Abstract

Landform classification studies are prerequisites for recognizing regional geomorphic patterns and are urgently needed to explore the process of landform development and evolution. Taking the Tibetan Plateau as the study area, this paper proposes new geomorphologic classification methods and indicators, such as slope-cost distance and mountain undulation, considering the global topographic features and the integrity of geomorphologic objects. On this basis, the classification of geomorphic types on the Tibetan Plateau was completed. The results show that: (1) The proportion of plains within the mountainous Tibetan Plateau has reached 25%, with the ratio of the mountain and plain areas close to 3:1, and the mountain types are dominated by low-relief mountains and middle-relief mountains. (2) The spatial distribution of the plains is characterized by high fragmentation and low spatial aggregation, with an overall dispersed distribution “from inside to outside”. (3) The mountains form an overall topographic skeleton of “three horizontal and one vertical” and the global landform pattern of the Tibetan Plateau is complex and diverse. The outcomes can provide a reference for digital terrain analysis and landform classification-related studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Landform is a dominant factor governing the occurrence and development of surface processes on the Earth, reflecting the objective geometrical characteristics of the surface and the ultimate expression of the long-term integrated action of the Earth’s internal and external forces on the surface1,2. Landform classification divides landforms based on certain classification principles and indicators and uses specific classification methods, which define geographic boundaries for the study of geomorphology, hydrology, soil science, and other related fields3. As a basic theoretical issue in geomorphology, landform classification reflects the morphology, genesis, and development of landforms, and serves as the foundation for regional landform analysis4. Hence, landform classification holds great significance in optimizing resource allocation, coordinating regional economic development and other issues of national economic construction.

The Tibetan Plateau region is a hotspot for landform classification research in China, receiving extensive attention due to its complex landform types and special geographic location5,6. The complex and varied topography of the region is a product of strong plate movements and geotectonic activities, mapping rich dynamic information on the uplift and evolution of the plateau. Moreover, the Tibetan Plateau, known as the “Water Tower of Asia”, is an essential birthplace of water resources in China, and the spatial distribution of its landform has an important impact on infrastructure construction and protection, water resource security, and ecosystem changes, etc7,8,9. Accordingly, landform classification research for this region is on the rise.

Current landform classification methods can be broadly categorized into pixel-based approaches and object-based approaches10. Pixel-based methods classify landforms at the level of individual grid cells using spectral features and topographic variables. Common techniques include threshold-based rules, supervised and unsupervised classification, clustering analysis, and machine learning algorithms11,12,13,14. However, these approaches often neglect spatial context and overall morphological patterns, resulting in fragmented or noisy outputs15. Object-based methods group pixels into meaningful landform units through image segmentation or terrain partitioning, and then perform classification at the object level16. Techniques include segmentation–merging strategies17, rule-based or knowledge-driven classification18, as well as recent applications of deep learning and knowledge-graph approaches19,20. Compared with pixel-based methods, object-based approaches take spatial context and morphological structures into account, producing results that are more consistent with the semantic understanding of landforms21. Nevertheless, they are often more complex and require careful parameterization and prior knowledge. To summarize, pixel-based methods emphasize local features and are well-suited for rapid, large-area classification, while object-based methods highlight spatial organization and semantic meaning, thereby providing more realistic representations of geomorphological structures.

Concentrating on the Tibetan Plateau, landform classification can be summarized into two main categories: region-oriented comprehensive landform classification and thematic map-oriented sectoral landform classification studies. In region-oriented landform classification studies, Lin et al.22, Xiao et al.23, and Xu et al.24 have classified landform morphology across the Tibetan Plateau. For thematic landform classification studies, scholars have focused on deciphering and analyzing single landform types or landform objects such as aeolian landforms25, periglacial landforms26, and glaciers27. These studies have explained the spatial distribution of landforms on the Tibetan Plateau to some extent. However, no effective consensus has been reached on the classification system and classification methods for landforms on the Tibetan Plateau. Especially for the complex landform unit of the Tibetan Plateau, the results of the existing landform classification make it difficult to reveal the macroscopic features of the landform effectively, and the data accuracy can hardly meet the needs of detailed landform research. Besides, the existing landform classification methods produce a lot of fragmented units when applied to high-precision DEMs, making it challenging to ensure the integrity of the landform objects. Hence, there is an urgent need to innovate landform classification methods further to realize high-precision classification in the complex landform region of the Tibetan Plateau.

