Abstract

Microscopy is an essential tool in scientific research, enabling the visualization of structures at micro- and nanoscale resolutions. However, the field of microscopy often encounters limitations in field-of-view (FOV), restricting the amount of sample that can be imaged in a single capture. To overcome this limitation, image stitching techniques have been developed to seamlessly merge multiple overlapping images into a single, high-resolution composite. The images collected from microscope need to be optimally stitched before accurate physical information can be extracted from post analysis. However, the existing stitching tools either struggle to stitch images together when the microscopy images are feature sparse or cannot address all the transformations of images when performing image stitching. To address these issues, we propose a bi-channel aided feature-based image stitching method and demonstrate its use on Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) generated Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm and PTO thin film sample images as experimental data. The topographical channel image of AFM data captures the morphological details of the sample, and a stitched topographical image is desired for researchers. We utilize the amplitude and phase channels of AFM data to maximize the matching features and to estimate the position of the original topographical images and show that the proposed bi-channel aided stitching method outperforms the traditional direct stitching approach in AFM topographical image stitching task. Here, we demonstrated the application on AFM, but similar approaches could be employed of optical microscopy with brightfield and fluorescence channels. We believe this proposed workflow can serve as a valuable augmentation strategy for microscopy image stitching tasks and will benefit the experimentalist to avoid erroneous analysis and discovery due to incorrect stitching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-resolution microscopy is a cornerstone of scientific discovery, providing unparalleled insight into the structure and function of materials and biological specimens. However, a fundamental challenge in microscopy is the trade-off between resolution and field of view (FOV). High-magnification imaging reveals fine structural details but captures only a limited portion of the sample at a time. This constraint is particularly problematic in fields requiring both fine-scale resolution and large-area context, such as histopathology, neuroscience, and materials science. For example, in medical diagnostics1,2,3,4, pathologists analyzing tissue biopsies must examine entire sections while still detecting subcellular abnormalities indicative of diseases like cancer. Similarly, in neuroscience5,6,7, researchers studying brain tissue and spinal cord must visualize intricate neuronal networks spanning large regions while preserving the details of individual synaptic connections. Beyond biology, disciplines like astronomy8,9 also face analogous challenges when stitching together high-resolution telescope images to create expansive sky maps. Similarly, to analyze geospatial data for predicting traffic conditions and optimizing transportation routes, large high-resolution satellite images need to be stitched together10,11,12,13. Here, seamless stitching of these high-resolution images is a crucial step to ensure (1) preservation of the physical insights of the original images and (2) avoiding potential false interpretation and discovery of the underlying information of the images. During the collection of these images, a degree of overlap between two adjacent images is set. If the degree is lower, the number of sampling images is reduced, which decreases the total scanning cost. While increasing the overlap, the data acquisition cost proportionally increases.

Over the years, various image stitching techniques have been developed to computationally merge multiple microscopy images into seamless, high-resolution composites. When applying image stitching techniques to microscopy images, researchers have primarily adopted two approaches: feature-based methods14,15,16,17,18 and Fourier-based methods19. Feature-based methods include feature detection, feature matching, camera pose estimation, warping and blending etc. In contrast, Fourier-based methods calculate the translational offsets between images using phase-correlation and then align the images based on these offsets. While Fourier-based techniques are straightforward and fast, they only address translational shifts, whereas feature-based approaches can handle additional transformations such as rotations and scaling. Existing feature-based stitching tools, such as AutoStitch20, stitch2D21 and Stitching22 are highly effective for stitching images with a high volume of matching features obtained from significant amounts of image overlapping. Ma et al. were among the first to apply a feature-based photography stitching software, AutoStitch20, to microscopy images23. Yang et al. proposed estimating the overlapping area between the images using phase correction, thereby narrowing the search space for feature detection24. This approach is faster than directly stitching using SURF25 and improves the accuracy of feature matching. However, it still requires images to have enough features since it does not increase the number of detected features as illustrated by the microscopy images with 50% overlap used to present their method. Mohammodi et al. employed SURF25 as the feature detector and utilized a weighted graph tree to replace camera pose estimation, reducing computational costs15. However, to maintain accuracy, they used microscopy images with a 30% overlap. Xu et al. proposes the enhancement of the features via image edge detection prior to applying SIFT algorithm26,27, to maximize the matching features28. However, the method does not address the challenges in microscopy images, when the matching features are sparse and unevenly distributed. Recently, Gan et al. proposes an optimized SIFT algorithm to address the issue of uneven feature point distribution in the image stitching process, however, the validation is limited to environmental pictures where significant features are available29. Preibisch et al. applied a Fourier-Shift Theorem in image stitching with translational variations, however this method does not account for the rotational variations that possibly occur during microscopy image acquisition30. MIST is another microscopy image stitching tool19, which aims for fast stitching but is limited to handle only translational variations due to relying on a similar Fourier-based approach. Moreover, MIST does not apply image blending and the stitched image usually introduces additional noises such as generating seam lines, which can affect the downstream image analysis. Recently developed neural network-based feature detection and matching algorithms, such as SuperGlue31 and LoFTR32, point in a new direction for image stitching. However, the current stitching tools based on these algorithms are limited to pairwise stitching and cannot process large volumes of images, which is essential in stitching microscopy images. Recent efforts are being made to improve stitching quality of images beyond significant overlapping. Seo et al. pushes the boundary to 1.15% overlap using a brightness-based normalized cross-correlation method33; however, this method can only be applied under the strong assumption that there’s no rotation or size scale when acquiring the images. Recently, a large-area AFM method has been developed by Millan-Solsona et al. to enable imaging of millimeter-sized biofilm structures34. However, the image stitch package stitch2D21 used shows limitations when it comes to feature sparse AFM images.

