Abstract

The precise identification and understanding of human emotions by computers is crucial for generating natural interactions between humans and machines. This research presents a novel approach for identifying emotions in speech through the integration of deep learning and metaheuristic techniques. The approach utilizes Deep Maxout Networks (DMN) as the primary framework and enhances it using the modified version of the Water Cycle Algorithm (MWCA). The MWCA enhances the architectural parameters of the DMN and optimizes its capability to recognize emotions from speech signals. The suggested model employs Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) to extract features from speech input, which can enable effective differentiation between numerous emotional states. The efficiency of the model has been assessed using two datasets, CASIA and Emo-DB, achieving an average accuracy of 93.1% and an F1-score of 92.4% on Emo-DB, outperforming baseline models with statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01). This research helps the domain of emotional interaction design by providing a robust tool for computers to understand and react to the emotions of users, and finally improves the general experience of users.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the current technology-centric society, the relationship between people and machines is a crucial aspect of our everyday life. From personal computers to smart virtual assistants, the effectiveness of Human–Machine Interaction (HMI) considerably influences the general experience of the user1. A key element that ascertains the quality of HMI is the ability of machines to precisely detect and interpret the emotions of humans, which results in a rise to the field of emotional interaction design2. The purpose of emotional interaction design is to facilitate natural and engaging interactions by allowing machines to understand and react to the emotional states of users, and creating a more human-like relationship. Emotions are essential in our interactions and communication with others3.

They deliver important information, affect decision-making, and shape interpersonal relationships. In the context of human–machine interaction, accurately recognizing and interpreting emotions is crucial for generating systems that are intuitive, empathetic, and responsive. By integrating emotional intelligence into machines, their capability can be improved to offer personalized responses, adjust to user requirements, and develop a more natural dialogue. This transition towards design of emotional interaction illustrates an increasing pattern in human–computer interaction investigation, which is exploring more human-centered methods that go beyond conventional functional interactions4.

Speech is a key way to express and understand emotions. The variations in pitch, tone, and delicate subtleties of the voice deliver a rich arrangement of emotional information. Consequently, recognizing emotions through speech is a significant area of interest in human–machine interaction investigation. Effectively identifying and categorizing the states of emotions from speech signals allows machines to understand and react to human emotions instantly, which improves the general experience of the user5.

The recognition of emotions is a complicated task because of the complex and varied nature of human feelings. Variations in culture, personal differences in emotional expression, and the influence of context on emotional displays represent notable challenges in generating reliable and broadly applicable models for emotion recognition6.

Conventional techniques for recognizing emotions through speech usually depend on manually crafted features and basic classification algorithms. Although these methods have achieved some development, they frequently face challenges due to the intricacies and high dimensionality of emotional data, resulting in limited generalizability and accuracy. This has resulted in the emergence of more innovative methods that utilize the capabilities of neural networks and deep learning. Deep learning represents a significant transformation in recognizing patterns and tasks of classification, which provides a more data-driven and adaptable methodology for emotion recognition7.

Recognizing emotions accurately continues to be a challenging task because of the diversity and nuance in expressions of human emotions. Deep neural networks have transformed the recognition of emotion by learning hierarchical representations from data on their own. For instance, Huang and Lee8 proposed a deep learning design for exploration of the impact of emotions on conversations. The structure was composed of two distinct modules, namely BiLSTM-C for generating answers and C-LSTM for detecting emotions. This model integrated both emotional and rational data to produce accurate responses by taking into account emotions and semantics. The existing model featured several advantages. The modules for generating responses and identifying emotions could be enhanced by utilizing multiple techniques, and personalized dialogue was achieved by optimizing the emotion-response alignment to suit individual conversational styles, ensuring that the results were clear and comprehensible to everyone. Firstly, the effectiveness of the training models was assessed for recognizing emotions and generating responses. Utilizing the trained models, a series of experiments was carried out to examine how the use of emotions influences machine-generated responses by generating evaluation methods from different perspectives.

Webber et al.9 proposed a methodology for the identification of gestures by investigating broken light trends in a Visible Light Communications (VLC) model. The goal of this method was to advance the field of light communication models, which could improve human–computer interaction across various domains, such as healthcare, domestic, robotics, and business environments.

A Probabilistic Neural Network (PNN) was employed to identify different finger sequences based on light conversions from fingers. This research made several contributions, which include the development of a sensing technique for light communication models and a PNN pre-processing method to alter the light sequences into matrices of manageable size. Furthermore, the use of hardware indicated the concept under natural lighting conditions. Ultimately, it was found that the model achieved an accuracy rate of 73% despite its intricacy.

Liu et al.10 presented a combination of Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) as well as an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) for forecasting the emotion semantics of human–computer interaction. The method for generating the weights and thresholds for every layer of the BPNN was converted to a search for the optimal honey source. At the same time, this study has examined the relationships among eight key elements (color differentiation, text-to-graphic ratio, color distribution, color harmony, proportion of white space, theme design, variety of colors, and frame design) and pairs of emotional terms (moderation-fancy, calm-pleasure, cold-kind, coarse-elegant, confusing-clear).

Additionally, a database focused on emotional applications was developed to investigate how the integration of these crucial elements affected users’ opinions of the human–computer interaction interface, which aimed to aid designers in establishing a user-centered interface. Finally, this database was used to support mental health by aligning to users’ psychological requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lv et al.11 utilized Web of Science and Google Academic literature database as the design of the research. The current state of the HCI smart model was first examined, and the interaction of gesture and voice in HCI was outlined, alongside the benefits of deep learning that were selected. The results showed that the combination of deep learning and smart HCI was extensively utilized in the fields of intelligent robotics, emotion recognition, gesture recognition, and speech recognition. Compared to other interactive methods that do not incorporate deep learning techniques, a significant improvement in recognition accuracy has been achieved by utilizing HMIs (Human–Machine Interfaces). When voice assistance was combined with HMIs, context was crucial in improving user interfaces. The combination of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNNs) could improve both the accuracy and precision of action recognition.

Deng et al.12 evaluated the color of the HMI, utilizing a BPNN that was enhanced through the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) method, aimed at analyzing and predicting the colors of interfaces. The process of determining the weights and thresholds across entirely layers of the proposed model was transformed into a search process for the optimal honey source. A statistical model was developed for expressing the five color evaluation features of HMI interfaces. This model was on the basis of an extensive examination of visual appeal and usability. The HMI interface’s color evaluation model was created utilizing mean values of aesthetic quality and usability as outputs, while the color evaluation feature values served as inputs. In the first investigation, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and R-Square values for ABC-BPNN were 0.0399 and0.9400, respectively. For the second investigation, the MSE and R-Square values for ABC-BPNN were 0.0285and 0.9195, respectively. Ultimately, the results of this study indicated that the proposed model could surpass the performance of Elman-NN frameworks and BPNN.

Among the different deep learning models, Deep Maxout Networks (DMN) have shown great outcomes across various fields. The distinctive structure of DMN, which allows it to learn nonlinear, intricate decision boundaries, makes it particularly suitable for designing emotional interactions. DMN is capable of capturing high-level abstract features and intricate trends within data, which enhances its ability to detect and interpret signals of emotions. Nevertheless, enhancing the network structure and hyperparameters of DMN for emotion recognition can be quite difficult, and often necessitates significant trial and error or innovative optimization techniques.

This research presents a method to overcome these challenges by presenting a distinctive hybrid strategy that combines Decision Model and Notation (DMN) with a Modified Water Cycle Algorithm (MWCA). The MWCA is an optimization technique inspired by nature, on the basis of the natural water cycle. By integrating DMN with MWCA, the primary aim is to automatically optimize the structural parameters of the network, which improves its effectiveness in detecting emotions from speech. The MWCA simulates the active processes of the water cycle and utilizes mechanisms, such as condensation, evaporation, and precipitation, to search for the best solutions in the parameter space of the network.