On this basis, this paper takes the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau as the study area, and the research objectives include (1) constructing a new method of landform classification based on the DEM and completing the division of landform types under the premise of considering the global topographic features and the integrity of the landform objects; (2) analyze and quantify the variability in the spatial distribution of landform types in the study area. This study aims to deepen the knowledge of macro-geomorphic patterns and spatial differences in the complex landform area of the Tibetan Plateau and to enrich the theories and methods of geomorphic classification-related studies and digital terrain analysis.

Study area and data sources

Study area

The Tibetan Plateau is the highest globally known as the “third pole”28. In this study, the Tibetan Plateau boundary data compiled by Zhang et al. were utilized to define the extent of the study area, which is the latest and most accurate Tibetan Plateau boundary data available29. According to this extent, the total area of the Tibetan Plateau is 3.0 × 106 km2, geographically located between 25°59′30″N and 40°1′0″N, 67°40′37″E and 104°40′57″E (Fig. 1), and covers nine countries, including China, India, and Pakistan30. The global topography is characterized by high elevations in the northwest and low elevations in the southeast. Mountain ranges with different orientations intersect, dividing the Tibetan Plateau into numerous basins, broad valleys, and lakes, thereby forming a complex and varied plateau landscape31.

Source: generated by the author of this work using ArcGIS Pro 3.5 (https://pro.arcgis.com).

Location map of the study area.

Data sources

-

1.

DEM data.

The digital elevation model (DEM) is one of the key data sets for landform classification. In this study, the FABDEM (Forest and buildings removed Copernicus DEM) with a horizontal resolution of 30 m is employed, which is a secondary deep processing of the Copernicus DEM (Copernicus GLO-30 DEM) and utilizes the machine learning technique of a random forest regression model to remove the height bias of buildings and trees from the Copernicus DEM. The processed FABDEM dataset reduces the average absolute vertical error from 1.61 to 1.12 m in the built-up area and from 5.15 to 2.88 m in the forested area, providing the most recent and best-quality open-source DEM data available32,33,34.

-

2.

Landform map materials.

The landform maps produced by previous researchers are essential references and validation materials for this paper. Currently, there are several sets of landform atlases of the Tibetan Plateau based on different scales and classification systems, among which the Geomorphological Atlas of the People’s Republic of China (1:1,000,000) by Zhou et al. has the highest recognition and popularity35. The dataset is completed through remote sensing interpretation and GIS library building methods based on TM/ETM + image data from Landsat remote sensing satellites, a DEM, 1:250,000 base map, geological maps, historical geomorphological mapping information, and other data. The dataset has been widely used and generally recognized as authoritative since its release. Therefore, the classification criteria and validation of the results in this paper are based on this dataset.

Methods

Segmentation of mountains and plains based on slope-cost distance

In landform classification, plains and mountains provide the basic combination of land surface slope patterns, representing the two most fundamental macroforms of land surface morphology, and the effective division of these two is the basis of landform classification. Plain represents a fundamental geomorphic concept with particular significance in terrestrial landscapes. Despite its widespread usage, the term lacks a rigorous scientific definition and is understood differently across studies. Following the definition in the Dictionary of Geomorphology: an extensive land surface with gentle relief, lower in elevation than plateaus and less undulating than hills36. This study employs a broad notion of plain, including various genetic types (e.g., fluvial, aeolian) as well as gently sloping landforms such as alluvial fans and terraces. After excluding plain from the entire region, the residual areas are delineated as mountains. Cost distance is the calculation of the minimum cumulative cost distance from each image pixel on the element source (element raster) to the cost surface. It is typically used to create the minimum cost path between the source and the target37,38. The cost distance method has also been employed in the extraction of certain landform features, such as dunes39, catchments40, karst landforms41, and loess landforms42. The principle of plains and mountains segmentation based on cost distance is that in areas with small slope values, the cumulative value of slope cost distance increases slowly. When the image pixel moves to the foothill line area, the slope value increases significantly, and the cumulative slope distance rises abruptly. The flow of the cost distance algorithm is shown in Fig. 2.

