Abstract

To investigate the coupled effects of cable corrosion on the ultimate strength and fatigue performance of cable-stayed bridges, sophisticated numerical simulations incorporating established corrosion mechanisms were conducted. Corrosion-induced degradation was modeled through cross-sectional area reduction and material property deterioration, with specific emphasis on wire elongation capacity attenuation. Three finite element models representing steel cable-stayed bridges with distinct spans (300 m, 600 m, and 900 m) were subjected to progressive collapse analysis and fatigue assessment. The results indicate that: (1) Structural failure consistently manifested through plastic hinge formation and fracture at the mid-span girder across all models, accompanied by partial plastification at the tower base; (2) Increased span length elevated cable stress at failure, thereby amplifying the influence of cross-sectional area reduction on ultimate strength; (3) Reduction of wire elongation rate from 4% to 3% or 2% resulted in marginal ultimate strength reductions, whereas attenuation to 1% induced precipitous capacity decline; (4) Under concurrent minimum cable area and elongation rate conditions, the ultimate load-bearing capacity of all bridge configurations experienced an approximate 50% reduction; (5) Corrosion significantly compromised fatigue performance at all cable positions, with localized pitting corrosion exacerbating stress concentration effects and accelerating cross-sectional degradation, consequently diminishing fatigue life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cable-stayed bridges, celebrated for their aesthetic elegance and structural efficiency in spanning vast distances, constitute vital arteries within modern transportation infrastructure1. Their structural integrity is paramount, underpinning economic vitality and public safety. Central to this integrity are the stay cables-high-strength tension members that transmit the deck load to the pylons, defining the bridge’s global stiffness and stability2. However, these critical components operate in a perpetually hostile environment. Continuously exposed to fluctuating environmental conditions (humidity, chlorides, pollutants, temperature cycles)3 and relentless cyclic stresses induced by traffic and wind, stay cables face an insidious threat: corrosion4. Documented evidence globally reveals an alarming trend of accelerated cable corrosion, culminating in catastrophic consequences. Notable bridge failures and near-collapses starkly illustrate that corrosion is not merely a maintenance concern but a fundamental threat to structural safety and service life, potentially leading to progressive collapse mechanisms5. This pervasive problem demands urgent and comprehensive scientific investigation. Corrosion damage in stay cables manifests through complex, interacting degradation pathways, far exceeding simple cross-sectional area reduction6.

Pitting corrosion and uniform section loss directly diminish the cable’s load-bearing area, fundamentally reducing its axial capacity. The corrosive environment initiates detrimental physico-chemical processes at the microstructural level. Hydrogen embrittlement (particularly in high-strength steels)7, stress corrosion cracking, and the general deterioration of the steel microstructure lead to a significant and often non-linear reduction in: (1) toughness and ductility8: the material’s ability to absorb energy and deform plastically before fracture is severely compromised, increasing susceptibility to brittle failure, especially under dynamyic or impact loads; (2) ultimate tensile strength and yield strength9: the maximum stress the cable can withstand and its elastic limit decrease, lowering the reserve capacity against overloads; (3)fatigue strength limit10 corrosion pits act as potent stress concentrators, drastically reducing the threshold stress range below which fatigue cracks will not initiate or propagate. The fatigue crack initiation life is significantly shortened, and the crack growth rate is accelerated due to the synergistic interaction of cyclic stress and the corrosive environment; (4) interfacial degradation: corrosion products (rust) within the strand bundle increase inter-wire friction and can disrupt load transfer mechanisms11, potentially leading to localized stress concentrations and uneven load distribution among wires12.

Consequently, the residual strength and, critically, the fatigue life of a corroded cable become highly unpredictable and significantly lower than its pristine counterpart. It is now widely recognized that in-service cable fractures predominantly result from the synergistic interplay between corrosion damage (acting as an initiator and accelerator) and the repetitive tensile stress fluctuations caused primarily by vehicular traffic13. This corrosion-fatigue interaction represents the dominant failure mode for aging stay cables.

