Abstract

Flexible thin-film sensors exhibit considerable application potential in the structural health monitoring of bridges under complex traffic scenarios, owing to their capability of rapidly responding to dynamic loads, static loads, and dynamic-static coupled loads. In this study, following the evaporation crystallization method, ZnO/PVA was deposited on the substrate to form a 10-μm-thick film by adjusting the material ratio (m(ZnO):m(PVA) = 4:1) and solution environment (pH = 12). After cutting and packaging, the flexible piezoelectric film sensor was obtained. The sensing characteristics of the ZnO/PVA film sensor under quasi-static, vibratory, and coupled-force loads were analyzed using a dynamic data acquisition system, revealing excellent response feedback in detecting these three stress states. The sensitivity, stability, and response time were 2.34, 0.34, and 12.41 mV/N; 90.6, 94.4, and 92.3%; and 41, 5, and 8 ms, respectively. Temperature-dependent tests (10–60 °C) demonstrated significant signal stability after implementing a curve-fitting compensation algorithm. This temperature correction mechanism addresses the critical challenge of environmental fluctuations in practical bridge monitoring scenarios where static stresses and dynamic vibrations coexist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The sensor materials currently employed for structural health monitoring of large-scale infrastructure, such as bridges, tunnels, and dams, require significant improvement and enhancement1. Existing mainstream detection methods exhibit notable limitations. For instance, strain gauges with piezoresistive properties are capable of measuring structural deformation under quasi-static stress but fail to detect vibration-induced damage caused by dynamic loads2. On the other hand, rigid piezoelectric ceramics, such as lead zirconate titanate3 and quartz4, are effective in monitoring dynamic load variations. However, these rigid sensors are prone to deformation or even damage under quasi-static loads, which alters the charge distribution on their surfaces and ultimately leads to inaccurate monitoring results. Fiber optic sensing technology offers distinct advantages, including high precision, electromagnetic interference resistance, and excellent durability. When integrated with triboluminescent technology, it can further enable wireless, in-situ, distributed (WID), and continuous sensing capabilities5,6,7,8. However, the complex fabrication processes of fiber optic sensing technology and its requirement for sophisticated supporting equipment result in high construction and operational costs during the construction and service life of bridge structures. Large-scale infrastructure often experiences simultaneous quasi-static and dynamic loads, and the structural damage caused by their coupling effect is both significant and challenging to detect using the aforementioned sensor types. The proposed sensor’s multimodal stress sensing positions it as a promising solution for next-generation smart infrastructure systems requiring accurate and reliable health assessment under complex operational conditions. In this study, we developed a ZnO/PVA flexible piezoelectric thin film sensor that demonstrates excellent adaptability for monitoring both quasi-static and dynamic loads9.

Nano-zinc oxide (nano-ZnO) is an important semiconductor material whose performance relies on its specific crystal morphology and uniform crystal arrangement, exhibiting excellent photoelectric, thermoelectric, and piezoelectric properties10,11,12. These characteristics collectively determine the accuracy of ZnO films in sensing multiple load conditions in practical applications. However, as a nanomaterial, ZnO is highly susceptible to agglomeration, forming relatively large particles, which results in unsatisfactory piezoelectric performance under load13. The addition of polymers has been shown to effectively control ZnO’s crystal structure and enhance its piezoelectric properties. For instance, Ponnamma et al. synthesized ZnO/polymer nanocomposites, achieving multiple crystal morphologies, including nanoparticles, nanoflowers, and nanorods14. Similarly, Esthappan et al. prepared ZnO/polypropylene nanocomposites by melt mixing with 0–5 wt% ZnO, significantly improving the mechanical properties, dynamic mechanical performance, and thermal stability of the composites15 Zhu et al. developed cellulose-based ZnO flexible piezoelectric films using a hydrothermal method, demonstrating excellent signal responses to pressure generated by biological movements and outstanding sensitivity16.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), an environmentally friendly dispersant and binder with excellent biocompatibility, is widely used for modifying ZnO. Roy et al. evaluated the dielectric properties of PVA/ZnO nanocomposite films and found that they exhibit lossless behavior above 10⁶ Hz, indicating their potential for microwave applications. This research provides a theoretical basis for utilizing ZnO/PVA film sensors in detecting quasi-dynamic stress/strain signals17. Fernandes et al. synthesized ZnO nanoparticles with an average diameter of 25 nm using the sol-gel method and observed that the roughness of PVA films remained unchanged upon the addition of ZnO18. Loh et al.19 prepared ZnO-PPS/PVA films and demonstrated that these films exhibit comparable dynamic strain sensitivity and piezoelectricity without requiring high-voltage poling or mechanical stretching, unlike PVDF-based films20. Although PVDF films are mainstream in flexible piezoelectric materials, their synthesis process is complex, and their piezoelectric coefficient is relatively low, making them less favorable compared to alternative materials. Collectively, these studies highlight that ZnO/polymer composites21 have established an irreplaceable position among technologically essential materials due to their broad range of applications.

