Abstract

The impact of statins on patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate whether statins influence overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in aHCC patients receiving Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab (A + B). ARTE is a prospectively maintained dataset of 305 aHCC patients treated with A + B. Among these, 63 patients receiving statins were identified and propensity score-matched to 63 non-statin users. Primary outcomes were OS and PFS, while treatment discontinuation due to liver-related events was assessed as a secondary outcome. The median treatment duration was 6.4 months (IQR 2.7–13.2). Among the 126 matched patients, viral etiology was the most common (44.4%), followed by metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (40.5%). Median OS was 23 months [95% CI 17.2–28.7] in statin users vs. 16 months [95% CI 12.8–19.2] in non-users, while median PFS was 12 months [95% CI 4.1–19.9] in statin users vs. 8 months [95% CI 4.0–12.0] in non-users, with no significant differences between groups. In multivariate Cox regression, MASLD-induced HCC was associated with a higher risk of progression or death (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.03–2.75). Statins did not reduce the risk of treatment discontinuation due to liver-related events (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.27–4.14). Statins did not improve OS or PFS, nor did they reduce the risk of treatment discontinuation due to liver-related events in aHCC patients receiving A + B. Notably, MASLD-related HCC exhibited worse PFS, suggesting a potential differential response to systemic therapies, which warrants further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a significant global health challenge, as it is the most prevalent form of primary liver cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality1. Despite diagnostic and therapeutic advancements, the prognosis of patients with HCC remains poor, emphasizing the need for innovative and effective treatment strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Statins, which are inhibitors of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, represent a cornerstone in the treatment of hypercholesterolemia by reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease2. Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that statins may exert anti-tumorigenic effects through different mechanisms, including inhibition of cellular proliferation, promotion of apoptosis, and modulation of the tumor microenvironment3. Moreover, epidemiological studies have revealed an inverse correlation between statin administration and the incidence of HCC, suggesting a possible role in HCC prevention3. Notably, statins might also confer hepatoprotective benefits in cirrhotic patients by mitigating portal hypertension, a hallmark of advanced cirrhosis, and thus reducing the risk of hepatic decompensation events4. Specifically, statin therapy has been shown to counteract the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation and to exert vasodilatory effects on the hepatic microcirculation4.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as agents targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), have demonstrated remarkable efficacy across diverse malignancies by unleashing the anti-tumor immune response5, especially in tumors that exhibit primary drug resistance, such as HCC. Anti-VEGF agents help overcome VEGF-induced immune suppression and thus significantly enhance the therapeutic effects of ICIs6. Regarding HCC treatment, the combination of Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab (A + B) has emerged as a new standard of care for the first-line treatment of advanced HCC, following the results of the IMbrave150 trial, which demonstrated a significant survival benefit compared to sorafenib7. Since the publication of this pivotal trial, several studies have further confirmed the efficacy and safety of A + B in different real-world populations8,9. Interestingly, based on preclinical studies, statins might synergize with ICIs and enhance the anti-tumor immune response by promoting T-cell activation and infiltration within the tumor microenvironment10,11. Furthermore, statins might potentiate the anti-angiogenic effects of bevacizumab by inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation12. However, the precise impact of statin therapy on the progression and clinical course of advanced HCC remains unclear. Therefore, elucidating the intricate interplay between statins, immune modulation, and the tumor microenvironment could help uncover the full therapeutic potential of combinatorial regimens in HCC treatment.

This study primarily aimed to assess the potential effect of statins on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with advanced HCC receiving A + B.