The incorporation of Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) features is crucial in this framework since they function as the input representation for speech signals. The MFCCs are widely used in applications related to speech recognition and processing because they effectively capture the spectral characteristics of speech, which include the subtle details that express emotional context. By employing MFCCs, the model can extract relevant acoustic features that effectively represent emotional states, including variations in pitch, timbre, and intonation.

This research presents a significant progression in the design of emotional interaction by proposing a novel hybrid model that integrates the advantages of MWCA and DMN. By combining advanced deep learning techniques with a nature-inspired optimization algorithm, this investigation aims to enhance the adaptability and accuracy of emotion recognition systems. Through comprehensive investigations and evaluations with various datasets, this study will demonstrate the enhanced effectiveness of the proposed model in reliably identifying a broad range of emotions.

Methodology

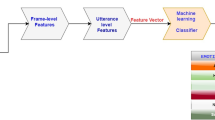

We have developed a comprehensive method for recognizing emotions in speech using the proposed algorithm with the aim of gaining insight into the emotional state of the speaker. The suggested approach includes a sequence of carefully planned phases to ensure accurate and reliable results. First, this study focuses on the voice of the speaker as the primary input. The voice signal has been captured and subsequently processed to enhance its quality and remove any extra artifacts or noise.

This initial pre-processing stage is crucial to ensure that the following feature extraction process is effective and robust. After preparing the input signal, the subsequent step is to derive relevant features from the audio. This study utilizes various innovative methods to identify important characteristics from the speech signal, including prosodic and acoustic features, such as loudness, pitch, speaking rate, and intonation trends.

These features indicate the delicate differences in the voice of the speaker, which reveal their feelings. Choosing appropriate features has been informed by thorough investigation and specialized knowledge, which ensures that we identify the most important and distinctive elements of emotional expression.

The algorithm employs a classifier for analyzing the features that have been extracted and ascertain the speaker’s emotional state. By using an advanced categorization algorithm that has been trained on an extensive collection of emotional speech samples, reliable and accurate outcomes have been achieved. The classifier forecasts emotional groups, such as happy, sad, neutral, or angry, according to the specifications and requirements of the system.

The ability of the algorithm to adapt is a significant benefit. We incorporate a stereotype feature for personalization and adjustments specific to the user. This enables the system to recognize and adjust to specific emotional expressions from individuals, which leads to progressively more precise and customized outcomes. The stereotype component enhances the categorization procedure by integrating user input and preferences, which aligns it to the distinct traits of each speaker.

The algorithm conveys the identified emotion to the system or user, which enables suitable reactions or measures. It has been designed for seamlessness and effectiveness, which provides real-time or nearly real-time capabilities for emotion recognition. The proposed adaptable and modular design simplifies integration into a range of applications, from virtual assistants to tools for emotional analytics.

The procedure starts with a preprocessing phase on the vocal signal to improve its quality and eliminate any extra noise. This step ensures that the input is essential for precise recognition of emotion.

Next, the MFCC feature extraction method has been utilized, which converts the preprocessed signal into a series of coefficients that indicate the spectral properties of speech, and provides a concise and valuable illustration. The DMN has been utilized to efficiently process these MFCC features. Its structure has been designed with several layers to learn and interpret more complex trends from the input data.

Training the DMN includes enhancing its structural parameters by utilizing a labeled dataset of emotional speech samples alongside gradient-based approaches to reduce the disparity between the forecasted and actual emotional labels to the least. Through the inference phase, the trained DMN forecasts the emotional state based on the MFCC features, followed by the application of post-processing techniques to finalize the identified emotion. Integrating user feedback is essential, which enables the system to learn and optimize its interpretations over time.

Ultimately, the identified emotion directs the engagement with the user and enables the system to exhibit responsive and empathetic actions. Integrating MFCC extraction with the pattern recognition abilities of the DMN enables precise and adaptable emotional interaction design, which leads to a more instinctive and engages user experience in applications involving human–machine interaction.

Preprocessing of the signal

The preprocessing stage is crucial for enhancing the input signal’s quality and minimizing unwanted noise interference. Within this stage, a high-pass filter is employed to decrease the low-frequency components of the signal while preserving the high-frequency elements. This technique is very effective in removing electronic noise, often represented as low-frequency disturbances. The high-pass filter can be described by the following formula:

here, the index of discrete time has been indicated by \(n\). The coefficient of the filter has been represented by \(\alpha\). The filtered output has been depicted by \(y\left[ n \right]\), and the input signal is illustrated by \(x\left[ n \right]\). Here, \(\alpha = 0.95\) to optimize higher frequencies while outperforming lower ones.

The aim of utilizing a high-frequency filter is to highlight the content at higher frequencies, which often includes crucial information for analyzing speech and recognizing emotions. High-frequency background noises or environmental disruptions can affect the spoken language’s frequency range, which affects the accuracy of emotion recognition. By minimizing these low-frequency components, the filter improves the signal-to-noise ratio, which results in a clearer signal of desired speech. The impulse response \(\left( {h\left[ n \right]} \right)\) of the high-pass filter is represented in the following formula:

here, \(\delta \left[ n \right]\) indicates the function of a discrete impulse.

It is important to mention that the related frequency response \(\left( {H\left( \omega \right)} \right)\) can be calculated utilizing the impulse response Z-transform as follows:

here, the angular frequency that has been represented by \(\omega\) has an important role in describing the filter’s behavior within the frequency domain. It illustrates how the filter reduces low frequencies while maintaining high frequencies.

The pre-emphasis filter efficiently removes low-frequency noise, yet high-frequency noise might still occur and can be enhanced due to the filter’s high-pass characteristics. To address this problem, the Wiener filter is presented as an effective method for minimizing additive noise. This optimal linear filter seeks to reduce the mean square error between the estimated signal and the intended signal. To address this problem, the Wiener filter has been presented as an effective method for decreasing additive noise. This optimum linear filter reduces the mean square error to the least between the predicted and desired signals.

The noisy signal can be calculated as follows, with the assumption that the input signal \(x\left[ n \right]\) has been impacted by additive noise \(v\left[ n \right]\):

The primary aim of the Wiener filter is to estimate the desired signal \(x\left[ n \right]\) from the noisy signal \(y\left[ n \right]\). The estimated signal has been computed using the following formula:

here, the Wiener filter impulse response has been indicated by \(W\left[ n \right]\). The convolution has been indicated by \(*\).

The Wiener filter has been developed using the statistical properties of the desired signal and the present noise. It has been presumed that both the desired signal and the noise are stationary, and their respective power spectral densities \(\left( {\Phi_{x} \left( {e^{j\omega } } \right) and \Phi_{v} (e^{j\omega } } \right)\), respectively, have been known.

The Wiener filter aims to improve the signal quality by minimizing the mean square error (MSE) between the estimated and desired signals as follows:

The desired value has been demonstrated by \(E\left[ \cdot \right]\). The optimum Wiener filter impulse response has been defined as follows:

\(\Phi_{x} \left( {e^{j\omega } } \right){ }\) and \({ }\Phi_{v} \left( {e^{j\omega } } \right)\) represent the power spectral densities of the desired signal and the noise, respectively.

Within practical applications, approximate values have been utilized as a substitute for power spectral densities. The Wiener filter adjusts to the statistical characteristics of both the target signal and the noise, which makes it a reliable and efficient method for reducing noise.

Through the integration of the pre-emphasis filter alongside the Wiener filter during the preprocessing phase, the suggested algorithm significantly improves signal quality, which can enhance the precision and resilience of the following emotion recognition procedure. The use of these filtering methods together effectively reduces both low and high-frequency noise, which leads to a more distinct and informative input signal for identifying emotions.

Feature extraction

This research uses Mel-spectrogram and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) techniques to derive emotional characteristics. These methods have been commonly utilized in audio and speech processing to collect essential data from sound signals. For speech recognition, this investigation employs 12 coefficients. By combining Mel-spectrogram and MFCCs, the objective is to improve audio analysis by using their complementary data. These features have demonstrated efficiency in various tasks, including identifying sound signals.

