Abstract

To understand the crack propagation and chip formation mechanism caused by a PDC bit for various gravity values, a numerical study using particle flow code in 2 dimensions (PFC 2D) is performed. The numerical results indicate that the cracks, caused by stress concentrations, are responsible for chip formation. In addition, the fracture area and cutting efficiency first increase and then decrease with the increase in gravity. The dynamic analysis of stress evolution in the cutting process indicates that the input energy per step curve consists of many fluctuations, accompanying with crack propagation and stress concentration-dissipation cycles. Moreover, the theoretical analysis using the maximum circumferential stress theory successfully explains the reason why the increase in gravity first increases and then decreases the fracture area and cutting efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extraterrestrial planets may harbor abundant mineral resources, including silicates, oxides, sulfides, and native metals1. In addition, the terrestrial mineral resources gradually deplete. Thus, the exploitation of extraterrestrial planets resources is a promising frontier and a new research focus with the rapid development of human technology2. To successfully utilize these mineral resources, the efficient breakage of these extraterrestrial rocks is fundamental. Polycrystalline diamond compact (PDC) bits and disc cutters are common rock breakage tools. Especially, PDC bits have been widely used in resource exploration process3. For instance, resource exploration with PDC bit has been used since 1970’s4. In addition, PDC bits can be used to break different kinds of hard-to-drill lithologies5. Thus, PDC bits may be efficient rock cutting tools at the early exploration stage of extraterrestrial planets. In the cutting process of PDC bits, stress concentrations firstly form in the rock. Then, when these stresses exceed critical values, cracks initiate and propagate. The crack propagation directly determines rock chip formation and further affects the cutting efficiency. Previous studies indicated that many factors including cutter shape6,7, cutting rate8, cutting depth9, etc., significantly influence this rock chip process. For example, the cross sectional area of groove, correlated to the bit shape, directly influences the cutting force6. In addition, torsional impact cutting instead of steady loading frequently results in smaller cutting forces7. Moreover, the cutting distance promotes the cutting depth of the PDC cutter9.

The vacuum environment, large temperature change, radiation and gravity variation of the extraterrestrial planets may may result in the differences in mechanical properties of the extraterrestrial particle media including soils and rocks10,11,12. Especially, the gravity directly affects the formation of the particle media and further determines the stress distribution in the particle media13. Previous studies indicated that gravity significantly affects the mechanical response of the extraterrestrial soil to the external loads14,15. However, the effects of gravity on rock breakages lack detailed studies.

To generate extraterrestrial conditions on the earth may be costly and unavailable for most researchers16. Instead, the discrete element method (DEM) is more efficient in simulating extraterrestrial conditions14,15,16. Thus, in the present study, particle flow code in two dimensions (PFC 2D) is applied to study the influence of gravity on dynamic fracture process of extraterrestrial rock. The load transition law and the energy consumption in the cutting process are also discussed.

Numerical model

Introduction to PFC 2D

Previous studies indicated that the discrete element method is applicable to simulate the mechanical properties of extraterrestrial media19,20. In PFC 2D models, parallel bonds connect adjacent particles (widely used to simulate rock materials)21,22 are adopted. In addition, this contact bond model has been successfully used to simulate extraterrestrial rock specimens19. External loads may cause shear or tensile stress concentrations in these bonds (Fig. 1a). When either of these stresses exceeds the bond strength, including the shear strength (\(\overline {{{\tau _c}}}\)) and the tensile strength (\(\overline {{{\sigma _c}}}\)), a micro crack generates (Fig. 1b). The accumulation of these micro cracks can result in the macro failure of the specimen.

Numerical model

Before simulating the cutting process of PDC bits, the calibration of rock samples is essential. In PFC simulations, the uniaxial compressive stress-strain curve is frequently calibrated23. The previous study indicated that the penetration hardness of a typical extraterrestrial rock is 1080 MPa24. According to the previous study on the relation between the uniaxial compression strength and the penetration hardness25, the unixial compressive strength in the present study is 85.7 MPa. Figure 2a shows the calibrated uniaxial compressive strength and the failure sample when the gravity is 9.8 m/s2. Clearly, the uniaxial compressive strength is close to the reported value. Table 1 lists the micro parameters of the rock specimen.

