Abstract

This study investigates the ecotoxicological impact of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) on groundwater copepods, which are critical components of aquatic ecosystems. PFOS is recognized as a persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic organic pollutant, yet its effects on copepods and other stygofauna inhabiting groundwater remain largely unexplored. In this study, we assessed the toxicity of PFOS on the copepod Diacyclops humphreysi using standardized protocols outlined in the literature. Copepods were collected from groundwater bores in the Pilbara region of Western Australia and acclimated for two days before being exposed to a range of PFOS concentrations (0–3241 µg/L). Groundwater from the sampling sites was utilised to prepare PFOS solutions, with two replicates for each concentration and 10-20 specimens per replicate. A time-dependent test was conducted to evaluate toxic effects, with copepod mortality recorded until mortality in the control group exceeded 10%. A logistic model was employed to simulate the dose–response relationship, yielding an estimated LC50 of 469.9 ± 117.1 µg/L and LC10 of 142.4 µg/L PFOS at Day 28 for D. humphreysi. This research provides valuable insights into the toxic effects of PFOS on this typical copepod in Western Australia, contributing to the development of groundwater guideline values for the protection of groundwater ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been manufactured and distributed since the early 1960s1. Due to their chemical structure, PFAS exhibit resistance to biodegradation, atmospheric photooxidation, direct photolysis, and hydrolysis, and they are highly soluble in water2,3,4,5. In PFAS, hydrogen atoms on the alkyl chains are fully or partially replaced by fluorine atoms, resulting in strong carbon–fluorine bonds that impart high chemical and thermal stability, as well as significant oxidative resistance. Given their extreme stability, persistence, and potential for bioaccumulation, it is essential to recognize the adverse impacts of PFAS on environmental and human health. Commonly studied compounds frequently detected in the environment include perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), both of which were classified as priority contaminants by the Stockholm Convention in 20016.

Thousands of PFAS compounds can be found in contaminated sites, largely due to the historical use of formulations such as aqueous film-forming foams (AFFF), surfactants, solvents, metal plating, aviation operations, and photography. In addition to contaminating recreational waters and soils through the historical use of firefighting foams, PFAS can also enter these environments via the discharge of sewage and wastewater. Furthermore, PFAS compounds can leach from landfills where products containing these substances are disposed of. The prevalence of PFAS in groundwater surrounding legacy landfills in Australia remains poorly understood7. In a prior study of Australian groundwater, PFOS, PFHxS (perfluorohexanesulfonic acid), PFOA, and PFBS (perfluorobutanesulfonic acid) were detected in all samples, with total PFAS concentrations ranging from 26 ng/L at an ambient background site to 5200 ng/L near a potential industrial point source in Melbourne7.

The detection of PFAS in groundwater has raised significant concerns among environmental managers, the agricultural sector, and regulatory authorities, particularly given the reliance on groundwater for irrigation and, in many cases, for drinking water. In the alluvial-pluvial plain of the Hutuo River in the North China Plain, total PFAS concentrations in groundwater impacted by industrial activities range from 0.56 ng/L to 13.34 ng/L, with PFOA identified as the primary pollutant, averaging at 0.65 ng/L8. Groundwater in Fuxin, China, particularly around the Fuxin Fluorochemical Industrial Park (FIP), is contaminated with PFAS, which may enter locally grown vegetables through irrigation using groundwater sourced from the FIP9. PFBS and PFOA are the most prevalent PFAS in this groundwater, reaching maximum concentrations of 21.2 µg/L and 2.51 µg/L, respectively—both exceeding the updated health advisories for these compounds in drinking water issued by the Minnesota Department of Health and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA)9. Additionally, Szabo et al.10 found that using recycled water for crop irrigation can contribute to PFAS contamination in groundwater. For instance, groundwater samples from Werribee South in Melbourne, Australia, showed total PFAS levels ranging from < 0.03 to 74 ng/L (n = 28), falling within concentrations typically observed in wastewater effluent10. Similarly, PFAS have been frequently detected in Cooper Bayou (averaged 2 ~ 3 ng/g PFAS in sediment11) due to historical uses of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), which can bioaccumulate in fish12.

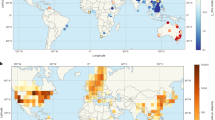

The occurrence of PFOS is frequently detected in groundwater samples. A recent analysis of global distribution of PFAS in groundwater indicates PFOS and PFOA are the most reported PFAS in groundwater13. The weighted mean values were 93,000 (± 27,000) ng/L, 42 (± 24) ng/L and 46 (± 48) ng/L, for PFOS for primary source, secondary source and no-known sources sites, respectively. A highest of PFOS in groundwater was reported in China across Asia region as 844 ng/L among 24 sampling locations14, which was contaminated from a PFAS manufacturing facility.

Among the various PFAS compounds, studying PFOS is crucial due to its persistence, toxicity, potential for bioaccumulation, widespread contamination, regulatory significance, and ecological impacts15,16. Many countries have acknowledged the potential dangers posed by PFOS and have enacted regulations to limit its production and use17,18. PFOS can disrupt aquatic ecosystems by negatively affecting the health of aquatic organisms, including fish and invertebrates. In the United States, a series of Significant New Use Rules (SNUR) were established in 2000, 2002, and 2007 to restrict the production and utilization of materials containing PFOS or its various precursors17. Research on PFOS is essential to inform regulatory decision-making and to assess the effectiveness of these measures. Additionally, understanding its ecological impact on groundwater biota is critical for the conservation of aquatic biodiversity.

Currently, groundwater monitoring and management primarily focus on the quantity and hydrological sustainability of water supplies, alongside concerns about water pollution and quality19. However, there is limited knowledge regarding the potential toxic effects of pollutants on organisms residing in groundwater. The groundwater ecosystem consists of soil, water, and organisms functioning as an integrated environment, with each element closely linked to the others. A comprehensive understanding of the biota and its interactions within the groundwater environment is essential for effective water monitoring and management in the context of ecological risk assessment. While indicators of terrestrial ecotoxicology are well established by regulatory agencies, indicators for groundwater ecotoxicity remain less explored.

Stygofauna, the primary organisms in groundwater ecosystems, should be monitored alongside water quality surveys19. Most stygofauna are crustaceans, although other taxa, such as snails, mites, worms, and fish, are also present20. These organisms, which inhabit subterranean cavities and interstitial spaces within aquifers, play a crucial role in maintaining water quality and transforming nutrients through their grazing, movement, and excretion processes21. Some stygofauna species are particularly sensitive to changes in temperature, energy, nutrient levels, and contaminants, making them suitable as bioindicators22,23,24. Therefore, assessing the toxic effects on stygofauna is critical for understanding the risks faced by these ecosystems.

