Abstract

Keeping the sustainability concept in view, the present study aimed to valorize diatomite for adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) ions from waters and wastewaters. A modified diatomite nanocomposite was prepared via its impregnation with silver nanoparticles, using a one-pot technique, and the silver nanoparticles-diatomite nanocomposite potency was comprehensively investigated for Cr(VI) adsorption. The raw diatomite and silver nanoparticles-diatomite nanocomposite were characterized via XRD, SEM, and BET techniques. A statistical technique, based on response surface method, was exploited for finding the optimized conditions for adsorption. Accordingly, a maximal chromium sorption of 94.0% was observed at pH 4.61, sorption duration 60.37 min, and adsorbent dosage 2 g, for an initial level of 45 mg/L for the composite adsorbent. The equilibrium scrutinization shows that Langmuir isotherm model has a better fitness with the adsorption data. In addition, the adsorption kinetic analyses demonstrated the best fit to the pseudo-second order equation and multiple distinct phases of intraparticle diffusion for both adsorbents. Overall, silver nanoparticles-diatomite nanocomposite showed excellent properties for adsorption of Cr(VI) ions and could be exploited as an adsorbent in full-scale treatment plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is one of the most vital resources for sustaining human life and maintaining ecological balance1. Despite its abundance, challenges such as contaminations threaten access to safe and clean water globally2,3. A significant concern is water pollution by heavy metals, including lead, cadmium, arsenic, chromium, etc. Heavy metals are persist in the environment, are toxic, and tend to bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, posing serious health risks4. For example, chromium contamination levels in some industrial-impacted water bodies have been reported to be between 0.50 and 1.14 ppm5,6, which exceed safe limits established by health authorities. The World Health Organization recommended a maximum allowable concentration of 50 µg/L for chromium in drinking water to prevent adverse health effects7. Chromium is extensively used across various industries, including electroplating, ferrochrome production, pigment manufacturing, and leather tanning. Effluents from these industries often release chromium compounds into the environment, causing significant pollution issues. Of particular concern is hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)), classified as a Group A carcinogen, which is highly toxic and poses carcinogenic risks to humans upon exposure7. These factors reveal the critical need for effective treatment technologies to remove chromium from water sources to safeguard human health and the environment.

Several technologies have been developed for chromium removal from water, each with distinct advantages and drawbacks. Chemical reduction/precipitation is a traditional, cost-effective method with high removal efficiency, even up to 99.6%8. However, it generates sludge which needs careful disposal, posing environmental challenges9. Adsorption methods offer versatile and cost-effective treatment with efficiencies which are sometimes nearly complete removal depending on the adsorbent, such as activated carbon, natural minerals, or nanomaterial-enhanced sorbents, and are favored for ease of operation, regenerability, and sustainability10. Ion exchange can offer selective and efficient removal (e.g. more than 95%), particularly valuable for producing high-purity water, yet initial resin costs and fouling issues limit its use11,12. Membrane filtration achieves very high removal (up to even more than 99%) and compact systems suitable for advanced treatment, but suffers from high energy demands, fouling, and capital costs13. Photocatalytic reduction provides an eco-friendly alternative, enabling simultaneous reduction and removal of Cr(VI)14, though it requires controlled UV light and complex operation. Electrochemical treatment is effective and minimizes waste but is constrained by energy consumption and electrode maintenance14. Overall, adsorption process is proven to have comparatively lower operating costs, easy operation, and less secondary disposal products as waste15. In this context, adsorption-based methods have gained increasing attention due to their simplicity and effectiveness in the rapid treatment of wastewater containing high levels of toxic pollutants16, such as chromium17. However, adsorption performance depends on the nature of the adsorbents15,16. The research community has been looking for the development of highly efficient sorbents with an affordable cost18. So far, different natural absorbents, such as zeolite, clays, biopolymers, and diatomite, have been studied for their merits in adsorption processes towards the removal of different heavy metal contaminants and other pollutants19,20,21,22,23.

Natural adsorbents have emerged as versatile and sustainable materials widely applied in various systems for the removal of pollutants from water, wastewater, and environmental matrices1,24. Due to their abundant availability, eco-friendliness, and cost-effectiveness, natural adsorbents such as diatomite, clays, zeolites, chitosan, and agricultural residues have gained significant attention in water treatment24,25. Such materials demonstrate noteworthy adsorption capacities attributable to their high surface area, porous structures, and functional groups, which facilitate strong interactions with diverse contaminants, including heavy metals, dyes, pharmaceuticals, and organic pollutants26,27. The inherent biodegradability and/or potential for chemical or physical modification enhance their performance and reusability, positioning natural adsorbents as promising candidates in the advancement of green and cost-efficient environmental technologies.

Diatomite (DE) is a highly porous, lightweight, silicon-containing soft rock that is formed by the accumulation of fossilised diatom residues. Diatomite contains mostly SiO2 (50–90%) and lesser amounts of Al2O3, CaO, and Fe2O3, in addition to minor components, such as Na2O, SO3, V2O5, TiO2, and MnO228. DE has been previously investigated for the adsorption of chromium from water28,29,30. Because of its high adsorption effectiveness, which is possibly ingrained in excess oxygen bridges, coordination defects, and a large number of surface silicon hydroxyl groups that have significant affinities for different contaminants, it has shown great promise as an adsorbent for a variety of pollutants28.. Recent studies indicate that nanomaterial-modified diatomite is receiving increased attention due to its key properties, including a large specific surface area, high adsorption capacity, and excellent stability21. When adding nanoparticles to the structure of most adsorbents, agglomeration frequently occurs, reducing the surface area and, as a result, the adsorption capacity31.. However, in the case of diatomite, its abundant surface silicon hydroxyl bridges may interact with metals or metal oxides, potentially preventing agglomeration and may result in substantial adsorptive performance improvement. Previously, nickel/nickel oxide32, niobium(v) oxide31, iron oxide33, and manganese oxide34 modified diatomite adsorbents were studied for the adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) from water.

This study explores the innovative use of silver nanoparticle-modified diatomite as an effective adsorbent for the removal of hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI)) from aqueous solutions. Previous research has demonstrated the enhanced Cr(VI) adsorption capabilities of activated carbon coated with silver nanoparticles35. Therefore, the current work designed to take the advantages of the dual functionality of silver nanoparticles, since not only do they significantly improve adsorption efficiency, but they also facilitate the reduction of toxic and highly mobile Cr(VI) to the less toxic and more stable trivalent chromium (Cr(III))7,36. Such reduction represents a cost-effective and environmentally favorable strategy for chromium remediation36. Addressing a critical gap in current adsorbent development, the present work innovatively integrates silver nanoparticles within a purified and thermally treated diatomite matrix through impregnation. The sequential purification of raw diatomite via nitric acid treatment and thermal calcination ensures an optimized substrate, which upon modification with silver nanoparticles, exhibits superior performance in Cr(VI) removal. This novel composite combines the inherent adsorption properties of diatomite with the catalytic and reductive advantages of silver nanoparticles, presenting a compelling advancement in sustainable wastewater treatment technologies.

