Abstract

With less than two years remaining from 2027—the year which the government has targeted to achieve zero Indigenous cases, we map the malaria indicators across the 700 + districts for five years between 2019 and 2023 using spatiotemporal maps and also assess the potential drivers of malaria transmission in different regions. We used the annual district-wise malaria data from the National Center for Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NCVBDC) and the cross-sectional socio-economic data from the National Family Health Survey. We also collated the meteorological and land-use land-cover data from the MERRA-2 and Sentinel-LPA satellites, respectively. We then developed region-specific ensembles of spatiotemporal models that allowed us to identify the associated covariates while the regions were identified using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistics. With 0.33 million malaria cases in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant reduction in reported cases. The P. falciparum affected regions are widespread in North-eastern and Central India. However, after the pandemic, an emerging geographical expansion into the north-eastern parts is observed for the P. vivax, which is evident from the clusters and the spatiotemporal ensemble models. Population belonging to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes and those economically marginalised are among the most vulnerable, but lifestyle habits such as drinking water practices, maternal education, and healthcare accessibility are associated with malaria transmission. We also developed a digital dashboard that allows the general public and the stakeholders to track the malaria indicators for each district and the corresponding year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria has significantly impacted India’s healthcare infrastructure due to its high incidences1,2,3. Recently, the World Malaria Report 2024 estimated 249 million malaria cases that disproportionately affect the most marginalised population, highlighting equitable access to life-saving tools as the key to reversing malaria trends4. Further, the World Health Organisation’s recently formulated “Global Malaria Programme Operational Strategy for 2024–2030” identified country ownership and accessibility to resilient health systems as well as data-driven decision-making as the road ahead for malaria elimination5. Previously, a need for a holistic framework for data dissemination and a synergistic multilateral framework involving academic, public and private sector involvement was highlighted as a significant targeted measure that could play a pivotal role in India’s journey against Malaria3.

Malaria risk mapping has been proved useful in Africa, where usage of malaria cartography reemerged in the late 1990 s, which also coincided with activities aimed at intensive control and elimination6,7,8. Additionally, there has been a gigantic shift towards the usage of modern statistical methods in developing spatiotemporally detailed maps that are being increasingly applied in informing policies9,10. Spatiotemporal modelling techniques for a comprehensive quantification of malaria burden and research-based insights into the key contributing factors are recommended as an epidemiological prerequisite to intervention strategies6,11.

Previously, in India, geospatial mapping reported that 13% of the country is under very high malaria risks, with a high probability of outbreaks in low to moderate-risk regions12. Further, mapping techniques have been used in surveying the vectors and insecticidal resistance in India13,14,15. Through this work, we first identify the spatiotemporal trends in the malaria parameters from 2019 to 2023 and understand the spatial clusters using maps for all malaria epidemiological parameters. We used an ensemble of Random Forest Regression and Zero-Inflated Poisson Regression to assess the significant covariates that could influence malaria transmission in the three-primary malaria-predominant regions. We then develop a dashboard that visualises the spatial trends and clusters for the general public and the country’s stakeholders.

Methods

Malaria data

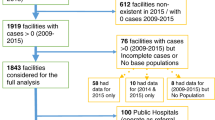

District-level data on the malaria situation for the year 2018–2023 were obtained from the NCVBDC, a Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India department responsible for the control of malaria in India. The parameters included Percentage of Falciparum Cases (% PF), Annual Parasite Incidence (API), Annual Falciparum Incidence (AFI), Annual Blood Slide Examination Rate (ABER), Slide Positivity Rate (SPR), and Slide Falciparum Rate (SFR). More information about these parameters is discussed in16. Further, the Annual Vivax Incidence (AVI) was estimated by subtracting the AFI from API.

Spatial analysis

For the spatial plots, we used the official shapefiles available on the Online Maps Portal, maintained by the Ministry of Science & Technology17. We accessed the official government websites for those districts that were mismatched and standardised the district names to ensure consistency with the available malaria data. This step was essential for accurately mapping and plotting the data. Through this, we retrieved 667 districts in 2019, 674 in 2020, 682 in both 2021 and 2022, and 678 in 2023. We then plotted the spatial distribution for each malaria parameter using Geopandas v.0.14.3 (Bossche et al.18). The spatial clusters were identified using the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic, which is suitable for comparing the global mean of all districts with the local mean of each district and the corresponding neighbouring districts. Districts having standardised z-scores > 0 and p-values < 0.05 were classified as the hotspots where spatial clustering exists. The Getis-Ord Gi* statistic and their methods have been discussed in detail here16,19.

