Abstract

Electrical pudendal nerve stimulation (EPNS) has been proposed as a clinic-based option for post-prostatectomy incontinence (PPI), but comparative evidence is limited. We conducted a retrospective cohort study across three medical centers (2018–2022) comparing EPNS (24 sessions over eight weeks) with pelvic-floor muscle training plus transrectal electrical stimulation (PFMT + TES). Primary outcomes were changes from baseline to end of treatment in the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) score and 24-hr pad-test urine loss. The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7) score was assessed as a secondary outcome, and pad-free status was recorded at six months after treatment. In adjusted analyses using propensity-score overlap weighting of 389 men, EPNS was associated with larger improvements than PFMT + TES in ICIQ-UI SF (β − 4.34, 95% CI − 6.65 to − 2.02), 24-hr pad-test urine loss (β − 631.26 g, − 750.81 to − 511.70), and IIQ-7 (β − 2.86, − 5.14 to − 0.58). Unweighted within-group changes were directionally consistent. At the last follow-up, pad-free status was observed in 32.6% of men in the EPNS group versus 7.0% with PFMT + TES. These findings suggest that eight weeks of EPNS can reduce symptom burden and urine loss and yield patient-perceivable quality-of-life gains, although further studies are needed to evaluate the long-term effects.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT06130306 Registration Date 11/05/2023).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer, which is predominant in older males1, often necessitates radical prostatectomy (RP) to increase overall survival and cancer-specific survival in patients with localized lesions2. However, despite a wide range of reported incidence rates (2%-60%)3, urinary incontinence (UI) remains a major complication that significantly affects patient postoperative satisfaction4.

Postradical prostatectomy incontinence (PPI) is often attributed to a mix of detrusor abnormalities and sphincteric incompetence5. Despite existing evidence predominantly focusing on stress urinary incontinence (SUI), real-world observations highlight a spectrum of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) post-RP, including urge incontinence, urinary frequency, straining voiding, enuresis, etc6,7.

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) has shown efficacy in strengthening pelvic floor muscles (PFM) and increasing the external mechanical pressure on the urethra8. As a recommended component of conservative rehabilitation after RP, it is pragmatically combined with transrectal electrical stimulation (TES) to enhance peri-urethral striated muscle contraction9 and facilitate urinary continence recovery. The supporting evidence for TES as an adjunct is heterogeneous3,10,11, yet PFMT + TES was commonly implemented as an enhanced rehabilitation regimen across the participating centers during the study period.

Another physiotherapy of interest for PPI is electrical pudendal nerve stimulation (EPNS). Evidenced by a greater pelvic floor surface electromyogram amplitude12, EPNS promotes more efficient PFM contraction13. By engaging pudendal nerve pathways, it may influence continence mechanisms across mixed symptom profiles14,15,16,17.

Given that post-prostatectomy LUTS extend beyond SUI alone, evaluating therapeutic efficacy requires a broader perspective. Therefore, our aim was to compare EPNS with PFMT + TES under routine-care conditions in men with PPI. To reduce confounding in this observational setting, we applied a propensity score overlap weighting approach and framed inference for the overlap-weighted (OW) population. We hypothesized that EPNS would yield greater short-term improvements in continence-related symptoms and objective leakage than PFMT + TES, while maintaining acceptable safety.

Methods

Patient selection

This retrospective cohort study analyzed the medical records of patients with PPI from three medical centers between 2018 and 2022.

The study’s inclusion criteria stipulated that UI must be persisting ≥ 1 month following RP, with a minimum frequency of two episodes per week recorded in a 7-day bladder diary, and confirmation of residual cancer absence through pathological examination. Conversely, participants were excluded if: they presented high-risk pathological features including lymph node involvement, resection margin entanglement, or significant tumor size; preoperative incontinence was evident; continence-directed pharmacotherapy (including antimuscarinics and β3-agonists) had been administered; they were experiencing urinary tract infections, hematuria, postvoid residual volume exceeding 50 ml; postoperative serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration ≥ 0.2 ng/mL at the initial screening visit; neurological disorders; urethral stricture; the use of penile clamps, condom catheters, or any other conservative measures deemed unsuitable for incontinence evaluation by the investigators.

