Abstract

Bone tissue is generally resilient and can self-heal, but critical-size defects (CSDs) with complex geometries cannot be repaired without clinical intervention. Customized scaffolds developed using three-dimensional (3D) printing techniques can effectively repair complex-shaped CSDs. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), a type of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC), can differentiate into osteoblasts and exhibit osteoinductive properties. However, ADSC-single cells fabricated via two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures have limitations in maintaining cell survival and function over time. Unlike 2D monolayer cultures, ADSC-spheroids fabricated via 3D spheroid cultures can overcome this limitation by increasing the survival of ADSCs and enhancing their in vivo osteogenic capacity. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of a synergistic strategy of ADSC-spheroids within a 3D-printed scaffold made of polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite (PCL/HA) in bone regeneration. In vitro experiments demonstrated that ADSC-spheroids promoted mineralization in 3D-printed scaffolds. Radiographs and histological analysis performed at eight weeks post-implantation in in vivo experiments using a rabbit radial defect model showed successful bone regeneration in the group containing ADSC-spheroids within the PCL/HA scaffold. These results suggest that the synergistic strategy of incorporating ADSC-spheroids into 3D-printed PCL/HA scaffolds shows promise for clinical applications in treating complex CSDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone defects resulting from inflammation, trauma, tumors, or congenital anomalies present significant challenges to bone regeneration1. While bone tissue generally exhibits resilience and self-healing abilities, critical-size defects (CSDs) necessitate therapeutic intervention for proper repair2,3. Autologous bone grafts are considered the gold standard for treating these defects due to their favorable osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and cellular properties4. However, this approach has limitations including donor site morbidity, long surgical procedures, and limited availability5. Although alternative bone grafting materials such as allografts, xenografts, and alloplasts can address some of these issues, they have the disadvantage of reduced osteogenic capacity due to their lack of osteoinductive potential. Furthermore, these particle-type bone grafts are less likely to maintain their shape in CSDs, making it difficult to provide a structural framework for new bone formation6,7.

Stem cell-based therapies are emerging as promising solutions in bone tissue engineering (BTE) to enhance osteoinductive potential8. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells in various connective tissues throughout the body including the fetal liver, umbilical cord blood, adipose tissue, and adult bone marrow9,10,11,12. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), a type of MSC derived from adipose tissue, can differentiate into osteoblasts and exhibit osteoinductive properties13. Their osteoinductive potential is attributed to their high proliferation rates, low immunogenicity, and capacity to differentiate into multiple cell types9,14. In particular, ADSCs are considered highly suitable for clinical application due to their minimal donor site morbidity, abundance in adipose tissue, and ease of harvesting through minimally invasive procedures. Their robust proliferation, paracrine signaling ability, and immunomodulatory properties have been well-documented to enhance bone regeneration9,13,14. While some studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ADSCs in promoting bone regeneration, ADSC-single cells fabricated via two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures have limitations in maintaining cell survival and function over time15. These limitations may arise from the unphysiological microenvironment created by traditional 2D monolayer culture techniques16.

Recent advances in BTE have revealed the benefits of ADSC-spheroids fabricated via three-dimensional (3D) spheroid culture techniques17. This approach allows for direct cell-to-cell interactions, facilitating the formation of spheroids18. Unlike 2D monolayer cultures, 3D spheroid cultures better replicate the in vivo environment, enhancing cellular interactions, extracellular matrix (ECM) production, and overall tissue organization19. Moreover, the unique geometry of 3D spheroid cultures can induce anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and pro-angiogenic effects20,21,22. These characteristics enhance the osteoinductive potential of ADSCs in pathological bone repair, particularly in addressing challenges such as avascularity and hypoxia in large defects23. These improvements in ADSC-spheroid technology could significantly benefit the treatment of CSDs. Several studies24,25,26 have shown that spheroids of ADSCs effectively promote bone growth.

Scaffolds serve as 3D structures that provide a transient environment for cellular activity and ECM formation, enabling waste removal, nutrient delivery, and oxygen diffusion. These 3D structures also offer a structural framework to withstand external forces and gradually remodel as new bone tissue forms27. Customized 3D-printed scaffolds are crucial for regenerating CSDs with complex geometries28. Synthetic polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL), polylactic-glycolic acid (PLGA), and polylactic acid (PLA) are widely used materials for the 3D printing of scaffolds in BTE29. Among them, PCL is well suited for scaffold fabrication due to its thermoelastic behavior, mechanical strength, and controlled structural degradation time proportional to recovery. However, PCL has the disadvantages of low flexibility, lack of cell attachment sites, low performance, and the absence of functional groups on the polymer chain compared to natural bone tissue30,31,32.

Hydroxyapatite (HA) is a calcium phosphate with excellent biocompatibility, osteoconductivity, and cell adhesion and proliferation properties, making it very suitable as a bone substitute31,32. Numerous experiments have been conducted on biomedical scaffolds combining PCL and HA for BTE applications33,34. Jiao et al.33 and Kim et al.34 reported that 3D-printed PCL/HA scaffolds increased the mechanical strength of the scaffolds compared with PCL scaffolds alone. Therefore, a combination of PCL and HA can provide adequate mechanical strength to the scaffolds. The rationale for combining PCL and HA lies in their complementary properties: PCL provides favorable mechanical properties and tunable biodegradability, while HA improves osteoconductivity and cell affinity. This synergy is supported by several studies showing improved bone regeneration outcomes with PCL/HA composite scaffolds compared to either material alone33,34. Nevertheless, these 3D-printed polymer scaffolds typically have low osteoinductive capacity, which results in limited osteogenesis26,35. Current research is focused on increasing the osteoinductive potential of this 3D-printed scaffold to promote bone healing. One novel approach currently being investigated is the use of a synergistic strategy of incorporating MSC spheroids into 3D-printed scaffolds to improve the osteoinductive potential of the scaffold. By incorporating ADSC-spheroids into PCL/HA scaffolds, this strategy integrates the structural advantages of 3D printing with the biological superiority of spheroids, enabling better cell viability, matrix production, and functional bone regeneration.

Promoting bone regeneration in complex CSD is critical to effectively treating patients and reducing long-term healthcare costs. Despite the growing interest in the synergistic strategy of MSC spheroids and scaffolds, few studies have investigated this strategy in vivo for bone tissue regeneration36,37. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of ADSC-spheroids within a 3D-printed scaffold made of PCL and HA in repairing CSDs utilizing a rabbit radial defect model.

