Abstract

High-quality distribution data are essential for conservation planning but, are often scarce for mountain ecosystems. We integrated six decades of published and unpublished distribution records of herpetofauna from a mountain national park in Romania, and assessed the spatiotemporal patterns in species occurrences and consequent challenges for conservation. The number of records significantly differed from the expected values, based on the proportion of the area of altitudinal domains. We documented species richness, ranges and habitat changes across the park. Richness was lower in peripheral regions, with stable or expanding populations concentrated in the integral protection zone and the northwestern part of the buffer zone. Declines of introduced trout from alpine lakes facilitated recolonization by amphibians, while man-made structures, the spread of other species (e.g. Bufo bufo, Podarcis muralis, Zootoca vivipara). We emphasize the need for robust monitoring programs for herpetofauna in mountain habitats, to reduce biases and accurately assess, understand, and predict the dynamics of species distributions. While the park is still well-preserved, the creation and restoration of aquatic habitats are recommended to support amphibian populations. Targeted conservation measures are vital to mitigate the impact of man-made structures and tourism in the more accessible areas that overlap amphibian and reptile hotspots.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The present loss of biodiversity worldwide is occurring at an unprecedented rate since the onset of the Anthropocene1. Given that biodiversity is not evenly distributed across the world2, conservation efforts must be directed towards the most threatened taxa and impacted regions. Moreover, species’ responses to various threats differ due to variation in their biological traits, making some species more vulnerable than others3. To prioritize, develop effective conservation strategies, and mitigate the negative impacts of biodiversity loss, a critical step is mapping species distributions. This allows to document range shifts, contractions, or expansions, and to identify both the most affected regions and the most threatened species. Consequently, significant resources and efforts are being directed towards mapping species distributions at global (e.g. the Global Biodiversity Information Facility), regional, national, and local levels. However, robust species distribution assessments require high-quality datasets, which are generally considered the foundation that drives the success of conservation planning policies4. Yet, present-day databases still face data-related challenges5. Data quality and proper management are often lacking, with more emphasis placed on quantity rather than quality6,7.

Mountain ecosystems are an essential component of the global life-support system. They encompass more than 30% of all land and host approximately 85% of amphibian, bird, and mammal species8. Mountain ecosystems concentrate more than 90% of species richness hotspots and about 40% of endemism hotspots worldwide due to their topographic complexity9. Meanwhile, these ecosystems are highly vulnerable to major anthropogenic threats, especially climate change and its derived effects, such as increased UV radiation, altered hydrological cycles, and shifting temperature patterns10. Many species in mountain areas are at the upper limit of their altitudinal ranges, making them particularly susceptible to environmental changes. There is a general trend of local species decline with increasing altitude11, and elevation is a significant predictor of species extinction risk12. Given that montane regions are projected to warm three times faster than the global average13, species are expected to show phenological changes, such as earlier seasonal activities14, and to shift their ranges towards higher elevations. Together, these processes increase the risks of local extinctions and leave mountain ecosystems more vulnerable than their lowland counterparts.

Amphibians and reptiles are the most threatened terrestrial vertebrates worldwide15,16. Population declines are caused by multiple threats, including habitat destruction, climate change, pathogens, and the introduction of alien species. In Europe, nearly one-third of amphibians and 12% of reptiles are considered threatened17,18. The earliest initiatives to map the distribution of amphibians and reptiles at the European level were conducted at a coarse, 50-sq km grid cell resolution19,20, while the latest21 are progressing towards a finer, 10-sq km grid cell resolution. Although several European countries maintain detailed atlases or online databases22, there is a gradient of declining data density from west to east across Europe. In Romania, the latest nationwide distribution of amphibians and reptiles was mapped at a 5-sq km grid resolution23,24; still, this spatial scale is too coarse to detect changes in range within relatively small protected areas, especially in mountain regions. Apart from spatial resolution, temporal data (i.e. time-series) are equally important, as they allow detecting shifts in species ranges and population declines over time25,26. In turn, changes in species occurrences are useful for assessing the risk of extinction27. Identifying temporal trends requires long-term and standardized occurrence datasets, which are not always available. Thus, historical data provide valuable information about past species distributions28.

Retezat National Park (RNP), established in 1935, is Romania’s oldest national park and one of the most ecologically significant protected areas in the Carpathians. Given its long history of protection and relatively pristine status, it serves as an ideal natural laboratory for analyzing changes in species distribution over time. A recent study29 assessing the completeness of faunistic inventories over the past 70 years in RNP revealed significant biases that affect management and conservation efforts. Long-term monitoring is widely acknowledged as an essential tool for biodiversity management and conservation30. Monitoring programs can provide appropriate data to document the distribution of species across space and time31,32. Over the past decades, monitoring and management at the landscape scale have justifiably attracted increased attention. However, such approaches are not always sufficient for understanding and managing biodiversity loss. Top-down global monitoring programs designed to support local or regional management objectives, such as those targeting mountain ranges and threatened taxa, are important, and global-scale biodiversity monitoring will have to make use of these data. Long-term and fine-scale monitoring of amphibians and reptiles remains limited in mountain areas due to difficult access.

