Abstract

As anxiety levels continue to rise among college students, identifying effective mitigation strategies has become crucial. Given the limitations in accessibility and applicability of existing interventions, this study investigates whether early rising can serve as a simple and non-invasive intervention. Drawing on conservation of resources theory, the research examines the impact of early rising on self-efficacy and anxiety levels through a cross-sectional survey and a four-week field experiment conducted at a university campus in Beijing, China. The survey, which garnered 148 valid responses (23.65% male, 76.35% female; Mage = 19.75, SD = 0.95), revealed that despite a tendency towards late nights and late get-ups, students generally agree on the importance of early rising. The self-reported average number of early rising per week demonstrates a significant negative correlation with anxiety and a significant positive correlation with self-efficacy. Subsequently, the field experiment involved 158 undergraduate students (24.68% male, 75.32% female; Mage = 20.20, SD = 0.79) who neither had existing early-rising habits nor made a conscious effort to rise early. The result further confirmed that college students who rise early exhibit lower anxiety. Self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between early rising and anxiety reduction. The findings demonstrate that even minor adjustments to daily habits can lead to positive mental health outcomes. The study also offers practical insights for university mental health professionals and students alike, suggesting that promoting early rising could be a viable strategy for enhancing mental well-being on campus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In contemporary society, the transition from high school to university marks a significant life change, bringing with it numerous challenges1. These include academic pressures, social adjustments, and the pursuit of personal identity2,3. Anxiety among college students has emerged as a pervasive and concerning issue. Anxiety can have a negative impact on students’ overall well-being4,5. Understanding and mitigating anxiety in college students has become a critical focus for both researchers and educators.

Previous research has found that self-efficacy can play a pivotal role in influencing anxiety6,7. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully execute the behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments8,9. Individuals with high self-efficacy are more inclined to believe in their ability to cope with and solve problems when facing difficulties and stress. This positive mindset contributes to alleviating anxiety10,11. In contrast, those with low self-efficacy may experience heightened anxiety when confronted with similar situations12. Many studies have explored various approaches to improve self-efficacy, thereby alleviating anxiety in college students. These approaches range from cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, such as cognitive restructuring13 and relaxation training14, to experiential learning activities15, like group projects16 and leadership training17,18. While these interventions have shown some promise, they are not universally applicable or easily accessible to all students19,20,21. For instance, some students may be reluctant to participate in traditional therapy sessions due to the stigma associated with mental health issues22, or time constraints resulting from their busy academic and social schedules23,24,25,26. Therefore, there is a need to explore alternative, more accessible interventions.

It is evident that early rising is a simple and universally applicable behavioral adjustment that does not require specialized training or extensive resources. The conservation of resources theory states that time is a precious resource27. The reduction of personal resource storage can lead to pain and negative emotional outcomes, underscoring the importance of resource management28. Early rising is a lifestyle habit widely advocated by the public29,30. It can effectively increase an individual’s disposable time, providing ample opportunities for activity planning and execution31. By expanding the temporal window available for daily endeavors, early rising equips individuals with greater flexibility and control over their schedules. So, we believe that adopting the habit of early rising can contribute to an increase in college students’ self-efficacy. This, in turn, may lead to a reduction in anxiety as they feel more capable of managing their daily tasks and responsibilities.

This study aims to investigate whether early rising can serve as an effective practical intervention to enhance self-efficacy and reduce anxiety among college students. Theoretically, this study explores the impact of early rising—a non-invasive and easily understandable behavioral intervention—on self-efficacy and anxiety, thereby contributing to the existing literature on cost-effective, non-pharmacological interventions for mental health. Practically, this study can provide support for school administrators and mental health professionals to promote early rising among college students, thereby enhancing the mental health of a broader range of college students.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Early rising and anxiety among college students

The conservation of resources theory posits that individuals strive to obtain, retain, foster, and protect resources they value32. The threat of resource loss, or insufficient resource gain following resource investment, can lead to stress and anxiety33. College life is characterized by high demands and limited resources. Students frequently juggle multiple responsibilities, including coursework, extracurricular activities, part-time jobs, and social engagements, all of which compete for their limited time and energy34. Early rising, as a behavioral intervention, can mitigate anxiety among college students by enhancing their time resource reserves. Early rising directly extends an individual’s effective activity time35,36. This additional time serves as a buffer against the pressures of daily life, allowing students to approach their tasks with greater calmness and preparedness37,38,39.