There is a need for an improved image stitching method that can accurately stitch complex and noisy microscopy images with limited overlap due to experimental constraints. Therefore, we propose a feature-based bi-channel aided approach to stitch limited overlapped microscopy images. This paper focuses on improving stitching tools for the registration of the stack of small-area and high-resolution microscopy images. While gradient-based techniques have previously been applied to improve image stitching, their primary focus has been on refining the visual quality of the stitched output. For instance, Gradient-Domain Image Stitching (GIST), developed by Anat Levin et al.35, utilizes image gradients during the blending stage to reduce visible seamlines after alignment. In contrast, our method aims to leverage image differentials at an earlier stage in the pipeline to enhance feature detection and improve the accuracy of image alignment, particularly in cases with limited overlap and sparse features. We demonstrate the proposed method by stitching Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) generated images of bacterial biofilms via first extracting higher number of matched features from different correlated microscopy imaging channels such as amplitude and then utilizing the information to estimate the alignment of the topographical images. Furthermore, we show that the differentiation of the topographical images along the x-axis provides similar feature information to the amplitude channel image, which generalizes our approach when the amplitude images are not available. We compared the performance of our method with other stitching approaches by experimenting with different biofilm datasets with 10% overlapping and thereby demonstrated the effectiveness of our method. By integrating the proposed workflow, our work aims to improve the balance between cost effective automated microscopy scanning and image stitching accuracy, enabling extraction of accurate physical information and promoting discovery.

Result and discussion

AFM techniques provide multi-channel information, offering various data streams that can aid in the image stitching process. In addition, the limited scan area of the device often necessitates capturing an array of overlapping images. These overlapping regions not only enable accurate stitching but also help mitigate common AFM artifacts. Among the most significant artifacts are sample tilt, rotation induced by the piezo drive, hysteresis, thermal drift, and the limited precision of the motorized stage. To ensure a reliable reconstruction, the stitching system must effectively compensate for these distortions while accounting for the degrees of freedom involved. Specifically, in AFM, image stitching must address sample displacement, rotation, and tilt to achieve accurate alignment and seamless integration.

Proposed approach of feature-based bi-channel aided image stitching of microscopy images. Here fig. (a) shows the traditional direct stitching of stack of overlapped microscopy topographical images where (b) shows the stitching of the same via our proposed approach. Here in our method, we extract higher matched features (denoted by green lines) from correlated second channel microscopy images (e.g. stack of overlapped amplitude or differential images) than extracting matched features directly from the first channel topographical images as in (a). Then, we utilize the insights from a higher number of matched features to improve the camera pose estimation and thereby improve the stitching quality of the topographical images.

In this paper we propose a bi-channel aided microscopy image stitching method based on the underlying feature-based technique. By controlling the input in the feature-based image stitching pipeline, our goal is to obtain a more precise estimate of the rotation, displacement, and tilt variations of the sampled microscopy images by maximizing the extraction of matched features from the limited overlapping areas. Figure 1 shows the proposed workflow of bi-channel aided stitching method. In general, as shown in Fig. 1, feature-based stitching involves four key steps: feature detection, feature matching, camera pose estimation, and image warping and blending. In feature detection, distinct patterns or key points from all the scanned microscopy images are identified. Then, the feature matching algorithm extracts the corresponding key points from overlapping areas of adjacent images. In camera pose estimation, we estimate the intrinsic (i.e., focal length and principal point settings) and extrinsic parameters (i.e., rotation and translation) of the camera pose relative to a reference frame. Finally, the warping and blending algorithm applies the estimated image transformations to images and stitches them together seamlessly.