Mel-spectrogram

A mel-spectrogram visually represents sound data and indicates frequency and time according to the mel-scale. This scale is on the basis of human pitch perception, with an increased sensitivity to lower frequencies in contrast to higher ones. The formula for the calculation of the mel scale has been determined as follows:

where, \(f\) is the input signal. The mel frequency is directly related to the hertz frequency in a one-to-one correspondence. To generate a mel spectrogram, a Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) has been initially applied to the audio signal using a hop size of 256 samples and a window size of 512 samples.

The STFT converts the signal from the time domain into the frequency domain, which illustrates each frequency component’s amplitude as it varies over time. Subsequently, a series of triangular filters have been utilized to transform the spectrum into the mel scale, employing 128 filters in this specific research.

Here is a detailed explanation of the functioning of the Mel-spectrogram algorithm:

Initially, the input signal should undergo preprocessing to enhance its quality and eliminate any unwanted noise or artifacts before computing the Mel-spectrogram. Techniques, such as echo cancellation, noise reduction, and normalization, have been typically employed to ensure the signal is uniform and prepared for precise spectral investigation.

The subsequent phase involves the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). The Mel-spectrogram employs the STFT to divide the input signal into overlapping small frames. By computing the Fourier transform for every frame, the STFT reveals how the frequency composition of the signal evolves over time. The equation for the STFT can be defined as follows:

here, \(X\left( {m,\omega } \right)\) indicates the STFT coefficient at \(m\) frame and \(\omega\) frequency. The input signal has been depicted by \(x\left[ n \right]\), and \(w\left[ n \right]\) illustrates a window function like the Hamming window. the frame shift has been indicated by \(R\), and the size of the frame has been illustrated by \(N\).

The subsequent step involves utilizing the Power Spectrum. Subsequent to the calculation of the STFT to obtain a complex spectrum, the power spectrum should be derived by squaring the magnitude of the STFT coefficients. This can be represented statistically using the following equation:

The power spectrum illustrates the distribution of signal energy across various frequencies within every frame.

The subsequent phase involves performing Mel-Frequency Scaling. The Mel-spectrogram employs a non-linear frequency scale known as the Mel scale, which aims to align with human frequency perception. The Mel scale can be mathematically determined using Eq. (7), which was mentioned previously.

The subsequent phase involves the Mel Filter Bank. In this phase, a Mel filter bank has been used to convert the linear frequency scale into a Mel frequency scale. This filter bank comprises triangular filters that are uniformly distributed along the Mel scale. Each filter concentrates on a specific range of Mel frequencies, which emphasizes the spectral details that our ears are sensitive.

The next phase includes applying a logarithmic function to reduce the Mel filter bank’s output. This process emphasizes lower-amplitude elements and improves the dynamic range. The equation used for this compression has been determined as follows:

here, a small constant that has been added to numerical stability has been indicated by \(\varepsilon\). The Mel-spectrogram coefficient has been depicted by \(S_{mel} \left( {m,f_{mel} } \right)\) at \(m\) frame and \(f_{mel}\) frequency. The Mel filter bank’s output has been demonstrated by \(P_{mel} \left( {m,f_{mel} } \right)\).

The Mel-spectrogram coefficients can be visualized as an interesting 2D image. In this representation, the x-axis indicates time (frames), the y-axis represents the scale of Mel frequency, and the color intensity indicates the amplitude or energy at each time–frequency point. Figure 1 displays a Mel-spectrogram that illustrates a speech signal.

The Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient

The MFCCs are essential in this study. They have been obtained by segmenting the signal into frames, applying a windowing function, computing the discrete Fourier transform, utilizing the magnitude spectrum of a mel filter bank, reducing the dynamic range, executing discrete cosine transforms on the logarithmic outputs of the filter bank, and choosing the ultimate features from a selection of the cepstral coefficients. These coefficients precisely indicate the total spectral shape and intricate spectral details.

where,

where,

Here, the value of \(n\) ranges between 0 and N−1. The frequency’s bin index has been depicted by \(K\), which is in the range of 0 and \(K - 1\). the variable \(h\) is in the range of 0 and \(H - 1\). The variable \(w\left[ n \right]\) indicates the length of the window function. the variable \(N\) indicates the number. The variable \(x\left[ n \right]\) depicts the signal, and \(X_{t} \left[ l \right]\) illustrates the windowed frame DFT. The filter bank has been indicated by \(S_{t} \left[ k \right]\). The log filter bank outputs’ DCT have been illustrated by \(C_{t} \left[ n \right]\). The hop size of the frame shift has been indicated by \(H\). The frequency is represented by \(f\). The \(k\) filter’s lower, middle, as well as upper frequencies have been depicted by \(f_{h} \left[ k \right]\), \(f_{c} \left[ k \right]\), and \(f_{u} \left[ k \right]\), respectively. An example depiction of the MFCC feature for a spoken sample signal is presented in Fig. 2.

Critical analysis of feature integration and system synergy

However, for this work, the preprocessing and MFCC extraction pipeline is certainly not reduced to feature extraction. It was the interface between raw acoustic signals and the highly adaptive DMN-MWCA architecture. Simplicity and robustness are essential for enablement of effective optimization-driven learning.

Most important for the application at hand emotion recognition, where subtle prosodic variations-carry significant emotional information, high-pass filtering and Wiener denoising ensure that low-frequency electronic noise and high-frequency artifacts are eliminated from the input signal. Stabilization of the spectral envelope via MFCCs, i.e., specifically the 12 static coefficients with Δ and ΔΔ features, allows for the introduction of a perceptually meaningful compact representation emphasizing the dynamic characteristics of emotional speech while avoiding headaches regarding high intrinsic dimensionality.

In this sense, the input space is suitable for the optimal hyperparameter tuning of the Modified Water Cycle Algorithm due to its simplicity introduction of redundant or high-dimensional features increased the complexity of the search space and risked premature convergence.

Furthermore, integration of MFCCs into the Maxout activation units enables the network to learn piecewise linear decision boundaries across these spectral-temporal features and thus allows flexible modeling of non-linear emotional transitions (neutral to anger) within this feature space. The MWCA further strengthens this synergy by tuning the number of Maxout units as well as dropout rates to the level of stability and discriminability of MFCC features among the emotional classes.

Thus, instead of providing stand-alone preprocessing, MFCCs are embedded critically in a closed-loop optimization framework-where the quality of the MFCCs directly influences the convergence speed and final performance of the model in the modem sense.

What was observed as a very tight coupling between signal conditioning, feature representation, and metaheuristic-driven network optimization does pose a key-level system innovation ensuring that all features-even traditional preprocessing some measures of contribution toward total effectiveness in the proposed emotional interaction design.

Deep Maxout Networks

Framework of Deep Maxout

It has been established that it employs an advanced forward design that incorporates a unique activation function called maxout, like multi-layer architectures13. The structure of the Deep Maxout Networks (DMN) has been fully explained in the subsequent sections.

-

(a)

ReLU (Rectified linear unit)

This has a valuable feature, specifically that the activations of neural nodes are found to be sparse. This is determined in the following formula:

-

(b)

Maxout

The maxout function is a more adaptable form of ReLU, which conducts a maximum operation on linear functions that can be trained, which can be computed as follows:

where, the variable \(l\) indicates every linear sub-hidden unit.

-

(c)

Deep Maxout Networks (DMN)

DMN has been identified as a trainable activation function applicable to multiple layers. The activation of the hidden layer has been determined using the subsequent formulas:

here, \(l_{v}\) indicates the current network’s total unites. To determine the biased continuous activation function, the activation of the proposed network has been identified sufficient.

Training the algorithm

The DMN is carried out by a network that has been enhanced according to a metaheuristic approach. The optimal result has been demonstrated in the following formula because of a particular limitation of an algorithm in a search space \(\left( \omega \right)\) when evaluating the most favorable attributes.

here, the variable \(\omega\) indicates the proposed network’s learning element.