For the slope cost distance constructed in this paper, the value of the image pixel on the slope cost distance raster reflects the value of the slope depletion when moving from a specific image pixel (source image pixel). This study utilizes the streamflow network extracted from DEM-based hydrological analysis as the input source and the slope layer as the cost raster within the ArcGIS Pro platform. The constructed slope cost distance surface reflects the cost of slope depletion required to reach a specific raster pixel from the source image element. Larger cost values indicate greater cumulative slope values. In practical implementation, the extraction of the streamflow network was conducted in ArcGIS Pro through the sequence of “Fill–Flow Direction–Flow Accumulation” operations to generate a flow accumulation layer. Subsequently, a suitable threshold was applied to the flow accumulation layer using the ‘Raster Calculator’ to delineate the river network. The choice of threshold influences the density of the extracted river network and introduces a certain level of uncertainty. In this study, the threshold of flow accumulation was determined to be 8,000 after iterative adjustments combined with visual inspection. Additionally, it was necessary to determine an appropriate slope cost depletion threshold where the image elements must start from the source image elements and accumulate along the rasters with smaller slopes until that threshold is reached. Since the terrain is flatter where the slope value is lower, these areas formed are the extent of the plains.

Calculation method of mountain relief index using the mountain unit object

Mountain units are the direct object of classification when classifying mountains and are physical units of geography that actually exist. Referring to the watershed segmentation concept, if the DEM is inverted to obtain an inverse DEM, the hydrological characteristics of the inverse terrain are opposite to those of the original terrain43. The watershed boundary line extracted from the inverse terrain, which corresponds to the sink line of the original terrain, divides the inverse terrain into a closed area without water inflow or outflow. This area corresponds to the hilltop control area of the original terrain, thus realizing the natural dissection of the terrain. The dissected independent surface object is the mountain unit, and the entire process is shown in Fig. 3.

Mountain relief is defined as the difference between the elevation of each raster pixel within a given mountain unit and the minimum elevation value for that mountain unit. Since the segmentation of the mountain unit under the constraint of the river network ensures that the starting point of a single mountain unit is located on an intermountain valley, the lowest value of the elevation within the mountain unit can be regarded as the starting point of the mountain uplift, i.e., the datum for the development of the mountain. Under this calculation method, the value of the uplift at any point on the mountain reflects the difference in elevation relative to the base of the mountain44, reflecting the actual vertical change in the height of the mountain, which is more consistent with human perceptions than absolute elevation and topographic relief (Fig. 4).

The formula for calculating the mountain relief is as follows:

Where MUIp is the value of mountain relief at point p, Pele is the value of absolute elevation at point p, and Qele is the value of absolute elevation at the calculated point within the mountain unit, i.e., the minimum elevation value within that mountain unit.

Criteria for landform classification

The classification criteria and nomination of landform types in this paper are consistent with the “Geomorphological Atlas of the People’s Republic of China (1:1000000)” by Zhou et al.45. According to altitude, the landforms are first divided into a six-level system: plains, hills, low mountains, middle mountains, high mountains, and the highest mountains. Secondly, this system is further subdivided according to mountain relief, thus constituting 22 secondary landform types on the Tibetan Plateau. The specific landform types and classification criteria are provided in Table 1.

Results

Spatial distribution pattern of plains and mountains in the study area

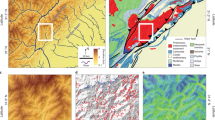

Plains and mountains are the main control structures of the landform system. Based on the slope cost distance method proposed in this study, effective classification of plains and mountains is realized by setting a slope cost distance threshold, and the results are shown in Fig. 5.

The extracted plains of the proposed method were compared with those delineated in the ‘Geomorphological Atlas of the People’s Republic of China (1:1,000,000)’ and further verified using remote sensing imagery. Since the Atlas only provides landform classification results for China, the comparison was limited to the Chinese part of the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 6). The results indicate that the plains extracted in this study cover a broader extent and provide a more detailed representation. The proposed method is also effective in extracting river valley plains in mountainous areas, and even narrow river valley plains in steep canyons can be accurately extracted. The area statistics show that the area of plains is 739,438 km2, accounting for nearly 25% of the total study area; the area of mountains is 2,264,800 km2, accounting for 75%; and the ratio of mountains to plains in the Tibetan Plateau is about 3:1, with mountains occupying an absolutely dominant position.

Source: generated by the author of this work using ArcGIS Pro 3.5 (https://pro.arcgis.com).

Classification results and localized map of the plains.

Segmentation results of mountain units in the study area

The river network in the study area was extracted through hydrological analysis, and then the mountain unit division was constrained based on spatial topological relationships. This operation was executed in the ArcGIS platform. Finally, the results and local effects of mountain unit delineation in the Tibetan Plateau under the constraint of the river network are shown in Fig. 7.