To address this gap, we compiled a fine-scale (i.e. 1-sq-km resolution) database of amphibian and reptile species occurrence records from RNP, based on published records, online repositories, and over four decades of fine-scale monitoring and surveys. In addition, we conducted a small-scale aquatic habitat monitoring program for amphibians in a selected area of RNP, using a standardized protocol that recorded presence/absence data over time. However, the continuity of this study was limited due to inconsistent funding. While we acknowledge the limitations associated with published data records and those from online repositories, as well as inconsistencies in monitoring, our study addresses the pressing gap in long-term, high-resolution data on species distributions in mountain ecosystems. Such temporal depth, combined with high spatial resolution, is rarely achieved in mountain biodiversity research and significantly enhances our ability to formulate hypotheses about the processes driving species range shifts.

We aimed to explore the spatial and temporal patterns of species occurrences and the potential drivers of change, to identify challenges in conservation planning in mountain ecosystems. Specifically, we assessed the dynamics of (1) biases in species surveys, (2) species richness, and (3) species ranges, using occurrence data accumulated across six decades of research in RNP. Lastly, (4) we assessed small-scale changes in habitat use by amphibians, using data obtained from repeated, standardized surveys. We expected to observe both spatial and temporal biases affecting distribution patterns (e.g. due to uneven spatial density of observers), and a temporal increase in the number of occurrence records over time (e.g. due to advances in and increased availability of technology for recording and submitting species observations). We hypothesized that patterns of species richness, ranges and habitat use have shifted over time and space, due to changes in habitat availability, such as the drying of temporary aquatic habitats and the expansion of forest habitats and dwarf pine shrubbery at the expense of alpine meadows, as well as shifts in aquatic habitat quality due to the introduction of alien fish species and increase in the frequency of droughts. Such changes are expected to influence species richness hotspots and coldspots.

Results

The database used for the analysis included 1,824 unique occurrence records (raw dataset available as Supplementary Data S1) of 17 species (9 amphibians and 8 reptiles) recorded between 1960 and 2024, in RNP (Table 1; Fig. 1). Amphibians accounted for 78% of the total records, while reptiles 22%. Rana temporaria (the common frog) had the highest number of occurrences (43% of all records, and 55% of all amphibian records), followed by Mesotriton alpestris (the alpine newt) and Zootoca vivipara (the viviparous lizard). Eight species (i.e. 47%) had fewer than ten occurrence records, while three of them (i.e. Lissotriton vulgaris, Pelophylax ridibundus, and P. kl. esculentus) were recorded only once (Table 1).

Spatial distribution of herpetofauna in Retezat National Park, Romania. The figure shows point data (i.e. field, unpublished data, and published records) of amphibian and reptile occurrences obtained between 1960 and 2024, plotted over a 1-sq km cell grid encompassing the study area. Maps were created in ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.5.2 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Altitudinal ranges varied greatly among species, with some species found along a narrow altitudinal range (e.g. Lacerta agilis, observed between 726 and 847 m) while others occupied a broader range (Table 1; Fig. 2). The viviparous lizard (Zootoca vivipara) occurs at the highest altitude (2,461 m) and has the broadest altitudinal range, as its distribution is not restricted by humidity or the presence of water bodies. The observed number of occurrence records differed significantly from the expected number, based on the proportion of the area of each altitudinal domain (chi-squared test, χ2 = 60.272, df = 8, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Altitudinal ranges and gaps in the distribution data of amphibians and reptiles from Retezat National Park, Romania. The upper panels show the altitudinal distribution of the most abundant amphibian (left) and reptile (right) species, based on the occurrence records obtained between 1960 and 2024. The bottom panels show the significant differences between observed (black bars) and expected (grey bars) number of occurrence records (for all species), based on the area of each altitudinal domain (see also Supplementary Table S2).

Temporal and spatial biases

The chi-squared and the Welch two-sample t-test indicated significant temporal (χ2 = 8,356.5, df = 28, P < 0.001) and spatial biases (t = -34.542, df = 2,691.9, P < 0.001) in the data. The temporal analysis revealed that the number of occurrence records was very low in the 1960s and increased rapidly after 2000 (Fig. 3).