The water quality criteria for groundwater are currently underdeveloped in many regions, including Australia. It is commonly assumed that the water quality standards established for surface waters will adequately protect groundwater ecosystems and their associated fauna. However, this assumption lacks sufficient validation through rigorous testing. Where testing has occurred, it is clear that surface water fauna cannot be used as reliable indicators for the fauna found in groundwater ecosystems, given their distinct habitat needs and ecological characteristics25. Thus, groundwater ecosystem guidelines are needed and recommended for EU Water Directive considering the uniqueness of groundwater ecosystems26.

The environmental risk assessment for chemicals is normally assessed by comparing the measured environmental concentration (MEC) with the predicted no effect concentration (PNEC) (e.g. European Union, Australia). Unfortunately, the PNEC for groundwater is often derived from the PNEC of surface water species, which differ significantly in morphological, metabolic, and functional traits from groundwater organisms. Specifically, the PNEC is determined based on the No Observed Effect Concentration (NOEC) or the LC10 (Lethal Concentration 10, where 10% of the tested organisms are killed) of the most sensitive taxon, typically chosen from algae, Daphnia, and fish. While this method has demonstrated protective capabilities in many instances, it is unsuitable for groundwater, primarily due to the absence of primary producers and the non-planktonic, sexually reproducing crustaceans found in alluvial aquifers. Furthermore, studies indicate that the metabolic rates of stygobitic copepods are significantly lower than those of their surface-dwelling counterparts27.

Efforts to update these guidelines have stalled due to a dearth of ecotoxicological research on subterranean fauna25,28,29. For instance, Hose25 utilized 48–96 h LC50 data for groundwater-dwelling invertebrate orders such as Crustacea and Rotifera, and compared these to a comprehensive range of surface taxa, including algae, fish, and insects, using species sensitivity distribution (SSD) curves. These curves were developed for various pesticides detected in Australian groundwater and analysed using a Burr Type III distribution model25. The results revealed significant differences in sensitivity to atrazine and chlorpyrifos between surface and groundwater fauna. It is reported that the HC5 values (concentration that can protect 95% species using SSD curve) for groundwater taxa are lower than surface water taxa for 6 out of the 11 pesticides. This underscores the fact that surface water quality guidelines cannot be directly applied to adequately protect or manage groundwater ecosystems25.

Carefully planned experiments are essential for accurately capturing the adverse effects of contaminants, which can vary based on the species of stygofauna being tested, their life stage and life cycle length, exposure concentrations, exposure duration, and chosen test endpoints30,31. Thus, results must be validated with sufficient replicates and multiple species to ensure that the data and resulting predictions are consistent and reliable. This study specifically examines the toxic effects of PFOS on copepods found in groundwater, with future research aimed at investigating other indicator species residing in these ecosystems.

Copepoda, a group of small crustaceans present in nearly all freshwater and saltwater habitats, serve as indicator species for assessing the health of groundwater ecosystems. These small aquatic organisms are often located at the base of groundwater food webs, meaning any changes in their populations can reflect broader ecological impacts. The groundwater copepods are integral to complex food webs that can extend to higher trophic levels, including species consumed by humans. Given their lifespan, which ranges from several months to years32,33, copepods sampled from field sites are suitable for toxicity studies. While the toxic effects of various contaminants, such as propranolol24, As (III), Cr (VI), and Zn34, have been investigated for copepods, there is a notable lack of information regarding PFAS, specifically PFOS.

Due to PFOS potential to biomagnify through food webs, it is crucial to study its effects on copepods as they could serve as vectors of contamination for other organisms, including those in surface waters. Some groundwater copepod species are highly specialized and may even be endemic to specific groundwater systems35,36. Examining their ecotoxicity responses can inform conservation efforts for these unique and often vulnerable species37,38. Evaluating the ecotoxicity of PFOS in groundwater copepods can also guide regulatory decisions regarding permissible levels of PFOS contamination in groundwater, influencing water quality standards.

However, research on the toxicity of PFAS to subterranean fauna remains limited, particularly due to the complexities associated with various PFAS compounds. In this study, we investigated the effects of PFOS on copepods, a sensitive Class commonly found in groundwater systems. Our primary objectives were (1) to determine the mortality of PFOS for groundwater copepods and (2) to derive the toxicity threshold values.

Materials and methods

Copepod sampling

In this study, the copepod Diacyclops humphreysi39 was sampled from threatened ecological community areas in Western Australia, where abundant stygofauna were habituated. The copepod Diacyclops humphreysi were taken with groundwater from five bores at sites in Western Australia, in two rounds of sampling late March-early April 2021 (bores W1, W2, W3 & W4) and March 2023 (Bores W2, W5). The samples were transported through overnight shipping from WA to laboratory in NSW under cooling condition. The toxicity studies were performed using the copepods obtained after acclimatisation for two days (48 h).

Sampling area

The sampling area was located in the Ethel Gorge and Newman area aquifers, one of the most stygofauna-rich habitats recorded in Australia and globally40. Surveys and monitoring were carried out to understand and manage the effects of mining activities in the Ophthalmia floodplain, which hosts the Ethel Gorge aquifer and its groundwater-dependent stygofauna community41. The local species were sampled to assess the toxic effects of PFOS to stygofauna in that region. A license to take fauna for scientific purposes was required under Regulation 17 of the Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 and was obtained by Stantec Inc from the Department of Environment and Conservation.

Sampling method and shipment

Both netting and bailer methods were used for sampling the stygofauna42 to maximize the sample collection. The specialized haul net was designed in accordance with Western Australian EPA guidelines42. The net was used to collect stygofauna residing in the water column and attached to the sides of the bore, while the groundwater bailer was used to collect any stygofauna residing within the sediment at the bottom of the bore43. These methods assume that the water residing within a bore is representative of the faunal communities and chemical properties of water, which is appropriate when discussing water chemistry and stygofauna taxonomic composition44. However, it may not be applicable when assessing the relative abundance of different stygofauna taxa, as abundances are higher within the water column of a bore compared to aquifer water45.

A stainless-steel bailer was lowered to the base of the bore using a stainless-steel cable on a hand reel. The bailer was raised and lowered off the bottom of the bore three times to agitate the sediment, before slowly raising the bailer fully to the surface. The contents of the bailer were collected in a polypropylene bucket and the bailer was rinsed into the same bucket using a spray bottle of bore water. This process was performed three times. The collected water and sediments were then poured through the 150 µm sieve into 2L PFAS free polypropylene sample containers. The specialized haul net was then lowered to the bottom of the bore, raised up and down to agitate the sediment and retrieved slowly in one smooth motion (when possible). Once retrieved, the collection vial was removed, and the contents were gently emptied into a 2L polypropylene sample container containing filtered bore water (filtered through the 150 µm sieve). The net and base were rinsed again with tap water from a wash bottle, and the process was performed three times. Nets with a 50 µm and a 150 µm size were used for sampling (Fig. S1).