The Tibetan Plateau region was finally divided into 178,286 mountain units, and the four indices of elevation, area, slope, and maximum height difference within the mountain units were measured. The results are shown in Fig. 8.

The sizes of the segmented mountain units ranged from 0.5 to 225.2 km2, with a mean value of 12.7 km2. As for the average elevation, due to its location on the highest plateau in the world, the average elevation value of the mountain unit is relatively high, with an overall average elevation of 4,346 m. The existence of a certain number of low hills leads to an average elevation value of no more than 2,000 m in some of the mountain units. The mountain unit has significantly higher average slope values, with an overall average of 15.5°. Certain differences exist in the range of elevation within the mountain unit, with elevation differences ranging from 0 to 5,135 m and an average of 728 m, which indirectly reflects the steep morphology of the mountains within the Tibetan Plateau.

Landform classification results based on mountain relief and elevation

Based on the mountain relief calculation results, the mountains in the Tibetan Plateau are categorized into five types: hills, low-relief mountains, middle-relief mountains, high-relief mountains, and highest-relief mountains. Their spatial distribution is shown in Fig. 9, and the statistical information is presented in Table 2.

Source: generated by the author of this work using ArcGIS Pro 3.5 (https://pro.arcgis.com).

Classification results of primary landform types in the study area.

The mountains of the Tibetan Plateau are dominated by the low-relief mountains (28%) and middle-relief mountains (27%), whereas the highest-relief mountains are small in size (1%) and show little difference between the areas of the other types of mountains. Significant variability was observed in the average relief, which reached 2108 m in the highest-relief mountain, far exceeding the high-relief (1190 m) and middle-relief mountains (646 m), and relatively small differences in relief between the hills (303 m) and low-relief mountains (110 m). In terms of spatial distribution, hills and low-relief mountains are fragmented and sporadically embedded, with a more concentrated distribution on the northern Tibetan plateau in the center. Middle-relief and high-relief mountains are distributed along the periphery of the study area in a circular pattern. The concentrated areas include the Karakoram Mountains in the northwest and the vicinity of the Hengduan Mountains in the southeast. In contrast, the highest relief mountains are concentrated in the southeast of the study area, and their spatial distribution is relatively sporadic due to the tiny area.

Mountain relief describes the steepness of a mountain; another topographic characteristic of mountains is height or elevation. According to the classification criteria for landform types, elevation is classified into levels and then spatially superimposed with the results of the mountain relief classification, thus obtaining the results of the second-level classification under the two indicators of elevation and mountain relief (Fig. 10).

Source: generated by the author of this work using ArcGIS Pro 3.5 (https://pro.arcgis.com).

Classification results of secondary landform types in the study area.

According to the statistical results of the secondary mountain classification on the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 10), the study area is dominated by the three types of low-relief mountains (18%), middle-relief mountains (15%), and high-relief mountains (14%), which account for 47% of the total area of the mountain regions. Other mountain types show greater variability in spatial distribution.

Discussion

Uncertainty analysis of landform classification results

Uncertainty is one of the inherent properties of geography46,47. Because the main data source for landform classification is a DEM, its resolution directly affects the accuracy of the classification results48. The advantage of a high-resolution DEM lies in the ability to provide more topographic information, accurately reflecting small topographic changes, suitable for recognizing small-scale geomorphic features, and especially better performance in complex terrain. Yet, a high-resolution DEM has a large data load, longer computation and processing times, and high hardware requirements49. The advantage of a low-resolution DEM includes the ability to intuitively reflect the global topographic change characteristics and spatial differentiation laws in a large region, as well as the small data load, small processing workload, and ease of realization. However, the surface information expressed by a low-resolution DEM is coarse, making it easy to confuse similar landforms, resulting in insufficient analytical accuracy.