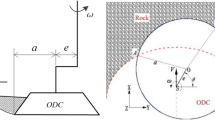

Figure 2b shows the cutting model of the PDC bit. The width and height of the rock specimen are close to the previous study8. The inclination angle of the PDC bit is 20°26. The adopted values of the gravity in the present study are 1.6 m/s2, 5.7 m/s2, 9.8m/s2 and 12.9 m/s2. The cutting depths are 1 mm, 2 mm and 3mm. To save the calculation time, the advance rate of the bit and the advance distance are 2 m/s8 and 2.4 mm. In the cutting process, the right and bottom boundaries are fixed. Simultaneously, the input boundary energy (Eq. 2) is dynamically recorded27.

Where Eb, Fwall and xwall are the boundary work, bit force and bit displacement, respectively.

To investigate the relation between input energy and crack propagation in the cutting process, measure circle logic is applied. 5100 overlapping measure circles with a radius of 0.3 mm entirely cover the rock specimen (Fig. 2b). These measure circles can record the horizontal stress, σxx, the vertical stress, σyy and the shear stress, τxy28. Thus, the principal stresses (σmax and σmin ) can be calculated:

Results

To evaluate cutting efficiency, specific energy (SE), widely used in previous studies, is a critical index29,30.

Where E and A are the consumed energy and the fracture area, respectively.

The SE value represents the the energy for breaking unit rock. Clearly, a lower SE represents the higher cutting efficiency. The following sections mainly focus on rock fracture and the consumed energy.

Rock fractures

Figure 3 shows the rock fractures for different gravity values and cutting depths. When the gravity and the cutting depth are 1.6 m/s2 and 1 mm, respectively, Fig. 3a1 clearly shows that the fracture area is limited. A crack failing to from rock chips generates. When the cutting depth increases to 2 mm, the fractured area expands Fig. 3a2. With the further increase in cutting depth to 3 mm, Fig. 3a3 shows that the fracture area further expands. Similarly, a crack failing to from rock chips appears. For the other gravity values, we may infer that the increase in cutting depth increases the fracture area, as shown in Fig. 3. This inference can be firmly confirmed by Fig. 4 and the previous studies26,31. When the gravity increases to 5.7 m/s2, Fig. 3b1 shows that the fracture area expands. The crack propagating to the top surface is responsible for this rock chip. As represented in Fig. 3c1,a smaller rock chip forms for the gravity of 9.8 m/s2 However, rock chips fail to form when the gravity increase to 12. 9 m/s2. Thus, the fracture area decreases. For the other cutting depths, referring to Figs. 3 and 4, it is evident that the fracture area also first increases and then decreases with the increase in gravity. The above analysis indicate that rock fractures are commonly caused by cracks propagating to the top surface. In addition, the effect of gravity on crack propagation is significant and needs further study.

Rock fractures (a1–d1) are rock fractures when the cutting depth is 1 mm for the gravity of 1.6 m/s2, 5.7 m/s2, 9.8 m/s2 and 12.9 m/s2; (a2–d2) are rock fractures when the cutting depth is 2 mm for the gravity of 1.6 m/s2, 5.7 m/s2, 9.8 m/s2 and 12.9 m/s2; (a3–d3) are rock fractures when the cutting depth is 3 mm for the gravity of 1.6 m/s2, 5.7 m/s2, 9.8 m/s2 and 12.9 m/s2.

Input energy

Figure 5 depict the input energy per step for various gravity values. Figure 5a clearly shows that the input energy per step fluctuates with the increase in cutting distance for the gravity value of 1.6 m/s2. This phenomenon agrees well with the previous cutting force-distance curves19,26. More importantly, the average and peak values of the input energy per step increases with the increase in cutting depth. Thus, Fig. 6 shows that the increase in cutting depth results in the promoted consumed energy, obtained by accumulating the input energy per step. Figure 5b–d indicate that similar results are observed for the other gravity values. Thus, we can conclude that the increase in cutting depth promotes the consumed energy for various gravity values. However, the effect of gravity on the consumed energy for the same cutting depth is unclear (Fig. 6). In addition, the input energy curve per step consists of many fluctuations. These fluctuations may correlate with rock fractures and are discussed in the following section.