Experimental

Materials

Raw diatomite was obtained from Adami-Tulu, Oromia region, Ethiopia. HNO3 (65%), silver nitrate (99%), HCl (37%), diphenyl carbazide, LiBO2, HF, KBr, and potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) obtained from Merck were used as received. All the chemicals used in the study are of reagent grade and were exploited without any further purifications.

Diatomite adsorbent Preparation

The raw diatomite (RDE) was pre-treated by chemical treatment with nitric acid, followed by thermal calcination, adopting a previously reported procedure with some modifications37. The RDE sample was crushed and washed with pure distilled water by mixing at 500 rpm for 30 min. Then, it was leached using 2 M HNO3 with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (g/mL) at 120 °C with continuous mixing at 500 rpm for 8 h. The acid-treated diatomite was filtered and washed several times with deionized water till the pH of the washing water reached 7.0. Further, it was dried in an oven at 100 °C for 24 h. The dried sample was then ground and sieved with a 45 μm sieve. The acid-treated diatomite was finally calcinated in a muffle furnace at different temperatures (500, 600, and 700 °C) for 4 h. The thermally processed diatomite (PDE) was kept in a sealed container until further use.

Composite adsorbent Preparation

The nanocomposite adsorbent was synthesized using the in-situ reduction method, using previously reported conditions, with some modifications38. For this purpose, 500 mL of a 35 mM AgNO3 solution was prepared using deionized water. PDE (60 g) was mixed with the AgNO3 solution and subjected to heat at 60 °C for 5 h to attach silver ions to the surface of diatomite structures. Then, the silver nanoparticles (AgNpS) modified diatomite was dispersed in 1.0 L of deionized water for 10 min, and filtered to remove the non-attached silver ions. Afterwards, 50 mL of 35% tri-sodium citrate was added drop by drop to the resulting solution and was kept for 1 h at 25 °C to form the silver nanoparticles-diatomite (AgNps-DE) nanocomposite. Finally, the nanocomposite was recovered through filtration and dried in an oven at 100 °C for 3 h.

Characterizations

Compositions of raw diatomite (RDE) and modified diatomite (PDE) were carried out using atomic absorption spectroscopy (Analyst 700 Perkin-Elmer AAS). The samples were fused in LiBO2 and dissolved in HF, and then characterized by atomic absorption spectroscopy. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis for diatomite was taken using x-ray diffractometer (D8 VENTURE, Bruker Systems, Japan). The XRD pattern was set to obtain a 2θ range of 5.0–80.0. The specific surface area of the prepared samples has been determined using a Brunauer-Emmett-Teller instrument (SA-9600 series, HORIBA, USA). The morphological characteristics of the diatomite were studied using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Inspect Instruments, F50 SEM, Japan). By digesting the sample with HNO3, the amount of AgNps immobilized on the PDE was measured and calculated using the previously described methodology38,39.

Adsorption study

The adsorption performances of the PDE and AgNps-DE were studied at Cr(VI) initial concentrations (10–30 mg/L), adsorbent concentration (5–30 g/L), temperature (25–55 °C), adsorption times (30–120 min), and solution pH (4.0–8.0) using batch adsorption process. In all the batch experiments, 100 mL of Cr(VI) aqueous solution was transferred to 250 mL glass flasks, and predetermined nanocomposite samples (0.5, 1, 2, and 3 g) were added to Cr(VI) solution. Then, the solutions were stirred using a magnetic stirrer. Finally, the Cr(VI) concentration in water was determined by exploiting a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (JASCO V770, Oxford Instruments, UK) at 540 nm using the colorimetric method with the 1,5-diphenylcarbazide complex at a pH of 1.0 using the method previously reported4,30 The Cr(VI) removal efficiency were calculated using from the correlation given in Eq. (1).

In this equation, C0 and Ct are the initial Cr(VI) and final Cr(VI) concentration, respectively, in mg/L.

Response surface methodology

In recent times, a software-developed numerical model that generates the relationship among the selected key factors and the response through response surface methodology (RSM) has gained more interest for process model development and optimization of the process4,40. In this study, RSM-based Box-Behnken design (BBD) was used to develop the model and generate response surfaces to evaluate the effect of selected process variables (pH, agitation duration, and dosage of adsorbent) on the Cr(VI) removal. The selected key factors and their corresponding ranges were determined from the preliminary screening experiments, which are depicted in Table 1. In this study, as per BBD, a total of 17 experimental runs were performed, and among them, there were 5 centre points. The different combinations of parameters were used to conduct the adsorption experiments, and the response surface model and model analysis were performed using Design Expert (Version 13.0, Stat-Ease Inc., USA). A second-order polynomial equation was fitted to establish the relationship between the factors and response as shown in Eq. (2).

where, Y denotes the response, that is, Cr(VI) removal (%), xi denotes the selected variable (pH, contact time, and adsorbent dose), and βi refers to the corresponding coefficient. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to analyze the suitability of the model. The 3-D response surface curves were generated to visualize the interaction effects of the selected factors on the Cr(VI) removal. Further, a second-order model correlating the factors and responses was developed, and then it was statistically verified.

Adsorption isotherm

Adsorption isotherm analysis provides a good understanding of what may be happening while carrying out the processing of adsorption. In this work, adsorption isotherm data were acquired for both PDE and AgNps-DE. The adsorption experiments were conducted using various quantities of adsorbent (0.5, 1, 2, and 3 g). The experiments optimum conditions obtained from the Response Surface Methodology. At equilibrium, the amount of Cr(VI) that was adsorbed into the prepared adsorbent (mg/g), denoted as qe, was estimated using Eq. (3).

where, C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentration of Cr(VI) (mg/L), respectively. m is the mass of the sorbent (g), and V is the volume of Cr(VI) solution (L). From the adsorption results, the data were fitted to various isotherm models.

Adsorption kinetics

To appraise sorption data towards kinetic analysis, 100 mL aqueous solution having 20 mg/L Cr(VI) was taken into 250 mL flasks. In each flask, 1.0 g of adsorbent was added. The solutions were continuously mixed with a magnetic stirrer, keeping the pH value at 4.0 and the temperature at 35 °C. The concentrations of Cr(VI) in the aqueous solution were measured at different times and fitted to various kinetic models.

