabular data generation. Artificial Intell. 340, 104292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2025.104292 (2025).

Fallahian, M., Dorodchi, M. & Kreth, K. GAN-based tabular data generator for constructing synopsis in approximate query processing: challenges and solutions. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 6(1), 171–198. https://doi.org/10.3390/make6010010 (2024).

Sherlock, B. D. et al. The distance between: an algorithmic approach to comparing stochastic models to time-series data. Bull. Math. Biol. 86, 111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-024-01331-y (2024).

Creswell, A. & Bharath, A. A. Inverting the generator of a generative adversarial network. IEEE Transact. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 30(7), 1967–1974. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2875194 (2019).