Nevertheless, in engineering practices involving outdoor operations, temperature is a critical factor influencing the accuracy of sensor signal transmission. Ambient temperature exhibits significant variations throughout the year, with winter temperatures dropping below − 10 °C and even reaching − 30 °C or − 40 °C in high-latitude regions. Conversely, summer temperatures often exceed 35 °C, with near-equatorial regions occasionally surpassing 40 °C. Additionally, daily temperature fluctuations can be substantial. Such wide temperature ranges inevitably affect the electrical properties of nano-ZnO films22. Kumar et al. demonstrated that nanocomposite films incorporating zinc oxide nanostructures within a common paper matrix can serve as energy-conversion devices, transforming mechanical and thermal energy into electrical power23. This study represents an early exploration of the thermoelectric response of ZnO flexible films. To develop a ZnO flexible film sensor with high sensitivity, wide-frequency detection, simultaneous quasi-dynamic stress/strain signal monitoring, and perennial real-time operation capabilities, addressing external interferences such as thermal and light effects remains a significant challenge24. In light of this issue, this research investigates the electric response of ZnO/PVA flexible films to mechanical vibrations under varying temperature conditions.

This study aims to develop a ZnO/PVA flexible piezoelectric thin film sensor capable of detecting the structural health of large-scale infrastructure, such as bridges and tunnels, under combined quasi-static and dynamic loading conditions at varying ambient temperatures. First, the ZnO/PVA ultrathin film was synthesized using a volatile crystallization technique, leveraging the high volatility of acetate and ammonium to form flower-shaped ZnO structures. Second, the sensing characteristics of the ZnO/PVA flexible film under quasi-static, vibrational, and superimposed loads were investigated by simulating these loading conditions and monitoring the corresponding electrical response signals. Third, the influence of ambient temperature variations on the sensor’s output signals was corrected to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the ZnO/PVA flexible film sensor.

Experiment details

Raw materials

Zinc acetate (Zn(CH₃COO)₂, mass fraction ≥ 99%) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA-1788) were purchased from Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ammonia (NH₃·H₂O, mass fraction = 25–28%) was obtained from Yantai Sanhe Reagent Co., Ltd. (Yantai, China). The zinc-based substrate used had a thickness of 400 μm, and ultrapure water prepared in the laboratory was utilized for all tests.

Synthesis of ZnO/PVA and film sensor fabrication

The synthesis process of the ZnO/PVA film sensor is illustrated in Fig. 1. First, 1 g of PVA was added to 60 mL of ultrapure water and stirred at 300 rad/min for 4 hours at 50 °C. After standing for 24 hours, a PVA gel was obtained. Second, a Zn2⁺ ion solution was prepared by dissolving 1.83 g of Zn(CH₃COO)₂ in 100 mL of ultrapure water, assisted by ultrasonic dispersion until complete dissolution (KQ2200DB type, Kunshan Ultrasonic Instrument Co., Ltd., China). Third, ammonia was titrated into the Zn(CH₃COO)₂ solution until the turbidity disappeared, resulting in the formation of a Zn(OH)₄2⁻ sol. During the ammonia titration process, the pH value of the solution varied, which played a critical role in controlling the synthesis of ZnO. Fourth, 60 mL of the PVA gel was mixed into the Zn(OH)₄2⁻ sol under ultrasonic dispersion. Fifth, a polished zinc-based substrate was placed in a petri dish (d = 120 mm), and 10 mL of the sol-gel was added. Sixth, the petri dish was heated at 135 °C for 24 hours to obtain the ZnO/PVA layer.