Regarding the Tibetan Plateau region, scholars tend to use 90-m resolution DEMs for landform classification, while some scholars use 1 km resolution DEMs. For example, Drăguţ and his colleagues produced a 1 km resolution global landform classification dataset based on an object-oriented approach50,51; Iwahashi et al. produced a global landform dataset using the MERIT DEM (Multi-error-removed improved-terrain DEM) resampling to 280-m resolution52. Some scholars also use 30-m resolution DEMs to classify and extract local areas and special landforms, such as landslides53,54, dunes25,55, and glaciers56,57. Considering data applicability, 1-km resolution DEMs are too coarse to obtain high-precision landform classification results. Thus, this study compares the results of landform classification at two resolutions: 30 m and 90 m. It is observed that in the experiment of local landform classification, the 30-m resolution can better distinguish between plain and mountain areas. The extracted plain has a wider range, including the intermountain valley plain, with some plains located near mountain summits (Fig. 11a). According to the definition of plain, relatively flat terrain near mountain summits should also be classified as a plain. In contrast, the plains extracted using the 90-m resolution DEM have a more limited extent (Fig. 11b), with part of the plain misclassified as hills. The recognition effect of different resolution DEMs on individual mountains also varies significantly. The 30-m resolution DEM shows finer recognition of mountain contours (Fig. 11c) and more complex shapes of mountain patches, and the low-elevation hilly areas in the northeast corner can also be recognized. However, in the 90-m resolution DEM, the mountain patch boundaries are simplified, and the patches are more extensive. The low-elevation hilly area in the northeast corner is not identified. The classification refinement is coarse (Fig. 11d). Upon comprehensive comparison, the landform classification results based on the 30-m resolution DEM are more refined, providing more accurate landform boundaries and revealing richer spatial pattern laws and knowledge of the landforms on the Tibetan Plateau.

Limitations and future directions

This paper proposes an innovative automated method and technical framework for the classification of basic landform types, featuring strong generalizability and applicability at the global scale. The proposed approach can provide methodological support for related geomorphological studies. Furthermore, this study produced a 30-m resolution dataset of basic landform classifications for the Tibetan Plateau, effectively enhancing and supplementing the current data resources in this region. This dataset serves as a valuable reference for geological surveys, land resource investigations, landform evolution studies, and related research.

Although this method significantly improves upon the fragmented classification results and low automation levels inherent in traditional landform classification approaches, certain shortcomings still remain. Firstly, this study does not separately classify tablelands as a fundamental landform type but instead merges them into the hill category. This decision is based on the fact that, although tablelands have been mentioned as one of the basic landform types in many studies, the classification criteria remain ambiguous, and no authoritative and unified definition has been established. In the ‘Geomorphological Atlas of the People’s Republic of China (1:1,000,000)’45, tablelands are defined as having a relief generally greater than 30 m, while hills are defined as having a relief of less than 200 m. As can be seen, both tablelands and hills fall within the relief interval of 30 to 200 m; however, no explicit threshold distinguishing the two has been provided, making it challenging to separate tablelands from hills. Additionally, this study proposed a slope cost-distance approach as an alternative to the traditional slope-threshold segmentation method. The proposed approach effectively avoids the fragmentation and internal void effects frequently encountered in slope-threshold segmentation. Nevertheless, similar to the slope-threshold method, the slope cost-distance method still requires the specification of a threshold value to separate plains from mountains. In practice, the threshold is determined by iteratively adjusting the slope cost-distance value, while referencing hillshade maps and remote sensing imagery, to ensure that the segmentation boundary closely aligns with mountain margins. Although this visually assisted approach improves the accuracy of classification results, the objectivity and scientific basis of threshold setting still require further discussion. Future research will further explore classification methods specifically for tablelands and develop genetic landform classification approaches and workflows by integrating multi-source data such as remote sensing imagery, geological maps, and hydrological information.

Conclusion

This paper takes the Tibetan Plateau as the study area, and based on multi-source data such as DEMs, remote sensing images, geomorphological maps, and other data, comprehensively utilizes the ideology of object segmentation and classification oriented to geomorphological entities, digital terrain analysis, and other methods, and carries out systematic research on the indices and classification methods of landform classification. The main conclusions of this paper are as follows:

-

(1)

Methods of mountain relief index and slope-cost distance are proposed in this paper to realize the classification of landform types on the Tibetan Plateau. The new landform classification data are generated based on the FABDEM with a 30-m resolution, which significantly improves the quality of landform classification. Meanwhile, compared with the traditional image-element-oriented landform classification, the concept of landform entity-oriented classification improves the fragmentation phenomenon of the classification results and ensures the integrity of the landform classification objects; the calculation of topographic relief based on the mountain relief index avoids the “myopic” effect of the traditional neighborhood analysis, and more realistically reflects the global topographic changes.