The polypropylene containers with stygofauna in bore water were placed in a zip-lock bag and then in an insulated box containing freezer blocks. Several layers of bubble wrap were placed between the freezer blocks and the sample containers to prevent the stygofauna suffering sudden direct heat changes. This cool chain was maintained until they were shipped to the laboratory in Newcastle, NSW, to prevent warming during transport, which would negatively affect the viability of the stygofauna46. The copepods tend to be tolerant to temperature up to around 35 °C for fresh water species, and mortality rates are high at temperatures above 35 °C47. The tolerance to cold conditions is also influenced by the latitude for marine invertebrates with animals from northern populations exhibited lower chill-coma onset temperatures, shorter chill-coma recovery times and faster post-freezing recovery rate48. It is suggested that copepods tend to be unaffected at lower temperatures comparing to higher temperature stress as elevated temperatures can increase metabolism, reduce survival and shorten lifespan49,50,51. It is crucial to maintain cool condition once they are above ground as the ambient temperatures in Western Australia during Feb-April can be well above 35 °C.

Copepod morphology and speciation

The samples were sorted using an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed for morphological identification. Copepods were placed in separate containers filled with groundwater from the respective wells for a 48-h acclimation period prior to toxicity testing. Images were captured to represent the typical morphology of the copepods. For SEM analysis, the copepods were prepared following modified methods from Felgenhauer52 and Huys and Boxshall53. Specifically, the copepods were initially fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for three hours in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The specimens were then rinsed three times for five minutes each in the same buffer, with gentle agitation to remove any residual fixative. Next, the samples were dehydrated in ethanol (EtOH) through a series of concentrations (50%, 75%, 95%, and 100%), with each stage lasting 10 min and involving agitation. Chemical drying was achieved by immersing the samples in mixtures of EtOH and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) for 15 min each in the following ratios: 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2. This was followed by three separate 15-min immersions in HMDS alone. The final HMDS round was allowed to evaporate slowly under nearly closed conditions. Once dried, the samples were mounted on SEM specimen stages, and imaging was conducted using a Zeiss Sigma VP SEM. Copepod speciation was determined through morphological traits as classified by Stygoecologia. The samples intended for speciation identification were preserved in 100% ethanol.

Ecotoxicity testing of PFOS

Bore water was separately filtered through 0.7 µm glass fiber filters prior to being used for toxicity testing to ensure the removal of other animals and potential malicious organisms (e.g., fungi). No food/nutrients were provided during the 48-h acclimatization period in the respective filtered groundwater, followed by the toxicity tests. The copepods were acclimatable separately within the groundwater where they were collected. The use of same groundwater ensured the same groundwater chemistry for copepods. At the end of the acclimatization period, only actively swimming individuals in the filtered groundwater were used for the final tests. A stock solution of PFOS was prepared using Milli-Q water and corresponding filtered bore water by dilution of PFOS stock solution (prepared from 98% PFOS-K, Sigma Aldrich). Eleven nominal concentrations of PFOS in a geometric series were prepared.

Copepods from the five wells (W1-W5) in the proximity of the study area sharing the same aquifer, were used for the toxicity study. The groundwater wells are located in close vicinity and the living conditions in these groundwater habitats are similar. The stygofauna is representative of the aquifer they are coming from and taxonomic compositions are similar for biota inside the groundwater bores and in the adjoining aquifers44. Besides the identification of species for the copepods used in toxicity study could further confirm the minimization of variation from biota.

In total, 320 individual specimens were used for toxicity testing. Individual specimens were placed into 20 mL of PFOS solutions in a polypropylene container, and the study was designed with two replicates, containing 10 individual specimens assigned for each concentration. This was similar approach to the study conducted by Di Lorenzo et al.24 where 20 specimens, individually exposed, were used for each test concentration and the control. For toxicity studies with smaller number of specimens, the tests were repeated and pooled in order to provide sufficient numbers for robust toxicity estimates34. In our study, the individual copepod was retained in the spiked solutions or control solutions prepared from groundwater where the individual copepod was collected. Each vial was closed with a screw cap immediately after specimen loading. The samples were then kept in the dark at 20 ± 0.2 °C. Mortality served as the endpoint to determine the LC10 (concentration that killed 10% of test animals), and LC50 (concentration that killed 50% of test animals). The experiment lasted for 28 days, with observation and mortality counts made on Days 4, 7, 14, 21, 28. Each vial was observed by the naked eye and under a stereomicroscope for the presence of dead animals (specimens showing no movement after gentle shaking of the vial for 15 s) on the above-mentioned observation and counting days. The number of dead animals were recorded and used to calculate LC values. The mortality endpoints were calculated with the toxicity data, where they are deemed valid according to OECD acute toxicity guidelines54, with the mortality in the controls not exceeding 10% for the data used to calculate the toxicity endpoints54. The data from Day 28 was used for the calculation of LC10 and LC50.

Mortality at Day 28 was used for fitting using the Dose Response Function (logistic model) in the OriginLab software (Eq. 1, OriginLab 2018b 9.55, https://www.originlab.com). The logistic model simulates the dose–response relationship between mortality and PFOS concentration and can be used for estimating LC values.

where x is the concentration of PFOS, and y is the mortality of copepods. The four parameters (A1, A2, x0, and p) were determined through model fitting. A1 is the minimum value that can be obtained (i.e., what happens at minimum dose); A2 is the maximum value that can be obtained (i.e., what happens at a maximum dose); When fitting this function, the X values are supposed to be the logarithm of dose. \(x_{0}\) is the point of inflection/center of the curve (i.e., the point on the S-shaped curve halfway between A1 and A2); p is Hill’s slope of the curve (i.e., related to the steepness of the curve at a given point). The EC50 is calculated by:

At the same time, the PFOS concentrations before and after spiking was examined using LC–MS-MS following established method55. The spike in recovery of PFOS ranged from 65.3–110.1% for the samples prepared.

Results and discussion

Groundwater analysis

The geochemical properties of the groundwater samples are summarized in Table 1. Sample temperatures ranged from 27.5 to 30.3 °C, with a mean of 29.2 °C. pH values varied between 7.11 and 7.75, averaging 7.38. Electrical conductivity (EC) ranged from 1174 to 2189 µS/cm, with a mean of 1772 µS/cm, while dissolved oxygen (DO) levels fluctuated between 9% and 29.2%, averaging 18%. The DO value can significantly influence groundwater quality by regulating the oxidation state of trace metals and constraining the bacterial metabolism of dissolved organic compounds56.

