Abstract

To address the challenge of suppressing low-frequency vibrations in offshore wind turbine towers under complex environmental loads, this paper innovatively proposes a pendulum-tuned particle damper (PTPD). This design combines the high space utilization efficiency of pendulum structures with the broadband energy dissipation advantages of particle damping. A four-degree-of-freedom coupled tower-PTPD model and its Lagrangian equations of motion were established. Using the Finite Element-Discrete Element (FEM-DEM) coupling method, the effects of pendulum length and particle diameter on vibration suppression performance were systematically studied under three wind load conditions. Simulation results show that under Condition 1, a PTPD with a 3.50 m pendulum length filled with 200 mm iron-based particles achieves a peak vibration reduction rate of 58.1%, significantly reducing the tower’s vibration acceleration amplitude. A 1:65 scaled model was designed and tested, demonstrating that a combination of 625 mm pendulum length and 10 mm particles achieved a 58.0% vibration reduction rate. This validates the parameter optimization principles derived from simulations and provides an effective solution for anti-fatigue design of offshore wind turbines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Offshore wind energy plays a pivotal role in developing clean energy along China’s coast1. Its advancement helps optimize coastal energy structures and supports the national “Dual Carbon” strategic goals2. With policy support, the industry is rapidly expanding. During the 14th Five-Year Plan period, China’s new offshore wind installations are projected to reach approximately 40 GW, making it the world’s largest offshore wind market3. Compared to onshore environments, offshore conditions (strong winds, huge waves, sea ice, ocean currents) are more severe, with wind loads being the primary factor affecting turbine safety4,5. As the core load-bearing structure, the support tower must ensure stable operation of the upper rotor system while accommodating surging loads from increasingly large-scale turbines, demanding higher reliability, safety, and cost-effectiveness6,7,8.

Currently, most offshore wind facilities are deployed in shallow waters (< 60 m depth) using fixed support structures. Monopile foundations dominate the market (> 70% global share in 2022) due to their simplicity and ease of installation9,10,11. However, towers inherently exhibit low damping and slow vibration decay, which can cause structural damage. Consequently, various vibration suppression devices have been developed worldwide to extend service life. Wang et al.12 investigated a pendulum eddy current damper (ECD) through theoretical analysis and model tests, focusing on magnetic attraction and permanent magnet arrangement effects on frequency and equivalent damping. Le et al.13 developed a Tuned Liquid Damper (TLD) for a 1:15 scale 6.45 MW offshore wind turbine model. Shake table tests showed 50% average acceleration reduction under sinusoidal excitation and > 40% standard deviation reduction under seismic loads. Carswell et al.14 utilized a Tuned Liquid Column Damper (TLCD) to control monopile turbine vibrations under wind-wave loads. Numerical simulations confirmed effective response reduction and fatigue life extension. Sun et al.15 developed a 3D-Pendulum Tuned Mass Damper (3D-PTMD) suppressing multidirectional tower-nacelle vibrations simultaneously, extending fatigue life by 50% for a monopile 5 MW turbine under combined loads. Liu et al.16 applied a pendulum-type tuned mass damper (TMD) to wind turbine towers to mitigate wind-induced vibrations, thereby reducing the risk of generator failures and structural damage. They systematically investigated the effects of mass ratio, damping ratio, and natural frequency ratio of the pendulum TMD on vibration suppression and energy dissipation. Le et al.17 examined the dynamic response of a monopile-supported wind turbine under combined wind and wave loads. The multiple tuned mass dampers (MTMDs) they designed demonstrated greater robustness compared to a single TMD, reducing the standard deviations of tower-top acceleration and displacement by over 50% and effectively suppressing the spectral response at the fundamental frequency. Dong et al.18 developed a C-shaped particle damping tuned mass damper (C-type PD-TMD). Using a dual-particle model and particle swarm optimization for parameter design, they validated its superior performance over conventional TMDs under large displacements and various excitations, demonstrating broader damping bandwidth and enhanced robustness. Lu et al.19 conducted a comparative study between TMD and tuned particle dampers (PTMD) using a five-story steel frame structure. The results showed that both devices significantly reduced structural displacement and acceleration responses when properly tuned, with the PTMD exhibiting better performance, wider frequency bandwidth, and improved robustness. Subsequent free and forced vibration tests on wind turbine assemblies confirmed that the PTMD effectively suppressed dynamic responses at the tower top and internodes, outperforming the TMD20. Chen et al.21 performed shake table tests on a scaled wind turbine tower model with and without a tuned rolling ball damper (TRBD) under overspeed, gust, and blade flutter conditions. They found that the rolling balls inside the spherical container, capable of moving in any direction, significantly increased the structural damping of the tower. This led to rapid attenuation of dynamic responses and improved fatigue life. The TRBD provided effective vibration reduction across all tested operational conditions. Nevertheless, conventional Tuned Mass Dampers (TMDs) struggle to effectively suppress low-frequency vibrations in offshore towers under complex conditions due to their narrow bandwidth and limited adaptability22.