Meteorological, socio-economic and Land-use Land-cover covariates

The meteorological data was collated from the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications version 2, or MERRA-2, which provides monthly advanced reanalysis data at a spatial resolution of 0.5°×0.625°20. We collated the monthly gridded data on surface temperature, precipitation, specific humidity and soil moisture that was overlaid on the district boundaries, for obtaining the district-wise data. This was then aggregated at the annual level to obtain the mean, maximum and minimum for each variable. Data on the land-use land-cover classes were collated from the ESA Sentinel-2 imagery that provided the data at a 10 m resolution21. Using the same procedure of overlaying the data, we obtained the areas for water bodies, tree cover, bare lands, built-up areas, snow land, croplands and flooded vegetation for all districts and each year. For the socio-economic data, we used the Household Recode File from the representative National Family Health Survey-5 conducted between 2019 and 2021 to obtain district-wise household-related information describing the socio-economic characteristics, healthcare choices, nutritional and educational status, and prevalence of common disorders.

Ensemble models

We first identified three distinct regions that have witnessed the highest degree of transmission observed between 2019 and 2023. The clusters that were identified using the Getis-Ord G* statistics, as discussed in 2.2, also belonged to these three regions. The ‘Central’ regions comprised Telangana, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, while the ‘North’ region consisted of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The seven states in north-eastern India, namely Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Tripura, Mizoram and Manipur, comprised the ‘North-eastern’ region.

We then used an ensemble modelling approach where ensembles of Random Forest Regression Models were developed for each year and region to obtain the feature importance for ranking the variables according to their importance. For obtaining the ranked matrices of the most significant variables, a Monte Carlo Simulation was performed, following which we developed three spatiotemporal Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) Regression models for the central, northeast and northern regions of the country separately, as a significant number of districts reported zero API. More information about the methodology can be found in16. In contrast to our previous methodology, we here computed the API per 100,000 people to convert all decimals to integers as required for the ZIP, while no categorical variable for mapping the P. falciparum distribution was introduced. In contrast, we introduced a categorical variable corresponding to the year, accounting for the temporal variations. The spatiotemporal model can be written as:

where i denotes the states and t represents the year. For the present study, the Risk Ratios (RR) and the Odds Ratios (OR) were computed by exponentiating the model coefficients for the Poisson and logistic components in the ZIP model, respectively.

Creation of the ‘MIDAS’ dashboard

We created an interactive dashboard showing the spatiotemporal variations in the malaria parameters. We used a GeoJSON file to load the geospatial data onto the dashboard. The dashboard was developed using the Dash and Plotly22 frameworks available in Python. Previously, the NIMR-MDB dashboard was developed using R but is currently not hosted for viewing by the general public23. We also used data analytical software like Pandas24 and GeoPandas25. Our dashboard was structured into three sections to enhance user experience and effective data exploration. The interactive control panel on the left includes dropdown menus and radio buttons that can be used to filter the data by year, geographical regions (states and districts), and malaria indicators that are of interest. The visualisation area on the right shows the spatial and temporal visualisations, where trends and distributions of malaria incidences are depicted. The third section is the header and footer, which sets a context for the general user. For the visualisation components, we have used choropleth maps and time-series maps that track the indicators over time using interactive illustrations. We name our dashboard “MIDAS”, or the Malaria Indicators Dashboard for Analysis and Surveillance. The dashboard has been successfully tested on an internal server and will be made publicly accessible after requisite approvals.

Results and discussion

Spatiotemporal variations in the malaria parameters across India

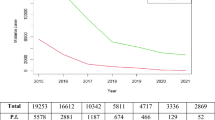

India reported a cumulative of 0.33 million cases in 2019, which dropped to 0.18 million in 2020 - the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a 13.3% reduction in the cases in 2021, but it increased by 9% in 2022 and again by 29% in 2023 when compared to the previous year. The temporal trends for the Blood Slides Collected (BSC) and Examined (BSE), Rapid Diagnostic Kits (RDT) Collected and Examined, and the Total Number of P. falciparum (Pft) and P. vivax (Pvt) cases are provided in Table S1. There was a similar drop in the total blood slides collected and examined from 2019 to 2020, which later started improving from 2021 onwards. However, the SPR marginally increased from 0.252 in 2019 to 0.254 in 2020, which later dropped to 0.18 in 2021 and 0.17 in 2023. Both SFR and % PF were higher than the corresponding Slide Vivax Rate and % P. vivax from 2020 onwards3.