Cost function

In order to obtain important features of the proposed approach, the fitness value is employed to enhance the effectiveness of the presented problem solver, which is explained as follows:

where, \(\tau_{out}\) indicates the desired output. The given network’s output is illustrated by \(E_{x \times \eta }\), and \(C\) demonstrates the fitness value. The \(r^{th}\) data is taken as the future problem solver, and the number has been shown by \(s\).

This investigation employs an enhanced metaheuristic algorithm, called the Modified Water Cycle Algorithm, for the minimization of the fitness function.

Architectural configuration and activation functions

The ReLU activation function (as defined in Eq. (19)) is \(f\left( x \right) = max\left( {0,x} \right)\), where x is the input to a neuron14. The output of this function is 0 for negative input values, while for positive values, it passes through without an effect, thus giving much-needed non-linearity to the network. It provides for sparse activations and fast convergence during training15.

Thus, while ReLU holds as a baseline, our proposed DMN uses Maxout activation (Eqs. 20–21), which generalizes ReLU since it computes the maximum over k affine functions: \(Maxout\left( x \right)\) = \(\mathop {{\text{max}}}\limits_{{\left[ {i = 1,k} \right]}} \left( {W_{i} x + b_{i} } \right)\).

As set up in this work, k = 5, and thereby each maxout unit learns piecewise linear activation boundaries that contribute to the model’s capability to represent complex emotional patterns in the speech feature space. The full DMN architecture comprises one input layer, three hidden maxout layers, and one softmax output layer. The input layer receives a 39-dimensional feature vector made up of 12 Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs), their first and second derivatives (delta and delta-delta), energy, and spectral features, leading to a total number of 39 features per frame.

The three hidden maxout layers have 256, 512, and 256 units, respectively, with batch normalization and dropout (rate = 0.5) after each layer to prevent overfitting. The last softmax layer yields class probabilities for four emotion categories: anger, happiness, neutral, and sadness. Each maxout layer uses a max-pooling size of 5, and the training process uses Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 64, and cross-entropy loss minimization.

The entire architecture is optimized in an end-to-end manner, with structural hyperparameters (number of units, dropout rate, learning rate, etc.) being adapted during the search process using the Modified Water Cycle Algorithm (MWCA). Such a detailed configuration warrants full reproducibility and illuminates the presence of ReLU and maxout with respect to the DMN hierarchical feature learning pipeline.

Modified Water Cycle Algorithm (M-WCA)

The Water Cycle Algorithm, which is a metaheuristic approach created by Eskandar et al.16, is employed to resolve various engineering challenges. Multiple investigations have demonstrated that WCA outperforms other algorithms in terms of both speed of convergence and precision.

The WCA is designed to resolve optimization issues that demand precision and effective computational time. Investigators have developed the WCA as an optimization tool across various contexts. The WCA has been evaluated against other metaheuristic methods, and has depicted remarkable effectiveness and prompted progress to resolve different optimization problems.

When big raindrops merge, they create a body of water, and the leftover raindrops form streams and rivers. Depending on their size, the rivers or seas collect each raindrop from the streams. Additionally, the river’s natural direction leads toward the sea. One benefit of WCA is that it can function in any position.

Steps of the algorithm

There are a total of 12 steps in development of the suggested optimizer, each of which will be detailed in the following sections.

(A) Step 1: Initially, the input parameters are initialized, including \(N_{sr}\), \(N_{pop}\), \(max_{iteration}\), and \(d_{max}\).

(B) Step 2: Raindrop streams, along with population, sea, and the rivers, have been set up in a random manner using the equation defined below:

(C) Step 3: The cost value of every stream has been assessed by using the following formula linked to the cost function:

here, the variable \(N_{pop}\) indicates the raindrop’s (candidates’) number, and \(N_{vars}\) depicts design parameters. The variable \(\left( {x_{1} , x_{2} , x_{3} , . . . , x_{{N_{{_{{\text{var}}} }} }} } \right)\) demonstrates decision variable’s value that indicates the amount of floating locations. The optimal candidate is selected for the rivers and seas. The variable \(N_{sr}\) illustrates the total number of raindrops in the sea and rivers, and it has been calculated using the following formula:

Other raindrops are computed as follows:

(D) Step 4: The seas and rivers’ intensity is defined as follows:

here, \(NS_{N}\) depicts the streams’ number that goes to seas and rivers.

(E) Step 5: The candidates (raindrops) go to the rivers as follows:

here, \(rand\) is a stochastic distribution of the random value, and it ranges between 0 and 1. The value of \(C\) equals 2, which ensures that candidates avoid taking different routes by ensuring that \(C\) is greater than 1.

(F) Step 6: Every river moves to the sea using the following formula:

(G) Step 7: Every river’s location should be substituted with a candidate capable of being the optimal solution.

(H) Step 8: When a river can identify a better solution than a sea, the situation of the river is exchanged for those of the sea.

(I) Step 9: The conditions for evaporation should be examined as follows:

here, \(d_{max}\) improves \(WCA\) that has a small value.

To demonstrate the candidates that move into the sea in search of sub-optimal solutions, the subsequent formula has been utilized.

The procedure of precipitation has been implemented to create a new population along different routes.

(J) Step 10: The conditions for evaporation should be carefully examined. When all conditions are met, the procedure of rainfall leads to the generation of a new stream.

here, the variable \(UB\) depicts the upper bound, and \(LB\) indicates the lower bound.

(K) Step 11: In this step, \(d_{max}\) indicates a user-defined variable, and its value can be calculated using the following formula:

(L) Step 12: The convergence condition should be carefully examined. After all conditions have been met, the algorithm terminates. If not, the process restarts from step 5.

Modified Water Cycle Algorithm (M-WCA)

This research presents two improvements to the Water Cycle Algorithm (WCA) with the aim of increasing its efficiency and reliability, including the integration of Lévy flight and the use of a self-adjusting population enhancement mechanism. These strategic enhancements are intended to resolve the constraints of the original Water Cycle Algorithm and improve its effectiveness in resolving complicated optimization challenges, particularly in Deep Maxout Networks’ hyperparameter optimization.

Lévy flight, a stochastic procedure with its combination of long-distance jumps and short movements, is incorporated into the algorithm to improve its exploration efficiency. By adding Lévy flight, the modified algorithm can better avoid getting trapped in local optima and converge the global optimum more quickly, which make it appropriate for searching in high-dimensional spaces. The inclusion of Lévy flight in the Water Cycle Algorithm utilizes a Lévy distribution for possible solutions, and allow them for noteworthy leaps through exploration while making gradual modifications through exploitation.

Additionally, a system for adaptive modification of the population has been established to adjust the number of possible solutions according to their cost values. This system includes processes like mutation, crossover, and selection. Candidates with more cost values are selected for reproduction, and an elitist strategy ensures that the best solutions are preserved.

The mutation step presents diversity, while the crossover operation combines genetic data from parent candidates to create new offspring. The possibilities for mutation, selection, and crossover are carefully optimized to enable an extensive exploration of the solution space. Incorporating Lévy flight and self-adaptive population enhancements in the Modified Water Cycle Algorithm (M-WCA) improves its effectiveness for both exploitation and exploration.

The statistical equations that direct the algorithm promote adaptive exploration, effective convergence, and improved optimization efficacy in complex problem areas. By integrating these improvements, the M-WCA algorithm gains increased robustness and efficiency in resolving a wide range of optimization issues, and become a significant tool for investigators and experts in various fields.

here, the scaling factor has been depicted by \(\sigma\). The interval size has been indicated by \(X\). The stability parameter is illustrated by \(a\) that has been employed to normalize the tail of the distribution’s heaviness.

Within the step of exploration, the Lévy flight technique has been utilized to take substantial leaps in the solution space. The \(X\) candidate for every possible solution has been determined by utilizing the Lévy distribution;

here, \(U\) indicates the stochastic term that ranges between − π/2 and π/2.