-

(2)

Statistical analysis of the landforms of the Tibetan Plateau shows that the proportion of plains within the mountainous Tibetan Plateau has reached 25%, with a ratio of mountains to plains of nearly 3:1. Among the mountain types, low-relief mountains (21.1%) and middle-relief mountains (20.8%) dominate, with the smallest proportion of the highest-relief mountains (0.5%). In secondary landform types, mountains are dominated by high-elevation mountains, including low-relief high-altitude mountains (11.7%), middle-relief high-altitude mountains (11.1%), high-relief high-altitude mountains (10.2%), and high-altitude hills (9.0%), and the average elevation of mountains reaches 4,346 m. Among plain types, high-altitude plains are also dominant (15.5%).

-

(3)

Regarding the spatial distribution characteristics, the plain has a high degree of fragmentation and a low degree of spatial aggregation, and the overall distribution is characterized by an “from inside to outside” dispersion. The spatial distribution of the mountains, the Himalayas, the Kunlun Mountains, the Qilian Mountains, and the Hengduan Mountains, comprises the main “three horizontal and one vertical” elements of the overall topographic skeleton. This distribution pattern indicates that the landforms in the study area show significant interclass variability in spatial distribution and landscape characteristics, confirming the complex and diverse overall landscape pattern of the Tibetan Plateau.

Data availability

The datasets used in this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mayer, L. Some comments on equilibrium concepts and geomorphic systems. Geomorphology 5, 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-555X(92)90009-D (1992).

Summerfield, M. A. Global Geomorphology (Routledge, 2014). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315841182.

Lin, S., Xie, J., Deng, J., Qi, M. & Chen, N. Landform classification based on landform Geospatial structure – a case study on loess plateau of China. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 15, 1125–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2022.2088874 (2022).

Li, S., Xiong, L., Tang, G. & Strobl, J. Deep learning-based approach for landform classification from integrated data sources of digital elevation model and imagery. Geomorphology 354, 107045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107045 (2020).

Dong, G., Yi, C. & Chen, L. An introduction to the physical geography of the Qiangtang plateau: a frontier for future geoscience research on the Tibetan plateau. Phys. Geogr. 31, 475–492. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3646.31.6.475 (2010).

Zhao, Q. et al. Impact of the Eastern Tibetan plateau on the ecological sensitivity of the West Qinling mountains. Sci. Rep. 15, 4970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89136-4 (2025).

Di, Y., Zhang, Y., Zeng, H. & Tang, Z. Effects of changed Asian water tower on Tibetan plateau ecosystem: a review. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. Chin. Version. 34, 1322–1331. https://doi.org/10.16418/j.issn.1000-3045.2019.11.015 (2019).

Suo, X., Yu, Z. & Cao, S. Utilizing water resources from the Tibetan plateau: Benefits, risks, and future research requirements. CATENA 230, 107256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107256 (2023).

He, M. et al. Spatiotemporal variability of terrestrial water storage over the Tibetan plateau from the joint inversion of GNSS and GRACE observations. Sci. Rep. 15, 27168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12635-x (2025).

Wei, H., Xiong, L., Zhao, F., Tang, G. & Lane, S. N. Large-scale Spatial variability in loess landforms and their evolution, Luohe river Basin, Chinese loess plateau. Geomorphology 415, 108407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2022.108407 (2022).

Maxwell, A. E. et al. Exploring the influence of input feature space on CNN-Based geomorphic feature extraction from digital terrain data. Earth Space Sci. 10, 2563. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EA002845 (2023). e2023EA002845.

Syed Abdul Rahman, S. A. F., Maulud, A., Ujang, K. N., Mohd Jaafar, U. W., Pradhan, B. & W. S. & A framework for extracting and characterizing landform structures under buildings using elevation thresholds and K-means algorithm. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 29, 100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kscej.2025.100324 (2025).

Hengl, T. & Rossiter, D. G. Supervised landform classification to enhance and replace photo-interpretation in semi-detailed soil survey. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67, 1810–1822. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2003.1810 (2003).

Young, F. J. & Hammer, R. D. Defining geographic soil bodies by landscape position, soil taxonomy, and cluster analysis. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 64, 989–998. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2000.643989x (2000).

Myint, S. W., Gober, P., Brazel, A., Grossman-Clarke, S. & Weng, Q. Per-pixel vs. object-based classification of urban land cover extraction using high Spatial resolution imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 1145–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2010.12.017 (2011).