Methods

A total of 305 consecutive patients with unresectable HCC who received A + B in 12 tertiary care Italian centers were enrolled in a prospectively maintained database (the ARTE dataset) from April 30, 2022 to May 31, 2024 and divided into two groups based on statin use (63 statins users vs. 242 non-statins users). All the 63 patients were on statin therapy at the time of HCC diagnosis, and treatment was maintained throughout the study period. The inclusion criteria were: (i) radiological or histological diagnosis of HCC according to international guidelines13; (ii) unresectable HCC defined according to BCLC classification as stage B or C; and (iii) A + B as first-line systemic treatment. Demographic, clinical, and biochemical characteristics—including age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS), BCLC stage, ongoing treatment with statins, etiology of liver disease, baseline Child–Pugh score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels—were recorded at the time of treatment initiation. Prior treatments of underlying etiological factors for chronic liver disease were also recorded.

Regarding etiology of liver disease, Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) was defined, in according to Delphi consensus, as the presence of hepatic steatosis associated with a cardiovascular risk factor and no more than 2 units of alcohol per day in the absence of other causes of liver disease14. Metabolic-alcoholic liver disease (MetALD) was defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis associated with a cardiovascular risk factor and a daily intake of 20 to 50 g of alcohol (or weekly 140–350 g) for females and 30 to 60 g daily for males (or weekly 210–420 g)14.

The decision to administer A + B was made following a multidisciplinary evaluation of the patient and was based on the local practices of each participating institution. All patients received Atezolizumab (1200 mg) plus Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) intravenously every 3 weeks, according to the standard dosing schedule recommended by the manufacturer. Toxicity management, including dose interruption or treatment discontinuation, was conducted in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommendations. Treatment was continued until disease progression or the occurrence of a major adverse event. Radiological assessments were performed at baseline and every 9–12 weeks. HCC progression was defined according to RECIST v1.1 criteria15, based on contrast-enhanced multiphasic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed as part of periodic restaging and assessed by each center.

The primary outcomes were OS, defined as the time from the initiation of treatment until death from any cause, and PFS, defined as the time from the initiation of treatment until disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurs first. The secondary outcome was defined as oncological treatment discontinuation due to a composite of hepatic decompensating events including gastrointestinal bleeding, new-onset or recurrent grade 2–3 ascites, and new-onset or recurrent encephalopathy recurrent in patients who previously exhibited normal levels of consciousness, whichever occurred first.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained following review of the study protocol by the Comitato Etico Area Vasta Emilia Centro (AVEC) (Approval ID: 811/2022/Oss/AOUBo). Written informed consent was obtained from all prospectively enrolled patients.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data, as determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Comparisons between continuous variables were performed using the student’s t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test, with the Fisher’s exact test applied when appropriate.

A 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to minimize confounding, balancing the 63 patients receiving statins and the 242 patients who were not on statin therapy. The propensity score was calculated using logistic regression, including variables that showed a significantly different distribution between groups. After matching, 126 patients were included in the final matched cohort (63 per group). To further account for potential residual confounding and increase statistical power, an Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW) analysis was also conducted. IPTW was computed as 1/propensity score for statin users and 1/(1 − propensity score) for non-users, and the resulting weights were applied in the Cox proportional hazards regression models.

The cumulative probabilities for OS and PFS between the two groups (statin users vs. non-users) were estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared with the log-rank test. To account for potential confounding, univariate and multivariate Cox regression models were used to identify independent predictors of OS and PFS. Covariates with p-value < 0.1 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate models, and the results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The impact of statins on the risk of treatment discontinuation due to liver related events was analyzed using a competing risk framework. Competing risks were defined as events that could preclude or alter the probability of experiencing treatment discontinuation due to hepatic decompensation including gastrointestinal bleeding, new-onset or recurrent ascites, and new-onset or recurrent encephalopathy. The Fine and Gray model was applied, considering liver-related treatment discontinuation, disease progression/death, and other causes as competing risks. The subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR) was calculated and cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) were plotted to visualize event probabilities over time. Results were reported as SHRs with 95% CIs, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

The analysis was performed using R (version 4.2.1)16, MatchIt package17, SS® (SPSS v.25.0, Chicago, Il, USA) and STATA®, (STATA version 15.0, College Station, TX, USA) softwares.