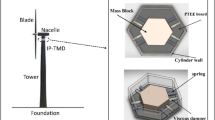

Facing increasingly demanding operating conditions, high-performance dampers are urgently needed to enhance structural durability and reliability. Integrating the pendulum damper’s high space utilization and multidirectional tuning capability23,24,25 with particle dampers’ strong stability, wide adaptability, and high robustness26,27,28,29, this paper innovatively proposes a Pendulum-Tuned Particle Damper (PTPD), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Tower-PTPD system modeling

Simplified model of the tower-PTPD system

Offshore wind turbine towers continuously endure dynamic alternating loads from wind and waves during operation. The resulting cyclic stress is a key factor inducing structural fatigue damage. With inherently weak damping characteristics, the towers struggle to rapidly dissipate vibrations caused by external excitation, accelerating fatigue accumulation. Installing PTPDs in high-vibration zones effectively reduces vibration amplitudes, thereby enhancing structural fatigue resistance.

This study focuses on monopile-foundation offshore wind turbine towers, establishing a simplified mathematical model (Fig. 2). Ignoring the discrete nature of granular materials, the tower’s vibration under external loads is simplified as a two-degree-of-freedom forced vibration system, with u(t) and v(t)19. The PTPD is modeled as a two-degree-of-freedom pendulum system, with \(\theta (t)\) and \(\varphi (t)\).

Lagrangian-based system equations of motion

The Lagrangian equations for the tower-damper system under forced vibration (without particles) are:

Where \({q_r}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} u&v&\theta &\varphi \end{array}} \right]\) represents the generalized coordinates, \({\dot {q}_r}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\dot {u}}&{\dot {v}}&{\dot {\theta }}&{\dot {\varphi }} \end{array}} \right]\) denotes the generalized velocities, \({{\mathbf{Q}}_{\mathbf{r}}}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{F_u}(t)}&{{F_v}(t)}&0&0 \end{array}} \right]\) is the generalized force, while T, V and F represent the system’s kinetic energy, potential energy, and dissipation functions, respectively.

A horizontal linear spring and a linear viscous damper are incorporated between mass m and the tower at the same height. The position of the damper s is defined by five parameters: planar angle \(\theta\), spherical angle \(\varphi\), pendulum length l, primary system displacement u and v. The position sx, sy, sz of the damper and the displacement increments rx, ry, rz at both ends of a horizontal linear spring and a linear viscous damper in the x, y, z directions are:

For the damper subsystem, the kinetic energy \({T_m}\), gravitational potential energy \({V_g}\), elastic potential energy \({V_k}\), and dissipation function \({F_c}\) are:

Where g is gravitational acceleration; \({r_x}=lsin\theta cos\varphi\), \({r_y}=lsin\theta \sin \varphi\), \({r_z}=l(1 - cos\theta )\) are spring elongations in the x, y and z directions; and \({c_x}\), \({c_y}\), \({c_z}\) are the damping coefficients of linear viscous dampers in the x, y and z directions.