Using Eq. 4 and the data in Figs. 4, 6 and 7 shows the specific energy for various gravity values. The fitted curves clearly shows that the SE first decreased and then increased with the increase in gravity. In other words, the increase in gravity first promotes and then restrains the cutting efficiency for the specific cutting depth. The effect of gravity on rock fractures is responsible for this result (Fig. 4). However, for the same gravity, the effect of cutting depth on cutting efficiency is irregular.

Discussions

The above analysis show that the fracture area determines the cutting efficiency. The rock fracture (crack propagation) strongly correlates with cutting load (input energy)32,33, thus, the following section discusses dynamic crack propagation process and the effect of gravity on crack propagation.

The dynamic fracture process

Figure 8 depicts the typical input energy curve for the gravity and cutting depth of 9.8 m/s2 and 3 mm, respectively. This curve consists of many fluctuations. In the present study, two typical fluctuations (P1-B1 and P2-B2) are investigated. At P1 point, a peak value of input energy per step appears. Figure 9a indicates that small fractures near the contact point between the rock and the PDC bit form. A highly shear stress concentrated zone covers this fracture area. In addition, a tensile stress concentration zone appears beneath this shear stress concentration zone. When the cutting distance increases to about 0.32 mm, a bottom point (B1) appears. At this point, the fracture area expands. More importantly, shear and tensile stress concentrations simultaneously dissipate (Fig. 9b). Clearly, the stress concentrations are responsible for the fracture area expansion. Similar fracture expansion by stress concentrations has been reported in the previous study28. Similarly, the fluctuations before P1-B1 fluctuation may be responsible for the formation of the small fracture area in Fig. 9a. For the P2-B2 fluctuation, the PDC bit advance results in tensile and shear stress concentrations. Especially, tensile stress concentrates at crack tips (Fig. 10a). When the cutting distance reaches about 1.05 mm, shear stress concentrations disappear. In addition, tensile stress concentrations at crack tips significantly dissipate(Fig. 10b). The above analysis clearly indicates that the advance of the PDC bit first cause stress concentrations in rock. When the stresses reach critical values, cracks, causing fractures, propagate. Simultaneously, these stress concentrations dissipate. For the other fluctuations, similar crack propagations accompanying with stress concentration-dissipation are also observed (figures not shown). Thus, we can conclude that the fluctuations of the input energy per step frequently accompany with crack propagation and stress concentration-dissipation cycles.

The effect of gravity on fracture propagation

The above sections show that crack propagation is critical for chip formation. In addition, the stress concentrations are responsible for crack propagation causing rock fractures. Moreover, crack propagation path also directly influences the rock fracture degree. Therefore, the following section mainly discuss the effect of gravity on crack propagation direction, using the maximum circumferential stress theory.

In the present study, the crack propagation caused by PDC bit is the Mode I-II combined crack propagation. Figure 11a shows the stresses at the internal crack tip33,34:

Where σθθ, r, θ, τrθ, KI and KII are the radial stress, the expansion radius, the fracture angle, the circumferential stress, the shear stress, the Mode I stress intensity and the Mode II stress intensity, respectively. According to the maximum circumferential stress theory, cracks initiate when:

In addition, the direction of the minimum principal stress indicates the crack propagation direction. In the present study, the angle between the minimum principal stress and the X axis (α) is defined as the crack angle (Fig. 11b). If the minimum principal stress direction rotates with a counterclockwise angle to overlap with X axis, the value of α (Eq. 8) is positive. On the contrary, the value of α is negative33.

Using the recorded stresses in measure circles and Eq. 8, Fig. 12a1 shows three monitor points (#1 P, #2 P and #3 P) at P2 point (Fig. 8). According to the maximum circumferential stress theory, as illustrated in Fig. 12a2 ,it shows that the predicted crack angle at these points are − 19.4°, -4.5°and 39.7°.Clearly, these data predicted crack angle are close to the measured crack angles in Fig. 12b1. Figure 12b2 shows that the predicted crack angles are − 2.4°and − 3.8°at #4P and #5P. These predicted crack angles are also close to the following measured crack angles, as depicted in Fig. 3c3. The irregularly distributed particles are responsible for the small differences between the predicted and the measured crack angles. The above comparison between the predicted crack angles and the measured crack angles firmly indicate that the crack propagation caused by PDC bit obeys the maximum circumferential stress criterion.