Sampling was conducted in March, during which the average temperature in the Pilbara reaches 36 °C. Groundwater temperatures are typically a few degrees lower than ambient air temperatures57. To minimize stress and ensure the survival of copepods during transport, samples were kept at cooler temperatures.

Temperature measurements for the wells were taken at the surface (Table 1, 27.5–30 °C); however, temperatures are generally several degrees cooler at greater depths. The temperature gradually decreases by approximately 4.5 °C at a depth of about 10 m58. Therefore, cooler conditions were maintained during transportation and throughout the toxicity study following a 2-day acclimatization period. No significant mortality was observed upon receipt of the samples or after acclimatization. The specimens used in the toxicity study were kept under the same laboratory conditions, aside from exposure to PFOS, to facilitate comparative analysis of mortality results.

The groundwater was tested for cations and dissolved organic content, with the results presented in Table 2. The analysis revealed the presence of strontium (Sr) in the groundwater samples, while other metal(loid)s was either low or below the detection limit. Consequently, it is unlikely that the metal(loid)s detected in the water samples contribute to the observed toxic effects. The dissolved carbon (< 0.45 µm) is primarily inorganic. Research has demonstrated that vertically migrating zooplankton, such as copepods, can transport significant amounts of dissolved inorganic carbon into deeper water. This occurs as they feed on surface waters and subsequently release the carbon through sinking fecal pellets59,60. Copepods also consume bacteria, detritus, and smaller animals61.

Copepod morphology

Samples used for toxicological testing were analyzed morphologically. Figure 1 presents images of animals collected from locations W1 and W2, captured using an Olympus SZ61 stereomicroscope and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Panels a-d of Fig. 1 highlight the absence of eyes and the pale, translucent bodies of the stygofauna. The SEM images in panel were taken after fixation and dehydration, confirming the presence of appendages and revealing the organisms’ structural details.

Exemplar stygofauna Copepod specimens collected from wells W1 (a, b) and W2 (c), and the copepod nauplii stage obtained from W4 (d); SEM images of copepod specimens from well W2 (e, e1) showing: ventral view of the copepod, (e1) part of the legs, urosomal segments, caudal ramus, lateral caudal seta and terminal caudal setae of, and a dorsal view of the copepod; (e2) part of urosomal segment and caudal ramus of the copepod from well W3.

The term “Copepoda” derives from the Greek words “kope”, meaning “oar”, and “podos”, meaning “foot”, reflecting their distinctive swimming legs32. Copepods reproduce sexually and undergo 12 life stages to reach full maturity. The initial six stages are referred to as “nauplii” (Fig. 1d), while the subsequent five stages are called “copepodids”32. Generally, the body of a copepod is elongated and segmented, protected by an exoskeleton. The first antennae, also known as antennules, serve multiple functions related to feeding, locomotion, and reproduction (Thorp and Covich32). Equipped with both chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors, these antennae help identify prey, mates, predators, and harmful substances such as pollutants. In male copepods, the first antennae are adapted with geniculae, which facilitate mating. The abdomen extends into two caudal rami, which bear various setae and spines, while the anus is located at the posterior end of the urosome, just above the caudal rami. Typically, copepod females are larger than males.

The samples collected predominantly comprised the cyclopoid copepod Diacyclops humphreysi, with a significant presence of nauplii. However, only adult individuals were utilized for the toxicity studies.

Effects of PFOS on mortality of Copepoda

PFAS analysis was conducted on groundwater samples prior to spiking, revealing results below the limit of detection (LOD) of 0.05 µg/L for 28 PFAS components, which included PFCAs, PFSAs, FASAs, and FTSAs across all tested samples. Various concentrations of PFOS, ranging from 0 to 3241 µg PFOS/L, were prepared and analyzed following spiking in the groundwater samples. The mortality rates of copepods exposed to PFOS are presented in Fig. 2. The mortality rates varied among copepods depending on both the concentration of PFOS and the duration of exposure (Fig. 2). In general, increased exposure time correlated with higher mortality rates. According to OECD guidelines, mortality in control samples should not exceed 10% at the conclusion of the test54. As such, the study was deemed valid up to Day 28, where mortality remained below 10% in control samples. No significant differences in mortality rates were observed at concentrations up to 588.8 µg/L after two weeks of exposure; however, mortality rates increased beyond the two-week mark.

By Day 28, mortality rates were recorded at PFOS concentrations of up to 196.4 µg/L, fluctuating between 0 and 25%. However, mortality rates increased to 100% within the PFOS concentration range of 1195 to 2673 µg/L (Fig. 2a). At a concentration of 589 µg/L PFOS, the mortality rate reached nearly 65%, indicating significant toxicity for copepods. The fluctuations in mortality rates at lower concentrations may be attributed to individual variations in copepod responses to lower doses of PFOS. In contrast, when PFOS concentrations exceed a certain threshold (above 589 µg/L), the toxicity levels increase, resulting in higher mortality rates.

Mortality data collected on Day 28 were fitted to a logistic model (Eq. 1, Fig. 2b). The parameters derived from this model are as follows: A1 is 12.1 ± 3.6% (minimum mortality); A2 is 98.0 ± 8.7% (maximum mortality); 10Logx0 is 469.9 ± 117.1 µg/L (point of inflection, indicating the LC50 value); and p is 1.8 ± 0.7 (Hill’s slope of the curve). The model fitting yielded an R2 of 0.90, with a standard error for the EC50 value of 117.1 µg/L. This substantial variation in model fitting may result from the fluctuations in mortality observed at lower PFOS levels. The LC10 value determined from the experiment was calculated to be 142.4 µg/L.