For the tower subsystem, the kinetic energy \({T_M}\), potential energy \({V_M}\), and dissipation function \({F_M}\) are:

Where \(\left[ M \right]\) is the mass matrix, \(\left[ K \right]\) is the stiffness matrix, \(\left[ {\text{C}} \right]\) is the damping matrix, \({\mathbf{V}}\) is the velocity vector, and \({\mathbf{S}}\) is the displacement vector.

Substituting Eqs. (2)–(8) into Eq. (1) yields the system of motion equations for the 4-DOF tower-damper model:

FEM-DEM coupled simulation

In simulations, the granular material filling the damper cavity is a discontinuous medium. Its damping effect cannot be directly modeled via the finite element method by constructing a damping matrix coupled with the tower-PTPD motion equations. Therefore, the coupled Finite Element-Discrete Element (FEM-DEM) method was employed to analyze particle interactions. The damper walls were discretized into triangular shell elements (S4R), accurately capturing complex geometric boundaries while ensuring efficient contact search (Fig. 3). Each element typically experiences forces from multiple particles. Contact forces exerted by particles on shell elements were transferred to element nodes using the shape function method, thereby enabling effective FEM-DEM coupling.

The relationship between the element local coordinate system and the global coordinate system is:

Where \(\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mathbf{T}}_{t,1}}} \end{array}} \right]\) denotes the transformation matrix from the global to the local coordinate system, \(\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mathbf{T}}_{{\text{t}},{\text{1}}}}} \end{array}} \right]={\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\{ {{\text{n}}_{\text{x}}}\} \{ {{\text{n}}_{\text{y}}}\} \{ {{\text{n}}_{\text{z}}}\} } \end{array}} \right]^{\text{T}}}\). The transformation matrix for converting contact forces and moment vectors from the local to the global coordinate system is:

The transformation matrix for converting forces and moments at the three nodes of the triangular element from the local to the global coordinate system is:

Thus, the contact forces at each node in the global coordinate system are:

Where \({{\mathbf{N}}_{\text{a}}}\) is the interpolation matrix of the contacted element a, M is the number of particle contact points on the triangular element, and Wc, a is the force/moment vector exerted by particles at the contact point. Using these equations, forces and moments from particles on the shell element are converted into nodal forces. This further allows the determination of the damping force exerted by particles on the pendulum motion.

Multi-parameter vibration reduction performance simulation

Wind loads on the turbine

According to Reference19, the wind speed distribution in offshore wind farms in southeastern China predominantly ranges from 0 to 20 m/s30. Given that the rated wind speed of the studied wind turbine is 12 m/s, three representative mean wind speeds were selected: the rated speed of 12 m/s, a high wind speed of 20 m/s, and an intermediate value of 16 m/s. Sea surface wind speed comprises mean and fluctuating components. Referring to the operational conditions of the turbine prototype, the Kaimal wind spectrum was adopted to generate wind speed time-history curves with mean velocities of 12 m/s (Condition 1), 16 m/s (Condition 2), and 20 m/s (Condition 3) (Fig. 4). The wind power spectral density function is:

Where c is the Monin coordinate, f is frequency, h is the height for wind load calculation, and \({u_*}\) is the friction velocity.

PTPD vibration suppression analysis

The simulation referenced an 8 MW offshore wind turbine. Based on a simplified method19, parameters for the tower’s two-degree-of-freedom system were determined: mass M = 512.2 tonnes, equivalent stiffness k = 1,819,879.1 N/m, and equivalent damping coefficient c = 12,541.3 N·s/m.

