Abstract

Finger millet productivity is strongly influenced by genotype × environment interaction (GEI), which complicates the identification of high-yielding and stable genotypes. This study evaluated 35 genetically diverse finger millet genotypes across three agro-ecological zones viz., Odisha (E1), Jharkhand (E2), and Bihar (E3) during two rabi seasons (2023–24 and 2024–25). A randomized block design with three replications was implemented and key quantitative traits i.e. grain yield per plant, 1000-grain weight, and number of fingers on the main ear were recorded. AMMI and GGE biplot analyses were applied to assess GEI, stability, and adaptability. Genotype G18 (VR-1176) consistently emerged as the most stable and high-yielding across environments, followed by G13 (VL-Mandia-352), G28 (Bada Mandia), G3 (PR-1639), G25 (Bada Kumnda), G26 (Badatara), G11 (VR-1223), G15 (VR-12-38), G14 (OEB-610), and G33 (FEZN-84). AMMI 1 and AMMI 2 biplots confirmed these findings, highlighting G18 and G15 as superior performers. Among sites, Jharkhand (E2) was identified as the most favourable environment. Additionally, molecular profiling using UGEP markers 46, 66, and 68 revealed polymorphic banding in high-yielding genotypes, which validates phenotypic observations. The integration of phenotypic and molecular analyses provides a robust framework for identifying finger millet genotypes with both high productivity and yield stability, supporting their recommendation for breeding programs and wider cultivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Finger millet (Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.) is a self-pollinated cereal crop belonging to the family Poaceae and subfamily Chloridoideae. It is a tetraploid species with a genome composition of 2n = 4x = 36 and is classified under the genus Eleusine1. This crop is believed to have originated in the Ethiopian highlands and has been cultivated for centuries across East Africa and the Indian subcontinent. At present, it is extensively grown in countries such as India, Nepal, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya. It is commonly known as “ragi” in India, “dagussa” in Ethiopia, and “wimbi” in Kenya. Owing to its remarkable adaptability and rich nutritional profile, finger millet is recognized as a “Smart Food” crop for modern agriculture and human nutrition2,3. Finger millet is highly suited to low-input farming systems and performs exceptionally well under marginal, rainfed conditions. It exhibits remarkable ecological adaptability, flourishing at elevations up to 2400 m, in nutrient-deficient soils, and under erratic rainfall patterns. These resilient traits make it an ideal crop for cultivation in drought-prone areas. From a nutritional standpoint, finger millet is a rich source of both macronutrients and micronutrients, containing approximately 65–75% carbohydrates, 6–13% protein, 15–20% dietary fiber and only 1.3–1.8% fat4,5. A distinguishing feature of this crop is its exceptionally high calcium concentration (≈ 344 mg per 100 g), nearly tenfold higher than that of major cereals such as rice and wheat. It also contains appreciable levels of iron, phosphorus, and essential amino acids, including methionine and lysine6,7. These nutritional attributes make finger millet particularly beneficial for vulnerable groups such as infants, pregnant women, the elderly and individuals with diabetes, owing to its low glycemic index and high nutrient density8. Beyond grain, the straw serves as a valuable source of livestock fodder, while the crop itself contributes positively to soil health and sustainable farming systems.

India is the world’s leading producer of finger millet, contributing over 60% of global output. The principal finger millet-growing states include Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Odisha and Uttarakhand9. Under favourable conditions, yields can reach up to 4.0 t ha⁻¹; however, in rainfed systems, average productivity typically ranges between 1.0 and 1.5 t ha⁻¹10. This yield gap is primarily due to the continued use of traditional landraces, minimal application of external inputs, and the crop’s predominant cultivation as a subsistence or intercrop. Further production expansion is hindered by limited research investment, a shortage of improved cultivars, weak seed distribution channels and poorly developed market support systems11.

Despite its agronomic and nutritional advantages, the broader adoption of finger millet is constrained by inconsistent grain yield performance across diverse agro-ecological regions. This variability is primarily driven by genotype × environment interaction (GEI), whereby genotypes exhibit differential responses to variations in climate, soil properties and management practices12. Multi-environment trials (METs) are therefore essential for identifying genotypes that combine high yield potential with stability across locations.

Traditionally, analysis of variance (ANOVA) has been employed to partition the variation attributable to genotypes, environments and their interactions. However, ANOVA treats GEI as part of the residual variance, providing little insight into the underlying interaction study13. To overcome these limitations, a range of stability assessment methods have been developed, spanning both univariate and multivariate statistical approaches. Among these, multivariate techniques such as cluster analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) have been particularly effective in revealing the structure of GEI and identifying genotypes with consistent performance14.

Graphical tools such as biplots further enhance GEI analysis by providing an intuitive visualization of the relationships among genotypes, environments and their interactions. PCA-based biplots are particularly useful for distinguishing between genotypes with broad versus specific adaptation and for evaluating the representativeness and discriminative ability of test environments15. Two of the most widely adopted models in this regard are the Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI) model and the Genotype plus Genotype × Environment (GGE) biplot. The AMMI model integrates ANOVA and PCA, employing singular value decomposition (SVD) to partition GEI and generate informative biplots (AMMI1 and AMMI2)16. By separating the additive effects of genotypes and environments from their interactions, AMMI facilitates the identification of stable and widely adapted genotypes. In contrast, the GGE biplot emphasizes the combined effects of genotype and GEI (G + GE), excluding the main environmental effect. This framework is particularly effective for identifying “which-won-where” study, delineating mega-environments and selecting both ideal genotypes and representative test environments17. The GGE approach has proven especially valuable for cultivar recommendation across diverse agro-ecological regions. Previous studies, particularly in Ethiopia, have successfully applied AMMI and GGE biplot analyses to finger millet, identifying stable and high-yielding lines such as Acc. 203,54418. While these models have also been widely used in cereals like wheat, oats and pearl millet, their combined application to finger millet within Indian agro-ecological systems remains limited. This underlines the need for integrated GEI studies in the Indian context.