Following our proposed approach of bi-channel aided stitching (Fig. 1b), in this case study of bacterial surface attachment and biofilm formation, topographical images generated from large area-AFM are the sample of interest (first channel) as it captures the morphological details of the attached cells. However, instead of detecting features from topographical images (first imaging channel), we explore other AFM imaging channels that are correlated to the first imaging channel, revealing finer surface details and containing a higher number of detectable features. In this case, this exploration and analysis for identifying the second imaging channel is conducted via domain expert knowledge. Here, to choose the best second imaging channel for feature detection and matching, we find that amplitude images yield more detected and matched features, which enhance the performance in stitching compared to topographical image. To generalize our proposed approach, we aim to investigate other correlated imaging channels when the amplitude images are not available. To eliminate the need for the experimental and storage burden of amplitude images, we investigated further and found that computing the x-axis derivative of the topographical image (first channel) also yields similar feature-rich images like the amplitude images (second channel). Thus, in camera pose estimation, using the highly matched features of correlated microscopy second channel images (e.g. amplitude images), we estimate the parameters of the camera pose relative to a reference frame. Since the AFM images are not captured by any conventional camera, the camera pose parameters are treated as an assumed variable used to calculate image transformations. In this step, the algorithm first assigns initial values to the camera pose parameters, then optimizes those using the matched features. Here, these parameters are optimized and estimated from the higher feature-matched second channel such as amplitude channel, which are then used to determine the transformations of the first channel topographical images within a unified coordinate system. In image warping, we align the topographical images together by applying the derived transformation matrix to these images on a per-pixel basis. That is, we first perform feature detection, matching, and camera pose estimation using the second channel images (high featured), and then we apply the estimated transformations to warp the first channel images (sparse featured) together. Finally, the blending algorithm takes the warped topographical images and blends them together seamlessly. It should be noted that our method does not depend on the availability of only amplitude channel images. Rather, we see that the differentiation of the topographical images along the x-axis provides similar feature information to the amplitude channel image, which can be considered as the second channel when the amplitude image is not available. Considering the objectives of having high correlation between first and second channel images and higher detected/matched features of the second channel images, if no better solution is found, then the optimal second channel images is the first channel images.

For all the demonstrated analysis of the proposed approach, we considered the package “Stitching”, coded in Python22. Stitching provides a Jupyter notebook tutorial that allows us to use each stitching module flexibly. We integrate our idea with the stitching pipeline to perform the AFM topographical images stitching task. We use the amplitude image as input for feature detection. There are four feature detectors available from the Stitching package: ORB, BRISK, AKAZE and SIFT. After exhaustive tuning with different feature algorithms, we chose SIFT as the feature detector with contrast_Threshold = 0.015, edge_Threshold = 15. After extracting key features from all the amplitude images, these features are matched between image pairs using feature matching. There are two feature matching modes available: homography and affine. Affine transformations are computationally cheap and consider scaling, rotation and translation variations whereas Homography mode handles one more type of transformation named perspective distortion. However, as these transformations are unlikely to happen in microscopy images as per domain expert knowledge, we use the affine mode for better feature matching. To demonstrate the performance of the proposed method, we considered two datasets of large-area AFM scanned images of early biofilm formation, with each dataset being scanned at 10% overlap.

Discussion on experimental datasets

To validate our proposed approach, we have focused on the study of the early stages of bacterial biofilm formations, where the researchers must capture both the overall structural organization of microbial communities and the fine-scale interactions between individual cells, which are critical for understanding biofilm formation, resistance mechanisms, and responses to environmental changes. AFM36 has been considered for studying surface attachments it operates effectively in both air and liquid environments, allowing imaging under near physiological conditions37,38. Moreover, AFM provides high-resolution imaging and can generate detailed three-dimensional images of surface topography for studying cell structures, cell-to-cell interactions, and fine features like cell walls, flagella and pili39. AFM has not only proven to be a powerful tool for nanoscale mechanical and topographical characterization, but it also enables the integration of various non-invasive chemical imaging40,41 and composition mapping42, internal hydration properties of single bacterial endospores43 and properties of outer membrane extensions of bacteria44. While AFM can provide detailed insights into individual cells and bio-structures at the nano- to microscale and capture intricate details about the topography and mechanical properties, traditional AFM techniques are still limited by their slow measurement process and small imaging areas (typically < 100 μm) due to being restricted by piezoelectric actuator constraints, thereby limiting the use of AFM to study large, millimeter-scale biofilm structures. This scale restriction makes it challenging to gain a representative understanding of biofilm assembly across larger areas. In order to study the dynamic properties of the biofilm at different stages of formation, the collected large area AFM topographical images need to be stitched together to reconstruct the full image.