Results

A total of 305 patients (82% male, mean age 68.1 ± 10.3 years) with advanced HCC receiving A + B were included. The general characteristics of the entire population are described in Table 1. The median treatment duration was 6.4 months (IQR 2.7–13.2), whereas the median follow-up time was 10 months (IQR 5.0–15.3). The prevalence of cirrhosis was 75%. The most common HCC etiology was viral (HCV or HBV), found in 180 out of 305 patients (59%), followed by MASLD, diagnosed in 86 patients (28%). MetALD and alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) accounted for 8% and 23% of HCC cases, respectively. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was present in 32% of patients, while hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia were found in 28% and 8% of cases, respectively. Statins were administered to 63 patients (21%). The characteristics of the 126 propensity score-matched patients are reported in Table 2.

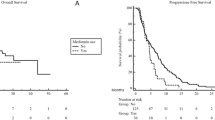

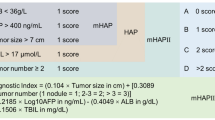

During follow-up, 31 patients (49.2%) non treated with statins and 21 (33%) receiving statins died. No significant difference in OS was observed between the two groups (median, 16 months [95% CI 12.8–19.2] in non-statin users vs. 23 months [95% CI 17.2–28.7] in statin users; log-rank p = 0.09, Fig. 1). The estimated survival rates at 12 and 24 were 61.3% (95% CI 48.2–71.4%) and 21.2% (95% CI 3.5–38.8%) in non-statin users whereas in statin users were 71.3% (95% CI 58.8–83.8%) and 41.1% (95% CI 17.9–64.2%), respectively. In multivariate Cox regression analysis, no variables, including statin use, were significantly associated with OS (Table 3).

A total of 44 patients (69.8%) not receiving statins and 33 (52.4%) treated with statins experienced disease progression or death. PFS did not significantly differ between the two groups (median, 8 months [95% CI 4.0–12.0] in non-statin users vs. 12 months [95% CI 4.1–19.9] in statins users; log-rank p = 0.1, Fig. 2). The estimated PFS rates at 12 and 24 months were 41.2% (95% CI 35.5–63.3%) and 14.9% (95% CI 1.4–28.4%) in non-statin users, and 49.4% (95% CI 35.4–63.3%) and 23.2% (95% CI 9.5–36.9%) in the statin group. In multivariate Cox regression analysis, MASLD-induced HCC was associated with a higher risk of disease progression or death (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.03–2.75, p = 0.04, Table 4).

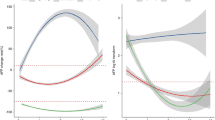

Regarding the secondary outcome, competing risk analysis demonstrated that statin administration did not significantly affect the risk of treatment discontinuation due to liver decompensating events (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.27–4.14) (Fig. 3).

The IPTW analysis confirmed the aforementioned results, with statin use not significantly affecting OS or PFS [HR 0.701, 95% CI 0.423–1.131] after applying weights.

Discussion

In a propensity score-matched cohort of 126 patients with advanced HCC, the coadministration of statins and A + B did not result in a significant improvement in either OS or PFS compared to A + B alone. Moreover, competing risk analysis indicated that statin therapy was not significantly associated with a reduced risk of treatment discontinuation due to incident liver decompensating events during follow-up. These findings appear to contrast with the promising biological effects of statins observed in preclinical models, suggesting that their antitumor potential may not translate into clinical benefit in the context of immunotherapy-treated advanced HCC, at least over the available follow-up period. Interestingly, Cox regression analyses identified MASLD-induced HCC as being at higher risk of disease progression or death, although no significant difference was observed in terms of OS.