The present study aims to assess yield performance and stability of diverse finger millet genotypes across multiple environments in India using both AMMI and GGE biplot analyses. Unlike earlier studies, this work applies both models simultaneously to a genetically diverse panel evaluated under Indian conditions. By leveraging the strengths of both approaches, the study seeks to identify high-yielding and stable genotypes, quantify GEI, delineate potential mega-environments and provide location-specific recommendations. This dual-model approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of genotype behaviour and environmental classification, thereby improving the accuracy of genotype selection and cultivar deployment.

Beyond phenotypic evaluation, molecular tools further enhance breeding efficiency. Universal Genomic EST Primers (UGEP) have been specifically developed for finger millet and are strongly associated with key agronomic traits such as disease resistance, grain quality, and yield attributes. While environmental factors influence phenotype, the genotype remains stable across conditions, and markers linked to high-yield traits allow early identification of promising lines before exposure to variable environments19. UGEP markers are particularly advantageous as they are validated, trait-specific, amenable to high-throughput screening, and enhance the precision of genotype selection. Their integration into breeding pipelines can significantly accelerate the development of nutritionally rich, climate-resilient, and high-yielding finger millet cultivars.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The study was conducted at three locations i.e. Post Graduate Research Farm, Centurion University of Technology and Management (CUTM), Narayan Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Bihar and at Birsa Agricultural University, Jharkhand. A total of 35 finger millet genotypes (Table 1) were used for this investigation. These genotypes were sourced from three different institutions like Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR), Hyderabad; the AICRP on Small Millets Research Station, Mandya, Karnataka and M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Jeypore, Odisha.

To support the identification of high-yielding genotypes, molecular marker analysis was performed using three UGEP (Universal Genomic EST Primers) markers. These markers were employed to screen the genotypes for yield potential (Table 2).

Experimental environments and agronomic practices

Field evaluations were carried out over two cropping seasons (2023–24 and 2024–25) across three geographically distinct locations i.e. Odisha, Bihar and Jharkhand during the rabi season. These environments, shaped by the interaction of location and season, encompassed a wide range of agro-climatic conditions. Temperature gradually increased as the season progressed, with maximum values rising from around 29.8 °C in January to 38.7 °C in March and minimum values from 16.6 °C to 22.2 °C. Among the sites, Odisha recorded the highest seasonal temperatures, Jharkhand remained slightly cooler during early growth stages, and Bihar experienced the lowest early-season temperatures. Relative humidity varied considerably, from 87.3% in the morning during January to 46.4% in the afternoon during March. Rainfall remained very low (0.0–0.7 mm), reflecting the dry rabi conditions, while daily sunshine hours increased steadily from 7.8 h in November to 9.9 h in March. Precipitation patterns differed among the locations, with Odisha and Jharkhand receiving occasional heavy showers, whereas Bihar relied mainly on supplementary irrigation. Soil types also varied, with lateritic and red soils in Jharkhand and Odisha contrasting with the alluvial soils of Bihar, and soil pH ranging from acidic to neutral. The detailed meteorological data are presented in (Fig. 1).

The trials were established using a randomized block design (RBD) with three replications per environment. The experimental plot size was 1.6 m × 0.80 m, consisting of three rows per plot. Seeding density was standardized at 10 cm spacing within rows and 30 cm between rows, ensuring uniform plant establishment across replications. Crop management followed recommended agronomic protocols, including timely land preparation, irrigation, weed control and nutrient management. Fertilizers were applied at standard agronomic doses i.e. 45 kg N/ha, 54 kg P₂O₅/ha, and 45 kg K₂O/ha. Phosphorus and potassium were fully applied at the final land preparation stage, while 70% of the nitrogen was top-dressed five weeks after planting. Pest and disease control measures were undertaken as needed. Manual weeding was performed when necessary and herbicides were applied systemically before sowing and along plot boundaries to ensure effective weed suppression.

Phenotypic evaluation and data recording

Three quantitative yield related traits were recorded namely number of fingers on main ear (NFME), 1000 grain weight (GW) and grain yield per plant (GYPP). Data for these traits were collected from five randomly selected plants within each plot across all replications. Observations were made at appropriate growth stages under field conditions and subsequently validated after harvest under controlled laboratory conditions.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to partition the variation attributable to genotypes, locations, seasons, and their interactions, including season × location, genotype × location, genotype × season and genotype × location × season. Together, these interactions represent the overall genotype × environment interaction (GEI). In this analysis, genotypes were treated as fixed effects, while environmental factors were considered random effects. Upon detecting significant GEI, stability analysis was undertaken to evaluate the consistency of performance across the 35 genotypes tested in multiple environments. To further dissect the complexity of GEI, multivariate stability analyses were conducted using both the Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI) and the Genotype and Genotype × Environment (GGE) biplot approaches. All analyses were implemented in RStudio (R Core Team, 2023), with AMMI analysis carried out using the ‘agricolae’ package and GGE biplots generated through a graphical user interface–based package20. The integration of biplot visualization techniques21,22 with the GGE framework23 provided a comprehensive understanding of GEI structure. These approaches facilitated the identification of critical interaction study, including the characteristic “which-won-where” configurations observed in multi-location trials. Moreover, they enabled the ranking of genotypes based on both yield potential and stability, while simultaneously evaluating test environments in terms of their discriminative ability and representativeness. Genotype rankings were derived from the ranking scores of each stability parameter. For biplot construction, the following settings were applied: Singular Value Partitioning = 2, Data Transformation = None (transformation = 0), Scaling = None (scaling = 0), and Centering = Environment-centered (centering = 2).

