Abstract

Under cold shutdown conditions, the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipeline critically impacts pressurized water reactor (PWR) safety by governing residual heat removal efficiency. To quantify key drivers of thermal behavior during stagnant coolant operation, a high-fidelity thermal–hydraulic model is established by using the REALP5 MOD3.2 code. Systematic parametric analyses evaluate radiation effects and insulation-environment interactions through three dimensions. The results show that under stagnant coolant and zero-wind conditions, radiation contributes 90% of total heat transfer in the high-pressure coolant pipeline in the vertical direction, yielding a larger coolant temperature drop (ΔT) of 6.12 K over 86,400 s compared to the no-radiation model. Pipeline heat dissipation exhibits an inverse relationship with insulation cotton thickness but scales positively with material thermal conductivity. Within 800,000 s, when the insulation cotton thickness(δ) is reduced from 15 to 5 mm, the coolant temperature drops by nearly 18 K. This means that for every 10 mm reduction in the thickness of insulation cotton(δ), the heat dissipation efficiency increases by 40%. The coolant temperature drop (ΔT) of the pipe with asbestos insulation (thermal conductivity λ = 0.046W /(m·K)) reaches 43.98 K, which is 53.1% higher than that of the pipe with ultra-fine glass fiber cotton insulation(ΔT = 28.72 K) (thermal conductivity λ = 0.022W /(m·K)). Ambient temperature and airflow velocity exhibit inverse and positive correlations with coolant temperature drop (ΔT), the coolant temperature is reduced by 12.51 K more than the ambient temperature of 10℃ and 30℃. For every 1℃ decrease in ambient temperature, the temperature drop increases by 0.625 K. When the airflow velocity is 0.5 m/s compared to 0.1 m/s, the coolant temperature drops by 1.65 K more. This paper pioneers a high-fidelity thermo-hydraulic model of the main coolant pipeline of PWR under the stagnation condition after cold shutdown, which advances the theoretical framework of heat dissipation such as natural convection in the external environment and provides a quantitative safety margin for the removal of waste heat from the core. Further, it guides the design of insulation cotton material and the thickness of the high-pressure coolant pipeline and delivers predictive tools for the optimization of the heat dissipation strategy after cold shutdown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a key part of the cooling system of a pressurized water reactor (PWR), the high-pressure coolant pipe undertakes the important task of transporting high-temperature and high-pressure coolant, and its heat dissipation performance directly affects the thermal and hydraulic characteristics and safety performance of PWR1. During cold shutdown, the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe will change significantly compared with normal operation. On the one hand, the heat source intensity of the PWR core decreases greatly after shutdown2, and the temperature and flow rate of coolant in the high-pressure coolant pipe are also decreased. On the other hand, the insulation cotton of high-pressure coolant pipes and the environmental conditions around the high-pressure coolant pipe will change to a certain extent, and these factors will affect the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe. If the change of heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe is not fully considered or effective heat dissipation measures are not taken during the cold shutdown period, the temperature of high- pressure coolant pipe may be excessively high, which will affect the dissipation of the decay heat of the core, and even damage the structural integrity of high-pressure coolant pipes, which will lay a safety hazard for the subsequent operation of the PWR. It is of great practical significance to deeply study the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe of the PWR in the state of cold shutdown to ensure the safe operation of the PWR. Through the study of the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe, the change law of the temperature and heat flux of the high-pressure coolant pipe in the cold shutdown state can be accurately grasped, which provides a scientific basis for optimizing the maintenance efficiency of the shutdown and ensuring the safe operation of the nuclear reactor.

In the research field of cooling and heat dissipation of stainless steel pipe, the heat dissipation of the main pipe of PWR is always the focus of research. Domestic and foreign scholars have carried out a lot of research on the heat dissipation performance of the main pipe under different working conditions and different application environments, and have achieved fruitful results.

Hrnjak, PS et al.3 studied the heat transfer of three fluids commonly used as low-temperature coolants in the heat development zone of the round tube in the range of 0–40℃. The results showed that the positive effect on heat dissipation lasted for a long time in the case of high Nu value, and proposed the empirical formula for the optimal heat transfer in the laminar heat development zone. Alekseev, MV et al.4 conducted 3D simulations of fluid dynamics and heat transfer during the movement of Taylor bubbles in a capillary tube with a diameter of 2 mm in the velocity range of 0.05 to 0.5 m/s, and obtained the distribution of heat flux along the wall of bubble movement. The results showed that the thin film contributes to faster heat dissipation through evaporation compared to single-phase flow, a complex cascading re-circulation zone appeared near the bubble, and led to significant changes in heat flux near the wall. Solanki, Deepak K. et al.5 studied the local heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop in the horizontal tube of sub-cooled water boiling under low-pressure and high-mass-flux conditions, and developed an empirical correlation formula for the local heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop during the boiling process of sub-cooled flow. Wanwisa Rukthong et al.6 studied the heat transfer behavior between convection and conduction under laminar non-state flow in thick-walled crude oil pipelines. By using governing equations, statistical experimental design and response surface method, they studied the influence of wall thickness, wall thermal conductivity and surrounding temperature on the transmission profile. The results showed that the surrounding heat transfer coefficient and ambient temperature were important factors affecting heat transfer. In addition, Bibi, Bakhtawar et al.7 investigated the thermal performance of predicting time-dependent flow in a pipeline over multiple parameter ranges associated with the flow model and showed that the effect of increasing buoyancy parameters and viscous dissipation significantly improved flow velocity patterns and heat distributions throughout the basin.