The failure of a single stay cable, or more critically, the progressive failure of multiple cables, triggers complex force redistribution and potential instability within the highly indeterminate cable-stayed bridge system. Understanding this system-level response is crucial for risk assessment, remaining life prediction, and defining inspection/maintenance strategies. Significant research efforts have been directed toward this complex problem. Nazarian et al.14 examined the influence of factors such as the number of cables and main-span length (with varying side-to-main span ratios) on cable forces and ultimate capacity. Yan et al.15 analyzed the effects of fatigue fractures in different cables on structural buckling safety factors and stress states. Zhu et al.16 identified failure-prone cable locations and elucidated the full-process failure mechanisms of cable-stayed bridges based on defect data, further conducting structural vulnerability analyses. Zhu et al.17 investigated cable damage impacts on mechanical performance, concluding that static responses depend solely on damage location and severity, not failure sequence. Weik et al.18,19 established a probabilistic fatigue damage model to assess impacts on structural safety and system reliability. Li et al.20 proposed a time-dependent reliability analysis method considering coupled damage modes, evaluating corrosion-fatigue interactions on in-service cable performance.

In synthesizing the current body of research, it is evident that investigations into corrosion damage characteristics and failure mechanisms of stay cables have largely adopted compartmentalized approaches. Predominant methodologies isolate specific influencing factors-such as localized environmental aggressivity or operational stress regimes, to delineate discrete corrosion pathways21. While these studies have successfully characterized fundamental degradation processes (e.g., pitting initiation, stress corrosion cracking) and quantified structural performance penalties under prescribed corrosion levels, they exhibit critical limitations in addressing the inherent systemic interdependencies governing real-world cable-stayed bridge behavior. Crucially, cable-stayed bridges manifest substantial heterogeneity across multiple design dimensions: span configurations, material systems (composite vs. steel girders, concrete vs. steel pylons), cable arrangement philosophies (harp, fan, semi-fan layouts), and tensioning methodologies (initial prestress levels, tensioning sequences)22. This intrinsic variability induces complex, structure-specific interactions between corrosion damage and global structural response-interactions that cannot be extrapolated from isolated component-level studies or uniform bridge archetypes. In conclusion, most studies focus solely on the impact of corrosion on static performance, lacking a systematic analysis of fatigue life. Few simultaneously consider the dual effects of cross-sectional loss and material ductility degradation. There is a lack of comparative studies across different span lengths.

To transcend these limitations and holistically capture structural diversity, this research employs a parametric framework founded on three validated finite element models (FEM) of steel cable-stayed bridges, distinguished by their main span lengths: 300 m (representative of medium span), 600 m (long span), and 900 m (super-long span). This multi-model method enables system-level ultimate capacity & collapse path analysis: progressive static loading protocols are applied to determine the ultimate strength of each intact bridge system. More significantly, this methodology reveals the sequential collapse mechanisms triggered beyond the elastic limit, providing insight into structural redundancy and failure modality dependence on span scale; (2) corrosion-impaired ultimate strength assessment: corrosion damage is explicitly simulated via stochastic cross-sectional area reduction across cable elements, accounting for both uniform loss and localized pitting severity. This quantifies the residual ultimate strength of the corroded system and elucidates the global structural impact relative to pristine conditions. (3) fatigue life degradation under corrosion-stress synergy: the corrosion-fatigue interaction is investigated by integrating empirical corrosion-induced fatigue strength reduction factors with location-specific stress spectra derived from dynamic traffic analysis8. Cable-stayed bridges are cable-supported structures where cables are the primary load-carrying components; their corrosion has a decisive impact on structural safety. As an initial stage in a series of studies, this work focuses on the most sensitive component, laying the groundwork for subsequent full-system bridge analysis. This quantifies the accelerated fatigue life reduction of corroded cables at critical positions (e.g., mid-span, pylon anchorage zones) across the three span configurations, directly addressing the coupled deterioration mechanism most prevalent in service.

Bridge model parameters

Girder configuration

To examine cable corrosion effects on ultimate strength and fatigue life while accounting for span variability, three cable-stayed bridge models featuring identical girder cross-sections with main spans of 300 m, 600 m, and 900 m were designed. The girder cross-section, detailed in Fig. 1, maintained a flange width of 22.0 m and a web height of 3.0 m, as detailed in Fig. 1. Key material properties include: model-300, with the yield strength of the girder equal to 235 MPa; model-600, with the yield strength of the girder equal to 315 MPa; model-900, with the yield strength of the girder equal to 450 MPa. The elastic modulus of all steel materials is taken as 206 GPa.