Subsequently, the material was encapsulated into a flexible film sensor. An electrode made of aluminum foil was attached to the surface25,26, and wires were connected. The working area of the sensor measured 40 mm in length and 10 mm in width, with the layer having a thickness of approximately 10 μm (Based on SEM). Figure 2 shows the microtopography of the ZnO/PVA composite film. After being peeled off from the zinc-based substrate, the ZnO/PVA crystals were attached to the surface of the sample stage via the method of “conductive adhesive fixation + slight compaction”, which allows observation of the growth status of the ZnO/PVA film from multiple angles. By measuring the thickness of two independent ZnO/PVA films in Fig. 2, the average thickness was calculated to be 10.06 μm.

Characterizations of ZnO/PVA layers

The crystal structures, chemical changes, and microstructure of the ZnO/PVA film were characterized using powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 Advance type, Bruker Ltd., Germany), thermogravimetric analysis/differential thermal analysis (TG/DTA, TAQ600, TA Instruments, Newcastle, Delaware), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S3500N type, Hitachi Corp., Japan). The XRD analysis was performed at a scanning rate of 0.25 °/s, with a 2θ range of 5° to 70° and a Cu Kα radiation wavelength of 0.1506 nm. The TG/DTA measurements were conducted from 25 °C to 1000 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen (N₂) atmosphere.

Characterizations of ZnO/PVA film sensors

The test method for evaluating the electrical signal response performance of the ZnO/PVA flexible films is illustrated in Fig. 3. A glass plate (30 mm × 100 mm × 600 mm) was fixed to the connecting rod of the base to form a cantilever beam.

Quasi-static stress response test

The ZnO/PVA flexible film was adhered to the top surface of the cantilever beam, and a counterweight block (30 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm) was attached to the sensor. The quasi-static pressure response performance of the ZnO/PVA flexible films was evaluated by applying a specific pressure to the counterweight block and detecting the electrical signals transmitted by the sensor using a dynamic data acquisition system (DASP-v11 type, INV3062, Orient Institute of Noise & Vibration, Beijing, China). The DASP-v11 test system has a sampling frequency range of 0.5–256 Hz, and the sampling frequency was set to 100 Hz for the experiment. This system is equipped with an INV9311-type force hammer, which is used to apply a specific pressure to the sample under test and has a force measurement range of 0–500 N.

Vibratory load response test

When an object is subjected to impact loads, inertial forces are generated, which reflect changes in the inherent properties of the bridge, such as elastic restoring forces and vibration frequencies. In this test, the counterweight block was removed, and the back of the glass plate was continuously struck with a hammer. The electrical signals transmitted by the sensor were monitored using the DASP-v11 system.

Coupled force response testing

Coupled forces are generated when an object is subjected to both dynamic and static loads, reflecting changes in the properties of the bridge under traffic loads. In this experiment, the counterweight block was attached to the thin-film sensor, and the back of the glass plate was continuously struck with a hammer. The electrical signals transmitted by the sensor were monitored to evaluate its response.

Temperature response test

The experimental setup shown in Fig. 3a was placed inside an electrothermal chamber. The temperature was sequentially calibrated to 22 °C, 30 °C, 38 °C, 46 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, with each temperature maintained for 60 minutes. Following the experimental protocol for the vibratory load response test, the sensing performance of the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor was evaluated under these temperature conditions to comprehensively assess its performance characteristics and sensitivity within the specified temperature range.