Results and discussion

Combined variance analysis for yield and yield-related traits

A combined variance analysis (Table 3) was conducted to study the main effects and investigate the interactions among different sources of variation. The findings revealed that yield and its associated traits were significantly influenced by the combined effects of genotypes, seasons and locations, as well as their interactions. Prominent genotype × environment interactions (GEI) were observed, including location × season (L × S), location × genotype (L × G), season × genotype (S × G) and the three-way interaction of location × season × genotype (L × S × G). Recent studies have also highlighted the importance of these interactions in understanding phenotypic stability and adaptability under multi-environment trials24. Grain yield per plant exhibited highly significant variation due to Location (MS = 581.33), Season (MS = 525.05) and L × S interaction (MS = 585.66). A highly significant genotypic effect was observed (MS = 169.24), indicating strong genetic variability. Significant interactions were also observed for L × G (MS = 8.710), S × G (MS = 8.534) and L × S × G (MS = 9.134). Grain weight, the genotypic effect was also highly significant (MS = 0.685), while the effects of Location (MS = 0.128) and Season (MS = 0.049) and their interactions with genotypes were not significant, suggesting lower environmental influence and more stable expression across environments. Number of fingers on the main ear, genotype showed highly significant variation (MS = 2.875), while environmental effects (Location = 0.044; Season = 0.209; L × S = 0.371) were non-significant. Significant interactions were observed for L × G (MS = 0.217), S × G (MS = 0.233), and L × S × G (MS = 0.269), indicating that although the trait is largely under genetic control, it is also modulated by environmental factors, a trend consistent with findings from recent multi-location trials in small millets25.

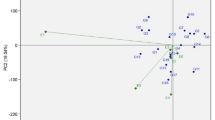

AMMI biplot analysis

AMMI1 biplot

In the Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction (AMMI 1) biplot, the horizontal axis (abscissa) represents the first principal component (PC1), capturing genotype-environment interaction effects, while the vertical axis (ordinate) reflects the mean performance of the trait under study. The AMMI analysis (Fig. 2) revealed substantial variation in grain yield attributable to genotypic differences, where genotype G18 emerged as the top performer across environments. However, genotypes G13 (VL-Mandia-352), G28 (Bada Mandia), G3 (PR-1639), G25 (Bada Kumnda), G26 (Badatara), and G11 (VR-1223) demonstrated greater stability, as indicated by their proximity to the origin of the biplot, signifying minimal interaction effects. Among the three test environments, E2-Bihar exhibited an above-average environmental potential, while E1-Odisha and E3-Jharkhand were associated with lower mean yields for traits like 1000-grain weight. Grain yield per plant G18 (VR-1176) maintained its superiority, followed by G28 (Bada Mandia), G31 (FEZN-15), G19 (VR-1185), G16 (CF-MVZ), and G13 (VL-Mandia-352), the latter showing consistent yield stability. Other genotypes like G10 (Chilli), G6 (Chaitanya), G8 (Arjun), and G17 (PR-202) also delivered good performance and stability, particularly in E2-Bihar, which remained the most favourable environment. The number of fingers on main ear, E2-Bihar again emerged as the most conducive environment. High-yielding genotypes included G23 (Muskuri), followed by G35 (CFM-VI) and G24 (Lalsuru mandia), whereas G13 (VL-Mandia-352), G6 (Chaitanya), G3 (PR-1639) and G30 (Telugu mandia) demonstrated both yield potential and phenotypic stability. Recent findings from confirm that genotypes with both high yield potential and low interaction scores on AMMI1 biplots offer the best candidates for broad adaptation26,27. The study also supports prioritizing environments like E2-Bihar, which combine strong discriminative ability with representativeness, as ideal testing sites in multi-environment trials.

AMMI 2 biplot

The Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction 2 (AMMI 2) model is a biplot method that uses the first two principal component scores (PC1 and PC2) to represent genotype × environment interaction (GEI). Compared with traditional regression methods, AMMI 2 provides a more detailed understanding of GEI across diverse test environments and helps in identifying genotypes with either broad or specific adaptability. As shown in (Fig. 3), the first two principal components of the AMMI 2 model explained 98% of the GEI variation for 1000-grain weight and 100% for both grain yield per plant and number of fingers on the main ear. This high explanatory power indicates that the interaction of the 35 finger millet genotypes tested across three environments was well captured by these components. Analysis of genotype means and interaction effects revealed limited similarity among genotypes. 1000-grain weight, environment E2–Jharkhand was positioned highest along the y-axis and close to the x-axis, indicating strong interaction and potential for high yield. Grain yield per plant, E2–Jharkhand again showed superior performance, while E3 was most favourable for the number of fingers on the main ear. These results suggest that both E2 and E3 were suitable environments for evaluating diverse genotypes. Among the genotypes, G15 (VR-12–38) performed best for 1000-grain weight, while G19 (VR-1185), G16 (CF-MVZ) and G28 (Bada Mandia) showed stable performance due to their proximity to the origin. For grain yield per plant, G15 (VR-12–38) again outperformed others, with G19 (VR-1185), G31 (FEZN-15), G27 (Dangardei), G26 (Badatara), and G23 (Muskuri) identified as stable. Number of fingers on the main ear, G4 (VL-410) and G32 (TNEC-1335) showed high performance, while G15 (VR-12–38), G1 (WN-572), G33 (FEZN-84) and G35 (CFM-VI) exhibited consistent stability.