The number of occurrence records and species richness varied across the three time periods and the entire 64-year span (Fig. 4). During the 1960–2000 period, the highest number of occurrence records and species richness were found in the south-eastern part of the park, particularly along the national road DN 66A. Between 2001 and 2011, the number of occurrence records and species richness peaked in the north-western region, near the research infrastructure at Gura Zlata, and extended further into the central strictly protected area, particularly around Gemenele and Bucura Lakes. Between 2012 and 2024, the highest values were again recorded in the core strictly protected area and near the Gura Apelor dam. Over the entire study period, the highest number of occurrence records and species richness were observed along the park’s north-western border (near Gura Zlata) and in the south-eastern region (Câmpușel area), which is more accessible and frequently visited by tourists. In contrast, the most forested areas in the north-east and south-west of the park had few occurrence records. The spatial bias is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Temporal variation in amphibian and reptile species richness in Retezat National Park, Romania. The figure shows the variation in the number of occurrence records and species richness across three time periods (decades 1960–2000, 2001–2011, and 2012–2024) and over the entire 64-years period (1960–2024), at a resolution of 1-sq km grid cells.

Spatial bias in the inventory of amphibians and reptiles from Retezat National Park, Romania. The spatial bias is shown for all data collected between 1960 and 2024, as follows: (A) location of centralized records in 1-sq km cells; (B) species richness per 1-sq km grid cells; (C) hotspots of occurrence records, calculated as point densities (radius 3,000 m). The map was created in ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.4 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Changes in species richness and range shifts

Species richness differed between 1960 and 2011 and 2012–2024, ranging from − 12 to + 8 species (Fig. 6). We identified hotspots of decline in the peripheral part of the park, while stable and expanding amphibian and reptile populations were concentrated in the integral protection zone, including Gemenele Scientific Reserve, and in the north-western part of the buffer zone, near the Gura Apelor dam.

Shifts in species ranges between 1960 and 2011 and 2012–2024 are documented only for species with sufficient records (i.e. three amphibian and four reptile species; Fig. 7). In amphibians and the lizard Podarcis muralis, increasing trends were concentrated in the north-western part of the buffer zone, near the Gura Apelor dam. For both amphibians and reptiles, stable ranges were concentrated in the core area of the integral protection zone, except for Bombina variegata, Anguis colchica, and P. muralis.

Range shifts in amphibians and reptiles. The figure shows the changes in the ranges of seven of the most abundant amphibian and reptile species, between 1960–2011 and 2012–2024, in Retezat National Park, Romania. The 1-sq km cells represent: white = absence, red = recorded only during 1960–2011, purple = recorded only during 2012–2024, and orange = recorded during both periods (i.e. 1960–2024).

Habitat use by amphibians

Three amphibian species, R. temporaria, B. bufo, and M. alpestris, are abundant at high altitudes. Their range expansion towards higher altitudes is limited only by the availability of suitable aquatic habitats. The small-scale study regarding habitat use by amphibians in the Judele Valley included 28 permanent and temporary aquatic habitats that were surveyed in the past (2004–2006). During the recent surveys (i.e. 2023–2024), we found that three of them (11.8%) had completely dried up. The three amphibian species present in the area showed significant changes in their use of aquatic habitats. While the common frog (Rana temporaria) was the most abundant species during 2005–2006 surveys, it showed a significant decline over time. In contrast, the common toad (Bufo bufo), initially recorded from only two aquatic habitats, significantly expanded its habitat use to 12 aquatic habitats. The alpine newt (Mesotriton alpestris) also expanded its habitat use, though to a more moderate extent (Table 2, Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

Gaps and biases in amphibian and reptile distribution

Our study is among the few in the region to use long-term occurrence data to evaluate changes in species distribution in a mountain protected area. We addressed regional gaps, as Central and Eastern Europe is underrepresented in global assessments. We linked habitat change with conservation planning, highlighting alpine meadows and alpine water bodies as priority habitats.

The distribution of amphibians and reptiles in RNP has been relatively well studied over the past six decades. However, our analysis revealed data gaps and biases that hinder the reliability of spatial mapping and conservation planning. This result is consistent with a previous study analyzing the biases in faunistic surveys in RNP29. Thus, most occurrence records were clustered around the park’s research facilities (i.e. the two research stations at Gura Zlata and Gemenele) and available infrastructure (e.g. roads, camping sites). Of the 17 species reported from the park, eight had fewer than ten occurrence records. In addition, the crested newt (Triturus cristatus) was observed only in the vicinity of the park. Furthermore, a high-altitude record of the green toad (B. viridis) from Fața Retezatului33, based on a single juvenile specimen caught in a pitfall trap, is questionable. Given the presence of a large population of common toad (B. bufo) in the area near Lake Gemenele, we consider this record to be a probable misidentification of a poorly preserved specimen. Nevertheless, despite extensive studies in the Gemenele area, the occurrence of B. bufo was not reported in publications from the 1970s and 1980s. An extensive limnological study34 of Lake Gemenele and the surrounding wetlands documented the presence of common frogs, but not common toads. The first records of B. bufo in alpine lakes, including Lake Gemenele, date from 2000. It remains unclear whether the species was previously overlooked due to small population sizes or the demise of introduced trout allowed it to (re)colonize the newly available aquatic habitats. Notably, common toads successfully breed in several lakes that still support large fish populations (e.g. Gemenele, Zănoaga, Negru lakes).

