Abstract

To examine the prevalence of sleep disorders, work–family conflict, and job burnout among shift-working nurses and to analyse the mediating role of shift-related sleep disorders in the relationship between work–family conflict and job burnout within this population. A convenience sampling method was used to select 401 registered on-duty shift nurses from a tertiary grade A hospital in China for a questionnaire survey. The survey utilized a general information questionnaire, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Maslach Burnout Inventory - General Survey (MBI-GS), and the Work–family Conflict Scale (WFC). Multiple hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted to explore the mediating role of sleep disorders in the relationship between work–family conflict and job burnout. Ultimately, 363 shift nurses participated in the survey, and the average sleep quality score was 9.29 ± 3.68. The average score for work–family conflict was 70.19 ± 17.62. The average score for burnout was 2.32 ± 0.57. Work–family conflict was positively correlated with sleep disorders and burnout, and sleep disorders played a mediating role in the relationship between work–family conflict and burnout, with a mediating effect of 0.0566, accounting for 15.77% of the total effect. Nursing managers should pay close attention to the hazards of sleep disorders caused by shift work. By reasonably allocating nursing human resources and improving shift schedules, managers can ensure that nurses get adequate rest after night shifts. Nursing managers should also focus on providing psychological support to reduce the occurrence of sleep disorders among shift nurses. Nurses themselves should actively seek family support, develop good sleep habits and improve sleep quality to enhance their professional health and ensure patient safety and care quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Shift nurses are those who, in addition to their typical daytime work hours, also take work shifts in the early evening or night or rotate between work shifts1. Nurses, who play a crucial role in providing continuous 24-hour health care services to ensure the continuity of care, are an essential component of the health care system and account for 59% of all health workers globally. Shift work is an inherent aspect of their profession2. Previous research has demonstrated that shift work disrupts the normal sleep‒wake cycle and increases the risk of developing shift work-related sleep disorders. A sleep disorder refers to a pattern of sleep with an abnormal sleep quantity or quality, which manifests as a shortened sleep duration, decreased deep sleep time, increased frequency of waking at night, and difficulty falling asleep or waking up too early3. Previous studies from around the globe have reported that the prevalence of sleep disorders among nurses is 32.4%~37.6%4.

Sleep disorders caused by shift work can cause metabolic hormone secretion disorders, leading to diabetes, cardiovascular system disorders, gastrointestinal diseases and other diseases5,6. Moreover, sleep disorders can reduce work efficiency and increase the risk of errors and impair patient safety7. According to previous studies, approximately 57%~83.2% of shift nurses worldwide experience sleep problems8. The high prevalence of sleep disorders among shift nurses is increasingly acknowledged as a critical concern at both the individual and organizational levels. This is particularly significant given that shift nurses are consistently exposed to a high-intensity, high-stress work environment, which contributes to an escalating prevalence and severity of job burnout.

Burnout (occupational burnout), also known as “job burnout”, “work burnout” or “job exhaustion”, is a psychological syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal achievement in a “people serving” profession because of long-term emotional and interpersonal stress9. A study of 351 Omani nurses by Al Sabei et al. revealed that approximately 65.6% of them experienced a high level of burnout10. Burnout not only leads to low work efficiency, poor nursing quality and a high incidence of adverse events but also negatively affects the physical and mental health of nurses, and nearly one-third of nurses quit due to burnout11,12. In addition, work–family conflict (WFC) is positively correlated with burnout13. The higher the degree of WFC is, the more obvious the perceived burnout is.

WFC refers to role conflict caused by the incompatibility of work roles and family roles14. WFC is an important factor affecting nurses’ work attitudes and family quality of life. Studies in China have shown that 50% of nurses have long-term or chronic WFC experiences15. The more obvious the WFC is, the more anxious and depressed nurses will be, and they will be unable to devote themselves to work, resulting in low enthusiasm for work, poor service attitudes, and an aggravated degree of burnout16. Han S et al.17 and Hwang et al.18 reported that higher WFC was positively correlated with burnout. Similarly, Guo Yinan’s study19 revealed that nurses with higher levels of burnout had higher WFC.