Several preclinical studies have reported potential beneficial effects of statins in models of advanced chronic liver disease, including a reduction in oxidative stress, enhancement of liver sinusoidal endothelial function, maintenance of hepatic microvascular integrity, and attenuation of fibrogenesis18. Consequently, in recent years, there has been a rapidly growing interest in the use of statins for the prevention and treatment of cirrhosis19. Regarding cirrhosis prevention, Wu and colleagues, in a large propensity score-matched retrospective study, demonstrated a dose-dependent protective effect of various statins in reducing the risk of decompensated cirrhosis among patients with type 2 diabetes20. These findings were further supported by a large retrospective analysis using UK Biobank data from over 1.7 million individuals, which reported that regular statin use was associated with a 15% reduction in the risk of new-onset liver disease and a 28% decrease in liver-related mortality21. Although several retrospective studies and meta-analyses have suggested that statins may confer survival advantages in cirrhotic patients, including a reduced risk of hepatic decompensation, acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), infections, and mortality4,22,23,24,25, these findings have not been confirmed in recent RCTs. Specifically, atorvastatin (10–20 mg/d) did not reduce liver-related complications and mortality compared to placebo in multicenter double-blind RCTs on adults with cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension26. Further uncertainties arose from the recent LIVERHOPE trial, which randomized 237 patients with decompensated cirrhosis (either in Child–Pugh Class B or C) to receive simvastatin (20 mg/d) and rifaximin (1200 mg/d) or placebo, showing that active therapy did not significantly impact the incidence of ACLF, liver-related complications, and mortality27.

The pleiotropic antitumor effects of statins in HCC stem from the inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis via the mevalonate pathway, which suppresses tumor proliferation, enhances immune surveillance by increasing T-cell infiltration, and reduces immune evasion mechanisms, creating a more favorable setting for HCC treatment28. Furthermore, statins exert important antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-angiogenic properties, further increasing their alleged anticancer effects, which might be dose-dependent and more pronounced with lipophilic molecules10. Based on these preclinical findings, it is reasonable to suggest that statins could play a role in both the prevention and treatment of HCC. However, while statin therapy has been associated with a reduced incidence of HCC and may help lower recurrence rates in patients undergoing surgical resection or liver transplantation29,30, their role in the treatment of advanced HCC remains a matter of debate. Han and colleagues reported that statin and TKI coadministration conferred a significant survival benefit in a propensity score matched population as compared to TKI alone, which seemed to be maintained even after TKI discontinuation31. Other trials, however, showed that pravastatin in combination to Sorafenib was not associated with a significant improvement in survival respect to Sorafenib alone32,33. By contrast, evidence about the clinical effect of statin and ICIs coadministration in advanced HCC are still lacking. Only one multicenter retrospective study has recently tried to address this issue: among the overall cohort of 730 patients, statin use did not confer any survival benefit either in patients treated with A + B or in those receiving Lenvatinib34. Interestingly, the discrepancy between observational studies, suggesting a protective role of statins, and RCTs, failing to confirm these findings, raises questions about potential confounding factors, selection bias, or differences in patient populations. However, the relatively short duration of some RCTs may have limited their ability to capture long-term benefits associated with statin use. Our study largely confirms the findings of Rimini and colleagues demonstrating that statins, when associated with immunotherapy, did not significantly reduce the risk of disease progression, death or treatment discontinuation due to liver-related events in advanced HCC patients questioning their real clinical utility in this setting34. Our study was not specifically designed to assess the impact of statins on portal hypertension-related complications during immunotherapy; however, the absence of a significant difference in liver-related treatment discontinuation and mortality between statin users and non-users suggests that statin therapy may not confer a clear protective effect in this context. Future studies specifically investigating the evolution of portal hypertension and its clinical manifestations—such as ascites, variceal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy—are warranted to better elucidate this potential benefit.