Further investigation into the toxic effects of PFOS on different groups of stygobitic fauna is necessary to establish threshold values. There is a significant gap in the literature regarding the toxicity of PFOS to groundwater fauna, with most relevant studies focusing on surface water organisms. Li63 conducted an acute toxicity study examining PFOS and PFOA on four freshwater species: the freshwater planarian Dugesia japonica, the freshwater snail Physa acuta, the water flea Daphnia magna, and the green neon shrimp Neocaridina denticulata. The 48-h LC50 values for PFOS across all four species ranged from 27 to 233 mg/L, while the 96-h LC50 values for three of the species ranged from 10 to 178 mg/L. In contrast, the cyclopoid copepod D. humphreysi, the focus of the current study, exhibited a considerably higher sensitivity to PFOS, with a 28-day LC50 value of 469.9 ± 117.1 µg/L, indicating prolonged toxic effects. Li63 also emphasized the need for further research on the long-term ecological impacts of PFOS on aquatic fauna to inform ecological risk assessments of PFAS compounds. Among the four model organisms commonly used for freshwater toxicology assays—Chironomus dilutus (midge), Ceriodaphnia dubia (water flea), Hyalella azteca (amphipod), and Danio rerio (zebrafish)—C. dilutus was identified as the most sensitive species, with a 16-day LC50 of 7.5 µg/L, while C. dubia and H. azteca demonstrated greater tolerance. Notably, Hyalella azteca exhibited a 42-day LC50 of 15 mg/L, indicating a tolerance more than 30 times greater to PFOS compared to the copepods studied64. Studies on PFOS toxicity to freshwater copepods is also sparse. Sanderson et al.65,66 and Boudreau et al.67 investigated the toxic effects of PFOS and PFOA to zooplankton mixture including copepods, which showed decreased richness and greatest sensitivity for copepod. Chronic toxicity of PFOS to 11 benthic estuarine/marine species68 indicated no observed toxicity for copepod in exposures with 170–180 mg/kg in spiked-sediments and 0.8–2 mg/L in the overlying waters. However, the toxic effects of four fire suppressor to copepod (Nitocr sp.) indicated a EC50 level ranging from 0.00358% ~ 0.03081%68. In 14-day and full-life chronic PFOS toxicity tests performed on the mayfly (Neocloeon triangulifer), a surface water organism, the lowest 10% effect concentration was found to be 0.272 μg/L of PFOS, with 96-h LC50 values recorded at 82 μg/L. These findings suggest that mayflies are more sensitive to PFOS than the copepod D. humphreysi69.

Boudreau et al.67 conducted toxicity testing on freshwater organisms and reported that the concentration of PFOS required to cause 50% inhibition of growth (IC50) in Daphnia pulicaria was 134 mg/L. Notably, they observed significant adverse effects (p ≤ 0.05) in all organisms tested at concentrations above 134 mg/L. This suggests that copepods are more sensitive to PFOS than previously reported in other studies. Considering the limitations of traditional approaches using surface water fauna for predicting the ecotoxicity of compounds in groundwater ecosystems, further research is needed that incorporates groundwater stygofauna to accurately assess the ecological risks posed by such contaminants.

Comparison with existing toxicity studies for PFOS

The toxicity testing conducted in this study was evaluated according to the ANZECC and ARMCANZ study quality guidelines62, as detailed in Table S1. The overall score was 81.9%, indicating that our study produced high-quality data. The LC10 values for Diacyclops humphreysi exposed to PFOS were found to be 142.4 µg/L, which falls within the range of various guideline values for drinking water, reaction water, surface water, and wastewater levels in Australia and other countries (0.13–700 µg/L), as shown in Table S2.

The default guideline values (DGVs) established in water quality guidelines primarily rely on literature data derived from standardized tests conducted on commonly used test species in generic laboratory conditions70. As per the ANZECC and ARMCANZ62 guidelines, laboratory data have occasionally been utilized to calculate guideline values for physical and chemical stressors71,72,73. Field-effect guideline values can be derived following the methodologies outlined in ANZECC and ARMCANZ62. Additionally, laboratory toxicity data can be employed to establish dose–response curves for the derivation of guideline values, which can be approached through either the species sensitivity distribution (SSD) method or a most sensitive species-based approach. Certain studies have observed that field-based and laboratory-based assessment methods typically yield similar guideline values for salinity71,72,73.

Site-specific water quality guideline values for toxicants and physical and chemical stressors can be estimated using a derivation method74 to develop appropriate DGVs. However, the statistical distribution method is recommended for deriving guideline values for toxicants62, with a focus on laboratory data. It is advisable to use chronic toxicity data from at least five test species—preferably exceeding eight, and ideally more than 15—covering at least four taxonomic groups for the SSD approach74,75. The lack of toxicity testing using groundwater stygofauna were largely related to the challenges for culturing in laboratory conditions and naturally low abundance at field sites. However, sampling species native to groundwater environments provides data directly relevant to the groundwater ecosystem. Due to the endermic nature of stygofauna, the direct toxicity testing would provide realistic estimation of vulnerability and sensitivity of stygofauna to external stressors. The trade-offs are challenges to maintain groundwater conditions and less standardised comparing to that of cultured testing even though the utilisation of field specimen is also gradually standardised with increasing research investigations31. The small populations and slow reproductions extend the research efforts and time required for completing the toxicity testing.

Thus, there is a lack of research on the sensitivity of freshwater copepods to various concentrations of PFOS. However, some studies have investigated the sensitivity of marine copepods to PFOS and other chemicals. For instance, Bouderau et al.76 found that the most sensitive taxonomic groups, Cladocera and Copepoda, were nearly eliminated in treatments of 30 mg PFOS/L after seven days of exposure. This finding is not surprising, as the concentration used in their study was nearly six times higher than the maximum concentration identified in our current research, which yielded an LC50 of 0.47 ± 0.12 mg/L for copepods. Generally, zooplankton demonstrate lower tolerance to PFOS compared to PFOA66.

The calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus is regarded as an ideal organism for toxicity testing in estuarine and marine environments due to its broad tolerance to various environmental parameters, including suspended solids, sedimentation, and salinity77. Kennedy et al.78 conducted a 48-h acute toxicity test using the marine North American copepod Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus, which remains planktonic throughout its lifecycle. The LC50 ± standard deviation for copper (Cu), phenanthrene, and un-ionized ammonia were found to be 32 ± 15 µg/L, 161 ± 51 µg/L, and 1.08 ± 0.30 mg/L, respectively. Notably, this copepod exhibited less sensitivity to un-ionized ammonia compared to other commonly tested marine species78.

The ecotoxicity of perfluorinated acid degradation products was investigated using the amphipod Hyalella Azteca79. The degradation products examined included saturated (FTsCA) and unsaturated (FTuCA) fluorotelomer carboxylic acids with carbon chain lengths of 6:2, 8:2, and 10:2. The study found that H. azteca was most sensitive to the 8:2 FTsCA and 10:2 FTuCA, reporting LC50 values of 5.1 and 3.7 mg/L, respectively79. A related study on PFOA and stygofauna also used H. azteca and was conducted in Ontario, Canada80. The authors found a significant reduction in amphipod survival at 97 mg/L, with a 42-day LC50 of 51 mg/L for PFOA. Additionally, they observed that growth and reproduction were more sensitive endpoints, each with a 42-day EC50 of 2.3 mg/L PFOA80. In comparison, our study reported a 28-day LC50 value of 0.47 ± 0.1 mg/L for PFOS. Given that PFOS is generally more toxic to organisms than PFOA, these LC50 values, although derived from two different stygobitic taxa, are relatively comparable as both belong to groundwater-dwelling organisms.