Studies have shown that work–family conflict affects not only job burnout but also sleep quality15. Work–family conflict, particularly the impact of work demands on family life, leads to time-based conflicts and psychological stress among shift nurses, which in turn contributes to sleep disturbances and related disorders20. Studies have shown that the incidence of WFC among nurses is on the rise21, which is related to the high requirements of their working conditions, including heavy shift work, physical or emotional workload, and sleep quality problems22. Sleep quality directly affects WFC. Studies have shown that the total sleep quality score of nurses is positively correlated with work–family conflict; that is, the poorer the sleep quality of nurses is, the greater the perceived work–family conflict23. Research on the relationships among sleep disorders, family conflicts and job burnout has become relatively mature. However, limited research has been conducted to explore the relationships among the three factors and their underlying mechanism. In particular, few studies have investigated the impact on the shift nurse population. According to conservation of resources (COR) theory24, the influence of sleep, as a key resource, buffers stress. When WFC disrupts sleep (resource loss), the risk of burnout increases. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore whether sleep disorders explain (mediate) why WFC leads to burnout among shift nurses. The association between WFC and burnout among shift nurses was also examined.

Participants and methods

Participants

A total of 363 shift nurses from a tertiary hospital in Zhejiang, China, were selected as research participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: individual who have obtained a nurse practice qualification certificate; have independently worked in shifts for more than half a year; and voluntarily agreed to participate after being informed about this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: those who were on leave or who were attending further studies outside the hospital; were pregnant or lactating; and have any major physical or mental diseases. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital, with ethical approval number K2025038.

Methods

Tools

Self-designed demographic sociology questionnaire

The questionnaire was designed by the researchers and was used to investigate the participants, including questions about age, education, professional title, marital status, number of children, length of service, employment mode, working shift, number of night shifts per month, etc.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

Developed and published in 1989 by Buysse et al.25 from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, the PSQI consists of 19 items covering seven dimensions: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Scores are given on a four-point scale of 0, 1, 2, and 3. The total score is calculated by summing the scores of all the components and ranges from 0 to 21 points. A score > 7 on the PSQI is considered a criterion for classification; a score ≤ 7 indicates no sleep disorder, whereas a score > 7 suggests the presence of a sleep disorder, with higher scores indicating more severe sleep disorders. In 1995, Liu Xianchen et al. conducted a study in which diverse populations were selected to rigorously evaluate the reliability and validity of the instrument. The results demonstrated high levels of internal consistency (0.8420), split-half reliability (0.8661), and test-retest reliability (0.8092). Furthermore, both construct validity and empirical validity exhibited significant positive correlations.

Maslach burnout Inventory-General survey (MBI-GS)

This scale is evaluated on the basis of the general version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS), which was translated and revised by Li Chaoping et al. in 200326. The scale consists of 22 items, covering three main dimensions—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement—and uses a 7-point Likert scale for the answers. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale score is 0.738, with Cronbach’s α coefficients for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal achievement being 0.858, 0.761 and 0.757, respectively, indicating good reliability and validity.

Work–family conflict scale

This scale was developed by Carlson et al. in 200027. It includes five dimensions and supplements the five specific dimensions, totalling 18 items. A 5-point Likert scale is used for the answers. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of WFC. In this survey, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale is 0.957, indicating good reliability.

Survey method

This study adopted the convenience sampling method and used an anonymous online questionnaire. The participants were informed about the study, and after providing their consent, they were given a unified set of instructions to explain the purpose, significance, completion method, and precautions of the survey, ensuring the confidentiality of their data. No personal information was involved, and the participants completed the questionnaire on their own. The estimation of the sample size took into account the requirements of multivariate analysis. A common rule of thumb suggests that the ratio of participants to variables (dimensions) be between 5:1 and 10:1. Through literature review, the general information questionnaire in this study included 21 variables, seven dimensions of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Scale, three dimensions of the Burnout Scale, and five dimensions of the Family Conflict Scale, totaling 36 variables. The minimum sample size was determined at 10 times the moderating variable, and then with a sample missing rate of 20%, the final minimum sample size was at least 225 cases. In this study, 401 shift nurses were enrolled. After 38 questionnaires that do not meet the requirements were excluded, 363 shift nurses were ultimately included for analysis, resulting in an effective response rate of 90.52%.