Domestic scholars have also made remarkable progress in the research on the heat dissipation performance of stainless steel pipes. Mo Haiyang et al.8 studied a kind of stainless steel pipe with a sintered fiber core to improve the heat dissipation performance of stainless steel heat pipe in the spent fuel pool of a nuclear power plant. The effects of Angle, porosity and filling rate on the heat transfer performance of the pipeline were tested. The results show that porosity plays an important role in the power limit at 90° because gravity provides the necessary driving force. However, under the condition of 0°, the filling rate determines the space for steam flow, which has a great influence on the heat dissipation performance of the pipeline. Xu Ying9 studied the influencing factors of heat leakage in hot oil pipelines under shut-down conditions, measured the temperature field and solidification conditions of crude oil in pipelines under different shut-down conditions based on the additional capacity thermal calculation method, and determined the sensitivity of the main influencing factors through orthogonal experiments. The results showed that the order of importance of factors affecting heat dissipation is: crude oil initial temperature > insulation cotton thickness > air temperature > wax layer thickness. Guoxiang Wang et al.10 proposed a unified one-dimensional steady-state flow and heat transfer model for fluid transport in high-pressure pipelines. The model accounts for cooling and heat exchange from the surrounding environment. Qijin Zhao et al.11 proposed a method to measure the heat transfer parameters in a circular tube by considering the influence of insufficient turbulence development in the inlet region and the Robin boundary on the wall. The change of Nusselt number in the inner wall was calculated by measuring the temperature distribution of the outer wall. The temperature-dependent Gnielinski correlation was also developed for conditions where thermophysical parameters vary with fluid temperature. The results showed that as the flow distance increases, the deviation between the experimental Nusselt number and the predicted value using the traditional Gnielinski correlation becomes larger. The temperature-dependent correlation generally improved the prediction accuracy by more than 25%, and the prediction accuracy was higher with increasing inlet temperature and decreasing airflow speed. According to the heat transfer characteristics of steam pipe network and the external environment, Chen Baofa12 established the mathematical model of steam pipeline heat dissipation calculation, through the calculation and analysis of the heat transfer resistance of each link in the process of radial heat dissipation of the pipeline, the results show that the pipe diameter and the thickness of the insulation layer are the main factors affecting the heat dissipation of the pipeline. Li Yizhu et al.13 proposed a single fluid calculation method to solve the fluid–structure coupling heat transfer problem in nuclear power pipelines, and modified the heat transfer coefficient of the fluid domain boundary surface. The results showed that a single fluid numerical simulation can improve the calculation accuracy when it comes to the heat transfer problem of pipeline flow. For the high-temperature and high-pressure air pipeline, Xiao Shubo et al.14 established a pipeline thermal performance analysis model using aluminum silicate cotton as insulation material and carried out a simulation study. The results showed that the thermal conductivity of the insulation material was very different when the pipeline was running normally. The thermal conductivity of the inner side of the pipeline was close to 0.151W/(m · K), which was 7.5 times that of the outer side. The heat dissipation of the pipeline decreased with the increase of the thickness of the insulation layer, and the greater the thickness of the insulation layer, the smaller the influence of the thickness change on the change rate of heat dissipation of the pipeline is. Under the natural cooling condition, the cooling time of the pipe was long. It took 10 d for the pipe with a 200 mm thickness of the insulation layer to cool to 100 ℃, while it only took 90 min for the forced cooling of the pipe with normal temperature air. Liu Jialei et al.15 studied and analyzed the condensation heat transfer of whole steam on the inner wall of a transverse circular pass, and calculated the changes of condensate film thickness and heat transfer with flow distance under different cylinder radius. The results showed that the thickness of the condensate film only changed sharply at the upper and lower ends, and the total condensate heat transfer increased with the increase of the cylinder radius, but the heat transfer per unit area decreased with the increase of the cylinder radius. Li et al.16 developed a convective heat transfer characteristic model for the reactor system under ocean conditions, summarized a series of single-phase flow experiments in circular and rectangular channels under ocean motion, and analyzed and verified the heat dissipation model. The results showed that the existing models had limited application in different intervals of the Reynolds number. To optimize the heat transfer model, the time average value of the Nusselt number and the pulsation amplitude were considered and modified according to the mechanism and best fit of the existing experiments.

Although there are many achievements in the research of the heat dissipation performance of stainless steel main pipe at home and abroad, there are still some deficiencies in the research of the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe when the coolant does not flow after cold shutdown of PWR. The research on the influence factors of the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe under the cold shutdown state is not deep enough. There is a lack of systematic comparative analysis of the relationship between various factors and the comprehensive influence on heat dissipation performance whether radiation heat dissipation is considered or not. In addition, it fails to fully reveal the importance of insulation cotton thickness, ambient temperature, insulation cotton material and environmental forced convection on pipeline heat dissipation, which makes it difficult to meet the diverse engineering needs.

In this paper, the thermal–hydraulic model of the high-pressure coolant pipe of the PWR under the condition of cold shutdown is established based on the RELAP5 MOD3.2 program. Through theoretical analysis and numerical simulation, the change of the temperature and heat flux of the coolant in the high-pressure coolant pipe with time is deeply studied, and the difference in the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe under the condition of radiation heat transfer is explored. The influence of insulation cotton thickness, insulation cotton material, ambient temperature and ambient wind speed on the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe of nuclear PWR is systematically analyzed, which lays the foundation for ensuring the safety and formulating scientific and reasonable maintenance strategies during cold shutdown.

Theoretical analysis and pipeline heat dissipation model

As a key component of the PWR cooling system, the structure design and functional characteristics of the high-pressure coolant pipe play a decisive role in the safe and stable operation of the PWR. The straight pipe segment is the main component of the high-pressure coolant pipes, which is usually made of high-strength and corrosion-resistant austenitic stainless steel material. Its inner diameter and wall thickness are optimized according to the power and coolant flow of the PWR to meet the working requirements under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions.

Design parameters

As the key component of the PWR primary loop system, pipelines play a critical role in the reactor cooling system. Specifically, in the cold shutdown state, the decay heat level of the reactor is relatively lower, and the coolant in the primary loop pipelines is basically in a lower flow or even a stagnant state, leading to a relatively uniform temperature distribution in the main pipelines of PWR. Against this background, the single pipe could be reasonably selected as the simplified research object of the relatively complex pipelines of PWR. Specifically, the selected single pipe directly connects the reactor pressure vessel (RPV) and the steam generator (SG). The connection position of this pipe is as shown in Fig. 1.

The local single pipe of a pressurized water reactor is modeled as the research object, referring to the design parameters of the high-pressure coolant pipe of a certain type of pressurized water reactor, the outer diameter of the pipe is 0.325 m, the thickness of the pipe wall is 0.03 m, the length is 1 m, and the pipe material is stainless steel UNSS30200. The pipe is covered with glass wool that is 1.0 m long and 0.1 m thick. The physical properties of pipes, insulation cotton and air involved are shown in Table 1.