After standardized counseling describing the risks, potential benefits, and logistics of both options, the regimen was chosen jointly by the patient and treating clinician, reflecting patient preference and clinical context; both regimens were available at all centers during the study period, and the initiated regimen defined group membership.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Shanghai Pudong Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval No. pdzyy-2022-47, [Oct.2022]). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional policies. Given the retrospective design and use of de-identified data, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Treatment

Across participating centers, routine postoperative care included advising patients to perform home PFMT after catheter removal. After enrollment, protocol-specific instructions were applied to minimize cross-regimen contamination: patients allocated to EPNS were asked to suspend voluntary home PFMT/Kegel for the duration of EPNS, whereas the PFMT + TES regimen comprised supervised electromyogram-assisted PFMT followed by TES, with continuation of home PFMT as instructed.

All participating centers adhered to a single written protocol for both regimens, specifying unified equipment (same model), predefined parameter ranges, staff training with competency checklists, and an identical visit schedule (three sessions weekly for eight weeks). To minimize inter-operator variability, within each center all EPNS sessions were administered by the same designated acupuncturist and all PFMT + TES sessions by the same designated therapist. A site coordinator scheduled visits in advance and promptly rescheduled any missed sessions to support adherence and maintain intervention completeness.

In the EPNS group, patients were treated in the prone position. After skin antisepsis, four sacrococcygeal points were used for long-needle insertion. Needle placement was guided by palpation of bony landmarks (sacrococcygeal joint and coccygeal tip); no imaging guidance (e.g., ultrasound) was used. At the two upper points (~ 1 cm bilateral to the sacrococcygeal joint), a 0.40 × 100 mm needle was inserted perpendicularly to a depth of 80–90 mm to elicit a referred sensation to the anus. At the two lower points (~ 1 cm bilateral to the coccygeal tip), a 0.40 × 100/125 mm needle was inserted obliquely anterolaterally toward the ischiorectal fossa to a depth of 90–110 mm to elicit a referred sensation to the perineum (root of the penis). Two ipsilateral electrode pairs from an electrical stimulator (Shanghai Medical Instruments High-Techno, Shanghai, China) were connected to the needles (anode to the upper needle; cathode to the lower needle). The device delivered biphasic, charge-balanced pulses (pulse width 2 ms; frequency 2.5 Hz). Current intensity was titrated from a low starting level in small increments to the maximum tolerated without discomfort (typically 45–55 mA). Stimulation was titrated to achieve and maintain a visible cephalad pelvic-floor contraction (e.g., perineal lift and/or anal wink) accompanied by the patient-reported referred sensation throughout the 60-minute session. Safety was monitored continuously.

In the PFMT + TES group, after bladder voiding, patients were positioned supine (left-lateral as needed for comfort). A disinfected, lubricated transrectal probe was inserted per manufacturer instructions, and surface reference electrodes were placed over the anterior superior iliac spine and rectus abdominis as specified by the device program. Therapist-supervised electromyogram biofeedback–assisted PFMT was delivered using a nerve function reconstruction system (AM1000B; Shenzhen Creative Industry Co. Ltd, China) with the default pelvic-floor rehabilitation program (initial intermittent stimulation and template learning, followed by combined intermittent-stimulation biofeedback for type-I fibers, then biofeedback alone for type-I and type-II fibers). TES was then delivered using a neuromuscular stimulation system (PHENIX USB 4; Electronic Concept Lignon Innovation, France). Each visit comprised 20 min of electromyogram-assisted PFMT and 20 min of TES (total 40 min). During TES, current intensity was titrated from 0 mA upward in small increments to a comfortable pelvic-floor contraction (typically < 60 mA). Per the device program, stimulation alternated in 3-minute periods at 15 Hz and 85 Hz, with pulse width 200–300 µs; other program parameters followed manufacturer defaults (not user-adjustable). Patients were instructed in home PFMT (30 maximal contractions per session, holds 2–6 s with 2–6 s rest, three sessions daily for eight weeks).