Statistical analysis

SPSS26.0 software was used for data analysis. Demographic and sociological data are presented as frequencies and percentages, while sleep quality, WFC and burnout scores are presented as the mean and standard deviation. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to analyse the relationships among sleep disorders, WFC and burnout. Multiple stratified linear regression was used to analyse the mediating effect of sleep disorders on WFC and burnout. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. We assessed the significance of the mediating effects using bootstrapping procedures. Specifically, we generated 5,000 bootstrap samples to derive bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects. An indirect effect was considered statistically significant when its confidence interval did not include zero.

Results

Demographic and sociological data

This study investigated a total of 363 nurses. The demographic characteristics revealed that females constituted the majority (85.1%, n = 309), with 66.9% of the nurses being under 30 years old. Educational background was predominantly a bachelor’s degree (96.1%, n = 349), and 58.7% were unmarried, while 40.5% were married. In terms of family structure, 66.7% of the nurses had no children, and 22.9% had one child.

In terms of occupational title, 56.7% (n = 206) were senior nurses, and 28.7% (n = 104) were nurses in charge. The length of service was generally less than 5 years (44.6%, n = 162). The departments of medicine (32.8%, n = 119) and surgery (28.1%, n = 102) accounted for the greatest proportion.

With respect to shifts and workload, 65% (n = 236) of the nurses worked in the 12-hour system (two-shift), whereas 35% (n = 127) worked in the 8-hour system (three-shift). Among those working in the three-shift system, 72.44% (92/127) of the nurses reported taking night shifts more than 10 times per month. Among those working the 12-hour night shift, 65.7% (155/236) were scheduled to work 5 ~ 10 night shifts per month. During night shifts, 62.81% (n = 228) of nurses typically worked with fewer than 5 colleagues, and 51.52% (n = 187) independently managed 15 ~ 30 patients during night shifts.

After night shifts, 83.5% (n = 303) of the nurses received two days of regular rest. During night shifts, 49.3% (n = 179) of nurses reported “almost no opportunity to sleep”. Among those who could rest, 54% (n = 196) could only sleep for less than one hour each time. On average, 75.2% of the nurses worked 40 ~ 50 h per week, while 5.8% (n = 21) worked more than 50 h. (See Table 1)

Scores for sleep disorders, work–family conflict and burnout

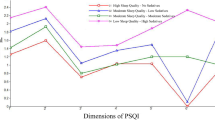

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score was 9.29 ± 3.68, with the lowest score for habitual sleep efficiency (0.73 ± 0.90); the most significant issues were sleep latency (1.78 ± 0.95), sleep disturbances (1.27 ± 0.68) and daytime dysfunction (2.12 ± 0.86). The standardized total SS score for burnout was 2.32 ± 0.57, specifically for emotional exhaustion (21.00 ± 10.08), depersonalization (7.22 ± 5.01), and low levels of personal achievement (25.42 ± 8.72); the work–family conflict scale score was 70.19 ± 17.62 (range 18–90). See Table 2.

Correlations among sleep disorders, work–family conflict and burnout

A correlational analysis of the variables in this study revealed that the total score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was significantly positively correlated with each subdimension of sleep (r = 0.570 ~ 0.772, p < 0.01), with subjective sleep quality (Dimension A) contributing the most to the total score (r = 0.772), whereas habitual sleep efficiency (Dimension D) had a relatively weaker association (r = 0.570). The total burnout score was moderately positively correlated with the total PSQI score (r = 0.323; p < 0.01), and emotional exhaustion was strongly associated with sleep disorders (Dimension E; r = 0.333) and daytime dysfunction (Dimension G; r = 0.587) (p < 0.01). The total WFC score was significantly correlated with the PSQI score (r = 0.287) and burnout score (r = 0.379) (p < 0.01), with the stress dimension strongly correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = 0.555; p < 0.01). However, low levels of personal achievement were not significantly associated with the total PSQI score (r=−0.01; p > 0.05), but it was moderately positively correlated with the total burnout score (r = 0.393; p < 0.01) and weakly negatively correlated with WFC (r=−0.139; p < 0.01). See Table 3.