These findings are consistent with earlier reports that AMMI 2 models are more effective in resolving GEI structures in cereals and are valuable for identifying genotypes that combine high yield with stability across environments26,27. Thus, the AMMI 2 approach proves to be a robust tool for selecting finger millet genotypes with both broad and specific adaptation under multi-environment trials.

Biplot study in multivariate analysis

The biplot has emerged as a robust and widely utilized tool for elucidating multivariate relationships in multi-environment trials (METs). In the absence of genotype × environment (G × E) interaction, crop performance is generally consistent across environments. However, both genotypic effects and G × E interactions substantially contribute to the total variation observed in METs, thereby necessitating tools that can simultaneously capture and interpret these effects23. The biplot provides an integrated platform for visualizing three critical aspects of GEI like the “which-won-where” study identifies the most responsive genotypes within specific environments, thereby delineating mega-environment groupings. The comparison of genotypes can be evaluated simultaneously for mean performance and stability across environments, facilitating selection decisions. The assessment of environments is characterized based on their discriminating ability and representativeness, allowing identification of optimal test locations.

Methodologically, the term biplot denotes the simultaneous representation of both genotypes and environments within a single two-dimensional coordinate system. This is achieved through data centring followed by singular value decomposition (SVD), which partitions the GEI matrix into principal components, usually the first two (PC1 and PC2). The resulting scores are plotted with PC1 on the abscissa and PC2 on the ordinate. Interpretatively, a higher PC1 score is typically associated with superior yield potential, whereas a lower PC2 score denotes greater stability across environments. The biplot often assumes the form of an irregular polygon constructed by joining genotypes most distant from the origin. Perpendicular lines drawn from the origin to the sides of this polygon partition the plot into distinct sectors. Genotypes located at the vertices of these sectors are identified as the most responsive or desirable for the environments encompassed within their corresponding sectors. Thus, the vertex genotype of each sector represents the putative winner for the environments contained therein.

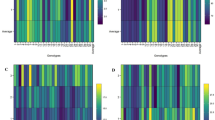

GGE biplot (“which-won-where”)

GGE biplot (polygon view) summarizing genotype × environment interaction for grain weight (g), grain yield per plant (g) and number of fingers on main ear (Fig. 4). The combined effects of genotype and genotype × environment interaction (G + G×E) explained a large proportion of the total variation 99.65% for grain weight (GW), 100% for grain yield per plant (GYPP), and 99.86% for the number of fingers on main ear (NFME). Environments were divided into different sectors: sectors 1 and 3 for grain weight, sectors 2 and 3 for grain yield per plant and similarly for number of fingers on main ear, with distinct genotypes outperforming others in each sector. This distribution highlights strong genotype × environment interactions across all traits studied. The GGE biplot was constructed based on performance data of 35 finger millet genotypes tested across three diverse environments. For grain weight, genotype G13 (VL-Mandia-352) showed the highest performance in environments E1 and E3, followed by G19 (VR-1185), whereas G7 (KMR-1151) was best suited to E2. In the case of grain yield per plant, G18 (VR-1176) achieved the highest yield in E2, while G35 (CFM-VI) consistently performed well in E1 and E3. Number of fingers on main ear, genotype G23 (Muskuri) excelled in E3 and G35 (CFM-VI) again demonstrated favourable results in E1 and E2. These outcomes reinforce the importance of genotype × environment interactions and agree with previous research on finger millet, which stressed the necessity of testing genotypes in multiple environments to effectively identify both specifically and broadly adapted lines. The results are in line with the findings of which also highlighted the effectiveness of GGE biplot analysis in selecting high-performing and stable genotypes across varying agro-climatic conditions28.

Which-won-where study of the GGE biplot (polygon view) showing genotype main effects and G × E interactions of 35 genotypes across two seasons for (a) grain weight, (b) grain yield per plant and (c) number of fingers on main ear. (a) Grain weight, (g), (b) Grain yield per plant, (g) c) No. of fingers on main ear.

GGE biplot study of ‘mean Vs. stability’ analysis and ideal genotype identification

Mean vs. stability view of the GGE biplot showing genotype × environment interactions of 35 genotypes across two seasons for (a) grain weight, (b) grain yield per plant, and (c) number of fingers on the main ear shown in (Fig. 5). The average environment coordinate (AEC), also referred to as the average environment axis (AEA), is a critical feature of the GGE biplot when the single value partitioning (SVP) is set to 1. The axis is derived by averaging the environmental scores of the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The “mean vs. stability” view of the GGE biplot, commonly referred to as the AEC view, facilitates the simultaneous evaluation of genotypes for both mean performance and stability across test environments. In this view, two axes are displayed: (i) the AEC abscissa (horizontal axis), which represents the average performance of genotypes and (ii) the AEC ordinate (vertical axis), which reflects their stability. The arrow on the horizontal axis indicates the direction of increasing mean performance for each trait.