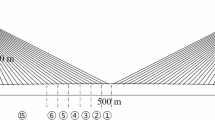

As shown in Fig. 1(a), for the Model-300, with a span of 300 m, 7 cables (#C1-C7) are distributed along the end span at 20 m intervals, and 7 cables (#C8-C14) are arranged in the left portion of the main span; for the Model-600 (600 m span), 13 cables (#C1-C13) are distributed along the end span at 20 m intervals, and 15 cables cables (#C14-C28) are arranged in the left portion of the main span; for the Model-900 (900 m span), 19 cables (#C1-C19) are distributed along the end span at 20 m intervals, and 22 cables cables (#C20-C41) are arranged in the left portion of the main span. The tensile strength of the stay cables is 1570 MPa.

Design load

The design load of a cable-stayed bridge consists of four parts: cable force (Pr), dead load (D), counterweight (CW ), and live load (L). The weight per unit length of the bridge (D) consists of three parts: the weight of the steel beam (69.7 kN/m), the weight of the ground cover (24.5 kN/m), and the deck pavement (28.4 kN/m). A counterweight load (60 kN/m) was applied at the side span to suppress the reaction force at the support.

The application of the cable force makes the bending moment of the main girder and the bridge tower under the dead load tend to be stable and minimized. The live load in the design load is taken as the concentrated load P1 (10 kN/m2) acting in the range of 10 m in length and 5.5 m in width, and the force of the other parts is 5.0 kN/m2. In addition, the uniform load P2 (3.5 kN/m2) acts on the area with a width of 5.5 m, and the load on the other parts is 5.0 kN/m2. The concentrated load is applied to the mid-span, and the uniform load acts on the full span.

Ultimate strength of cable-stayed Bridge model

Model establishment

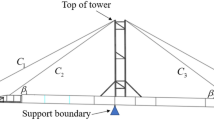

The three-dimensional frame analysis model depicted in Fig. 2 was developed using the finite element method, with nodes strategically positioned at cable anchorage locations of the main girder and tower. By established modeling practices for parallel wire cables, cables were simulated through equivalent circular cross-section bar elements matching the total cross-sectional area. Each cable element was discretized into 10 circumferential segments and 10 longitudinal segments, exclusively assigned tension-only properties. The analysis intentionally neglected both cable self-weight sag effects and geometric nonlinearity. Based on Saint-Venant’s Principle, changes in local boundary constraints primarily affect the stress concentration near the anchorage zone, while having a negligible impact on the axial stress distribution along the cable away from the anchorage. Although cables were modeled with rigid connections to the main girder and tower, their minimal bending stiffness exerted negligible influence on global structural behavior. In the model, the use of the Ernst formula to modify the elastic modulus approximates the sag effect23. The applicable scope of the current model, and note that employing more sophisticated cable elements for precise calculation of cable vibration or nonlinear response under extreme conditions will be a direction for future work.

The detailed dimensional annotations are shown in Fig. 1.

Model validation

According to reference24, for a baseline model with a 300-meter span, the results for girder deflection and cable forces under dead load were compared with simplified analytical solutions based on the cable theory. The errors between the two were within 7%, indicating the model’s reliability in terms of overall stiffness. The results are shown in Table 1.

Calculated results analysis

According to the design load in "Design load " the structural displacement of different span models is calculated. As shown in Fig. 3, the three cable-stayed bridges with different spans all show a large deflection in the middle span and a small deflection in the side span. The main bridge towers on both sides are inclined to the central span, and the deformation is symmetrically distributed.

Table 2 lists the section internal force and stress calculation values of the three models. Among them, there is a negative bending moment at the main beam of the main tower section, and the mid-span section of the main beam is the position with the largest positive bending moment. At the bottom of the main tower, there is a large axial pressure and bending moment. The ratio of allowable stress to calculated stress of each span cable-stayed bridge model under design load is greater than the safety factor, to determine the effectiveness of different span models. At the same time, according to the boundary conditions of the main tower, 0.7 times the height of the main tower is regarded as the effective buckling length when calculating the allowable stress of the main tower.

After determining the structural effectiveness of the cable-stayed bridge model under the design load, the ultimate strength of the cable-stayed bridge model with different spans is calculated. First, the cable prestress (Pr) is applied, and then the dead load and live load (D + L) are gradually increased. The expression of the applied load is as follows :

Where k is the loading coefficient and increases in 0.01 units until the model bridge collapses. The k at the end of the collapse is taken as the ultimate load coefficient, ku. According to the deformation of Model-300 under ultimate strength, the main girder has obvious deformation at the mid-span position. It can be seen from the curvature change curve that when the loading coefficient k = 1.8, the main beam yields, and then the structural curvature increases rapidly. When the loading coefficient k = 2.52, the plastic hinge is formed at the mid-span position of the main beam, and then the displacement calculation diverges. It can be seen from the stress-strain curve of the anchor span C1 cable that the C1 cable has entered the plastic stage but has not yet yielded. The cable at the mid-span is the same as the anchor span C1, and the steel plate at the bottom of the main tower has yielded.