AFM images were acquired using the DriveAFM system from Nanosurf, which features a motorized platform capable of scanning large areas. The datasets were collected using the methodology described in34 through a custom Python graphical interface designed to capture image arrays. In this study, we utilized 3 × 3 and 7 × 7 overlapping image arrays, each image of 15 × 15 µm2 and 87 × 87 µm2 respectively with a 10% overlap. For the remainder of the paper, we correspond these to datasets 1 and 2, respectively. The stack of the images in datasets 1 and 2 is provided in Supplementary Materials (Fig. S1). All images were acquired in tapping mode, capturing topography, amplitude, deflection, and phase channels. AFM topographic images often contain noise, such as artificial horizontal lines caused by the feedback system, adhesion artifacts, or changes in resonance frequency, which result in abrupt variations between consecutive scan lines. Additionally, AFM measurements require post-processing to correct potential sample tilts, thermal drift, and other distortions. These artifacts can be easily removed using commonly applied techniques, such as mean difference adjustment, median adjustment, surface fitting methods, and flattening techniques. In this study, we used custom functions available in45 to integrate them into the workflow. The samples used in this studyto a time course of surface attachment by Pantoea sp. YR343, a Gram-negative bacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of poplar trees, known for its plant growth-promoting properties46. Pantoea sp. YR343 is a motile, rod-shaped bacterium with pili and peritrichous flagella, facilitating its interactions within its environment. The strain was grown in minimal medium, as described in34, on a silicon oxide substrate between 4 and 6 h for dataset 1 and for 30 min for dataset 2. At the time of collection, the coverslip was carefully rinsed in Nanopure water to remove unattached cells, without being allowed to dry at any point. The coverslips were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and washed once more. Finally, the samples were dried before imaging using pressurized nitrogen.

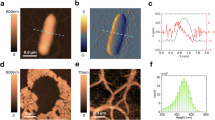

Before implementation, we also analyze the features of the topography and other imaging channels for these datasets. Table 1 shows the comparison of the detected and matched features among the topography, amplitude and the differential channels for both datasets. Figures 2 and 3 show the detected features among the topography and the other imaging channels for a sample image on both datasets respectively. From the figures, it is clear that the images from the amplitude and differential channels contain more features as denoted by the density of green dots.

Comparison of the detected features between the (a) topographical, (b) amplitude and (c) differential images of the Pantoea sp. YR343 dataset 2. Here, we present one sampled scan image from the dataset. Figures (d), (e) and (f) are the zoomed images at the box section provided in (a), (b) and (c) respectively. The green dots in each of the images are the detected features.

Case study 1-implementation on dataset 1 of Pantoea sp. YR343 sample

We first implemented our proposed approach of bi-channel aided image stitching to dataset 1 composed of images of early biofilm assembly by Pantoea sp. YR343, where the strain was grown on a silicon oxide substrate between 4 and 6 h. The dataset includes 9 scanned topographical and amplitude images, each image of 15 × 15 µm2 and acquired with a 10% overlap. From Table 1, we can see each topographical image yielded an average of 375 detected features, resulting in 6 matched image pairs with approximately 13 matched features per pair. In contrast, the corresponding amplitude images capture finer surface details, with each image averaging 2,736 detected features, this resulted in 12 matched pairs, with each pair averaging 169 matched features. Note that detecting a larger number of features not only improves image matching accuracy but also increases the number of matched pairs, leading to a more complete stitched image. In contrast, the differential images average 1,851 detected features, which is lower than the number of detected features in amplitude images, but significantly higher than the detected features in the topographical images. Even though the number of detected features in the differential images is lower than in the amplitude images, the average number of matched features in the differential images is 149, similar to the 169 matched features in the amplitude images. It should be noted that the stitching performance depends heavily on the matched features, and therefore, the differential images also provide significant key details like the amplitude images. Figure 4 provides a visual example of feature matching from the amplitude and topographical images (as denoted by green lines), where amplitude images show a significantlarger number of matched features.