Results and discussion

Characterizations

Diatomite compositions

The compositions of RDE and PDE are reported in Table 2. In general, the chemical composition of diatomites can be classified into three categories: main, secondary, and minor28. Silica is a major diatomite component, followed by secondary components, such as aluminum oxide, iron oxide, and calcium oxide. The minor components are represented by other metal oxides, such as MgO, Na2O, K2O, SO3, V2O5, TiO2, MnO2, and some organic and inorganic compounds. For the current raw diatomite (RDE), silica content was found to be 75.8%, while the contents of Al2O3 and Fe2O3 were 7.3% and 3.6%, respectively. The silica content of the current diatomite is slightly lower than the value previously reported by Weldemariam et al.41 for a diatomite sample taken from the same area, that is, the Adami Tulu area of Ethiopia. In general, the silica content of this deposit is in the range reported for most deposits from different countries (Table 2). It also has a lesser loss of ignition, that is, lower in organic content and carbonates. The secondary components (Al2O3 and Fe2O3) and minor components are also in the range reported for raw diatomite from different countries. Table 3 shows the comparison of composition for raw diatomite (RDE) and diatomite thermally treated at 600 °C. The composition of silica was found to rise under chemical and thermal treatments, whilst the composition of the majority of secondary and minor elements tended to decrease. While the calcination procedure removes moisture and organic contaminants, the acid treatment may result in the reduction of metal oxides42.

The amount of silver nanoparticles loaded on the treated diatomite was determined by acid digestion using AAS. It was found that the amount of silver loaded on diatomite was 28 mg/g. The value is in the range (24 to 46.6 mg/g) of AgNps loading on diatomite previously reported by Panáček et al39.. The amount of AgNps attached to the diatomite in the current work was observed to be higher than the value reported (0.537 wt%) by Xia et al38.. This variation could be due to the differences in the AgNps-DE pre-processing techniques and other parameters, such as initial AgNps concentration and mixing conditions.

SEM and XRD analyses

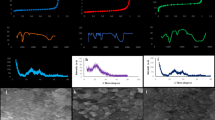

The SEM images of the RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE composite are displayed in Fig. 1. The SEM image of the RDE had a more compacted structure with some areas of uniform porous spots (Fig. 1 (a1 − 2). A complicated porous structure made up of fragmented, overlapping frustules is shown in the micrograph. As is typical of diatomite, these frustules have a large surface area, uneven forms, and porous channels. The SEM images of the PDE became more churned due to removing impurities from the diatomite structure, as shown in Fig. 1 (a1 − 2). In addition, the surface of PDE seemed to be smooth due to the removal of the impurities by chemical and thermal treatments. Sharper edges and clearer pore outlines are visible at closer range, indicating that both organic and inorganic contaminants have been eliminated. Moreover, certain morphological alterations or partial deterioration of the frustule edges can be observed for the treated diatomite, which could be due to thermal treatment at high temperatures. Although some of the frustules seem slightly crumpled or fragmented, the porous architecture is still visible. The SEM image of AgNps-DE composite in Fig. 1 (c1 − 2). Diatom frustules appear structurally intact and well-preserved upon impregnation with silver nanoparticles, displaying distinctive porous walls and ornamentation. Effective acid leaching and thermal treatment are indicated by the surface’s cleanliness and sharpness. Small bright spots or clusters could represent AgNPs distributed on or within the pores of the frustules.

The XRD spectrum of RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE is shown in Fig. 2. The XRD spectra of the RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE had broad peaks ranging between 12 and 33° with a diffused peak, indicating that RDE, PDE and AgNps-DE were less ordered and less crystalline. The minor crystalline phases that are indicated at 2θ of 26° and 27° may correspond to kaolinite and quartz. The XRD results of the current diatomite are consistent with the results reported for samples collected from different locations44,45,46. Acid and thermal treatment slightly reduced the kaolinite and quartz as the corresponding peaks diminished. It can also be observed that the chemical and thermal treatment, as well as the impregnation of silver nanoparticles on its structure, did not change the amorphous nature of the diatomite.

BET surface areas

The BET surface areas of the RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE were determined using the BET surface analyzer and are depicted in Table 4. The current BET value (17.4) for the RDE was found to be in good agreement with the value (20 m2/g) reported by Weldemariam et al41. for the sample collected the sample from the same area. However, the BET area of the treated diatomite in this work was much higher than the value (maximum value of 29.0 m2/g) reported by Weldemariam et al41.. In this work, the sample calcinated at 600 °C showed a maximum surface area (56.0 m2/g). This may be due to the application of a combination of both HNO3 and thermal treatment. The BET surface area of treated DE was also comparable with the values reported for treated DE from some regions, such as Iran (57 m2/g)42. However, it is lower than the value reported for other regions, such as Egypt (195 m2/g)37. Further, the incorporation of AgNps in the diatomite structure slightly reduced in BET surface area to 39 m2/g, as shown in Table 4. This could be related to the reduction of pore sizes in the diatomite structure due to the impregnation of AgNps. The BET result is in good agreement with the SEM images.

Adsorption studies

Before examining how adsorption parameters affect the efficiency of Cr(VI) removal, the performance of Cr(VI) removal was compared for RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE composite under fixed conditions. To do this, 1.0 g of each adsorbent (RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE) was added to 100 mL of 10 mg/L Cr(VI) aqueous solution at pH 4.0 and 25 °C and continuously mixed for 1.0 h. According to the results, the removal efficiencies of Cr(VI) for RDE, PDE, and AgNps-DE were 43, 50, and 85%, respectively. As expected, the higher adsorption by the AgNps-DE might be due to the active functional groups related to silver nanoparticles, which could enhance the interaction of the composite with the dissolved Cr(VI) ions47,48. Therefore, for further adsorption studies, PDE and AgNps-DE were used and compared.

Effect of pH

The influence of pH on the adsorptive removal of chromium (Cr (VI)) is depicted in Fig. 3(a). In this experiment, 1.0 g of each adsorbent (PDE and AgNps-DE) was added to 100 mL of Cr(VI) aqueous solution of 10 mg/L Cr(VI) and mixed for 100 min at 25 °C. The solution pH was varied from 2 to 8 by adjusting with NaOH and HCl. The results show that maximum removal percentages of 66.3% and 95.8% for PDE and AgNps-DE, respectively, at a solution pH of 4.0. Hence, in comparison to PDE, the AgNps-DE composite shows better Cr(VI) removal efficiency. It is apparent that the pH of the media affects the adsorbent’s surface charge, ionization degree, and speciation of the chromium ions49. As is well known, depending on the pH of the solution, chromium can exist in a variety of anion forms, including HCrO4−, Cr2O72−, and CrO450. Hence, at pH 1.0 to 4.0, HCrO4− can be the dominant form of hexavalent chromium in solution50.