Results

Spheroid formation and cell viability

ADSC-spheroids were successfully established in silicone elastomer-based concave microwells after one day of culture (Fig. 1a). Cell viability was assessed using a fluorescence-based live/dead assay. Viable cells emit green fluorescence, while dead cells exhibit red fluorescence. On day 1, most ADSC-single cells and spheroids displayed green fluorescence, indicating high viability. While high viability was observed in the initial days of culture, an increase in red fluorescence indicating cell death became more apparent by day 7, particularly in the ADSC-single cell group compared to the ADSC-spheroid group (Fig. 1b).

Spheroid formation and cell viability of adipose-derived stem cells. (a) Spheroids of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSC) were successfully formed in silicone elastomer-based concave microwells after one day of culture. (b) The assay showed high initial viability. By day 7, an increase in dead cells (red) became more apparent, particularly in the ADSC-single cell group, suggesting a higher survival rate in the spheroid configuration over time.

Alizarin red S staining analysis

Alizarin Red S staining was conducted to assess the level of calcification after 7 and 14 days of osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 2a). The relative values of the Alizarin Red S-stained area at day 7 were 7.03 ± 1.41, 56.95 ± 0.72, and 69.23 ± 1.58% for the No cells, ADSC-single cell, and ADSC-spheroid groups, respectively, and on day 14, they were 6.0 ± 1.51, 86.86 ± 3.10, and 100.37 ± 2.10%, respectively (Fig. 2b). The Alizarin Red S-stained area in the ADSC-single cell and ADSC-spheroid groups was significantly higher than that in No cells group on days 7 and 14, with a significant increase on day 14 compared with day 7. On days 7 and 14, the ADSC-spheroid group had the most Alizarin Red S staining among the groups.

In vitro evaluation of 3D-printed scaffolds with single cells and spheroids of adipose-derived stem cells. (a) Alizarin red S-stained images showing calcium deposition. (b) Graph of the Alizarin Red S staining assay. (c) Graph of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay. ADSC: Adipose-derived stem cell; No cells group: 3D-printed scaffold; ADSC-single cell group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-single cells; ADSC-spheroid group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-spheroids. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated as †p < 0.05, ††p < 0.01 vs. No cells group, ##p < 0.01 vs. ADSC-single cell group, and *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. Day 7.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity analysis

ALP activity was measured after 7 and 14 days of osteoblast differentiation. At day 7, the ALP activity was found to be 33.37 ± 0.25 ng/ml for the ADSC-single cell group and 45.0 ± 0.61 ng/ml for the ADSC-spheroid group. By day 14, the values were 43.07 ± 2.54 ng/ml for the ADSC-single cell group and 70.38 ± 0.48 ng/ml for the ADSC-spheroid group. The ALP activity was significantly increased on day 14 compared with day 7 in both the ADSC-single cell and ADSC-spheroid groups. On day 14, the ADSC-spheroid group showed significantly higher ALP activity than the ADSC-single cell group (Fig. 2c).

Radiographic analysis

Both plain radiographs and micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) images showed that the 3D-printed scaffolds were well-maintained within the defect area until eight weeks post-implantation in all experimental groups. New bone formation started from the margins of the defect (Fig. 3a). Quantitative analysis using micro-CT showed that the new bone volume (NBV, mm3) of the Control, No cells, ADSC-single cell, and ADSC-spheroid groups were 57.83 ± 8.33 mm3, 83.83 ± 10.23 mm3, 87.35 ± 9.55 mm3, and 110.19 ± 12.13 mm3, respectively, on day 7. On day 14, the NBVs of the Control, No cells, ADSC-single cell, and ADSC-spheroid groups were 94.08 ± 6.65 mm3, 112.84 ± 12.43 mm3, 117.82 ± 11.04 mm3, and 145.58 ± 6.48 mm3, respectively. This micro-CT analysis showed a tendency for more new bone formation in the ADSC-spheroid group than in the No cells and ADSC-single cell groups at weeks 4 and 8; however, this difference was not significant. The ADSC-spheroid group showed significantly more new bone formation than the Control group (Fig. 3b).

Radiographic analysis of rabbit radial defects. (a) Plain radiographs, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) images, and 3D images of the rabbit radial defects eight weeks post-implantation. (b) Micro-CT quantification of new bone volume (mm3) at 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation. ADSC: Adipose-derived stem cell; Control group: only critical-size defect; No cells group: 3D-printed scaffold; ADSC-single cell group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-single cells; ADSC-spheroid group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-spheroids. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 5). Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05 vs. Control group.

Histological analysis

Histological examination indicated no adverse reactions, such as inflammation, at the scaffold implantation site for any experimental group at 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation. At 4 weeks post-implantation, minor bone regeneration was observed at the defect margin in all groups. At 8 weeks post-implantation, bone regeneration was confirmed at the defect margin in the Control group. In the other experimental groups, new bone formation was evident at the margins and center of the defect site (Fig. 4). The percentage of NBV was analyzed by quantitatively measuring the stained area of new bone within the defect using an ImageJ-converted image. At week 4, the percentage NBV was calculated to be 4.47 ± 0.63%, 7.55 ± 1.08%, 8.73 ± 1.01%, and 10.8 ± 0.48% for the Control, No cells, ADSC-single cell, and ADSC-spheroid groups, respectively. At week 8, the Control, No cells, ADSC-single cell, and ADSC-spheroid groups showed percentage NBVs of 9.76 ± 1.41%, 13.44 ± 0.89%, 14.62 ± 1.46%, and 16.33 ± 0.85%, respectively. This analysis showed a tendency for more new bone formation in the ADSC-spheroid group than in the No cells and ADSC-single cell groups at weeks 4 and 8; however, this difference was not significant. The ADSC-spheroid group showed significantly more new bone formation than the Control group (Fig. 5).

Histological images of rabbit radial defects. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained images 8 weeks post-implantation. (b) Masson’s trichrome (MT)-stained images 8 weeks post-implantation. ADSC adipose-derived stem cell; Control group: only critical-size defect; No cells group: 3D-printed scaffold; ADSC-single cell group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-single cells; ADSC-spheroid group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-spheroids; Arrows: defect margin; nb: new bone; ob: old bone; ct: connective tissue.