Figure 4 shows the deformation of the Model-600, when it reaches the ultimate strength. The main girder also undergoes significant deformation at the mid-span position. When the loading coefficient k = 2.4, the main girder at the mid-span position yields. The loading coefficient is significantly larger than the Model-300, and the curvature increases rapidly after the main girder yields. When k = 2.77, the plastic hinge is formed at the mid-span position, and the analysis is terminated. Compared with the cable of Model-300, the C1 cable of Model-600 finally yielded, but did not reach the fracture strain. The bottom of the main tower was the same as that of Model-300, and some steel had yielded, and the structure was plasticized.

The mid-span girder of Model-900 also undergoes significant deformation in the limit state. From the curvature of this point, the mid-span girder yields at k = 2.5, which is not much higher than that of Model-600. After that, when k = 2.82, the section of the girder is completely plasticized, the displacement diverges, and the analysis ends. The C1 cable on the anchor span side has also yielded with Model-600 but has not yet broken. Based on the above comparison, it can be seen that the three model bridges all cause structural damage due to the plasticization of the mid-span main girder, but the cable stress of Model-300 still has a certain stress margin, and the cable of other models has reached its corresponding material strength limit, which will also increase the impact of cable corrosion on long-span cable-stayed bridges.

Effect of cable corrosion on ultimate strength and fatigue life

Influence of cable corrosion on ultimate strength

After completing the ultimate strength analysis of the normal cable-stayed bridge model, this section simulates the reduction of cable cross-sectional area and tensile rate caused by corrosion, and determines the influence of cable corrosion on the ultimate strength of the structure through elastic-plastic analysis. The corrosion scenarios analyzed represent discrete, severe states of deterioration at a specific point in time (or after a long service period), not a continuous process. The study employs a deterministic, comparative framework to quantify the mechanical impacts, serving as a foundation for future research. Time-dependent progression and probabilistic variation are indeed critical aspects for real-life prognosis and will be the focus of our subsequent research, where we plan to employ time-variant reliability analysis and stochastic modeling techniques based on the insights gained from this study.

Firstly, it is determined that the reduction rate of cable cross-sectional area under different corrosion conditions is 5%, 10%, 15% and 20%, and the elongation of normal steel wire constituting the cable is 4.0%. Corrosion will reduce the elongation of steel wire to about half of that under normal conditions. Ma and Yu’s researches25,26 show that due to the contact between steel wires and the influence of the anchorage end, the elongation of corroded cables will be further reduced to 1/4 of that of normal cables. Based on the above considerations, the steel wire elongation of the corroded cable is determined to be 3.0%, 2.0% and 1.0%, aiming to isolate their individual and interactive effects on structural performance, and the ultimate strength of the corresponding span model bridge is analyzed. The parameters are indeed correlated in practical engineering; coupled parameters for time-variant reliability analysis will be adopted in future research. The analysis method is the same as the above, first applying the prestress of the cable (Pr), and then gradually increasing the dead load and live load (D + L). The analysis results are shown in Fig. 5.

In the case of the same elongation, with the increase of the cross-section loss rate of the cable caused by corrosion, the corresponding ultimate load coefficient ku of the cable-stayed bridge also decreases, but there are differences in the reduction range between the cable-stayed bridges with different spans. For every 10% increase in the cross-section loss rate of Model-300, the ultimate load coefficient decreases by 0.17, while the ultimate load coefficient of Model-600 and Model-900 models decreases by about 0.25. The difference in the magnitude of change is due to the influence of the cable stress margin of different span models during the damage described in "Ultimate strength of cable-stayed bridge model".

On the contrary, when the cross-section loss rate is the same, when the cable elongation decreases from 4% to 2%, the ultimate strength of different span models is basically not affected, but when the elongation decreases to 1%, the ultimate strength of different span cable-stayed bridge models will decrease sharply.