Drăguţ, L. & Blaschke, T. Automated classification of landform elements using object-based image analysis. Geomorphology 81, 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.04.013 (2006).

Anders, N. S., Seijmonsbergen, A. C. & Bouten, W. Segmentation optimization and stratified object-based analysis for semi-automated Geomorphological mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 2976–2985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2011.05.007 (2011).

Gu, H. et al. An object-based semantic classification method for high resolution remote sensing imagery using ontology. Remote Sens. 9, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9040329 (2017).

Peña, J. M. et al. Object-based image classification of summer crops with machine learning methods. Remote Sens. 6, 5019–5041. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs6065019 (2014).

Wang, Z. & Chen, J. Image segmentation and knowledge graph based prototype for ground object interpretation on coastal high resolution remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 46, 4167–4192. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2025.2496530 (2025).

Liu, D. & Xia, F. Assessing object-based classification: advantages and limitations. Remote Sens. Lett. 1, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161003743173 (2010).

Lin, S., Wang, X. & Chen, N. Slope unit-based genetic landform mapping on Tibetan plateau- a terrain unit-based framework for large Spatial scale landform classification. CATENA 236, 107757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107757 (2024).

Xiao, W., Xiong, L., Tang, G., Shao, X. & Wang, J. Geomorphological divisions of the Tibet plateau based on topographical feature point groups from DEMs. Ann. GIS. 20, 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475683.2014.942796 (2014).

Xu, Y., Zhu, H., Hu, C., Liu, H. & Cheng, Y. Deep learning of DEM image texture for landform classification in the Shandong area. China Front. Earth Sci. 16, 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11707-021-0884-y (2022).

Dong, M. et al. Distribution patterns and morphological classification of climbing dunes in the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Aeolian Res. 35, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeolia.2018.09.002 (2018).

Yang, Y., Wu, Q. & Jin, H. High-resolution stable isotopic signals of ground ice indicate freeze–thaw history in permafrost on the Northeastern Qinghai–Tibet plateau. Permafr. Periglac. Process. 34, 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.2172 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Spaciotemporal distribution characteristics of glacial lakes and the factors influencing the Southeast Tibetan Plateau from 1993 to 2023. Sci. Rep. 15, 1966. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86546-2 (2025).

Dong, M. et al. Morphological characteristics and dynamic changes of typical climbing dunes on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Geomorphology 440, 108869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2023.108869 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Li, B. & Zheng, D. A discussion on the boundary and area of the Tibetan plateau in China. Geogr. Res. 21, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.11821/yj2002010001 (2002).

Dou, X. et al. Spatio-temporal evolution of glacial lakes in the Tibetan plateau over the past 30 years. Remote Sens. 15, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15020416 (2023).

Liu, Z., Tapponnier, P., Gaudemer, Y. & Ding, L. Quantifying landscape differences across the Tibetan plateau: implications for topographic relief evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 113, F04018. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JF000897 (2008).

Hawker, L. et al. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 024016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac4d4f (2022).

Meadows, M., Jones, S., Reinke, K. & Copernicus, D. E. M. Vertical accuracy assessment of freely available global DEMs (FABDEM, NASADEM, AW3D30 and SRTM) in flood-prone environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth 17, 2308734. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2024.2308734 (2024).

Marsh, C. B., Harder, P. & Pomeroy, J. W. Validation of FABDEM, a global bare-earth elevation model, against UAV-lidar derived elevation in a complex forested mountain catchment. Environ. Res. Commun. 5, 031009. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/acc56d (2023).

Cheng, W. et al. Research and compilation of the geomorphologic atlas of the people’s Republic of China (1:1,000,000). J. Geogr. Sci. 21, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-011-0831-z (2011).

Zhou, C. H. A Dictionary of Geomorphology (China Water Power Press, 2006).

Becker, D., De Andrés-Herrero, M., Willmes, C., Weniger, G. C. & Bareth, G. Investigating the influence of different DEMs on GIS-based cost distance modeling for site catchment analysis of prehistoric sites in Andalusia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 6, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi6020036 (2017).

Sechu, G. L. et al. A Stepwise GIS approach for the delineation of river Valley bottom within drainage basins using a cost distance accumulation analysis. Water 13, 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13060827 (2021).

Ge, M., Li, F., Ma, J., Yu, F. & Cui, L. An automatic method for extracting sand dunes based on slope cost distance from digital elevation models. Adv. Space Res. 75, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2024.09.034 (2025).

