Abstract

Sphaeropteris lepifera, a rare and endangered species belonging to the family Cyatheaceae, is often referred to as a “living fossil” and possesses significant ornamental value. This study investigated the survival status of four wild S. lepifera populations, with a focus on the impact of different canopy densities on the growth of Sphaeropteris lepifera plantlets. Moreover, an ensemble model incorporating ten algorithms was developed to assess the potential suitable distribution ranges of S. lepifera current and future climate conditions. The results indicate the wild population of S. lepifera exhibits a declining trend, which poses a very high risk of extinction. Variations in canopy density have significantly altered the understory light environment, leading to disorganization in the chloroplast grana lamellae structure of S. lepifera under C1 (< 30%) canopy density. This disorganization results in damage to photosystem II, blockage of electron transfer, increased expression of chloroplast genes, and ultimately yellowing of the leaves, which contributes to overall slow plant growth. Predictions from the ensemble model suggest that current suitable habitats of S. lepifera are located along the coastlines of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces, as well as in Hainan and Taiwan, identified as preferred areas for reintroduction into the wild. The overall suitable distribution of S. lepifera is projected to shift northward, with an increase in total area under future climate conditions, except the extreme climatic conditions (SSP585, 2100). However, this expansion of the suitable habitat does not change the endangered status of S. lepifera, due to the factors such as interspecific competition, man-made interference, and species dispersal capabilities, etc. Therefore, mitigation efforts, including human interventions such as the reintroduction of plantlets, spore propagation, and artificial management of suitable areas, remain essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Human activities and global climate change are impacting ecosystem diversity and species’survival and distribution1. Rare and endangered species may face an even greater challenge for survival due to their greater vulnerability to environmental changes, restricted habitat types, low population densities, and small geographical ranges2. At present more than 35,000 plant and animal species are listed as threatened with extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)3. Some of these endangered plants are relict species that retain endemic and ancient genetic information that is significant for maintaining biodiversity because of their systematic isolation and age3.

Sphaeropteris lepifera is a rare and endangered tree fern belonging to the family Cyatheaceae4. This tree fern is Wild plant under Country protection (category II) and listed as endangered within China. It has excellent ornamental value due to its long trunk, umbrella-shaped crown and beautiful leaf scars, as well as edible and medicinal values, and is also of great value in speciation, evolution, biogeography, paleoclimatology, and paleontology, and therefore, it is referred to as “living fossil”4. S. lepifera, belonging to the genus Cyathea of the family Cyatheaceae and the entire genus Cyathea appeared 90 million years ago, in the Cretaceous period. However, it has largely become extinct since the Quaternary ice age, mainly in the form of a dramatic decline in population numbers and the continuing death of wild individuals due to the Geohistorical evolution, human activities and climate change, which lead to its present restricted distributional range. As a result now only a small number of S. lepifera survive in the south of China (Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangzhou, Taiwan), Philippines, Japan, etc5. Our research group has been committed to the research of the endangered mechanism of S. lepifera, and has established a technical system of spore germination of S. lepifera, and cultivated a large number of plantlets. The in situ restoration of the S. lepifera is planned to artificially expand the wild population of the S. lepifera and alleviate the endangered status, consequently it is quite necessary to strengthen the basic understanding and selection method of suitable habitat of S. lepifera.

Recent developments in species distribution models (SDM) have led to its increasingly application in endangered species conservation, including projection of suitable habitat and species distribution ranges6,7. For example, the SDM predict that it is necessary to overlap the future distribution of Manihot walkerae (Euphorbiaceae)with protected areas in the Mexico in order to identify areas that will be suitable for future conservation efforts8. And the endangered species Adansonia suarezensis was forecasted which is vulnerable to climate change and more than half the population in the future (the period 2050 to 2080) will be in regions unsuitable for the species9. Karichu et al. utilized MaxEnt and climate data to examine tree ferns in Africa’s past and future, which showed that different tree ferns exhibited varied climate change responses, and most tree ferns shifted ranges but stayed in refugial areas through the Pleistocene10. Previous studies also reported that the most potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera was predicted on northern Taiwan, on Yunnan and Guangxi, along the western and central coast of Guangdong, and on near shore islands south of these provinces5. However, assessment of suitable habitat for S. lepifera had generally focused on human activities, slope, and climatic variables such as temperature and precipitation5, as well as only MaxEnt model was used5. The neglect of light environment in these approaches can lead to inaccurate predictions and misplaced conservation efforts of habitat suitability for S. lepifera. Numerous researches have suggested that light environment has a critical impact on plant growth, development, and survival5, as a consequence it is necessary to take into account the light variables in the SDM of S. lepifera.

Conservation and rescue of a endangered species requires not only an accurate prediction of its suitable habitat but also a essential understanding of its unique environmental tolerances to support meaningful field restoration efforts5. The adaptability of species to the changes of light condition determines its distribution pattern and species abundance, in other words, the succession status of the species in the forest depends on the adaptability of its plantlets to different light environments11. Canopy density is an important environmental factor of woodland, which most directly affects the light condition in woodland12. The difference of forest canopy density leads to the the immediate change of forest light intensity. Plantlets growth under different canopy density shows different growth, physiological state and distribution pattern13. Human activities may cause the decrease of forest canopy and the increase of light transmittance, which is not conducive to the growth and survival of plantlets, and thus affect the regeneration and development ability of the population14. Studies have shown that Cycas hainanensis plantlets, a rare and endangered cycad species, were suitable to grow in semi-shaded forest environment, and the decrease of canopy density could improve the natural regeneration ability of C. Hainanensis population and alleviate the endangered situation of wild C. Hainanensis15. However, high canopy density resulted in low light conditions in the habitat of Parrotia subaequalis belonging to the family of Hamamelidaceae, an endangered plant, which greatly restricted the growth and development of its plantlets, and eventually led to a sharp decrease in the medium diameter individuals of wild population16. Therefore, the study of the effect of canopy density on the growth and development of endangered species plantlets is of great significance for the survival and degradation of plantlets in the field, and it is also an indispensable effort for the recovery of wild populations.