Results

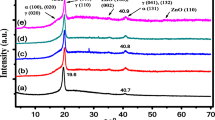

XRD

Figure 4 illustrates the XRD patterns of the ZnO/PVA film at different pH values. Overall, the characteristic peaks of ZnO exhibited an increasing trend as the pH value increased, suggesting an improvement in the crystal structure of ZnO with higher pH values. At pH = 6 and pH = 8, the XRD patterns primarily displayed the characteristic peaks of metallic zinc. When the pH value reached 10, characteristic peaks of both zinc and ZnO were observed simultaneously. However, at pH = 14, the crystallinity of ZnO significantly declined. At pH = 12, the characteristic peaks of ZnO crystals closely matched those of standard crystals, as confirmed by the standard PDF cards (JCPDS 65-3411). The hexagonal wurtzite structure planes, including (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (112), and (201), corresponded well to the 2θ values at 31.2°, 35°, 36.3°, 47.5°, 57.5°, 62.5°, 68.4°, and 68.9°, respectively. These results indicate that the synthesized ZnO exhibits the optimal crystal structure at pH = 12.

TG/DTA

Figure 5 presents the thermogravimetric curves of ZnO/PVA powder. The ZnO content in each ZnO/PVA powder sample, as shown in Fig. 5a, was 100%, 90%, 80%, and 60%, respectively. The curve trend in Fig. 5b significantly differed from those in Fig. 5c–e. When heated to 900 °C, the mass loss rate decreased from 99.6% to 98.6%, representing a reduction of less than 1%. The heat flow curve exhibited only one absorption peak below 100 °C, primarily attributed to the evaporation of free water adsorbed on the ZnO surface.

The mass curves in Fig. 5c–e, displayed three distinct weight loss stages: room temperature to 100 °C, 150 °C to 270 °C, and 600 °C to 900 °C. The weight loss below 100 °C was mainly caused by the volatilization and endothermic process of free water. In the second stage, three prominent endothermic peaks were observed at 150 °C, 220 °C, and 270 °C, corresponding to the volatilization and endothermic process of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) combined with water, the melting and endothermic process of PVA, and the dehydroxylation of PVA, respectively. The mass loss rates for the three ZnO/PVA compositions at this stage were 7.16%, 14.87%, and 27.1%, indicating that the mass loss rate increased with higher PVA content. As the temperature further increased to 350 °C, a weak endothermic peak appeared, corresponding to the pyrolysis, cyclization, and carbonization reactions of PVA. The weight loss observed above 700 °C was primarily associated with the chemical reduction of ZnO by carbon, where the carbon originated from PVA. Based on the principle of mass conservation, the mass ratio of ZnO to PVA was consistent with the design values.

SEM

Figure 6 illustrates the microscopic morphology of the ZnO/PVA film sensor at various mass ratios. The particle morphology of pure ZnO exhibited a spear-like shape overall, with lengths ranging from approximately 500 nm to 1200 nm and a width of about 100 nm. However, significant agglomeration was observed. When the mass ratio of PVA to ZnO was 1:9, Fig. 6b clearly revealed multiple petal-like particles. These petals were composed of regularly shaped cylindrical structures joined together, with lengths ranging from 3000 nm to 6000 nm, significantly larger than those of pure ZnO. A small amount of precipitation was also observed on the particle surfaces. At a PVA-to-ZnO mass ratio of 2:8, the cylindrical morphology of ZnO/PVA became even more pronounced, with particle lengths of approximately 2000 nm and a substantial amount of flocculent precipitation on the surfaces. When the mass ratio of PVA to ZnO was 4:6, the particles displayed a unique flake-like morphology, adhering together with a thickness of about 100 nm and a width of around 400 nm. It can be concluded that as the PVA content increased, the length of ZnO/PVA particles initially increased and then decreased. Notably, when the PVA content ranged between 10% and 20%, the particles exhibited a distinct petal-like morphology.

Figure 7 illustrates the detailed morphology of the ZnO/PVA fracture, revealing exposed hexagonal prisms and a complete bond between the ZnO and PVA interfaces. Figure 7a, b depict the ZnO/PVA morphology with PVA contents of 10% and 20%, respectively. In these images, ZnO is located at the center, with a width of approximately 400 nm, while the outer layer consists of PVA with a thickness of about 160 nm. When the PVA content increased to 20%, the width of ZnO decreased to 250 nm, and the thickness of PVA increased to 204 nm. The thickness of PVA plays a critical role in the composite structure. On one hand, PVA envelops the ZnO surface, providing load-bearing capacity and preventing ZnO from scattering, thereby ensuring the stability of the ZnO/PVA thin film sensor. On the other hand, the PVA coating acts as an insulating layer on the surface of ZnO crystals, preventing electron pair annihilation and thereby maintaining the overall potential difference of the film.