Histological analysis results of rabbit radial defects. (a) Masson’s trichrome (MT)-stained images and ImageJ-converted images of rabbit radial defects at 8 weeks post-implantation. (b) ImageJ analysis quantification of the percentage of new bone volume (%) at 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation. ADSC: Adipose-derived stem cell; Control group: only critical-size defect; No cells group: 3D-printed scaffold; ADSC-single cell group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-single cells; ADSC-spheroid group: 3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-spheroids; Arrows: defect margin. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 5). Statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. Control group.

Discussion

Stem cell-based therapies are emerging as promising solutions to treat bone defects due to the capacity of MSCs to differentiate into multiple cell types including osteoblasts8. MSC culture techniques are crucial for effectively expressing the osteoinductive properties of MSCs. Traditional 2D monolayer culture techniques cannot create a physiologically suitable 3D microenvironment for MSC differentiation16. Three-dimensional spheroid culture techniques attract attention in tissue engineering because they promote cell-to-cell interactions to form spheroids, facilitating excellent cell differentiation18. Recent studies have shown that the expression of cytokines, such as fibroblast growth factor 2, angiogenin, angiopoietin 2, hepatocyte growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factors, is also significantly increased in MSC spheroids, which provides a 3D microenvironment that is favorable for the differentiation of MSCs in the body38,39,40. A spheroid formed by the aggregation of MSCs can improve the therapeutic potential of MSCs for the regeneration and repair of bone defects.

Considering the abovementioned advantages of MSC spheroids, it was expected that superior osteogenic differentiation would be observed in vitro in ADSC-spheroids over ADSC-single cells. To evaluate early and mid-stage cell viability on the scaffolds, Live/Dead assays were conducted at days 0, 1, 4, and 741,42,43. Our Live/Dead assays indicated that while cell viability was high initially, some cell death occurred over the 7-day culture period. This could be attributed to limitations in nutrient and oxygen diffusion within the 3D scaffold environment. However, the ADSC-spheroid group consistently showed a lower proportion of dead cells compared to the single-cell group, suggesting that the spheroid structure offers a protective effect, enhancing cell survival in vitro. Although longer-term viability (e.g., day 14) was not assessed due to technical limitations, future studies will aim to include extended viability analyses to better elucidate long-term cell survival and function.

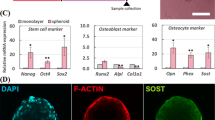

ALP activity, a well-studied early marker of osteogenic differentiation, was utilized to study the osteogenic differentiation capacity of spheroids44,45. In addition, Alizarin Red S staining was used as an indicator of osteogenic maturation of ADSCs to visualize and quantify the presence of a calcified matrix in the cell46,47. This study showed that ADSC-spheroids exhibited relatively more osteogenic activity than ADSC-single cells when measured by ALP activity and Alizarin Red S levels (Fig. 5). This result is thought to be related to accelerated osteogenesis and mineralization due to increased cell-cell contact and bone-specific ECM secretion in spheroids48. Overall, the results of this study are in accordance with those of other studies demonstrating osteogenic differentiation of MSC spheroids. For instance, Li et al.49 compared the ALP activity between single cells and spheroids of alveolar bone-derived MSCs (AB-MSCs). They reported that the AB-MSC-spheroids had significantly higher ALP activity than the AB-MSC-single cells after 14 days of culture. Shanbhag et al.36 compared the level of mineralization of single cells and spheroids of bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) using an in vitro Alizarin Red S staining assay. They reported that a higher mineralization tendency was observed in BMSC-spheroids than in BMSC-single cells after 21 days of culture. Similar results were also observed in a study using human ADSCs (hADSCs) conducted by Gurumurthy et al.50.

However, transplanting stem cell spheroids into bone defects in vivo remains challenging. The most effective spheroid delivery method to the regeneration site has not been thoroughly studied. Traditional in vivo administration of spheroids involves seeding cells directly onto a scaffold before implantation. However, this direct seeding method makes it difficult to evenly distribute cells on the scaffold and maintain their function51. Several recent studies52,53,54 have demonstrated superior cell function and osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo by encapsulating MSC spheroids in hydrogels. Unlike direct seeding, encapsulating spheroids in hydrogels maintains cell function during in vivo implantation. In this study, collagen gel was used as a hydrogel carrier to encapsulate ADSC-spheroids and facilitate their delivery into bone defects. Collagen offers excellent biocompatibility and ECM-mimetic properties that support cell adhesion, viability, and osteogenic differentiation. Notably, Kang et al. (2013) demonstrated that the incorporation of type I collagen gel within a porous scaffold significantly enhanced the homogeneous distribution and osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, which was evidenced by enhanced ALP activity and matrix mineralization55.

Three-dimensional printing technology offers an excellent opportunity to create customized 3D-printed scaffolds for treating complex bone defects. A primary advantage of 3D printing is the capacity to fabricate scaffolds with complex porous structures. Porous scaffold networks with interconnected structures help cell migration, growth, and promotion56. Increasing pore size enhances osteogenesis by facilitating vascularization; nevertheless, it concurrently diminishes the structural mechanical integrity33,57,58. Some studies have reported that implants with pore sizes larger than 300 μm have better cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, nutrient delivery, and osteogenesis33,57,59. Wang et al. applied a scaffold with a pore size of 200–500 μm to femoral shaft defects in dogs and found it to be osteoinductive with good biocompatibility60. A customized 3D-printed scaffold is essential for the attachment and proliferation of anchorage-dependent osteoblasts. If the scaffold and host bone meet tightly without gaps, new bone formation can be promoted outward from the host bone61. In this respect, customized 3D-printed scaffolds with complex geometries are crucial for filling and repairing complex CSDs. To evaluate the potential of bone regeneration in vivo, customized 20-mm long 3D-printed scaffolds were fabricated with a pore size of 500 μm.

In this study, we selected 20 wt% hydroxyapatite (HA) as the scaffold composition based on previous studies showing that this ratio provides a practical balance between mechanical strength, printability, and osteoconductivity. Jiao et al. reported that 20% HA improved tensile and flexural strength compared to pure PCL, while Kim et al. and Bilgili et al. demonstrated that this ratio maintained favorable mechanical properties and supported bone tissue formation33,34,62. While scaffold fabrication in this study was guided by these prior findings to ensure appropriate printability and mechanical performance, future studies would benefit from including material characterization, as well as an evaluation of HA distribution within the printed scaffolds and its behavior during in vitro culture, to further validate the structural and functional properties of the scaffold.