The protection and restoration of plant populations have always been the focus of botanists. S. lepifera, as an endangered plant with extremly high scientific research value, the protection and restoration of whose population has also been the focus of attention, but actually its decline has not been effectively mitigated. The previous investigation showed that both the adult and the plantlet of S. lepifera were quite sensitive to the change of light environment. Even if the healthy S. lepifera plants returned to a suitable wild habitat, they would slowly die due to the unsuitable habitat conditions. The understory environment was found to be more suitable for the survival and growth of the S. lepifera population, whereas the difference of canopy density would also affect the growth of the S. lepifera plantlets, even restrict the reproduction and survival of the population. Therefore, based on field investigation and literature review, the study analyzed and assessed (i) the community characteristics of the current wild S. lepifera population, (ii) the effects of different canopy densities on the growth of S. lepifera plantlets in current suitable habitats, and (iii) the dynamic trend of suitable habitat of S. lepifera population under climatic change. The purpose of this study is to provide theoretical guidance and technical support for the restoration of the wild population, expanding the wild population, and to promote the conservation of this endangered plants.

Results

Community characteristics of wild population of S. lepifera

The survival situation of four wild populations of S. lepifera in 2020 was presented in Table 1. All wild populations of S. lepifera are distributed within the subtropical marine monsoon climate region. In the Cangnan County habitat, there are two adult S. lepifera plants, where the dominant tree species in the community include Cinnamomum camphora and Laurocerasus zippeliana. The Taishun County habitat contains one mature plant (height 80 cm, ground diameter 20 cm) and more than ten plantlets of S. lepifera. The main herbaceous species in this area include Ardisia japonica, Pteris multifida, Cyperus rotundus, and Platycodon grandiflorus, while the primary tree species are Cyclobalanopsis glauca and Cinnamomum camphora. In the Xiapu County habitat, eight mature S. lepifera plants were recorded, of which two have died. The height of the surviving plants ranges from approximately 1.8 to 3.5 m, and the habitat was characterized by the presence of Dimocarpus longan, Sympodial bamboo, Oxalis corymbosa, and Cayratia japonica, among others. In Pingtan County, four S. lepifera plants exist, including one mature plant with a height of approximately 2.2 m, while the other three plantlets range from 10 to 40 cm in height. Pinus massoniana and various shrubs grow naturally in this distribution area, with thatch coverage estimated at around 80%. In 2023, a re-investigation of the survival status of four wild populations of S. lepifera revealed that only one mature S. lepifera remains in Cangnan County. In Taishun County, the number of mature S. lepifera has decreased from the original ten to just five. In Xiapu County, four of the original six mature S. lepifera are still present, while in Pingtan County, three out of four S. lepifera remain, and one seedling has died. All four wild populations of S. lepifera exhibit a significant decline, indicating an extremely high risk of extinction.

The phenotypic change and leaf anatomical structure of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

The growth of S. lepifera under different canopy densities over a three-month period is illustrated in Fig. 1A. The different canopy densities significantly influenced the growth of S. lepifera. The C1 treatment, characterized by open air conditions, resulted in yellowing leaves and a slow overall growth rate of the plant. In contrast, plantlets of S. lepifera under other canopy density treatments exhibited robust growth with lush green leaves. However, under the C4 treatment, the plantlets displayed a slightly spindly growth pattern. The canopy density significantly influenced the growth and development of the leaves of S. lepifera (Fig. 1B). Leaf thickness in S. lepifera varied significantly across different canopy densities, while both the upper and lower epidermis were well-developed. The palisade and spongy tissues of the leaves from S. lepifera growing under open-air conditions (C1 canopy density) were well-developed, with thickness significantly greater than that observed in other canopy density treatments. Higher canopy density corresponds to increased shading; consequently, the S. lepifera leaves tend to be developmental retardation, exhibiting thinner leaf tissue and undeveloped palisade tissue.

Plant phenotype and leaf anatomical structure of S. lepifera plantlets grown under different canopy densities. C1 (< 30%), C2 (30–50%), C3 (50–70%) and C4 (> 70%). (A) plant phenotype; (B) leaf anatomical structure. UE, upper epidermis; LE, lower epidermis; ST, spongy tissue; PT, palisade tissue; VB, vascular bundle.

The chloroplast ultrastructure of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

Chloroplasts serve as the sites for photosynthesis in plants, and their growth and development directly affect the photosynthetic efficiency. Notable variations in the shape and size of chloroplasts were observed in the plantlets of S. lepifera under varying canopy densities (Fig. 2). The grana lamellae are crucial for the light reactions of photosynthesis. Under the canopy density C1, S. lepifera exhibited a significantly higher number of chloroplasts compared to other treatments, which contained a substantial amount of thylakoid membrane structures; however, these membranes were highly irregular and disordered, exhibiting faults and defects. In contrast, the chloroplasts in the leaves of S. lepifera plantlets under C3 canopy density displayed a normal ultrastructure, characterized by well-organized stromal thylakoids and distinct stacking structures. Conversely, S. lepifera under C4 canopy density showed a reduction in the number of thylakoids, with the stacking structures appearing ambiguous. Overall, while intense light exposure increases the number of grana in the leaves of S. lepifera, it also induces structural disarray. Nevertheless, excessively shaded conditions result in a decrease in the number of grana and an ambiguous structure within the chloroplasts.

The chlorophyll fluorescence of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

The canopy density significantly influences the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of S. lepifera plantlets (Fig. 3). The Fv/Fm serves as an indicator of the primary light energy conversion efficiency of photosystem II (PSII). It was observed that S. lepifera plantlets subjected to the C1 treatment experienced stress conditions, as evidenced by their significantly lower Fv/Fm values compared to the other treatments (Fig. 3C). The Fv/Fm fluorescence image for S. lepifera plantlets is presented in Fig. 3B, illustrating that the leaves of S. lepifera in the open air (C1 canopy density) were markedly suppressed. Y(II) is the actual photochemical quantum efficiency of PSII; Y(NO) is the fluorescence and light-independent fundamental heat dissipation quantum efficiency in PSII; Y (NPQ) represents the quantum efficiency of heat dissipation, which is regulated byΔpH and xanthophyll. Y ( II ) + Y ( NPQ) + Y (NO) = 1. Notably, the Y (NO) value for S. lepifera decreased progressively with increasing canopy density, with the Y (NO) under the C1 canopy density being significantly higher than that of the other treatments. In contrast, under the canopy density conditions of C3 and C4, the Y (II) values for S. lepifera plantlets were greater than those observed in the other irradiation treatments. These results indicate that S. lepifera plantlets under the C1 treatment exhibited poor growth and pronounced photoinhibition.