According to preclinical models, due to a different tumor microenvironment and an aberrant T cell activation which limits immune surveillance in MASLD-induced HCC, it has been supposed that immunotherapy might be less effective in these patients35. To support this hypothesis two large real-world studies have demonstrated that Lenvatinib conferred a significant survival benefit compared to A + B in metabolic related HCC whereas immunotherapy was more effective in patients with viral etiology36,37. On the other hand, another recent retrospective study of 412 patients found a trend towards a greater survival benefit in MASLD-HCC patients treated with A + B compared to those receiving Lenvatinib. More interestingly, the authors showed that patients with alcoholic-induced HCC treated with A + B had significantly worse prognosis compared to those receiving Lenvatinib or to patients with other etiologies, including MAFLD38. This is of great relevance, given the limited data on the prognosis and therapeutic response of alcohol-induced HCC. Interestingly, in our cohort, MASLD-induced HCC exhibited worse PFS compared to the other etiologies (both viral and alcoholic) with a trend, although not statistically significant, towards worse OS. This association remained significant even after propensity score matching, suggesting that the negative prognostic impact of MASLD may not be fully explained by baseline differences and could reflect a differential biological behavior or treatment response. While these results do not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that MASLD patients have a worse prognosis under A + B, they confirm that the etiology of HCC may play a significant role in determining treatment response and prognosis and indicate that this issue remains far from resolved requiring further investigation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of statins and ICIs coadministration on hard clinical endpoints in a prospective, multicenter cohort of advanced HCC patients. Real-world data enhanced the generalizability and validity of our findings, while PSM analysis allowed us to balance the two groups for potential confounders such as tumor burden, disease manifestations, extension, and metabolic comorbidities, further corroborating our results.

However, we must acknowledge that our study is not without limitations: (a) the relatively short follow-up period may have limited our ability to detect potential long-term effects of statin therapy; (b) the relatively small sample size, due to the low number of patients on statin therapy, frequently under prescribed in cirrhosis, may have affected the statistical power of survival analyses, preventing us from identifying significant differences between the two groups; (c) the lack of biochemical data about the lipid profile made it difficult to determine whether patients were receiving statins in accordance with current guidelines39; (d) data on the specific class of drugs (hydrophilic vs. lipophilic), dosages and treatment duration were lacking, preventing meaningful subgroup analyses to determine whether their anticancer effect might depend on these variables; (e) the higher prevalence of liver cirrhosis may have negatively impacted the overall survival analysis; (f) the analysis according to HCC-etiology must be interpreted with caution giving the fact that heavy alcohol drinking can be frequently underrecognized in metabolic patients with the consequent risk of misclassification in HCC etiology40.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that statin administration did not improve OS or PFS, nor did it reduce the risk of treatment discontinuation due to liver-related events in patients with advanced HCC receiving A + B. Interestingly, MAFLD-induced HCC appeared to be at higher risk of disease progression or death compared to the other etiologies. However, it remains to be clarified whether this is due to a lower effectiveness of A + B in these patients. Further studies in larger patient cohorts, accounting for statin type (lipophilic or hydrophilic), dosage, treatment duration, and circulating cholesterol levels, are needed to determine whether statins could have clinical utility as adjuncts to systemic therapy for advanced HCC. Moreover, robust randomized and/or prospective studies specifically accounting for the different etiologies of HCC are needed to determine how they can influence treatment efficacy and impact patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access data storage at the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona.

Abbreviations

- A + B:

-

Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- ALD:

-

Alcoholic liver disease

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- ECOG-PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IGF:

-

Insulin-like growth factor

- MASH:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

- MASLD:

-

Metabolic associated steatotic liver disease

- MELD:

-

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- MetALD:

-

Metabolic-alcoholic liver disease

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed-death-1 ligand

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PVT:

-

Portal vein thrombosis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SVR:

-

Sustained virological response

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial grow factor

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68(6), 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Vaughan, C. J., Gotto, A. M. & Basson, C. T. The evolving role of statins in the management of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 35(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00525-2 (2000).

Kuzu, O. F., Noory, M. A. & Robertson, G. P. The role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 76(8), 2063–2070. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613 (2016).

Kim, R. G., Loomba, R., Prokop, L. J. & Singh, S. Statin use and risk of cirrhosis and related complications in patients with chronic liver diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15(10), 1521-1530.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.039 (2017).