Simulation boundary

In the actual operation of the PWR main pipe, the processes such as coolant flow, heat transfer, and the interaction between the pipeline and the surrounding environment are very complex. Combined with the cold shutdown operation condition, the main gate valve is closed and the high-pressure coolant pipe is isolated. For the convenience of analysis and calculation, the coolant flow in the high-pressure coolant pipe is assumed to be a static, incompressible, single-phase flow. This means that small changes in the density of the coolant with temperature and pressure during the flow are ignored, thus simplifying the solution of the hydrodynamic equations. According to the actual situation, the material of the high-pressure coolant pipe is assumed to be uniform and isotropic, and its thermal physical properties, such as thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity, do not change with position and direction. The model boundary conditions are set in Table 2.

Modeling of pipeline heat dissipation

SCDAP/RELAP5/MOD3.2, the code used in this study, is derived from the coupling of RELAP5 (1997 release) and SCDAP. RELAP5 MOD3.2 is a highly versatile one-dimensional system thermal–hydraulic analysis program developed by the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (INEL), USA. It integrates a variety of general components, including pumps, valves, pipelines, accumulators, jet pumps, thermal components, point reactor kinetics models, and control systems. Additionally, it incorporates special process models such as sudden changes in flow cross-section, choked flow, reflooding heat transfer, countercurrent flow limitation (CCFL), and non-condensable gas transport—endowing it with the ability to accurately simulate transient processes in light water reactor (LWR) systems. The physical model of RELAP5 is based on the two-fluid six-equation system, and numerical solutions are obtained using semi-implicit or implicit difference schemes, which can effectively simulate the thermal–hydraulic phenomena in pipes.

Based on the RELAP5 MOD3.2 program, the thermal–hydraulic model of pipeline heat dissipation is constructed. Moreover, the geometric and physical models of the coolant pipe control volumes, the environmental control volumes, the stainless steel pipe heat structures and the insulation cotton heat structures are established. Consistent with the cylindrical structure of the pipeline, the fluid domain inside the pipe is modeled as a coaxial cylinder. The pipeline wall is also constructed as a cylindrical structure, closely surrounding the fluid domain. An additional cylindrical insulation layer is wrapped around the wall to simulate the actual thermal insulation design of the reactor pipeline. To reflect the actual working condition of the pipeline in the reactor containment, the external environment is modeled as a large constant-temperature space with stable pressure, ensuring no additional heat exchange interference beyond natural convection and radiation. According to the mechanism of its heat transfer characteristics, the axial and radial grids are divided, and the heat transfer boundary conditions are defined. The fluid inside the pipe is modeled using the pipe component of RELAP5. According to the flow stagnation characteristics of the coolant during cold shutdown, the fluid domain is divided into 10 lumped regions. This division balances computational accuracy and efficiency, avoiding excessive mesh density while ensuring the capture of local temperature changes. The pipeline wall and insulation layer are modeled using the cylindrical heat structure of RELAP5. For the wall: the axial direction is divided into 10 nodes; the radial direction is divided into 5 nodes, which correspond to specific positions in sequence: coolant-wall contact surface, pipe wall center, wall-insulation contact surface, insulation layer center, insulation-air contact surface. This radial node division effectively simulates the heat conduction process through multi-layer media. Figure 2 depicts the nodalization schematic of the vertically oriented pipeline, where CV403 is coolant, CV999 is environment, HS1403001 is stainless steel pipe, HS1403002 is insulation cotton, CV111 is the time-dependent volume of ambient air inlet and CV131 is the time-dependent volume of ambient air outlet.

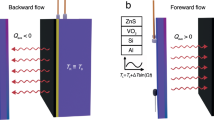

Physical model of pipeline heat dissipation

Heat transfer in the RELAP5 MOD3.2 program is implemented by the finite difference method. The grid intervals along the direction of heat transfer can exist at different distances and materials. The stainless steel pipe wall conducts heat radially from the inner wall to the outer wall, following Fourier’s Law of heat conduction. Additionally, the core focus of this study is to analyze the impact of insulation material or thickness on cooling performance. We adopt an ideal contact condition for the interface between the insulation layer and the steel pipe wall, we neglect the influence of air gaps that may arise from improper installation or vibration-induced detachment in practical engineering. The heat transfer models at this interface include heat conduction. The schematic diagram of the heat dissipation model of the high-pressure coolant pipeline is shown in Fig. 3.

This study investigates the full heat dissipation process of the high-pressure coolant pipeline, which includes heat exchange between the fluid and the pipe, heat exchange between the pipe and the insulation layer, and heat exchange between the insulation layer and the air. Specifically, the heat dissipation process of the pipeline includes the convective heat transfer and heat conduction between the fluid in the pipeline and the inner wall of the steel pipe, the internal heat conduction of the steel pipe, the heat conduction between the external surface of the steel pipe and the insulation layer, the internal heat conduction of the insulation layer, the convective heat transfer and radiation heat transfer between the external surface of the insulation layer and the ambient air. Assume that the inner diameter of the stainless steel pipe is r0, the outer diameter of the stainless steel pipe is r1, and the outer diameter of the insulation layer is r2.

Pipeline heat conduction model

As one of the basic ways of heat transfer, heat conduction plays a key role in the heat dissipation process of the high-pressure coolant pipe of a nuclear reactor. The heat conduction integral equation of the thermal component in the program is shown in Eq. (1).

where k is the thermal conductivity, W/(m · K). s is the surface area, m2. S is the internal heat source, W/m3. t is time, s. T is temperature, K. V is the volume, m3. x is the spatial coordinate. ρ be the density, kg/m3.

The boundary conditions on the outer surface are given in Eq. (2).

where n denotes the unit normal vector of the boundary surface. Therefore, for the ideal boundary condition, the heat outgoing from the surface of the thermal component is exactly equal to h (heat transfer coefficient) times the difference between the surface temperature T and the ambient temperature \({T}_{\infty }\), and Eq. (3) can be obtained.

By comparing Eq. (2) with Eq. (3), it can be obtained that.