Follow-up and outcome measurements

From cohort entry (baseline, T0), patients were followed for up to 6 months (T2) after the last session of treatment (T1). The primary effectiveness outcomes were changes in the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) score and the 24-hr pad test urine loss from T0 to T1. The ICIQ-UI SF is a robust questionnaire for assessing UI severity18, whereas the 24-hr pad test urine loss serves as a quantitative indicator of incontinence severity and treatment response19. The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7; on a 0–21 scale with reductions indicating improvement) score evaluates the adverse impact of UI on health-related quality of life (QOL)20, with changes in scores from T0 to T1 providing additional insight into treatment outcomes. In addition, the binary outcome—pad-free status (no pad use) was recorded at both T1 and T2 as a pragmatic proxy for absence of incontinence.

ICIQ-UI SF and IIQ-7 were interviewer-administered by trained staff using a standardized script, and the 24-hr pad test was patient-performed at home following a brief written instruction sheet.

Safety monitoring and adverse events

Adverse events were monitored during each supervised session by routine clinician inquiry and observation. Clinically significant events requiring medical evaluation, treatment modification, or session termination would have been documented. Minor, self-limiting sensations (e.g., transient perineal soreness during stimulation titration) were managed by adjusting intensity and were not systematically recorded.

Statistical analyses

R statistical software (version 4.2.3, The R Foundation) was used for all analyses, with a significance level of P < 0.05. For all samples, continuous variables are summarized as the means (SD); categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage for crude samples and proportions only for weighted samples.

In the primary analysis, to compare between-group differences, t-tests were used for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. A doubly robust estimation approach that integrated a propensity score-based OW procedure and outcome regression was used to address confounding variables. Based on prior research and authors consensus21,22, this study included 15 potential confounders (Table 1). Standardized mean differences (SMD) were calculated to compare baseline characteristics between crude cohorts, with covariates having an SMD greater than 10% adjusted via the OW approach to create balanced cohorts. Multiple linear regression models were employed for sensitivity analyses to confirm the primary outcome analysis results.

In secondary analyses, a multiple regression model was used to investigate influencing factors related to post treatment ongoing UI at different follow-up stages. Additionally, participants were categorized into various subgroups, and subsequent logistic regression analyses were then carried out with UI status (yes/no) as the dependent variable and the index intervention as the main independent variable, adjusting for baseline covariates; these analyses estimate associations and are not intended for causal inference.

To maximize information use and ensure robustness, we included all case data since prior literature for sample size calculation was lacking. To avoid bias from missing data, this study uses complete clinical data and full datasets.

Results

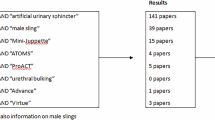

Among 596 patients with complete initial visit data for PPI, 389 patients (mean [SD] age, 68.80 [7.35] years) were analyzed (Figure 1). The distribution of 12 baseline covariates between the study groups was well- balanced after OW (Table 1); age, body mass index (BMI), and PSA showed residual imbalance, reflecting limited overlap mechanisms. Accordingly, inference is confined to the overlap-weighted population, with potential residual confounding acknowledged. Notably, among the patients in the OW analysis, the prevalence rates of mixed urinary incontinence (MUI), SUI, and urge urinary incontinence (UUI) were reported to be 49.6%, 48%, and 2.4%, respectively.

Clinical outcomes in patients

In the unweighted dataset, the EPNS group demonstrated a mean difference (SD) in the ICIQ-UI SF score of 9.26 (5.19), 24-hr pad test urine loss of 639.22 (383.99) g, and IIQ-7 score of 7.45 (5.27) following the final treatment. In contrast, the PFMT + TES group displayed a mean difference (SD) in the ICIQ-UI SF score of 2.43 (5.99), 24-hr pad test urine loss of 109.17 (331.60) g, and an IIQ-7 score of 2.99 (5.65). The OW analysis further confirmed these findings, revealing a significant reduction in ICIQ-UI SF scores (β=-4.34, 95% CI -6.65 to -2.02, P < 0.001), 24-hr pad test urine loss (β=-631.26, 95% CI -750.81 to -511.70, P < 0.001), and IIQ-7 scores (β=-2.86, 95% CI -5.14 to -0.58, P = 0.014) when EPNS was compared with PFMT + TES among the patients.