The ultimate strength of the model with the cross section of the cable reduced by 30% and the elongation reduced to 1%, and the ultimate load coefficient ku from Model-300 to Model-900 decreased by 1.45/2.52 = 0.57, 1.48/2.77 = 0.54, 1.52/2.82 = 0.53, respectively. The percentage of decrease is the same, which indicates that the decrease in elongation has a more significant effect on the ultimate strength than the increase in cross-section loss rate.

Effect of cable corrosion on fatigue life

The fatigue strength of the cable will affect the service life of the bridge, because the cable bears the repeated load caused by vehicle traffic. In addition, corrosion of the galvanized steel wire that makes up the cable reduces its fatigue strength, which in turn reduces the overall strength of the bridge and shortens its service life. The fatigue design load of long-span cable-stayed bridges depends on the span of the cable-stayed bridge and the situation of the vehicle. The main purpose of this paper is to compare the influence of cable corrosion in different span cable-stayed bridge models. Therefore, when calculating the fatigue life of the cable, the heavy vehicle with W = 500 kN, which is slightly smaller than the standard beam bridge, is set as a typical vehicle27. The typical vehicle load is applied to the three bridge models to determine the fatigue life before the cable breaks. Due to the complex structure and diversity of cable-stayed bridges, the fatigue life depends on the cable location, bridge span, corrosion level of galvanized steel wire, and other factors. This section will study how these factors affect the fatigue life of the cable. Actual corrosion processes exhibit significant randomness and time-dependency. The deterministic model employed in this study serves as a foundation for subsequent probabilistic time-dependent analysis.

Calculation of stress amplitude

By moving the unit load ( P = 1 kN ) over the entire span length, the influence line of the cable tension is obtained, and the stress amplitude of the cable is determined. Figure 6 shows the cable tension changes of four representative cables (anchor cable (C1), cable at the midpoint of side span, cable at the midpoint of main span, and cable at the midpoint of main span under the influence line loading in three different span models.

The distribution law of cable tension variation values of different span models is the same. The tension of the anchor cable (C1) reaches a negative peak at the side span and a positive peak at the main span. The cable tension at the midpoint of the side span reaches the maximum positive peak at the side span and reaches a smaller positive peak at the main span. The cable tension at the midpoint of the main span only has a positive peak at the main span position. For the cable at the mid-span position of the main span, the maximum negative peak is reached near the mid-span of the main span, and then the maximum positive peak is reached. These trends are the same in Model-600 and Model-900. Comparing the stress amplitude changes of the cables at different positions, it can be seen that the stress amplitude of the anchor cable (C1) is greater than that of the cables at other positions.

Corrosion of galvanized steel wire

The corrosion of galvanized steel wire is divided into three levels. Corrosion level 1 means that only the galvanized layer is corroded, while the substrate part is not corroded, and the strength is equivalent to that of healthy steel wire. Corrosion level 2 refers to the partial corrosion of the substrate under the galvanized layer. Corrosion level 3 refers to the state in which the corrosion of the substrate is further deepened and expanded. According to reference22, fatigue tests were carried out on these three corrosion levels of galvanized steel wires and healthy galvanized steel wires, and the S-N relationship obtained is shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that the fatigue strength decreases in the order of sound/corrosion level 1, corrosion level 2, and corrosion level 3. The S-N relationship of fatigue design corresponding to different corrosion levels is: Health and corrosion level 1: \(S{N^{1/5}}=6000\), corrosion level 2༚\(S{N^{1/5}}=4600\), corrosion level 3༚\(S{N^{1/5}}=3100\).

Results of fatigue life

Table 3 shows the fatigue life of the cable at different positions. The stress amplitude in the table is obtained by dividing the tension difference between the maximum and minimum peaks of the cable tension fluctuation shown in Fig. 7 by the cross-sectional area. When a typical vehicle load passes through the bridge, a maximum stress amplitude is generated, that is, the frequency meter is 1 cycle. According to the level of corrosion, the number of fracture cycles was calculated using the S-N relationship shown in Fig. 7.

Taking the anchor cable (C1) of Model-300 as an example, the fatigue life decreases significantly with the increase of corrosion level. The fatigue life of the anchor cable (C1) in corrosion level 1 is compared with other corrosion levels and other cables. It can be seen that the fatigue life of the anchor cable (C1) with corrosion level 3 is only 3.7% of that of corrosion level 1. Cables at other locations (C4, C10, and C14 ) also have a similar trend, and the fatigue life decreases significantly with the increase of corrosion level. However, the fatigue life of C4, C10, and C14 at corrosion level 1 is 80.7%, 12.0% and 12.0% of that of C1, respectively, which is mainly due to the difference in the shape of the cable tension influence line. The cable fatigue life of Model-600 and Model-900 shown in Table 2 has the same trend as that of Model-300, that is, the stress amplitude of the anchor cable is much larger than that of other positions, and the number of fractures is less than that of other cables. The fatigue life decreases rapidly with the increase in corrosion level.