To analyze the effects of pendulum length and iron-based particle diameter on PTPD performance under three wind conditions while reducing computational cost and controlling variables, the tower was modeled as the simplified two-degree-of-freedom system in Fig. 2. The PTPD casing was discretized using S4R shell elements, while internal particles were modeled as PD3D elements. All particles were assumed homogeneous with six degrees of freedom (translation and rotation). Particle-particle and particle-wall interactions followed Hertzian contact theory.

Varying the PTPD pendulum length l alters its stiffness k and mass m, thereby shifting the natural frequency \({\omega _a}\). To facilitate parametric analysis, two PTPD groups with pendulum lengths of 3.0 m and 3.5 m were tuned to the same natural frequency (0.298 Hz) using Eqs. (15)–(16). The parameters of PTPD1 and PTPD2 are shown in Table 1.

Where \({f_{opt}}\) is the optimal frequency ratio, \({\omega _n}\) is the undamped natural frequency of the primary system, and \(\mu\) is the mass ratio \((\mu =\frac{{\text{m}}}{{\text{M}}})\).

Particle diameter variations maintained constant total particle weight.The total number of particles with different sizes filled in PTPD1 and PTPD2 is summarized in Table 2. The total mass of the particles was 5.3 t and 6.3 t, respectively. Schematic diagrams of the particle filling configurations are provided in Figs. 5 and 6.

Vibration reduction analysis under condition 1

The original vibration spectrum of the tower without dampers (Fig. 7) indicated that the vibration energy was predominantly concentrated near 0.3 Hz, with a peak acceleration of 0.409 m/s²—indicating typical ultra-low-frequency vibration. Suppressing such vibrations is crucial for reducing fatigue damage and extending service life.

Acceleration spectra after PTPD installation revealed: For both pendulum lengths, PTPDs filled with 200 mm particles achieved optimal vibration reduction (51.2% and 58.1%); Longer pendulum lengths provided superior damping performance at identical particle sizes.

Vibration reduction analysis under condition 2

Under Condition 2 (Fig. 8), the original peak acceleration increased to 0.555 m/s² at 0.3 Hz.

Post-installation spectra showed: Higher peak accelerations due to increased wind loads; Consistent with Condition 1: PTPDs filled with 200 mm particles yielded the highest reduction rates (49.1% and 55.4%), with longer chords performing better.

Vibration reduction analysis under condition 3

Under Condition 3 (Fig. 9), the original peak acceleration rose further to 0.717 m/s².

Results confirmed: PTPDs filled with 200 mm particles remained optimal (47.6% and 55.4% reduction); Longer pendulum lengths maintained performance superiority.

Figure 10 summarizes peak accelerations across all conditions. Key findings: Particle size below 200 mm reduced mass and increased fluidity, raising collision frequency but lowering energy dissipation per impact; Particle size above 200 mm exhibited the opposite trend; The 200 mm particle size balanced collision frequency and dissipation efficiency; Longer chords accommodated more particles, increasing total dissipative mass and enhancing performance. The optimal particle size results from a trade-off between collision frequency and energy dissipation per collision. This conclusion is drawn from macroscopic response observations; the underlying micro-mechanisms—such as particle velocity distribution, number of collisions, and energy dissipation rate—require further in-depth quantitative investigation through subsequent development of specialized particle motion monitoring and statistical analysis procedures.

Experimental analysis of multi-parameter PTPD vibration reduction

Baseline vibration analysis

This study is based on a prototype horizontal-axis offshore wind turbine. To validate the reliability of the FEM-DEM coupled simulations, a 1:65 geometrically scaled model was designed under existing fabrication and testing conditions, with a fixed tower wall thickness of 1 mm. The scaled wind turbine tower model presented in this study was constructed from stainless steel with a four-segment configuration. The length, top diameter, and bottom diameter of each segment are summarized in Table 3.

Accelerometer placement is shown in Fig. 11. Triaxial accelerometers were magnetically fixed above the top flange (Point 1) and third-highest flange (Point 2) to measure horizontal vibrations at both heights. Simulated wind loads were applied, and vibration signals from Points 1 and 2 were recorded to analyze acceleration responses along the x- and y-axes.