The chlorophyll fluorescence of S. lepifera plantlets grown under different canopy densities. C1 (< 30%), C2 (30–50%), C3 (50–70%) and C4 (> 70%). (A) Dual-pam light response curve; (B) Image of Fv/Fm; (C) Value of Fv/Fm, different lowercase letters (a, ab, b, c) indicate the results of the significance analysis of differences.

The analysis of chloroplast gene expression of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

This study focused on the selection of genes associated with photosynthesis in the chloroplasts of the S. lepifera for gene expression analysis, with results illustrated in Fig. 4. The genes analyzed included psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, and psbT, which encode components of chloroplast photosystem II. Additionally, atpA and atpB were identified as genes encoding chloroplast ATP synthase, while ndhA and ndhB encode chloroplast NADH synthase. petA and petB were recognized as genes encoding components of the cytochrome complex, and rbcL encodes the large subunit of Rubisco enzyme. The results indicated that canopy density had a significant impact on the expression of chloroplast photosynthesis-related genes. Notably, the expression levels of psbB, psbC, psbD, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbL, and psbT were significantly higher in the C1 canopy density (open air) compared to the other treatment groups, while these levels were significantly lower in the C4 canopy density (the most shaded condition). Furthermore, the expression of atpA and atpB, which encode ATP synthase, was significantly elevated in the C1 canopy density relative to other treatments. Similarly, the expression levels of the genes ndhA, ndhB, rbcL, and petB were significantly higher in the C1 canopy density treatment compared to the other treatments, while the lowest expression levels were observed in the C4 canopy density, which represents extreme shade conditions.

The analysis of potential suitable distribution of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

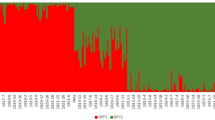

An ensemble model incorporating ten algorithms was employed to evaluate the potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera, with results illustrated in Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8. Initially, the modeling accuracy of each algorithm was assessed using ROC ( the true skill statistic) and TSS (the receiver operating characteristic curve) values, as depicted in Fig. 5. The analysis revealed significant difference in the accuracy of different algorithmic models when assessing the potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera. Specifically, the ROC values for the ten algorithms ranged from 0.84 to 0.98, while the TSS values varied between 0.68 and 0.95 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the mean analysis showed that the ROC and TSS values of the ensemble model were 0.92 and 0.83, respectively (Fig. 5B), demonstrating the superior performance of the ensemble model in predicting the potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera. The current range of potential suitable habitats of S. lepifera, along with the projected numerical changes under future climate scenarios, is illustrated in Fig. 6, which indicated that the suitable areas of S. lepifera are primarily concentrated in the coastal regions of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong provinces, as well as in Taiwan and Hainan provinces, covering a total area of approximately 404,000 square kilometers. However, ongoing environmental changes are expected to lead to fluctuations in the distribution of the S. lepifera under future climate conditions (see Figs. 7 and 8). This study indicated that the suitable habitat of S. lepifera is expected to expand northward to a certain extent under future climate conditions, resulting in an increase in its overall area (Fig. 8). Additionally, the potential distribution range of S. lepifera may also extend in partial areas of Yunnan and Tibet provinces (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, under extreme climatic scenarios (SSP585 (2100)), a notable reduction in the total area suitable of S. lepifera is anticipated.

Discussion

As an important endangered species, S. lepifera plays a crucial role in maintaining the stability and survival of natural vegetation communities, as well as the associated species within an ecosystem. Its presence serves as a reliable indicator of ecosystem health. Furthermore, the protection and restoration of S. lepifera in the wild provide significant guidance and serve as a model for conservation efforts.

Factors and causes of community composition affecting the growth of S. lepifera

S. lepifera is predominantly cultivated in Taiwan China. Although it is also found in regions such as Fujian, Hainan, Zhejiang, and Guangdong provinces, Taiwan remains its recognized primary place of origin. Historical records suggest that the S. lepifera present in the Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, as well as other areas, may have originated from Taiwan before dispersing to these locations17. As a “living fossil” within the plant kingdom, S. lepifera has ancient origins that date back to the time of the dinosaurs4. Throughout its existence, climatic changes have significantly influenced its habitat. Field surveys conducted in the Fujian and Zhejiang provinces indicate that wild populations of S. lepifera are predominantly found in mountainous and hilly regions, exhibiting a limited distribution range and small population sizes. Notably, there is a concerning scarcity of age-I plantlets, characterized by irregular distribution patterns; in some populations, no plantlets were observed at all. Surveys indicate that S. lepifera is typically found in humid understory areas or along the edges of forests, particularly near low-altitude ravines. This patchy distribution has emerged as a consequence of frequent human activities, including agricultural practices, forestry production, illegal harvesting, and natural selection pressures18,19,20. Collectively, these factors present significant challenges to the survival of S. lepifera populations, thereby contributing to their endangered status.

-

Field survey shows S. lepifera predominantly inhabit semi-shady slopes and shaded regions with a canopy density of 40% or greater and a slope gradient ranging from 0 to 20 degrees. Additionally, they are found sporadically in woodlands with a canopy density of less than 40%. However, in these areas, the S. lepifera plants display considerable burn damage, and there is a notable absence of plantlets. Light is a critical ecological factor that influences the survival, growth, and distribution of plants21. The survey results of the wild S. lepifera population further indicate that, in addition to human interference and interspecific competition, excessive light exposure accelerates the mortality of older S. lepifera and hinders plantlet reproduction22. These findings suggest that while S. lepifera can be sporadically found in areas with a forest canopy density of less than 40%, a canopy density of 40% or greater represents their most suitable light environment. Conversely, a canopy density of less than 40% has a significantly detrimental effect on the population growth of S. lepifera.