Piezoelectric sensing performance of ZnO/PVA composite films under diverse loading conditions

Quasi-static stress response test

Figure 8 illustrates the time-domain waveform diagrams of the hammering force and the corresponding electric voltage of the ZnO/PVA film sensor. The waveform diagram was categorized into hammer-induced loading profiles and response signal patterns of the ZnO/PVA flexible film sensor. A total of 20 cyclic loading processes were involved, where the response signals of the sensor changed accordingly with the pressure intensity of the quasi-static loads. By magnifying the loading process marked by the gray box, it was found that the quasi-static pressure loading process can be mainly divided into three stages. Firstly, in the pressure application stage, the response signal increased with the rise of pressure and then reached a peak, with the peak response signal lagging by approximately 28 ms. After unloading, the response signal decreased as the load reduced, and the elastic deformation of the film gradually recovered. When the load was completely removed, the electrical signal output by the film gradually recovered to its initial baseline.

Figure 9 shows the response characteristics of the thin-film sensor to quasi-static loads, including response time, sensitivity, and linearity. In Fig. 9a, the times corresponding to the peak pressure and the times corresponding to the response signal are almost all distributed on the fitted line (y=x+0.041, R2=1). This indicates that the response hysteresis times of the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor to the pressure load was 41ms (intercept), which aligns with the performance of traditional pressure sensors27,28. By examining the residual scatter plot, it is observed that the deviations of all signal response times from the fitted line are almost less than 5%, with a temporal response accuracy of 95%. This result indicates that the flexible film sensor exhibits high accuracy in response time to quasi-static pressure. In Fig. 9b, The response signal points almost followed the load distribution corresponding to the fitting line (y=2.34x+163.71, R2=0.98, SD=0.22mV/N). The slope of the curve was 2.34 mV/N, the residuals were all less than 5%, demonstrating that the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor exhibits excellent response performance to quasi-static loads. Given that the force-bearing area of the sensor was 4 × 10⁻4 m2, the sensitivity of the thin-film sensor was calculated to be 0.936 mV/kPa.

Vibratory load response test

Figure 10a illustrates the vibration response spectrum of the sample, which was subjected to 34 impacts within 24 seconds. The curve differed from the relatively linear trend observed in the quasi-static stress loading test. Instead, the electrical signals abruptly peaked after impacting the beam and then gradually decreased until reaching equilibrium. The underlying principle is as follows: when the beam was subjected to an impulse load, it experienced the greatest impact, resulting in the strongest electrical signal from the sensor. Subsequently, the beam’s self-vibration attenuated over time, causing the electrical signal to diminish gradually. As shown in Fig. 10b, the electrical signal amplitude decayed to less than 5% of its peak value within 0.1 seconds after each impact. Within 0.2 seconds, the electrical signal of the sensor essentially returned to its initial level. This indicates that the beam’s self-vibration energy was largely dissipated within this timeframe, with minimal residual vibration remaining before the next impact.

As shown in Fig. 11a, the response time of the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor was 5.2 ms, with a temporal response accuracy of 95%. The linear fit in Fig. 11b was represented by the equation y = 0.34x - 4.78, with an R2 value of 0.99. The slope of the curve was 0.34 mV/N, the coefficient of variation was 5.6% (CV=SD/mean), indicating that the sensor exhibited excellent sensing performance for vibrations caused by impact loads.