Using the proposed bi-channel aided image stitching method (see Fig. 1), we estimated a transformation matrix from the amplitude images and applied it to the topographical images, resulting in a stitched topographical image. Figure 5 shows the stitching performance of the proposed method and the comparison with traditional approaches using existing algorithms such as Stitching, Stitch2D and MIST. Here, Stitching fails completely to estimate the camera pose and thus it could not provide any solution. From Fig. 5a, we can see Stitch2D can only partially stitch images with a 20% overlap where the blank rectangle region is the failed region in the image canvas where the method could not align any images due to potentially sparse matching features of the topographical images (see Table 1). Furthermore, Stitch2D fails to stitch any topographical images when the overlap decreases to 10%. MIST, on the other hand from Fig. 5b, performed better and could stitch topographical images with a 10% overlap when the overlap percentage is manually specified. However, the stitched topographical image introduced noises such as several seam lines (denoted by red and yellow solid boxes in Fig. 5d and e). These seam lines can interfere with subsequent post image analyses, such as image segmentation and object detection,. to study the physical properties of cells during biofilm assembly. Thus, even though MIST could be able to stitch all the images, the stitched image is physically undesired as per the domain experts. From Fig. 5c, we can clearly see our method outperformed the traditional approach where it can stitch all the topographical images with 10% overlap without generating any significant noise from stitching (denoted by red and yellow dotted boxes in Fig. 5d and e). Figure 6 shows the comparison of the stitched topographical image via extracting features from amplitude and differential images which are similar to the result using the amplitude channel images.

Stitching of Pantoea sp. YR343 dataset 1 images using different second imaging channel. Here, (a) is the stitched amplitude channel image, (b) is the stitched differentiation image, (c) is the stitched topographical image with aid of the amplitude image, (d) is the stitched topographical image with aid of the differentiation of topographical image along x axis.

Case study 2- implementation on dataset 2 of Pantoea sp. YR343 sample

Next, we implemented our proposed approach to the biofilm dataset 2 of Pantoea sp. YR343, where the strain was grown on a silicon oxide substrate for 30 min. The dataset includes 49 scanned topographical and amplitude images, each image of 87 × 87 µm2 and acquired with a 10% overlap. From Table 1, we can see each topographical image yielded an average of 1109 detected features, resulting in 48 matched image pairs with approximately 86 matched features per pair. In contrast, the corresponding amplitude images capture averaging 2,216 detected features and producing 56 matched pairs, each averaging 168 matched features. Here, we see the resulting number of average match features of the differential images is 163, which is close to the same for amplitude images. Figure 7 shows the stitching performance of the proposed method and the comparison with Stitching, Stitch2D and MIST. Here, Stitch2D could not produce any solution as it fails to align the images together. From Fig. 7a, we can see Stitching can only partially stitch images with a 10% overlap despite containing a seemingly sufficient number of matched features of the topographical images (see Table 1). This is due to the uneven distribution of matched features and the presence of feature-sparse images, which prevent the algorithm from directly stitching the topographical images. As a result, 15 out of 49 images are missing from the stitched image. MIST, on the other hand, performed better and could stitch all the topographical images with 10% overlap when the overlap percentage was manually specified as shown in Fig. 7b. However, like in previous analysis, the stitched topographical image introduced more noises such as misalignment (denoted by red solid box in Fig. 7d) and seam lines (denoted by yellow solid box in Fig. 7e), which degrades the stitched image to a unsuitable result. Again from Fig. 7c, we can clearly see our method outperformed the traditional approach where it can stitch all the topographical images with 10% overlap, without any sign of significant misalignment or generation of seam lines. To further investigate the regions where MIST fails, we can see our method provides correct alignment and smooth surfaces (denoted by dotted red and yellow boxes in Fig. 7d and e respectively) of the stitched topographical image.

Finally, Fig. 8 shows the comparison of the stitched topographical image via extracting features from amplitude and differential imaging channels. Similar to previous analysis, both stitched images are very similar, suggesting that our method can be generalized to other image types, serving as a valuable augmentation strategy for microscopy image stitching tasks.

Stitching of Pantoea sp. YR343 dataset 2 images using different second imaging channel. Here, (a) is the stitched amplitude channel image, (b) is the stitched differentiation image, (c) is the stitched topographical image with aid of amplitude image, (d) is the stitched topographical image with aid of the differentiation of topographical image along x axis.