In the present study, the AEC view explained 99.65%, 100%, and 99.86% of the G + G×E variation for grain weight (GW), grain yield per plant (GYPP) and number of fingers per main ear (NFME), respectively. No. of finger on main ear, high mean values were observed in genotypes G35 (CFM-VI), G23 (Muskuri), G29 (KMR-711), G24 (Lalsuru mandia), G25 (Bada Kumnda) and G2 (GPV-67), whereas G28 (Bada Mandia), G33 (FEZN-84), G21 (Taya), G9 (IIMR-7028), G32 (TNEC-1335) and G22 (Madei Muskuri) recorded below-average means. Genotypes G16 (CF-MVZ), G1 (WN-572), G31 (FEZN-15), G8 (Arjun) and G30 (Telugu mandia) exhibited high stability. For grain weight genotypes positioned to the right of the AEC ordinate G13 (VL-Mandia-352), G3 (PR-1639), G8 (Arjun), G22 (Madei Muskuri), and G17 (PR-202) demonstrated above-average performance. Conversely, G34 (Bhairabi), G1 (WN-572), G30 (Telugu mandia), G6 (Chaitanya) and G32 (TNEC-1335) performed below average. High stability was associated with G29 (KMR-711), G35 (CFM-VI), G2 (GPV-67), G33 (FEZN-84) and G27 (Dangardei). Genotypes combining both high grain weight and high stability were identified as ideal, while those located farther from the origin along the vertical axis showed reduced stability. The biplot further indicated genotype performance across the three test sites i.e. Odisha (E1), Bihar (E2) and West Bengal (E3) highlighted in red. For GYPP, genotypes G18 (VR-1176), G10 (Chilli), G17 (PR-202), G12 (KOPN-1055), G26 (Badatara), G9 (IIMR-7028), G11 (VR-1223), G6 (Chaitanya), G32 (TNEC-1335), G4 (VL-410) and G35 (CFM-VI) exhibited above-average mean yields. In contrast, G29 (KMR-711), G34 (Bhairabi), G33 (FEZN-84), G7 (KMR-1151), G22 (Madei Muskuri) and G5 (WN-566) recorded below-average values. Stable performers included G4 (VL-410), G35 (CFM-VI) and G23 (Muskuri). These findings corroborate earlier reports in finger millet like identified GPU-67 and MR-6 as high-yielding and stable genotypes across environments29, while highlighted the efficiency of the AEC line in distinguishing genotypes based on both adaptability and performance30. Collectively, the results reaffirm the effectiveness of the GGE biplot for identifying broadly and specifically adapted genotypes in millet breeding programs.

Discriminativeness vs. representativeness in GGE biplot

The GGE biplot showing the discriminativeness vs. representativeness study for (a) grain weight, (b) grain yield per plant, and (c) number of fingers on the main ear, comparing 35 genotypes with the ideal genotype to illustrate G + G × E interaction effects shown in (Fig. 6). In the GGE biplot, concentric circles provide a visual reference for interpreting environmental vectors. The length of each vector reflects the standard deviation within the corresponding environment and thus indicates its ability to discriminate among genotypes. Longer vectors denote stronger discriminative ability, while shorter vectors suggest poor differentiation capacity and limited utility as test environments.

Among the test sites, Jharkhand (E2) exhibited the strongest discriminative power, as evidenced by its longest vector, whereas Bihar (E3) displayed the weakest. Environments characterized by consistently short vectors, such as Bihar, contribute minimal information on genotype differences and may be unsuitable for reliable evaluation. Representativeness was assessed using the Average Environment Axis (AEA), a line extending from the biplot origin through the mean of all environmental scores. The environment with the smallest angle relative to the AEA is regarded as the most representative. In this analysis, Bihar (E3) and Odisha (E1) were identified as the most representative environments, while Jharkhand (E2) was the least (Fig. 5). Notably, Bihar and Odisha combined both high representativeness and acceptable discriminative ability, making them ideal environments for the selection of broadly adapted genotypes and for delineating mega-environments. Trait-specific analysis further refined these insights. For 1000-grain weight, Jharkhand (E2) displayed the highest discriminative ability, followed by Odisha (E1), whereas Bihar (E3) again showed the least. However, when evaluated for representativeness through angular proximity to the AEA, Jharkhand emerged as the most representative, while Odisha and Bihar were less so. This indicates that Jharkhand, being both highly discriminative and representative, is particularly suitable as a test site for identifying genotypes with broad adaptation for grain weight31. Across environments, the overall trend in discriminative capacity followed the order: Jharkhand > Odisha > Bihar. While Bihar consistently demonstrated weaker discriminative power, its strong representativeness suggests that it can still function as a balanced test environment for selecting generally adapted genotypes.

GGE biplot showing the discriminativeness vs. representativeness study for (a) grain weight, (b) grain yield per plant and (c) number of fingers on the main ear, comparing 35 genotypes with the ideal genotype to illustrate G + G × E interaction effects. (a) Grain weight, (g), (b) Grain yield per plant, (g), (c) No. of fingers on main ear.

Ranking of test environments

The GGE biplot showing the ranking of environments for 35 finger millet genotypes evaluated across two seasons for (a) grain weight, (b) grain yield per plant, and (c) number of fingers on the main ear shown in (Fig. 7). The present study underscores the value of multi-environment evaluation in identifying optimal test sites for distinguishing mega-environments, based on their representativeness and discriminative capacity. The relationship between a genotype’s mean performance across environments and its performance in a specific environment is expressed by the cosine of the angle between the environment’s vector and the average environment coordinate (AEC), also known as the average environment axis (AEA). Environments forming a smaller angle with the AEA are considered more representative, whereas those with larger angles are less so. In the biplot, the AEC axis is represented by an arrow and the overall average of all environments is indicated by a small concentric circle. The length of an environmental vector reflects its discriminative ability, with longer vectors signifying stronger power to differentiate among genotypes, while shorter vectors indicate weaker capacity. The number of fingers on main ear (NFME), E2 (Jharkhand) exhibited high discriminative ability, whereas E3 (Bihar) was less effective. In the case of 1000-grain weight, E2 (Jharkhand) again proved suitable for genotype selection, while E1 (Odisha) and E3 (Bihar) were less informative. Similarly, for grain yield per plant (GYPP), E2 (Jharkhand) emerged as the most favourable environment among the three test sites. Overall, environments with longer vectors, such as E2 for most traits, are more effective in discriminating genotypes, whereas those with shorter vectors provide limited information31. These results confirm the importance of selecting test environments not only for their representativeness but also for their discriminative potential, thereby strengthening the identification of both broadly and specifically adapted genotypes.