Among the states, Maharashtra had the highest blood slides examined in 2019; however, the neighbouring state of Gujarat reported the highest ABER (24.5), with districts like the Dangs (44.57) and Kachchh (40.29) reporting higher surveillance. In 2019, a P. vivax outbreak in the densely populated districts of Bareilly (34576) and Budaun (18302) in Uttar Pradesh reported the highest proportion (35.4%) of P. vivax in the whole country. Subsequently, both of these districts had SPR > 10. Further, the P. falciparum (% PF > 85) predominant districts of Sukma, Bijapur, Dakshin Bastar Dantewada and Narayanpur in Chhattisgarh, and Lawngtlai, Mamit and Lunglei in Mizoram reported SPR > 5 and API > 15. Interestingly, Nuh in Haryana, which was majorly affected by P. falciparum (84.7%), reported a high SPR of 5.77 but an API of 0.68 and an ABER of 1.18.

In 2020, the same districts in Chhattisgarh and the north-eastern states, along with Malkangiri in Odisha, reported both API and AFI > 10. Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, which borders Bastar to the east, reported a higher API of 7.7 when compared to 2019 (2.09). It was among the districts having the highest surveillance with an ABER of 75.37. In the subsequent years, Gadchiroli reported an API of 10.47 in 2021, 7.79 in 2022 and 5 in 2023, while the SPR was also restricted to below 1. The eastern city of Kolkata, which is among the world’s most densely populated metropolitan cities, has reported API > 2 since 2019, with a maximum of 5.9 in 2022. Except in 2021 (AFI = 1.5; % PF = 33.3), Kolkata reported AFI < 1, while the % PF varied between 5.5 and 14.5, highlighting the significance of P. vivax in the malaria transmission.

We note that P. falciparum-predominant regions have consistently been the same throughout the years – it is primarily dominant in Central India and North-eastern India. Consequently, these are the regions that have reported very high API and AFI > 10. For instance, Lawngtlai in Mizoram has reported very high P. falciparum-based transmission for all five years, which was the maximum for the whole country in 2021 (API = 26.2; AFI = 22.4; SPR: 4.1), 2022 (API = 39.3; AFI = 30.3, SPR: 4.8) and in 2023 (API = 56.2; AFI = 38.9; SPR: 16.6). However, a transition to P. vivax was observed in Northeast India. A very high P. vivax transmission was observed in Lawngtlai, Mamit and Lunglei in Mizoram and Dhalai and South Tripura in Tripura. In Lawngtlai, there was a 213% increase in the AVI in 2020 when compared to 2019. The transmission further intensified in 2022 and 2023, as an AVI of 9.0 and 17.6 was reported in Lawngtai. A similar pattern was observed for the remaining districts (Fig. 3), which also share international borders with Myanmar and Bangladesh. Previously, cross-boundary malaria was highlighted as a potential risk factor for malaria resurgence in the region1,3. The spatial distribution of API across the districts is provided in Fig. 1, while the distribution of AFI and AVI are provided in the supplementary as Figures S1a and S1b, respectively.

Identification of spatial clusters using Getis-Ord Gi* statistics

We classified the districts further based on their Getis-Ord Z-scores and the associated p-values. Districts with z-scores greater than 0 and p-values < 0.05 were classified as hotspots19. We observe that the hotspots are distributed in the similar districts only from 2019 to 2024. For API, these districts are distributed across two distinct regions in the country, namely the Central Region covering Maharashtra (1), Andhra Pradesh (4), Telangana (1), Chhattisgarh (6), and Odisha (2), and the Northeast Region spanning across Assam (2), Mizoram (8), and Tripura (8). An additional zone in the northern parts of the country that covers Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand was observed for AVI. The significant hotspots observed for (a) API, (b) AFI, and (c) AVI are provided in Fig. 2, while the intensity of the reported transmission is provided in Fig. 3. The maps visualising the spatiotemporal distribution of hotspots for API, AVI and AFI are provided as Figure S2, S3 and S4, respectively.

Significant hotspots observed for (a) API, (b) AFI and (c) AVI between 2019–2023. The size of the scatter and the intensity of the colour correspond to the magnitude of the z-scores. Higher the Z-score or bigger the size of the scatter, more intense is the clustering. UP: Uttar Pradesh; UK: Uttarakhand; A&N: Andaman & Nicobar; PU: Puducherry; CH: Chhattisgarh; JH: Jharkhand; OD: Odisha; MH: Maharashtra; AP: Andhra Pradesh; TR: Tripura; MZ: Mizoram; AS: Assam; TL: Telangana.