To investigate the influence of gravity on crack propagation, Fig. 13a plots the average crack angles for different gravity values and cutting depth. Clearly, the effect of cutting depth on crack angle is irregular. However, the increase in gravity values obviously promotes the crack angle. For the small gravity value, according to Fig. 13b, the negative crack angles frequently form small rock chips at the shallow part. With the increase in crack angle, larger chips may form. However, with the further increase in crack angle, the crack may fail to form rock chips. Thus, the increase in crack angle first promotes and then restrains rock fractures. In accordance with Fig. 4, this phenomenon can properly verify why the increase in gravity first increases and the decreases the fracture area for the same cutting depth. In addition, the reason why the cutting efficiency first increases and then decreases with the increase in gravity can also be explained (Fig. 7).

Conclusions

To study the effect of gravity on rock fracture by PDC bit, a 2D numerical study based on discrete element method is performed. The numerical simulation indicates that the increase in gravity first increase and then decrease the fracture area. However, the effect of gravity on the consumed energy for the same cutting depth is limited. Thus, the cutting efficiency first increases and then decreases with the increase in gravity, ranging from 1.6 m/s2 to 12.9 m/s2. In addition, the dynamic monitoring of the stress field in the cutting process shows that the increase in input energy per step frequently cause stress concentrations. When the stress reaches critical values, cracks propagate and form rock fractures. In the crack propagation process, stresses dissipate. Moreover, the crack propagation obeys the maximum principal stress criterion. The predicted crack angles indicate that the increase in gravity frequently promotes crack angles. This increase in crack angle first increase and then decrease the rock fracture area.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bell, L. Top-level considerations for planning lunar/planetary habitat structures. J. Aerospace Eng. 24 (3), 349–360 (2010).

Zhou Guoqing, L. I., Ruilin, Y. A. N. & Kang Theoretical and experimental methods for lunar regolith/ rock related mechanical issues in lunar minerals mining. J. China Coal Soc. 44 (1), 183–191 (2019). (in Chinese).

Liu, W. & Gao, D. Research status and development trends of polycrystalline diamond compact Bits. Sci. Technol. Foresight 168–178. (2023).

Rostamsowlat, I., Akbari, B. & Evans, B. Analysis of rock cutting process with a blunt PDC cutter under different wear flat inclination angles. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 171, 771–783 (2018).

Liao, Q. et al. Study on different kinds of drill Bits and their usage in hard-to-drill formations. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils. 59, 783–790 (2023).

Doshvarpassand, S. & Richrd, T. Mostofi,.M. Effect of groove geometry and cutting edge in rock cutting. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 151, 1–12 (2017).

Zhu, X., Luo, Y. & Liu, W. The rock breaking and ROP increase mechanisms for single-tooth torsional impact cutting using DEM. Petrol. Sci. 1–14. (2019).

Zhu, X., Wang, Y. & Liu, W. The rock-breaking performance of the special-shaped PDC cutter under combined penetration and cutting. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. (2024).

Wei, J. W., Liu, D. & Gao Modeling of PDC bit-rock interaction behaviors based on the analysis of dynamic rock-cutting process. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. (2024).

LI, R., ZHOU, G. & HALL, M. R. Micro-mechanical behaviour of granular materials under gravity-induced stress gradient. Granul. Matter. 20 (3), 53 (2018).

LI, R., ZHOU, G. & HALL, M. R. Arching effect of planetary regolith simulant under extraterrestrial gravities. J. Aerospace Eng. 31 (6), 04018097 (2018).

NOWATZKI E A & Earth The effect of a thermal and ultrahigh vacuum environment on the strength of precompressed granular materials. Moon Planet. 5 (1), 31–40 (1972).

LI Ruilin. Mechanical behaviour of granular matter under gravity-induced stress gradient. China Univ. Min. Technol. 45–110 (2018).

Tianxi Liu, J., Zhou, L., Liang, Y., Zhao, D. & Cao A novel torque analysis method for drilling deep lunar soil by DEM. J. Terrramech. 94, 23–37 (2021).

Mingjing Jiang, F., Liu, Z., Shen, M. & Zheng Distinct element simulation of lugged wheel performance under extraterrestrial environmental effects. Acta Astronaut. 99, 37–51 (2014).

Jiang, M., Dai, Y., Cui, L. & Xi, B. Experimental and DEM analyses on wheel-soil interaction. J. Terrramech. 76, 15–28 (2018).