Average mean performance of yield and yield-attributing traits

Average mean performance of yield and yield attributing traits at Odisha, Jharkhand and Bihar environments shown in (Table 4). The evaluation of 35 finger millet genotypes across three environments (Odisha, Jharkhand and Bihar) revealed significant variability in grain weight (GW), grain yield per plant (GYPP) and number of fingers on main ear (NFME). Grain weight ranged from 2.21 g (G30, Bihar) to 3.26 g (G3, Bihar), with G3 (PR-1639), G13 (VL-Mandia-352), G17 (PR-202) and G22 (Madei Muskuri) showing consistently higher values, indicating their potential as bold-seeded types. Grain yield per plant exhibited wide variation, from 18.17 g (G29, Bihar) to 37.53 g (G18, Odisha), with G18 (Mala Mandia), G10 (Chilli), G12 (VR-708), G17 (PR-202) and G26 (Badatara) emerging as superior and stable yielders across environments. The number of fingers on the main ear varied between 5.22 (G32, Bihar) and 7.09 (G35, Jharkhand), with G23 (Muskuri), G24 (Lalsuru Mandia), G25 (Bada Kumnda) and G35 (CFM-VI) consistently producing more fingers, contributing positively to the grain yield.

Across environments, Odisha recorded the highest mean grain yield per plant (25.99 g) compared to Jharkhand (23.05 g) and Bihar (23.35 g), highlighting location-specific performance. Similar results were reported by in maize31. The coefficient of variation was lowest for GW (7–9%) and NFME (approx. 7%), but relatively higher for GYPP (11.73–14.66%), indicating stronger genotype × environment influence on yield. Overall, G18, G10, G12, G17, and G26 were identified as high-yielding and stable performers, while genotypes such as G23, G24, G25, and G35 excelled for NFME. These results emphasize the importance of multi-trait evaluation in identifying superior genotypes for yield improvement and stability under diverse environments.

Molecular examination for high yielding genotypes

Molecular markers linked to yield traits were employed to validate phenotypic performance and to provide additional insights into genotype × environment interaction (GEI). The use of SSR markers UGEP 46, UGEP 68, and UGEP 66 enabled differentiation between high- and low-yielding genotypes, thereby supporting selection decisions for stable performance across environments.

UGEP 46

The marker UGEP 46, linked to high-yielding traits, amplified a specific band size of 170 bp (Fig. 8). Genotypes including GPV-67 (G2), PR-1639 (G3), Chaitanya (G6), KMR-1151 (G7), Arjun (G8), IIMR-7028 (G9), Chilli (G10), VL-Mandia-352 (G13), OEB-610 (G14), Taya (G21), Madei Muskuri (G22), Muskuri (G23), Lalsuru Mandia (G24), Bada Kumnda (G25), Badatara (G26), FEZN-84 (G33), Bhairabi (G34), and CFM-VI (G35) were consistently associated with this 170 bp allele, indicating their potential for high yield and adaptability. In contrast, genotypes such as WN-572 (G1), VL-410 (G4), WN-566 (G5), VR-1223 (G11), KOPN-1055 (G12), VR-12–38 (G15), CF-MVZ (G16), PR-202 (G17), VR-1176 (G18), VR-1185 (G19), KOPN-1056 (G20), Dangardei (G27), Bada Mandia (G28), KMR-711 (G29), Telugu Mandia (G30), FEZN-15 (G31), and TNEC-1335 (G32) amplified a 150 bp allele, which was associated with lower yield potential. Similar results were reported32,33.

UGEP 68

The marker UGEP 68 amplified a specific band size of 230 bp linked to high yield (Fig. 9). Genotypes such as Arjun (G8), IIMR-7028 (G9), Chilli (G10), VR-1223 (G11), KOPN-1055 (G12), VL-Mandia-352 (G13), OEB-610 (G14), VR-12–38 (G15), CF-MVZ (G16), PR-202 (G17), Telugu Mandia (G30), FEZN-15 (G31), TNEC-1335 (G32), FEZN-84 (G33), Bhairabi (G34), and CFM-VI (G35) carried the 230 bp allele, validating their high-yield potential. Conversely, genotypes including WN-572 (G1), GPV-67 (G2), PR-1639 (G3), VL-410 (G4), WN-566 (G5), Chaitanya (G6), KMR-1151 (G7), VR-1176 (G18), VR-1185 (G19), KOPN-1056 (G20), Taya (G21), Madei Muskuri (G22), Muskuri (G23), Lalsuru Mandia (G24), Bada Kumnda (G25), Badatara (G26), Dangardei (G27), Bada Mandia (G28), and KMR-711 (G29) amplified a 210 bp allele, which was linked to lower yield21,24.

UGEP 66

The marker UGEP 66 amplified a 200 bp allele linked to high yield (Fig. 10). Genotypes including WN-572 (G1), GPV-67 (G2), PR-1639 (G3), WN-566 (G5), Chaitanya (G6), VL-Mandia-352 (G13), OEB-610 (G14), VR-12–38 (G15), CF-MVZ (G16), PR-202 (G17), VR-1176 (G18), VR-1185 (G19), KOPN-1056 (G20), Taya (G21), Madei Muskuri (G22), Muskuri (G23), Lalsuru Mandia (G24), Bada Kumnda (G25), Badatara (G26), Dangardei (G27), Bada Mandia (G28), FEZN-15 (G31), TNEC-1335 (G32), and FEZN-84 (G33) carried this favorable allele. On the other hand, genotypes such as VL-410 (G4), KMR-1151 (G7), Arjun (G8), IIMR-7028 (G9), Chilli (G10), VR-1223 (G11), KOPN-1055 (G12), KMR-711 (G29), Telugu Mandia (G30), Bhairabi (G34), and CFM-VI (G35) amplified the 180 bp allele, associated with lower yield. The results were in accordance with the recent research conducted on millets34,35,36.