The sensitivity analysis utilizing three regression models (model 1 had no covariates adjusted, model 2 had some baseline covariates adjusted, and model 3 had all baseline covariates adjusted) emphasized the superiority of EPNS over PFMT + TES in reducing ICIQ-UI SF and IIQ-7 scores, and decreasing 24-hr pad test urine loss (Table 2).

Post-treatment UI occurrence and subgroup analysis

In the unweighted dataset, Pad-free status was observed in 19 EPNS and 14 PFMT + TES patients at the end of treatment, and in 29 EPNS and 7 PFMT + TES patients at the last follow-up.

In multiple logistic regression, PFMT + TES was associated with higher odds of post-treatment ongoing incontinence than EPNS— at T1 (OR 3.55, 95% CI 1.52–8.29; P = 0.003) and at T2 (OR 3.87, 95% CI 1.81–8.24; P < 0.001)—with similar magnitude and direction over time, supporting consistency of the primary finding. Among covariates, a sedentary lifestyle was associated with lower odds of post-treatment ongoing incontinence at both time points (T1: OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10–0.61; P = 0.002; T2: OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.23–0.89; P = 0.022); use of prostate cancer–directed systemic medication was associated with higher odds at T1 (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.08–5.52; P = 0.032); and higher pre-treatment IIQ-7 scores were associated with higher odds at T2 (OR 1.09 per point, 95% CI 1.01–1.18; P = 0.046).

Exploratory subgroup analyses indicated that within the MUI subgroup, therapy selection was associated with post-treatment ongoing incontinence: patients receiving PFMT + TES had higher odds of than those receiving EPNS (PFMT + TES vs. EPNS—T1: OR 9.50, 95% CI 1.35–66.76; P = 0.024; T2: OR 9.18, 95% CI 1.71–49.41; P = 0.010). By contrast, in the SUI subgroup there was no clear between-therapy difference (PFMT + TES vs. EPNS—T1: OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.11–16.32; P = 0.806; T2: OR 3.37, 95% CI 0.70–16.24; P = 0.130). Across other LUTS-defined strata (urinary frequency, postmicturition dribble, nocturia), no between-therapy differences were detected at either time point; estimates were imprecise with wide confidence intervals. For urgency urinary incontinence, straining, and enuresis, sample sizes were insufficient for reliable model-based comparisons, and no inferences are drawn. Exact estimates are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Association between the therapies selection and post-treatment urinary incontinence occurrence by the end of treatment. This figure displays the association between therapies and odds of post-treatment ongoing incontinence by the end of treatment, stratified by urinary incontinence type and postoperative lower urinary tract symptoms. EPNS, electrical pudendal nerve stimulation; PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training; TES, transrectal electrical stimulation; OR, odds ratio.

Association between the therapy selection and post-treatment urinary incontinence occurrence by six months after the final treatment. This figure reveals the association between therapies and odds of post-treatment ongoing incontinence by 6 months after the final treatment, stratified by urinary incontinence type and postoperative lower urinary tract symptoms. EPNS, electrical pudendal nerve stimulation; PFMT, pelvic floor muscle training; TES, transrectal electrical stimulation; OR, odds ratio.

Safety

No treatment discontinuations occurred due to adverse events, and no serious treatment-related complications were documented. Transient perineal soreness was occasionally noted during stimulation titration and resolved the same day after intensity adjustment; these mild reactions were not systematically captured.

Discussion

In the overlap-weighted population, EPNS was associated with greater improvements from T0 to T1 in ICIQ-UI SF score, IIQ-7 score and 24-hr pad test urine loss. The secondary analyses linked the EPNS to lower odds of post-treatment ongoing UI at different follow-up stages, indicating consistency of benefit over time.