Spatiotemporal distribution in (a) API, (b) AFI and (c) AVI in districts identified as part of the clusters. The numbers on each box represent the values observed for the malaria parameters in each district (shown on y-axis) and year (shown on x-axis). Few of the districts with zero API also fall in the high-risk zone (Fig. 2) due to high malaria transmission observed in the neighbouring districts. UP: Uttar Pradesh; UK: Uttarakhand; A&N: Andaman & Nicobar; PU: Puducherry; CH: Chhattisgarh; JH: Jharkhand; OD: Odisha; MH: Maharashtra; AP: Andhra Pradesh; TR: Tripura; MZ: Mizoram; AS: Assam; TL: Telangana.

For API, we observe that Bastar (Z-score: 4.95), Dastin Bastar Dantewada (Z-score: 4.71) and Sukma (Z-score: 4.5) in the Central Zone show highly significant clustering in 2019. The neighbouring districts of Narayanpur (Z-score: 3.0), Kondagaon (Z-score: 2.97) and Gadchiroli (Z-score: 2.47) are also identified as hotspots. We observe that these districts show a lesser extent of clustering over the years as their Z-scores reduce below 2 in 2023 (Fig. 2). In contrast, the districts in northeast India, such as Saiha, Lawngtlai, Serchhip, Lunglei, Champai & Mamit, show increasing Z-scores, with the maximum in 2023. For instance, Saiha and Lunglei reported Z-scores of 4.87 and 4.78, respectively. The eight districts in Tripura also reported maximum Z-scores in 2023. Hailakandi in Assam and Kolasib in Mizoram emerged as hotspots in 2023. Further, the districts in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana were identified as hotspots in 2019 and 2020 only.

Similar to the API, the significant hotspots for the AFI were restricted broadly to the central and northeast parts of the country. The districts in the central region exhibited very high clustering between 2019 and 2021, which declined slightly in 2022 and 2023. For instance, Bastar in Chhattisgarh reported a Z-score of 4.77 in 2019, which decreased to 3.76 in 2021 and 2.58 in 2023. The neighbouring districts of Sukma and Dakshin Bastar Dantewada in Chhattisgarh that reported very high Z-scores > 4 also followed a similar trend. In contrast, the clustering in north-eastern districts, especially those in Mizoram (Saiha, Serchhip, Lawngtlai and Champai), reported increased clustering in the later years as the Z-scores were > 4. The clustering in Tripura reported relatively moderate clustering with Z-scores ~ 2.1, which reduced in the later years. A few districts that reported very low transmission, such as Hailakandi in Assam, were also categorised as high-risk areas due to the neighbouring districts reporting very high API (Figure S2).

We observe a geographical shift in the clusters observed for AVI that is also evident in the spatial distribution maps of AVI throughout the years (Figure S1; Sect. 3.1). All five districts that emerged as the focal point of AVI transmission, namely Lawngtlai, Mamit and Lunglei in Mizoram and Dhalai and South Tripura in Tripura, were all classified as hotspots for AVI. Thus, the emergence of P. vivax is occurring in this part of the country that was previously dominated by P. falciparum. In the north, the districts around Bareilly were identified as significant hotspots in 2019 and 2020, but the clustering was not significant in the subsequent years as these regions also witnessed fewer cases (Fig. 1). Likewise, a similar trend was observed in the central region as districts like Sukma and Uttar Bastar Kanker, which are also categorised as significant hotspots for AFI, did not emerge as clusters for AVI post-2021. However, in contrast, the districts in north-eastern India showed very strong clustering after 2021. Districts in Mizoram, such as Saiha, Lawngtai, Lunglei and Serchhip, showed Z-scores > 5 in 2023 and > 4.5 in both 2022 and 2021, while all eight districts in Tripura were classified as significant hotspots with the highest degree of clustering in 2023.

Identifying potential risk factors for malaria transmission using the spatiotemporal ensemble model

Using the region-specific ensemble of Random Forest Regression and Zero-inflated Poisson Regression models, the significant covariates that are likely influencing malaria transmission were identified for each of the parameters, i.e. API, AFI and AVI. The estimated region-wise associations or the Risk Ratios for API, AFI and AVI in districts reporting ≥ 0 are provided in Fig. 4. We observe that for API in the Central Region, % total of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (RR: 2.18 (95% CI: 2.1, 2.27), % population not having mobile (RR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.68, 1.73) and % population who are not having normal BMI (RR: 1.06 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.08) are among the socio-economic determinants positively associated with increased malaria transmission in districts. In our previous work, we found the same factors responsible for the malaria risk for the entire country16. Obesity has been previously identified as a risk factor in Sweden26, while malnutrition was associated with malaria in Cameroon27.