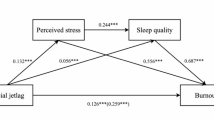

Mediating effect of sleep disorders on work–family conflict and burnout among shift nurses

Stratified regression was used to analyse the mediating effect of sleep quality. All three regression models were significant (P < 0.001). Regression Model 1 revealed that WFC significantly affected sleep quality (β = 0.2536, P < 0.001). Regression Model 2 revealed that both WFC and sleep quality significantly influenced burnout (P < 0.001), with the direct effect of WFC on burnout being 0.3022. Regression Model 3 revealed that the total effect of WFC on job burnout was 0.3588. Integrating the data from the three regression models, the mediating effect of sleep quality between WFC and burnout was 0.0566, accounting for 15.77% of the total effect. See Table 4; Fig. 1.

Discussion

Current knowledge on family conflict, burnout and sleep disorders among shift nurses

The results revealed that the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score of shift nurses was 9.29 ± 3.68, indicating that sleep disorders were prevalent. Among the dimensions, the lowest score was for habitual sleep efficiency (0.73 ± 0.90), and the most significant problem was sleep latency (1.78 ± 0.95), which was consistent with the findings of Feng Huiling28. These findings were consistent with the construction and validation of a clinical prediction model for sleep disorders among nurses, revealing that shift nurses were more prone to low sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, and daytime dysfunction and longer sleep latency. In 2022, through a meta-analysis, Chu Xinyue et al. reported that the prevalence of sleep disorders among nurses in China was 49.9%29. This study revealed that 67.2% of shift nurses suffer from sleep disorders, which was higher than the national average. This was related to the sample size being all shift nurses in this study. This may be associated with the rapid development of health care in recent years, leading to a shortage of nursing staff, an increased frequency of shifts, and high levels of work pressure, all of which can cause sleep disorders.

Long-term night shifts cause the circadian rhythm to become out of sync with the external environment, leading to hormonal imbalances and serious health risks30. Shift work sleep disorders also reduce productivity and increase the risk of errors and impair patient safety33. Therefore, reducing the impact of shift work on nurses’ sleep and health is imperative. Nursing managers can address the factors and mechanisms that lead to sleep disorders caused by shifts and intervene in various ways to improve sleep quality and ensure the occupational health of nurses. Shift nurses should also recognize the impact of shift-related sleep disorders on themselves and actively intervene by establishing good sleep hygiene to help improve their sleep quality. Studies have shown that light therapy can reduce drowsiness and increase alertness among night shift nurses. Additionally, on the basis of the effects of light on the human body, shift nurses should be guided to apply strategic light avoidance measures, such as wearing sunglasses on the way home or using blackout curtains during daytime rest periods, to enhance their sleep quality after shifts31.

With respect to measures to address the circadian rhythm changes caused by shift work, scientific coffee consumption and napping therapy have also shown good results. For example, a 20-minute to 1-hour nap before or during night shifts can offset fatigue from rotating shifts, increase alertness, and reduce errors; drinking coffee (40 mg/kg) 30 min before night shifts can effectively alleviate subjective drowsiness without affecting sleep after the night shift32. The establishment of regular sleep habits after night shifts and the development of good sleep hygiene are also effective measures for improving the quality of sleep after night shifts33. Studies have also shown that long-term, regular exercise can improve sleep quality by increasing slow wave stability and shortening sleep latency34. Park35 reported that nurses who consume protein-rich foods (such as milk and eggs) have better sleep quality, possibly because of the high levels of tryptophan and vitamin B in these foods, which help promote sleep. Shift nurses can explore exercise‒diet coordination plans suitable for themselves, such as the timing effect of supplementation with whey protein after aerobic exercise, to establish a health management strategy for themselves.