The efficacy of the scaffolds containing ADSC-single cells or spheroids was assessed using a 20-mm long radial defect model in rabbits. The scaffolds matched the defect area well and were firmly connected to the host bone without gaps. In the radiographic analysis, the 3D-printed scaffolds were securely positioned in the defect, and new bone formation occurred over the scaffolds from the defect margin at weeks 4 and 8 post-implantation. Quantitative analysis using micro-CT showed a non-significant tendency for increased new bone formation in the ADSC-spheroid group compared with the No cells and ADSC-single cell groups at weeks 4 and 8. Only the ADSC-spheroid group showed significantly greater new bone formation than the Control group. Histological analysis did not reveal any specific inflammatory responses in any group, and the results of new bone formation between the groups were similar to the micro-CT analysis results. These findings suggest that the superior osteogenic potential of ADSC-spheroids may be attributed to their enhanced in situ mineralization. Previous studies have reported that MSC spheroids promote bone regeneration through increased cell–cell interactions and enhanced paracrine signaling38,39,40. The 3D architecture of spheroids also preserves cell viability during implantation and replicates the native stem cell niche, enabling more effective osteogenic differentiation compared to dissociated single-cell suspensions. Although the enhanced bone formation observed in this study is likely attributed to the previously discussed properties of ADSC-spheroids, future research would benefit from incorporating additional osteogenic markers—such as osteocalcin or collagen type I—and performing mechanistic evaluations of spheroid behavior. These analyses would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the regenerative role of ADSC-spheroids.

Few studies have explored the synergistic strategy of applying MSC spheroids with 3D-printed scaffolds to bone defects36,37. Kronemberger et al.37 evaluated the osteogenic effect of the synergistic strategy using 3D-printed scaffolds with manually seeded hADSC-spheroids in a rat calvarial defect model. The researchers found that hADSC-spheroids in 3D-printed scaffolds successfully promoted new bone formation; however, the new bone formation was not significantly greater than that achieved without hADSC-spheroids in the scaffold. Shanbhag et al.36 evaluated the osteogenic effect of a synergistic strategy using 3D-printed scaffolds with hydrogels containing either hBMSC-single cells or spheroids in a rat calvarial defect model. Despite a trend for superior in vitro mineralization of hBMSC-spheroids, scaffolds containing hBMSC-single cells or spheroids showed similar osteogenic performance in vivo. In the present study, the 3D-printed scaffolds with collagen hydrogels containing cells were applied to a rabbit radial defect model. The results showed significantly more new bone formation in the ADSC-spheroid group than in the Control group, suggesting that this strategy has the potential for regeneration of complex bone defects. Considering that the ADSC-spheroid group did not show significant differences from the other groups except for the Control group, further studies will need to adjust the number of experimental animals and the delivery method of spheroids in vivo.

It should be noted that the scaffold showed no signs of degradation or replacement during the 8-week experimental period. PCL is widely used in tissue engineering due to its biocompatibility and mechanical strength; however, it degrades slowly over a period of 2 to 3 years63. Although new bone formation was observed around the scaffold, the structure itself remained largely intact, and no scaffold replacement by bone was evident. The prolonged presence of undegraded PCL may provide mechanical stability in the early phase of healing, but it could also interfere with long-term bone remodeling or delay full integration with host tissue. Moreover, the in vivo degradation behavior of PCL/HA composites may depend on the HA content, yet this relationship remains poorly understood. Since this study did not assess scaffold degradation due to the limited experimental period, further studies should include long-term implantation models and mechanical testing to evaluate how degradation kinetics relate to structural stability and biological remodeling in critical-sized bone defects.

While previous studies have explored PCL/HA scaffolds for bone regeneration, our study contributes to the field by specifically evaluating a synergistic strategy that combines ADSC-spheroids with 3D-printed PCL/HA scaffolds within a clinically relevant, critical-sized rabbit radial defect model.The findings revealed that this approach enhanced the osteogenic differentiation of ADSC-spheroids in vitro and promoted more effective osteogenesis in vivo, with significantly greater new bone formation observed in the ADSC-spheroid group compared to the Control group.

Nonetheless, we acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, a comprehensive characterization of the fabricated scaffolds—including their mechanical stiffness, degradation kinetics, and the stability of HA particles during culture—was not performed. Our fabrication was based on established literature to ensure feasibility, but future studies should include these essential material characterizations to fully validate the scaffold’s structural and functional properties. Second, SEM analysis to directly visualize cell-scaffold interactions was not conducted, which would have provided valuable morphological evidence. Finally, while our findings demonstrate significant bone formation, the study would be strengthened by incorporating molecular analyses of specific osteogenic markers, such as Collagen Type I or Osteocalcin, to provide deeper mechanistic insights. These limitations highlight important avenues for future research to build upon our findings.

Future research should optimize spheroid delivery methods to 3D-printed scaffolds, potentially incorporating advanced techniques such as 3D bioprinting to enhance regenerative outcomes. Furthermore, comprehensive studies—including long-term degradation analysis, material characterization, and molecular or immunohistochemical evaluation—are needed to fully assess the therapeutic potential of this strategy. If these aspects are validated in future work, the use of ADSC-spheroids with 3D-printed scaffolds may offer a promising clinical solution for treating complex critical-sized bone defects.

Methods

Fabrication of 3D-printed scaffold

Three-dimensional-printed scaffolds were fabricated using PCL (molecular weight = 80,000; Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) and HA powder (< 200 nm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A composite blend was prepared by mixing 20 wt% HA powder with molten PCL at 120 °C under continuous stirring for 1 h to ensure homogeneous dispersion, following a previously reported method64. The resulting PCL/HA mixture was loaded into a stainless-steel syringe and extruded using a pneumatic 3D plotting system (T&R Biofab Co., Ltd, Siheung, Republic of Korea) through a steel nozzle with an inner diameter of 300 μm. The printing temperature was set to 100 °C, and pneumatic pressure was maintained at approximately 600 kPa. For in vitro experiments, scaffolds were fabricated with a diameter of 7.8 mm and a height of 1.2 mm. The printing pattern was a 0°/90° lay-down with a line width of 300 μm and pore size of 500 μm (Fig. 6). The scaffolds were sterilized by immersion in 70% ethanol for 3 h in a 24-well cell culture plate (Falcon® Cell Culture Plate, #353047, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), followed by overnight drying under UV light on a clean bench. For in vivo experiments, scaffolds measuring 4 mm in diameter and 20 mm in length were fabricated using the same method to fit the rabbit radial defect model (Fig. 7).