PPI is multifactorial, involving intrinsic sphincter deficiency23 after removal of the proximal sphincteric contribution (bladder neck/prostatic urethra) and apical dissection24, alterations in urethral length and support22, and bladder dysfunction (e.g., detrusor overactivity or impaired compliance6. After RP, continence relies predominantly on the external urethral sphincter (rhabdosphincter)25 and pelvic-floor support (levator ani and fascial structures)26 under somatic and autonomic control; rehabilitation therefore focuses on restoring sphincter strength and coordinated pelvic-floor function27.

During the storage phase, rising intravesical pressure drives bladder afferents to Onuf’s nucleus, which in turn activates pudendal efferents to contract the rhabdosphincter. Concomitant levator ani contraction compresses the urethra and raises outlet resistance, sustaining the guarding reflex. This physiology explains the distinct modes of action in practice: PFMT (with or without TES) emphasizes motor re-education and strengthening of the pelvic floor, whereas pudendal-pathway stimulation can promptly recruit these reflex arcs to augment outlet closure and stabilize storage.

PFMT, which strengthens the pelvic diaphragm, is often combined with intracavitary electrical stimulation including TES to target sphincteric weakness10. Published data on TES after RP are limited and heterogeneous: small studies have used disparate stimulation parameters and outcome measures, and adjunctive TES with PFMT has shown variable short-term benefit across settings8,10,11. Conversely, EPNS is a clinician-delivered pudendal-pathway stimulation intended to elicit reproducible pelvic-floor and rhabdosphincter contractions via standardized electrode placement and titratable stimulation. This approach may mitigate the variability inherent to self-directed PFMT and may support adherence13. Nevertheless, the evidence base remains modest: clinical reports on EPNS are sparse; physiological studies demonstrate heightened pelvic-floor electromyogram activation with pudendal-pathway stimulation, and small clinical series suggest preliminary signals across mixed symptom profiles, including PPI [12]–17,28. In this context, our findings provide controlled, overlap-weighted comparative data consistent with greater clinical benefit of EPNS at treatment completion and at 6 months, while underscoring the need for confirmatory randomized trials.

Despite these therapeutic mechanisms, the likelihood of achieving full continence ultimately depends on the residual integrity of the rhabdosphincter and the levator ani/supporting fascia, together with their neurovascular supply29. Apical dissection can jeopardize these structures and thereby limit the ceiling of recovery. Consistent with this constraint, pad-free proportions were modest in our cohort: 32.6% in the EPNS group versus 7.0% in the PFMT + TES group at T2. Importantly, pad-free status should not be equated with complete continence as defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) (< 4 g/24-hr pad test)19, because some men elected not to use pads despite mild residual leakage. Regarding QOL, the between-group difference in IIQ-7 should be read as conservative: IIQ-7 is modestly responsive post-therapy, and its multi-domain aggregation can dilute group means when improvements occur unevenly across domains; moreover, QOL changes often lag behind symptomatic or objective gains as patients adapt behaviors and rebuild confidence. Although a firm minimal clinically important difference for IIQ-7 has not been established, the overall clinical picture—combining the ICIQ-UI SF improvement, the marked reduction in 24-hr pad test urine loss, and consistent advantages in pad-free status at different follow-up stages—indicates a modest but clinically relevant, patient-perceivable benefit that is directionally supportive of EPNS.

Aside from sphincteric complex incompetence, detrusor abnormalities can also shape post-prostatectomy symptoms. Chronic preoperative outlet obstruction may induce detrusor remodeling with reduced compliance or contractility30. Detrusor overactivity (DO) is frequently observed both before and after RP, contributing to storage-phase LUTS. Proposed mechanisms span neurogenic models (reduced inhibitory afferent control)8,31 and myogenic models (increased detrusor smooth-muscle excitability)32. RP may unmask pre-existing DO or promote it via partial autonomic denervation, leading to persistent or aggravated LUTS33. Importantly, DO identified after RP often pre-exists and co-occurs with sphincteric insufficiency30, yielding mixed symptom profiles rather than pure SUI.