The presence of water frogs (P. ridibundus) was only detected in 2024 in a single, isolated lake (Tăul fără fund), despite repeated surveys in the area since 198529. Similarly, the grass snake (N. natrix) was observed for the first time in the same lake in 2022. The recent increase in the number of occurrence records for the wall lizard (Podarcis muralis) is limited to the vicinity of roadside habitats, suggesting that road construction facilitated its spread.

The difference between the expected and reported number of occurrence records across altitudinal domains (Fig. 2) can be attributed to the steep slopes of the mountain range and the lack of lentic aquatic habitats between the valleys and the tree line. The permanent water bodies are located between 1,690 and 2,260 m, with an average altitude of 2,045 m35. Accessibility also poses a significant challenge, as few trails cross forested areas, while alpine pastures interspersed with dwarf pines are more accessible to researchers.

Changes in species richness, ranges and habitat use

Significant changes occurred during the last century in habitat quality in the alpine area, affecting both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Extensive forest fires have destroyed large areas of dwarf pine (Pinus mugo) and Swiss pine (P. cembra)36. Aquatic ecosystems were affected by the introduction of fish species during the mid-20th century. Alien trout species (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Salvelinus fontinalis, Coregonus peled and C. lavaretus) and native trout (Salmo trutta) were introduced into 20 permanent lakes for angling purposes37. Most introduced fish did not establish self-sustaining populations, and today only a few native and introduced trout populations persist in these alpine lakes. In contrast, fish introduced accidentally later as bait, such as the common minnow (Phoxinus phoxinus), are currently abundant in many formerly stocked lakes (pers. obs.). The alpine newt (M. alpestris) has benefited from the decline of introduced fish populations and expanded its distribution to higher altitudes. The small-scale study conducted in the Judele Valley highlighted important changes in aquatic habitat use by amphibians. It revealed a decline in habitat occupancy of the previously abundant R. temporaria and an expansion of the once rarer B. bufo. The decline in the number of available temporary aquatic habitats that dried up cannot, by itself, explain these changes. A contributing factor could be the spread of the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), a topic under investigation in amphibian populations within RNP.

The average annual temperature increased by 1.5 °C between 1960 and 2019 in RNP, speeding the expansion of forest habitats and dwarf pine shrubbery towards higher altitudes, at the expense of alpine meadows38. This is consistent with the overall pattern observed in alpine areas worldwide39. A 15-years long study on three amphibian species (B. bufo, T. carnifex, and R. temporaria) in the Alps highlighted the ability of amphibians to achieve rapid elevational shifts in response to climate warming40. Similarly, a study from the Iberian Peninsula showed that while most species barely shifted their ranges northwards (except for Alytes dickhilleni), they predominantly expanded their elevational limits in mountain areas41. This response enables species to remain within their climatic envelope across relatively short distances in mountainous areas and may explain, at least in part, the changes documented by our study in RNP.

Conclusions for conservation planning

There is no single, general explanation for the geographic distribution limits of species. However, maintaining aquatic habitats suitable for reproduction in the alpine area is vital for the long-term survival of amphibians. While little can be done to mitigate drought, preventing the introduction of fish species in high-altitude water bodies is a major requisite, given the well-documented negative impact of fish introductions on amphibians42,43. Creating and restoring aquatic habitats in the mountains has proved to be an efficient solution for supporting amphibian populations44. Thanks to the Conservation Evidence initiative45 (https://www.conservationevidence.com/), a wealth of information on good management practices for amphibians and reptiles is now available. Maintaining amphibian populations that breed in permanent water bodies should be considered a priority, since they often act as source populations, further spreading and colonizing nearby temporary habitats.

The decline in meadow cover, due to tree and shrub encroachment, coupled with a decline in the intensity and extent of seasonal mountain grazing, requires active management measures to maintain a mosaic of habitats favorable for alpine reptiles.

Despite the significant spatial and temporal biases in the available distribution data, our study highlights significant range shifts of amphibian and reptile species in a relatively well-managed and well-preserved protected area. Coping with the relatively rapid responses of these species to environmental change requires more focused monitoring programs. Our study provides a sound baseline for a long-term monitoring program.

While we discuss potential drivers of species range shifts, these factors were not explicitly modelled or quantitatively analyzed in this study. This was mainly due to the lack of high-resolution climate and land-cover products covering the full-time span of our study. Confirming the true absence of a species is difficult, as present species may go undetected. To overcome such challenges, future research should focus on narrower temporal windows within our dataset. Such studies could integrate ecological modeling approaches to simultaneously estimate occurrence, abundance, and detection probability, as these methods are essential for understanding the mechanisms underlying the observed patterns.