The score for burnout SS was 2.32 ± 0.57, which indicated moderate burnout (1.50 ≤ SS < 3.50). Specifically, it manifests as emotional exhaustion (21.00 ± 10.08) and depersonalization (7.22 ± 5.01), both of which are at moderate levels, and low levels of personal achievement (25.42 ± 8.72), which is consistent with the findings of Fan Mengtian et al.36. The results of the study revealed that low achievement was consistently associated with the highest score. In the study of Wang Dongli et al.37, low personal achievement was the most severe issue among nurses. This may be due to tertiary hospitals receiving more medical services, with patients having complex conditions, leading to high work pressure for nurses. Moreover, 66.9% of the shift nurses were under 30 years old, a group with relatively little working experience. When facing emergencies at work, misunderstandings and blame from patients, they lack flexible coping strategies. Day after day, they struggle to manage various shifts, making them more prone to physical and mental exhaustion, loss of enthusiasm and confidence in their work, and emotional depletion. They also find it difficult to experience the sense of achievement that comes from their profession. Therefore, it is suggested that nursing managers focus on cultivating personal achievement among nurses, listen to the inner needs of shift nurses, reasonably plan their rest times and night shift schedules, and provide motivational education to guide nurses towards positive thinking. This helps nurses feel and enhance their professional achievements, reduce negative emotions, and lower burnout.

The work–family conflict scale score (70.19 ± 17.62) was high, with 37 ± 8.559 for the time dimension, 17.18 ± 5.53 for the stress dimension, and 16 ± 6.468 for the behaviour dimension. Time dimension issues are prominent, possibly because night shifts disrupt the living routines of shift nurses, leading to biological clock disorders. After shifts, these nurses need to catch up on sleep, making it difficult for them to take care of family responsibilities, which can easily result in conflicts between work and family life. Compared with single individuals, married individuals exhibit more pronounced WFCs. They not only have to manage family matters but also excel in clinical and even research work. The transition between professional and personal roles is challenging, thus causing greater conflict in both work and family life. Huang Xiaoli’s38 research also indicated that health care workers, owing to their high workload, exhibit higher levels of family-work conflict, leading to increased burnout, which in turn affects their intention to leave. These findings suggest that nursing managers should pay attention to the impact of nurses’ work on family conflicts, provide timely emotional and resource support, and reasonably utilize human resources by appropriately reducing shift frequency. This can help reduce family-work conflict for on-duty nurses, thereby improving overall nursing quality.

Mediating effect of sleep disorders on family conflict and burnout among shift nurses

The results of this study revealed that WFC and sleep disorders were positively correlated with burnout and that WFC and sleep disorders could predict the level of burnout positively, suggesting that the more prominent WFC and sleep disorders were, the higher the level of burnout was. This study revealed that family–work conflict among shift nurses not only directly affects burnout but also indirectly affects it through sleep disorders. The results revealed that sleep disorders partially mediated the relationship between work–family conflicts and burnout, which accounted for 15.77% of the total effect. These findings indicated that improving sleep disorders and enhancing sleep quality could alleviate WFC, thereby helping to reduce levels of burnout.

These findings were consistent with those of a cross-sectional study in South Korea, which confirmed that burnout prevention strategies should focus on addressing nurses’ sleep disorders to mitigate the impact of WFC on burnout39. Therefore, good sleep is necessary for normal work and life. Sleep disorders among shift nurses threaten their own health, nursing quality and patient safety. The strategy to optimize the sleep quality of nurses needs to be coordinated between the organizational level and the individual level, integrating diversified measures and promoting them40. Therefore, nursing managers should pay attention to the effects of shift work as an environmental stimulus on nurses’ sleep and occupational health. In daily scheduling, they should focus on combining flexible shifts with tiered management, reasonably allocating nurse human resources, reducing the frequency of shift rotations for nurses, optimizing shift intervals, avoiding consecutive shifts, and lowering workloads while ensuring that nurses achieve adequate rest during night shifts. Managers also need to provide psychological support and health education to reduce the occurrence of shift work-related sleep disorders among nurses; shift workers should actively seek family support and emphasize the dissemination of relevant knowledge about their spouses and family members. Hospitals can regularly hold family liaison days to educate relatives at the nursing department level about shift work-related sleep disorders, helping them understand the risks and preventive measures and providing more support from a family perspective. Shift workers should also develop good sleep habits, improve sleep hygiene, promote occupational health, and ensure the quality of care and patient safety.