In our crude cohort, 57.1% reported LUTS preoperatively, and storage-phase symptoms predominated postoperatively (urgency, 50.4%; frequency, 41.7%; enuresis, 23.1%; nocturia, 19.8%). This finding are broadly consistent with prior reports21, acknowledging variation across studies. We employed the OW method to balance symptom burden between groups, improving internal validity. Against this background, our post-treatment patterns suggest that beneficial signal with EPNS emerged in the MUI phenotype. In contrast, storage-phase symptom strata did not show a consistent differential effect across time points, and inference for voiding-phase symptoms was limited by small numbers.

EPNS offers a mechanistic rationale for addressing both storage and voiding dysfunction. EPNS can reinforce the guarding reflex and inhibit detrusor overactivity34, thereby stabilizing storage. Via the perineal branch, it may also facilitate the urethrovesical reflex to support more complete emptying35,36. However, only 5.6% of patients in the EPNS group and 17% of those in the PFMT + TES group manifested straining voiding, making it difficult to detect true efficacy differences in voiding phase LUTS. The comparatively stronger signal observed in MUI may reflect this dual action: when an urgency component is present, EPNS can reduce urge-related leakage while also supporting outlet function, yielding a larger net effect. By contrast, in pure SUI dominated by mechanical sphincter injury, the overall ceiling of recovery may constrain incremental gains despite neuromodulation.

This study has several limitations. First, the 6-month follow-up is short. It allows us to describe early post-treatment changes but cannot establish whether improvements persist, attenuate, or relapse thereafter; some background recovery may still occur within this window, and outcomes can also be shifted by post-baseline care changes (e.g., routine recovery trajectory, medication or lifestyle adjustments, oncologic management) that are not removed by baseline balancing. All analyses were restricted to the OW cohort with balanced baseline covariates, but overlap weighting does not address such after-baseline influences in a non-randomized study. Accordingly, these findings should be regarded as early estimates. Second, owing to patient status (24% experienced PSA recurrence during follow-up) and the use of phone-call visits, a comprehensive symptom reassessment at the last visit was not feasible for all participants; consequently, we recorded only the presence of ongoing urinary incontinence at T2. This binary endpoint carries less detail than continuous measures and can reduce precision/statistical power. Third, as this was not a randomized controlled trial, treatment selection reflected routine patient–clinician choice rather than randomization, residual confounding by indication may persist despite overlap weighting. Fourth, no study subject met the ICS continence standard, although some patients in both groups were pad-free. The procedure of pad test compromises its accuracy and reproducibility despite its widespread use37. Additionally, the limited sample size in certain subgroups constrained the capacity for subgroup analysis.

In conclusion, for the overlap-weighted population, EPNS was associated with greater short-term improvements in continence outcomes than PFMT + TES. Future research should focus on long-term efficacy and comparative effectiveness in diverse populations through prospective randomization to refine treatment guidelines for PPI.

Data availability

Deidentified participant data will be available upon publication. The requests should be sent to the corresponding author with a valid methodology. Only approved researchers with a signed data access agreement will have access to the data.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DO:

-

Detrusor overactivity

- EPNS:

-

Electrical pudendal nerve stimulation

- QOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IIQ-7:

-

Incontinence Impact Questionnaire-7

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- ICIQ-UI SF:

-

International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form

- ICS:

-

International Continence Society

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- MUI:

-

Mixed urinary incontinence

- OW:

-

Overlap weighted

- PFMT:

-

Pelvic floor muscle training

- PFM:

-

Pelvic floor muscles

- PPI:

-

Postradical prostatectomy incontinence

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- RP:

-

Radical prostatectomy

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean differences

- SUI:

-

Stress urinary incontinence

- TES:

-

Transrectal electrical stimulation

- UUI:

-

Urge urinary incontinence

- UI:

-

Urinary incontinence

References

Mottet, N. et al. EAU-eanm-estro-esur-siog guidelines on prostate cancer—2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur. Urol. 79, 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.042 (2021).