-

The distribution pattern of a population is intricately linked to its biological characteristics and the community environment in which it exists, resulting from the dynamic interactions between species and their surroundings23,24. The investigation revealed that the population renewal capacity of the wild S. lepifera is significantly constrained. In most communities, S. lepifera is not the dominant species, and the population of saplings is relatively low, primarily consisting of older trees with few plantlets. Furthermore, remnants of S. lepifera can be observed in many populations, indicating a declining trend in overall population renewal. The decline and eventual disappearance of wild populations of S. lepifera may be attributed to several interrelated factors. These include indiscriminate deforestation, interspecific competition, and challenges associated with plantlet reproduction25,26. S. lepifera, reproduces through spores. These spores require high humidity and ideal temperatures to germinate, conditions that are difficult to achieve in natural settings27. Moreover, the sporophyte of S. lepifera has a remarkably weak competitive survival capacity. As a result of these combined factors, the number of S. lepifera plantlets is limited, and the population’s regeneration ability is reduced. Additionally, environmental screening has contributed to the gradual decline and mortality of mature S. lepifera individuals, as well as plantlet regeneration failure.

Effect of canopy density (natural light environment) on growth of S. lepifera plantlet

The lighting conditions, relative humidity, temperature, and other environmental factors are crucial for plant growth and survival28. In natural environments, the spatial heterogeneity among forest gaps, understory areas, and open spaces is pronounced29. The formation of forest gaps enhances light availability beneath the canopy, which in turn elevates air temperature within the forest29. This alteration in temperature influences other environmental factors, such as humidity, ultimately modifying the local environmental dynamics of the forest. In open areas beyond the forest, light intensity surpasses that found in forest gaps and within the forest itself, reaching a peak of 1985.79 lx at 2 p.m. (Supplementary Material Fig.S1). These findings corroborate previous studies30, indicating that light intensity in forested regions varies significantly based on canopy density. Variations in canopy density create distinct microenvironments within the woodland, which profoundly affect the survival, succession, and persistence of plant populations31.

plantlets represent a highly sensitive stage in forest ecosystems and are particularly vulnerable to disturbances. Research on their adaptation and response to environmental factors can yield valuable insights into the capacity of plant populations for regeneration and persistence32. This study revealed that the growth of S. lepifera plantlets varies significantly across different canopy densities. In open-air conditions (canopy density C1 treatment), S. lepifera plantlets were stunted and exhibited yellowish leaves. Conversely, under other canopy density treatments, the plantlets thrive and display green leaves, indicating a distinct response to varying light conditions. The plantlets exhibited robust and verdant that align with the findings of Ma et al. regarding Camptotheca acuminata33, which suggested that lower canopy density enhances light conditions in the understory, leading to severe light scorching of S. lepifera plantlets. Such exposure can result in significant photoinhibition, thereby impeding the growth of these plantlets34. The anatomical structure of the S. lepifera leaves provides clear evidence of the species’ growth and development. Under the canopy density of C1, S. lepifera exhibits stunted growth attributed to thicker mesophyll tissue, whereas plantlets under other treatments possess thinner mesophyll tissue, resulting in a more slender and leggy appearance. This variation underscores the adaptability of S. lepifera plantlets to differing light intensities associated with various forest canopy densities.

Chloroplasts are the primary organelles responsible for light energy absorption and serve as the principal site for photosynthesis, thereby directly influencing the utilization of light energy by plants35. Adverse conditions, such as low light intensity, drought, and high salinity, can induce a series of structural changes in plant chloroplasts36. Previous research has indicated that inappropriate light intensity can also affect chloroplast structure36. This study observed that the stacked structure of chloroplasts in S. lepifera plantlets became disrupted, disordered, and blurred under high light conditions (C1 Canopy density). In contrast, chloroplasts in the leaves of S. lepifera under medium canopy density exhibited well-developed morphology and a clear, intact grana lamellar structure. Nevertheless, chloroplasts in the leaves of S. lepifera subjected to extreme shade conditions appeared blurred and incompletely developed. Similar findings have been reported in periwinkle37, soybean38, Camptotheca acuminata33, and other species, suggesting that under low canopy density, high light intensity can adversely affect the development of the photosynthetic organs in S. lepifera plantlets.

Chlorophyll fluorescence technology is extensively employed in the research of plant stress resistance physiology, providing valuable insights into the functioning of the photoreceptor photosystem II and its associated electron transfer processes39. This study revealed that the Y(NO) value of S. lepifera plantlets significantly increased under C1 canopy density, resulting in photoinhibition. Concurrently, the Fv/Fm value was notably lower compared to other canopy density conditions, indicating that the maximum photochemical quantum yield of S. lepifera was inhibited. The potential activity of PSII is diminished, suggesting that the S. lepifera plantlets are experiencing severe adversity stress and are situated in an unfavorable growth environment.

The chloroplast genes found in the leaves of S. lepifera include those coding for photosystem II (PSII), ATP synthase, NADH reductase, cytochrome complex, and Rubisco enzymes40. This study demonstrates that under varying densities of forest canopy, the expression levels of chloroplast genes such as psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbL, psbT, atpA, atpB, ndhA, ndhB, and rbcL exhibit an increase under C1 canopy density, while they decrease under C4 canopy density (extreme shade conditions). These findings suggest that variations in forest canopy density induce significant light environmental stress, resulting in protein damage to PSII. The upregulation of psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbL, and psbT facilitates the replacement of damaged PSII proteins with newly synthesized equivalents, thereby ensuring the continuation of photosynthesis in S. lepifera plantlets and alleviating the detrimental effects of excess light energy. Moreover, exposure to strong light conditions can lead to the degradation of thylakoid proteins in S. lepifera, hindering photoelectron transport and diminishing Rubisco enzyme activity, which ultimately contributes to the slow growth of S. lepifera plantlets.