Materials and methods

Study area

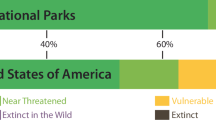

Retezat National Park is located in the Southern Carpathians of Romania (Fig. 8), covering a total area of 38,047 ha, of which 4,350 ha are designated as a strictly protected area46. Since 2007, RNP overlaps with two Natura 2000 sites: ROSCI0217 (Retezat) and ROSPA0084 (Retezat Mountains). The former covers a larger area (43,528 ha), which includes the park and extends further south-west, while the latter overlaps with the park’s boundaries. A more detailed description of RNP is provided by Cogălniceanu et al.29 and by the RNP Administration (https://retezat.ro/). When compared to the nearby mountain ranges in the Southern Carpathians, the Retezat Mountains differ in altitudinal distribution, with 40% of its area above 1,600 m47, whereas the average for the Southern Carpathians is 25% (Fig. 9).

The study area. The figure shows Retezat National Park (red outline) and the extended Natura 2000 area (green outline). The limits of the Gemenele Scientific Reserve are shown as a red, dashed outline, while the Judele Valley, where the small-scale, intensive amphibian surveys were conducted in 2005–2006 and 2023–2024, is represented by a black outline. The inset shows the location of the study area in Europe and Romania. The map was created in ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.4 software (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Altitudinal variation in Retezat National Park, Romania. The figure shows the percentage of area across altitude intervals in RNP, based on data from47.

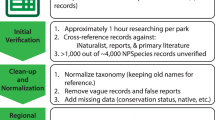

Data sources and field surveys

Our own field data were collected as part of multiple research projects carried out in RNP between 2000 and 2024. The presence of amphibians was documented through direct observations in terrestrial habitats, dip-netting surveys, and visual identification of spawn and/or tadpoles in aquatic habitats. The presence of reptiles was documented visually along transects and through active searches in terrestrial habitats. For both amphibians and reptiles, additional occurrence records were obtained from accidental captures in pitfall traps set up for invertebrate surveys.

We also conducted a small-scale study to assess shifts in the habitat use by three amphibian species within a 380-ha area in the Judele glacial valley48. This area is delineated by the lakes Zănoaga (2,000 m), Judele (2,145 m), Ascuns (2,180 m) and Răsucit (2,100 m) (Fig. 9). We used a standardized survey protocol covering 40 water bodies, both permanent and temporary. The surveys were repeated during 2005–2006 and 2023–2024 by the same experienced observers, which increased species detectability and ensured that absence records were reliable. The protocol involved daytime visual transects, searching for larvae or freshly metamorphosed individuals in aquatic habitats, and for adults and subadults in the surrounding terrestrial habitats, and along the shoreline. Larval stages were detected through visual inspections or dip-net sampling. Of the 40 surveyed water bodies, 65% (n = 26) were permanent oligotrophic glacial lakes, with depths ranging from 0.1 to 29 m, typically surrounded by grasslands, scree, or alpine shrub vegetation. The remaining 35% (n = 14) were temporary water bodies. All water bodies were located within an altitudinal range of 1,920 to 2,260 m. Approximately one-fifth of the surveyed water bodies had a pH below 5. Fish were present in only one lake, while invertebrate predators were detected in 42.5% of the water bodies (n = 17). The mean distance between the three nearest neighboring water bodies was 198.8 ± 97 m. During the 2023–2024 inventory, we re-surveyed 28 water bodies.

Data provided by the park administration in project reports were based on a series of biodiversity inventories conducted between 2019 and 2020 to support the park’s management plan. Occurrence records from scientific publications prior to 2000 were obtained from the review compiled by Cogălniceanu et al.49, while those published up to 2012 were compiled from other relevant sources23,24,48,50. The review by Cogălniceanu et al.49 included only unique records per location.

Occurrence records from publicly available databases were retrieved from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility51 (https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.u8tqq8) using the spatial filtering option to include only the records within the study area (i.e. a polygon overlapping the limits of RNP). Given the potential issues associated with GBIF data, particularly positional uncertainty in iNaturalist records, which is known to affect spatial analyses for range-restricted or threatened species in mountainous environments52, we applied a rigorous data-cleaning process53 to minimize such uncertainty and ensure reliability. Specifically, we removed records with (i) coordinate uncertainty > 100 m, (ii) missing or zero coordinates, (iii) duplicated observations, (iv) coordinates lacking decimal precision, (v) observations falling outside the study area, (vi) doubtful observations (i.e. species outside their known ranges or individuals considered vagrants54, or (vii) mismatched latitude/longitude values. We also thoroughly validated taxonomic information by removing synonyms or misspelt species names, and by correcting taxonomic inconsistencies. The taxonomy used in this study follows Speybroeck et al.55, with the modification proposed by Mutz and Böhme56.