Another study conducted in Australia by Logeshwaran, Sivaram et al.81 investigated the toxicity of PFOS and PFOA to the water flea Daphnia carinata. Their results indicated that PFOS exhibited greater toxicity than PFOA, with 48-h LC50 values (confidence intervals) for PFOA and PFOS reported at 78.2 (54.9–105) mg/L and 8.8 (6.4–11.6) mg/L, respectively81. In contrast, surface water invertebrates appear to be more tolerant to PFOS compared to the groundwater copepod Diacyclops humphreysi from our study, which showed a 28-day LC50 value of 0.47 ± 0.12 mg/L PFOS.

A compilation of freshwater aquatic chronic toxicity values (EPA final chronic values) for PFOS is presented in Fig. 3, using data from recent Aquatic Life Criteria for PFOS82. The Genus Mean Chronic Values derived from USEPA ranged from 0.00226 to 8.64 mg/L including 17 genus species.

The Genus Mean Chronic Values for freshwater species for PFOS exposure82. The dotted line indicating the LC10 values obtained in this study for groundwater copepods.

The current study on PFOS toxicity endpoints of Diacyclops humphreysi demonstrates a medium sensitivity level comparing with above-ground freshwater biota, which includes invertebrates, amphibians, fish, insects, as outlined in the EPA document (Fig. 3). This suggests that Diacyclops humphreysi may be a medium sensitive species in groundwater. However, it’s important to note that this comparison is not based on biota from similar habitats. Additional toxicity studies involving benthic biota would provide more relevant information. Moreover, further investigation is needed to enhance the derivation of threshold values through additional toxicity testing with a broader range of species.

Similarly, four ranked estuarine/marine genus mean chronic values include Perna (0.0033 mg/L), Austrochiltonia (0.01118 mg/L), Americamysis (0.3708 mg/L), and Tigriopus (0.7071 mg/L). The LC10 values for Diacyclops humphreysi is higher than Austrochiltonia and Perna while lower than Americamysis and Tigriopus. This suggests that marine invertebrates, such as the eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica83, the saltwater mysid Mysidopsis bahia83, and the crustacean Siriella armata84, Tigriopus japonicus85 exhibit comparatively greater tolerance to PFOS than the freshwater invertebrate Diacyclops humphreysi used in our study.

Conclusion

Stygofauna are increasingly recognized as sensitive biological indicators of the health of groundwater ecosystems. However, the toxic effects of various contaminants on the mortality and behaviour of stygofauna remain relatively unknown. This study investigated the ecotoxicological effects of PFOS on copepod samples collected from designated sites. The results demonstrated an increase in mortality with prolonged exposure to PFOS. The findings were based on copepods from mixed wells, which may also contribute to variations in the obtained data.

This is the first study to assess PFOS toxicity on stygofauna sampled from groundwater wells at field sites. The species tested, specifically the cyclopoid copepod Diacyclops humphreysi, exhibited a degree of tolerance to PFOS, with an LC50 value of 469.9 ± 117.1 µg/L and an LC10 value of 142.4 µg/L. However, it is important to note that other stygofauna species may be more sensitive to PFOS compounds.

The findings of this study provide valuable information that will enhance the scientific community’s understanding of the toxic effects of PFOS in subterranean ecosystems. Such knowledge is crucial for risk assessment and the development of remediation strategies for groundwater. This investigation focused on PFOS, a major PFAS of current concern in Australia, using an invertebrate model. Future research should also evaluate the toxicity of other PFAS, e.g. PFHxS and PFOA.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request, which can be obtained through authors [ravi.naidu@newcastle.edu.au], [Yanju.liu@newcastle.edu.au], [Ayanka.Wijayawardena@newcastle.edu.au].

References

Moody, C. A. & Field, J. A. Perfluorinated surfactants and the environmental implications of their use in fire-fighting foams. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34(18), 3864–3870 (2000).

Biswas, B. et al. The fate of chemical pollutants with soil properties and processes in the climate change paradigm—A review. Soil Syst. 2(3), 51 (2018).

Teaf, C. M. et al. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA): Environmental sources, chemistry, toxicology, and potential risks. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 28(3), 258–273 (2019).

Naidu, R. et al. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Current status and research needs. Environ. Technol. Innov. 19, 100915 (2020).

Arias Espana, V. A., Mallavarapu, M. & Naidu, R. Treatment technologies for aqueous perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA): A critical review with an emphasis on field testing. Environ. Technol. Innov. 4, 168–181 (2015).

UNEP, Guidance on Best Available Techniques and Best Environmental Practices for the Use of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), and their Related Compounds Listed Under the Stockholm Convention. Geneva, Switzerland. (2021).

Hepburn, E. et al. Contamination of groundwater with per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from legacy landfills in an urban re-development precinct. Environ. Pollut. 248, 101–113 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Contamination profiles of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in groundwater in the alluvial-pluvial plain of Hutuo river, China. Water 11(11), 2316 (2019).

Bao, J. et al. Perfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater and home-produced vegetables and eggs around a fluorochemical industrial park in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 171, 199–205 (2019).

Szabo, D. et al. Investigating recycled water use as a diffuse source of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) to groundwater in Melbourne Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 1409–1417 (2018).

Wilkinson, R. S. et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids in sediment and water surrounding historical fire training areas at Barksdale air force base. PeerJ 10, e13054 (2022).

Lanza, H. A. et al. Temporal monitoring of perfluorooctane sulfonate accumulation in aquatic biota downstream of historical aqueous film forming foam use areas. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 36(8), 2022–2029 (2017).

Johnson, G. R. et al. Global distributions, source-type dependencies, and concentration ranges of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 841, 156602 (2022).

Tang, Z. W. et al. A review of PFAS research in Asia and occurrence of PFOA and PFOS in groundwater, surface water and coastal water in Asia. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 22, 100947 (2023).

Hayman, N. T. et al. Aquatic toxicity evaluations of PFOS and PFOA for five standard marine endpoints. Chemosphere 273, 129699 (2021).

Pierozan, P., M. Kosnik, and O. Karlsson, High-Content Analysis Shows Synergistic Effects of Low Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOS) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (PFOA) Mixture Concentrations on Human Breast Epithelial Cell Carcinogenesis. Environment International. p. 107746. (2023).

Lindstrom, A. B., Strynar, M. J. & Libelo, E. L. Polyfluorinated compounds: Past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45(19), 7954–7961 (2011).