In summary, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1

Early rising can reduce anxiety.

Early rising, self-efficacy, and anxiety

College life often accommodates a more flexible lifestyle compared to the structured routines of high school40. Its nature makes early rising a challenging endeavor for college students, for example, due to a delayed circadian rhythm or simply the temptation to stay in bed41. Through the experience of surmounting the obstacles associated with early rising, students reinforce their belief in their capabilities42,43. More importantly, early rising objectively provides individuals with additional time in the morning that is often free from the immediate demands of work, school, or family obligations. The ability to allocate time for self-directed activities reinforces the individual’s belief that they can manage their resources effectively44. When individuals feel that they have control over how they spend their time, they are more likely to view themselves as capable of handling other aspects of their lives45.

Early rising empowers individuals to take control of their immediate environment and daily schedule. This heightened sense of self-efficacy can subsequently have a salutary effect on anxiety levels46,47. When students possess a robust confidence in their ability to manage their daily routines, they are more inclined to perceive challenges from various aspects of university life, such as academic pressures, social interactions, and extracurricular commitments, as opportunities for personal growth rather than as insurmountable threats48,49. This shift in perspective effectively mitigates their anxiety. Thus, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2

Early rising can enhance self-efficacy, thereby positively affecting the reduction of anxiety.

Unlike general behavioral interventions, which are often implemented in relatively controlled or structured settings50,51,52, early rising is a self-initiated and self-regulated behavior that occurs within the context of daily life. While the sustainability of general behavioral interventions can be challenging53,54, early rising, once established as a habit, is more inclined to become a self-sustaining behavior. This underscores the potential of early rising as a more enduring and practical behavioral intervention. By addressing these research questions, we aim to present a novel approach to anxiety management based on specific behavioral interventions, offering practical insights for university mental health professionals and students.

Methods

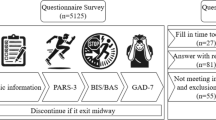

The research framework is depicted in Fig. 1. To test the two hypotheses, a cross-sectional survey and a four-week field experiment were conducted at a campus of a university in Beijing, China. Both studies targeted first- and second-year undergraduate students. This specific demographic group leads a relatively stable campus life with consistent academic demands (e.g., regular class schedules and similar assignments) and interpersonal circumstances (e.g., stable peer groups and routine social interactions). This stable environment enables us to isolate the effects of early rising behavior. Specifically, the cross-sectional survey aimed to gather data on college students’ lifestyles, psychologies, and other pertinent information, reflecting their actual living conditions. The field experiment employed a more rigorous experimental design to control for the interference of internal and external variables. By implementing an early rising habit development program, we explored the role of early rising in enhancing self-efficacy and reducing anxiety, providing empirical evidence for the verification of the hypotheses.

We confirm that all studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethical standards set by the academic committee of Business School, Central University of Finance and Economics. We adhered strictly to ethical standards and safeguarded respondents’ privacy by only identifying participants through their student codes. We clearly stated the purpose of data collection and the privacy protection measures in place. Participation in this study was voluntary, and the collected data were used solely for research purposes. We explicitly informed participants of their right to withdraw at any time.