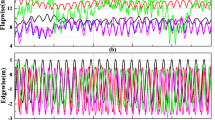

Constrained by laboratory equipment and spatial resources, simulated wind loads were produced using an airflow generator positioned upstream of the scaled wind turbine model to induce blade rotation. Vibration data from sensors at locations P1–P5 were recorded under these simulated wind conditions once steady operational status was attained across various rotational speeds. At a blade rotational speed of 50 r/min, the blade-passing frequency coincided with the tower’s fundamental frequency, resulting in peak acceleration responses observed at the first-order natural frequency of 0.85 Hz. Figure 12 shows a prominent response peak at 0.85 Hz, with amplitude decreasing at lower measurement heights. Vibrations at the upper tower (Point 1) primarily originate from blade-passing frequency and wind loads, indicating pulsating wind and blade motion as the dominant energy sources. Additionally, x-axis vibrations exceeded y-axis responses at the same height. Thus, x-axis vibrations at Point 1 were most significant, demonstrating the highest sensitivity to PTPD performance and the most urgent need for suppression.

Vibration suppression experimental analysis

Based on Eqs. (15)–(16) and scaled dimensions, two PTPD configurations were selected: Pendulum length 500 mm, total mass 10 kg, auxiliary stiffness 76 N/m, particle mass 8 kg; Pendulum length 625 mm, total mass 12 kg, auxiliary stiffness 146 N/m, particle mass 10 kg. PTPDs filled with 8 mm, 10 mm, or 12 mm iron-based particles were installed at Point 1. Acceleration responses were analyzed post-installation, with vibration reduction performance and frequency-domain curves shown in Fig. 13.

Table 4 and experimental spectra (Fig. 14) indicate that the PTPD with a particle size of 10 mm and a chord length of 625 mm achieves the optimal vibration reduction effect of 58.0%. Any deviation from this particle size—either larger or smaller—reduces the damping performance, which aligns with the simulation results showing that an optimal particle size exists for maximizing vibration suppression under various conditions. Similarly, a shorter chord length (500 mm) with the same particle type resulted in decreased performance due to a reduced number of particles, consistent with the simulation conclusion that PTPD1 exhibits slightly lower damping efficiency than PTPD2 owing to its lower total particle count. These consistent trends validate the effectiveness of the coupled FEM-DEM simulation method.

Conclusion

By establishing a 4-DOF tower-PTPD dynamic model and combining FEM-DEM simulations with scaled experiments, this study elucidates PTPD’s multi-parameter vibration suppression mechanism. Key conclusions follow:

-

1)

Particle diameter critically influences energy dissipation efficiency: Particle sizes below 200 mm reduce mass and increase fluidity, raising collision frequency but lowering energy dissipation per impact; Particle sizes above 200 mm exhibit restricted motion due to excessive inertia; The 200 mm particle size optimally balances collision frequency and dissipation, achieving 47.6%–58.1% reduction at 0.3 Hz. Scaled experiments (10 mm equivalent diameter) validated this, reaching 58.0% reduction.

-

2)

Increased pendulum length enhances performance: Longer chords accommodate more particles, strengthening discontinuous medium damping; Simulations showed 3.5 m chords improved reduction rates by 6.9%–7.8% versus 3.0 m chords under identical conditions. Scaled tests (625 mm vs. 500 mm, 10 mm particles) confirmed a 19.9% increase.

-

3)

PTPD maintains stable performance across wind speeds: Simulations demonstrated effective suppression of 0.3 Hz vibrations under mean wind speeds of 12–20 m/s; Peak acceleration reductions consistently exceeded 47.6% at optimal particle sizes, indicating robust adaptability.