As media pH increases from 2.0 to 4.0, the removal percentage of both PDE and AgNps-DE increases and reaches 66.3% and 95.8% for PDE and AgNps-DE, respectively. At lower pH values, the surface of diatomite might be positively charged since silanol (Si-O) and Si-O-Al groups on the diatomite surfaces are protonated due to the existence of excess H+ in the medium, blocking the chromate ions from adsorption on the surface49,51. Increasing the solution pH may result in deprotonation of the active adsorbent site, which may increase the chromium metal adsorption on the sites49,52. In the case of the lower concentration range, the ratio of the initial number of adsorbate to the available sorption sites is low, and the sorption becomes independent of initial concentration, which enables the complete ions19. That is, the competition between excess hydrogen ions and Cr(VI) species to attach contact with the active sites of adsorbents reduces the absorption of Cr(VI)53. On the other hand, the formation of dihydrogen chromate could also exist from Cr(VI) species at lower pH54. Further increase in the pH gave rise to the decline in Cr(VI) removal. This could be attributed to the loss of active sites of the adsorbent and changes in Cr(VI) species49.

Effect of temperature

To examine the effect of temperature on adsorption, the experiment was carried out using 100 mL aqueous solutions containing 50 mg/L of Cr(VI) at a pH of 4.0, employing 1.0 g of adsorbents in each test. The solutions were mixed continuously for 100 min, and the temperature was varied from 15 to 55 °C. The effect of temperature on Cr(VI) removal is illustrated in Fig. 3(b). From the results, the adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) increased with temperature from 15 to 45 °C for both adsorbents, reaching 67.1 and 95.2% for RDE and AgNps-DE, respectively. The increase in temperature enhances the kinetic energy of the particles, which brings about the migration of ions from the bulk fluid into the surface of the adsorbent, and then into the pores of the adsorbent to interact with the active sites55. This was in agreement with previously reported works on the effect of temperature on the adsorption of Cr(VI) with various adsorbents20. Nevertheless, further increments in temperature resulted in a decline removal of Cr(VI) which led to the support of desorption of Cr(VI) which reduced the net absorption of the Cr ions53.

Effect of adsorbent dosage

To examine the impact of adsorbent dosage on Cr(VI) removal, 100 mL of Cr(VI) aqueous solution containing 50 mg/L of Cr(VI) was tested at a pH of 4.0, 25 °C for 100 min. To check the impact of adsorbent dosage on adsorptive removal of Cr(VI), different dosages (0.2 g to 2 g) of PDE and AgNps-DE were added in each flask. The results are depicted in Fig. 3(c). As can be seen from Fig. 3(c), while the adsorbent dosage increased from 0.2 to 3 g, the removal efficiency of Cr(VI) was also found to be increased for both adsorbents. The maximal adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) was 72.1% and 93.9% for PDE and AgNps-DE, respectively. The Cr(VI) removal can be increased with adsorbent dosage, which is directly related to the availability of adsorption sites56. Hence, the rate of removal of Cr(VI) gradually declined with the adsorbent dosage, that is, the lower removal efficiency obtained at lower adsorbent dosage, while an increment in Cr(VI) removal was found at higher adsorbent dosage.

Effect of initial Cr(VI) concentration

To study the effect of initial Cr(VI) concentrations, 100 mL of aqueous solution with various levels of Cr(VI) (5 to 100 mg/L) was tested by adding 1.0 g of adsorbent. The pH was adjusted to 4.0, and adsorption studies were conducted at 25 °C for 100 min. The result is shown in Fig. 3(d). As the initial level (Cr(VI) concentration increased from 5 to 100 mg/L, the Cr(VI) removal increased to 40.3 and 78.1% for PDE and AgNps-DE, respectively. A further increase in Cr concentration was found to result in a decline in the removal efficiency. An increase in the initial Cr(VI) concentration can strengthen the driving force needed to overcome mass transfer resistance, thereby facilitating the adsorption from the aqueous solution onto solid supports55. However, when the concentration exceeds a certain value, the adsorption capacity of Cr(VI) declines because of the limited availability of the active sites. In such a way, the adsorption status was decided by considering the amount of available active sites till they were saturated56.

Effect on adsorption time

The effect of contact time on the adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) was studied using 100 mL aqueous chromium solution with 50 mg/L Cr(VI) by adding 1.0 g of adsorbents (Fig. 3(e). It was demonstrated that the removal of Cr(VI) increased with contact time. In case of AgNps-DE, the removal of Cr(VI) dramatically increased from 0 to 75% as the contact time increased from 0 to 20 min; however, for PDE, it increased from 0 to 40% in 50 min. In the first 20 min, the adsorption was rapid due to free sites on the adsorbent surface for Cr(VI) binding57. A rapid increase in Cr(VI) removal was observed during the initial stage; however, the rate of removal gradually declined after 50 min for AgNPs-DE and 70 min for PDE, likely due to the saturation of available surface sites.

Experimental design and statistical analyses

The effect of three selected factors, that are, adsorption time, dosage of adsorbent, and solution pH, on the adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) by AgNPs-DE was investigated by applying the Response Surface Method based on BBD. AgNPs-DE was selected for optimization of the adsorption parameter because it showed better adsorption efficiency. A total of 17 experimental runs were conducted to develop the response surface model. Accordingly, 2nd order polynomial equation was established that provides a relationship between the three selected independent factors and the Cr(VI) removal as a response. The statistical fitness of the response surface quadratic model was analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), the same is depicted in Table 5. In this regard, the terms are represented as quite significant while the p-value is found to be less than 0.05. As per ANOVA, the calculated p-value for the main and interaction parameters was observed to be low enough, with the R2 value, 0.977. It shows that the generated model was very good at representing the relation between the adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) and the selected factors affecting the adsorption performance. In addition, for the significance of the overall model, the F-value of 75.75 and p-value less than 0.05 showed it is significant. The quadratic equation representing the relationship between the selected independent variable and the response is given in Eq. (14).

where, Y is the Cr(VI) removal percentage, A is the solution pH, B is the contact time (min), and C is the adsorbent dosage (g/100 mL).

Figure 4 shows the developed response surface plots that represent the relationship of Cr(VI) removal with selected parameters. Figure 4(a) shows that the percentage of Cr(VI) removed rises as the adsorbent dosage increases from 0.5 to 2 g. At the same time, it was found that the Cr removal increased with contact duration as it increased from 30 to 60 min. However, when we increased the adsorption time further, the capacity to remove Cr(VI) was nearly constant. As pH rises from 2.0 to 5.0 and the adsorption period increases from 30 to 60 min, the percentage of Cr(VI) elimination increases (Fig. 4 (a)). However, a further increase in pH and adsorption time reduces the adsorption of Cr(VI). Cr(VI) adsorption increases with rising adsorbent dosages at a lower pH value, and a further increase in pH was found to reduce adsorption. From the statistical analysis, the maximum Cr(VI) removal of 92% was predicted at adsorption time, 60 min; pH value, 5.0; adsorbent dosage, 2 g; and initial level of Cr(VI), 45 mg/L.