Postow, M. A., Callahan, M. K. & Wolchok, J. D. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 33(17), 1974–1982. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358 (2015).

Voron, T. et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8++ T cells in tumors. J. Exp. Med. 212(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20140559 (2015).

Cheng, A. L. et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 76(4), 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030 (2022).

Piscaglia, F. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: interim analysis results from the phase IIIb AMETHISTA trial. ESMO Open. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.104110 (2025).

Storandt, M. H. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as first-line systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A multi-institutional cohort study. Oncologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyae142 (2024).

Wang, J., Liu, C., Hu, R., Wu, L. & Li, C. Statin therapy: A potential adjuvant to immunotherapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1324140 (2024).

Shao, W. Q. et al. Cholesterol suppresses AMFR-mediated PDL1 ubiquitination and degradation in HCC. Mol. Cell. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-024-05106-w (2024).

Cao, R., Zhang, S., Ma, D. & Hu L. Angiogenesis inhibition combined with bevacizumab for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 241(7) (2017).

Reig, M. et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 76(3), 681–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018 (2022).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 79(6), 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003 (2023).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer. 45(2), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 (2009).

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r- proje ct. org/.

Ho, D., Imai, K., King, G. & Stuart, E. A. MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J. Stat. Softw. 42, 1–28 (2011).

Bosch, J., Gracia-Sancho, J. & Abraldes, J. G. Cirrhosis as new indication for statins. Gut. 69, 953–962 (2020).

Sharpton, S. & Loomba, R. Emerging role of statin therapy in the prevention and management of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and HCC. Hepatology 78(6), 1896–1906 (2023).

Szu-Yuan, Wu. et al. Protective effects of statins on the incidence of NAFLD–related decompensated cirrhosis in T2DM. Liver Int. 43(10), 2232–2244 (2023).

Vell, M. S. et al. Association of statin use with risk of liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver-related mortality. JAMA Netw. Open. 6(6), E2320222. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20222 (2023).

Bang, U. C., Benfield, T. & Bendtsen, F. Reduced risk of decompensation and death associated with use of statins in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. A nationwide case-cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 46(7), 673–680 (2017).

Kaplan, D. E. et al. Effects of hypercholesterolemia and statin exposure on survival in a large national cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 156(6), 1693-1706.e12. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.026 (2019).

Motzkus-Feagans, C., Pakyz, A. L., Ratliff, S. M., Bajaj, J. S. & Lapane, K. L. Statin use and infections in Veterans with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 38(6), 611–618 (2013).

Mahmud, N. et al. Statin exposure is associated with reduced development of acute-on-chronic liver failure in a Veterans Affairs cohort. J. Hepatol. 76(5), 1100–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.12.034 (2022).

Kronborg, T. M. et al. Atorvastatin for patients with cirrhosis. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000332 (2023).

Pose, E., Jiménez, C., Zaccherini, G., et al. Simvastatin and rifaximin in decompensated cirrhosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Published online 2025.

Chen, Y. & Wong, C. C. L. The mechanistic insights behind the anticancer effects of statins in liver cancer. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000519 (2024).

Yang, S. Y. et al. Statin use is associated with a lower risk of recurrence after curative resection in BCLC stage 0-A hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07796-7 (2021).

Cho, Y., Kim, M. S., Nam, C. M. & Kang, E. S. Statin use is associated with decreased hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in liver transplant patients. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38110-4 (2019).

Han, J. E. et al. The impact of statins on the survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sorafenib or lenvatinib. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020249 (2024).

Jouve, J. L. et al. Pravastatin combination with sorafenib does not improve survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 71(3), 516–522 (2019).

Blanc, J. F. et al. Phase 2 trial comparing sorafenib, pravastatin, their combination or supportive care in HCC with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. Hepatol. Int. 15, 93–104 (2021).

Rimini, M. et al. Impact of metformin, statin, aspirin and insulin on the prognosis of uHCC patients receiving first line Lenvatinib or Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70928-z (2024).