Natural convection heat transfer model in the tube

The natural convective heat transfer coefficient h is related to the temperature difference between the outer wall of the pipe and the environment, the shape of the pipe and the physical properties of the air. For a vertical circular pipeline, it can be calculated by the Churchill-Chu empirical formula, as shown in Eq. (5) to (9).

where Nu1 is the Nusselt number of the coolant, Ra is the Rayleigh number, and Pr is the Prandtl number.

where Gr is the Grashof number.

where g is the acceleration due to gravity, which is 9.81 m/s2. β is the volume expansion coefficient of the fluid, k−1. D is the characteristic length, which is 0.65 m. Twall,in is the temperature of the inner wall of the pipe, K. Twall,out is the temperature of the outer wall of the pipe, K. \(\mu\) is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, m2/s. α is the thermal diffusivity of the fluid, m2/s.

where hnc is the heat transfer coefficient of natural convection, W/m2. Kcoolant is the thermal conductivity of the coolant.

where Qconv is the convective heat transfer, W.

Wall radiation heat transfer model

Since the thermal boundary conditions cannot be given in advance, the temperature of the coupled boundary surface is unknown and changes dynamically during the heat exchange, which cannot be solved separately17. According to the definition of effective radiation and input radiation, it can be known that the radiation heat dissipation of pipeline insulation cotton can be expressed as Eq. (10).

where Qrad is the heat dissipation by thermal radiation, W. ε is the surface emissivity of the thermal insulation cotton. σ is the Steffen Boltzmann constant, 5.67 × 10−8 W/(m2·K4). A is the area of the outer wall of the pipe, m2. Twall, out is the temperature of the outer wall of the pipe, K. T∞ is the ambient temperature, K.

Environmental natural convection heat transfer model

Natural convection occurs in the air around the pipeline. The influence of natural convection on the local heat flux distribution of the pipeline can be explained by the thermal boundary layer theory. When the solid wall is transmitted to the outside air, it will occur very clearly at a distance from the wall, and then in this area, the area of the unexpected temperature is flat, and the heat transfer process will be called the hot boundary layer of the local area with a 99% temperature drop. In the natural convection condition, the hot air that is close to the wall of the pipe wall will flow up along the wall of the pipe, which will lead to the thickness of the heat layer above the pipe top of the pipe greater than the bottom of the pipe, and the distribution of the pipe temperature and the density distribution of the heat flow will be uneven.

For the heat transfer experience of the vertical pipe axis, the natural convection experimental relationship of the large space can be adopted, as shown in Eqs. (11) and (12).

where Nu2 is the Nusselt number of the air, Pr is the Prandtl number, and Re is the Reynolds number.

where \(u\) is the flow velocity, m/s. \(d\) is the pipe diameter, m. \(\mu\) is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, m2/s.

A comprehensive Table of Symbols and Variables details each symbol’s definition, unit, and numerical value. Related parameters are listed in Table 3.

The influence of radiation heat transfer on the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe

In the research on the heat dissipation of vertical pipelines, the contribution of radiation heat transfer to heat transfer is often ignored or underestimated. In order to correctly evaluate the influence of radiation heat transfer on the heat dissipation of the pipeline, according to the actual working conditions of cold shutdown, the radiation model and the non-radiation model are selected to simulate the heat dissipation process of the vertical pipeline, and the mechanism of its action in the heat dissipation process of the vertical pipeline is deeply studied. The emissivity value adopted in the calculations with the radiation mode is 0.75 for glass wool.

It can be seen from Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 that in the simulation calculation of the radiation heat transfer model and the radiation heat transfer model without radiation, the temperature of insulation cotton gradually decreases with time, but the reduction rate is small and basically remains stable. Without considering the radiation heat transfer model, the initial temperature of insulation cotton is about 350.71 K, while considering the radiation heat transfer model, the initial temperature of insulation cotton is close to the initial temperature of the environment, and its value is about 295.73 K. Although there is a temperature difference between the insulation cotton and the environment, the heat cannot be effectively exported due to the lack of radiation heat dissipation. The initial heat flux of the outer wall of the pipe is low, about 0.3W/m2, and the temperature of the insulation cotton decreases by about 0.01 K at the end of the calculation. In the case of the radiation heat transfer model, heat can be transferred from the insulation cotton to the environment by thermal radiation. The initial heat flux density of the outer wall is about 14.7W/m2, and the temperature of the insulation cotton is reduced by about 0.1 K at the end of the calculation.

According to Figs. 6 and 7, the radiation heat transfer also has a significant influence on the coolant temperature change. When there is a radiative heat transfer model, the heat of the coolant can be transferred out through heat conduction, heat convection and heat radiation, and the temperature reduction rate is faster and the temperature reduction value is larger. However, in the case of a non-radiation heat transfer model, because the coolant is in a static state, the heat dissipation efficiency of the coolant is low, and the temperature drop rate is slow and basically remains stable. At the end of the calculation, the heat flux density of the inner wall with the radiation model is 18.2W/m2 and the heat flux density of the inner wall without the radiation model is 0.3557W/m2. Due to the heat transfer enhancement caused by radiation, the coolant temperature is reduced from 353.15 K to 346.94 K and 353.06 K, respectively. The temperature drop amplitude with radiation is 6.12 K more than that without radiation. Comprehensive analysis shows that the heat dissipation process of the pipeline covered with insulation cotton is mainly radiation heat transfer under the state of static coolant and no wind speed. Therefore, in the analysis and simulation of vertical pipeline heat dissipation, the contribution of radiation heat transfer to heat transfer cannot be ignored, and the radiation heat dissipation model should be considered in the heat dissipation analysis.

ax cvv

Influence of thermal insulation cotton on the heat dissipation characteristics of pipes

Insulation cotton is used to prevent the coolant pipeline from cooling too fast because of its low heat transfer coefficient. The thickness and material of insulation cotton are the main factors affecting the heat dissipation characteristics of insulation cotton, so it is necessary to analyze the heat transfer characteristics of insulation cotton in depth.

Influence of insulation cotton thickness on pipeline heat dissipation

In the high-pressure coolant pipe system of the PWR, the thickness of insulation cotton has a crucial impact on the heat dissipation of the pipeline. In the process of nuclear reactor operation, considering that the insulation cotton is affected by vibration, thermal expansion and contraction, it is easy to fall off and crack the insulation layer. At the same time, combined with the actual situation, the actual thickness of insulation cotton may change in the process of production, installation, use and maintenance of insulation cotton, which affects the temperature distribution of the pipeline and then affects the heat dissipation performance of the pipeline. In order to explore the influence of different insulation cotton thicknesses on pipeline heat dissipation under long-term cold shutdown conditions, five different insulation cotton thicknesses that may appear in actual operation, such as 5 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm, 12 mm and 15 mm, are selected for simulation calculation. Moreover, the radiation heat transfer model is maintained in an activated state throughout the simulations, consistent with the setup in Sect. “The influence of radiation heat transfer on the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe”, to ensure the accuracy of the heat transfer mechanism.