Data integration and spatial aggregation

We integrated the data from all sources (our own fieldwork, project reports, scientific publications, and publicly available databases) to obtain a comprehensive database of amphibian and reptile occurrence records within RNP (Supplementary Data S1). We used ESRI ArcGIS Pro (versions 3.4 and 3.5.2)57 for data management and for creating the maps shown in Figs. 1 and 5, and 8. All species occurrence datasets were post-processed and spatially aggregated in an ESRI file geodatabase containing the following data fields: (1) scientific name, (2) locality, (3) year, (4) coordinates source, (5) decimal latitude, (6) decimal longitude, (7) coordinate uncertainty (m), (8) elevation (m), (9) data source, (10) relief unit, and (11) ETRS 1-sq km grid cell.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses and resulting figures were done in R v. 4.4.358. We analyzed the spatial data using 1-sq km grid cells as a method of data thinning, instead of using georeferenced point data which were often clustered. To assess whether the observed number of occurrence records differed significantly from the expected number based on the proportion of area of each altitudinal domain, we performed a Chi-squared test. We tested for spatial and temporal biases using the “spatiotemp_bias” function in the “dynamicSDM” R package59. Specifically, we applied the Chi-squared test to assess temporal bias and the Welch two-sample t-test for spatial bias.

To identify hotspots of species occurrences and richness, we divided RNP into 458 1-sq km grid cells and mapped the occurrences (number of records) for each species, as well as species richness, measured as the number of species within each cell.

To detect changes in amphibian and reptile distribution, we mapped the species richness and the presence or absence of species across three different periods: 1960–2000, 2001–2011, and 2012–2024. Due to the lower number of occurrences collected during the periods 1960–2000 and 2001–2011, we merged these periods to estimate the change in species richness between 1960 and 2011 and 2012–2024. Species range shifts between 1960 and 2011 and 2012–2024 were assessed by determining whether species ranges contracted, expanded, or remained stable over time, based on the grid cells that were colonized (i.e. had no occurrence record during the first period and at least one during the second period) or decolonized (i.e. had at least one record during the first period but none during the second). Since the distribution data were binary, containing 0 (absence) and 1 (presence), we reclassified the occurrences from the 2012–2024 period as 2, in order to visualize where ranges remained stable. This allowed us to sum the maps and generate distinct occurrence categories: absence (0), decolonization (1), colonization (2), and stability (3).

We acknowledge the inherent detectability limitations of presence-absence surveys, particularly those influenced by observer bias, weather conditions, and the degree of standardization in survey protocols. These limitations were taken into account when interpreting the results. Confirming true species absence is difficult, as species that are present may go undetected. Thus, we relied on “pseudo-absences”. For example, the absence of amphibians was associated with aquatic habitats that were dry or with remote water bodies that have not yet been colonized.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are available as Supplementary Information files S1–S3.

References

Johnson, C. N. et al. M. Biodiversity losses and conservation responses in the anthropocene. Science 356, 270–275 (2017).

Dobson, A. P. & Harte, J. Latitudinal gradients in biodiversity: Understanding the mechanisms behind the tropics’ richness. Ecol. Lett. 26, 456–468 (2023).

Isaac, N. J. & Cowlishaw, G. How species respond to multiple extinction threats. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 271, 1135–1141 (2004).

Stephenson, P. J. et al. Measuring the impact of conservation: the growing importance of monitoring fauna, flora and Funga. Diversity 14, 824. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14100824 (2022).

Elliott, M. J., Poelen, J. H. & Fortes, J. A. Toward reliable biodiversity dataset references. Ecol. Inf. 59, 101132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2020.10113 (2020).

Michener, W. K. & Brunt, J. W. Ecological Data: Design, Management and Processing (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000).

Sutter, R. D., Wainscott, S. B., Boetsch, J. R., Palmer, C. J. & Rugg, D. J. Practical guidance for integrating data management into long-term ecological monitoring projects. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 39, 451–463 (2015).

Zhang, L. & Wang, J. Mountain biodiversity, species distribution and ecosystem functioning in a changing world. Diversity 15, 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15070799 (2023).

Fan, Y. Z. et al. Resurvey after 20 years: updating the distribution, population, and potential threats of the Chinting alpine Toad. Asian Herpetological Res. 15, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.3724/ahr.2095-0357.2023.0043 (2024).

Schmeller, D. S. et al. Scientists’ warning of threats to mountains. Sci. Total Environ. 853, 158611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158611 (2022).