3D-printed scaffold fabrication for in vivo experiments. (a) Design specifications of the 3D-printed scaffold, featuring a length of 20 mm and a diameter of 4 mm. The schematic drawing was created by the authors using SolidWorks (Dassault Systèmes, SolidWorks 2023, https://www.solidworks.com/). (b,c) Side and orthogonal views of the scaffolds designed for in vivo experiments.

Cell isolation and 2D monolayer culture

ADSCs were obtained from three-month-old male New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits (weight: 3.0–3.5 kg, Damool Science, Daejeon, Republic of Korea), following procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University in Korea (Approval No. CNU IACUC-YB-2022-149). The adipose tissue harvested from the interscapular area of the rabbits was extensively washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, #14190-144, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The tissue was chopped and digested for 1 h at 37 °C in a shaking water bath using 2 mg/ml collagenase type I (#LS004196, Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Worthington, NJ, USA) in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, #14025-092, Gibco Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA). The digested mixture was filtered through a 100-µm cell strainer (Corning® 100 μm cell strainer, #CLS431752, Corning Inc.) and centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 10 min. The pelleted cells were resuspended in HBSS, followed by a second centrifugation. The ADSCs were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12, #11320033, Gibco Inc.) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #16000-044, Gibco Inc.) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin, #15140-122, Gibco Inc.) at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were passaged using 0.25% trypsin with EDTA (#SH30042.02, Thermo Scientific Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), and the media was changed every two days.

3D spheroid culture

ADSC-spheroids were formed using a commercially available silicone elastomer-based concave microwell array (StemFIT 3D, #H853400, MicroFIT, Seongnam, Republic of Korea) containing hemispherical wells with a diameter of 400 μm. Although the exact depth of the wells is not specified in the manufacturer’s documentation, the wells are designed for high-throughput, uniform spheroid formation with a recommended culture medium volume of 1 mL per plate. A total of 1.2 × 10⁶ cells were suspended in 1 mL of medium and loaded into each well plate, resulting in a cell density of 1.2 × 10⁶ cells/mL. Cells were cultured in alpha modification of minimal essential medium (α-MEM, #A10490-01, Gibco Inc.) supplemented with 15% FBS and 1% antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin). Spheroids were harvested by gently pipetting with a wide-bore pipette tip without enzymatic treatment, following the manufacturer’s standard protocol. The formation and morphological changes of the ADSC spheroids were observed using an inverted phase-contrast fluorescence microscope (Leica DM IL LED Fluo, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Cell seeding and differentiation on PCL/HA scaffolds

The 5 mg/ml collagen gel was prepared by dissolving porcine-derived collagen (MoreBio Co., Ltd., Hanam, Republic of Korea) in acetic acid (Duksan Pure Chemical Co., Ansan, Republic of Korea) for 8 h. The solution was then chemically cross-linked using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) (both Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by dialysis against distilled water for 24 h65. ADSCs, either as single cells or spheroids, were suspended at 1.2 × 10⁶ cells/mL in 0.1 mL of crosslinked collagen gel. The cell-laden collagen was injected directly into the 3D-printed scaffold and allowed to gel at 37 °C for 30 min to promote cell retention. The scaffolds were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid (#A92902, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 5 mM β-glycerophosphate (#G9422, Sigma-Aldrich), 15% FBS, and 1% antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin) at 37℃. The osteogenic differentiation medium was replaced every two days during the differentiation period. The structure was visually intact throughout handling and implantation.

Cell viability test

The viability of ADSC-single cells and spheroids on the scaffolds was analyzed using a Live/Dead assay kit (#L3224, Invitrogen®, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at days 0, 1, 4, and 7. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate (n = 3). The ADSC-single cells and spheroids were stained in 1 ml of DMEM/F-12 containing 0.5 µl of calcein acetomethyl ester (4 mM; Invitrogen®) and 2 µl of ethidium homodimer-1 (2 mM; Invitrogen®) for 30 min at room temperature. After 30 min, the samples were examined under an inverted phase contrast fluorescence microscope.

Alizarin red S staining assay

After 7 and 14 days of osteoblast differentiation on the 3D-printed scaffolds, the level of calcification was assessed using Alizarin Red S staining. All experiments were independently performed in triplicate (n = 3). At the end of the differentiation period, the osteogenic medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS. A 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution was used to fix the differentiated cells for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with deionized water after removing the PFA solution. The washed cells were stained with Alizarin Red S staining solution (#20003999, Sigma-Aldrich) for 40 min at room temperature. To remove nonspecific staining, the Alizarin Red S solution was removed, and the cells were washed three times with deionized water. The relative area of Alizarin Red S staining was measured utilizing ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

ALP activity assay

After 7 and 14 days of osteoblast differentiation on the 3D-printed scaffolds, ALP activity assays were performed. All experiments were independently performed in triplicate (n = 3). A commercially available kit (Senso-Lyte® p-nitrophenyl phosphate alkaline phosphatase assay kit, #AS-72146, AnaSpec Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) was used to evaluate ALP activity according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 200 µl/well of biological samples containing ALP was added and incubated at 25 °C for 60 min to detect osteogenic differentiation. Following incubation, 100 µl of stop solution was added to each well to stop the reaction. The absorbance of the resultant p-nitrophenol was measured using spectrophotometry at 405 nm. ALP activity was quantified based on a standard curve generated using the ALP standard provided in the kit.

Experimental animals

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University (Approval No. CNU IACUC-YB-2022-149) and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The modified Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines were followed in all study procedures. The study included 20 healthy 3-month-old male NZW rabbits (weight: 3.0–3.5 kg, Damool Science, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The rabbits were housed in a temperature-controlled air-conditioned room (20 ± 2℃) with a relative humidity of 50 ± 10% and a light-dark cycle of 12 h. During the entire study period, they were provided with a commercial rabbit diet (Damool Science). The 20 rabbits were divided into two groups: 10 animals to be sacrificed in week 4 and another 10 animals to be sacrificed in week 8. The experiment was performed on both forelimbs of all animals. The 20 forelimbs of the 10 animals assigned to each of weeks 4 and 8 were randomly divided into 4 groups, with 5 forelimbs in each group. The four experimental groups were the Control group (only critical-size defect), the No cells group (3D-printed scaffold), the ADSC-single cell group (3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-single cells), and the ADSC-spheroid group (3D-printed scaffold with ADSC-spheroids).