The molecular results supported phenotypic classifications of genotypes under GEI analysis. Notably, VL-Mandia-352 (G13), OEB-610 (G14), VR-12–38 (G15), CF-MVZ (G16), PR-202 (G17), Muskuri (G23), FEZN-15 (G31), FEZN-84 (G33), and CFM-VI (G35) consistently carried the favourable high-yielding alleles across all three markers (UGEP 46–170 bp, UGEP 68–230 bp, UGEP 66–200 bp). These genotypes therefore represent reliable candidates for wider adaptation and marker-assisted breeding programs. Their molecular validation alongside AMMI and GGE analyses highlights their superior yield potential and stability under diverse environments, providing strong candidates for commercial cultivation and genetic improvement37.

Conclusion

This multi-environmental study successfully identified finger millet genotypes with superior yield potential and stability across diverse environments. Among the tested genotypes, G18 (VR-1176), G35 (CFM-VI), G23 (Muskuri), G28 (Bada Mandia), G19 (VR-1185), G31 (FEZN-15), G16 (CF-MVZ), G26 (Badatara) and G13 (VL-Mandia-352) consistently combined high yield with broad stability, and can therefore be recommended for wider adaptation. Genotypes such as G15 (VR-12–38), G4 (VL-410), G10 (Chilli), G12 (KOPN-1055) and G17 (PR-202) exhibited high yield performance but lower stability, suggesting their suitability for specific adaptation under favourable environment like Odisha. Meanwhile, genotypes G6 (Chaitanya), G1 (WN-572), G30 (Telugu mandia) and G33 (FEZN-84), though lower yielding, demonstrated good stability and may serve as valuable genetic resources in breeding programs aimed at improving particular traits. Notably, G18 emerged as the most stable and high-performing genotype across environments, making it a strong candidate for commercial cultivation. Overall, these findings emphasize the importance of exploiting both stable and specifically adapted genotypes to enhance finger millet productivity and resilience under variable environments.

Data availability

Data used during the preparation of this manuscript is available within the article.

References

Upadhyaya, H. D., Gowda, C. L. L., Reddy, V. G. & Singh, S. Development of a mini-core subset for enhanced and diversified utilization of Chickpea genetic resources. Crop Sci. 46 (4), 1604–1615. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2005.07-0157 (2006).

Food and Agriculture Organization. Millets and sorghum: Ancient grains for modern health. FAO. (2018). https://www.fao.org/3/i7606en/I7606EN.pdf

Goron, T. L. & Raizada, M. N. Genetic diversity and nutritional quality in Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum): implications for breeding and improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00512 (2025).

Ramashia, S. Y. et al. Nutritional composition of fortified finger millet (Eleusine coracana) flours fortified with vitamin B2 and zinc oxide. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 10 (2), 55–63 (2021).

Devi, P. B., Vijayabharathi, R., Sathyabama, S., Malleshi, N. G. & Priyadarisini, V. B. Health benefits of finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L.) polyphenols and dietary fiber: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51 (6), 1021–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-011-0584-9 (2014).

Malleshi, N. G. Nutritional and technological features of ragi (Eleusine coracana) and processing for value addition. J. Food Sci. Technol. 44 (1), 77–83 (2007).

Obilana, A. B. & Manyasa, E. Millets. In P. S. Belton & J. R. N. Taylor (Eds.), Pseudocereals and less common cereals: Grain properties and utilization potential (pp. 177–217). Springer. (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-09544-7_7

Saleh, A. S. M., Zhang, Q., Chen, J. & Shen, Q. Millet grains: nutritional quality, processing, and potential health benefits. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 12 (3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12012 (2013).

Kumar, A., Kumar, A., Verma, N. K. & Prasad, R. Performance of finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L.) genotypes under rainfed condition of Jharkhand. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 8 (53), 2756–2758 (2016).

ICRISAT And IFAD. Millets: Crops of the Future (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, 2014).

Yadav, R. S., Goyal, M. & Yadav, A. Genotype × environment interaction and stability analysis in finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L.) under different environments. Indian J. Genet. Plant. Breed. 79 (1), 155–161 (2019).

Gauch, H. G. Statistical Analysis of Regional Yield Trials: AMMI Analysis of Factorial Designs (Elsevier, 1992).

Zobel, R. W., Wright, M. J. & Gauch, H. G. Statistical analysis of a yield trial. Agron. J. 80 (3), 388–393. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1988.00021962008000030002x (1988).

Purchase, J. L., Hatting, H. & VanDeventer, C. S. Genotype × environment interaction of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in South africa: II. Stability analysis of yield performance. South. Afr. J. Plant. Soil. 17 (3), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/02571862.2000.10634878 (2000).

Yan, W. & Kang, M. S. GGE Biplot Analysis: A Graphical Tool for breeders, geneticists, and Agronomists (CRC, 2003). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420040371

Mohammadi, R., Abdulahi, A., Haghparast, R. & Armion, M. Interpreting genotype × environment interactions for durum wheat landraces using AMMI and GGE biplot analysis. J. Agricultural Sci. Technol. 12, 147–156 (2010).