Peters, M. K. et al. Predictors of elevational biodiversity gradients change from single taxa to the multi-taxa community level. Nat. Commun. 7, 13736. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13736 (2016).

Guirguis, J., Goodyear, L. E., Finn, C., Johnson, J. V. & Pincheira-Donoso, D. Risk of extinction increases towards higher elevations across the world’s amphibians. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 1952–1963 (2023).

Nogués-Bravo, D., Araújo, M. B. & Errea, M. P. Martínez-Rica, J. P. Exposure of global mountain systems to climate change. Global Environ. Change. 17, 420–428 (2007).

Vitasse, Y. et al. Phenological and elevational shifts of plants, animals and fungi under climate change in the European alps. Biol. Rev. 96, 1816–1835 (2021).

Cox, N. et al. A global reptile assessment highlights shared conservation needs of tetrapods. Nature 605, 285–290 (2022).

Luedtke, J. A. et al. Ongoing declines for the world’s amphibians in the face of emerging threats. Nature 622, 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06578-4 (2023).

Crnobrnja-Isailović, J. et al. European Red List of Amphibians. Measuring the pulse of European biodiversity using the European Red List (European Commission, in press).

Bowles, P. et al. European Red List of Reptiles. Measuring the pulse of European biodiversity (European Commission, in press).

Gasc, J. P. et al. Atlas of amphibians and reptiles in Europe (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, (1997).

Sillero, N. et al. Updated distribution and biogeography of amphibians and reptiles of Europe. Amphibia-Reptilia 35, 1–31 (2014).

Băncilă, R. I., Lattuada, M. & Sillero, N. Distribution of amphibians and reptiles in agricultural landscape across Europe. Landscape Ecol. 38, 861–874 (2023).

Sillero, N., Oliveira, M. A., Sousa, P. & Sousa, F. Gonçalves-Seco, L. Distributed database system of the new atlas of amphibians and reptiles in europe: the NA2RE project. Amphibia-Reptilia 35, 33–39 (2014).

Cogălniceanu, D. et al. Diversity and distribution of amphibians in Romania. ZooKeys 296, 35–57. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.296.4872 (2013).

Cogălniceanu, D. et al. Diversity and distribution of reptiles in Romania. ZooKeys 341, 49–76 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.341.5502

Denoël, M. Newt decline in Western europe: highlights from relative distribution changes within guilds. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 2887–2898 (2012).

Arntzen, J. W. Patch analysis of atlas data reveals pattern and process of species replacement. Frontiers of Biogeography 15, e59627 (2023). https://doi.org/10.21425/F5FBG59627

Cordillot, F. & Klaus, G. Threatened Species in Switzerland. Red List Synthesis Report, Status 2010 (Federal Office for the Environment, 2011).

Ficetola, G. F. et al. Integrating historical and recent data to measure long-term trends of endangered subterranean species. Biol. Conserv. 296, 110695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2024.110695 (2024).

Cogălniceanu, D. et al. Awaiting discovery: how biases in faunistic surveys hinder conservation in mountain protected areas. A case study from romania’s oldest National park. PLOS One. 20, e0319871. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0319871 (2025).

Gitzen, R. A. et al. Design and Analysis of Long-Term Ecological Monitoring Studies (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Braunisch, V. & Suchant, R. Predicting species distributions based on incomplete survey data: the trade-off between precision and scale. Ecography 33, 826–840 (2010).

Kéry, M. et al. Analysing and mapping species range dynamics using occupancy models. J. Biogeogr. 40, 1463–1474 (2013).

Fuhn, I. Cercetări sinecologice cantitative Asupra epigaionului Feței retezatului. Sargetia 10, 137–155 (1974).

Godeanu, S. Contribuții La cunoașterea sinecologică a Zoocenozelor tinovului Gemenele Din parcul Național Retezat. Sargetia 10, 155–176 (1974).

Pișotă, I. Lacurile Glaciare Din Carpații Meridionali (Studiu hidrologic (Editura Academiei, 1974).

Feurdean, A. et al. Fire has been an important driver of forest dynamics in the Carpathian mountains during the holocene. For. Ecol. Manag. 389, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.11.046 (2017).

Decei, P. Lacuri De munte. Drumeție și Pescuit (Editura Sport-Turism, 1981).

Romanian Ministry of Environment, Water and Forests. Order 2.095/2024 on the approval of the Management Plan of the Retezat National Park, including the reserves 2.494 Gemenele, 2.496 Peștera Zeicului, together with partially overlapping Natura 2000 sites - ROSCI0217 Retezat and ROSPA0048 Munții Retezat. Official Monitor of Romania 1018 bis. (2024). Available from: https://monitoruloficial.ro/e-monitor/

Lu, X. et al. Patterns, dynamics and drivers of alpine treelines and shrublines. Nat. Reviews Earth Environ. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-025-00703-9 (2025).