Anesthesia and surgical procedure

General anesthesia was achieved through intramuscular injection of 3 mg/kg of xylazine (Rompun®, Bayer Korea Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea) and 6 mg/kg of alfaxalone (Alfaxan®, Jurox, Australia). Inhalation anesthesia was maintained using isoflurane (Ifran Liq. 1–2%, Hana Pharm Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea). During the procedure, 0.9% N/S fluid (2–5 ml/kg/hr; Normal Saline Inj., JW Pharm Co., Gwacheon, Republic of Korea) was administered to facilitate blood circulation and prevent unexpected bleeding. Pain was controlled with subcutaneous injections of 10 mg/kg of tramadol (Tramadol HCl Huons Inj., Huons Co., Seongnam, Republic of Korea) and 3 mg/kg of ketoprofen (Ketopro Inj., Unibiotech, Anyang, Republic of Korea). To prevent infection, 10 mg/kg of enrofloxacin (Baytril® 50 Inj., Bayer Korea Co.) was injected subcutaneously.

After shaving, the surgical site was disinfected using a povidone-iodine solution and 70% ethanol. A longitudinal incision in the skin was made along the radius. By dissecting the surrounding muscles, the radius was exposed. A 20-mm radial defect was created along the marking using ultrasonic piezoelectric bone surgery equipment (Surgystar Plus, DMETEC Co., Bucheon, Republic of Korea). Each scaffold was implanted into the defect according to the experimental groups. The scaffolds were fixed to the remaining radius with 27-G surgical wires (Solco Biomedical Co., Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea). The dissected muscle was sutured with a 4 − 0 polyglyconate suture (Maxon®, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland), and the incised skin was closed with a 4 − 0 polyglycolic acid suture (SurgiSorb®, Samyang Co., Seongnam, Republic of Korea) (Fig. 8).

Implantation of the 3D-printed scaffold in a rabbit radial defect model. (a) Disinfection of the surgical area after shaving. (b) Longitudinal skin incision followed by dissecting the surrounding muscles along the radius. (c,d) Formation of a 20-mm long radial defect. (e) Implantation of each scaffold into the defect according to the experimental groups. (f) Suturing of the muscle and skin.

After surgery, 1 mg/kg of ketoprofen was administered subcutaneously for analgesia and as an anti-inflammatory, and 10 mg/kg of enrofloxacin was administered for as an antibiotic for 1 week. The surgical site was disinfected with povidone-iodine once daily to prevent infection, and a neck collar was placed on the rabbit until recovery was confirmed in order to prevent the animal from licking or damaging the surgical site. At 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation, anesthesia was induced as previously described, and a high concentration of inhalational anesthesia (isoflurane) was used for deep anesthesia. Euthanasia was performed via intravenous injection of 150 mg/kg of KCl (potassium chloride 40 injection, Dai Han Pharm Co.), and samples were harvested.

Radiographic evaluation

Forelimb radiographs were taken immediately before the rabbits were sacrificed. Micro-CT scans were performed on the samples after euthanasia. Micro-CT analysis employed a radiation level of 130 kVp and 60 µA using a microtomograph (SkyScan 1173, Bruker-CT, Kontich, Belgium). Measurements were collected using SkyScan 1173 control software (version 1.6, Bruker-CT) with a tube current of 60 µA and tube voltage of 130 kVp. A total of 800 high-resolution images were captured with a resolution of 2,240 × 2,240 pixels, a pixel size of 24.96 μm, and a rotation angle of 0.3° for a total of 180°, with an exposure time of 500 ms. Data Viewer (Ver. 1.5.6.2, Bruker-CT) was used to arrange the orientation of the section images, and Nrecon (Ver. 1.7.4.6, Bruker-CT) was used to perform section reconstruction. The NBV in the defect site was analyzed using CT Analyzer (Ver. 1.19.4.0, Bruker-CT). A region of interest (ROI) was established to minimize interference from the host bone. Grayscale values ranging from 68 to 255 denoted mineralized tissue, with values between 68 and 99 signifying newly mineralized tissue within the defects66. The NBV was calculated as the sum of newly formed bone volumes within the defect.

Histological evaluation

Calci-Clear™ Rapid (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, USA) was used to decalcify the samples after they had been fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h. The samples were subsequently dehydrated with a series of alcohol rinses before being embedded in paraplast (Sherwood Medical Industries, Deland, FL, USA). Embedded samples were sectioned to a thickness of 5 μm using a microtome (Cambridge Instruments, Germany). The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome (MT) for microscopic analysis. For histomorphometric analysis, MT-stained sections were scanned and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA). New bone areas were identified based on color thresholding and manually delineated as regions of interest (ROIs). The percentage of new bone formation was calculated as the ratio of new bone area to total defect area in each section. Three representative sections per sample were analyzed to ensure reproducibility and minimize sectioning bias.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). To evaluate the NBV on micro-CT and histological images, GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, MA, USA) was used to conduct one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Additional inquiries can be referred to the corresponding authors; the article contains the original contributions made in the study.

Change history

31 January 2026

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Acknowledgements section. It now reads: “This study was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1C1C1009798 and RS-2024-0045442640982119420101) and Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through Agriculture and Food Convergence Technologies Program for Research Manpower development funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (grant number: RS-2024-00398561).”.

References

Zeng, A., Li, H., Liu, J. & Wu, M. The progress of decellularized scaffold in stomatology. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 19, 451–461 (2022).

Pereira, H. F., Cengiz, I. F., Silva, F. S., Reis, R. L. & Oliveira, J. M. Scaffolds and coatings for bone regeneration. J. Mater. Science: Mater. Med. 31, 27 (2020).

Park, J. Y. et al. 3D printing technology to control BMP-2 and VEGF delivery spatially and temporally to promote large-volume bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B. 3, 5415–5425 (2015).

Baldwin, P. et al. Autograft, Allograft, and bone graft substitutes: clinical evidence and indications for use in the setting of orthopaedic trauma surgery. J. Orthop. Trauma. 33, 203–213 (2019).

Zhang, S. et al. Clinical reference strategy for the selection of treatment materials for maxillofacial bone transplantation: A systematic review and network Meta-Analysis. Tissue Eng. Regenerative Med. 19, 437–450 (2022).