We also observe that % of households (HH) owning livestock is negatively associated with malaria in all regions for API (0.3 < RR < 0.7), but it is positively associated with AVI in the Central (RR: 1.3 (95% CI: 1.19, 1.42). Livestock-based interventions have been recommended as a strategy for controlling malaria28, but the in-house raising of animals in Indonesia29 and the presence of cattle in households in Tanzania were associated with malaria30. Thus, more evidence-based research is needed to ascertain the role of livestock in malaria control. Similarly, a mother’s education is negatively associated with API in all three regions, but we observe a positive association with AVI in the Central Region (RR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.53, 1.88). An educated mother will be aware of the symptoms of malaria. During outbreaks, testing and diagnosis increase due to pre-existing knowledge about the symptoms. This could lead to more cases being reported to the system. Similarly, in the absence of outbreaks, awareness about the prevention measures and careful adoption of the interventions will reduce the risk of malaria31.

Healthcare accessibility, which is indicated by factors such as % of the population accessing treatment from private doctors or public hospitals, is negatively associated with the malaria risk for all regions and parameters. We also observe that % of HH having Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) is positively associated with malaria parameters in multiple regions. The RSBY is a flagship programme of the Ministry of Health, Government of India that offers health insurance coverage to families below the poverty line. Economically marginalised households are more likely to access healthcare facilities due to their health insurance coverage32.

In the north-eastern region, factors such as % HH living in muddy walled structures as well as % HH belonging to the poorest wealth index are positively associated with API, AFI and AVI. Economically disadvantaged communities are among the most vulnerable sections in this region, as earlier reported in Assam33. The percentage of HH using unprotected drinking water from sources like natural springs is also associated with the API (RR: 1.29 (95% CI: 1.28, 1.3) and AFI (RR: 1.24 (95% CI: 1.23, 1.25), as also reported in Ethiopia34. Previously, these muddy houses have been linked to an increased risk of malaria in Mandla, India35. We also observe a significant positive association shown by % HH using Insecticide Treated Nets (ITNs) in the northeast with API (RR: 3.5 (95% CI: 3.36, 3.64), AFI (RR: 2.27 (95% CI: 2.16, 2.39) and AVI (RR: 3.45 (95% CI: 3.2, 3.71). In contrast, the % HH using ITNs had a negative association with the API (RR: 0.15 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.17) and AVI (RR: 0.26 (95% CI: 0.23, 0.29) in the North Region. This implies that outdoor transmission could be responsible for the malaria outbreaks in the north-eastern region. Contrarily, only a few districts, such as Budaun, reported high transmission in the North, and they had a very low proportion (1.7%) of HHs using ITNs. Thus, with less ITN usage, it is likely that the cases increased during outbreaks.

Additionally, in the north, we also observe that both % of the population using rainwater for drinking purposes and % of the population fetching water elsewhere for household usage (RR: 4.54 (95% CI: 4.19, 4.9) are very strongly associated with the API. In Kolkata and Chennai, Anopheles Stephensi has reportedly been found in overhead water tanks, which had been kept open by residents to collect rainfall for later usage36. Thus, water storage practices in this northern belt could be responsible for the increased outbreaks. The 2018 outbreak in Bareilly, a district in Uttar Pradesh, was also attributed to excessive rainfall, along with poor surveillance37. Moreover, travelling to fetch water has been linked to increased cases in Africa38,39. In the northeast, we observe that % of HH having a water source in their own yard is also positively associated with the AVI (RR: 1.55 (95% CI: 1.42, 1.7). In Tanzania, increasing coverage of non-piped water was associated with rising malaria cases40. Additionally, the prevalence of tobacco non-smokers was positively associated with malaria in the north. In Nigeria, decreased endophily for Anopheles was previously reported in a room that was habitated by smokers; however, the role of tobacco smoking habits needs to be investigated41.