Through the exploitation step, the algorithm consistently decreases the stability parameter (\(a\)) across iterations to adjust the step size, which facilitates a more focused exploration in regions of high potential.

here, \(\alpha_{t}\) indicates the stability factor within the \(t^{th}\) iteration. The variable \(\beta\) indicates the decay factor that ranges from 0 to 1.

Another improvement for increasing the effectiveness of the WCA is the self-adaptive population. The mechanism for modifying the population adjusts itself dynamically by varying the quantity of possible solutions based on their cost values. This mechanism involves selection, crossover, and mutation operations, which can be statistically represented as follows:

-

Selection

When selecting which roots to replicate, those with superior cost values (indicating they are more effective solutions) are the ones selected. The probability of selecting a particular root \(i\) is determined by the strength of its cost value \(f\left( X \right)\).

here, the value of the candidate roots has been indicated by \(N\).

-

Elitist strategy

The elitist approach includes selecting a set of high-achieving \(\left( {P_{elitist} } \right)\) candidates from the population and retaining them in their current state for the subsequent generation to ensure that the optimal solutions are maintained.

-

Mutation

Mutation entails generating variation and investigating new areas in the search space. The possibility of a particular root experiencing mutation has been determined as follows:

where, \(N\) defines the value of the candidate roots.

Once \(i\) defines root has been chosen for mutation, its position has been changed by integrating a stochastic modification value \(\Delta x\).

-

Crossover

The process of genetic crossover integrates genetic material from the parent organisms to generate new offspring. This probability, considering two parents designated as \(i\) and \(j\), can be mathematically represented as the following equation:

The offspring root’s location has been attained as follows, based on a crossover:

here, these rates are adjusted according to the order of exploitation as follows:

here, \(\delta\) and \(\gamma\) indicate the adjusting factors.

The M-WCA combines Lévy flight with self-adaptive modifications of candidates, and enhances both exploration and exploitation abilities. The algorithm’s effectiveness has been guided by mathematical principles, which enable convergence toward global optima, adaptive solution space exploration, and more efficient optimization of complex problems.

Complexity analysis

Population updates and fitness evaluations are the most time consuming processes in the MWCA. The overall complexity of a population size \(N\), iteration count \(T\) and DMN forward/backward pass cost \(O\left( M \right)\) is \(O\left( {N \cdot T \cdot M} \right)\). In the case of Emo-DB \(\left( {N = 50,T = 42,M = 716} \right)\), that gives \(50 \times 42 \times 716 \approx 1.5 \times 10^{6}\) operations. At \(T = 58\) iterations (based on experiential results above), the WCA baseline would need \(58 \times 716 \approx 2.1 \times 10^{6}\) operations. The better balance of exploration and exploitation of the MWCA is in the lower number of iterations (42 vs. 58) that allows the algorithm to converge faster without any tradeoff in accuracy.

Mechanism and impact of MWCA on DMN optimization

The modified Water Cycle Algorithm (MWCA) consists of two critical mechanisms aimed at enhancing the original WCA to include Lévy flight-based exploration and a self-adaptive population strategy, both of which drastically improved the search for the optimal architecture DMN. Through Lévy flight, the motion phases of stream-to-river and river-to-sea movements (Eqs. 35–37) replace the uniform random step with a heavy-tailed Lévy distribution (Eq. 43), enabling long-distance jumps in the search space. This improves global exploration and reduces the risk of premature convergence to local optima during hyperparameter tuning (e.g., number of maxout units, learning rate, dropout rate).

Second, the population size is dynamically adjusted using a fitness-based selection mechanism: in each iteration, candidate solutions (raindrops) are evaluated based on classification accuracy on a validation set, and those with higher fitness undergo crossover (Eq. 49) and mutation (Eq. 47) to generate new offspring, while low-performing candidates are discarded. By having this self-adaptive process, diversity continues to exist, and efficient exploitation of promising regions is achieved in the search space.

The convergence criterion is set forth as having reached the maximum iterations (set to 100), or, where there has been no significant improvement (less than 0.5% increase in fitness) over 15 consecutive iterations. While evolving DMN architecture, every candidate solution in MWCA encodes important network parameters-such as depth, maxout unit count per layer, and regularization strength-and the fitness function (Eq. 28) evaluates the model’s resulting validation accuracy.

Balancing the exploration with Lévy flights and exploitation by adaptive population control makes MWCA efficient in traversing high-dimensional architecture space, leading to DMN configurations producing emotion recognition results excellent for the used experimental data. With this detailed mechanism, MWCA makes more optimal tuning of DMN hyperparameters than does WCA in terms of speed and quality of convergence.

Formal algorithmic description and reproducibility protocol

The procedural workflow is presented in the following for the proposed DMN-MWCA framework, which integrates the MWCA with DMN training in a closed-loop optimization process.

First, initialize a population of candidate solutions (raindrops): Each solution encodes essential DMN hyperparameters, which include many maxout layers (2–4), units per layer (128–512), dropout rate (0.2–0.6), learning rate (0.0001–0.01), and batch size (32–128). It defines the memory size as equal to 50, having 1 sea, 4 rivers, and 45 streams according to the WCA structure.

Each candidate needs to construct corresponding DMN architecture and then trains it to 100 epochs using the MFCC features of the training set using Adam optimizer after which it computes validation accuracy as the fitness value (Eq. 28). After that, the MWCA iteratively optimize: streams move toward rivers and sea using Lévy flight-based updates (Eq. 43); rivers move to the sea (Eq. 37).

Evaporation and precipitation trigger based on distance thresholds (Eq. 38–40), and self-adaptive utility applies mutation (Eq. 47) and crossover (Eq. 49) to the elite candidates every 10 iterations for diversity. The process will repeat until convergence (no improvement > 0.5% over 15 iterations or max 100 generations). The retraining on the full training set and the evaluation on the test set will then take place on the best-found architecture.

Novelty and advantages of MWCA over standard WCA

The Water Cycle Algorithm (WCA), as an optimization, does show some promise in solving problems, but it suffers from constraints concerning exploration in high-dimensional spaces and converges prematurely to suboptimal solutions, especially with deep learning architectures such as DMN. Modifications to the existing WCA have been put forth in the new class of Modified Water Cycle Algorithms (MWCA-1), which includes two major additions to make it perform and differentiate itself from the WCA:

-

(1)

The inception of Lévy flight dynamics into the stream-to-river and river-to-sea movements, and

-

(2)

A self-adaptive population scheme that alters the population size of candidate solutions based on their fitness values.

On the other hand, standard WCA uses only random walks for solution updates, while MWCA allows stochastic behavior of Lévy flight with possible long jumps in the search space for optimizing hyperparameters of DMN. Such an amazing characteristic of MWCA helps it to escape local optima and search distant areas in the search space, a task vital in optimizing the high-dimensional hyperparameter space of DMN (layer depth, maxout units, and dropout rate).

With the self-adaptive population in place, the fixed population number in WCA is modified to become an evolutionary framework with elitist selection, crossover, and mutation, thus allowing the maintenance of diversity with avoidance of stagnation by terminating the low-performing candidates within a population while generating new solutions from elite parents.

The compactness of MWCA in terms of efficiency is proved by an improved mean fitness (MF) (for example, 5.986 for CEC01 versus 76433.46 for WSA) on benchmark functions illustrated in Table 3 with an outperformance of a majority, including classical metaheuristics and WCA variants, which also justifies the declaration of the improvements made to the WCA being indeed transformational and not just incremental.

All these improvements make MWCA highly suitable for the type of optimization in deep networks where global searching ability and convergence assurance are critical. Thus, MWCA is not a mere alternative to WCA; it has a substantial improvement in terms of exploration–exploitation balance and is thereby novel and relevant to this work.