Application of the results in clinical nursing practice

The findings of this study highlight the critical challenges faced by shift nurses, including prevalent sleep disorders (PSQI score: 9.29 ± 3.68), moderate-to-severe burnout (SS score: 2.32 ± 0.57), and high work-family conflict (WFC score: 70.19 ± 17.62). These issues are interrelated, with sleep disorders mediating 15.77% of the effect of WFC on burnout. To address these problems, multilevel interventions are recommended.Organizationally, integrate comprehensive sleep health and work-family conflict (WFC) management protocols into hospital occupational health policies, establishing clear institutional accountability measures for nurse well-being.Systematically reduce workload pressure through strategic allocation of nursing human resources and implementation of psychological support systems, including on-site counseling services and regular stress-management workshops. Develop structured family engagement programs such as quarterly “Nurse Family Liaison Days” to improve familial understanding of shift-work challenges and foster practical support networks38.Individually, nursing staff should actively participate in and utilize these organizational support systems, while maintaining open communication with supervisors about workload concerns.Apply learned stress-reduction techniques from workplace workshops in daily practice to better manage work-life balance challenges.Systematically, these coordinated organizational policies and individual practices, when combined with optimal shift scheduling32 and evidence-based sleep interventions (e.g.,light therapy31, nutritional strategies34,35, create a sustainable framework for improving nurse well-being, sleep quality, and job performance.By addressing sleep disorders as a modifiable mediator, nursing leaders can indirectly reduce burnout and enhance care quality, ultimately safeguarding both nurse health and patient safety.

Conclusion

Shift nurses experience higher levels of WFC, sleep disorders, and burnout. The greater the WFC is, the higher the degree of burnout. Sleep disorders serve as a mediating variable between WFC and burnout among shift nurses. Nursing managers should prioritize the sleep health of shift nurses by establishing a scientific shift system to avoid high-risk scheduling, prohibit consecutive 3 or 4 night shifts, ensure at least 24 h between shifts to guarantee adequate rest time, and implement “family friendly” shift policies to alleviate WFC and reduce burnout. Simultaneously, sleep health management and dietary health should be incorporated into professional training, making shift nurses aware of the harm caused by sleep disorders to themselves and their careers, and they should work with nursing managers to construct a sleep health management system to ensure occupational safety.

Strengths and limitations

This study goes beyond simply exploring the direct relationship between work–family conflict and job burnout and delves deeply into revealing the potential key “mediating mechanism” of “sleep disorders”. This helps explain “why” work–family conflicts lead to job burnout. Moreover, among the special group of shift nurses, relatively few studies have systematically investigated sleep disorders as a mediating variable. This study addresses an important knowledge gap. This project is a study involving staff at a Grade A tertiary hospital in China. Although its universality needs further exploration, it has reference significance for hospitals of the same level.

Owing to the limitations of the research and personal conditions, the sampling scope was limited to a specific tertiary hospital in Zhejiang Province. Thus, the sample of this study may be not be representative enough. Whether the research results can reflect the common characteristics of tertiary grade A nurses remains to be further explored in the future. Furthermore, this study is merely cross-sectional. Sleep disorders, family conflicts and job burnout among nurses are dynamic processes and cannot be tracked longitudinally because of variable changes. Therefore, future research should focus on longitudinal, large-scale, multicentre and prospective intervention studies. Moreover, during the research process, sleep quality can be measured with objective data, such as using activity tracking devices or polysomnography (PSG), to reduce the bias of subjective data.