Kinetics study

To investigate the kinetic aspects and interactions between Cr (VI) and adsorbents, adsorption kinetics was adopted to analyze the relationship between Cr (VI) removal and elapsed time. In this context, various kinetic models are utilized, specifically the nonlinear pseudo-first-order (NPFO), nonlinear pseudo-second-order (NPSO), and intra-particle diffusion models, to assess the goodness-of-fit of experimental adsorption data (Fig. 5a). The following indices were used for evaluations:

where, qe,exp and qe,cal are, respectively, the experimental and predicted capacities (mg/g), qe,mean is the average amount of the experimental adsorption capacity (mg/g), p is the number of parameters in models, and n is the number of experimental data. The highest goodness-of-fit is of the model with highest value of R2adj and R2, and lowest amounts for other indices.

The pseudo-second-order kinetic model proved to be more appropriate for describing the sorption process of Cr (VI) for both adsorbents, as Table 6 illustrates. This model indicates that, for both PDE and AgNPs/De, the interaction of Cr(VI) ions with the adsorbents’ sorption sites is the rate-controlling stage in the overall adsorption mechanism58,59. This conclusion was further validated by testing the Ritche kinetic model. The Ritche’s equation can be given as:

where, qt is the sorption capacity (mg/g) at any time (t), and KR is the constant of Ritchie (min− 1). The assessments (see Fig. 5a; Table 6) showed that the Ritche model also affirms that the adsorption process has a second-order nature, again indicating that the interaction of Cr(VI) ions with the adsorbents’ adsorption sites is the rate-controlling step. However, the results in Table 6 show that the value of k2 (the constant of pseudo-second order kinetic model) for AgNPs/DE (4.61 min− 1) was much greater than that of PDE (2.66), which shows the higher rate of adsorption of Cr (VI) for AgNPs-DE, compared to DE.

In addition to the above kinetic models, two other models (Elovich and Avrami models) were also fitted with the data. These models can be given as the following equations, respectively:

In these equations, the initial adsorption rate is represented by α (mg/g.min), while β (g/mg) indicates the degree of surface coverage and the activation energy associated with chemisorption.

Moreover, the Avrami kinetic constant is denoted as kAV (1/min), and nAV refers to a fractional order of adsorption that corresponds to the specific adsorption mechanism. The results (Fig. 5a; Table 6) showed that the finesses of the Elovich and Avrami models are not as good as pseudo-second order (NPSO) and Ritchie models. Nevertheless, inspecting the values of nAV for both AgNPs/DE and DE adsorbents, 0.247 and 0.091, respectively, shows that they lie between 0 and 1, revealing the possibility that the adsorption process is primarily governed by diffusion60. Consequently, the intraparticle diffusion model’s multilinearity was tested. As can be observed, the plots illustrated in Fig. 5b show the presence of multilinearity for the intraparticle diffusion model, indicating the presence of multiple distinct phases in the adsorption processes of Cr (VI) on both AgNPs/DE and DE adsorbents (Table 6). The graph shows that the initial phases, marked by rapid adsorption on the external surface, are completed within the first 6 (for AgNPs/DE) and 10 (for DE) min. This is followed by a controlled intraparticle diffusion phase (step 2), which lasts from 6 to 20 min for AgNPs/DE and from 10 to 30 min for AgNPs/DE). After this period, the equilibrium adsorption phase (stage 3) begins, occurring after 50 min (for AgNPs/DE) and 90 min (for DE). The values of intercepts for the first stage (in both cases) are negative, which underscores the probability of external surface adsorption and film diffusion control in the very initial steps of adsorption of Cr (VI) on both AgNPs/DE and DE adsorbents61.

Kinetic analyses on Cr(VI) adsorption by AgNps-DE and PDE, using various models (a); fitting data with a multi-stage intra-particle diffusion model for both AgNps-DE and PDE (b); the assessment of appropriateness of adsorption isotherm models for experimental data, using different models for both AgNps-DE (c) and PDE (d); and Vant’ Hoff model for both AgNps-DE (e) and PDE (f).

Adsorption isotherm studies

The adsorption equilibrium of Cr(VI) onto both AgNps-DE and PDE was investigated and compared through the application of various two-parameter adsorption isotherm models, viz. the Langmuir, Dubinin-Radushkevich (D.R.), Freundlich, and Temkin isotherms. The Langmuir isotherm is predicated on the assumption of monolayer adsorption occurring at homogeneously distributed adsorption sites that exhibit uniform affinity for the Cr (VI) ions62,63. In contrast, the Freundlich isotherm model claims that adsorption occurs in multilayers on a heterogeneous adsorbent surface, characterized by varying affinities among sorption sites62,64. The Temkin isotherm, on the other hand, assumes a linear decrease in the heat of adsorption with increasing surface coverage, indicating a uniform distribution of binding energies that reflects sorbent-solute interactions65. Figure 5d illustrates the fitting of experimental data to non-linear representations of the Langmuir, D.R., Freundlich, and Temkin adsorption isotherms for Cr (VI) adsorption on both AgNps-DE (Fig. 5c) and PDE (Fig. 5d), and Table 4 reports the obtained parameters and values of statistical indices (Eqs. (14)-(17). In addition, the mentioned figures (Figs. 5c and d) demonstrate the visual fitness of isothermal studies with the following three parameters, which were exploited for a better understanding of the equilibrium aspect of Cr (VI) adsorption on AgNps-DE and PDE.

Redlich-Peterson isotherm:

Khan isotherm:

Toth isotherm:

Sips isotherm:

where qe and qm are the equilibrium and theoretical maximal capacities, respectively, and other parameters have been introduced in the literature elaborately58,66.

Based on the results shown in Table 6, among the two-parameter models, the Langmuir isotherm seems to be able to provide a successful theoretical framework for understanding the adsorption of Cr(VI) onto both adsorbents, establishing a relationship between the amount of Cr(VI) adsorbed (in mg/g) and its equilibrium concentration in solution (in mg/L). This model has been effectively employed to describe adsorption equilibria in various single- and multi-component systems67. For AgNps-DE, the Langmuir constants, qm and KL, were determined to be 10.99 mg/g and 0.11 L/mg, respectively, which are considerably higher than those of PDE (i.e., 5.76 mg/g and 0.04 L/mg). These results demonstrate that both the adsorption capacity and the affinity of AgNps-DE are higher for Cr (VI) adsorption, compared with PDE.

Among the three-isotherm models, the Sips model showed better fitness with the equilibrium results (see Table 6), even in comparison to the Langmuir model. The Sips isotherm model integrates the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherms, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding adsorption behavior for adsorbates. At low concentrations, the Sips model converges to the Freundlich isotherm, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the adsorption sites. Conversely, at elevated concentrations, it approaches the Langmuir isotherm, which characterizes monolayer adsorption capacities60. In the current work, the n values (obtained from Sips model) for both AgNps-DE and PDE are close to unity. Based on such findings reported by Sajjadi et al68. and Pérez-Marín et al69., the isothermal analysis suggests that, along with Sips model, the Langmuir isotherm provides the most accurate representation of this Cr (VI) adsorption process on both AgNps-DE and PDE. These findings indicate that the adsorption of Cr (VI) ions onto both AgNps-DE and PDE conforms to a monolayer adsorption model characterized by homogeneous coverage.