Bill-Axelson, A. et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 932–942. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1311593 (2014).

Kannan, P., Winser, S. J., Fung, B. & Cheing, G. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training alone and in combination with biofeedback, electrical stimulation, or both compared to control for urinary incontinence in men following prostatectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. 98, 932–945. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy101 (2018).

Abrams, P. et al. Outcomes of a noninferiority randomised controlled trial of surgery for men with urodynamic stress incontinence after prostate surgery (master). Eur. Urol. 79, 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2021.01.024 (2021).

Hoyland, K., Vasdev, N., Abrof, A. & Boustead, G. Post-radical prostatectomy incontinence: etiology and prevention. Rev. Urol. 16, 181–188 (2014).

Gacci, M. et al. Latest evidence on post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence. J. Clin. Med. 12, 1190. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031190 (2023).

Agarwal, A. et al. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur. Urol. 65, 1211–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.019 (2014).

Rahnama’i, M. S., Marcelissen, T., Geavlete, B., Tutolo, M. & Hüsch, T. Current management of post-radical prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Front. Surg. 8, 647656. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.647656 (2021).

Jabs, C. F. I. & Stanton, S. L. Urge incontinence and detrusor instability. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor. Dysfunct. 12, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001920170096 (2001).

Pané-Alemany, R. et al. Efficacy of transcutaneous perineal electrostimulation versus intracavitary anal electrostimulation in the treatment of urinary incontinence after a radical prostatectomy: randomized controlled trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 40, 1761–1769. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24740 (2021).

Benedetto, G. et al. The added value of devices to pelvic floor muscle training in radical post-prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review with metanalysis. PLOS ONE. 18, e0289636. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289636 (2023).

Feng, X., Lv, J., Li, M., Lv, T. & Wang, S. Short-term efficacy and mechanism of electrical pudendal nerve stimulation versus pelvic floor muscle training plus transanal electrical stimulation in treating post-radical prostatectomy urinary incontinence. Urology 160, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.069 (2022).

Wang, S. & Zhang, S. Simultaneous perineal ultrasound and vaginal pressure measurement prove the action of electrical pudendal nerve stimulation in treating female stress incontinence. BJU Int. 110, 1338–1343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11029.x (2012).

Wang, S., Lv, J., Feng, X. & Lv, T. Efficacy of electrical pudendal nerve stimulation versus transvaginal electrical stimulation in treating female idiopathic urgency urinary incontinence. J. Urol. 197, 1496–1501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.065 (2017).

Li, T., Feng, X., Lv, J., Cai, T. & Wang, S. Short-term clinical efficacy of electric pudendal nerve stimulation on neurogenic lower urinary tract disease: a pilot research. Urology 112, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.10.047 (2018).

Deng, K. et al. Daily bilateral pudendal nerve electrical stimulation improves recovery from stress urinary incontinence. Interface Focus. 9, 20190020. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2019.0020 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Bilateral electrical pudendal nerve stimulation as additional therapy for lower urinary tract dysfunction when stage II sacral neuromodulator fails: a case report. BMC Urol. 21, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-021-00808-5 (2021).

Avery, K. et al. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 23, 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20041 (2004).

Krhut, J. et al. Pad weight testing in the evaluation of urinary incontinence: pad weight testing. Neurourol. Urodyn. 33, 507–510. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22436 (2014).

Choi, E. P. H., Lam, C. L. K. & Chin, W. Y. The incontinence impact questionnaire-7 (IIQ-7) can be applicable to Chinese males and females with lower urinary tract symptoms. Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 7, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0062-3 (2014).

José, M. P. et al. Correlation between symptoms and urodynamic results in patients with urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Arch. Esp. Urol. 71, 523–530 (2018).

Heesakkers, J. et al. Pathophysiology and contributing factors in postprostatectomy incontinence: a review. Eur. Urol. 71, 936–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.09.031 (2017).