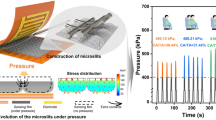

Coupled force response test

Figure 12 presents the signal response spectrum of the flexible thin-film sensor under superimposed loads. Figure 12a illustrates the vibration spectrum under nine impact loads applied within two seconds. The curve trend significantly differed from those observed in the previous two types of loading tests. The electrical signal of the sensor exhibited a wavy decay pattern. This phenomenon occurred because the vibration frequencies of the counterweight block and the cantilever beam differed after the sample was hammered, generating a coupling force. Over time, this force gradually declined, leading to the observed signal decay. Figure 12b displays the specific response of the ZnO/PVA film under coupled loading conditions. From the fitting curve, it is evident that the force generated by vibration exhibited periodic variation characteristics. The fitting equation was y = − 265.6e⁻⁰·⁰⁶⁷ᵗ (t = 1, 2,…, 8), with a frequency of 62.5 Hz, indicating that the attenuation period of the coupling force was 0.016 s. This reflected that the vibration frequency of the small beam is 62.5 Hz. Once the specifications, synthesis process, and applicable conditions of the ZnO/PVA film sensor are confirmed, it can be widely utilized in detecting properties of different materials.

In Fig. 13, the response time, sensitivity and stability of the sensor were 8.41 ms, 12.41 mV/N and 92.3%, respectively. The sensitivity was significantly higher than 2.34 mV/N of quasi-static loading test and 0.34 mV/N of dynamic loading test. The sensitivity under the coupled force was significantly higher than that under the quasi-static and dynamic loads, indicating that the coupling force was substantially greater than the other two types of loading modes.

Moreover, as revealed in Table 1, the sensitivities are basically consistent with the sensor requirements. The Sensitivity of our sensor is 4.96 kPa−1, the sensing range reaches 225 kPa, and the response time is 8.4 ms, which is shorter than that shown for other sensors. The overall results on behaviors indicate that our ZnO /PVA composite film can be a good candidate for attachment to various types of infrastructure for monitoring.

Temperature-dependent piezoelectric sensing characteristics of ZnO/PVA composite films

In this study, considering that the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor is designed for long-term outdoor structural health monitoring, its sensing performance under various temperature conditions was thoroughly investigated.

Figure 14 illustrates the dot plots and fitting curves of the response signals of the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor to vibration loads at different temperatures. The slope of the curves increased continuously with rising temperature, indicating that the electrical signal became more pronounced. The sensitivity values were 0.56 mV/N, 0.78 mV/N, 1.02 mV/N, 1.21 mV/N, and 1.64 mV/N at 22 °C, 30 °C, 38 °C, 46 °C, and 60 °C, respectively. The R-squared values were all greater than 0.95, demonstrating a strong correlation. These results indicate that an increase in temperature enhances the sensitivity of the sensor.

Figure 15 illustrates the dot plots and fitting curves of the response signals of the ZnO/PVA thin-film sensor to coupled loads at different temperatures. Contrary to the trend observed for vibratory loads, the slope of the curves decreased continuously as the temperature increased. The sensitivity values were 9 mV/N, 10.12 mV/N, 13.14 mV/N, 16.11 mV/N, 21.62 mV/N, and 25.42 mV/N at 22 °C, 30 °C, 38 °C, 46 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. The electrical response amplitude of the ZnO/PVA film increased with rising temperature.

The correlation between the sensitivity results and temperature changes was analyzed, and the results are presented in Fig. 16. The sensitivity was significantly influenced by temperature variations, exhibiting a linear relationship as described by the following equations:

The relationship between sensitivity and temperature demonstrated a first-order correlation in the vibratory load test and a third-order correlation in the coupled force test. The trends of the two curves were entirely distinct, primarily due to the fundamentally different loading mechanisms acting on the film sensor. Temperature influences carrier mobility in ZnO crystals: as temperature increases, the thermal activation of charge carriers within the ZnO lattice is enhanced, thereby boosting their migration capability through the crystal structure. This elevated mobility amplifies ZnO’s dynamic piezoelectric response—the efficiency with which mechanical stress (particularly time-varying, dynamic stress) is transduced into electrical signals. Consequently, under vibrational loading, the sensitivity of the ZnO/PVA film sensor’s electrical response exhibited a slight increase with rising temperature, with an increment of 0.03 mV. In contrast to dynamic loading tests, the coupled force condition involves the simultaneous application of quasi-static pressure from the counterweight and dynamic impact from hammering. This synergistic effect is significantly more pronounced than that induced by dynamic loading alone. Meanwhile, temperature variations drive chain relaxation in the PVA matrix: polymer chains acquire thermal energy, which reduces their rigidity and enhances molecular flexibility. Elevated temperatures weaken resistance to static deformation, rendering the matrix more susceptible to shape changes under constant (static) stress. As a result, the increment in the ZnO/PVA film sensor’s response signal tends to level off. Collectively, under the coupled action of quasi-static pressure loading and impact loading, the sensing signal demonstrates a trend of initial rapid growth followed by slow growth with increasing temperature. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating temperature effects into the electrical performance analysis of ZnO/PVA films. Correcting for temperature-induced variations in sensor sensitivity will enhance the robustness and significance of research on ZnO-based sensors.