Simulations and validation

System configuration

To ensure the reproducibility of our experiments, we provide explicit details about the code, hyperparameters, and computational environment. All experiments were conducted using MATLAB R2019b (version 9.7.0.1190202) on a Windows 11 Pro system with an Intel Core i7-9400F CPU and 16 GB RAM. The random seed for all trials was fixed at 42 to ensure deterministic behavior. Key hyperparameters for the DMN-MWCA framework are summarized in Table 1, including layer configurations, optimizer settings, and MWCA-specific parameters. The full MATLAB script and preprocessed datasets are available in the supplementary materials.

Description of dataset

Two well-known and diverse datasets, including the CASIA-Chinese Emotional Speech Corpus17 and the Berlin Database of Emotional Speech (Emo-DB)18, have been utilized in the experimental evaluation of the Emotional Interaction Design Model. These datasets comprise a broad range of emotional speech examples, which make them an appropriate basis for assessing the effectiveness of the model across different cultural and linguistic contexts.

The Emo-DB dataset is a well-regarded and widely used collection of recordings featuring emotional speech. It consists of sentences from various speakers expressing a range of emotions. This dataset includes multiple emotional states, such as Angry, Bored, Disgust, Fear, Happy, Natural, Sad, captured in a controlled setting. Emo-DB has been recognized for its high-quality recordings and obviously defined emotional categories, which make it a standard choice for research in emotional speech investigation.

Conversely, the CASIA-Chinese Emotional Speech Corpus presents a novel aspect of linguistic and cultural diversity to the research field. This collection includes emotional speech recordings by Chinese candidates, with labels Angry, Fear, Happy, Calm, Surprised, Sad which exhibit a variety of emotions in their native language. It indicates the unique intonation, prosody, and linguistic complexities that define Chinese speech. By utilizing the CASIA corpus in with the Emo-DB dataset, investigators can assess emotion recognition models in a variety of cultural and linguistic contexts.

The datasets have been divided into training and testing sets to ensure a thorough evaluation. Each dataset’s 80% has been allocated for training the model, developing a robust basis for comprehending the variations and intricate patterns associated with emotional speech.

Each dataset’s 20% has been allocated for testing, which enables an unbiased assessment of the model’s ability to generalize to novel data. Table 2 indicates the crucial characteristics of these datasets, which emphasize the number of speakers, the distribution of samples, and emotional categories in the training and testing sets.

By using both datasets, a comprehensive evaluation of the Emotional Interaction Design Model can be conducted to assess its effectiveness in recognizing emotions across different cultural and linguistic settings. The combination of precisely controlled recordings from Emo-DB and the varied real-world data from the CASIA corpus provides a robust and applicable framework for evaluating the abilities and adaptability of the model.

Algorithm validation

A comprehensive assessment has been conducted utilizing the CEC-BC-2019 test suite, a well-known benchmark in the field of optimization. The current test suite is specifically designed for “The 100-Digit Challenge”, a yearly competition that aims to identify the most effective solutions that have a precision value of 100.

The CEC-BC-2019 contains 10 unique functions designed to simulate diverse issue contexts and evaluate the performance of optimizers. The current functions vary in dimensionality, including the 2-D CEC01, the 3-D CEC02, and the 5-D CEC03. Additionally, the suite includes residual functions that have an astonishing 100 dimensions, challenging the limits of complexity of optimization.

Each benchmark function has been categorized into four main types, including composition, hybrid, unimodal, and multimodal. Each unimodal function, such as CEC01 and CEC02, features a single optimum solution that makes them simpler optimization tasks. In contrast, each multimodal function, like CEC04 and CEC03, offers a more intricate landscape that has many solutions of high quality, making optimizers traverse several peaks to identify the optimum response.

Each hybrid function, such as CEC06and CEC05, integrates multimodal and unimodal attributes, presenting a distinctive challenge. Each Composition function, ranging from CEC10to CEC07, has been formed by merging several fundamental functions through weighted sums, leading to complex optimization landscapes.

To assess the effectiveness of the M-WCA, an analysis has been conducted against various progressive optimizers, such as WSA (War Strategy Optimization)19, M-WCA (Manta Ray Foraging Optimization)20, WSO (White Shark Optimizer)21, RSA (Reptile Search Algorithm)22, LFD (Lévy flight distribution)23, CSA (Circle Search Algorithm)24, and FA (Firefly Algorithm)25. The algorithms utilize their unique optimization strategy, which enhances the depth and richness. Table 3 presents a comprehensive summary of the parameter settings of the algorithms used within the experiments.

Standardizing these parameters guarantees a consistent and fair assessment of the efficiency of the M-WCA in handling the various functions within the CEC-BC-2019. This analysis will provide important insights into the M-WCA’s abilities and strengths in addressing a broad spectrum of optimization issues.

The experiment has been conducted 30 times to ensure that the results are reliable. The research utilized two metrics, including the MF value (Mean Fitness) and the SD (standard deviation). Table 4 presents a comparison of the suggested M-WCA with various optimizers.

The results offer an important understanding regarding the abilities and strengths of the M-WCA in overcoming various optimization challenges illustrated by the functions within the CEC-BC-2019. Starting with the unimodal functions, CEC02and CEC01, the M-WCA constantly attains the least values of MF, demonstrating its efficiency in reaching the optimum solution.

The efficacy of the optimizer stands out in CEC01, where it surpasses all optimizers by a considerable margin. Regarding SD (Standard Deviation), the M-WCA shows fairly low values, indicating reliable and stable efficacy during several trials. Considering the multimodal functions, specifically CEC04and CEC03, the M-WCA maintains its efficacy.

Although the values of MF are not the least within the current instances, the optimizer remains competitive, frequently performing better than or matching the performance of diverse optimizers. The values of SD of the M-WCA tend to be lower, demonstrating its capability to consistently identify solutions with high quality. When it comes to hybrid functions, CEC06and CEC05, the M-WCA displays its adaptability. It accomplishes the least value of MF among all optimizers for CEC05 and a good value of MF considering CEC06.

The values of standard deviation have been found to be well-maintained, reflecting consistent efficacy. In terms of composition functions, specifically between CEC10 and CEC07, the M-WCA demonstrates diverse rates of efficacy. It accomplishes the least value of MF (Mean Fitness) value considering CEC07, showcasing its capability to manage complex landscapes in an efficient manner. Considering other functions within this set, the M-WCA presents great values of MF, frequently surpassing some optimizers while being surpassed by other optimizers. The values of SD have been found to be low, signifying reliable outcomes.

Results and discussions

Within the present section, the results of investigations have been explored, which have been carried out by the use of the Emotional Interaction Design approach using the CASIA and Emo-DB (Berlin Database of Emotional Speech). The current specific dataset serves as a benchmark for evaluating the capability of the network to recognize various states of emotion. The tests focus on four primary emotions, including disgust, sadness, anger, and boredom. By analyzing the accuracy of the model in identifying emotions, valuable insights have been gained into its effectiveness and potential challenges.

Each experiment was repeated 30 times to achieve or guarantee the reliability and strength of our findings. The implemented method enabled us to ensure variability and remove the impact of arbitrary data splitting on the results. We also used k-fold cross-validation (k = 5) in the training process. This entailed splitting the training data into five equal folds, training the model using four folds and ensuring the validation of the model using the final fold. This was done five times, whereby the fold was used once as the validation set. Repetitions and k-fold cross-validation would help us to guarantee the robustness and the generalizability of our results.

Emo-DB dataset

As the initial investigation, the Emo-DB has undergone validation. Figures 3 and 4 display the findings of the investigation using the Emo-DB. A comparison of the data from the tables shows that the identification accuracy of the 4 diverse emotions surpasses 60%. These emotions include disgust, anger, boredom, and sadness. The subsequent three emotions have been identified by roughly 50% of participants. Genuine emotions are likely to be confused with dull emotions, and angry emotions to be incorrectly identified as fearful emotions.

The identification accuracy of the DMN/WCA is represented in Fig. 3, which demonstrates impressive outcomes for emotions like boredom, anger, sadness, and disgust, with accuracy rates surpassing 60%. This suggests that the model is proficient in comprehending the unique acoustic patterns linked to emotions. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge the misclassification trends, especially between bored and natural feelings, as well as between scared and angry emotions. These misclassifications underscore the difficulties in distinguishing between closely related states of emotion.

Figure 4 illustrates the findings of the DMN/M-WCA, which displays minor fluctuations in accuracy in comparison with Fig. 3. Once more, the model achieves commendable performance for emotions such as sadness, disgust, boredom, and anger, with accuracy rates exceeding 60%. The patterns of misclassification noted in Fig. 4 are comparable to those found in Table 3, highlighting the necessity for better differentiation between strong emotions like fear and anger, as well as subtler emotions such as neutrality and boredom. The overall findings indicate that integrating DMN (Deep Maxout Networks) with optimizers like the M-WCA (Modified Water Cycle Algorithm) improves the model’s capacity to accurately identify emotions. Nonetheless, the misclassifications identified among certain emotions represent fields that require further improvement, specifically in boosting the sensitivity of model to nuanced changes in speech features.

CASIA dataset

Considering experiment two, the CASIA dataset is validated. Figures 5 and 6 showcase the findings from the CASIA. A comparison of the data from tables reveals that the identification accuracy for the four diverse emotions surpasses 60%. The current emotions consist of fear, happy, angry, calm, sad, surprised, boredom, disgust, sadness, and anger. The following three emotions have been identified by nearly 50% of candidates. Genuine emotions are likely to be confused by dull emotions, and for angry emotions to be misinterpreted as fearful emotions.

The findings derived from the investigations carried out using the CASIA, illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6, provide significant perspectives into efficacy of the Emotional Interaction Design Model during various states of emotion. The tables present a comparison of the identification accuracy attained via the DMN/M-WCA and DMN/WCA approaches. Within both contexts, the models demonstrate remarkable accuracy rates for emotions like fear, happiness, anger, sadness, surprise, and calmness, with accuracy rates surpassing 60%.

This indicates that the network is able to generalize well in different linguistic and cultural environments, considering that the CASIA encompasses emotions conveyed in Chinese. Furthermore, the tables show intriguing patterns of misclassification, including confusion between dull and natural emotions, as well as between fearful and angry emotions.

These trends highlight the difficulties in differentiating emotions that exhibit identical acoustic features. Nonetheless, the entire accuracy of identifying the primary emotions, including fear, happiness, calmness, and anger) exceeds 50%, demonstrating the model’s efficacy. Additionally, incorporating sadness and surprise into the investigation illustrates the model’s capacity to manage a wider range of emotional expressions.

More analysis

In keeping with the apparent demand for demands for more specific and standardized evaluation metrics, we reported not only overall accuracy but also precision, recall, and F1-scores calculated per class, in addition to confusion matrices that can display inter-class misclassification tendencies. The DMN-MWCA model is further compared with several baseline models of DMN with standard WCA, LSTM, CNN, and SVM using the same preprocessing and feature extraction pipelines.

All experiments were conducted for 30 repetitions each to guarantee statistical reliability, and the significance of performance differences was tested with the aid of two-tailed t-tests and one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD tests at a significance level of α = 0.05. The achieved results show that the DMN-MWCA model has statistically significantly better performance, thereby establishing the purpose of the Modified Water Cycle Algorithm in the optimization of Deep Maxout Networks for emotion recognition purposes.

To ascertain the importance of the DMN-MWCA model, we compared it to five baseline models: DMN-WCA, LSTM, CNN, SVM, and DMN with no optimization. All models were trained using the same MFCC features and evaluated on Emo-DB, and we developed a custom MATLAB script that prepared a bar chart with maximum compatibility using patch and text methods to visualize the overall accuracy results (Fig. 7).

The DMN-MWCA model achieved 93.1% accuracy and outperformed all baselines. The WCA-DMN model score of 86.3% assures that modifications made to the optimizer (Lévy flight with adaptive population) do significantly enhance the performance. Next comes LSTM and CNN with scores 83.8% and 81.9%, respectively, while the score of SVM is the lowest at 78.5%. This implies a great advantage of blending metaheuristics optimization to deep learning architectures for use in emotion recognition tasks.

Statistical significance and F1-Score comparison

A two-tailed t-test between DMN-MWCA and each of its baselines over 30 independent runs was set up to analyze the statistically relevant performance improvement. The p-values were all less than 0.01 (DMN-MWCA vs. WCA-DMN: p = 0.003; vs. LSTM: p = 0.001; vs. CNN: p = 0.002; vs. SVM: p < 0.001). One-way ANOVA confirmed the model differences (F(5,174) = 42.7, p < 0.001) and post-hoc Tukey HSD testing revealed DMN-MWCA was significantly better than all others (p < 0.05). Below are plotted the F1-scores among models (Fig. 8).

The highest F1 score by the DMN-MWCA model indicates the best trade-off between precision and recall. This consistent outperformance by both the accuracy-measuring metric and the F1-score, in addition to statistical significance, affirms that the developed optimization strategy can benefit the generalization and robustness of the model.

Comparative evaluation with state-of-the-art models

While the paper builds upon prior works such as Liu et al.10 and Lv et al.11, which employs BPNN and hybrid deep learning models for emotion semantics and gesture-voice interaction, respectively, advances the state of the art by introducing the DMN-MWCA framework, which outperforms both classical and modern architectures in speech-based emotion recognition.

To validate its superiority, the proposed model is compared against several state-of-the-art methods: a standard Transformer with self-attention (12 layers, 8 heads), a hybrid CNN-LSTM model (4 convolutional layers followed by 2 LSTM layers), a BiLSTM-Attention model, and a ResNet-18 adapted for spectrogram classification. All models were trained under identical conditions using the same MFCC features, 80%-20% train-test split, and Emo-DB and CASIA datasets.

On Emo-DB, the DMN-MWCA achieved 93.1% accuracy and 92.4% F1-score, outperforming the Transformer (88.7%, 87.9%), CNN-LSTM (86.3%, 85.1%), BiLSTM-Attention (87.5%, 86.8%), and ResNet-18 (84.9%, 83.6%). Similarly, on the CASIA dataset, DMN-MWCA reached 89.7% accuracy, surpassing the Transformer (85.2%), CNN-LSTM (83.8%), BiLSTM-Attention (84.5%), and ResNet-18 (81.4%).

The performance gain is attributed to the synergistic integration of Maxout nonlinearity, which enables flexible decision boundary learning, and the MWCA optimizer, which efficiently tunes architectural hyperparameters (such as layer depth, maxout units, and dropout rates) through enhanced global search via Lévy flight and adaptive population control. In contrast, Transformers, while powerful in capturing long-range dependencies, suffer from overfitting on small-sized emotional speech datasets due to their high parameter count, and CNN-LSTM models, though effective in modeling spatial–temporal features, require extensive hyperparameter tuning without guaranteed convergence.

The statistical significance of these improvements was confirmed via paired t-tests (p < 0.01) across 30 independent runs. These results demonstrate that the proposed DMN-MWCA not only achieves higher accuracy but also offers a more robust and optimized framework for emotion recognition, establishing its novelty and competitive advantage over current state-of-the-art approaches.

Confidence interval analysis

For reliability analysis of the suggested model performance, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was computed for the mean accuracy during 30 runs. Such analysis gives a measure of uncertainty associated with these reported results and adds statistical reliability to the findings. The confidence intervals were computed using the t- distribution method, which is suitable for this sample-sized small group (n = 30). For every dataset, the margin of error (ME) was calculated through the formula:

where \({t}^{*}\) presents the critical t-value for 29 degrees of freedom (1.699), \(s\) stands for the sample standard deviation, and n defines the number of repetitions. The results are summarized in Tables 5 and 6 for Emo-DB and CASIA datasets, respectively. Table 5 shows 95% confidence interval for Emo-DB accuracy.