Study 1: a cross-sectional survey on college students’ rising habits, and their associations with self-efficacy and anxiety

This survey aimed to understand the actual patterns of college students during their school days, by investigating key information such as their rising times and bedtime on weekdays over the past month. G*Power 3.1.955 was employed to calculate the required sample size. The results indicated that, with a desired power of 0.80 at a significance level of 0.05 and an effect size of 0.5, the appropriate sample size was 128. The survey was conducted over the period of September 29–30, 2019. A total of 160 questionnaires were randomly distributed through the university’s official online communication channels. Ultimately, 148 valid responses were obtained, yielding a response rate of 92.5%. The gender distribution among the respondents was 23.65% male and 76.35% female, with a mean age of 19.7 years (SD = 0.95). We compared the gender ratio of the collected sample in this study with the gender proportions of the student body in the past five years at this university, and it can be concluded that the gender ratio of the sample is reasonable.

Questionnaire design

To measure the weekly number of early rising, we adopted a single-item approach, drawing on methods used for assessing behavioral frequency by scholars such as Boateng et al.56 and Robbins et al.57. Our procedure involved two steps to account for individual differences in the definition of “early rising”. First, we established a personalized benchmark by asking participants, “What time do you consider as beneficial rising?” Subsequently, we assessed their frequency relative to this standard with the question, “How many times did you truly rise at this time per week?” This method avoids imposing a uniform standard and respects individual variations in daily routines. For measuring self-efficacy and anxiety, we adopted well-validated scales from previous research. Specifically, self-efficacy was measured using Schwarzer’s 10-item scale58 (5-point Likert, 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), which was translated and revised by Wang et al.59. Anxiety was measured using Spielberger’s 20-item scale60(5-point Likert scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), which was translated and revised by Li and Qian61. Both scales are widely used in the research on Chinese students’ psychology.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement scales, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) on the anxiety and self-efficacy scales using Mplus 8.3. The main results are as follows (see Tables 1 and 2): The Cronbach’s α for both the anxiety and self-efficacy scales were above 0.8, indicating good internal consistency. All item factor loadings were significant (p < 0.001) and exceeded the threshold of 0.4. The composite reliability (CR) for both constructs was high (Self-Efficacy CR = 0.891; Anxiety CR = 0.915), surpassing the recommended value of 0.762. Discriminant validity was established according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion63. The average variance extracted (AVE) for each of the two latent variables was greater than the squared correlation between them. This confirms that anxiety and self-efficacy are distinct constructs with good discriminant validity in our sample.

Results analysis

Going to bed and rising in the morning

As illustrated in Fig. 2, students’ rising times on weekdays exhibit a certain distribution pattern. Specifically, only 23 students (15.54%) rose at or before 7:00 AM. 46 students (31.08%) between 7:00 and 8:00 AM, and 76 students (51.35%) between 8:00 and 10:00 AM, totaling 122 students (82.43%). Most students tend to rise later, even on weekdays. Additionally, three students usually rise after 10:00 AM, further highlighting the irregular sleep–wake patterns of some students. Figure 3 reveals that only a handful of students (6.08%) go to bed at or before 11:00 PM, and similarly, a few students (6.08%) sleep after 2:00 AM. Students predominantly go to bed around midnight. This phenomenon may be associated with the prevalent habit of staying up late in modern lifestyles. Figure 4 presents the duration of students’ nocturnal rest (rising time minus sleep time). 68.92% of students manage to obtain 7 h or more of nocturnal rest. This duration is generally considered the ideal range for adults to maintain good physiological function and mental health64,65. This suggests that, despite irregular patterns, students are, to some extent, attempting to balance their lifestyles by ensuring sufficient sleep duration.

Beneficial rising times

Although only 15.54% of students rise at 7:00 AM or earlier, a remarkable 70.95% of students perceive rising at 7:00 AM as beneficial. This observation reveals a significant discrepancy between the perceived benefits of early rising and actual behavior among college students.