The forested land area defined by the ‘Trees’ variable was positively associated with API, AFI and AVI in both the Central and Northeast regions. This was complemented by the meteorological variables like the maximum of both precipitation and specific humidity. In the north, agricultural land defined by the LULC variable ‘crops’ was positively associated with both API and AVI. To investigate the temporal factor, the categorical variables’ Year’ for 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 were included with 2019 as the reference. We obtained a significant negative association for these variables with API, AFI and AVI for both the central and northern regions, reflecting a decrease in cases. However, a significant positive association was shown with API in 2023 and with AVI in 2020, 2021 and 2022 for the northeast region. Thus, our model could capture the increase in AVI in the north-eastern region, as also observed in Fig. 2. The estimated ORs for the districts reporting API, AFI and AVI = 0 are provided in the supplementary. Overall, the models reported MSEs < 0.3 for AVI, between 0.15 and 2.6 for API and < 1.9 for AFI, thus indicating the suitability of the models. The odds ratio for districts reporting zero transmission is provided in the supplementary as Figure S5, which is obtained from logistic component of the ZIP model. The model identified the dual effect of the covariates separately in districts reporting non-zero and zero transmission.

Dashboard

Our ‘MIDAS’ dashboard provides the spatiotemporal mapping of malaria indicators for all districts between 2019 and 2023. On the left panel, the user can choose between spatial and temporal variations. For both, there are dropdown menus through which a user can select the year and the parameters of interest. After initialisation, the spatial maps and temporal plots are generated. Using the mouse, the data for all districts can be viewed. The temporal maps provide the annual change in the malaria parameters for each district. The snapshot for the dashboard is provided in Fig. 5, while the detailed Standard Operating Procedure is provided as supplementary material 2. The screenshots of the main page, left panels and outputs are depicted in the Figures S2.1, S2.2, S2.3, S2.4, S2.5, S2.6, S2.7, S2.8 and S2.9.

Summary for general public and stakeholders

Our work identified three distinct regions of increased malaria transmission; central, north and north-east India. Cases due to the P. vivax have decreased in the northern districts, but they have increased in the northeastern India after the COVID-19 pandemic. The cause of this increase is not clear, as cases due to P. falciparum are prevalent in both northeastern and central districts. Our modelling results indicate that drinking water practices related to collection and storage is a concern as these practices could led to potential breeding sites for Anopheles mosquito. Forested and inundated agricultural land should be continuously monitored as they emerged as risk factors in all three regions. We also identified that socioeconomically marginalised population and those who continue to live in muddy houses are at high risk of malaria. However, the path to eliminate malaria can be aided by improving health care accessibility and focusing on education of mothers along with concerted focus on socioeconomic development. We recommend the policymakers to consider including the variables during their routine large-scale data collection to assess the risk for different sections of the vulnerable population. The digital dashboard developed here, can also be integrated with real-time data which can be used with the socioeconomic and weather data for real-time risk monitoring. Moreover, the general public should also be informed about the changing patterns in malaria and common prevention methods through social and print media. The main findings are summarized in Fig. 6.

Conclusions

Through this work, we map the spatiotemporal distributions of malaria indicators between 2019 and 2023. We observe that malaria has reduced in the last five years, compared to the previous decades, although there is a marginal increase in 2023 when compared to 2022. The significant hotspots for API, AVI and AFI are concentrated in Central India and North-eastern India; however, the clusters for AVI were also found in the northern states of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. A geographical expansion in the clusters for AVI is observed in Northeast India throughout the years. This unprecedented increase in P. vivax has been confirmed microscopically and molecularly at subcentre and village spatial levels (Unpublished Data). Our region-specific spatiotemporal models for each indicator suggest that while economically marginalised communities continue to be the most vulnerable sections, drinking water practices, maternal education, and healthcare accessibility are associated with the transmission. We believe that simple behavioural changes in the population, such as periodic overhead water tank cleaning or adopting ITNs and a healthy lifestyle, could reduce the malaria burden. Our dashboard is expected to raise awareness among the general public and help the stakeholders involved in malaria control in tracking the malaria indicators over the years. Our study uses annual data, where the true impact of seasonality cannot be measured. Further, while the ecological study design is helpful in assessing the population-level patterns, the risks reported here should be reassessed through cross-sectional or longitudinal study designs to avoid potential bias, although similar associations have been reported elsewhere. The true impact of seasonality and delayed impact of the meteorological variables can only be assessed through more detailed temporal data at weekly or monthly scales. Further, integrating real-time data on malaria parameters and modelling outputs into the dashboard would enhance risk assessment and provide valuable support to all stakeholders. We also recommend to the stakeholders to include the identified variables during data collection on reported/suspected malaria cases. Future work should also focus on longer temporal data to assess the impact of weather variables. We hope that our study will help the stakeholders and generate awareness among the general public of the country. Let’s end malaria once and for all together!

Data availability

The study utilised publicly accessible data from NCVBDC. However, the curated data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, H.C.P., upon request.