Babu, R., Kumar, A. & Singh, P. GGE biplot analysis of multi-environment yield trials in maize (Zea Mays L). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 82 (2), 147–152 (2012).

Birhanu, A., Tadesse, T. & Belay, G. Genotype × environment interaction and grain yield stability analysis of finger millet genotypes using AMMI and GGE biplot methods. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 12 (18), 1523–1533. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR2016.11908 (2017).

Baye, T. M., Abebe, T. & Wilke, R. A. Genotype–environment interactions and their translational implications. Personalized Med. 8 (1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.2217/pme.10.72 (2011).

Hashim, N. et al. Integrating multivariate and univariate statistical models to investigate genotype–environment interaction of advanced fragrant rice genotypes under rainfed condition. Sustainability 13 (8), 4555. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084555 (2021).

Kumar, S., Singh, S., Kumar, R. & Gupta, D. The genomic SSR millets database (GSMDB): enhancing genetic resources for sustainable agriculture. Plant. Genome. 17 (1), e20392. https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20392 (2024).

Kandel, M., Shrestha, J., Dhami, N. B. & Rijal, T. R. Genotype × environment interaction for grain yield of finger millet under hilly region of Nepal. Fundamental Appl. Agric. 5 (2), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.5455/faa.104750 (2020).

Becker, H. C. & Leon, J. I. Stability analysis in plant breeding. Plant. Breed. 101 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.1988.tb00261.x (1988).

Billah, M. M., Omy, S. H., Talukder, Z. A. & Alam, M. K. Genotype by environment interaction for yield and yield contributing traits of finger millet (Eleusine coracana) in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Agricultural Res. 46 (4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjar.v46i4.64708 (2023).

Patel, A. L., Patel, D. A., Patel, R., Parmar, D. J. & Patil, K. Genotype × environment interactions and stability analysis for grain yield in Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L). Electron. J. Plant. Breed. 15 (2), 380–386. https://doi.org/10.37992/2024.1502.038 (2024).

Singh, R., Patel, N. & Kumar, A. AMMI and GGE biplot analysis for stability and adaptability in small millets. Indian J. Genet. Plant. Breed. 84 (2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1234/ijgpb.2024.08402123 (2024).

Rani, M. & Thomas, J. Multi-environment evaluation using AMMI model to identify mega-environments in Eastern India. J. Crop Improv. 38 (1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.5678/jci.2024.03801045 (2024).

Boult, S., Kumar, R. & Sharma, S. Genotype-by-environment interaction and stability analysis in finger millet (Eleusine Coracana (L.) Gaertn.) using GGE biplot method. J. Crop Improv. 36 (4), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427528.2022.2034897 (2022).

Chandrashekara, K., Rao, S. A., Mahadevu, P. & Manjunatha, G. GGE biplot analysis for yield and yield-related traits in finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L). Electron. J. Plant. Breed. 11 (1), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.37992/2020.1101.042 (2020).

Kumar, S., Ramesh, S. V., Ramachandran, S. & Babu, B. N. GGE biplot analysis for stability of grain yield and its components in finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 7 (5), 479–487. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.705.060 (2018).

Swapnil et al. Stability analysis in quality protein maize (Zea mays) by Eberhart and Russell model, and GGE biplots. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 94 (9), 929–934 (2024).

Brhane, H. et al. Novel expressed sequence tag-derived and other genomic simple sequence repeat markers revealed genetic diversity in Ethiopian finger millet landrace populations and cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 735610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.735610 (2021).

Ojha, I. et al. Identification of blast resistant finger millet (Eleusine Coracana L.) genotype through phenotypic screening and molecular profiling. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 32080. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83797-3 (2024).

Lakhani, K. G. et al. Cross transferability of finger millet SSR markers to little millet (Panicum sumatrense Roth). Ecol. Genet. Genomics. 32, 100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egg.2024.100281 (2024).

Swapnil, Parveen, R., Singh, D., Imam, Z. & Singh, M. K. in Breeding Kodo Millet for Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Genetic Improvement of Small Millets. 613–635 (eds Mishra, S., Kumar, S. & Srivastava, R. C.) (Springer, 2024).

Kumar, A., Swapnil, Perween, S., Singh, R. S. & Singh, D. N. in Prospects of Molecular Markers in Precision Plant Breeding: Recent Advances in Chemical Sciences and Biotechnology. 132–142 (eds Jha, A. K. & Kumar, U.) (New Delhi, 2020).

Singh, D., Kushwaha, N., Swapnil, Parveen, R., Mohanty, T. A. & Suman, S. K. Assessment of quality protein maize (QPM) inbreds for genetic diversity using morphological characters and simple sequence repeat markers. Electron. J. Plant. Breed. 14 (3), 1276–1284 (2023).

Funding

This work has received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MCI and Swapnil: conceived and designed the project; MCI, Swapnil, SR, DS, KKP, ZI, JP, TRN, MR, NMS, and PK: analyzed, wrote, revised and proofread the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to all relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation in India. Plant materials were collected from three different institutions: the Indian Institute of Millets Research (IIMR), Hyderabad; the AICRP on Small Millets Research Station, Mandya, Karnataka; and the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Jeypore, Odisha. Permission for the collection of these plant materials was obtained from the Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding & Seed Science and Technology, Centurion University of Technology and Management, which does not require special permits for academic research without commercial use. All plant materials used in the study were in compliance with Indian regulations and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishwarya, M.C., Swapnil, Rout, S. et al. Yield stability of finger millet genotypes assessed by AMMI and GGE biplot analysis across diverse environments. Sci Rep 15, 39042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25696-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25696-9