Duarte, L., Godinho, S., Gomes, A., Rodrigues, S. & Teodoro, A. C. A GIS open source application for cost distance modelling for site catchment analysis of prehistoric sites. In Proc. SPIE 12734, Earth Resources and Environmental Remote Sensing/GIS Applications XIV 1273412 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2678993.

Cao, H. et al. Karst landform classification considering surface flow characteristics derived from digital elevation models. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 49, 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5715 (2024).

Li, S. et al. A multilevel dataset of landform mapping and geomorphologic descriptors for the loess plateau of China. Sci. Data. 11, 1282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-04027-z (2024).

Xie, M., Esaki, T., Zhou, G. & Mitani, Y. Geographic information systems-based three-dimensional critical slope stability analysis and landslide hazard assessment. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 129, 1109–1118. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241 (2003).

Iwahashi, J. & Yamazaki, D. Global polygons for terrain classification divided into uniform slopes and basins. Prog Earth Planet. Sci. 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-022-00487-2 (2022).

Zhou, C., Cheng, W., Qian, J., Li, B. & Zhang, B. Research on the classification system of digital land geomorphology of 1∶1000000 in China. J. Geo-Inf Sci. 11, 707–724 (2009).

Hanke, M., Paseka, A. & Sprenger, S. Understanding the meaning of uncertainty in geography education: a systematic review. Teach. Teach. 31, 174–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2023.2263375 (2025).

Yan, G. et al. Modeling computer sight based on DEM data to detect terrain breaks caused by gully erosion on the loess Plateau. CATENA 237, 107837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2024.107837 (2024).

MacMillan, R. A., Martin, T. C., Earle, T. J. & McNabb, D. H. Automated analysis and classification of landforms using high-resolution digital elevation data: applications and issues. Can. J. Remote Sens. 29, 592–606. https://doi.org/10.5589/m03-031 (2003).

Vaze, J., Teng, J. & Spencer, G. Impact of DEM accuracy and resolution on topographic indices. Environ. Model. Softw. 25, 1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.03.014 (2010).

Drăguţ, L. & Eisank, C. Automated object-based classification of topography from SRTM data. Geomorphology 141–142, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.12.001 (2012).

Kazemi Garajeh, M. et al. Developing an integrated approach based on geographic object-based image analysis and convolutional neural network for volcanic and glacial landforms mapping. Sci. Rep. 12, 21396. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26026-z (2022).

Iwahashi, J., Kamiya, I., Matsuoka, M. & Yamazaki, D. Global terrain classification using 280 m dems: segmentation, clustering, and reclassification. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-017-0157-2 (2018).

Gong, Y., Yao, A., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Tian, T. Classification and distribution of large-scale high-position landslides in southeastern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 81, 311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-022-10433-6 (2022).

Qin, Y., Zhang, D., Zheng, W., Liu, B. & Gong, Z. Spatial distribution of near-fault landslides along Litang fault zones, Eastern Tibetan plateau. Geomorphology 455, 109189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2024.109189 (2024).

Hu, G. et al. Holocene aeolian activity in the Zoige Basin, Northeastern Tibetan Plateau, China. CATENA 160, 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.10.005 (2018).

Wang, X., Siegert, F., Zhou, A. & Franke, J. Glacier and glacial lake changes and their relationship in the context of climate change, central Tibetan plateau 1972–2010. Glob. Planet. Change. 111, 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2013.09.011 (2013).

Zhu, C. et al. Recognition of palaeo-glacial troughs with cirques on parts of Tibetan plateau using multi-modal datasets with deep learning models. Geomorphology 468, 109499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2024.109499 (2025).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 42401506 and 42407093) and the Key Projects of Natural Science Research Projects in Colleges and Universities of Anhui Province (grant No. 2024AH051396), Science Research Projects of Chuzhou University (grant No. 2024qd06), the Excellent Scientific Research and Innovation Team of Universities in Anhui Province (No. 2023AH010071). Many thanks are also given to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Formal analysis: Hong Wei, Xiaoli Huang, Xi Chen; Investigation: Zhenjun Yan, Xi Chen; Supervision: Xiaoli Huang; Writing—original draft: Hong Wei; Writing—review & editing: Ling Jiang, Cancan Yang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, H., Jiang, L., Huang, X. et al. A new approach for landform classification based on geomorphic entity objects: a case study on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci Rep 15, 41606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25635-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25635-8