Data availability

Data openly available in a public repository. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [Mendeley Data].Data will be made available on request. Please contact the corresponding author(yanchengli1208@zju.edu.cn), if someone wants to request the data from this study. (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ct84wgjbz8/1)

References

Min, A. & Hong H C, Kim, Y. M. Work schedule characteristics and occupational fatigue/recovery among rotating-shift nurses: a cross-sectional study[J]. J. Nurs. Manag. 30 (2), 463–472 (2022).

Anna, B. et al. Risk factors of metabolic syndrome among Polish nurses. [J] Metabolites. 11 (5), 267–267 (2021).

K K G,Mohan, V. K. Sleep disorders in the elderly: a growing challenge. [J] Psychogeriatr. : Official J. Japanese Psychogeriatr. Soc. 18 (3), 155–165 (2018).

Elisabeth, F. et al. Shift work disorder in nurses–assessment, prevalence and related health problems. [J]. PloS One. 7 (4), e33981 (2012).

Azmi, M. S. et al. Consequences of Circadian Disruption in Shift Workers on Chrononutrition and their Psychosocial Well-Being [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17 (6): 2043. (2020).

Anonymous Shift workers at risk for metabolic syndrome [J]. Prof. Saf. 65 (8), 12–12 (2020).

Deng, N. et al. The relationship between shift work and men’s health [J]. Sex. Med. Reviews. 6 (3), 446–456 (2017).

Qiuzi, S. et al. Sleep problems in shift nurses: A brief review and recommendations at both individual and institutional levels. [J] J. Nurs. Manage. 27 (1), 10–18 (2018).

Maslach, C. & Jackson, S. E. The measurement of experienced burnout[J]. J. Occup. Behav. 2, 99–113 (1981).

Ann, K. G. et al. Thriving among primary care physicians: a qualitative Study. [J]. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 36 (12), 1–7 (2021).

X Z,W K, S S et al. A causal model of thriving at work in Chinese nurses. [J] Int. Nurs. Rev. 68 (4), 444–452 (2021).

Qing-sen, H. E. CAO Shan, JING Xiao-lei, LIU Ling-xia.Mediating effect of psychological empowerment between servant leadership and thriving at work in clinical nurses[J]. J. Nurs. 30 (6), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2023.06.047 (2023).

Jun, P. et al. The effect of psychological capital between work-family conflict and job burnout in Chinese university teachers: testing for mediation and moderation. [J]. J. Health Psychol. 22 (14), 1799–1807 (2017).

Chen Changrong, C. & Chunping, Z. The investigation of work-family conflict among nurses [J]. Chin. J. Nurs. 45 (7), 629–631 (2010).

Cheng, S. Y. et al. Sleep quality mediates the relationship between work-family conflicts and the self-perceived health status among hospital nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 27 (2), 381–387 (2019).

Chen Bufeng, W. et al. Effect of the family-work conflict on the occupational stress and burnout of medical staff [J]. J. Community Med. 16 (24), 1757–1759 (2018).

Sujeong, H. & Sungjung, K. The effect of sleep disturbance on the association between work-family conflict and burnout in nurses: a cross-sectional study from South Korea. [J]. BMC Nurs. 21 (1), 354–354 (2022).

Eunhee, H. & Yeongbin, Y. Effect of sleep quality and depression on married female nurses’ Work–Family Conflict[J]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health.18 (15), 7838–7838 (2021) .

Guo Yinan, X. et al. work-family conflict and associated factors among nurses at different reproductive States [J]. J. Nurs. Sci. 33 (19), 58–60 (2018).

Wu Xiaoxian, L. & Fang, X. The influence of work-family conflict on depression of cardiology nurses:the mediating role of sleep quality [J]. J. Nurs. Adm. 22 (07), 473–478 (2022).

Yildiz, B., Yildiz, H. & Ayaz, A. O. Relationship between work–family conflict and turnover intention in nurses: a meta–analytic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 77 (8), 3317–3330 (2021).

Hwang, E. & Yu, Y. Effect of sleep quality and depression on married female nurses’work–family conflict. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (15), 7838 (2021).