Pfister, D. et al. NASH limits anti-tumour surveillance in immunotherapy-treated HCC. Nature 592(7854), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03362-0 (2021).

Casadei-Gardini, A. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A large real-life worldwide population. Eur. J. Cancer. 180, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.017 (2023).

Rimini, M. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus lenvatinib or sorafenib in non-viral unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: An international propensity score matching analysis. ESMO Open. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100591 (2022).

de Castro, T. et al. Atezolizumab/bevacizumab and lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: A comparative analysis in a European real-world cohort. Hepatol. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000562 (2024).

Mach, F. et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020(41), 111–188 (2019).

Staufer, K. et al. Ethyl glucuronide in hair detects a high rate of harmful alcohol consumption in presumed non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 77(4), 918–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.04.040 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Alice Giontella for kind participation in the statistical analysis. Collaborators of the Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab and other immunotherapies real-life experience for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (ARTE) study group: Federico Ravaioli, Maria Boe, Sara Ascari (Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy); Anna Perna (Medical Oncology Unit, Ospedale del Mare, Napoli, Italy); Maria Elena Bellucco (Unit of General Medicine C and Liver Unit, Medicine Department, University of Verona and Hospital Trust (AOUI) of Verona, Verona, Italy); Chiara Scorzoni, Giulia Scandali (Liver Injury and Transplant Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria delle Marche, Ancona, Italy), Elisa Pellegrini (Medical Oncology Unit of Careggi Hospital).

Funding

Milella_PNRR-MAD-2022-12375670 CUP: E33C22000990006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

A.D. conceived the original idea for the study and contributed to the study design. F.T. conceived the original idea for the study and contributed to the study design; performed the statistical analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. F.C. wrote and reviewed the manuscript; performed the statistical analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data. LA. N. and M.V. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Giuseppe Cabibbo has served on in advisory board and received speaker fees for Bayer, Eisai, Ipsen, and AstraZeneca, MSD, Roche, Gilead. Ciro Celsa received speaker fees for AstraZeneca, EISAI, MSD, Ipsen, and received grants from Roche. Andrea Dalbeni is a consultant for Roche, Astrazeneca, Eisai, MSD. Support for congress attendance from Roche, Astrazeneca, Eisai, MSD. Massimo Iavarone in advisory board and received speaker fees for Gilead Sciences, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Roche, Roche Diagnostics, EISAI, IPSEN, MSD. Tiziana Pressiani received/reports consulting fees from Bayer, Ipsen and Astra Zeneca; institutional research funding from Roche, Bayer, Astra Zeneca.; support for congress attendance from Roche. Lorenza Rimassa reports receiving grant / research funding from AbbVie, Agios, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Fibrogen, Incyte, IPSEN, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, MSD, Nerviano Medical Sciences, Roche, Servier, Taiho Oncology, TransThera Sciences and Zymeworks. Consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Basilea, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Elevar Therapeutics, Exelixis, Genenta, Hengrui, Incyte, IPSEN, IQVIA, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, MSD, Nerviano Medical Sciences, Roche, Servier, Taiho Oncology and Zymeworks. Lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Guerbet, Incyte, IPSEN, Roche and Servier. Travel expenses from Astra Zeneca. Francesca Romana Ponziani received speaker fees, advisory board fees and travel grants from Bayer, MSD, Roche, Eisai, Ipsen, Astra-Zeneca, Gilead, Abbvie. Caterina Soldà reports consulting/advisory role for MSD and EISAI; speakers’ bureau for Roche and MSD. Francesco Tovoli is a consultant for Roche, Astrazeneca, Eisai. Caterina Vivaldi CV reports consulting or advisory role for Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, EISAI, Incyte, MSD, Roche, Servier, Taiho Oncology. All the other authors do not report any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dalbeni, A., Cattazzo, F., Vicardi, M. et al. Statins and clinical outcomes in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab. Sci Rep 15, 41844 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25752-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25752-4