Different insulation cotton thicknesses lead to variations in thermal resistance. In the simulation of different insulation cotton thicknesses, the initial state difference of insulation cotton originates from the steady-state temperature distribution difference caused by varying insulation thermal resistance. This is consistent with the actual physical process, the thicker insulation with higher thermal resistance weakens heat transfer between the pipeline and the environment, resulting in a steady-state initial temperature of insulation cotton closer to the ambient temperature. According to Figs. 8 and 9, the initial temperature of insulation cotton with thicknesses of 5 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm, 12 mm and 15 mm is 298.97 K, 296.94 K, 296.27 K, 295.80 K and 295.33 K, respectively. The change trend of the temperature of insulation cotton with different thicknesses is similar to the change trend of heat flux on the outer wall. The thinner the insulation cotton, the greater the heat flux and the greater the change rate per unit time. However, with the increase of heat dissipation time, the heat flux on the outer wall gradually tends to be the same, about 6.0W/m2. The temperature of the insulation cotton also dropped to the same temperature, about 294.56 K. The reason is that in the initial stage of cooling, when the insulation cotton is thin, its thermal resistance is small, the heat flux density of the outer wall is large, and the heat dissipation is also large. With the increase of heat dissipation time, the temperature of the coolant in the pipe coated with the thinner insulation cotton is also higher, and gradually tends to be equal to the temperature of the coolant in the pipe coated with the thicker insulation cotton.

According to Figs. 10 and 11, different insulation cotton has a significant impact on the temperature drop rate and temperature drop amplitude of the coolant. The heat dissipation of the coolant in the pipeline decreases with the increase of the thickness of the insulation cotton, and the greater the thickness of the insulation cotton, the smaller the influence of the thickness change on the heat dissipation of the coolant in the pipeline. The initial temperature of the coolant in the pipeline is 353.15 K, and the temperature drop rate of the coolant in the pipeline is large in the initial stage. With the growth of the cooling time, the temperature of the coolant in the pipeline gradually decreases, and the temperature drop rate also gradually decreases. Moreover, the cooling rate of the coolant temperature in the pipeline is related to the thickness of the insulation cotton. The larger the thickness of the insulation cotton is, the smaller the cooling rate of the coolant temperature in the pipeline is at the initial stage. When the thickness of insulation cotton is 5 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm, 12 mm and 15 mm, the heat flux is 33.057W/m2, 22.961W/m2, 19.369W/m2, 16.963W/m2 and 14.437W/m2, respectively. Among them, the heat flux density of the inner wall of the pipeline coated with 5 mm insulation cotton is about 2.29 times that of the inner wall of the pipeline coated with 15 mm insulation cotton. The temperature change of the coolant is affected by the heat flux of the inner wall. When the thickness of the insulation cotton is 5 mm, 8 mm, 10 mm, 12 mm and 15 mm, the temperature of the coolant in the pipeline decreases to 304.73 K, 312.21 K, 315.94 K, 319.15 K and 322.63 K within 800000 s, respectively. Among them, the coolant temperature in the pipeline coated with 5 mm insulation cotton is reduced by 48.42 K, and the temperature reduction value is the largest. The coolant temperature in the pipeline covered by 8 mm, 10 mm, and 12 mm insulation cotton decreased by 40.94 K, 37.21 K, and 34.0 K, respectively, and the coolant temperature in the pipeline covered by 15 mm insulation cotton decreased by 30.52 K, with the smallest temperature reduction value. The change trend of the coolant temperature corresponds to the change trend of the heat flux of the inner wall surface. With the normal heat dissipation time, the heat flux of the inner wall surface decreases gradually per unit time. Although the initial heat flux of the pipe with thin insulation cotton is larger, its change rate is also larger. When the heat dissipation is about 730000 s, the heat flux of the pipe under the insulation cotton with each thickness is the same, which is 8.0338W/m2. The main reason is that with the increase of heat dissipation time, the temperature of the coolant in the tube decreases, which reduces the temperature difference between the inner and outer surfaces of the tube, thus reducing the real-time heat flux.

Influence of insulation cotton material on pipeline heat dissipation

At present, the research on thermal insulation engineering in the design stage of nuclear reactors abounds. The choice of pipeline thermal insulation material and structure plays a decisive role in the effect of thermal insulation engineering. However, it is necessary to note the functional difference of insulation cotton under different operating conditions: in PWR normal operation, it reduces heat loss to improve energy conversion efficiency; but under long-term cold shutdown, its high thermal insulation performance exerts a side effect—specifically, it inhibits the outward dissipation of residual heat from the pipeline, leading to a slower cooling rate of the coolant and a potential extension of shutdown maintenance time. Therefore, it is very important to study the heat dissipation performance of thermal insulation cotton material. According to the thermal insulation cotton materials commonly used in the current project, six kinds of thermal insulation cotton materials, such as ultrafine glass fiber wool, glass wool, polypropylene foam, rock wool, polyvinyl chloride foam and asbestos, are selected for heat dissipation simulation analysis. The radiation heat transfer model is maintained in an activated state throughout the simulations. The specific emissivity and thermal conductivity of these different materials18,19 are shown in Table 4.