Löfstedt Gilljam, J. et al. Is ongoing sulfluramid use in South America a significant source of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS)? Production inventories, environmental fate, and local occurrence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50(2), 653–659 (2016).

Tomlinson, M. et al. Deliberate omission or unfortunate oversight: Should stygofaunal surveys be included in routine groundwater monitoring programs?. Hydrogeol. J. 15(7), 1317–1320 (2007).

Glanville, K. et al. Biodiversity and biogeography of groundwater invertebrates in Queensland Australia. Subterr. Biol. 17, 55 (2016).

Hancock, P. J., Boulton, A. J. & Humphreys, W. F. Aquifers and hyporheic zones: towards an ecological understanding of groundwater. Hydrogeol. J. 13(1), 98–111 (2005).

Plénet, S. Metal accumulation by an epigean and a hypogean freshwater amphipod: Considerations for water quality assessment. Water Environ. Res. 71(7), 1298–1309 (1999).

Hose, G. C. et al. The Toxicity and Uptake of As, Cr and Zn in a Stygobitic Syncarid (Syncarida: Bathynellidae). Water 11(12), 2508 (2019).

Di Lorenzo, T. et al. Environmental risk assessment of propranolol in the groundwater bodies of Europe. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113189 (2019).

Hose, G. C. Assessing the need for groundwater quality guidelines for pesticides using the species sensitivity distribution approach. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 11(5), 951–966 (2005).

Di Lorenzo, T. et al. EU needs groundwater ecosystems guidelines. Science 386(6726), 1103–1103 (2024).

Di Lorenzo, T. et al. Metabolic rates of a hypogean and an epigean species of copepod in an alluvial aquifer. Freshw. Biol. 60(2), 426–435 (2015).

Hose, G. C. et al. Down under down under: Austral groundwater life. In Austral ark: The state of wildlife in Australia and New Zealand 512–536 (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Castaño-Sánchez, A., Hose, G. C. & Reboleira, A. S. P. Ecotoxicological effects of anthropogenic stressors in subterranean organisms: A review. Chemosphere 244, 125422 (2020).

Suedel, B., Rodgers, J. Jr. & Deaver, E. Experimental factors that may affect toxicity of cadmium to freshwater organisms. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 33(2), 188–193 (1997).

Di Lorenzo, T. et al. Recommendations for ecotoxicity testing with stygobiotic species in the framework of groundwater environmental risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 681, 292–304 (2019).

Thorp, J. H. & Covich, A. P. Ecology and Classification of North American Freshwater Invertebrates (Academic press, 2009).

Hirche, H.-J. Long-term experiments on lifespan, reproductive activity and timing of reproduction in the Arctic copepod Calanus hyperboreus. Mar. Biol. 160(9), 2469–2481 (2013).

Hose, G. et al. The toxicity of arsenic (III), chromium (VI) and zinc to groundwater copepods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23(18), 18704–18713 (2016).

Iepure, S., Bădăluţă, C.-A. & Moldovan, O. T. An annotated checklist of groundwater Cyclopoida and Harpacticoida (Crustacea, Copepoda) from Romania with notes on their distribution and ecology. Subterr. Biol. 41, 87–108 (2021).

Lopez, M. L. D. & Papa, R. D. S. Diversity and distribution of copepods (Class: Maxillopoda, Subclass: Copepoda) in groundwater habitats across South-East Asia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 71(3), 374–383 (2019).

Ferreira, D. et al. Obligate groundwater fauna of France: Diversity patterns and conservation implications. Biodivers. Conserv. 16, 567–596 (2007).

Karanovic, T. et al. Two new subterranean ameirids (Crustacea: Copepoda: Harpacticoida) expose weaknesses in the conservation of short-range endemics threatened by mining developments in Western Australia. Invertebr. Syst. 27(5), 540–566 (2013).

Pesce, G., De Laurentiis, P. & Humphreys, W. Copepods from ground waters of Western Australia, I. The genera Metacyclops, Mesocyclops, Microcyclops and Apocyclops (Crustacea: Copepoda: Cyclopidae). Rec. West. Aust. Mus. 18, 67–76 (1996).

Halse, S. et al. Pilbara stygofauna: deep groundwater of an arid landscape contains globally significant radiation of biodiversity. Rec. West. Aust. Mus. 78, 443–483 (2014).

McKenzie, N., Van Leeuwen, S. & Pinder, A. Introduction to the Pilbara biodiversity survey, 2002–2007. Rec. West. Aust. Mus. Suppl. 78(1), 3–89 (2009).

EPAWA, Sampling Methods and Survey Considerations for Subterranean Fauna in Western Australia, in Guidance Statement 54a. (2007).

Serov, P. STYGOFAUNA. (2012).

Hahn, H. J. & Matzke, D. A comparison of stygofauna communities inside and outside groundwater bores. Limnologica 35(1–2), 31–44 (2005).

Korbel, K. et al. Wells provide a distorted view of life in the aquifer: implications for sampling, monitoring and assessment of groundwater ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1–13 (2017).

Svensson, C. J., Hyndes, G. A. & Lavery, P. S. An efficient method for collecting large samples of live copepods free from detritus. Mar. Freshw. Res. 61(5), 621–624 (2010).

Jiang, W. et al. Mechanisms of thermal treatment on two dominant copepod species in O3/BAC processing of drinking water. Ecotoxicology 30, 945–953 (2021).

Wallace, G. T., Kim, T. L. & Neufeld, C. J. Interpopulational variation in the cold tolerance of a broadly distributed marine copepod. Conserv. Physiol. 2(1), cou041 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4732475/ (2014).

Sasaki, M. & Dam, H. G. Global patterns in copepod thermal tolerance. J. Plankton Res. 43(4), 598–609 (2021).

Heine, K. B. et al. Copepod respiration increases by 7% per °C increase in temperature: A meta-analysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 4(3), 53–61 (2019).

Saiz, E. et al. Reduction in thermal stress of marine copepods after physiological acclimation. J. Plankton Res. 44(3), 427–442 (2022).

Felgenhauer, B. E. Techniques for preparing crustaceans for scanning electron microscopy. J. Crustac. Biol. 7(1), 71–76 (1987).

Huys, R. & Boxshall, G.A. Copepod Evolution. (1991).

OECD., OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals. 207 Adopted 1984. 1994: Organization for Economic.

Umeh, A. C. et al. A systematic investigation of single solute, binary and ternary PFAS transport in water-saturated soil using batch and 1-dimensional column studies: Focus on mixture effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 461, 132688 (2024).

Rose, S. & Long, A. Monitoring dissolved oxygen in ground water: some basic considerations. Groundwater Monit. Remediat. 8(1), 93–97 (1988).