The analysis of suitable habitat for Field recovery of S. lepifera population under different climate scenarios

Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that simulation predictions of species distributions can vary significantly across different single algorithm models41,42. Consequently, the application of ensemble models is increasingly recognized by a diverse array of researchers. This acknowledgment primarily stems from the capacity of ensemble models to mitigate the model selection bias associated with individual algorithms and to enhance prediction accuracy43. In this study, we developed an ensemble model that incorporates ten algorithmic approaches, alongside datasets of UV light environments and other environmental variables, to predict the potential suitable habitats for S. lepifera under current and future climatic conditions. These habitats are predominantly located along the coastlines of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong Provinces, as well as in Taiwan and Hainan Province. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Wei et al., which suggests that if the S. lepifera population were to be reintroduced into the wild, these areas would represent the most suitable options under current climatic conditions5. However, as mentioned above, the selection of suitable woodland should also take into account canopy density conditions to facilitate successful rewilding efforts. Furthermore, the ensemble model indicates that the potential suitable habitat for S. lepifera is likely to undergo significant alterations under future climate scenarios. Overall, the suitable habitat is projected to shift northward, with a trend of area expansion, potentially reaching parts of Yunnan Province and Tibet. This suggests that S. lepifera prefers a warm and humid growth environment, where shaded, warm, and humid habitats are more conducive to its growth and reproduction.

Previous studies have demonstrated that climate warming will lead to the expansion of tropical areas44,45, whereas most tree ferns in subtropical Atlantic Forest were predicted to lose suitable areas due to climate change46. In this study, under future climate scenarios, the potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera is anticipated to increase, likely as a direct consequence of climate warming. This result supports Karichu et al.’s conclusion that different tree ferns have different response patterns to climate change, ranging from minimal contraction to 57% expansion10. This phenomenon will enable a greater number of regions to meet the growth requirements of S. lepifera, particularly with respect to environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, and UV light conditions. However, the predictions regarding the expansion of S. lepifera’s potential distribution range must be interpreted with caution, as they do not necessarily imply that its endangered status will be alleviated. This is due to the influence of additional environmental driving factors, including interspecific competition, population renewal, and species dispersal abilities47,48. Moreover, the influence of varying canopy densities on the growth and development of S. lepifera species further underscores that light intensity is a critical environmental factor affecting the regeneration and expansion of S. lepifera populations. Consequently, human interventions, such as reintroducing artificially cultivated seedlings into natural habitats and managing the community environment, are essential. These interventions include implementing necessary shading measures to enhance the light conditions for S. lepifera populations, removing competing species to ensure sufficient growth space for S. lepifera, and effectively regulating environmental humidity, etc.

In summary, we investigated the survival status of wild populations of S. lepifera in Zhejiang, Fujian, and other regions. We explored the growth adaptability of S. lepifera plantlets under varying canopy densities and established an ensemble approach employing ten algorithms to predict the potential suitable distribution range of S. lepifera under current and future climate conditions. The results indicate that wild populations of S. lepifera is experiencing a gradual decline, indicating an extremely high risk of extinction. Our research on the growth environment of S. lepifera plantlets reveals that variations in light conditions, resulting from different canopy densities, significantly impact their growth and development. The strong light environment associated with lower canopy density damages the chloroplasts, PSII, and other photosynthetic organs of S. lepifera. This damage obstructs photosynthetic electron transfer, ultimately leading to yellowing leaves and stunted growth. Furthermore, under strong light conditions, chloroplast genes continuously replenish damaged thylakoid proteins through high expression, thereby maintaining the operation of the photosystem and mitigating the detrimental effects of strong light on S. lepifera. The evaluation of the ensemble model indicates that the potential suitable habitats of S. lepifera show a trend of northward expansion and an overall increase in area under future climate conditions, except the extreme climatic conditions (SSP585, 2100). This suggests that climate warming may enable additional regions to meet the environmental requirements necessary for the growth of S. lepifera. Nevertheless, this expansion of suitable habitat does not signify the alleviation of the endangerment status of S. lepifera, due to the influence of various other environmental driving factors, such as interspecific competition, population renewal, and species dispersal capabilities, human intervention remains essential. Moreover, the potential suitable habitats of S. lepifera are primarily concentrated in coastal areas, which are predominantly occupied by agricultural and residential lands. Therefore, efforts to promote the reestablishment of S. lepifera plantlets in the wild, to protect wild resources, and to establish dedicated protected areas or national parks in the predicted suitable habitats for S. lepifera are crucial strategies to ensure the survival and continuity of this species, as well as to mitigate its endangered status.

Materials and methods

Field survey of wild population of S. lepifera

The survey of four wild populations of S. lepifera was carried out in Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, including Cangnan County, (120° 60′ E, 27° 39′ N), and Taishun County (120° 51′ E, 27° 23′ N) of Wenzhou City, Xiapu County (119° 49′ E, 26° 42′ N), and Pingtan County (119° 47′ E, 25° 36′ N) of Fujian Province. The climate in the study area is a typical tropical monsoon climate with a mild, warm and humid climate, abundant sunshine and rainfall. A brief overview of the life cycle of the S. lepifera: S. lepifera is a spore-bearing plant that reproduces sexually via spores. For propagation, mature spores are uniformly sown in seedling trays with a substrate of fine peat or fine black soil (moisture content: 80–90%), then cultivated in an artificial incubator under controlled conditions: temperature 25 °C, relative humidity 60%, light intensity 66%. After 1 month of incubation, gametophytes (approximately 0.5 cm) emerge. By the 2nd month, sporophytes (approximately 1.5 cm) are fully formed. When seedlings reach 3–5 cm in height, they are cluster-transplanted to seedling pots and placed in a greenhouse. One-year-old seedlings (30–40 cm) are transplanted to shaded natural habitats. At 3 years of age, the plants grow to 70–80 cm; by the 5th year, the basal trunk becomes distinctly visible.