However, despite the progress achieved under the current assumptions and conditions, several limitations require further investigation. The study assumed that the pendulum angle of the PTPD is small enough to neglect nonlinear geometric effects, thereby simplifying the model. However, under extreme weather conditions, tower-top displacements and pendulum angles may exceed this assumption, leading to nonlinear effects such as frequency drift. Classical tuning theory treats the PTPD as a rigid mass point, neglecting the time-varying nature of equivalent mass and stiffness resulting from internal particle motion. This time-varying behavior is inherently a nonlinear feature of the PTPD. Further investigation into the time-dependent influence of particle motion on the equivalent dynamic parameters of the PTPD will be a key focus of future theoretical work. Simplifying the complex offshore wind turbine system—including the tower, foundation, and nacelle—into a two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) model may not capture higher-order modes that could be excited in realistic flexible towers with dense modal characteristics, potentially affecting the control performance of the PTPD. Furthermore, the numerical simulations did not consider coupled wind-wave-current interactions, and could not replicate actual load amplitude distributions, phase relationships, or their complex effects on particle motion. Although experiments were conducted using a 1:65 scaled model, particle collision and friction forces are not perfectly scalable. Full-scale or large-scale model tests under real or simulated marine environmental loads are necessary to validate PTPD performance. Additionally, the experimental conditions were relatively idealized, and the excitation methods differed significantly from the broadband, multi-directional excitation typical of real offshore wind and waves, limiting the reproduction of true dynamic responses.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

References

Yan, X. R. et al. Overview of current situation and trend of offshore wind power development in China. J. Power Generation Technol. 45 (1), 1–12 (2024).

Wang, L. Z., Wang, L. L., Hong, Y. & Li, S. Offshore wind power technology development trends. J. Energy Eng. 44 (6), 3–12 (2024).

GWEC. Global offshore wind report 2024.R. Belgium:GWEC. (2024).

Fan, A., Li, L. P., Liu, R., Oyang, M. N. & Chen, S. N. Research on dynamic characteristics of monopile offshore wind turbine tower under different wind speed conditions. J. Power Generation Technol. 45 (2), 312–322 (2024).

Jiang, Y. P. Research on a Fundamental Frequency Analytical Solution and the Dynamic Response of Monopile Structures of Offshore Wind Turbines. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Science and Technology Beijing (2024).

Wang, Z. S., Xu, M. Q. & Peng, Q. Analyzing the dynamic response of an offshore wind turbine with field test data. J. Ocean. Eng. 41 (3), 48–55 (2023).

Son, Z. Q. Research on Characteristic Analysis and Optimized Control of Offshore Wind Turbine in Complex Environment. Ph.D. Dissertation, North China Electric Power University (2023).

He, Q. D., Liu, Q. & Jin, B. Study on vibration energy distribution characteristics of single-pile offshore wind power tower structure. J. Manuf. Autom. 44 (7), 169–173 (2022).

Negro, V., Gutiérrez, L., Santos, J. & Esteban, M. D. Monopiles in offshore wind: preliminary estimate of main dimensions. J. Ocean. Eng. 133 (15), 253–261 (2017).

Karimmirad, M. Offshore energy structures: for wind power, wave energy and hybrid marine platforms. M. Springer. (2014).

Ma, C., Ban, J. & Zi, G. Comparative study on the dynamic responses of monopile and jacket-supported offshore wind turbines considering the pile soil interaction in transitional waters. J. Ocean. Eng. 116564, 292 (2024).

Wang, Z. H. & Chen, Z. Q. Development and performance tests of an eddy-current tuned mass damper with permanent magnets. J. J. Vib. Eng. 26 (3), 374–379 (2013).

Hemmati, A., Oterkus, E. & Khorasanchi, M. Vibration suppression of offshore wind turbine foundations using tuned liquid column dampers and tuned mass dampers. J Ocean Engineering. 172, 286–295 (2019).

Carswell, W., Johansson, J. & Lovholt, F. Foundation damping and the dynamics of offshore wind turbine monopiles. J Renewable Energy. 80, 724–736 (2015).