Due to the different material skeleton of insulation cotton, he effective thermal conductivity and thermal resistance of insulation cotton are also different. In the simulation of different insulation cotton materials, the initial state difference originates from the steady-state temperature distribution difference caused by varying material thermal conductivities. The materials with lower thermal conductivity have higher thermal resistance, leading to a lower steady-state initial temperature of insulation cotton compared to materials with higher thermal conductivity. As shown in Figs. 12 and 13, the initial temperatures of ultrafine glass fiber wool, glass wool, polypropylene foam, rock wool, polyvinyl chloride foam and asbestos are 295.45 K, 296.27 K, 296.48 K, 296.77 K, 297.05 K and 297.19 K, respectively. In the initial stage, the larger the thermal conductivity of insulation cotton, the greater the heat flux of the outer wall, and the greater the rate of change per unit time. The initial heat flux of ultrafine glass fiber wool, glass wool, polypropylene foam, rock wool, polyvinyl chloride foam and asbestos-coated pipe outer wall is 10.021W/m2, 14.812W/m2, 16.094W/m2, 17.791W/m2, 19.468W/m2 and 20.281W/m2, respectively. The initial heat flux density of the external wall of the pipeline coated with asbestos with thermal conductivity of 0.046W/(m · K) is about twice that of the external wall of the pipeline coated with ultrafine glass fiber wool with thermal conductivity of 0.022W/(m · K). As the temperature of insulation cotton gradually tends to the ambient temperature, the temperature difference between the inner and outer sides of insulation cotton gradually decreases, and the heat flow on the outer wall gradually decreases. At the end of the simulation, the heat flux on the outer wall of different insulation cotton tends to 5.388W/m2.

It can be seen from Figs. 14 and 15 that the cooling properties of the coolant in the pipeline covered by different insulation cotton materials are very different. The heat dissipation of the coolant in the pipeline increases with the increase of the thermal conductivity of the insulation cotton, and the larger the thermal conductivity of the insulation cotton, the smaller the effect of the change of the effective thermal conductivity of the insulation cotton material on the heat dissipation of the coolant in the pipeline. The initial temperature of the coolant in the pipeline is 353.15 K. Due to the influence of temperature difference and thermal insulation cotton materials with different thermal conductivity, the temperature difference between the inner and outer walls of the pipeline is large in the initial stage, and the temperature drop rate of the coolant in the pipeline is large. With the growth of cooling time, the temperature of the coolant in the pipeline gradually decreases, and the temperature drop rate also gradually decreases. The variation trend of the heat flux on the inner wall is the same as that of the coolant temperature rate. The coolant temperature of ultrafine glass fiber wool, glass wool, polypropylene foam, rock wool, polyvinyl chloride foam and asbestos-coated pipes decreased to 324.43 K, 315.98 K, 314.17 K, 312.02 K, 310.09 K and 309.17 K within 800000 s, respectively. Among them, the coolant temperature in the pipe coated with ultrafine glass fiber wool is reduced by 28.72 K, and the temperature reduction value is the smallest. The coolant temperature of the pipe coated with asbestos decreased by 43.98 K, and the temperature decrease was the largest. According to the change trend of the heat flux of the inner wall, it can be analyzed that the temperature difference between the inner and outer walls of the pipe is the main influence on the heat flux of the inner wall. With the increase of the heat dissipation time, the temperature difference between the inner and outer walls of the pipe is gradually reduced, and the heat flux of the inner wall is also gradually reduced. The heat flux of the inner wall of the pipe coated with different insulation materials gradually tends to be the same, which is 8.5672W/m2.

Analysis of the effect of the environment on heat dissipation performance

As the external condition of pipeline heat dissipation, the environment is the final energy destination of pipeline heat dissipation, and different environmental conditions directly affect the ultimate capacity of heat dissipation. Therefore, in order to ensure the reliability of pipeline heat dissipation under the cold shutdown condition, it is necessary to deeply explore the factors as the environmental temperature and wind speeds. To avoid significant deviations in the analysis of environmental factors caused by ignoring radiative heat dissipation, all subsequent simulation studies below adopt the radiation model for calculation, where the radiation emissivity is set to 0.75.

Influence of ambient temperature of the stack chamber

As a key external condition in the process of pipeline heat dissipation, ambient temperature directly affects the heat exchange between the pipeline and the environment. By using the calculation program with a radiation model to simulate the heat dissipation of vertical pipelines, the difference in heat dissipation performance of pipelines under different ambient temperature conditions is studied. According to the working conditions of long-term cold shutdown, the ambient temperatures of 10℃, 15℃, 20℃, 25℃ and 30℃ were selected to simulate and calculate, respectively. The actual situation of pipeline heat dissipation was analyzed and explored through the changes of important parameters such as coolant temperature, heat flux density of pipeline wall and insulation cotton temperature under different ambient temperatures.

Different ambient temperatures set different thermal balance baselines for the system: in the simulation of different ambient temperatures, the initial state difference originates from the system’s steady-state heat balance starting point difference caused by varying external temperature baselines. Insulation cotton is between the coolant pipe and the environment, and its temperature is affected by both of them. Although the coolant temperature will affect the temperature of insulation cotton, when the ambient temperature is high, the temperature of insulation cotton is restricted by the ambient temperature more obviously, and the temperature of insulation cotton is less affected by the temperature change of coolant in a high-temperature environment. According to the basic principle of heat transfer, the heat transferred from the insulation cotton to the environment is relatively small. At the same time, the heat transfer from the coolant to the insulation cotton increases the temperature of the insulation cotton. Since the temperature difference between the coolant and the insulation cotton is relatively small, the heat transfer efficiency is also slow. It can be seen from Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 that the temperature of insulation cotton has a certain declining trend with time, and the higher the ambient temperature is, the higher the temperature of insulation cotton is, but the change is relatively gentle. After steady-state initialization calculation, the initial temperatures of insulation cotton are 286.97 K, 291.60 K, 296.25 K, 300.94 K and 305.63 K. The initial heat flux of the outer wall is 17.253W/m2, 16.035W/m2, 14.819W/m2, 13.589W/m2 and 12.358W/m2 under the ambient temperature of 10℃, 15℃, 20℃, 25℃ and 30℃, respectively. With the passage of heat dissipation time, on the one hand, the heat dissipation temperature of insulation cotton to the environment decreases, on the other hand, the temperature of coolant continues to decrease, so that the temperature difference between the coolant and the environment gradually decreases, the heat transfer power weakens, and the heat flux density of the outer wall gradually decreases. However, under the combined effect of the two, the temperature of the insulation cotton drops slightly and changes gently. When the ambient temperature is 10℃, 15℃, 20℃, 25℃ and 30℃, respectively, the heat flux of the outer wall decreases to 6.5857W/m2, 5.1175W/m2, 5.6540W/m2, 5.2183W/m2 and 4.7426W/m2, respectively. The temperature of insulation cotton decreased to 284.96 K, 289.84 K, 294.7 K, 299.59 K and 304.47 K, respectively, with a decrease of 1–2 K.