Case study 3- implementation of high-resolution Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) images of lead titanate (PTO) thin film samples

To generalize the application of our proposed method, we further validated to the PFM dataset of PTO thin film samples and used phase-channel signals as the correlated second channel images. These measurements were performed using an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) in contact mode with PFM enabled to probe the local ferroelectric properties of the material. The images capture both amplitude and phase contrast, revealing domain structure and polarization orientation at the nanoscale. Each image was acquired at a resolution of 2048 × 2048 pixels, which provides excellent spatial detail across the scanned area. This resolution allows for flexible post-processing, including image split and stitching. For example, dividing the image into a 4 × 4 grid results in sixteen 512 × 512 sub-images, still large enough to preserve domain features and resolution for stitching algorithms testing. Thus, the dataset was obtained by splitting a 2048 × 2048 pixel topographical/phase image into sixteen 512 × 512 sub-images with a 10% overlap and slight rotation (1–3 degrees). Figure 9 shows the stitching performance of the proposed method, along with a comparison to MIST. Stitch2D and Stitching failed to produce any solutions, as they could not align the images properly (see Supplementary Appendix C). From Fig. 9a, we can see that the stitched image generated by MIST shows obvious seam lines, highlighting MIST’s limitations in handling rotations. In contrast, the proposed method successfully aligned the topographical images with the aid of phase-channel images.

Summary

In summary, we propose a microscopy imaging bi-channel aided stitching method to aim to gather larger volume of information needed to stitch multiple images via maximizing extraction of matching features. Here, the first imaging channel is the stack of images of interest to stitch together and the second channel is the stack of images, highly correlated to the first channel, where higher volume of detected and matched features between adjacent image pairs can be extracted. In other words, our proposed pipeline is designed to stitch any microscopy image of interest as follows- (1) performing feature detection and matching from the rich-featured correlated image channels (such as amplitude or differential images), (2) then using the feature information to optimize the camera pose estimation, and (3) then we apply the estimated transformations to warp the sparse-featured image of interest to stitch them together. We see that the existing stitching tools generally work well when the image of interest is either less complex such as environmental images or with significant overlapping (e.g. 30%) of image pairs. However, real microscopy experimental data is more complex with undistributed and sparse features and additional artifact noise. Furthermore, data acquisition with such an overlapping percentage can be extremely challenging in terms of experimental cost. We demonstrated our method to stitch two sets of complex biofilm assembly images with limited (e.g. 10%) overlaps where our method outperformed significantly than the traditional stitching tools like Stitching, Stitch2D and MIST. We believe that our method can be generalized to stitch any microscopy images (such as STM, STEM etc.) to study large-scale material structures and benefit the experimentalist to avoid erroneous analysis and discovery due to incorrect stitching. Although the amplitude channel is closely related to the differential of the topographic image, the amplitude images typically yield a higher number of detected features. For this reason, we prioritize the amplitude channel as the secondary input. However, in cases where amplitude or other auxiliary channels are unavailable, the differential image serves as a viable alternative to support the stitching process. In the future, we aim to automate the optimal selection of the second imaging channel by designing a hybrid objective metric of quantifying mean correlation between stacks of images from first and second imaging channel, and quantifying the mean detected and matched features (as per Table 1) of the candidate for second imaging channel. We aim to also integrate the method with this hybrid metric into microscopy for real-time automated stitching. Future work also seeks to extend the method towards (1) adapting deep-learning framework for improved detection of matched features and (2) adding workflow to gather prior knowledge of the features from pretraining with existing microscopy image data from correlated material systems. Also, we have assumed that the AFM image acquisition was conducted with optimal imaging condition, to minimize the random noises and artifacts of these experimental images, as in practice, the imaging parameters are carefully optimized prior to starting the grid acquisition. Once the optimal feedback parameters (e.g., gain values, scan rate, integral and derivative constants) are determined, the entire set of tiles is typically acquired under constant conditions to ensure stability and repeatability. Here, our approach tackles the limitation of SIFT algorithm to stitch optimally conditioned AFM-generated microscopy images with sparse features. Previous works also showcased the struggle of such feature based stitching algorithms to stitch microscopy images at non-optimal feedback parameters47,48. Therefore, in future, we aim to advance our framework with varying tuning parameters or non-optimal feedback parameters, where these experimental images will have random noises, along with sparse features. In other words, considering data acquisition under non-optimal parameters, it will be case for a separate image denoising problem, which is not in the scope for this manuscript. Thus, a denoising model can be further integrated into our proposed stitching method in future scope to increase robustness of our stitching algorithm under non-optimal imaging conditions.

Data availability

The analysis reported here along with the code is summarized in Notebook for the purpose of tutorial and application to other data and can be found in https://github.com/arpanbiswas52/Stitching_AFMimage.

References

Samsudin, S., Adwan, S., Arof, H., Mokhtar, N. & Ibrahim, F. Development of automated image Stitching system for radiographic images. J. Digit. Imaging. 26, 361–370 (2013).

Wang, Y. & Wang, M. Research on stitching technique of medical infrared images. in International Conference on Computer Application and System Modeling (ICCASM 2010) vol. 10 V10-490-V10-493 (2010). vol. 10 V10-490-V10-493 (2010). (2010).