Sampling methods

The original habitat of S. lepifera wild population was investigated by the “Field measurement method” in 2020 first time. When the distribution area is narrow and the number of S. lepifera is small, the population is counted directly and the field survey is carried out by the measurement method. The “Field Survey method“ is to record the population with few individuals in the field, mainly recording the individual information (diameter at breast height, crown width, tree height, etc.) and environmental information (coordinate, canopy density, etc.). Select representative areas to establish quadrats, which will be surveyed every three months, resulting in a total of three surveys in 2020. Each wild population of S. lepifera will have six plots measuring 20m × 20m. Within each plot, five quadrats measuring 5m×5m will be set up, where all species must be surveyed. At the diagonals of each plot, a 1m×1m herbaceous quadrat will be established to record the number of species, average height, coverage, and species within the herbaceous quadrat. Additionally, a survey will be conducted to record the canopy density of the plot (Keith, 2000). Finally, spores will be collected from all mature S. lepifera within the wild population range and cultivated into sporophytes. Then three years later, to 2023, the number of S. lepifera surviving in 4 wild S. lepifera populations was investigated again.

Age structure analysis

The number of individuals of S. lepifera at all life stages as tree, sapling and plantlet were recorded. And the hight of tree measured using meter ruler. The ground diameter measured at 10 cm above the ground using measuring tape. All herbs and shrubs species present in the habitat of S. lepifera were recorded. According to the actual growth of the S. lepifera, which grows out of the trunk is an adult tree, the others are saplings or plantlets. And the individuals of S. lepifera were grouped into adult plant (the trunk formed, gd (ground diameter) > 10 cm, height > 80 cm), sapling (no trunk formed, gd < 10 cm, height > 80 cm) and plantlets (height < 80 cm).

The growth analysis of S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

The vigorous and uniform S. lepifera plantlets cultivated by us were selected and placed in the the wild habitats (Jingshan in Wenzhou, N28° 23′, E120° 72′) similar to those of the wild populations of S. lepifera, but with different canopy densities. Immediately, we used a Digital Lux Meter (TES-1339R, Taiwan) to measure the light intensity under different canopy densities, the results as shown in Supplementary Material Fig.S1, in which C1 represents the open air (canopy density < 30%); C2 represents the canopy density 30–50%; C3 represents the canopy density 50–70%; C4 represents the canopy density > 70%. Fifty S. lepifera plantlets were placed under each canopy density, distributed evenly in the sample field range of 20 m×20 m, totaling 200 plantlets. Three months later, the leaves of S. lepifera plantlets under different canopy densities were collected to measure their chlorophyll fluorescence49, chloroplast ultrastructure50, respectively.

Permission for collecting S. lepifera materials was obtained from the Zhejiang Subtropical Crop Research Institute. All S. lepifera materials utilized in this study were identified by Researcher Hongjian Liu (E-mail: solo1000@126.com). Voucher specimens of S. lepifera are deposited in the Herbarium of Wenzhou Jingshan Botanical Garden, with the voucher number BTS 11-1. The S. lepifera plants employed in this study were propagated from spores. These spores were collected by Qingdi Hu and Xiaohua Ma in Cangnan County, Zhejiang Province, and a subset of them is preserved as specimens in the Wenzhou Jingshan Herbarium under the accession number BTS12-1.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were assessed using the methodology outlined by Hendrickson et al. (2004), employing a portable Dual PAM-2500 Fluorometer from WALZ, Germany49. The leaves were dark-adapted for a period of 20 min prior to the assessment. Following this adaptation phase, a series of fast light curves were recorded at varying photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) levels, specifically at 0, 10, 18, 36, 94, 172, 214, 330, 501, 759, 923, 1178, and 1455 µmol m− 2 s− 1. The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were calculated using the following formulas: Y (II) = (F′m − Ft)/F′m; Y (NO) = Ft/Fm; and Y (NPQ) = (Ft/F′m) − (Ft/Fm). It is important to note that these parameters are interrelated such that the sum of Y (II), Y (NPQ), and Y (NO) equals 1. Each treatment was determined with 10 replicates, Statistical analysis was conducted using a One-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Data Processing System (DPS) software version 7.5, Duncan’s multiple range test was used to detect differences between means.

Additionally, the ultrastructure of chloroplasts was examined using a transmission electron microscope (H7650, Hitachi), following the protocols established by Zhang et al.50. Fresh leaf samples were meticulously diced and immediately fixed in a glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% v/v) buffered with 0.1 M phosphate at a pH of 7.4 for a duration of 24 h. Subsequently, the leaf samples underwent a thorough rinsing in a series of elutions. They were then subjected to post-fixation in osmium tetroxide (1% v/v) before being embedded in resin, which facilitated ultrathin sectioning for microscopy analysis.

The expression levels of chloroplast genes in S. lepifera plantlet under different canopy densities

qRT-PCR analysis was used to explore the response of the chloroplast genes in the leaves of the S. lepifera to different canopy densities. Total RNA was transcribed in reverse using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix Kit, which includes a gDNA wiper (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), following the guidance provided by the manufacturer. The qRT-PCR process utilized the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix Kit on a QuantStudio 3 system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PCR conditions included an initial step at 50 °C for 2 min, followed by 10 min at 95 °C, and then 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C, concluding with a melt curve analysis. The analysis of the relative expression levels of the target genes was conducted using the 2−∆∆Ct method50.

Prediction of potential suitable habitat of S. lepifera

The sampling points of S. lepifera with accurate longitude and latitude were shown in Supplementary Material and derived from (1) field investigation, (2) published relevant research papers and (3) publicly available species database, for example, Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org/), Chinese Virtual Herbarium (CVH, https://www.cvh.ac.cn/). Then the duplicates and outliers were eliminated. Next lowered the geographic autocorrelation of the sampling points through ENMtools. Eventually, 295 occurrence data in total of S. lepifera were chosen for modeling (Supplementary Material Table S1).