Thermodynamic aspects and adsorption mechanisms

In addition to the above comparisons, thermodynamic parameters aspects governing the adsorption processes of Cr (VI) on two adsorbents were also examined to compare the mechanism of adsorption on pre-treated diatomite (PDE) with that on silver nanoparticles modified diatomite (AgNPs/DE). The Van’t Hoff equation was used to clarify the nature of adsorption and the underlying mechanisms70,71.

By the aid of Van’t Hoff equation (the above relation), one can plot lnKC versus 1/T (Kelvin− 1) and obtain enthalpy change (ΔH°; J/mol) from the slope and entropy change (ΔS°; J/mol.K) from the intercept. In Eq. (18), R is the gas constant, and KC is obtained from the isothermal data at different temperatures and the Sips (or Langmuir) constants, which are the best isotherms for describing the equilibrium adsorption of Cr (VI) on both studied adsorbents. The derivation of the needed dimensionless thermodynamic constant was obtained from the following relation58.

where, KL is the isotherm constant at the studied temperatures (288.15, 298.15, 308.15, and 318.15) and AWCr is the molecular weight of the Cr element. Also, the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), can be obtained from the following relation:

The related plots were shown in Fig. 5e and f, and the thermodynamic results were summarized in Table 7.

The results indicate that the adsorption of Cr (VI) on PDE is primarily a physicochemical process, supported by the enthalpy change value (16.84)58, which suggests that physicochemical interactions, such as ion-exchange, play a significant role in this type of adsorption. The endothermic nature of the process, indicated by a positive ΔH° is aligned with findings from adsorption of Cr(VI) removal by Pinecone biochar72, amino-functionalized palm oil fibres73, etc. In contrast, the adsorption of Cr (VI) on AgNPs/DE is associated with a high positive ΔH° value (41.21), which reveals that chemisorption has a great share in the process, though a part of Cr (VI) may still be adsorbed by the physicochemical mechanisms like ion-exchange. The presence of silver nanoparticles enhances the reduction potential, facilitating electron transfer between Cr (VI) ions and the AgNPs. This interaction results in a stronger binding affinity, as evidenced by a high positive ΔH (and lower ΔS° value), suggesting that chemical adsorption occurs during the adsorption process. The reduction of Cr (VI) to less toxic forms, such as Cr (III), is a critical aspect of this mechanism, highlighting the dual role of AgNPs as both adsorbents and reducing agents74. In addition, the calculated values for ΔG° were negative for both adsorbents, indicating spontaneous adsorption under the studied conditions. However, the magnitude of ΔG° was significantly lower for AgNPs/DE, compared to PDE, reinforcing the fact that chemisorption on AgNPs/DE is more predominant. Such findings not only contribute to our understanding of Cr (VI) removal from waters and wastewaters but also underscore the potential advantages of using nanomaterials for adsorption purposes.

Conclusions

The comprehensive studies in the current work demonstrated the efficiency of silver nanoparticles-modified diatomite (AgNps-DE) for the removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solutions. The effects of selected parameters, such as adsorption time, solution pH, dosage of adsorbent, and initial concentration of Cr(VI) were investigated on the removal of Cr(VI) by both Ag nanoparticle-modified diatomite (AgNps-DE) and pretreated diatomite (PDE) and compared with each other. In all cases, the AgNps-DE performance was superior to PDE. The incorporation of silver nanoparticles significantly enhanced the adsorptive capacity, achieving a maximum removal efficiency of 94% under optimized conditions: a pH of 4.6, an adsorption time of 60.4 min, and an adsorbent dosage of 2 g at an initial Cr(VI) concentration of 45 mg/L. This performance outstripped that of pretreated diatomite (PDE), confirming the superior efficacy of AgNps-DE in Cr(VI) remediation. The adsorption processes were describable by the Langmuir isotherm model, indicating monolayer adsorption on homogeneous surfaces, with AgNps-DE exhibiting higher adsorption capacity (10.99 mg/g) compared to PDE (5.76 mg/g). Kinetic studies revealed that the pseudo-second-order model best described the adsorption kinetics, implying that the rate-limiting step is predominantly related to the interaction between Cr(VI) ions and the active sites on the adsorbents. The presence of multiple distinct phases in the adsorption process was confirmed through intraparticle diffusion analyses, highlighting rapid external surface adsorption followed by controlled intraparticle diffusion phases. Thermodynamic assessments indicated that the adsorption processes were spontaneous and endothermic for both adsorbents, with chemisorption playing a significant role in AgNps-DE due to the reduction of Cr (VI) facilitated by silver nanoparticles. Overall, these findings underscore the potential of AgNps-DE as an efficient and environmentally-friendly sorbent for Cr(VI) removal from contaminated waters and wastewaters, paving the way for future applications in full-scale wastewater treatment plants.

Data availability

The essential data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gharaghani, M. A. et al. An effective magnetic nanobiocomposite: Preparation, characterization and its application for adsorption removal of P-nitroaniline from aquatic environments. Environ. Res. 246, 118128 (2024).

Musie, W. & Gonfa, G. Fresh water resource, scarcity, water salinity challenges and possible remedies: A review. Heliyon 9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18685 (2023).

Pourshaban-Mazandarani, M., Ahmadian, M., Nasiri, A. & Poormohammadi, A. CuCoFe2O4@ AC magnetic nanocomposite as a novel heterogeneous Fenton-like nanocatalyst for Ciprofloxacin degradation from aqueous solutions. Appl. Water Sci. 13, 179 (2023).

Shewatatek, S., Gonfa, G., Hailegiorgis, S. M. & Tessema, B. Response surface optimization of chromium (iv) removal with Teff straw-based activated carbon. Results Chem. 15, 102168 (2025).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Assessment of drinking water quality and identifying pollution sources in a chromite mining region. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 136050 (2024).

Ahmad, T. et al. Chromium accumulation in soil, water and forage samples in automobile emission area. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28, 3517–3522 (2021).

Nemati, S. S., Dehghan, G., Khataee, A., Alidokht, L. & Kudaibergenov, N. Layered double hydroxides as versatile materials for detoxification of hexavalent chromium: Mechanism, kinetics, and environmental factors. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114742 (2024).

Chen, Q., Luo, Z., Hills, C., Xue, G. & Tyrer, M. Precipitation of heavy metals from wastewater using simulated flue gas: sequent additions of fly ash, lime and carbon dioxide. Water Res. 43, 2605–2614 (2009).

Ata, R., Merdan, G. F. & Töre, G. Y. in Removal of Refractory Pollutants from Wastewater Treatment Plants 137–184CRC Press, (2021).

Liu, B. et al. Removal of chromium species by adsorption: fundamental principles, newly developed adsorbents and future perspectives. Molecules 28, 639 (2023).