Genova, T. et al. Advances on bone substitutes through 3D Bioprinting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7012 (2020).

Cancedda, R., Giannoni, P. & Mastrogiacomo, M. A tissue engineering approach to bone repair in large animal models and in clinical practice. Biomaterials 28, 4240–4250 (2007).

Bhattacharyya, A., Khatun, M. R., Narmatha, S., Nagarajan, R. & Noh, I. Modulation of 3D bioprintability in polysaccharide Bioink by bioglass nanoparticles and multiple metal ions for tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Regenerative Med. 21, 261–275 (2023).

Friedenstein, A. J., Chailakhyan, R. K., Latsinik, N. V., Panasyuk, A. F. & Keiliss-Borok I. V. Stromal cells responsible for transferring the microenvironment of the Hemopoietic tissues: cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation 17, 331–340 (1974).

Campagnoli, C. et al. Identification of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in human first-trimester fetal blood, liver, and bone marrow. Blood 98, 2396–2402 (2001).

Erices, A., Conget, P. & Minguell, J. J. Mesenchymal progenitor cells in human umbilical cord blood. Br. J. Haematol. 109, 235–242 (2000).

Zuk, P. A. et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13, 4279–4295 (2002).

Yamada, Y. et al. 3D-cultured small size adipose-derived stem cell spheroids promote bone regeneration in the critical-sized bone defect rat model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 603, 57–62 (2022).

Reddi, A. H. & Cunningham, N. S. Recent progress in bone induction by osteogenin and bone morphogenetic proteins: challenges for Biomechanical and tissue engineering. J. Biomech. Eng. 113, 189–190 (1991).

Lee, S., Choi, E., Cha, M. J. & Hwang, K. C. Cell Adhesion and Long-Term Survival of Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Prerequisite for Cell Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 1–9 (2015). (2015).

Colter, D. C., Class, R., DiGirolamo, C. M. & Prockop, D. J. Rapid expansion of recycling stem cells in cultures of plastic-adherent cells from human bone marrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 3213–3218 (2000).

Lee, S. I., Ko, Y. & Park, J. B. Evaluation of the osteogenic differentiation of gingiva-derived stem cells grown on culture plates or in stem cell spheroids: comparison of two- and three-dimensional cultures. Experimental Therapeutic Med. 14, 2434–2438 (2017).

Achilli, T. M., Meyer, J. & Morgan, J. R. Advances in the formation, use and Understanding of multi-cellular spheroids. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 1347–1360 (2012).

Lee, D. H. & Bhang, S. H. Development of Hetero-Cell type spheroids via Core–Shell strategy for enhanced wound healing effect of human Adipose-Derived stem cells. Tissue Eng. Regenerative Med. 20, 581–591 (2023).

Murphy, K. C., Fang, S. Y. & Leach, J. K. Human mesenchymal stem cell spheroids in fibrin hydrogels exhibit improved cell survival and potential for bone healing. Cell Tissue Res. 357, 91–99 (2014).

Bartosh, T. et al. (ed, J.) Aggregation of human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) into 3D spheroids enhances their anti-inflammatory properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 13724–13729 (2010).

Bhang, S. H., Lee, S., Shin, J. Y., Lee, T. J. & Kim, B. S. Transplantation of cord blood mesenchymal stem cells as spheroids enhances vascularization. Tissue Eng. Part A. 18, 2138–2147 (2012).

Roddy, E., DeBaun, M. R., Daoud-Gray, A., Yang, Y. P. & Gardner, M. J. Treatment of critical-sized bone defects: clinical and tissue engineering perspectives. Eur. J. Orthopaed. Surg. Traumatol. 28, 351–362 (2017).

Shen, F. H. et al. Implications of adipose-derived stromal cells in a 3D culture system for osteogenic differentiation: an in vitro and in vivo investigation. Spine J. 13, 32–43 (2013).

Lee, J. et al. Human adipose-derived stem cell spheroids incorporating platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and bio-minerals for vascularized bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 255, 120192 (2020).

Lee, J. et al. 3D printed micro-chambers carrying stem cell spheroids and pro-proliferative growth factors for bone tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 13, 015011 (2020).

Seol, Y. et al. A new method of fabricating robust freeform 3D ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110, 1444–1455 (2013).

Yeo, A., Sju, E., Rai, B. & Teoh, S. H. Customizing the degradation and load-bearing profile of 3D polycaprolactone‐tricalcium phosphate scaffolds under enzymatic and hydrolytic conditions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part. B: Appl. Biomat. 87B, 562–569 (2008).

Liu, N., Zhang, X., Guo, Q., Wu, T. & Wang, Y. 3D bioprinted scaffolds for tissue repair and regeneration. Front. Mater. 9, 925321 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Fabrication and characterization of porous Polycaprolactone scaffold via extrusion-based cryogenic 3D printing for tissue engineering. Mater. Design. 180, 107946 (2019).

Siddiqui, N., Asawa, S., Birru, B., Baadhe, R. & Rao, S. PCL-Based composite scaffold matrices for tissue engineering applications. Mol. Biotechnol. 60, 506–532 (2018).

Rosales-Ibáñez, R. et al. Assessment of a PCL-3D Printing-Dental pulp stem cells triplet for bone engineering: an in vitro study. Polymers 13, 1154 (2021).

Jiao, Z. et al. 3D printing of HA / PCL composite tissue engineering scaffolds. Adv. Industrial Eng. Polym. Res. 2, 196–202 (2019).

Kim, C. G. et al. Fabrication of biocompatible Polycaprolactone–Hydroxyapatite composite filaments for the FDM 3D printing of bone scaffolds. Appl. Sci. 11, 6351 (2021).

JEONG, K. J. et al. Successful clinical application of cancellous allografts with structural support for failed bone fracture healing in dogs. Vivo 33, 1813–1818 (2019).

Shanbhag, S. et al. Bone regeneration in rat calvarial defects using dissociated or spheroid mesenchymal stromal cells in scaffold-hydrogel constructs. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 12, 575 (2021).

Kronemberger, G. et al. (ed, S.) A synergic strategy: Adipose-Derived stem cell spheroids seeded on 3D-Printed PLA/CHA scaffolds implanted in a bone Critical-Size defect model. JFB 14 555 (2023).

Kusuma, G. D., Carthew, J., Lim, R. & Frith, J. E. Effect of the microenvironment on mesenchymal stem cell paracrine signaling: opportunities to engineer the therapeutic effect. Stem Cells Dev. 26, 617–631 (2017).