Conclusions

This study successfully synthesized ZnO/PVA composite crystals via evaporation crystallization, with systematic optimization of synthesis parameters characterized by XRD, thermogravimetric analysis, and SEM.

-

(1)

ZnO-to-PVA mass ratio 4:1 and pH 12 were optimal synthesis conditions, yielding flower-like monomers with superior crystallinity and uniform PVA encapsulation. These microstructures were subsequently deposited onto flexible substrates to fabricate ultrathin films (10 µm thickness) with tailored piezoresistive properties.

-

(2)

The ZnO/PVA film exhibited excellent mechanical response under three types loads. The sensitivity, stability, and response time were 2.34, 0.34, and 12.41 mV/N; 90.6, 94.4, and 92.3%; and 41, 5.2, and 8.4 ms, respectively.

-

(3)

By correcting the temperature’s effect on sensitivity, the accuracy of the sensor could effectively improve. These results highlight the ZnO/PVA film’s potential for advanced applications in flexible pressure sensors, structural health monitoring systems high precision under dynamic-thermomechanical conditions.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Bertola, N. J., Henriques, G. & Brühwiler, E. Assessment of the information gain of several monitoring techniques for bridge structural examination. J. Civ. Struct. Heal. Monit. 13, 983–1001 (2023).

Shohag, M. A. S., Eze, V. O., Braga Carani, L. & Okoli, O. I. Fully integrated mechanoluminescent devices with nanometer-thick perovskite film as self-powered flexible sensor for dynamic pressure sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 6749–6756 (2020).

Zhang, L., Wang, C., Huo, L. & Song, G. Health monitoring of cuplok scaffold joint connection using piezoceramic transducers and time reversal method. Smart Mater. Struct. 25, 035010 (2016).

Kanazawa, K. & Cho, N.-J. Quartz crystal microbalance as a sensor to characterize macromolecular assembly dynamics. J. Sens. 2009, 824947 (2009).

Olawale, D. O. et al. Getting light through cementitious composites with in situ triboluminescent damage sensor. Struct. Health Monit. 13, 177–189 (2014).

Olawale, D. O. et al. Real time failure detection in unreinforced cementitious composites with triboluminescent sensor. J. Lumin. 147, 235–241 (2014).

Olawale, D. O. et al. Development of a triboluminescence-based sensor system for concrete structures. Struct. Health Monit. 11, 139–147 (2012).

Shohag, M. A. S. et al. Development of friction-induced triboluminescent sensor for load monitoring. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 29, 883–895 (2018).

Abdeltwab, E. & Atta, A. Structural and electrical properties of irradiated flexible ZnO/PVA nanocomposite films. Surf. Innov. 10, 289–297 (2021).

Goel, S. & Kumar, B. A review on piezo-/ferro-electric properties of morphologically diverse ZnO nanostructures. J. Alloy. Compd. 816, 152491 (2020).

Le, A. T., Ahmadipour, M. & Pung, S.-Y. A review on ZnO-based piezoelectric nanogenerators: Synthesis, characterization techniques, performance enhancement and applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 844, 156172 (2020).

Purica, M., Budianu, E. & Rusu, E. ZnO thin films on semiconductor substrate for large area photodetector applications. Thin Solid Films 383, 284–286 (2001).