Tianxi Liu, J., Zhou, L., Liang, Y., Zhao, D. & Cao Investigation of effect of stones on lunar regolith drilling using DEM. Comput. Geotech. 131, 103958 (2021).

Liu, T., Liang, L., Zhao, Y. & Cao, D. Equivalent boundary model of lunar soil drilling simulation by DEM. J. Terrramech. 91, 85–95 (2020).

Li, P., Jiang, S., Tang, D. & Xu, B. A PFC3D-based numerical simulation of cutting load for lunar rock simulant and experimental validation. Adv. Space Res. 59, 2583–2599 (2017).

Mingjing Jiang, T., Zhao, X. & Wang DEM modelling of cone penetration tests in lunar soil. Granul. Matter. 24, 5 (2022).

Ri-hong Cao, P., Cao, H., Lin, C., Pu & Ou, K. Mechanical behavior of brittle rock-like specimens with pre-existing fissures under uniaxial loading: experimental studies and particle mechanics approach. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 763–783. (2015).

Ri-hong Cao, P., Cao, X., Fan, X., Xiong & Lin, H. An experimental and numerical study on mechanical behavior of Ubiquitous-Joint brittle Rock-Like specimens under uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49, 4319–4338 (2016).

Wang, M., Lu, Z. X., Zhao, Y. L. & Wan, W. A calibration framework for DEM models based on the stress-strain curve of uniaxial compressive tests by using the AEO algorithm and several calibration suggestions. Comput. Particle Mech. (2024).

Yizhuo, W. A. N. G., Peng, L. I., Lixia, S. U. N., Xuesong, L. I. & Hongyang, N. I. N. G. Design and test verification of test platform for simulating low-force cutting load characteristics of lunar rock. J. Beihua Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 22, 408–414 (2022).

Hua, C. H. E. N. G., Xiaoyun, W. A. N. G., Zhishu, Y. A. O., Longhui, G. U. O. & Jian, L. I. N. Drillability classification method of Jurassic strata in drilling method based on rock breaking specific energy. J. Min. Saf. Eng. (2024).

Xi, Y. et al. Numerical simulation of rock-breaking and influence laws of dynamic load parameters during axial-torsional coupled impact drilling with a single PDC cutter. Pet. Sci. 20, 1806–1827 (2023).

Tai, D. P. et al. Shear mechanical properties and energy evolution of rock-like samples containing multiple combinations of non-persistent joints. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 15, 1651–1670 (2023).

Liu, J., Wang, J. & Wan, W. Numerical study of crack propagation in an indented rock specimen. Comput. Geotech. 96, 1–11 (2018).

Zhang, X., Tan, T., Li, M. & Liao, Y. Yanchao Tian, and jingping Liao, ‘Research on rock breaking behaviors of different Tbm hobs under grooving condition produced by water jet’. Eng. Fail. Anal. 162, 108373 (2024).

Zhang, K., Liu, Q. & Zhang, Z. Simulation of rock breaking based on Fem-Czm method and its application in disc cutter parameter optimization. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27, 384–398 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Zhao, D., Zhao, Y., Gao, K. & Zhang, C. Xiaoshu Lü. 3D numerical simulation study of rock breaking of the wavy PDC cutter and field verification. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 203, 108578 (2021).

Jie Liu, B. et al. Promoted cutting and energy transition efficiency by an asymmetric cutter. Eng. Fract. Mech. 311, 110599 (2024).

Jie, L. et al. Rock breakages caused by an asymmetric cutter and a constant cross-section cutter acting on precuts. Archives Civil Mech. Eng. 25, 100 (2025).

Zhao, K. K., Jiang, P. F. & Feng, Y. J. Investigation of the characteristics of hydraulic fracture initiation by using maximum tangential stress criterion. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 3 (2), 14–22 (2021). (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52175254); Hunan Provincial Innovation Foundation For Postgraduate (CX20230550.CX20240614).

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52175254) and Hunan Provincial Innovation Foundation For Postgraduate (CX20230550 and CX20240614).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qiaolong Zhang, Youhang Zhou and Yanhong Su wrote the main text, Tianyu Gong and Ding Li prepared the figures and Youhang Zhou and Yaqian Tang review the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Q., Zhou, Y., Su, Y. et al. The effects of gravity on rock fractures caused by PDC bits. Sci Rep 15, 41795 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25695-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25695-w