Bodzek, M. & Konieczny, K. In Innovative Materials and Methods for Water Treatment: Solutions for Arsenic and Chromium Removal Vol. 2 (CRC, 2016).

Itankar, N. & Patil, Y. Assessing physicochemical technologies for removing hexavalent chromium from contaminated waters—An overview and future research directions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 233, 355 (2022).

Peng, H. & Guo, J. Removal of chromium from wastewater by membrane filtration, chemical precipitation, ion exchange, adsorption electrocoagulation, electrochemical reduction, electrodialysis, electrodeionization, photocatalysis and nanotechnology: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 18, 2055–2068 (2020).

Tian, G. et al. Bi-layered cellulose-based aerogel with photothermal and photocatalytic dual functions for integrated solar-driven desalination and cr (VI) reduction. Chemical Eng. J. 519, 165638 (2025).

Zahakifar, F. et al. Intensification of cr (VI) adsorption using activated carbon adsorbent modified with ammonium persulfate. Sci. Rep. 14, 16949 (2024).

Amirmahani, N., Mahdizadeh, H., Seyedi, N., Nasiri, A. & Yazdanpanah, G. Synthesis and performance evaluation of chitosan/zinc oxide nanocomposite as a highly efficient adsorbent in the removal of reactive red 198 from water. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 70, 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/jccs.202200514 (2023).

Ouass, A. et al. Efficient removal of chromium (III) ions from aqueous solutions using sodium polyacrylate hydrogel powder: Characterization, kinetics, and regeneration studies. Inorganic Chem. Commun. 166, 112601 (2024).

Nasiri, A., Malakootian, M. & Javid, N. Modelling and optimization of lead adsorption by CoFe2O4@ CMC@ HZSM-5 from aqueous solution using response surface methodology. Desalination Water Treat. 248, 134–148 (2022).

Velinov, N. et al. Characterization and application of wood-ZrO2 sorbent for simultaneous removal of chromium (III) and chromium (VI) from binary mixture. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 36, 373–385 (2021).

Almeida, J. C. et al. Chromium removal from contaminated waters using nanomaterials–a review. TRAC Trends Anal. Chem. 118, 277–291 (2019).

Seid, S. M. & Gonfa, G. Adsorption of Cr(V) from aqueous solution using eggshell-based Cobalt oxide- zinc oxide nano-composite. Environ. Challenges. 8, 100574 (2022).

Rajapaksha, A. U. et al. A systematic review on adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions: recent advances. Sci. Total Environ. 809, 152055 (2022).

Xing, X., Alharbi, N. S., Ren, X. & Chen, C. A comprehensive review on emerging natural and tailored materials for chromium-contaminated water treatment and environmental remediation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107325 (2022).

Akhtar, M. S., Ali, S. & Zaman, W. Innovative adsorbents for pollutant removal: exploring the latest research and applications. Molecules 29, 4317 (2024).

Das, K. P., Chauhan, P., Staudinger, U. & Satapathy, B. K. Sustainable adsorbent frameworks based on bio-resourced materials and biodegradable polymers in selective phosphate removal for waste-water remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 31691–31730 (2024).

Eniola, J. O., Sizirici, B., Fseha, Y., Shaheen, J. F. & Aboulella, A. M. Application of conventional and emerging low-cost adsorbents as sustainable materials for removal of contaminants from water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 88245–88271 (2023).

Senila, M. & Cadar, O. Composites based on natural zeolites and green materials for the immobilization of toxic elements in contaminated soils: A review. Materials 17, 5977 (2024).

Ghobara, M. M., Ghobara, M. M., Ghobara, M. M. & Mohamed, A. Diatomite in use: Nature, modifications, commercial applications and prospective trends. Diatoms: Fundamentals Applications 471–509 (2019).

Gürü, M., Venedik, D. & Murathan, A. Removal of trivalent chromium from water using low-cost natural diatomite. J. Hazard. Mater. 160, 318–323 (2008).

Shewatatek, S., Gonfa, G., Hailegiorgis, S. M. & Tessema, B. Adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution using sulfuric acid-treated diatomite. Results Chem. 15, 102205 (2025).

Du, Y., Wang, X., Wu, J., Qi, C. & Li, Y. (2018).

Abukhadra, M. R., Sayed, M. A., Rabie, A. M. & Ahmed, S. A. Surface decoration of diatomite by Ni/NiO nanoparticles as hybrid composite of enhanced adsorption properties for malachite green dye and hexavalent chromium. Colloids Surf., A. 577, 583–593 (2019).

Sathya, S., Ragul, V., Veeraraghavan, V. P., Singh, L. & Ahamed, M. N. An in vitro study on hexavalent chromium [Cr (VI)] remediation using iron oxide nanoparticles based beads. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. 14, 100333 (2020).

Wang, W. Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics study on the adsorption of cr (VI) and as (III) by diatomite-modified MnO2. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 43, 859–872 (2022).

Nguyen, L. H. et al. Treatment of hexavalent chromium contaminated wastewater using activated carbon derived from coconut shell loaded by silver nanoparticles: batch experiment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 230, 1–14 (2019).

Farooqi, Z. H., Akram, M. W., Begum, R., Wu, W. & Irfan, A. Inorganic nanoparticles for reduction of hexavalent chromium: physicochemical aspects. J. Hazard. Mater. 402, 123535 (2021).

Alyosef, H. A. et al. Effect of acid treatment on the chemical composition and the structure of Egyptian diatomite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 132, 17–25 (2014).

Xia, Y. et al. Synthesis and characterization of antimicrobial nanosilver/diatomite nanocomposites and its water treatment application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 396, 1760–1764 (2017).

Panáček, A. et al. Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial efficiency of Ag/PDDA-diatomite nanocomposite. Colloids Surf., B. 110, 191–198 (2013).

Chelladurai, S. J. S. et al. Optimization of process parameters using response surface methodology: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 37, 1301–1304 (2021).

Weldemariam, Y., Enke, D., Schneider, D. & Alemayehu, E. Thermochemical purification, technical properties, and characterization of Ethiopian diatomite from Adami-Tulu deposit. Chem. Afr. 2, 733–740 (2019).

Tajmiri, S., Hosseini, M. R. & Azimi, E. Combined photocatalytic-adsorptive removal of water contaminants using a biologically prepared CdS-diatomite nanocomposite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 258, 123913 (2021).

Sun, Z., Yang, X., Zhang, G., Zheng, S. & Frost, R. L. A novel method for purification of low grade diatomite powders in centrifugal fields. Int. J. Miner. Process. 125, 18–26 (2013).

Man, J., Gao, W., Yan, S., Liu, G. & Hao, H. Preparation of porous brick from diatomite and sugar filter mud at lower temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 1035–1042 (2017).