Effect of corrosion on cross-sectional reduction

In the previous section, the fatigue life of the steel wire was analyzed only by considering the change of fatigue strength without considering the factor of cross-section reduction caused by corrosion. However, in practical applications, as the corrosion progresses, the local pitting corrosion of the cable will further develop, resulting in a decrease in the cross-sectional area. Therefore, this section focuses on the fatigue life of the cable under the condition of corrosion level 3, and the cross-sectional area of the steel is reduced by 0–20%.

Table 4; Fig. 8 show the fatigue life of different span cable-stayed bridges with the change of cross-section loss rate. It can be seen from the change curve that the decrease in cross-sectional area will lead to a significant decrease in fatigue life. The fatigue life of different span cable-stayed bridges is basically the same as that of the cross-section loss rate. When the cross-section loss rate is 10%, the number of fractures is reduced to 0.59 times when the cross-section loss rate is 0%, and when the cross-section loss rate is 20%, the number of fractures is reduced to 0.32 times. As the corrosion intensifies, local pitting corrosion leads to an increase in stress concentration, which further leads to a wider range of steel section consumption, thereby significantly reducing fatigue life.

Conclusions

In this study, a systematic method for coupled corrosion-fatigue analysis is established. First quantitative comparison of the relative importance of cross-sectional loss versus ductility degradation on the fatigue life of cable-stayed bridges, and the revelation of the scale effect of corrosion influence through three case studies with different spans, the main conclusions are as follows.

-

(1)

All bridge models failed when a plastic hinge formed at the mid-span girder, causing collapse. Partial yielding also occurred at the tower base. The ultimate load capacity increased from 2.41 to 2.82 as the span lengthened. Longer spans showed greater vulnerability to cable corrosion. Cables reached full material strength at failure in these models. For every 10% loss of cable cross-sectional area, Model-300’s load capacity decreased by 0.17, while Model-600 and Model-900 showed larger reductions of about 0.25 at equivalent material ductility.

-

(2)

Reducing cable ductility (elongation rate) from 4% to 3% or 2% caused minor strength losses. However, decreasing ductility to 1% reduced strength by up to 30%. When combined with maximum cross-sectional loss, capacity decreased by approximately 50% for all spans. Reduced material ductility thus impacts strength more severely than cross-sectional loss alone.

-

(3)

Cables at anchorage points endured higher stress fluctuations, shortening their fatigue life. Corrosion dramatically accelerated fatigue damage at all locations. Localized pitting corrosion concentrates stresses and amplifies section loss, further reducing fatigue resistance. While corrosion reduces the fatigue life of cables at all positions, the analysis reveals that cables near anchorage zones experience the most severe degradation and are therefore particularly critical for inspection and maintenance planning.

The stochastic process models will be adopted, and time-variant reliability theory will be used to deepen corrosion prediction research. Future research will extend the analysis to the corrosion effects on other components, such as the bridge deck and piers. The method of using a uniform assumption in this study serves as a conservative baseline case for mechanistic investigation, providing a benchmark for subsequent studies on non-uniform corrosion. The rigid anchorage assumption indeed cannot reflect the local stress state in the anchorage zone; therefore, the conclusions of this study do not apply to fatigue damage analysis of the anchorage components themselves.

Data availability

Data are provided within the manuscript.

References

Lu, W. G. et al. Effect of cable corrosion on nonlinear elastic stability of girder in cable stayed bridges with floating systems. Structures 37, 131–132 (2022).

Liu, N. W. et al. System reliability evaluation of in-service cable-stayed bridges subjected to cable degradation. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 14 (11), 1486–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/15732479.2018.1459743 (2018).

Rou, L. et al. Effect of environmental factors on electrochemical corrosion of galvanized steel wires for Bridge cables. Anti-Corros Methods Mater. 69 (1), 244–246 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. Temporal and Spatial variability of corrosion of high-strength steel wires within a Bridge stay cable. Constr. Build. Mater. 308, 211–213 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Investigation of shear bearing capacity of UHPC-NC connection structures in the negative bending moment zone of assembled beam bridges. Structures 71, 108091 (2025).