Tiberti, R., Mangiacotti, M. & Bennati, R. The upward elevational shifts of pond breeding amphibians following climate warming. Biol. Conserv. 253, 108911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108911 (2021).

Enriquez-Urzelai, U., Bernardo, N., Moreno-Rueda, G., Montori, A. & Llorente, G. Are amphibians tracking their Climatic niches in response to climate warming? A test with Iberian amphibians. Clim. Change. 154, 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02422-9 (2019).

Hecnar, S. J. & M’Closkey, R. T. The effects of predatory fish on amphibian species richness and distribution. Biol. Conserv. 79, 123–131 (1997).

Hartel, T. et al. The effect of fish and aquatic habitat complexity on amphibians. Hydrobiologia 583, 173–182 (2007).

Smith, R. K., Meredith, H. & Sutherland, W. J. in Amphibian Conservation in What Works in Conservation. 9–64 (eds Sutherland, W. J., Dicks, L. V., Petrovan, S. O. & Smith, R. K.) (Open Book, 2020).

Sutherland, W. J., Dicks, L. V., Petrovan, S. O. & Smith, R. K. What Works in Conservation (Open Book, 2021). https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0267

Coldea, G. & Cristea, V. The Vascular Plant Communities of the Retezat National Park (Southern Carpathians) (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Urdea, P. Munții Retezat. Studiu Geomorfologic (Editura Academiei Române, 2000).

Cogălniceanu, D., Băncilă, R., Plăiaşu, R., Samoilă, C. & Hartel, T. Aquatic habitat used by amphibians with specific reference to Rana temporaria at high elevations (Retezat mountains National Park, Romania). Ann. De limnologie - Int. J. Limnol. 48, 355–362 (2012).

Cogălniceanu, D., Ghira, I. & Ardeleanu, A. Spatial distribution of herpetofauna in the Retezat mountains National Park - Romania. Biota 2, 9–16 (2001).

Plăiaşu, R., Băncilă, R. I., Samoilă, C. & Cogălniceanu, D. Factors influencing the breeding habitat use by amphibians in the alpine area of the Retezat National park (Romania). Travaux Du Muséum Natl. D’Histoire Naturelle Grigore Antipa. 53, 469–478 (2010).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility. GBIF Occurrence Download. Accessed on: 30 September 2024. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.u8tqq8

Contreras-Díaz, R. G. et al. Well-intentioned initiatives hinder Understanding biodiversity conservation: cloaked iNaturalist information for threatened species. Biol. Conserv. 282, 110042 (2023).

Cobos, M. E., Jiménez, L., Nuñez-Penichet, C., Romero-Alvarez, D. & Simoes, M. Sample data and training modules for cleaning biodiversity information. Biodivers. Inf. 13, 49–50 (2018).

IUCN. IUCN Red list categories and criteria: version 3.1. Accessed on. 2nd February (2024). http://www.iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/categories-and-criteria/2001-categories-criteria

Speybroeck, J., Beukema, W. & Crochet, P. A. A tentative species list of the European herpetofauna (Amphibia and Reptilia) - an update. Zootaxa 2492, 1–27 (2010).

Mutz, T. & Böhme, W. Ichthyosaura as a generic nomen for the alpine Newt (Caudata: Salamandridae): a doubtful case of literarian archeology. Salamandra 61, 41–52 (2025).

Esri Inc. ArcGIS Pro software (2025). https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview

R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (2025). https://www.r-project.org/

Dobson, R. et al. DynamicSDM: an R package for species geographical distribution and abundance modelling at high Spatiotemporal resolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 1190–1199. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14101 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We highly value the support provided by the Romanian Academy and Retezat National Park Administration and staff. We are grateful to our many friends and colleagues, family members, and volunteers for their support during fieldwork. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS/CCCDI-UEFISCDI, project PN-III-P4-PCE-2021-0818 (AlpChange). Part of the fieldwork was supported by the Ministry of European Investments and Projects, project SMIS 319225 “Întărirea capacităii pentru managementul adaptativ al capitalului natural din Parcul National Retezat (incluzând rezervaiile 2.494 Gemenele, 2.496 Pestera Zeicului) împreună cu siturile Natura 2000 suprapuse parial – ROSCI0217 Retezat si ROSPA0084 Muntii Retezat”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and data collection. GIS data management and the production of maps were the responsibility of CS and LR. The analyses were performed by DC, RIB, and LR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DC, and all authors commented on earlier versions of the manuscript. The figures and tables were prepared by DC, RIB, LR, and CS. All authors read and approved the revisions and the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cogălniceanu, D., Băncilă, R.I., Ghira, I.V. et al. Documenting six decades of change in herpetofauna occurrence patterns in a mountain ecosystem. Sci Rep 15, 41894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25871-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25871-y