Figures 18 and 19 show the gradual decrease of coolant with time and the gradual decrease of heat flux on the inner wall of the pipe with time at different ambient temperatures, respectively. According to Newton’s law of cooling, the rate of heat dissipation of an object is proportional to the temperature difference between the object and the environment. The temperature of the coolant is higher than the ambient temperature. There is a temperature difference between the two, and the heat is transferred from the coolant to the environment through the pipe and the insulation cotton. In the initial stage, the temperature of the coolant is relatively stable at 353.15 K, while the lower the ambient temperature, the greater the temperature difference between the coolant and the environment, and the stronger the driving force of heat transfer. At this time, the larger temperature difference is the faster rate of heat transfer from the coolant to the inner wall of the pipe, which is manifested by the larger initial heat flux value of the inner wall. With the advancement of the heat dissipation process, the temperature of the coolant decreases gradually, the temperature difference between the coolant and the environment decreases gradually, the heat transfer power weakens, and the heat flux density of the inner wall decreases. When the ambient temperature is low, the initial temperature difference is large, the heat transfer rate is fast, and the temperature of the coolant decreases rapidly, so that the temperature difference decreases faster, and then the heat flux density of the inner wall decreases faster. At the end of the calculation, when the ambient temperature is 10℃, 15℃, 20℃, 25℃ and 30℃ respectively, the coolant temperature drops to 309.81 K, 312.85 K, 316.04 K, 319.31 K and 322.32 K respectively. Among them, when the ambient temperature is 10 degrees Celsius, the cooling temperature drops by 43.34 K, the temperature drop value is the largest, and the heat dissipation is the best. However, due to different ambient temperatures, the heat flux of the inner wall remains relatively high at lower ambient temperatures. When the ambient temperature is 10 degrees Celsius, the heat flux of the inner wall is 8.6229W/m2. When the ambient temperature is 30 degrees Celsius, the heat flux of the inner wall is 6.3158W/m2.

Influence of natural convection heat transfer of ambient air

Natural convection is easy to occur in the environment around the high-pressure coolant pipe of the PWR due to the flow of air, and the influence of convective heat transfer on the heat flux distribution of the pipe cannot be ignored. The program of the environmental natural convection model was used to simulate the heat dissipation of vertical pipes under different airflow velocities. According to the long-term cold shutdown state, the natural convection in the reactor environment is generally generated by a small wind speed. The typical working conditions of the airflow velocity in the environment are selected as 0.1 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.3 m/s, 0.4 m/s, 0.5 m/s. Through the changes of the important parameters such as the temperature of coolant, the heat flux density of the pipe wall and the temperature of the insulation cotton under different airflow velocity, the influence law of the airflow velocity on the heat dissipation characteristics of the pipe was deeply analyzed and explored.

Different airflow velocities alter the initial convective heat transfer intensity. In the simulation of different airflow velocities, the initial state difference originates from the steady-state heat exchange rate difference caused by varying initial convective heat transfer intensity. The higher airflow velocities increase the convective heat transfer coefficient of the insulation outer surface, resulting in a higher initial outer wall heat flux compared to the lower velocities. As shown in Figs. 20 and 21, a rapid decrease in outer wall temperature and heat flux occurs at the initial simulation stage. This is due to the maximum temperature difference between the pipeline and the environment at t = 0, resulting in a strong thermal driving force. The higher the airflow velocity, the greater the convective heat transfer coefficient, and the more pronounced this initial drop appears. The system subsequently enters a gradually varying quasi-steady cooling process. This phenomenon is more pronounced at higher airflow velocities, reflecting the physical transient response of the system. When the airflow velocity in the environment is 0.1 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.3 m/s, 0.4 m/s and 0.5 m/s, the initial heat flux of the outer wall of the pipeline is 78.871W/m2, 83.965W/m2, 85.522W/m2, 86.262W/m2 and 87.213W/m2. At the initial stage, the temperature of the insulation cotton is relatively high, which is 309.32 K. With the passage of time, the heat inside the pipe is continuously lost, and the temperature is gradually reduced, so that the temperature difference between the inside and outside is reduced. At high airflow velocity, the heat flux density of the outer wall decreases faster due to the rapid heat transfer. The heat flux on the outer wall of the pipe decreases to 56.208W/m2, 58.503W/m2, 59.368W/m2, 59.8231W/m2, and 60.1020W/m2. And the temperature of insulation cotton decreased to 297.18 K, 294.75 K, 293.82 K, 293.33 K, 293.02 K, respectively. The convection heat transfer process of the outer wall of the pipeline is directly affected by the air flow velocity. When the air flow velocity increases, the convection heat transfer coefficient of the outer wall increases. According to the theory of convection heat transfer, when the temperature difference between the outer wall of the pipeline and the environment is constant with the heat transfer area of the outer wall, the heat flux density of the outer wall also increases.

According to Figs. 22 and 23, the coolant temperature shows a continuous decline trend over time, and the difference in airflow velocity changes the rate of its decline. When the airflow velocity in the environment is 0.1 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.3 m/s, 0.4 m/s and 0.5 m/s, the initial heat flux of the inner wall is 75.677W/m2, 75.131W/m2, 74.342W/m2, 72.885W/m2, 69.169W/m2, and the initial temperature of the coolant in the pipeline is 353.15 K. At the initial stage, the difference of coolant temperature drop under different airflow velocities is not obvious. With the passage of heat dissipation time, the larger the airflow velocity is, the larger the coolant temperature drop rate is, and the larger the temperature drop amplitude is. Because the high airflow velocity promotes the heat transfer between the coolant and the inner wall of the tube, and accelerates the heat loss to the outside, the heat exchange on the inner wall is more intense. With the heat dissipation process, the temperature of the coolant is gradually reduced, the temperature difference between the inner and outer walls of the tube is gradually reduced, and the heat flux on the inner wall is also gradually reduced. When the airflow velocity in the environment is 0.1 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.3 m/s, 0.4 m/s and 0.5 m/s, it is calculated to 86400 s. The heat flux of the inner wall decreased to 56.2721W/m2, 55.9824W/m2, 55.5566W/m2, 54.7592W/m2, 52.6155W/m2, respectively. The coolant temperature decreased to 333.47 K, 332.58 K, 332.15 K, 331.95 K and 331.82 K, respectively.