Potapova, I. A. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells support migration, extracellular matrix invasion, proliferation, and survival of endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 25, 1761–1768 (2007).

Zhao, N. et al. Exogenous signaling molecules released from aptamer-functionalized hydrogels promote the survival of mesenchymal stem cell spheroids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 12, 24599–24610 (2020).

Unagolla, J. M., Gaihre, B. & Jayasuriya, A. C. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 3D printed Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Dimethacrylate-Based photocurable hydrogel platform for bone tissue engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 24, (2023).

Dinescu, S. et al. Biocompatibility Assessment of Novel Collagen-Sericin Scaffolds Improved with Hyaluronic Acid and Chondroitin Sulfate for Cartilage Regeneration. BioMed Res. Int. 1–11 (2013).

Abd El-Aziz, A. M., El-Maghraby, A., Ewald, A. & Kandil, S. H. In-Vitro cytotoxicity study: cell viability and cell morphology of carbon nanofibrous Scaffold/Hydroxyapatite nanocomposites. Molecules 26, 1552 (2021).

Jafary, F., Hanachi, P. & Gorjipour, K. Osteoblast differentiation on collagen scaffold with immobilized alkaline phosphatase. Int. J. Organ. Transpl. Med. 8, 195–202 (2017).

Hashemibeni, B. et al. Comparison of phenotypic characterization between differentiated osteoblasts from stem cells and calvaria osteoblasts in vitro. Int. J. Prev. Med. 4, 180–186 (2013).

Gregory, C. A., Gunn, G., Peister, W., Prockop, D. J. & A. & An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal. Biochem. 329, 77–84 (2004).

Kim, Y. B. & Kim, G. H. PCL/Alginate composite scaffolds for hard tissue engineering: Fabrication, Characterization, and cellular activities. ACS Comb. Sci. 17, 87–99 (2015).

Langenbach, F. et al. Scaffold-free microtissues: differences from monolayer cultures and their potential in bone tissue engineering. Clin. Oral Investig. 17, 9–17 (2013).

Li, N. et al. Spontaneous spheroids from alveolar bone-derived mesenchymal stromal cells maintain pluripotency of stem cells by regulating hypoxia-inducible factors. Biol. Res. 56, 17 (2023).

Gurumurthy, B., Bierdeman, P. C. & Janorkar, A. V. Spheroid model for functional osteogenic evaluation of human adipose derived stem cells. J. Biomedical Mater. Res. 105, 1230–1236 (2017).

Villalona, G. A. et al. Cell-Seeding techniques in vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part. B: Reviews. 16, 341–350 (2010).

Ho, S. S., Hung, B. P., Heyrani, N., Lee, M. A. & Leach, J. K. Hypoxic preconditioning of mesenchymal stem cells with subsequent spheroid formation accelerates repair of segmental bone defects. Stem Cells. 36, 1393–1403 (2018).

Ho, S. S., Keown, A. T., Addison, B. & Leach, J. K. Cell migration and bone formation from mesenchymal stem cell spheroids in alginate hydrogels are regulated by adhesive ligand density. Biomacromolecules 18, 4331–4340 (2017).

Ho, S. S., Murphy, K. C., Binder, B. Y. K., Vissers, C. B. & Leach, J. K. Increased survival and function of mesenchymal stem cell spheroids entrapped in instructive alginate hydrogels. Stem Cells Translational Med. 5, 773–781 (2016).

Kang, B. J. et al. Collagen I gel promotes homogenous osteogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in serum-derived albumin scaffold. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 24, 1233–1243 (2012).

Lee, C. F. et al. 3D printing of Collagen/Oligomeric Proanthocyanidin/Oxidized hyaluronic acid composite scaffolds for articular cartilage repair. Polymers 13, 3123 (2021).

Jayatissa, N. U. & Bhaduri, S. 3D printed polymer scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. J. Emerg. Invest. 26, 2 (2019).

Marouf, N., Nojehdehian, H. & Ghorbani, F. Physicochemical properties of chitosan–hydroxyapatite matrix incorporated with Ginkgo biloba-loaded PLGA microspheres for tissue engineering applications. Polym. Polym. Compos. 28, 320–330 (2019).

Li, H., Tan, C. & Li, L. Review of 3D printable hydrogels and constructs. Mater. Design. 159, 20–38 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Three-Dimensional, MultiScale, and interconnected trabecular bone mimic porous tantalum scaffold for bone tissue engineering. ACS Omega. 5, 22520–22528 (2020).

Ma, P. X. Biomimetic materials for tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 60, 184–198 (2008).

Bilgili, H. K. et al. 3D-Printed functionally graded PCL-HA scaffolds with Multi-Scale porosity. ACS Omega. 10, 6502–6519 (2025).

Deshpande, M. V., Girase, A. & King, M. W. Degradation of Poly(ε-caprolactone) resorbable multifilament yarn under physiological conditions. Polymers 15, 3819 (2023).

Park, S. A., Lee, S. H. & Kim, W. D. Fabrication of porous polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite (PCL/HA) blend scaffolds using a 3D plotting system for bone tissue engineering. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 34, 505–513 (2010).

KIM, S. E., LEE, E., JANG, K., SHIM, K. M. & KANG, S. S. Evaluation of Porcine hybrid bone block for bone grafting in dentistry. Vivo 32, 1419–1426 (2018).

Jo, H. M. et al. Application of modified Porcine xenograft by collagen coating in the veterinary field: pre-clinical and clinical evaluations. Front. Vet. Sci. 11, 1373099 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1C1C1009798 and RS-2024-0045442640982119420101) and Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through Agriculture and Food Convergence Technologies Program for Research Manpower development funded by Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (grant number: RS-2024-00398561).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., K.J., S.S.K. and S.E.K. conceived of the project and designed the research. Y.C., K.J., S.L., Y.K., S.J., K.M.S., S.S.K. and S.E.K. performed the research. Y.C., K.J., S.L., S.S.K. and S.E.K. analyzed data. Y.C., K.J., S.L., S.S.K. and S.E.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University in Korea (Approval No. CNU IACUC-YB-2022-149).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chae, Y., Jang, K., Lee, S. et al. Bone regeneration using adipose derived stem cell spheroids within 3D printed scaffolds in a rabbit radial defect model. Sci Rep 15, 43954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25581-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25581-5