References

Kumari, R., Kumar, A., Dhingra, N. & Sharma, S. N. Transition of malaria control to malaria elimination in India. J. Commun. Dis. 54, 124–140 (2022).

Rahi, M. & Sharma, A. Malaria control initiatives that have the potential to be gamechangers in India’s quest for malaria elimination. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast. Asia 2, 100009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.04.005 (2022).

Sam, A. K., Karmakar, S., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Phuleria, H. C. A historical perspective of malaria policy and control in India. IJID Reg. 12, 100428. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJREGI.2024.100428 (2024).

World Health Organisation. World Malaria Report 2024. https ://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024 (2024).

World Health Organization. Global Malaria Programme Operational Strategy 2024–2030 01–84 (2024).

Odhiambo, J. N., Kalinda, C., MacHaria, P. M., Snow, R. W. & Sartorius, B. Spatial and spatio-temporal methods for mapping malaria risk: a systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 5(10), 2919. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2020-002919 (2020).

Snow, R. W., Marsh, K. & Le Sueur, D. The need for maps of transmission intensity to guide malaria control in Africa. Parasitol. Today. 12 (12), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(96)30032-X (1996).

Snow, R. W. & Noor, A. M. Malaria Risk Mapping in Africa The Historical Context to the Information for Malaria (INFORM) Project (2015).

Kraemer, M. U. G. et al. Progress and challenges in infectious disease cartography. Trends Parasitol. 32 (1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PT.2015.09.006 (2016).

Ye, Y. & Andrada, A. Estimating malaria incidence through modeling is a good academic Exercise, but how practical is it in High-Burden settings? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102 (4), 701–702. https://doi.org/10.4269/AJTMH.20-0120 (2020).

Wimberly, M. C., de Beurs, K. M., Loboda, T. V. & Pan, W. K. Satellite observations and malaria: new opportunities for research and applications. Trends Parasitol. 37 (6), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PT.2021.03.003/ATTACHMENT/A6F80937-DD23-43E2-B10A-3606AAC53BB1/MMC1.DOCX (2021).

Sarkar, S., Singh, P., Lingala, M. A. L., Verma, P. & Dhiman, R. C. Malaria risk map for India based on climate, ecology and geographical modelling. Geospat. Health 14(2), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2019.767 (2019).

Kumar, G. et al. Mapping malaria vectors and insecticide resistance in a high-endemic district of Haryana, india: implications for vector control strategies. Malar. J. 23 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-023-04797-8/TABLES/5 (2024).

Sarkar, A. et al. Spatial Analysis and Mapping of Malaria Risk in Dehradun City India: A Geospatial Technology-Based Decision-Making Tool for Planning and Management 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2097-6_14 (2020).

Singh, P., Lingala, M. A. L., Sarkar, S. & Dhiman, R. C. Mapping of malaria vectors at district level in India: changing scenario and identified gaps. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 17(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1089/VBZ.2016.2018 (2017).

Sam, A. K., Khatoon, A. & Phuleria, H. C. Determinants of malaria transmission in Indian districts in 2018: insights from ensemble models. Malar. J. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-025-05546-9 (2025).

Ministry of Space & Technology. Survey of India. https://onlinemaps.surveyofindia.gov.in/Digital_Product_Show.aspx (2025).

Van den Bossche, J. et al. geopandas/geopandas: v1.0.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.12625316 (n.d.).

Getis, A. & Ord, J. K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 24(3), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1538-4632.1992.TB00261.X (1992).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30(14), 5419–5454. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Karra, K. et al. Global land use/land cover with sentinel 2 and deep learning. International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2021-July 4704–4707. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS47720.2021.9553499 (2021).

Plotly Technologies Inc. Collaborative Data Science (Plotly Technologies Inc, 2015).

Yadav, C. P. & Sharma, A. National Institute of Malaria Research-Malaria Dashboard (NIMR-MDB): A digital platform for analysis and visualisation of epidemiological data. Lancet Reg. HealthSoutheast Asia 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100030 (2022).

Reback, J. et al. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas 1.0.5. Zndo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.3898987 (2020).

Jordahl, K. et al. geopandas/geopandas: v0.5.0. Zndo. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.2705946 (n.d.).

Wyss, K. et al. Obesity and diabetes as risk factors for severe plasmodium falciparum malaria: results from a Swedish nationwide study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65 (6), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1093/CID/CIX437 (2017).

Kojom Foko, L. P., Nolla, N. P., Nyabeyeu, N., Tonga, H. & Lehman, L. G. Prevalence, patterns, and determinants of malaria and malnutrition in Douala, cameroon: A cross-sectional community-based study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021(1), 5553344. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5553344 (2021).