Conclusion

This study establishes a high-fidelity thermal–hydraulic model for PWR high-pressure vertical piping under cold shutdown. Through theoretical analysis and numerical simulation, the change law of the temperature and heat flux of the coolant in the high-pressure coolant pipe with time is deeply studied, and the difference of heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe with or without radiation heat transfer is explored. The influence of insulation cotton thickness, ambient temperature, insulation cotton material and environmental forced convection on the heat dissipation performance of the high-pressure coolant pipe of the PWR is systematically analyzed, and the following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

Under stagnant coolant and zero-wind conditions, radiation contributes 90% of total heat transfer in the high-pressure coolant pipeline in the vertical direction, yielding a larger coolant temperature drop (ΔT) of 6.12 K over 86,400 s compared to the no-radiation model. It indicates the key role of radiative heat transfer in the process of residual heat removal.

-

(2)

Pipeline heat dissipation exhibits an inverse relationship with insulation cotton thickness but scales positively with material thermal conductivity. Within 800,000 s, when the insulation cotton thickness(δ) is reduced from 15 to 5 mm, the coolant temperature drops by nearly 18 K. This means that for every 10 mm reduction in the thickness of insulation cotton(δ), the heat dissipation efficiency increases by 40%. The coolant temperature drop (ΔT) of the pipe with asbestos insulation (thermal conductivity λ = 0.046W/(m·K)) reaches 43.98 K, which is 53.1% higher than that of the pipe with ultra-fine glass fiber cotton insulation(ΔT = 28.72 K) (thermal conductivity λ = 0.022W/(m·K)). Therefore, according to the actual working conditions, it is necessary to choose the appropriate insulation cotton material, not only to ensure the insulation effect during operation, but also to consider the pipeline heat dissipation performance in cold shutdown conditions.

-

(3)

Ambient temperature and airflow velocity exhibit inverse and positive correlations with coolant temperature drop (ΔT), the coolant temperature is reduced by 12.51 K more than the ambient temperature of 10℃ and 30℃. For every 1℃ decrease in ambient temperature, the temperature drop increases by 0.625 K. When the airflow velocity is 0.5 m/s compared to 0.1 m/s, the coolant temperature drops by 1.65 K more. It is concluded that the lower the ambient temperature is, the faster the coolant temperature drop rate will be, which is conducive to ensuring the safety of pipeline heat dissipation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Haiqi, Z. et al. Analysis on waterproofing design in CCS pump building of PWR under main feed water pipe broken accident. Prog. Nucl. Energy 149, 104264 (2022).

Gou, J. et al. Analysis of loss of residual heat removal system for CPR1000 under cold shutdown operation. Ann. Nucl. Energy 105, 25–35 (2017).

HrnjakHong, P. S. S. H. Effect of return bend and entrance on heat transfer in thermally developing laminar flow in round pipes of some heat transfer fluids with high prandtl numbers. J. Heat Transfer 132(6), 061701 (2010).

AlekseevVozhakov, M. V. I. S. 3D numerical simulation of hydrodynamics and heat transfer in the taylor flow. J. Eng. Thermophys. 31(2), 299–308 (2022).

Solanki, K. D. et al. Subcooled flow boiling in a horizontal circular pipe under high heat flux and high mass flux conditions. Ann. Nucl. Energy 212, 111030 (2025).

Rukthong, W. et al. Integration of computational fluid dynamics simulation and statistical factorial experimental design of thick-wall crude oil pipeline with heat loss. Adv. Eng. Softw. 86, 49–54 (2015).

Bibi, B. et al. Dynamic behavior of mixed convection heat transfer among horizontal co-axial fixed pipes at varying temperatures: Efficiency of cylindrical heat sink. Alex. Eng. J. 94, 44–54 (2024).

Haijun, M. et al. Experimental study on the heat transfer performance of a stainless-steel heat pipe with sintered fiber wick. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl. 14, 1–16 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Sensitivity analysis of heat dissipation factors in a hot oil pipeline based on orthogonal experiments. Sci. Prog. 103(1), 36850419881866 (2020).

Wang, G. X. & Prasad, V. Unified, integral approach to modeling and design of high-pressure pipelines: Assessment of various flow and temperature models for supercritical fluids. J. Fluids Eng.: Trans. ASME. 147(2), 021402 (2025).

Qijin, Z. et al. Experimental study on the forced convection heat transfer characteristics of airflow with variable thermophysical parameters in a circular tube. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 40, 102495 (2022).

Baofa Chen. Research on Heat Dissipation Analysis and Optimization Design of Industrial Heating Steam Pipeline [D]. China university of measurement. (2021).

Yizhu, L. et al. Single-fluid method for fluid-structure coupling heat transfer in pipeline. Ship Sci. Technol. 37(09), 110–115 (2015).

Shubo, X. et al. High temperature and high pressure air pipe cooling characteristics simulation. J. Xiangtan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 44(01), 107–115 (2022).

Jialei, L., Qi, C. & Yuqing, C. Heat transfer analysis of steam condensation on the inner wall of a transverse cylinder. J. Nav. Univ. Eng. 30(02), 109–112 (2018).

Dong, L., Weicheng, L. & Ting, Y. Comparison and optimization of heat transfer models in reactor channel under the rolling condition. Nucl. Eng. Des. 395, 111859 (2022).

LIANG Xin. Study on Natural circulation Characteristics of Waste heat removal System of gas-cooled micro-reactor [D]. Harbin Engineering University, (2024).

Eshrar, L., Rachel, B. & Tom, W. Thermal Insulation Materials for Building Applications[M]. ICE Publishing https://doi.org/10.1680/TIMFBA.63518 (2019).

Bahadori, A. Thermal Insulation Handbook for the Oil, Gas, and Petrochemical Industries[M]. Gulf Professional Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800010-6.00003-4 (2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. And all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The specific contributions are as follows: Fulong Tang: Writing-original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation. Wei wang: Conceptualization, Writing-review &editing, Methodology. Yiming Luo: Project administration, Resources. Yuqing Chen: Supervision Baoshun Yan: Software, Investigation. Shanshan Liu: Software, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, F., Wang, W., Luo, Y. et al. Numerical simulation of heat dissipation characteristics in PWR high-pressure coolant pipes during cold shutdown. Sci Rep 15, 41685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25598-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25598-w