Sun, C. & Jahangiri, V. Bi-directional vibration control of offshore wind turbines using a 3D pendulum tuned mass damper. J Mechanical Syst. Signal. Processing. 105, 338–360 (2018).

Liu, X., Shi, W. X. S. & Chen, X. Introduction and analysis of the pendulum-type tuned mass damper. J Structural Engineers. 28 (06), 66–71 (2012).

Le, Z. J. et al. Dynamic response of offshore wind towers under wind-wave combined effect and MTMD vibration control. J Noise Vib. Control. 44 (06), 65–72 (2024).

Dong, X. F., Ren, S. W., Yuan, J. & Yu, T. S. Parameter optimization and vibration reduction effect of one C-shaped particle damping-tuned mass damper for offshore wind turbine. J Ocean Engineering. 117856, 305 (2024).

Lu, Z., Zhang, B. C. & Lu, X. L. Shaking table test of steel frame structure with particle tuned mass damper. J Journal Building Structures. 38 (04), 10–17 (2017).

Lu, Z., Rong, K. J. & Ma, Z. C. Experimental study on vibration reduction control of particle tuned mass damper coupled with wind turbine structure. J Journal Building Structures. 44 (04), 267–275 (2023).

Chen, J. L. & Yang, R. C. Vibration control of tuned roling-ball Damperin wind turbines. J J. Tongji university(natural science). 41 (08), 1145–1150 (2013).

Xie, S. Y., He, J., Zhang, C. L. & Jin, X. Vibration control of offshore wind turbines under wind and wave excitations. J Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica. 43 (07), 270–275 (2022).

You, T. & Dissertation Research on performance optimization and vibration control of pendulum tuned mass damper. Ph.D. Shanghai University. (2020).

Wang, W. X. et al. Control performance of pendulum pounding double tuned mass damper under various excitations. J China J. Highw Transp. 35 (7), 154–163 (2022).

Wang, L. K., Shi, W. X., Lu, Z. & Wang, H. T. Research on vibration reduction effect of semi-active pendulum tuned mass damper. J Building Structure. 50 (21), 97–101 (2020).

Xiao, W. Q., Huang, Y. X., Li, W., Lin, H. & Chen, Z. W. Influence of particle damper configurations on the dynamic characteristic for gear transmission system J. J. Mech. Eng. 53 (7), 1–12 (2017).

Xiao, W. Q., Zeng, Y. M., Zhang, X. Y., Pan, H. W. & Ren, X. Y. Research on vibration reduction of particle damping based on finite element-discrete element coupling. J Astronautical Syst. Eng. Technology. 6 (6), 1–8 (2022).

Tian, J. B., Huang, Z. J., Wang, J. & Xiao, W. Q. A study on vibration reduction of ship propulsion shafting based on a particle damper. J Journal Vib. Shock. 41 (24), 97–103 (2022).

Xiao, W. Q. et al. Study on the vibration reduction of internal combustion EMU power pack frame under multiple loading conditions based on particle damping. J Journal Mech. Engineering. 58 (4), 250–257 (2022).

Wang, L. W., Huang, L. L. & Zhang, Z. W. Analysis on power characteristics of offshore wind farm based on measured operational data. J Modern Electr. Power. 37 (05), 532–538 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: This work was supported by the Guangdong basic and applied basic research foundation (2022A1515240049).

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: This work was supported by the Guangdong basic and applied basic research foundation (2022A1515240049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiao, W. Q.; data curation, Xie, Z. P. and Mo, F.; experiment, Xie, Z. P.; writing-original draft, Xie, Z. P.; Writing-review & editing, Yao, W. P. and Cai, Z. Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, W., Xie, Z., Yao, W. et al. Multi-parameter pendulum tuned particle damper for vibration suppression in offshore wind turbine towers. Sci Rep 15, 41966 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25933-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25933-1