Puente-Urbina, A., Hollenbach, J., Céspedes-Camacho, I. F., Matysik, J. & Valle-Bourrouet, G. Effect of pretreatment temperature on the surface modification of diatomite with trimethylchlorosilane. J. Porous Mater. 23, 1439–1449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10934-016-0204-1 (2016).

Yuan, P. et al. Removal of hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] from aqueous solutions by the diatomite-supported/unsupported magnetite nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 173, 614–621 (2010).

AbuKhadra, M. R. et al. Evaluation of different forms of Egyptian diatomite for the removal of ammonium ions from lake qarun: A realistic study to avoid eutrophication. Environ. Pollut. 266, 115277 (2020).

Ewais, H. A. & Obaid, A. Y. Adsorption characteristics of toxic chromium (VI) from aqueous media onto nanosized silver nanoparticles-treated activated carbon. Sep. Sci. Technol. 54, 494–506 (2019).

Ashour, E. A. & Tony, M. A. Eco-friendly removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution using natural clay mineral: activation and modification effects. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 2042 (2020).

Khezami, L. & Capart, R. Removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution by activated carbons: kinetic and equilibrium studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 123, 223–231 (2005).

Kostić, M. et al. A new catalyst with the superior performance for treatment of water polluted by anthraquinone compounds. Bull. Mater. Sci. 44, 1–10 (2021).

Velinov, N. et al. The influence of various solvents’ Polarity in the synthesis of wood Biowaste sorbent: evaluation of dye sorption. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 13, 8139–8150 (2023).

Koujalagi, P. S., Divekar, S. V., Kulkarni, R. M. & Nagarale, R. K. Kinetics, thermodynamic, and adsorption studies on removal of chromium (VI) using Tulsion A-27 (MP) resin. Desalination Water Treat. 51, 3273–3283 (2013).

Tandon, R., Crisp, P., Ellis, J. & Baker, R. Effect of pH on chromium (VI) species in solution. Talanta 31, 227–228 (1984).

Lawal, J., Odebunmi, E. & Adekola, F. Adsorption of Fe, Pb, Zn and cr ions from aqueous solutions using natural, ammonium oxalate and sodium hydroxide modified kaolinite clay. Ife J. Sci. 22, 1–23 (2020).

El-Tawil, R. S. et al. Silver/quartz nanocomposite as an adsorbent for removal of mercury (II) ions from aqueous solutions. Heliyon 5, e02415 (2019).

Kostić, M. et al. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of a new material based on MgCoAl-LDH: characterization and optimization of sorption for progressive treatment of water. Environ. Technol. Innov. 26, 102358 (2022).

Peiravi-Rivash, O., Mashreghi, M., Baigenzhenov, O. & Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Producing bacterial nano-cellulose and keratin from wastes to synthesize keratin/cellulose nanobiocomposite for removal of dyes and heavy metal ions from waters and wastewaters. Colloids Surf., A. 656, 130355 (2023).

Bai, C., Wang, L. & Zhu, Z. Adsorption of cr (III) and Pb (II) by graphene oxide/alginate hydrogel membrane: Characterization, adsorption kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamics studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 147, 898–910 (2020).

Karce, H. E. et al. Efficient removal of methylene blue by a Biochar from Neem tree shell wastes using adsorption technology. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 15, 13559–13580 (2025).

Kostić, M. M. et al. Effects of ultrasound on removal of ranitidine hydrochloride from water by activated carbon based on lagenaria siceraria. Environ. Eng. Sci. 36, 237–248 (2019).

Choudhary, B. & Paul, D. Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics of hexavalent chromium removal using Biochar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 2335–2343 (2018).

Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. et al. Kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamic study of cr (VI) sorption into toluidine blue o-impregnated XAD-7 resin beads and its application for the treatment of wastewaters containing cr (VI). Chem. Eng. J. 160, 190–198 (2010).

Tran, H. N., You, S. J., Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. & Chao, H. P. Mistakes and inconsistencies regarding adsorption of contaminants from aqueous solutions: a critical review. Water Res. 120, 88–116 (2017).

Temkin, M. J. & Pyzhev, V. Recent modifications to Langmuir isotherms. (1940).

Wang, Y. et al. Guideline for modeling solid-liquid adsorption: Kinetics, isotherm, fixed bed, and thermodynamics. Chemosphere 349, 140736 (2024).

Azri, N. et al. Single and binary adsorption of Paracetamol and diclofenac onto Biochar produced from pepper stem: which adsorption properties change in the binary system? Colloids Surf., A. 694, 134136 (2024).

Sajjadi, S. A. et al. A novel route for Preparation of chemically activated carbon from pistachio wood for highly efficient Pb (II) sorption. J. Environ. Manage. 236, 34–44 (2019).

Pérez-Marín, A. et al. Removal of cadmium from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto orange waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 139, 122–131 (2007).

Alehegn, M. et al. Valorization of castor seed shell waste as lead adsorbent by treatment with hot phosphoric acid: optimization and evaluation of adsorption properties. Chemosphere 362, 142655 (2024).

Djekoune, L. et al. Phosphate adsorption on dried alum sludge: modeling and application to treatment of dairy effluents. Environ. Res. 252, 118976 (2024).

Masuku, M., Nure, J. F., Atagana, H. I., Hlongwa, N. & Nkambule, T. T. Pinecone Biochar for the adsorption of chromium (VI) from wastewater: Kinetics, thermodynamics, and adsorbent regeneration. Environ. Res. 258, 119423 (2024).

Fotsing, P. N. et al. Adsorption of cr (VI) and phosphate anions by amino-functionalized palm oil fibers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 60247–60259 (2024).

Surender, Mohan, C., Kumar, R. & Varma, R. S. Hybrid nanomaterials for efficient hexavalent chromium removal from waste water: activated charcoal sheet modification through polypyrrole and silver nanoparticles. Nanatechnol. Environ. Eng. 9, 347–358 (2024).

Tagesse, W. & Haile, B. Adsorptive removal of chromium (VI) using silver nanoparticles synthesized via green approach with the extract of Moringastenopetala. Orient. J. Chem. 37, 380 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Addis Ababa Science and Technology University, Ethiopia (IG 03/2022). Also, this research is supported by the Postdoc grant of Semnan University (Number 23630).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Girma Gonfa did Conceptualization, Methodology development, and Writing-reviewing and editing, Alem Kidanu did Data collection, Writing original draft, Sumia Akram and Basant Lal did Validation, Investigation, Writing-review and editing, Gulmira Kezembayeva and Dmitry Olegovich Bokov did Data curation, Software, and Writing-review and editing, Alireza Asghari did Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Krishna Kumar Yadav did Investigation, Formal analysis, Anbalagan Saravanan did Reviewing and editing, Ahmad Hosseini-Bandegharaei did Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonfa, G., Kidanu, A., Akram, S. et al. Adsorptive removal of Cr(VI) from water using silver nanoparticle modified-diatomite nanocomposite. Sci Rep 15, 41993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25998-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25998-y