Wacharawichanant, S., Thongyai, S., Phutthaphan, A. & Eiamsam-ang, C. Effect of particle sizes of zinc oxide on mechanical, thermal and morphological properties of polyoxymethylene/zinc oxide nanocomposites. Polym. Testing 27, 971–976 (2008).

Ponnamma, D. et al. Synthesis, optimization and applications of ZnO/polymer nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 98, 1210–1240 (2019).

Esthappan, S. K., Nair, A. B. & Joseph, R. Effect of crystallite size of zinc oxide on the mechanical, thermal and flow properties of polypropylene/zinc oxide nanocomposites. Compos. B Eng. 69, 145–153 (2015).

Zhu, Q. et al. Large enhancement on performance of flexible cellulose-based piezoelectric composite film by welding CNF and MXene via growing ZnO to construct a “brick-rebar-mortar” structure. Adv. Func. Mater. 34, 2408588 (2024).

Roy, A. S., Gupta, S., Sindhu, S., Parveen, A. & Ramamurthy, P. C. Dielectric properties of novel PVA/ZnO hybrid nanocomposite films. Compos. B Eng. 47, 314–319 (2013).

Fernandes, D. et al. Preparation, characterization, and photoluminescence study of PVA/ZnO nanocomposite films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 128, 371–376 (2011).

Loh, K. J. & Chang, D. Zinc oxide nanoparticle-polymeric thin films for dynamic strain sensing. J. Mater. Sci. 46, 228–237 (2011).

Gullapalli, H. et al. Flexible piezoelectric ZnO–paper nanocomposite strain sensor. Small 6, 1641–1646 (2010).

Abdelrazek, E., Elashmawi, I., El-Khodary, A. & Yassin, A. Structural, optical, thermal and electrical studies on PVA/PVP blends filled with lithium bromide. Curr. Appl. Phys. 10, 607–613 (2010).

Sebald, G., Lefeuvre, E. & Guyomar, D. Pyroelectric energy conversion: Optimization principles. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 55, 538–551 (2008).

Kumar, A. et al. Flexible ZnO–cellulose nanocomposite for multisource energy conversion. Small 7, 2173–2178 (2011).

Lu, S.-H., Dai, Y.-T. & Yen, C.-J. The effects of measurement site and ambient temperature on body temperature values in healthy older adults: A cross-sectional comparative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 1415–1422 (2009).

Nour, E. S., Sandberg, M., Willander, M. & Nur, O. Handwriting enabled harvested piezoelectric power using ZnO nanowires/polymer composite on paper substrate. Nano Energy 9, 221–228 (2014).

Wang, X. Piezoelectric nanogenerators—Harvesting ambient mechanical energy at the nanometer scale. Nano Energy 1, 13–24 (2012).

Cui, X. et al. Flexible pressure sensors via engineering microstructures for wearable human-machine interaction and health monitoring applications. Iscience 25 (2022).

Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, M., Dai, F. & Li, Z. Flat silk cocoon pressure sensor based on a sea urchin-like microstructure for intelligent sensing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 17252–17260 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Fabrication and piezoresistive/piezoelectric sensing characteristics of carbon nanotube/PVA/nano-ZnO flexible composite. Sci. Rep. 10, 8895 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Flexible and highly sensitive pressure sensors with surface discrete microdomes made from self-assembled polymer microspheres array. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 221, 2000073 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Flexible, robust, and durable aramid fiber/CNT composite paper as a multifunctional sensor for wearable applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 5486–5497 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. Flexible piezoresistive three-dimensional force sensor based on interlocked structures. Sens. Actuators A 330, 112857 (2021).

Han, Z. et al. Ultralow-cost, highly sensitive, and flexible pressure sensors based on carbon black and airlaid paper for wearable electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 33370–33379 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by Science and Technology Plan of the Department of Transport of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2025B18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuaichao Chen, Jiajing Li, and Wentao Rong conceived and designed the experiments. Shuaichao Chen and Jiajing Li prepared the preliminary draft. Jiajing Li and Wendong Yang revised the manuscript and participated in discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Li, J., Yang, W. et al. Preparation of ZnO/PVA flexible piezoelectric films for sensing dynamic-static superimposed loads under varying temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 42954 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25644-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25644-7