The relationship among the number of early risings within a week, anxiety, and self-efficacy

With the self-reported average number of early rising per week serving as the independent variable, and anxiety and self-efficacy as the dependent variables, respectively, the linear regression analysis results indicated a significant negative correlation between the frequency of early rising and students’ anxiety levels (β = − 0.07, t = − 2.96, p < 0.01), and a significant positive correlation with self-efficacy (β = 0.05, t = 2.22, p < 0.01). The model was further analyzed using structural equation modeling. The model fitting was assessed using multiple indicators, including χ2/df = 2.264, CFI = 0.7286, TLI = 0.707, IFI = 0.732, and RMSEA = 0.093. The results (see Fig. 5) revealed that the number of early rising per week had a direct negative predictive effect on anxiety, with a predictive effect of − 0.293 (p < 0.001). The number of early risings also had a direct positive predictive effect on self-efficacy, with a predictive effect of 0.195 (p < 0.05). Moreover, self-efficacy had a direct negative predictive effect on anxiety, with a predictive effect of − 0.326 (p = 0.002).

Discussion

First, the aforementioned regression results suggest that as the average number of early risings per week increases, students’ anxiety levels exhibit a tendency to decrease, and students who rise early more frequently tend to possess higher levels of self-efficacy. Although these relationships are statistically significant, it is crucial to note that the questionnaire survey employed was cross-sectional in design. This design characteristic precludes the establishment of direct causality. Moreover, since the frequency of early risings in the survey could only be reported by the students themselves, it also renders the measurement of this variable prone to biases, such as recall bias or social desirability bias. Consequently, relying solely on the survey data, we are unable to conclude that early rising habits serve as the direct cause of these positive psychological outcomes.

Furthermore, by examining the confirmatory factor analysis indicators of the structural equation modeling, we observed that despite χ2/df being less than 3, which indicates a relatively good model fit, the values of CFI, TLI, IFI, and RMSEA all fall within a moderate range. When considered comprehensively, the model’s fitting performance is not entirely satisfactory. This observation also implies that more rigorous experimental controls are necessary to overcome the limitations inherent in the cross-sectional design and the self-reported nature of early rising frequency. By doing so, we can gain deeper insights into the potential mechanisms underlying the relationships between early rising, anxiety, and self-efficacy. Therefore, we conducted a four-week field experiment.

Building upon the results of the questionnaire survey, we found that college students on the research campus generally agreed that 7:00 AM is a beneficial time for early rising; however, the proportion of students who rise at or before this time was relatively low. Considering this, we designed an early-rising habit development program to explore the specific impact of early rising on reducing anxiety among students who did not have preexisting early-rising habits. The main reasons for focusing on students without preexisting early-rising habits lie in several aspects. Firstly, it allows us to isolate the effect of early rising more effectively. Students who already have a habit of early rising may have other factors at play that influence their anxiety levels, such as long-standing lifestyle routines or personality traits that predispose them to both early rising and lower anxiety. By selecting students without this habit, we can minimize the confounding variables and more accurately attribute any changes in anxiety levels to the early-rising habit development program. Secondly, this approach provides a clearer baseline for comparison. Students without preexisting early-rising habits start from a similar point in terms of their daily routines and sleep patterns related to early rising. This enables us to observe the gradual transformation and its impact on anxiety as they develop the early-rising habit over the four weeks. In contrast, students who already rise early may have already reached a certain level of adaptation and stability in their routines, making it difficult to detect significant changes in anxiety. Lastly, targeting students who do not have early rising habits holds practical significance for promoting healthy lifestyles on campus. If the program is proven effective in reducing anxiety within this group, it could potentially have a positive impact on improving the mental health of a broader spectrum of college students.

Study 2: a four-week field experiment investigating the impact of early rising on college students’ anxiety and the mediating role of self-efficacy

This experiment openly recruited 200 participants from the same campus between October 1st and 7th, 2019. When participants filled out the application questionnaire for participation, we verified that they had not engaged in any other behavioral intervention activities currently or in the past year. During the registration phase, we utilized the dormitory access card-swiping data. We specifically focused on the number of times students exited the dormitory during early-morning hours (before 7:00 AM) in the preceding month. We found that 167 participants (24.55% male, 75.45% female; