Abstract

Dissimilar metal welding between titanium alloys and stainless steels presents significant challenges due to the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds (IMCs) at the interface, which compromise mechanical integrity. This study addresses these issues by investigating the interfacial microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of gas tungsten arc welded (GTAW) Grade 6 Ti alloy and Stainless Steel 304 joints using different interlayers. Three interlayer configurations, including Nb, Nb-Cu, and Ta-Cu were evaluated to suppress IMC formation and enhance joint performance. The results revealed that interlayer composition critically affects microstructural and mechanical properties. The Nb interlayer causes the formation of brittle TiFe and TiFe₂ phases as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), which resulted in interfacial cracking and reduced ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of 173 MPa, and elevated microhardness to 380 HV. In contrast, the Nb-Cu interlayer encourages the development of a Cu-rich solution, which increases UTS to 293 MPa and reduces microhardness to 106 HV. The Ta-Cu interlayer yields the most significant improvement in joint strength by attaining a UTS of 450 MPa, i.e., increases of 61.55% and 34.88% compared to the Nb and Nb-Cu interlayers, respectively. This enhancement is attributed to the formation of ductile microstructures containing Ta dendrites and Cu-enriched regions along with Fe₅Ta₃ and Ta₂Cu IMCs having a microhardness of 107 HV. X-ray diffraction further confirmed the suppression of brittle TiFe and TiFe₂ phases in Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu interlayered joints, corroborating the SEM/EDS findings. Fractographic analysis indicated improved metallurgical bonding and ductile fracture characteristics in Ta-Cu joints, highlighting their potential for enabling high-performance dissimilar welding of titanium and stainless steel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Manufacturing dissimilar welded joints is getting attention in modern age industries due to the combined advantages of joining base metals1. Dissimilar welded joints between titanium and stainless steel are used in industrial sectors, including nuclear, petrochemical, and aerospace due to the integration of high strength-to-weight ratio of titanium alloys and cost effectiveness and excellent corrosion resistance of stainless steel, yielding parts with ideal mechanical characteristics for specific applications2,3. The hybrid joining of these alloys has applications in cryogenic plumbing, oil rigs, and airplane engine blades to discs4. However, the major challenge in joining these metals is to avoid the development of TiFe, Ti2Fe, and Fe2Ti brittle intermetallic phases due to differences in thermal and physical properties. These phases degrade the mechanical as well as microstructure properties of the joints5. Due to these metallurgical issues, the desired strength of Steel (Fe) and Titanium (Ti) welded joints without an interlayer material is hard to achieve. Therefore, a suitable filler metal or interlayer with physical and thermal characteristics compatible with the base metals must be used to avoid the direct mixing of base metals and the formation of brittle phases in the fusion zone6,7.

Previously, researchers have conducted studies on dissimilar joining using a single interlayer/filler metal to evaluate the joint performance. Zhang et al.8 investigated the performance of pulse laser-hybrid titanium TC4 and stainless steel SUS301 L joints by incorporating a niobium interlayer. Results revealed an intermetallic reaction layer between stainless steel and niobium interfaces with Fe7Nb6, Fe2Nb compounds, whereas no intermetallic phases were found between titanium and niobium interfaces. Moreover, the fracture occurred at the intermetallic reaction layer zone, which has a maximum tensile strength of 370 MPa. Using copper-based filler wire and the GTAW technique, Hao et al.9 investigated the mechanical and microstructural characteristics of titanium TC4 and stainless steel 304 lap junctions. Fe melted in the Ti/Cu reaction zone due to the high heat input, forming intermetallic complexes TiFe and TiFe2, which decreased the mechanical characteristics. Furthermore, a maximum UTS (107 MPa) and MH (619 HV) were achieved using a welding heat input of 2.34 kJ/cm. Hao et al.10 fabricated the TC4 and SS 304 GTAW joints using single Cu interlayer and Ni-based filler metal. The weld zone cracking was effectively restrained by the Ni-based filler, while Cu interlayer reduced the dissolution of Ti and brittle intermetallic compounds of Ti. Additionally, joining at current of 90 A and with 200 µm thick Cu foil resulted in UTS of 432 MPa and MH of 885 HV. Zhang et al.11 studied the mechanical and microstructural characteristics during two-pass laser welding of titanium TC4 and SS 301 L alloys with vanadium interlayer. The laser beam offset of 0.2 mm on the vanadium interlayer side increased vanadium concentration in the weld zone, resulting in no intermetallic compounds and 599 MPa tensile strength. Chu et al.12 analyzed the effects of vanadium interlayer during GTAW welded bimetallic sheets of TA1 and steel Q325. Severe cracks were found in the joints and fractured from the Fe-Ti rich region, exhibiting microhardness value of 1112 HV. By using V interlayer, average UTS values of 416 MPa and 434 MPa were attained for Fe-Fe and Ti-Ti welded joints respectively. In another study, Wang et al.13 examined how four interlayers—Ag, Ni, V, and Cu—affected the MH and UTS during joining of SS 304 and Ti6Al2Mo2V2Zr alloy. The result indicated that these interlayers prevented intermetallic compound formation and the UTS and MH of the weld portion were 0 MPa and 1005 HV for V filler metal, 124 MPa and 124 HV for Ni, 310 MPa and 204 HV for Ag, and 234 MPa and 80 HV for Cu interlayer respectively. Zhou et al.14 evaluated the content of Nb during the laser welding of Ni-Ti-Nb/Ti-6Al-4 V and result indicated that quantity of intermetallic compounds reduced significantly with the increment of Nb percentage in the welded region, that improve the UTS up to 82% of the inferior base metal Ti-6Al-4 V. From the comprehensive literature review, it has been observed that previous research works mainly focused on the effect of single interlayer material such as Cu, Ag, Ni, V, and Nb on the mechanical characteristics of Ti/SS welded joints. The results of studies proved that single interlayers are still not enough to reduce brittle intermetallic compounds and improve strength.

In recent studies, the authors investigated the effects of composite interlayer/filler metals in dissimilar metal welding to accompany the weld deficiencies occurred in joining with single interlayer. Mannucci et al.15 examined the mechanical attributes of Ti (grade 5) and SS 316 L laser welded joints with Nb and Nb-Cu composite interlayers. The Fe2Nb, and Fe7Nb6 brittle intermetallic compounds were formed using a single Nb interlayer with tensile strength of 160 MPa. Whereas Nb-Cu composite interlayer restricted the foundation of Fe-Nb brittle compounds and resulted in maximum UTS of 255 MPa and MH of 270 HV at Cu/SS interface. Thonondaeng et al.16 evaluated the mechanical performance of SS 304 and Ti-6Al-4 V GTAW welded joints with copper-tin and nickel-copper-based filler metals. The welded joints formed through copper-tin filler showed an under-bead crack due to the forming of a liquation crack. However, no crack was detected with nickel-copper filler. Chu et al.17 investigated the effects of Nb-Cu composite filler during GTAW of titanium and steel plates. The Cu5Nb and Cu30Nb wires exhibited cracks in the weld joints as compared to joints formed by Cu20Nb filler. The Cu5Nb filler with low Nb content produced Cu-Ti compounds, the Cu30Nb wires formed the brittle Fe2Nb compounds due to its higher Nb percentage. The joint welded with Cu20Nb filler showed the Cu solid solution at the weld zone with dispersed Fe2Ti and Fe2Nb compounds. The maximum strength of 334 MPa has been achieved using Cu20Nb filler. Zhang et al.18 examined the performance of titanium TC4 and SS 304 laser welded joints using TA2/Q235 composite interlayer. The Ti-Fe intermetallic was greatly reduced by using composite interlayer. The fracture occurred at the composite interlayer interface region having maximum UTS = 548 MPa and MH = 422 HV. Defeng et al.19 joined titanium TC4 and steel 4J29 with niobium-copper interlayer using laser welding process. A successful suppression of the brittle Fe-Ti was achieved on the Ti side, whereas Cu solid solution formation was promoted on steel side. A maximum UTS of 120 MPa and MH of 640 HV were attained. These studies proved that application of composite interlayers during dissimilar welding Ti and SS reduced the brittle intermetallic and improved the joint’s performance. Paul et al.20 examined the Ta/steel joint behavior in the solid-state welding using Cu interlayer. Results indicated that Cu offers unique features in balancing the heat accumulation and heat dissipation during the welding process. Moreover, it has been indicated that Cu demonstrates zero mutual solubility with the Ta at the solid-state condition due to significant melting temperatures differences and shows partial solubility with the Fe owing to the creation of brittle and hard intermetallic compound such as Ta2Cu3. Yascheritsin and Terletskyi21 performed the theoretical based studies in order to evaluate the volume fractions of Ta and Ni such as 1 to 25% on the UTS of Cu-based composites reinforced with tantalum manufactured through diffusion welding process. The result revealed that optimal UTS of 400 MPa has been attained at the Ta and Ni content ranges between 3 to 7%. These studies highlighted that Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu composite multilayer can improve the mechanical characteristics of Ti/SS welding because single interlayer is still not enough to reduce brittle intermetallic compounds and improve strength.

Literature shows that researchers have investigated the impact of single interlayers including Cu, Nb, Ag, Mg, Ni, and V separately and composite interlayers of Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu on different titanium and stainless-steel alloys grades. However, a comparative evaluation of Ti (grade 6)/SS 304 GTAW welded joints under single Nb, composite multi-interlayers Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu has yet to be explored to enhance the performance of these joints. Therefore, goal of current research is to assess the comparative performance of Ti/SS GTAW joints using single Nb and composite multi-interlayers Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu. Randomized experimental technique was used to design the experiment, and single factor plot analysis is employed to evaluate the effect of selected ranges of process variables (welding current and interlayer type) on the UTS and MH of Ti/SS GTAW joints. The microstructure analysis has been conducted using optical and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) supported by electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) methods while phase analysis is conducted through X-ray diffraction (XRD) method. The mechanical behavior of the joints has been assessed through UTS and MH. This research work substantially assists academic and industrial researchers in the automobile, oil and gas sector, and aerospace to manufacture high-strength and cost-effective Ti/SS joints.

Experimental details

Materials and methods

The stainless steel (304) and titanium grade 6 (Ti-5Al-2.5Sn) plates of 100 mm × 100 mm × 1.5 mm are joined through the GTAW process. It is pretend to mention that interlayer thickness of 100 μm in the GTAW process is widely used and reported value, especially in the research studies of mechanical and microstructural analysis of steel and titanium welded joints22,23,24,25. Hence, Nb and Ta metal foils with a thickness of 100 µm of each have been utilized and Cu filler in the form of wire having a diameter of 1.2 mm has been applied for Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu composite interlayer-based joints. While for single interlayer base joint, Nb in form of foil of thickness 100 µm is used. The Nb and Ta have been placed on the Ti side, whereas Cu is on the SS 304 side as they don’t make intermetallic compounds with each other, as depicted by their binary phase diagrams26. The interlayer thickness of 100 µm is constant parameters for all types of interlayer materials while analysis the evolution of welding current and interlayer types for mechanical and microstructural characteristics of Ti/SS GTAW joints. The chemical composition of SS and Ti has been determined on the base of the optical emission spectrometry test, as illustrated in Table 1. Moreover, pure Nb (99.99%), Cu (99.99%), and Ta (99.99%) have been selected in this experimental study.

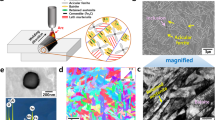

The welding has been performed on a specially designed linear bed, which is motion-controlled by a controller to achieve uniform weld beads, as depicted in Fig. 1. A fine-pointed tungsten electrode of 1.2 mm diameter has been employed to generate a stable electric arc. Argon gas (pure) is used for trailing and bottom shielding of the weld region from the outer environment. The special fixture was designed to clamp the weld plates and shield the welding zone (trailing and bottom). Experiments have been conducted by inserting a single Nb intermediate layer, Ta-Cu, and Nb-Cu composite interlayers. The welding variables such as peak current of 40, background current of 20 A, weld speed of 150 mm/min, pulse frequency of 150 Hz, and gas flow rate of 15 lit/min have been kept the same for these experiments.

The randomized experimental technique was used to design the experiment to examine the impact of welding current and type of interlayers such as Nb, Ta-Cu, and Nb-Cu on the UTS and MH of the SS/Ti GTAW process. The ranges of welding current have been selected on the base of a trial run and literature review27,28,29,30,31, as shown in Table 2. A total of 9 experiments has been designed as a randomized experimental technique to analyze the impact of welding current and type of interlayer on the UTS and MH as demonstrated in Table 3.

Microstructural and mechanical characteristics testing

Specimens have been placed in conductive resin after being cross-sectionally sliced from welded plates for microstructure characterization. The specimen was polished using diamond-pasted micro cloth after being processed through sandpapers with grit levels ranging from 300 to 3000. Prior to welding, the base plates’ and intermediate layers’ connecting edges were reduced and cleaned with acetone. Kroll solution for Ti-5Al-2.5Sn, FeCl3 solution (5 g in water) for copper, Glycerin solution for SS 304, and 20ml H2O + 20ml HNO3 + 10ml HF solution for niobium were used to complete the etching process. 5ml of lactic acid, 5 ml of HF (48%), and 15 ml of HNO3 were used for 120 s in the Ta, Nb, and Nb-Cu etching procedure. Also, 10 ml of HNO3, 10 ml of HF, and 30 ml of H2SO4 were used for five to fifteen seconds. An optical microscope (Olympus) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM: LYRA3, TESCAN) were used to observe the microstructure. Electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) has been used to analyze intermetallic compounds in weld zones and interfaces. According to ASTM standard E8M-0432, the UTS was assessed using a tensile test conducted on tensile specimens with a strain rate of 0.5 mm/min. On the other hand, Vickers indenter has been used to measure the microhardness at the interface region of Ti/SS GTAW joints with load of 50 g and holding time of 15 s according to the ASTM 384-11 standard33. Moreover, three samples at each experimental condition have been selected to measure the microhardness and tensile strength of Ti/SS GTAW joints and mean value for each measurement is considered as final value to ensure the accuracy of results.

Results and disscusion

Microstructural evolution of welded joints

Morphological analysis

The morphological analysis for joints interface with single Nb interlayer, Ta-Cu and Nb-Cu composite interlayers are shown in Fig. 2a–c respectively. Weld configuration with single Nb interlayer (Fig. 2a) consisted of five characteristic zones such as, heat affected zone (HAZ) of Ti, base metal (BM) of Ti, fusion zone (FZ), unmelted Nb, base metal (BM) of SS, HAZ of SS. The coarse grain structure in HAZs and fine equiaxed grain structure in base metals have been observed because HAZ retains high heat near the weld as compared to base metals34. Pronounced cracks were detected at the Nb/SS interface due to limited mutual solubility and brittle Ti–Fe reaction products diffusing through Nb. This weak interfacial bonding explains the poor mechanical behavious of the joint (UTS 173 MPa, hardness 380 HV). Figure 2a depicts that the fusion region lies on both Ti and SS side (separated by dashed lines) under the welded joint at the Nb interlayer type. Although the cracks have been clearly observed at Nb/SS interface but there was comparatively good bonding is achieved at Ti/Nb interface. This was due to good solubility of Ti and Nb and partial soluble of Nb and SS, evidenced by equilibrium diagrams26. Similarly, Fig. 2b depicts the weld configuration with Ta-Cu composite interlayer, it consisted of five zones such as HAZ of Ti, BM of Ti, FZ, unmelted Ta, BM of SS and HAZ of SS. It has been observed the small columnar grain’s structure formed at FZ and expectational fine equiaxed grain structure developed at the HAZ region of base metals with the Ta-Cu composite interlayer-based Ti/SS GTAW joints due to the appropriate mixing of Ta with the base metal at the HAZ that can keep high magnitude of temperature as compared to the base the material. Moreover, grain refinement and defect removal were aided by the Ta dendrites scattered throughout the Cu-rich melt, especially at the Ti/TA interface. Since Cu dissolved easily into SS, the Cu–SS side displayed a broad fusion zone with strong metallurgical bonding. Improved bonding and ductility resulted in the maximum UTS (450 MPa) with relatively low hardness (~ 107 HV) when there were no cracks or voids at either contact. The FZ lies on both Ti and SS side. It has been observed that comparatively thick metallurgical bonding achieved at Cu/SS interface due to good solubility of Cu and SS because there is significantly less melting temperature different (1510 °C − 1083 °C = 417 °C) that causes better penetration and formation of thick and strong metallurgical bonding. Whereas the joint with Nb-Cu composite interlayer (Fig. 2c) clearly indicated that major fusion occurred on SS side. Low melting point copper inserted as a filler wire (high amount of Cu) caused better penetration and strong bonding with steel as well as with Nb whereas a reaction layer (narrow fusion zone) type bond formed at Ti and Nb interface35. Moreover, no obvious cracks are observed on either side of the fusion zone. The microstructure was generally free of cracks and porosity, confirming improved metallurgical compatibility. This balanced morphology correlates with intermediate strength (293 MPa) and low hardness (~ 106 HV), showing improved ductility compared with Nb joints.

SEM and EDS analysis

The formation of various phases at joint interfaces and fusion zones have been analyzed through SEM and EDS analysis. The SEM image for joint with single Nb interlayer has been shown in Fig. 3. At Ti/FZ interface (EDS spot 1 in Fig. 3a, Table 4, the TiNb solution has been formed because Ti and Nb are soluble in each other, which improved the formation of joint at the interface region. However, in FZ of Ti side, the reaction occurred between Fe and Ti to form TiFe brittle intermetallic (spot 2 in Table 4 and EDS graph in Fig. 4 because low melting point of SS as compared to Ti enhances its flow towards Ti side12. Figure 3b shows that some porosities and brittle TiFe2 phases have been found at the fusion zone which reduced the joint strength. In Fig. 3c unmelted Nb (spot 4) have been found owing to the high melting point of Nb, and prominent cracks have been identified which weakened the joint strength at FZ on SS side (Fig. 3c). Hence, a single Nb interlayer also functioned as barrier between SS and Ti but brittle phases of TiFe and TiFe2 are still formed in the fusion area of the joint which caused crack and reduced the mechanical properties.

Figure 5 depicts the 1SEM images of Ti/SS GTAW welded joint fabricated with Ta-Cu composite interlayer. Figure 5a demonstrated that liquid Cu particles melt earlier than Ta due to relatively lower Cu melting point and structure of melted copper solution plunged into Ta matrix. Additionally, weld joint prominently shifts towards the Ti side due to the melting temperature of SS (approximately 1530 °C) is relatively lower than melting temperature of Ti (approximately 1670 °C)10,36, thereby SS melt earlier and diffused into the Ti side of weld joint. So, the diffusion rate of the molten Cu solution that penetrating the Ta matrix into the Ti side of the welded region are relatively larger than SS side of welded region, which turns the development of ductile intermetallic compounds such as Ti3Cu2 and Cu3Ti at the Ti/FZ contact region. Similarly, Fe2Ta intermetallic compound has been created at the SS/FZ interface region due to dynamics of supercooling, which has significant role in the creation of final morphology of solidified melt as depicted in Fig. 5b. It is due to the lack of mutual solubility of Cu and Ta at the whole range of temperatures during welding process, which eliminate voids and strain generation37. Therefore, compact, and high strength metallurgical bonding has been created at the interface region that consists of pure Ta solid dendrites in the Cu melted solutions. Moreover, it has been observed that Ta/Cu composite interlayer can successfully restrict the direct diffusion of SS into steel and formed brittle intermetallic compound at the SS/Ti interface region that reduced the tensile strength and generate crack for the fracture. It is worth noting that holes and cracks has been appeared at the welded region during the direct contact of SS/Ti welding process because the contraction rate of SS was different from the Ti at the FZ state of welding process that linked to different linear expansion coefficient of steel and titanium38,39,40. Thus, Ta/Cu composite interlayer allows to fit the molten pool into the entire molten core after it solidifies that reduces the probability of confined stress and strain generated owing to volumetric shrinkage during the direct contact of SS/Ti and eliminate the large number of cracks and hole generated at the inside the welded joint, as illustrated in Fig. 5c. Hence, ductile, and high strength intermetallic compound has been formed at the chosen areas of the welded interface region of SS/Ti region such as Fe5Ta3 and Ta2Cu as depicted in Table 5 and EDS graph (Fig. 6)). Therefore, it has been determined that Ta-Cu composite interlayer plays a key role to effectively block the direct diffusion of Si into the Ta that eliminates the generation of local stresses and strain generation due to volume shrinkage and enhance the UTS of SS/Ti GTAW welded joint.

The EDS line scan of fusion zone of the Ta–Cu interlayered joint is shown in Fig. 7. Three areas are visible in the profile: the Cu-side fusion zone, the unmelted Ta interlayer, and a SS-side fusion zone. Effective suppression of Fe diffusion into the Ti side is indicated by the steep decline in the Fe signal at the Ta boundary. Concurrently, Cu is evenly dispersed over the interlayer, creating ductile solid solutions that strengthen interfacial bonds. This diffusion profile demonstrates how Ta–Cu stabilizes ductile microstructures while preventing the emergence of Ti–Fe brittle phases.

Figure 8 depicts the SEM images of joint fabricated through Nb-Cu composite interlayer. Figure 8a indicated the major phase at Ti/Nb reaction layer interface (spot 1 in Table 5) is TiNb solution which promote bonding. The FZ of this joint contained Cu solid solution (Cuss) as depicted in Fig. 8b and FeCu solution (spot 3 and 4) which is also proven by EDS graph in Fig. 9 because low melting point Cu dissolves readily in the Nb as well as steel and does not form any brittle phase which ultimately improved the joint strength22. At SS/FZ interface shown in Fig. 8c, FeCu solid solution also depicted in Table 6 has been attained which enhanced the bonding at this side. Thus, Nb-Cu composite interlayer not only prevented the mixing the SS and Ti but also avoid the formation of TiFe and Ti2Fe etc. that are brittle and hard intermetallic compounds and improved the joint strength. Thus, SEM/EDS confirmed that the interlayer composition directly determined the type of IMCs: brittle TiFe/TiFe₂ in Nb joints, ductile Cu-rich solutions in Nb–Cu joints, and a mix of ductile Cu-rich and Ta-containing phases in Ta–Cu joints.

X-ray diffraction analysis

X-ray diffraction analysis has been conducted to identify major intermetallic phases in the fusion zones of the joints and shown in Fig. 10. For single Nb interlayer joint, XRD pattern of fusion zone shows the major peaks of brittle TiFe2 and TiFe compounds which are also confirmed by the results of EDS analysis in Sect. “Mechanical behavior analysis of welded joints” and consistent with findings of previous research41. This is consistent with high hardness (380 HV) and poor tensile performance (173 MPa). The brittle nature of these IMCs restricted plastic deformation, leading to premature interfacial fracture. Figure 10 shows the XRD pattern of fusion zone of welded joint fabricated by using Nb-Cu interlayer. The peaks of graph clearly show the formation of Nb and Cu solid solutions and less brittle TiCu phases and confirmed by previous research17. The suppression of TiFe and TiFe₂ and the presence of ductile Cu-based phases explain the reduced hardness (~ 106 HV) and improved strength (293 MPa). The ductile nature of the weld interface allowed more uniform stress transfer, delaying crack initiation compared to Nb joints. Hence, Nb-Cu interlayer controlled the formation of TiFe brittle phases. Similarly, for joint made by Ta-Cu interlayer (Fig. 10), the XRD pattern confirmed the formation Fe5Ta3 and TiCu phases which are ductile in nature and the formation of brittle phases in the fusion zone is significantly controlled through multi-interlayer and reasonably good joint strength has been attained42. The coexistence of ductile Ta dendrites and Cu-rich solutions with less brittle Ta-based IMCs led to the best mechanical performance i.e., UTS of 450 MPa and moderate hardness (107 HV).

It is observed that the cooling rate in GTAW can have a substantial impact on intermetallic formation and morphology and may permit the temporary creation of non-equilibrium phases. The XRD spectra of the current investigation only showed equilibrium phases, specifically Fe₅Ta₃/Ta₂Cu in Ta–Cu joints, Cu-rich solid solution and TiCu in Nb–Cu joints, and TiFe/TiFe₂ in Nb joints. The absence of additional peaks suggests that although non-equilibrium phases may form during solidification, they are not retained in the final microstructure under these interlayer methods used. This observation confirms that the equilibrium intermetallics, as verified by XRD and SEM/EDS, are the main phases governing mechanical behavior in dissimilar joints.

Mechanism of intermetallic formation

The joint formation mechanism for 3 welded joints has been shown in Fig. 11a–f. Figure 11a shows the molten pool of joint made with single Nb interlayer. As GTAW arc heats the joint, localized melting occurs in the Nb interlayer and may partially melt adjacent regions of Ti-5Al-2.5Sn and SS 304, depending on the heat input. A molten pool forms primarily from Nb, possibly mixed with elements titanium (Ti) and iron (Fe) begin to diffuse toward the molten zone. Nb acts as a physical and chemical barrier and partially melted due to high melting point as discussed in Sect. “Mechanical behavior analysis of welded joints” and slowing direct diffusion between Ti and Fe, thus reducing the risk of forming brittle Ti–Fe intermetallic in the melt. However, at high temperature, Fe from SS may diffuse through the molten Nb and react with Ti, initiating FeTi intermetallic formation within the melt or at the Ti/Nb boundary. As the weld cools, the molten metal pool solidifies as shown in Fig. 11b, beginning at the base metal interfaces and progressing inward. Solidification at the Ti–Nb interface results in the formation of Ti–Nb solid solution or possibly minor TiNb phases—both of which are ductile and structurally stable. At the Nb–SS interface, Fe from SS 304 may have diffused into the molten or partially molten Nb during welding. Upon cooling, these can form intermetallic compounds such as NbFe which are brittle laves phases if present in significant amounts.

Figure 11c depicts the molten pool of joint fabricated through Nb-Cu multi-interlayer. During the molten metal pool stage, Cu melts readily due to its low melting point, forming a liquid layer that wets both Nb and SS 304, while Nb may partially melt or remain in a semi-solid state depending on the heat input. Cu serves as a buffer, absorbing elements like Fe and Ni from SS 304 and preventing their direct diffusion into Ti. Nb acts as a solid-state barrier, reducing the risk of FeTi formation by blocking Fe diffusion from SS 304 to Ti. During solidification of joint as shown in Fig. 11d, the Cu-rich molten zone begins to cool and solidify first at the SS 304 interface, potentially forming ductile Cu–Fe solid solutions or limited intermetallic compounds. The Ti–Nb interface solidifies into a stable Ti–Nb solid solution, while any interaction between Nb and Cu may lead to minimal Nb–Cu phases.

Weld molten for joint made through Ta-Cu multi-interlayer has been shown in Fig. 11e, Cu, having a low melting point, melts first and forms a liquid pool that promotes wetting and bonding between Ta and SS 304. Ta, with its high melting point, typically remains solid or partially melted, acting as a physical and chemical barrier between the Ti and SS 304 sides. This mechanism prevents direct diffusion of Fe into Ti, thus avoiding the formation of brittle FeTi intermetallic compounds. Some limited diffusion of Fe from SS into the Cu melt may occur, possibly forming Cu–Fe phases. During solidification process (Fig. 11f), the Cu-rich molten zone cools and solidifies first, forming ductile Cu-based solid solutions or minor intermetallics near the SS 304 interface. On the Ti side, diffusion bonding occurs at the Ti–Ta interface, typically forming a stable and ductile Ta–Ti solid solution. The resulting joint features a multi-layered structure: a Cu-rich zone at the SS interface, a stable Ti–Ta interface, and a central Cu-Ta diffusion region, all designed to reduce thermal mismatch and suppress brittle intermetallic formation.

Mechanical behavior analysis of welded joints

Ultimate tensile strength

Single factor plot graph has been drawn to evaluate the impact of interlayer type and welding current on the UTS of Ti/SS GTAW welded joints as shown in Fig. 12. It is also found that means values of UTS of GTAW welded joints at Nb is 177.33 MPa, at Ta-Cu is 366.67 MPa and at Nb-Cu is 263.33 MPa as illustrated in Fig. 12. UTS of Ta-Cu interlayer joint has significantly improved than Nb interlayer and Nb-Cu interlayer joints, respectively. It is linked to the mutual solubility of these interlayers at the elevated and high temperature43,44,45. The Ta and Cu are unmixable at lower temperature of welded region due to high melting point and single Nb and multilayer Nb-Cu has high solubility that diffused into the interface region at low temperature of welded region. Therefore, with the change of interlayer type from Nb to Ta-Cu, the mutual solubility of interlayer reduces due to high temperature difference of Nb as compared to Ta and Cu. While Nb completely diffuse into the interface region and formed brittle and hard intermetallic compounds, that is, TiFe2 and TiFe and which have low magnitude of UTS as evident in Fig. 3b and Table 4. On the other hand, Ta-Cu interlayer are partially dissolved into the interface region of welded zone because Ta has relatively higher melt temperature (3020 °C) and Cu has relatively low melt temperature (1085 °C)46. Therefore, only Cu atom completely diffused into the interface region and Ta particles appeared as dispersed phase in the initial phase of Cu melting and then colloidal solution forms that has Ta as solid state form47. Due to this phenomenon, inhomogeneities interface region has been formed at the local melting zone that promotes the adhesion of welded material. As a result, ductile intermetallic compounds have been created at the welded region as depicted in Fig. 5b and Table 5, leading to an increase in the UTS of GTAW welded joints. However, the chances of normal solubility for mixing the atoms of interlayer at the elevated temperature increase with the change of type of multi-interlayer from Ta-Cu to Nb-Cu, that assist the formation of relatively soft solidified melt regions promote the brittle intermetallic phases due to the relatively low melt temperature difference compared to Ta as shown in Fig. 6b and Table 6. It is pretend to mentioned that Nb-Cu interlayer at the welded junction causes brittle intermetallic phases to emerge in the interface region, which encourages the creation of brittle solidified melt regions48. Due to this fact, tensile strength of the welded region reduces. It has been observed that UTS, of welded region, sharply decreases from 300 MPa to 259.67 MPa, with the changing welding current from 30 to 40 A. It is owing to the well-established fact that with the increment of welding current, heat input to the weld region increases that contributed to the generation of inappropriate grain growth, thereby the tensile strength of welded joint reduced49. However, the rate of UTS decreases from 259 MPa to 247.67 with a further decline of welding current in range 40 A to 50 A because the further increment of welding current contributed to the induce the residual stress at the welded region that negatively affects the tensile strength of welded region50. Additionally, excessive welding current is the prime reason for compromise the tensile strength of welded region due the generation of inherent welding defects at the extreme welding current such as incomplete penetration, porosity, inclusions and cracks51. These defect generations have been clear from the SEM analysis of the welded region as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The fracture behavior of Ti/SS GTAW welded joint with the variation of interlayer types has been examined by performing fractography analysis. The SEM images of fracture joint surface of single Nb, composite Ta-Cu and Nb-Cu interlayers are depicted in Fig. 13a–c, respectively. The brittle fracture surface of welded joints with cracks and cavities at single Nb interlayer has been observed due to the inappropriate diffusion of Nb to the interlayer region that allows limited solubility of Nb into the SS and Ti. Hence, cracks and cavities have been detected at the fracture surface of the welded joint as evidence in Fig. 13a. Similar results were also discovered by Shi et al.52 through the joining of dissimilar Ti and SS welded joints. However, the formation of Ti/SS GTAW welded joint with Nb-Cu interlayer formed ductile fractured surface owing to the suitable Nb melting and diffusion of Nb-Cu interlayer at the base metals that allows to develop ductile fracture surface without defect as illustrated in Fig. 13b. It is also attributed to the prominent melting temperature difference between Ta and Cu that promotes the adhesion of welded material because Ta takes higher time to melt as compared to Cu during the fusion process. Substantially, colloidal solutions that solid Ta solutions have been formed that assist to adequately diffuse Nb-Cu interlayer at the interface region and develop GTAW joints with high mechanical strength. It is also pretend to mentioned that ductile facture surface without defects shows the sign of high tensile strength of GTAW welded joints53,54. The Ti/SS GTAW welded joint with the composite Nb-Cu interlayer indicated the formation of ductile fracture surface with small voids as shown in Fig. 13c. The growth of soft intermetallic compounds such as Cuss at the welded region due to relatively low melt temperature difference of Cu as compared to Ta that causes small cracks at the fracture surface17. However, the sizes of avoids have been reduced due to the relatively higher diffusion of interlayers at the base metals of welded joints. So, higher UTS of welded joints at the Nb-Cu interlayer has been attained as compared to the welded joints with Nb interlayer. Hence, the present findings are well justified by the previous relevant research studies that claimed the formation of ductile fracture surface due to the formation of Cuss soft intermetallic compound55.

The stress strain curve for three joints has been presented in Fig. 14. The average ultimate tensile strength (UTS) values obtained from three replications for each joint type. The mean UTS and standard error (SE) has been presented in Table 7. Stress strain curve shows that no ductility whatsoever for joint fabricated through single Nb interlayer and fractured occurred before yield point which reduced the tensile strength of joint (173 MPa). For joint fabricated through Nb-Cu interlayer, a little elongation/strain was observed and joint fractured after the yield point which showed the ductility and imparted the strength of 293 MPa. Moreover, the joint made by Ta-Cu interlayer exhibited high strength of 450 MPa having significant strain or elongation as depicted in Fig. 14. It has been fractured after a necking phenomenon due to high ductility. Hence, the Ta-Cu interlayer joint strength has significantly improved to 61.55% and 34.44% then single Nb and Nb-Cu multi-interlayers respectively.

Microhardness

Single factor plot graph has been drawn to examine the impact of interlayer type and welding current on the microhardness (MH) at the interface region of Ti/SS GTAW welded joints as shown in Fig. 15. It has been observed that MH of welded region sharply increases (101.67 to 118.33 HV) by changing the type of interlayer from type 1(Nb) to type 2 (Ta-Cu). Alternatively, MH of welded joint gradually reduces (to 115.67 HV) with varying interlayer types from type 2 (Ta-Cu) to type 3 (Nb-Cu). Similarly, the single factor plot graph depicted that MH decreases from 118.67 to 113.67 HV by changing weld current from 30 to 40 A and reduces further to 103.33 HV with the increment of welding current up to 50 A as shown in Fig. 15. It is owing to the fact that Nb has high mutual solubility due to low melt temperature that promotes the high interpenetration of welded metals at the interface region and form soft and ductile intermetallic compounds56,57,58. It is also linked with the solubility rate of Cu into the SS side that is relatively higher than the Ti with Ta during the formation of welded joint due to the prominent melting temperature difference between Ta and Cu. Therefore, Cuss compound formed at the interface region of welded region at Nb-Cu interlayer that imparted softness and reduced the microhardness at the welded joint, as illustrated in Fig. 5 and Table 5. Thus, relatively low magnitude of MH has been attained at the welded region. While, Ta-Cu has zero solubility at the ambient temperature and partial solubility at the higher temperature that avoid the interpenetration of welded metals that promote the dispersion-hardened phenomena at the interface region of welded zone59,60. Therefore, brittle and hard intermetallic compounds such as Ti3Cu2 and Fe2Ta have been formed that have relatively higher magnitude of MH of welded region as proven from the SEM analysis at Fig. 6 and EDS Table 6.

The distribution of microhardness along the cross section of the Ti/SS GTAW welded joints has been studied to further demonstrate the effect of type of interlayers such as Nb, Nb-Cu, and Ta-Cu interlayer as shown in Fig. 16. The microhardness has been measured on cross section of the weld samples from Ti to steel side having distance of 0.1 mm between each indent. Average values of MH of BM Ti and SS are 320 and 142 HV correspondingly. Average values of MH of HAZs of both BM have been increased (Ti = 350 HV and SS = 173 HV) due high heat content in this region in case of all joints. The low MH of 66 HV (average) for unmelted Nb has been observed in the case of all joints because of its ductile nature. However, high microhardness of 380 HV has been observed in the fusion zone for joint with single interlayer due to formation brittle TiFe compounds. Therefore, the tensile strength of these joints became low (173 MPa). Pasang et al.61 also found high microhardness at the fusion zone of Ti/SS GTAW joints owing to the creation of these intermetallic phases which dropped the joint strength. The MH of fusion zone of joint with Nb-Cu composite interlayer become low (106 HV) due to the formation of Cu solid solution (Cuss) also depicted in SEM Fig. 6b and EDS Table 6. The formation of Cuss imparted softness and ductility and enhanced the joint’s strength. The exceptional UTS for this joint has been attained of 293 MPa. Hao et al.62 attained better strength at low microhardness ∼ 100 HV owing to Cuss formation during GTAW of titanium TC4 and SS. Therefore, a significant improvement in mechanical properties of dissimilar Ti-SS GTAW welded joints have been attained using composite Nb-Cu interlayer joining technique.

However, brittle and hard intermetallic compounds such as Ti3Cu2 and Fe2Ta has been created at the Ti and SS side of FZ of welded region that has MH of 360.60 HV and 184.83 HV. It is worthily mentioned that creation of brittle and hard intermetallic compounds (IMC) at the fusion zone of Ni interlayer-based Ti/SS welded joint increase microhardness due to the local stress concentrations that reduces the UTS of joint of welded joint63. Conversely, solubility of Cu into the SS side is comparatively higher than the Ti with Ta during the formation of welded joint at the HAZ due to the significant high melting temperature difference between Ta and Cu that develop Cu enrich solidified solution with solid Ta dendrites that develop soft and ductile intermetallic compounds such as Fe5Ta3 and Ta2Cu as illustrated in EDS Table 6. This softness of intermetallic compounds imparted the formation of extremely high UTS of SS/Ti welded joints with the Ta-Cu interlayer. Ultimately, MH of 162.2 HV has been attained at the SS side of welded joint and 186.12 HV at the Ta side of welded joint at the HAZ region. Thus, the expected high tensile strength of 450 MPa has been attained due to the ductile nature of welded joints. Similarly, study of Yu et al.25 concluded that microhardness of Ti/SS welded joint with the addition of Cu interlayer decreases due to the formation of soft intermetallic compound with Ti-Cu and relatively high microhardness at the Ti-Fe side of welded region due the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds such as FeTi that eliminate the internal stresses of welded joint with Cu interlayer which increases the tensile strength of welded joint.

Improvement in ultimate tensile strength

The comparative analysis of tensile strength for Ta-Cu interlayers with other interlayers used in the various welding process at optimal experimental conditions has been conducted to signify the importance of proposed novel interlayers for the mechanical characteristics of welding processes as shown in Table 8. According to the comparison analysis, with using Ta-Cu interlayer, UTS has been improved by 27.33% in comparison with Nb/Cu interlayer-based Ti/SS GTAW joints22. Moreover, the comparative analysis of Ti/SS GTAW welding process with the proposed Ta-Cu interlayer-based Ti/SS GTAW joint depicted that 44.89% UTS of Ti/SS GTAW welded joint improved by using Ta-Cu interlayer in the Ti/SS GTAW welding process64. The comparison of laser welding of Mg interlayer-based Ti–6Al–4 V/ AISI 304L with the Ta-Cu interlayer-based Ti/SS GTAW welded joint demonstrated the improvement up to 50.89% with replacing Mg interlayer with Ta-Cu interlayer65. In comparison with another study of joining CpTi/Ta/SS 304 joints using Laser beam welding (LBW), the UTS of current study has been improved to 91.11%66. The UTS obtained in this study has been enhanced to 36.89% compared with pure Ti and SS 304 joints by placing Ag interlayer through LBW67. The Ti-2.5Sn-5Al/Ta/Cu/SS 304 joint strength in current study has been improved to 29.11% when comparison with the TC4/Cu/SS 304 joints fabricated by MIG-TIG hybrid welding68. Therefore, it has been determined that proposed novel Ta-Cu interlayer has substantial enhancements of tensile strength of GTAW process especially for the Ti/SS joints. Moreover, Ti alloys are widely used for aviation and aerospace applications due to high specific strength, high corrosion resistance and other mechanical properties at elevated temperatures. Stainless steel has high density than Ti alloys and applicable in the automotive industry to manufacture lightweight parts at relatively low cost69. The proposed research work significantly improved the mechanical characteristics of Ti/SS GTAW application by reducing weight and cost at same time without compromising mechanical characteristics that allows to use these Ti/SS joints in joining discs with engine blades at the aviation sectors and oil rig components and cryogenic piping in the oil and gas industrial sector.

Conclusions

This research explored the interfacial microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of stainless steel 304 and Grade 6 Ti alloy GTAW joints by applying a single Nb interlayer, composite Nb-Cu, and novel Ta-Cu interlayers. The following conclusions have been drawn.

-

A single factor plot analysis determined that the UTS of the welded region sharply increases by changing the type of interlayer from Nb to Ta-Cu and gradually reduces from Ta-Cu to Nb-Cu. Whereas, MH of the welded region sharply increases by changing the type of interlayer from Nb to Ta-Cu and decreases with varying the interlayer type from Ta-Cu to Nb-Cu.

-

Microstructure analysis revealed that prominent cracks have been observed in the FZ of the Nb/SS side in the joint with a single Nb interlayer. Brittle phases such as TiFe and TiFe2 are also observed through SEM and EDS analysis, which reduced the joint strength. Whereas no such brittle phases have been observed in joints welded through the composite Nb-Cu and Ta-Cu interlayers techniques.

-

The microhardness of FZ of the joint with a single interlayer has increased to 380 HV, which caused brittleness and reduced the tensile strength of 173 MPa. In the case of the application of composite Nb-Cu interlayer, the low microhardness of 106 HV was attained in the FZ, as depicted by the formation of Cuss. However, soft and ductile nature intermetallic compounds (Fe5Ta3 and Ta2Cu) have been formed at the Ta-Cu interlayer-based SS/Ti GTAW joint owing to the creation of Cu enriched solidified melted solution with contains Ta dendrites.

-

The application of Ta-Cu interlayer at the welded region assists to achieve the UTS of 450 MPa. It has been observed that replacing single Nb (173 MPa) and Nb-Cu (295 MPa) interlayers with the Ta-Cu composite interlayer significantly improved the UTS of 61.55% and 34.44%, respectively. Moreover, the appropriate filling of the molten pool into the molten core with the Ta-Cu interlayer avoids generating local stress; consequently, it eliminates many cracks and holes generated at the welded region.

-

Fractography analysis concluded that ductile fracture surface without defect has been attained at the Ta-Cu interlayer due to the suitable melting of Cu and Ta at the welded region. However, brittle fracture surface surfaces have been observed with single Nb interlayer and ductile fracture surface with small voids have been achieved with Nb-Cu interlayer.

The research is limited to applying Nb, Ta-Cu, and Nb-Cu interlayers effects on the mechanical characteristics and microstructural behavior of Ti/SS GTAW welded joints. Research work is beneficial for manufacturing pressure vessels, heat exchangers, and other critical chemical, oil, and gas components. However, quantitative defect analysis (porosity percentage, crack length density), detailed grain size or phase fraction measurements, and interlayer thickness optimization need to explore more in depth, therefore recommended for future work. Moreover, long-term performance under fatigue, creep, and corrosion should also be evaluated to confirm industrial applicability.

Data availability

The data relating to experimental findings is already reported within the paper, and it can also be available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

References

Tang, H. et al. Test and theoretical investigations on flexural behavior of high-performance H-shaped steel beam with local corrosion in pure bending zone. Steel Res. Int. 96 (7), 2400640. https://doi.org/10.1002/srin.202400640 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Experimental investigation of fatigue behavior and fracture mechanisms in welded joints of 321 stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 45, 112193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.112193 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Design strategies for enhancing strength and toughness in ultrasonic welding of dissimilar metals: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 42, 111502 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Effect of electrical pulse treatment on the microstructural and mechanical responses of heterogeneous linear friction welded TC17/TC4 dissimilar joint. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 35, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2025.01.011 (2025).

Tomashchuk, I. & Sallamand, P. Metallurgical strategies for the joining of titanium alloys with steels. Adv. Eng. Mat. 20(6), 1700764 (2018).

Chengyu, H. et al. Investigation on microstructure and properties of the local dry underwater TIG welding of 304 L stainless steel. Mater. Today Commun. 44, 111978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.111978 (2025).

Yuan, J. et al. Synergizing TWIP and TRIP effects for optimized mechanical performance via stacking fault energy control in austenitic steels. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 25 (5), 277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-025-01333-0 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. A hybrid joint based on two kinds of bonding mechanisms for titanium alloy and stainless steel by pulsed laser welding. Mater. Lett. 185, 152–155 (2016).

Zhao, W. et al. Experimental study on chip deformation of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy in cryogenic cutting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 96(9), 4021–4027 (2018).

Hao, X. et al. Arc welding of titanium alloy to stainless steel with Cu foil as interlayer and Ni-based alloy as filler metal. J. Market. Res. 13, 48–60 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Microstructure and mechanical property improvement of dissimilar metal joints for TC4 Ti alloy to 301L stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 2942–2955 (2018).

Chu, Q. et al. Influence of vanadium filler on the properties of titanium and steel TIG welded joints. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 240, 293–304 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Microstructures and mechanical properties of electron beam-welded titanium-steel joints with vanadium, nickel, copper and silver filler metals. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 23, 1498–1504 (2014).

Zhou, X. et al. Effects of niobium addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of laser-welded joints of NiTiNb and Ti6Al4V alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 735, 2616–2624 (2018).

Mannucci, A. et al. Use of pure vanadium and niobium/copper inserts for laser welding of titanium to stainless steel. J. Adv. Join. Process. 1, 100022 (2020).

Thonondaeng, T., Fakpan, K. & Eidhed. K. Dissimilar metals welding of CP titanium to 304 stainless steel using GTAW process. In: Applied Mechanics and Materials. Trans Tech Publ. (2016).

Chu, Q. et al. The formation of intermetallics in Ti/steel dissimilar joints welded by Cu-Nb composite filler. J. Alloy. Compd. 828, 154389 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Microstructure and mechanical property improvement of dissimilar metal joints for tc4 ti alloy to 304 stainless steel using ta2/q235 composite interlayer. Met. Mater. Int. 27, 1224–1235 (2021).

Mo, D. et al. Influence of welding speed on the microstructure and mechanical properties of electron beam-welded joints of TC4 and 4J29 sheets using Cu/Nb multi-interlayers. Metals 8(10), 810 (2018).

Paul, H. et al. Interfacial reactions and microstructure related properties of explosively welded tantalum and steel sheets with copper interlayer. Mater. Des. 208, 109873 (2021).

Yascheritsin, E. & Terletskyi. O. The influence of structure on mechanical properties of multilayered Cu–Ta composites at room temperature. In: International Conference on Reliable Systems Engineering. Springer. (2023).

Jawad, M., Jahanzaib, M. & Ilyas, M. Evaluation of welded joints of dissimilar titanium alloy Ti-5Al-2.5 Sn and stainless-steel 304 at different multi-interlayer modes. Mater. Res. Express 9(10), 106501 (2022).

Pan, Y. et al. Effect of Ni interlayer thickness on the welding morphology and mechanical properties of SPS diffusion-welded YG8/40Cr joints. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 33(14), 7008–7019 (2024).

Fande, A. et al. Influence of inconel interlayer on microstructural, mechanical and electrochemical characteristics in single-pass ATIG welding of dissimilar austenitic and duplex stainless steel. Mater. Res. Express 11(5), 056519 (2024).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, C. Effects of interlayer on the microstructure and mechanical properties of resistance spot welded titanium/steel joints: A short review. Metals 14(4), 429 (2024).

Notis, R., et al., ASM Handbook Volume 3 Alloys Phase Diagrams. ASM International. 841–869. (1992).

Singh, C., Kumar, H. & Kumar, R. Measurement and analysis on the sensitization behavior of SS-304 welds using Nb-based stabilization through flux-coated gas tungsten arc welding. Meas. Control 52(7–8), 879–887 (2019).

Li, Y., Martín, D. S., Wang, J., Wang, C. & Xu, W. A review of the thermal stability of metastable austenite in steels: Martensite formation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 91, 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.03.020 (2021).

Shehbaz, T. et al. Dissimilar tungsten inert gas welding between Inconel 718 and commercially pure titanium using a vanadium interlayer. In: Proc. of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications. 236(4), 715-729. (2022).

Huang, M. et al. Optimizing crack initiation energy in austenitic steel via controlled martensitic transformation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 198, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2024.02.019 (2024).

Ali, H. et al. Evaluation of the process parameters on the microstructure and mechanical properties of cladded SA516 GR70 steel welded joints. Tech. J. Univ. Eng. Technol. Taxila. 29 (3), 2313–7770 (2024).

Highway, A.A.S. and T. Officials, Materials, E8M-04 Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials (Metric) 1. ASTM Int. (2004).

Standard, A., e384, Standard Test Method for Knoop and Vickers Hardness of Materials. West Conshohocken, USA: ASTM International. (2011).

Junaid, M., et al., Microstructure, mechanical properties and residual stress distribution in pulsed tungsten inert gas welding of Ti–5Al–2.5 Sn alloy. In: Proc. of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications. 233(10), 2030–2044. (2019).

Wang, X., Sun, D. & Sun, Y. Influence of Cu-interlayer thickness on microstructures and mechanical properties of MIG-welded Mg-steel joints. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 25(3), 910–920 (2016).

Wiegand, M., et al. Dissimilar Laser Beam Welding of Titanium to Stainless Steel Using Pure Niobium as Filler Material in Lap Joint Configuration. In Photonics. MDPI. (2023)

Feldman, B. & Dunham, S. T. Calculation of Cu/Ta interface electron transmission and effect on conductivity in nanoscale interconnect technology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95 (22), 222101 (2009).

Zou, Y., Tang, S., Guo, S. & Song, X. Tool wear analysis in turning inconel-657 using various tool materials. Mater. Manuf. Process. 39 (10), 1363–1368. https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2024.2323434 (2024).

Mansor, M. S. M. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of micro-resistance spot welding between stainless steel 316L and Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 96, 2567–2581 (2018).

Jawad, M. et al. Evaluation of residual stresses and distortion of Ti-5Al-2.5 Sn and SS 304 gas tungsten arc welded joints under hybrid thermal tensioning technique: Transient thermal tensioning and trailing intensive cooling. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 33, 7564–7576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-024-09363-0 (2024).

Cai, G., Huang, Y., Qing, Y., & Misra, R. D. K. Effects of Y and Hf addition on soft magnetic property and ductility improvement of Fe–6.9 wt% Si alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 37, 1362–1378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2025.06.098 (2025).

Pugacheva, N. B. et al. Study of the chemical composition and microstructure of AISI 321/Cu/Ta/Ti welded joint. Phys. Met. Metall. 121 (11), 1112–1118 (2020).

Kumar, M. B. et al. Influence of pulsed current GTAW-WAAM process parameters on the single layer bead geometry and multi bead multi-layer deposition of a nickel-based superalloy. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 108824 (2024).

Lei, Y., Xiong, J. & Li, R. Effect of inter layer idle time on thermal behavior for multi-layer single-pass thin-walled parts in GMAW-based additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 96, 1355–1365 (2018).

Hanif, M. W. et al. Evaluating the influence of copper bar preheating temperature on the electromechanical and microstructural characteristics of in situ heat-treated 7075Al/Cu composite joints. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 34, 17214–17234 (2025).

Meng, X. et al. Effect of the thickness of Cu interlayer on dissimilar laser welding of 304 stainless steel to tantalum. Opt. Laser Technol. 157, 108727 (2023).

Greenberg, B. et al. The problem of intermixing of metals possessing no mutual solubility upon explosion welding (Cu–Ta, Fe–Ag, Al–Ta). Mater. Charact. 75, 51–62 (2013).

Grinberg, B. et al. Peculiarities of formation of structure in the transition zone of the Cu-Ta joint made by explosion welding. Paton Weld. J. 7, 20–25 (2011).

Sujith, K. S. & Ravi, S. Assessment of corrosion and macrostructural behavior of Ti6321/SS 310 butt joints: In situ study of similar and dissimilar joints via friction stir welding technique. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 34, 18620–18633 (2025).

Hamed Zargari, H., Zand, S. & Rezayat, M. Dissimilar laser welding of Ti-CP4 to MP35N medium-entropy bio-alloy. Weld. World. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-025-01966-y (2025).

Jia, L. et al. Interplay between H atoms and characteristic microstructure features in 2100 MPa grade full pearlite steel wire for bridge cable. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 172, 151226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.151226 (2025).

Shi, Z. et al. Enhanced strength of laser welded steel/titanium butt joints with vanadium multi-layers and a copper plate as a composite intermediate layer. Opt. Laser Technol. 180, 111478 (2025).

Kumar, S. et al. Evolution of surface morphology and mechanical characterization of GTAW welded SDSS thin sheets. Results Surf. Interfaces 18, 100412 (2025).

Mofid, M. A., Nasiri Vatan, H. & Haj Kazemian, M. R. Evaluation of microstructure, corrosion resistance performance, and mechanical properties of 316L austenitic stainless steel FCAW welded joints: a comparative study. Can. Metall. Q. 64(1), 77–88 (2025).

Gao, X.-L. et al. Laser welding of Ti6Al4V to Cu using a niobium interlayer. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 270, 293–305 (2019).

Vinoth Kumar, D., Gejendhiran, S. & Karpagaraj, A. Dissimilar welding of nickel-based Superalloy—A review. Adv. Sci. Technol. 130, 3–11 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A study on microstructure and mechanical properties of electron beam welded joint of Nb/selective laser-melted TC4 dissimilar alloys. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 34, 9868–9877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-024-09865-x (2025).

Hanif, M. W. et al. Evaluation of microstructure and mechanical properties of squeeze overcast Al7075− Cu composite joints. China Foundry 20(1), 29–39 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Ultra-high temperature oxidation resistance of a MoSi2 composite coating with TaB2 diffusion barrier on tantalum alloy. Corros. Sci. 224, 111563 (2023).

Pushkin, M. et al. Microstructure of joints Cu–Ta, Cu–Ti, Cu–Cu, produced by means of explosive welding: fractal description of interface relief. Compos. Interfaces 28(1), 63–76 (2021).

Pasang, T. et al. Characterisation of intermetallic phases in fusion welded commercially pure titanium and stainless steel 304. Metals 8(11), 863 (2018).

Hao, X. et al. Dissimilar joining of TC4 alloy to ST16 steel by GTAW. J. Manuf. Proc. 37, 413–417 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Influence of interlayer Nb on the performance of joint between titanium and steel welded by resistance spot welding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 31, 1–8 (2021).

Ali, A., Jahanzaib, M. & Jawad, M. Performance evaluation of Ti and SS dissimilar GTAW joints via non-destructive testing methods. Eng. Proc. 75 (1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024075036 (2024).

Gao, M. et al. Characterisation of laser welded dissimilar Ti/steel joint using Mg interlayer. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 17(4), 269–276 (2012).

Shanmugarajan, B. & Padmanabham, G. Fusion welding studies using laser on Ti–SS dissimilar combination. Opt. Lasers Eng. 50(11), 1621–1627 (2012).

Zhang, Y. et al. Butt laser welding of TC4 Titanium alloy and 304 stainless steel with Ag-base filler metal based on a hybrid connection mechanism. Opt. Laser Technol. 124, 105957 (2020).

Cheng, Z. et al. Interfacial microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of TC4 alloy/304 stainless steel joints with different joining modes. J. Manuf. Process. 36, 115–125 (2018).

Kusy, R. P. & Whitley, J. Q. Thermal and mechanical characteristics of stainless steel, titanium-molybdenum, and nickel-titanium archwires. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 131(2), 229–237 (2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M. Jawad, M. Jahanzaib; Methodology, M. Jawad and M.A. Ali; Software, M. Jawad, M.W. Hanif and M.A. Ali; Validation, M. Jawad; Formal analysis, M. Jawad and M.W. Hanif; Investigation, M. Jawad, M.A. Ali and M.W. Hanif; Data curation, M. Jawad; Writing—original draft preparation, M. Jawad, M.A. Ali and M.W. Hanif; Writing—review and editing, M. Jawad, M.A. Ali, M. Jahanzaib, and T.C. Jen, A.A. Adediran; Visualization, M. Jawad, and M.A. Ali; Funding acquisition, T.C. Jen, A.A. Adediran; Supervision, M. Jahanzaib. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed upon the current version of the submission for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jawad, M., Hanif, M.W., Ali, M.A. et al. Comparative evaluation of Nb, Nb-Cu, and Ta-Cu interlayers on microstructural and mechanical behavior of dissimilar welds of grade 6 Ti and stainless steel. Sci Rep 15, 41949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25882-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25882-9