Two types of environmental datasets including climate dataset (temperature and precipitation) derived from WorldClim and UV-light dataset were used to assess the potential suitable distribution of S. lepifera (Table 2). The 19 climatic variables were shown in (Supplementary Material Table S2). The 6 UV-B variables (Supplementary Material Table S2) were derived from the monthly mean layers51,52. Then carried out the principal component analysis (PCA) of environmental variables including nineteen climatic variables and six UV-B variables base on the occurrence data of S. lepifera. Then eliminate the environmental variables with correlation coefficients > 0.8. Finally, eleven environmental variables inculding four temperature variables, four precipitation variables, and three UV-B variables were applied to modeling analysis (Table 2). The data of future climate scenario were obtained from the BCC-CSM1-1 (Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model, version 1-1) model in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, Phase 6 (CMIP6) at a 30 s spatial resolution including four climate scenarios (SSP126 (warming to below 2 °C by 2100), SSP245(warming by approximately 3 °C by 2100), SSP370 (intermediate scenarios) and SSP585 (worst case scenarios)) and four time periods (2021–2040, 2041–2060, 2061–2080 and 2081–2100). Then an ensemble model including ten algorithms, namely, (1) Artificial Neural Networks (ANN); (2) Classification Tree Analysis (CTA); (3) Generalized Linear Model (GLM); (4) Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS); (5) Flexible Discriminant Analysis (FDA); (6) Generalized Additive Models (GAM); (7) Generalized Boosted Models (GBM); (8) Random Forest (RF); (9) Maximum Entropy (MAXENT); and (10) Surface Response Envelope (SRE), as described by Zhao et al. (2021) were used to predict the current and future potential suitable habitats of S. lepifera.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- IUCN:

-

Union for conservation of nature

- SDM:

-

Species distribution model

- PSII:

-

Photosystem II

- Y (NPQ):

-

The quantum efficiency of heat dissipation

- CVH:

-

Chinese Virtual Herbarium

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- BCC-CSM1-1:

-

Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model, version 1-1

- CMIP6:

-

Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, Phase 6

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural networks

- CTA:

-

Classification tree analysis

- GLM:

-

Generalized linear model

- MARS:

-

Multivariate adaptive regression splines

- FDA:

-

Flexible discriminant analysis

- GAM:

-

Generalized additive models

- GBM:

-

Generalized boosted models

- RF:

-

Random forest

- MAXENT:

-

Maximum entropy

- SRE:

-

Surface response envelope

- TSS:

-

The true skill statistic

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

References

Huang, J. et al. Global desertification vulnerability to climate change and human activities. Land. Degrad. Dev. 31 (11), 1380–1391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3556 (2020).

Cai, C. et al. Predicting climate change impacts on the rare and endangered Horsfieldia tetratepala in China. Forests. 13 (7), 1051 (2022).

Pimm, S. L. & Plants What we need to know to prevent a mass extinction of plant species. People Planet. 3(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10160 (2021).

Hu, Q. et al. Complete chloroplast genome molecular structure, comparative and phylogenetic analyses of Sphaeropteris lepifera of Cyatheaceae family: a tree fern from China. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 1356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28432-3 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. Inferring the potential geographic distribution and reasons for the endangered status of the tree fern, Sphaeropteris lepifera, in Lingnan, China using a small sample size. Horticulturae 7 (11), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7110496 (2021).

Guisan, A. & Thuiller, W. Predicting species distribution: ofering more than simple habitat models. Ecol. Lett. 8, 993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00792.x (2005).

Zhao, Z. et al. Prediction of the impact of climate change on fast-growing timber trees in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 501, 119653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119653 (2021).

Garza, G. et al. Potential effects of climate change on the geographic distribution of the endangered plant species Manihot walkerae. Forests. 11 (6), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11060689 (2020).

Wilson, R. T. & Baobabs Adansonia spp.(Bombacaceae Malvaceae), around Antsiranana (Diego Suarez), Northern Madagascar. Biodivers. J. 9 (4), 395–398. https://doi.org/10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2018.9.4.395.398 (2018).

Karichu, M. J. et al. Tracing the range shifts of African tree ferns: insights from the last glacial maximum and beyond. Ecol. Inf. 84, 102896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.10-2896 (2024).

Chazdon, R. L. et al. Photosynthetic Responses of Tropical Forest Plants To Contrasting Light environments[M]//Tropical Forest Plant Ecophysiology, 5–55 (Springer US, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-1163-8_1

Abdollahnejad, A., Panagiotidis, D. & Surový, P. Forest canopy density assessment using different approaches-review. J. For. Sci. 63 (3), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.17221/110/2016-JFS (2017).

Popma, J. & Bongers, F. The effect of canopy gaps on growth and morphology of seedlings of rain forest species. Oecologia 75, 625–632 (1988).

Motta, R. & Nola, P. Growth trends and dynamics in sub-alpine forest stands in the varaita Valley (Piedmont, Italy) and their relationships with human activities and global change. J. Veg. Sci. 12 (2), 219–230 (2001).

Wang, C. et al. Genetic diversity and population structure in the endangered tree Hopea hainanensis (Dipterocarpaceae) on Hainan Island, China. PloS One. 15 (11), e0241452 (2020).

Li, W. & Zhang, G. F. Population structure and Spatial pattern of the endemic and endangered subtropical tree Parrotia subaequalis (Hamamelidaceae). Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants. 212, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2015.02.002.

Kuriyama, A., Kobayashi, T. & Maeda, M. Production of sporophytic plants of Cyathea lepifera, a tree fern, from in vitro cultured gametophyte. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 73 (2), 140–142. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs.73.140 (2004).

Referowska-Chodak, E. Pressures and threats to nature related to human activities in European urban and suburban forests. Forests. 10 (9), 765. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10090765 (2019).

Van Vliet, N. et al. Trends, drivers and impacts of changes in swidden cultivation in tropical forest-agriculture frontiers: a global assessment. Glob. Environ. Change. 22(2), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.009 (2012).

Lattimore, B. et al. Environmental factors in woodfuel production: Opportunities, risks, and criteria and indicators for sustainable practices. Biomass Bioenergy. 33(10), 1321–1342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.06.005. (2009).

Valladares, F. & Niinemets, Ü. Shade tolerance, a key plant feature of complex nature and consequences. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39 (1), 237–257. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707 (2008).

Salminen, A., Kaarniranta, K. & Kauppinen, A. Photoaging: UV radiation-induced inflammation and immunosuppression accelerate the aging process in the skin[J]. Inflamm. Res. 71 (7), 817–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-022-01598-8 (2022).