Janjic, D. et al. Optimization of cable tensioning in cable-stayed bridges. J. Bridge Eng. 8 (3), 131–137 (2003).

Damiani, M. et al. FRP cables to prestress RC beams: state of the Art vs. a split wedge anchorage system. Buildings 11 (5), 122–123 (2021).

Pei, B. et al. Design and key construction technology of steel-concrete-steel sandwich composite pylon for a large span cable-stayed Bridge. Sci. Rep. 13, 6626. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33316-7 (2023).

Liu, X. L. et al. Condition assessment model for cable stayed based on evidence reasoning framework. J. South. China Univ. Technol. (Nat Sci. Ed). 48 (6), 69–76 (2020). [in Chinese].

Zhang, Y. et al. Static performance of a long-span concrete cable-stayed Bridge subjected to multiple cable loss during construction. J. Bridge Eng. 25 (3), 1–16 (2020).

Ai, P. C. et al. Novel self-anchored CFRP cable system: concept and anchorage behavior. Compos. Struct. 263, 279281 (2021).

Hoang, V. et al. Experimental and numerical study of lateral cable rupture in cable-stayed bridges: case study. J. Bridge Eng. 23 (6), 5018004 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Bearing capacity of UHPC-NC connection structure in negative moment zone of PC beam bridges. Struct. Concr. 25 (5), 792–829 (2024).

Nazarian, E. et al. Detection of tension loss in cables of cable stayed Bridges by distributed monitoring of Bridge deck strains. J. Struct. Eng. 142 (6), 04016018 (2016).

Yan, D. H. et al. The influence of cable damage on the reliability of in-service cable-stayed Bridge systems. J. South. China Univ. Technol. (Nat Sci. Ed). 51 (01), 213–220 (2020). [in Chinese].

Zhu, J. et al. Prediction of fatigue life of cables in coastal long-span cable-stayed bridges under the combined action of random traffic flow and wind. Chin. J. Highw Transp. 33 (11), 182–194 (2020).

Zhu, J. et al. Probabilistic fatigue damage assessment of coastal slender bridges under coupled dynamic loads. Eng. Struct. 166 (7), 274–285 (2018). [in Chinese].

Wei, K. et al. Directional effects on the reliability of non-axisymmetric support structures for offshore wind turbines under extreme wind and wave loadings. Eng. Struct. 106 (1), 68–79 (2016).

Wei, K. et al. Effect of wind and wave directionality on the structural performance of nonoperational offshore wind turbines supported by jackets during hurricanes. Wind Energy. 20 (2), 289–303 (2017).

Li, C. G. et al. Innovative compound-type anchorage system for alarge-diameter pultruded carbon/glass hybrid rod for Bridge cable. Mat. Struct. 53 (1), 243–246 (2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Bridge cable damage identification based on acoustic emission technology: a comprehensive review. Measurement 237, 115195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115195 (2024).

Nakamura, S. et al. Hydrogen embrittlement and corrosion fatigue of corroded Bridge wires. J. Constr. Steel Res. 65 (2), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcsr.2008.03.022 (2009).

Wen, Y. et al. Qualification of the Ernst formula for modeling the sag effect of super-long stay cables in the long-span railway cable-stayed bridges, Structures 45: 99–109 DOI10.1016/j.istruc.2022.09.002. (2022).

Cukaci, C. E. et al. Vision-based identification of cable tensions and finite element model verification of a cable-stayed Bridge. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 5 (15), 1319–1335 (2025).

Ma, Y. F. et al. Vulnerability analysis of long-span cable-stayed bridges under cable damage. J. Chang’an Univ. (Nat Sci. Ed). 42 (06), 101–109 (2022). [in Chinese].

Yu, P. et al. A new method for testing the elongation of steel cable and wire rope after fracture. Phys Test. Chem. Anal. (Part A) 58 (09): 23–26 (2022)[in Chinese].

Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Specifications for Design of Highway Steel Bridge. JTG D64-2015 (China Communications, 2015).

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the 2024 key research project plan for higher education institutions in Henan province (24A560009).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, Z., Liu, Y., Xu, B. et al. Investigation of the impact of cable corrosion on the ultimate strength and fatigue life of stay cable bridges. Sci Rep 15, 41868 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25769-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25769-9