Sisi Chen,Dongyue Zheng,Qiyu Chen. Study on the relationship between Work-Family conflict and sleep quality for operating room nurses [J]. Hosp. Manage. Forum. 34 (06), 44–47 (2017).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at con-ceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44 (3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 (1989).

Liu Xianchen, T. et al. Reliability and validity of Pittsburgh sleep quality index [J]. Chin. J. Psychiatry. 29 (02), 103–107 (1996).

Li Chaoping, S. et al. An investigation on job burnout of Doctor and nurse [J]. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 17 (03), 170–172 (2003).

Carlson, S. D., Kacmar, K. & ,Williams, J. L. .Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of Work–Family Conflict[J]. J. Vocat. Behav. 56 (2), 249–276 (2000).

Feng Huiling. Development and validation of a clinical prediction model for shiftwork sleep disorder among Chinese nurses [D]. Chin. Med. Univ. https://doi.org/10.27652/d.cnki.gzyku.2022.001757 (2022).

Chu Xinyue, W., Yulan, L. & Wei Prevalence Rate and Influencing Factors of Sleep Disorders in Chinese Clinical nurses:A meta-analysis [J] Vol. 38, 395–399 (OCCUPATION AND HEALTH, 2022). 03.

Jensen, I. H., Larsen, W. J. & Thomsen, D. T. The impact of shift work on intensive care nurses’ lives outside work: A cross-sectional study[J]. J. Clin. Nurs. 27 (3–4), e703–e709 (2018).

Lang Ying, J. et al. Therapeutic effect of light therapy on circadian rhythm for the shift work disorder patients [J]. Chin. J. Clin. Neurol. 21 (03), 284–288 (2013).

Stephanie, C. et al. Coping with shift work-related circadian disruption: A mixed-methods case study on napping and caffeine use in Australian nurses and midwives[J]. Chronobiol. Int. 35(6), 1–12 (2018).

Zhengyan, T. X. L. et al. Psychometric analysis of a Chinese version of the sleep hygiene index in nursing students in china: a cross-sectional study[J]. Sleep Med. 81253–81260 (2021).

Insung, P. et al. Exercise improves the quality of slow-wave sleep by increasing slow-wave stability. [J] Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 4410–4410 (2021).

Hoon, J. P. et al. Associations between the timing and nutritional characteristics of bedtime meals and sleep quality for nurses after a rotating night shift: A Cross-Sectional analysis [J]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (2), 1489–1489 (2023).

Mengtian, F. Study on the mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between psychological resilience and burnout in nurses [J]. China Health Standard Manage. 16 (03), 30–33 (2025).

Wang Dongli, F. et al. Study on the correlation between premenstrual syndrome and job burnout among clinical nursing staff [J]. J. Nurs. Adm. 24 (01), 37–39 (2024).

Huang Xiaoli, L., Yanxia, S. & Yujuan The influence of work-family conflict on the professional identity and intention to leave for a second child nurse [J]. Shanxi Med. J. 49 (20), 2761–2764 (2020).

Sujeong, H. & Sungjung, K. The effect of sleep disturbance on the association between work-family conflict and burnout in nurses: a cross-sectional study from South Korea.[J]. BMC Nursing. 21(1), 354–354 (2022).

Du Jie, Y. & Qiang Li Yamin. Advances in non-pharmacological interventions for sleep quality of shift nurses [J]. Chin. J. Nurs. 60 (05), 629–634 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank all researchers who have contributed to collecting these data.

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific Research Project of the Department of Education of Zhejiang Province (No. Y202454954) and the Zhejiang Medicine and Health Science and Technology Project (No. 2025KY089).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Danlei Zheng, Yuyu Chen contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.Danlei Zheng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Project administration.Yuyu Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Jia Cao: Writing – review & editing. Hui li: Investigation Weiwei Chu: Investigation. Chengli Yan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (K2025038). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, D., Chen, Y., Cao, J. et al. Sleep disorders mediate the relationship between work family conflict and burnout in shift nurses. Sci Rep 15, 41708 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25658-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25658-1