Panda, S. K. & Das, S. Potential of plant growth-promoting microbes for improving plant and soil health for biotic and abiotic stress management in Mangrove vegetation. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol.. 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-024-09702-6 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. Impact of climate change on the dynamic processes of marine environment and feedback mechanisms: an overview. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-024-10072-z (2024).

Hooper, E. R. The Effect of Forest Fragmentation on the biodiversity, Phylogenetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Community Structure of Seedling Regeneration in the Central Amazon: Area Effects and Temporal dynamics (Yale University, 2015).

Bas, T. G., Sáez, M. L. & Sáez, N. Sustainable development versus extractivist deforestation in Tropical, Subtropical, and boreal forest ecosystems: repercussions and controversies about the mother tree and the mycorrhizal network Hypothesis. Plants. 13 (9), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13091231 (2024).

Ravi, B. X., Varuvel, G. V. A. & Robert, J. Apogamous sporophyte development through spore reproduction of a South asia’s critically endangered fern: Pteris tripartita Sw. Asian Pac. J. Reprod. 4 (2), 135–139 (2015).

Amin, B. et al. Melatonin rescues photosynthesis and triggers antioxidant defense response in Cucumis sativus plants challenged by low temperature and high humidity. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 855900. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.855900 (2022).

Carey, A. B. & Wilson, S. M. Induced spatial heterogeneity in forest canopies: responses of small mammals. J. Wildl. Manag. 1014–1027 (2001).

Fahey, R. T. & Puettmann, K. J. Patterns in Spatial extent of gap influence on understory plant communities. For. Ecol. Manag. 255 (7), 2801–2810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.01.053 (2008).

Zangy, E. et al. Understory plant diversity under variable overstory cover in mediterranean forests at different Spatial scales. For. Ecol. Manag. 494, 119319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021 (2021).

Lindner, M. et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 259 (4), 698–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.023 (2010).

Ma, X. et al. Growth, physiological, and biochemical responses of Camptotheca acuminata seedlings to different light environments. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00321 (2015).

Didaran, F. et al. The mechanisms of photoinhibition and repair in plants under high light conditions and interplay with abiotic stressors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 259, 113004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2024.113004 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Tian, L. & Lu, C. Chloroplast gene expression: recent advances and perspectives. Plant. Commun. 4(5). (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Effects of different irradiance conditions on photosynthetic activity, photosystem II, Rubisco enzyme activity, Chloroplast ultrastructure, and Chloroplast-related gene expression in Clematis tientaiensis leaves. Horticulturae. 9 (1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9010118 (2023).

Farouk, S., Al-Huqail, A. A. & El-Gamal, S. M. A. Improvement of phytopharmaceutical and alkaloid production in periwinkle plants by endophyte and abiotic elicitors. Horticulturae. 8 (3), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030237 (2022).

Burkey, K. O. & Wells, R. Response of soybean photosynthesis and Chloroplast membrane function to canopy development and mutual shading. Plant Physiol. 97 (1), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.97.1.245 (1991).

Long, Y. & Ma, M. Recognition of drought stress state of tomato seedling based on chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. IEEE Access. 10, 48633–48642. 10.1109/ (2022). ACCESS.2022.3168862.

Zhang, C. et al. Chloroplast functionality at the interface of growth, defense, and genetic innovation: A multi-omics and technological perspective. Plants. 14 (6), 978 (2025).

Araújo, M. B. & New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22 (1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010 (2007).

Marmion, M. et al. Evaluation of consensus methods in predictive species distribution modelling. Divers. Distrib. 15, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642 (2009).

Crimmins, S. M., Dobrowski, S. Z. & Mynsberge, A. R. Evaluating ensemble forecasts of plant species distributions under climate change. Ecol. Model. 266, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.07.006 (2013).

Chen, I. C. et al. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science. 333 (6045), 1024–1026 (2011).

Senande-Rivera, M., Insua-Costa, D. & Miguez-Macho, G. Spatial and temporal expansion of global wildland fire activity in response to climate change. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 1208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28835-2 (2022).

De Gasper, A. et al. Expected impacts of climate change on tree ferns distribution and diversity patterns in subtropical Atlantic Forest. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 19.3, 369–378 (2021).

Fitzpatrick, M. J. & Edelsparre, A. H. The genomics of climate change. Science 359, 29–30. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3920 (2018).

Waldvogel, A. M. et al. Evolutionary genomics can improve prediction of species’ responses to climate change. Evol. Lett. 4 (1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.154 (2020).

Hendrickson, L., Furbank, R. T. & Chow, W. S. A simple alternative approach to assessing the fate of absorbed light energy using chlorophyll fluorescence. Photosynth. Res. 82 (1), 73–81 (2004).

Zhang, Y. et al. Leaf anatomy, photosynthesis, and chloroplast ultrastructure of Heptacodium miconioides seedlings reveal adaptation to light environment. Environ. Exp. Bot. 195, 104780 (2022).

Hijmans, R. J. et al. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276 (2005).

Kriticos, D. J. et al. CliMond: global high-resolution historical and future scenario climate surfaces for bioclimatic modeling. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00134.x (2012).

Funding

This project was supported by the Zhejiang Province Public Welfare Project (LGN22C020007), Conservation, breeding and wild return of germplasm resources of S. lepifera-Cangnan County Natural resources and planning Bureau (2024),Wenzhou Breeding Cooperation Group Project (No.ZX2024004-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.Z. and X.H.M.; Methodology: X.H.M.; Software: H.Y.W. and X.H.M.; Formal analysis: X.H.M.; Investigation: X.H.M. and Y.P.H., R.J.Q. and X.L.; Resources: Q.D.H. and Y.P.H.; Writing-original draft: X.H.M.; Writing-review and editing: X.H.M.; Visualization: X.L.; Supervision: X.L.Z.; Project administration: X.L.Z. and J.Z.; Funding acquisition: J.Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, X., Lu, X., Wang, H. et al. Population decline, potential habitat shifts, and growth reduction of the endangered tree fern Sphaeropteris lepifera in response to changing canopy density. Sci Rep 15, 41683 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25595-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25595-z