Yang, F., He, Y., Deng, Z. S. & Yan, A. Improvement of automated image Stitching system for DR X-ray images. Comput. Biol. Med. 71, 108–114 (2016).

Zhao, X., Wang, H. & Wang, Y. Medical image seamlessly stitching by SIFT and GIST. in 2010 International Conference on E-Product E-Service and E-Entertainment 1–4 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEEE.2010.5661495

Song, S., Son, J. & Kim, M. H. Stitching of microscopic images for quantifying neuronal growth and spine plasticity. in Advances in Visual Computing (eds Bebis, G. et al.) 45–53 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17289-2_5. (2010).

Wei, Z., Dan, T., Ding, J., Dere, M. & Wu, G. A. General Stitching solution for Whole-Brain 3D nuclei instance segmentation from microscopy images. in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2023 (eds Greenspan, H. et al.) 46–55 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43901-8_5. (2023).

Lee, D. H., Lee, D. W. & Han, B. S. Possibility study of scale invariant feature transform (SIFT) algorithm application to spine magnetic resonance imaging. PLOS ONE. 11, e0153043 (2016).

Lin, B. et al. A registration algorithm for astronomical images based on geometric constraints and homography. Remote Sens. 15, 1921 (2023).

Qiu, S. et al. Star map Stitching algorithm based on visual principle. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 32, 1850028 (2018).

Eken, S. & Sayar, A. A MapReduce-based distributed and scalable framework for Stitching of satellite mosaic images. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 1863 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Stitching images of dual-cameras onboard satellite. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 128, 274–286 (2017).

Megha, V. & Rajkumar, K. K. Automatic Satellite Image Stitching Based on Speeded Up Robust Feature. in International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Vision (AIMV) 1–6 (2021). 1–6 (2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/AIMV53313.2021.9670954

Zarei, A. et al. MegaStitch: robust Large-Scale image Stitching. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–9 (2022).

Mohammadi, F. S., Mohammadi, S. E., Adi, M., Mirkarimi, P., Shabani, H. & S. M. A. & A comparative analysis of pairwise image Stitching techniques for microscopy images. Sci. Rep. 14, 9215 (2024).

Mohammadi, F. S., Shabani, H. & Zarei, M. Fast and robust feature-based Stitching algorithm for microscopic images. Sci. Rep. 14, 13304 (2024).

Fan, X. & Xia, S. Feature based automatic Stitching of microscopic images. in Advanced Intelligent Computing Theories and Applications. With Aspects of Contemporary Intelligent Computing Techniques (eds Huang, D. S., Heutte, L. & Loog, M.) 791–800 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74282-1_88. (2007).

Zhang, Y., Pang, B., Yu, Y. & Zhang, C. Automatic microscopy image stitching based on geometry features. in 2013 6th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing (CISP) vol. 2 927–931 (2013).

He, B. et al. vEMstitch: an algorithm for fully automatic image Stitching of volume electron microscopy. GigaScience 13, giae076 (2024).

Chalfoun, J. et al. Accurate and scalable microscopy image Stitching tool with stage modeling and error minimization. Sci. Rep. 7, 4988 (2017).

Brown, M. & Lowe, D. G. Automatic panoramic image Stitching using invariant features. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 74, 59–73 (2007).

Mansur, A. adamancer/stitch2d. (2024).

OpenStitching/stitching. OpenStitching. (2025).

Ma, B. et al. Use of autostitch for automatic Stitching of microscope images. Micron 38, 492–499 (2007).

Yang, F., Deng, Z. S. & Fan Q.-H. A method for fast automated microscope image Stitching. Micron 48, 17–25 (2013).

Bay, H., Ess, A., Tuytelaars, T. & Van Gool, L. Speeded-Up robust features (SURF). Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 110, 346–359 (2008).

Lowe, D. G. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. in Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision vol. 2 1150–1157 vol.2 (1999).

Lowe, D. G. Distinctive image features from Scale-Invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 60, 91–110 (2004).

Xu, C., Yan, J. & Yang, H. Image stitching method based on image edge detection and SIFT algorithm. in Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Electronic Information Technology and Computer Engineering 425–431Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1145/3501409.3501487

Gan, W., Wu, Z., Wang, M. & Cui, X. Image Stitching Based on Optimized SIFT Algorithm. in 5th International Conference on Intelligent Control, Measurement and Signal Processing (ICMSP) 1099–1102 (2023). 1099–1102 (2023). (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMSP58539.2023.10170989

Preibisch, S., Saalfeld, S. & Tomancak, P. Globally optimal Stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics 25, 1463–1465 (2009).