Franco, A. O., Gomes, M. G. M., Rowland, M., Coleman, P. G. & Davies, C. R. Controlling malaria using livestock-based interventions: A one health approach. PLoS ONE 9(7), e101699. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0101699 (2014).

Hasyim, H. et al. Does livestock protect from malaria or facilitate malaria prevalence? A cross-sectional study in endemic rural areas of Indonesia. Malar. J. 17 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-018-2447-6/TABLES/2 (2018).

Mayagaya, V. S. et al. The impact of livestock on the abundance, resting behaviour and sporozoite rate of malaria vectors in Southern Tanzania. Malar. J. 14 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-014-0536-8/TABLES/4 (2015).

Njau, J. D., Stephenson, R., Menon, M. P., Kachur, S. P. & McFarland, D. A. Investigating the important correlates of maternal education and childhood malaria infections. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91 (3), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.4269/AJTMH.13-0713 (2014).

Thomas, T. K. Role of health insurance in enabling universal health coverage in India: A critical review. Health Serv. Manage. Res. 29(4), 99–106 (2016).

Yadav, K., Dhiman, S., Rabha, B., Saikia, P. K. & Veer, V. Socio-economic determinants for malaria transmission risk in an endemic primary health centre in Assam, India. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 3 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9957-3-19/TABLES/3 (2014).

Yang, D. et al. Drinking water and sanitation conditions are associated with the risk of malaria among children under five years old in sub-Saharan africa: A logistic regression model analysis of National survey data. J. Adv. Res. 21, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JARE.2019.09.001 (2020).

Sharma, R. K. et al. Socio-economic determinants of malaria in tribal dominated Mandla district enrolled in malaria elimination demonstration project in Madhya Pradesh. Malar. J. 20 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-020-03540-X/TABLES/4 (2021).

Mandal, B. et al. Breeding propensity of Anopheles stephensi in chlorinated and rainwater containers in Kolkata City, India. J. Vector Borne Dis. 48, 58–60 (2011).

Kamal, S., Chandra, R., Mittra, K. K. & Sharma, S. N. An investigation into outbreak of malaria in Bareilly district of Uttar Pradesh, India. J. Commun. Dis. 52 (4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.24321/0019.5138.202034 (2020).

Ahmed, S., Reithinger, R., Kaptoge, S. K. & Ngondi, J. M. Travel is a key risk factor for malaria transmission in pre-elimination settings in Sub-Saharan africa: A review of the literature and meta-analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 103(4), 1380. https://doi.org/10.4269/AJTMH.18-0456 (2020).

Minale, A. S. & Alemu, K. Mapping malaria risk using geographic information systems and remote sensing: the case of Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. Geospat. Health 13(1), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2018.660 (2018).

Shayo, F. K., Nakamura, K., Al-Sobaihi, S. & Seino, K. Is the source of domestic water associated with the risk of malaria infection? Spatial variability and a mixed-effects multilevel analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 104, 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJID.2020.12.062 (2021).

Obembe, A., Popoola, K. O. K., Oduola, A. O. & Awolola, S. T. Differential behaviour of endophilic Anopheles mosquitoes in rooms occupied by tobacco smokers and non-smokers in two Nigerian villages. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 22(6), 981–985. https://doi.org/10.4314/JASEM.V22I6.23 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Centre for Vector Borne Disease Control Programme for the malaria data, the Indian Institute for Population Science and the Demographic and Health Survey for the National Family Health Survey data, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the meteorological data. The authors thank Dr. Tanu Jain (Director, NCVBDC), Dr. Pranab Jyoti Bhuyan (Additional Director, NCVBDC) and the malaria team at the NCVBDC for their valuable insights. The work is based on research findings by the authors and not the opinion of the government.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Gates Foundation (NV-044445). AS wants to thank the Ministry of Education for providing the Prime Minister Research Fellowship (ID-1302077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Avik Kumar Sam, AS: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, visualisation, validation, writing- original draftNeha Keshri, NK: Formal analysis, visualisation, writing- original draftIpsita Pal Bhowmick, IPB: Validation, writing-review & editingAnup Anvikar, AA: Writing-review & editingHarish C. Phuleria: Conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing-review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sam, A.K., Keshri, N., Bhowmick, I.P. et al. Mapping malaria risk in India between 2019 and 2023: a tool for the public to track malaria. Sci Rep 15, 42956 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25671-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25671-4