Milenić, D., Vasiljević, P. & Vranješ, A. Criteria for use of groundwater as renewable energy source in geothermal heat pump systems for building heating/cooling purposes. Energy Build. 42(5), 649–657 (2010).

Lee, H. B. & Kim, B. Characterisation of hydraulically-active fractures in a fractured granite aquifer. Water SA 41(1), 139–148 (2015).

Fowler, S. W. & Knauer, G. A. Role of large particles in the transport of elements and organic compounds through the oceanic water column. Prog. Oceanogr. 16(3), 147–194 (1986).

Small, L. et al. Role of Plankton in the Carbon and Nitrogen Budgets of Santa Monica Basin, California 57–74 (Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1989).

Conley, W. J. & Turner, J. T. Omnivory by the coastal marine copepods Centropages hamatus and Labidocera aestiva. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Oldend. 21(1), 113–120 (1985).

ANZECC and ARMCANZ, National Water Quality Management Strategy. Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality, R.M.C.o.A.a.N.Z. Australianan and New Zealand Conservation Councile & Agriculture, Editor. Canberra, Australia.(2000).

Li, M. H. Toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid to plants and aquatic invertebrates. Environ. Toxicol. Int. J. 24(1), 95–101 (2009).

Krupa, P. M. et al. Chronic aquatic toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) to Ceriodaphnia dubia, Chironomus dilutus, Danio rerio, and Hyalella azteca. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 241, 113838 (2022).

Sanderson, H. et al. Ecological impact and environmental fate of perfluorooctane sulfonate on the zooplankton community in indoor microcosms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 21(7), 1490–1496 (2002).

Sanderson, H. et al. Effects of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid on the zooplanktonic community. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 58(1), 68–76 (2004).

Boudreau, T. et al. Laboratory evaluation of the toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) on Selenastrum capricornutum, Chlorella vulgaris, Lemna gibba, Daphnia magna, and Daphnia pulicaria. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 44(3), 0307–0313 (2003).

Simpson, S. L. et al. Chronic effects and thresholds for estuarine and marine benthic organism exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS)-contaminated sediments: Influence of organic carbon and exposure routes. Sci. Total Environ. 776, 146008 (2021).

Soucek, D. J. et al. Perfluorooctanesulfonate adversely affects a mayfly (Neocloeon triangulifer) at environmentally realistic concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 10(3), 254–259 (2023).

MStJ, W., et al., Revised Method for Deriving Australian and New Zealand Water Quality guideline Values for Toxicants. Prepared for the Council of Australian Government’s Standing Council on Environment and Water (SCEW). Department of Science. Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane, Queensland, (2015).

Dunlop, J. et al. Assessing the toxicity of saline waters: the importance of accommodating surface water ionic composition at the river basin scale. Australas. Bull. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Chem 2(2), 1–15 (2015).

Kefford, B. J., Papas, P. J. & Nugegoda, D. Relative salinity tolerance of macroinvertebrates from the Barwon river, Victoria Australia. Mar. Freshwater Res. 54(6), 755–765 (2003).

Butler, B. & Burrows, D.W. Dissolved Oxygen Guidelines for Freshwater Habitats of Northern Australia. (2007).

Warne, M.S.J., et al., Revised Method for Deriving Australian and New Zealand Water Quality Guideline Values for Toxicants. Department of Science. Information Technology, Innovation for the Arts (QLD, AU), (2018).

Batley, G. et al. Technical Rationale for Changes to the Method for Deriving Australian and New Zealand Water Quality Guideline Values for Toxicants (Australian Government Standing Council on Environment and Water, Canberra, 2014).

Boudreau, T. M. et al. Response of the zooplankton community and environmental fate of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid in aquatic microcosms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 22(11), 2739–2745 (2003).

Rhyne, A. L., Ohs, C. L. & Stenn, E. Effects of temperature on reproduction and survival of the calanoid copepod Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus. Aquaculture 292(1–2), 53–59 (2009).

Kennedy, A. J. et al. Sensitivity of the Marine Calanoid Copepod Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus to Copper, Phenanthrene, and Ammonia. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 38(6), 1221–1230 (2019).

Mitchell, R. J. et al. Toxicity of fluorotelomer carboxylic acids to the algae Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata and Chlorella vulgaris, and the amphipod Hyalella azteca. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 74(8), 2260–2267 (2011).

Bartlett, A. J. et al. Lethal and sublethal toxicity of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in chronic tests with Hyalella azteca (amphipod) and early-life stage tests with Pimephales promelas (fathead minnow). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111250 (2021).

Logeshwaran, P. et al. Exposure to perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) but not perflurorooctanoic acid (PFOA) at ppb concentration induces chronic toxicity in Daphnia carinata. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144577 (2021).

USEPA, Final Freshwater Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria and Acute Saltwater Benchmark for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), O.o.S.a.T. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water, Health and Ecological Criteria Division, Editor. Washington, D.C. (2024).

Drottar, K. & Krueger, H. PFOS: A 96-hr shell deposition test with the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Wildlife International, Ltd., Project, 454A-106, 2000.

Mhadhbi, L. et al. Ecological risk assessment of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in marine environment using Isochrysis galbana, Paracentrotus lividus, Siriella armata and Psetta maxima. J. Environ. Monit. 14(5), 1375–1382 (2012).

Han, J. et al. Developmental retardation, reduced fecundity, and modulated expression of the defensome in the intertidal copepod Tigriopus japonicus exposed to BDE-47 and PFOS. Aquat. Toxicol. 165, 136–143 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the funding and facility support from the crc for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment (crcCARE) and the Global Centre for Environment Remediation, the University of Newcastle, Australia. We also thank BHP Group Limited and Stantec Inc (Dr Erin Thomas, Mathew Hourston and team) for their support in sample collection, Dr Peter Serov from Stygoecologia for support in species analysis, and Dr. Yun Lin and Dr Huiming Zhang from the EMX unit UON for their support and guidance in improving the image quality for the morphological and SEM analysis.

Funding

This research received was funded by crc for Contamination Assessment and Remediation of the Environment (crcCARE) (G2000912).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wijayawardena M.A.A—conceptualization, methodology, investigation, original draft, and formal analysis. Liu Y.—conceptualization, supervision, investigation, formal analysis, reviewing and editing. Naidu R—supervision, conceptualization, reviewing and editing, validation, resources. Yan K.—investigation, reviewing and editing. Kudagamage C. D.—investigation, reviewing and editing. Carroll T.—methodology, resources, reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wijayawardena, M.A.A., Liu, Y., Naidu, R. et al. Moderate mortality of groundwater copepods Diacyclops humphreysi after exposure to perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Sci Rep 15, 41805 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25654-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25654-5