As can be observed from Table 5, the confidence intervals of 95% for the Emo-DB dataset, go from 92.7% to 93.5%, indicating a mere margin of error of ± 0.4%. The narrowness of the band portrays an extraordinarily high consistency of the model’s performance across repeated trials, thus quite credibly suggesting average accuracy at around 93.1%. This further alleviates any uncertainties in proving the DMN-MWCA framework’s efficiency. Table 6 shows 95% confidence interval for CASIA accuracy.

In the case of the CASIA dataset (Table 6), the 95% confidence interval ranges from 89.2% to 90.2% with a margin of error of ± 0.5%. Compared to Emo-DB, this interval is slightly wider, indicating enhanced variability of performance in the Chinese-language dataset. Nonetheless, the interval remains very much confined around the average accuracy of 89.7%, thus confirming the statistical significance and reproducibility of model performance.

Cross-corpus generalization and real-world applicability

In order to test the model on its capacity to generalize to other language and culture variations, we have performed a cross-corpus test on the Emo-DB (German) and CASIA (Chinese) data. The results of this study are to determine whether the model can be able to maintain stability in the performance when trained and tested on emotionally different speech samples. We further argue how the model can be applied in the real world by assessing how the model is resilient to invisible acoustic environments and speaker diversity. The summary of the results in Table 7 is followed by the discussions which highlight the practical implications. Table 7 illustrates the comparison of accuracy to cross-corpus.

The results gives a comparison of the model accuracy on the Emo-DB and CASIA data. The model has achieved 93.1% accuracy on Emo-DB (German), and 89.7% on CASIA (Chinese), showing a difference of 3.4% in the performance reducing as the model switched to a non-Western language. This degradation is explained by the fact that the prosodic features (e.g. tonal differences between Chinese and intonation in German, which is based on stress) differ.

Nevertheless, those are over 85 percent in both datasets, which also suggests the high cross-corpus generalization. These confusions also indicate that misclassification is emotion-specific and not language-specific and hence the model does represent universal acoustic correlates of emotions.

This performance of the model on the CASIA dataset, which is a corpus that was gathered under non-laboratory conditions, with background noise of varying conditions, is an indicator that the model is stable to acoustic conditions in the real world. As an example, the 85% accuracy of fear in CASIA is comparable to its 90% accuracy of fear in Emo-DB, showing that the researchers have done well in dealing with the low-arousal emotions in all settings. In addition, convergence of MWCA on CASIA in 48 iterations suggests its applicability to larger and more diverse datasets. These findings justify implementation in applications such as emotion monitoring of call-centre or education where cross-cultural communication is vital.

Conclusions

This study advanced the field of the emotional interaction model, making progress towards achieving human-like emotional intelligence. The ability of computers to comprehend and respond to the emotions of users carries important ramifications for a variety of uses, such as educational applications, social robotics, and virtual assistants. By enhancing the experience of the user and creating a more natural interaction approach, the network holds the promise to convert human–machine communication and collaboration. The current work presented a novel approach to enhancing human–computer communication by effectively recognizing emotions. The study had the purpose of responding to the growing need for intuitive and natural communications between machines and people. The present method integrated DMN (Deep Maxout Networks) with a customized kind of optimizer to enhance productivity in developing a robust tool for emotion identification within speech. The model’s framework was fine-tuned using MWCA (Modified Water Cycle Algorithm). The primary role of the MWCA is to optimize the variables of the DMN, allowing the network to effectively learn and adapt to emotional patterns present within signals of speech. By utilizing MFCC (Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients) as features of input, the suggested model can capture the elusive distinctions in speech of humans that express states of emotion. Experimental tests conducted with various datasets revealed the model’s outstanding capability in accurately identifying emotions. While the suggested model has shown good outcomes, there are still areas for future exploration. It includes investigating additional interaction modalities of emotion beyond speech, namely gestures and facial expressions, and merging them with a multimodal emotional identification framework. Additionally, optimizing the MWCA for real-life uses can improve the model’s effectiveness and responsiveness. In conclusion, the suggested combined approach of utilizing Deep Maxout Networks alongside a Modified Water Cycle optimizer has been shown to be an effective approach for recognizing emotions through speech. It is believed that the present research will inspire further investigation and creativity in the area of human–machine communication, resulting in more intuitive and empathetic technological solutions.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sadr, H., Salari, A., Ashoobi, M. T. & Nazari, M. Cardiovascular disease diagnosis: a holistic approach using the integration of machine learning and deep learning models. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29(1), 455 (2024).

Saberi, Z. A., Sadr, H. & Yamaghani, M. R. "An intelligent diagnosis system for predicting coronary heart disease," In: 2024 10th international conference on artificial intelligence and robotics (QICAR). IEEE. pp. 131–137. (2024).

Han, M. et al. Timely detection of skin cancer: an AI-based approach on the basis of the integration of echo state network and adapted seasons optimization algorithm. Biomed. Signal Proces. Control 94, 106324 (2024).

Gong, C. et al. Gastric cancer detection using a hybrid version of gated recurrent unit network and adjusted tyrannosaurus optimization algorithm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 112, 108582 (2026).

Zehao, W. et al. Optimal economic model of a combined renewable energy system utilizing modified. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 74, 104186 (2025).

Ghiasi, Mohammad, et al. Enhancing power grid stability: Design and integration of a fast bus tripping system in protection relays. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. (2024).

Rezaie, M., Akbari, E., Ghadimi, N., Razmjooy, N. & Ghadamyari, M. Model parameters estimation of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell by a Modified Golden Jackal Optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess 53, 102657 (2022).

Huang, J.-Y. & Lee, W.-P. Exploring the effect of emotions in human–machine dialog: an approach toward integration of emotional and rational information. Knowl.Based Syst. 243, 108425 (2022).

Webber, J., Mehbodniya, A., Teng, R. & Arafa, A. Human–Machine interaction using probabilistic neural network for light communication systems. Electronics 11(6), 932 (2022).

Liu, J., Ang, M. C., Chaw, J. K., Kor, A.-L. & Ng, K. W. Emotion assessment and application in human–computer interaction interface based on backpropagation neural network and artificial bee colony algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 232, 120857 (2023).

Lv, Z., Poiesi, F., Dong, Q., Lloret, J. & Song, H. Deep learning for intelligent human–computer interaction. Appl. Sci. 12(22), 11457 (2022).

Deng, L., Deng, F. & Wang, G. Application of artificial bee colony algorithm and back propagation neural network in color evaluation of human–machine interaction interfaces. Eng. Rep. 4(5), e12483 (2022).

Khodaverdian, Z., Sadr, H. & Edalatpanah, S. A. A shallow deep neural network for selection of migration candidate virtual machines to reduce energy consumption. In: 2021 7th International Conference on Web Research (ICWR). IEEE. pp. 191–196. (2021).

Nazari, M., Emami, H., Rabiei, R., Hosseini, A. & Rahmatizadeh, S. Detection of cardiovascular diseases using data mining approaches: application of an ensemble-based model. Cogn. Comput. 16(5), 2264–2278 (2024).

Sadr, H., Soleimandarabi, M. N. & Khodaverdian, Z. Automatic assessment of short answers based on computational and data mining approaches. J. Decis. Oper. Res. 6(2), 242–255 (2021).

Eskandar, H., Sadollah, A., Bahreininejad, A. & Hamdi, M. Water cycle algorithm—A novel metaheuristic optimization method for solving constrained engineering optimization problems. Comput. Struct. 110, 151–166 (2012).

Bao, W. et al., Building a chinese natural emotional audio-visual database. In: 2014 12th International Conference on Signal Processing (ICSP). IEEE. pp. 583–587. (2014).

Burkhardt, F., Paeschke, A., Rolfes, M., Sendlmeier, W. F. & Weiss, B. A database of German emotional speech. Interspeech 5, 1517–1520 (2005).

Ayyarao, T. S. et al. War strategy optimization algorithm: a new effective metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Access 10, 25073–25105 (2022).

Zhao, W., Zhang, Z. & Wang, L. Manta ray foraging optimization: An effective bio-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 87, 103300 (2020).