Castellan, P., Ferretti, S., Litterio, G., Marchioni, M. & Schips, L. Management of urinary incontinence following radical prostatectomy: challenges and solutions. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 19, 43–56. https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S283305 (2023).

Ficazzola, M. A. & Nitti, V. W. The etiology of post-radical prostatectomy incontinence and correlation of symptoms with urodynamic findings. J. Urol. 160, 1317–1320 (1998).

Strasser, H. et al. Transurethral ultrasound: evaluation of anatomy and function of the rhabdosphincter of the male urethra. J. Urol. 159, 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64025-4 (1998). discussion 104–105.

Kataoka, M. et al. Role of puboperinealis and rectourethralis muscles as a urethral support system to maintain urinary continence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Sci. Rep. 13, 14126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41083-8 (2023).

Kessler, T. M., Burkhard, F. C. & Studer, U. E. Nerve-sparing open radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 51, 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.013 (2007).

Wang, S., Zhang, S. & Zhao, L. Long-term efficacy of electrical pudendal nerve stimulation for urgency–frequency syndrome in women. Int. Urogynecol. J. 25, 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2223-7 (2014).

Song, C. et al. Relationship between the integrity of the pelvic floor muscles and early recovery of continence after radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 178, 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.044 (2007).

Porena, M., Mearini, E., Mearini, L., Vianello, A. & Giannantoni, A. Voiding dysfunction after radical retropubic prostatectomy: more than external urethral sphincter deficiency. Eur. Urol. 52, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.051 (2007).

Hennessey, D. B., Hoag, N. & Gani, J. Impact of bladder dysfunction in the management of post radical prostatectomy stress urinary incontinence—a review. Transl Androl. Urol. 6, S103. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2017.04.14 (2017). S10S111.

Peyronnet, B. et al. A comprehensive review of overactive bladder pathophysiology: on the way to tailored treatment. Eur. Urol. 75, 988–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.038 (2019).

Gomha, M. A. & Boone, T. B. Voiding patterns in patients with post-prostatectomy incontinence: urodynamic and demographic analysis. J. Urol. 169, 1766–1769. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000059700.21764.83 (2003).

Bosch, J. l. h. R. Electrical neuromodulatory therapy in female voiding dysfunction. BJU Int. 98, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06316.x (2006).

Elkelini, M. S., Abuzgaya, A. & Hassouna, M. M. Mechanisms of action of sacral neuromodulation. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1273-3 (2010).

Shafik, A., Shafik, A. A., El-Sibai, O. & Ahmed, I. Role of positive urethrovesical feedback in vesical evacuation. The concept of a second micturition reflex: The urethrovesical reflex. World J. Urol. 21, 167–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-003-0340-5 (2003).

Medeiros Araujo, C., De Morais, N. R., Sacomori, C. & De Sousa Dantas, D. Pad test for urinary incontinence diagnosis in adults: systematic review of diagnostic test accuracy. Neurourol. Urodyn. 41, 696–709. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24878 (2022).

Funding

The study is supported by Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Commission (The Young Medical Talents Training Program of Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Commission PWRq2022-47) and Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Commission (New Quality Clinical Specialty Program of High-end Medical Disciplinary Construction in Shanghai Pudong New Area2025-PWXZ-17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, SYW; Data curation, QC; Formal analysis, QC; Funding acquisition, TL and ZQH; Investigation, TL and TTL; Methodology, TL, TTL and SYW; Project administration, SYW; Resources, ZQH and SYW; Software, QC; Supervision, ZQH and SYW; Visualization, TTL; Writing – original draft, TL; Writing – review & editing, TL, TTL, ZQH and SYW.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local institutional review board (IRB) following the Helsinki Declaration (pdzyy-2022-47). The IRB waived informed consent because of the study’s nature.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, T., Wang, S., Chen, Q. et al. Electrical pudendal nerve stimulation versus pelvic floor muscle training with transrectal electrical stimulation for post-radical prostatectomy incontinence: a cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 41603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25567-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25567-3