Sarlin, P. E., DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T., Rabinovich, A. & SuperGlue Learning Feature Matching With Graph Neural Networks. in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 4937–4946 (2020). 4937–4946 (2020). (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00499

Sun, J., Shen, Z., Wang, Y., Bao, H. & Zhou, X. L. F. T. R. Detector-Free Local Feature Matching with Transformers. in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 8918–8927 (2021). 8918–8927 (2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00881

Seo, J. H. et al. Automated Stitching of microscope images of fluorescence in cells with minimal overlap. Micron 126, 102718 (2019).

Millan-Solsona, R. et al. Analysis of biofilm assembly by large area automated AFM. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 11, 75 (2025).

Levin, A., Zomet, A., Peleg, S. & Weiss, Y. Seamless Image Stitching in the Gradient Domain. in Computer Vision - ECCV 2004 (eds. Pajdla, T. & Matas, J.) 377–389Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-24673-2_31

Binnig, G., Quate, C. F. & Gerber Ch. Atomic force microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 930–933 (1986).

Alonso, J. L. & Goldmann, W. H. Feeling the forces: atomic force microscopy in cell biology. Life Sci. 72, 2553–2560 (2003).

Botet-Carreras, A. et al. On the uptake of cationic liposomes by cells: from changes in elasticity to internalization. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 221, 112968 (2023).

Lidke, D. S. & Lidke, K. A. Advances in high-resolution imaging – techniques for three-dimensional imaging of cellular structures. J. Cell. Sci. 125, 2571–2580 (2012).

Müller, D. J. et al. Atomic force Microscopy-Based force spectroscopy and multiparametric imaging of biomolecular and cellular systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 11701–11725 (2021).

Kochan, K. et al. In vivo atomic force microscopy–infrared spectroscopy of bacteria. J. R Soc. Interface. 15, 20180115 (2018).

Checa, M. et al. Mapping the dielectric constant of a single bacterial cell at the nanoscale with scanning dielectric force volume microscopy. Nanoscale 11, 20809–20819 (2019).

Van Der Hofstadt, M. et al. Internal hydration properties of single bacterial endospores probed by electrostatic force microscopy. ACS Nano. 10, 11327–11336 (2016).

Lozano, H. et al. Electrical properties of outer membrane extensions from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Nanoscale 13, 18754–18762 (2021).

Millan-Solsona, R. Rmillansol/Large-Area-AFM-Analysis-and-Control. (2025).

Bible, A. N. et al. A Carotenoid-Deficient mutant in Pantoea sp. YR343, a bacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of Populus deltoides, is defective in root colonization. Front Microbiol 7, (2016).

Stanciu, S. G., Hristu, R., Boriga, R. & Stanciu, G. A. On the suitability of SIFT technique to deal with image modifications specific to confocal scanning laser microscopy. Microsc Microanal Off J. Microsc Soc. Am. Microbeam Anal. Soc. Microsc Soc. Can. 16, 515–530 (2010).

Stanciu, S. G., Hristu, R. & Stanciu, G. A. Influence of confocal scanning laser microscopy specific acquisition parameters on the detection and matching of Speeded-Up robust features. Ultramicroscopy 111, 364–374 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work (H.Z) was supported by the University of Tennessee startup funding of A.B. The authors acknowledge the use of facilities and instrumentation at the UT Knoxville Institute for Advanced Materials and Manufacturing (IAMM) and the Shull Wollan Center (SWC) supported in part by the National Science Foundation Materials Research Science and Engineering Center program through the UT Knoxville Center for Advanced Materials and Manufacturing (DMR-2309083). Work by R.M, S.R.B., M.C, L.C and J.L.M was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science FWP ERKCZ64, Structure Guided Design of Materials to Optimize the Abiotic-Biotic Material Interface, as part of the Bio preparedness Research Virtual Environment (BRaVE) initiative. AFM measurements and sample preparation were conducted as part of a user project at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (CNMS), which is a US Department of Energy, Office of Science User Facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The authors would like to sincerely thank Scott Retterer for his generous assistance in the acquisition of funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.B supervised the project, supported funding for H.Z, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. H.Z designed the stitching algorithm, wrote the codes for implementation and analysis, analyzed data, prepared figures and co-wrote the paper. R.M wrote codes for image flattening, conducted AFM experiments to generate data, assisted with analysis and paper writing. M.C and L.C assisted with the data preparation and analysis of the results. S.R.B and J.L.M grew the samples used. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, H., Millan-Solsona, R., Checa, M. et al. A bi-channel aided stitching of atomic force microscopy images. Sci Rep 15, 41897 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25855-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25855-y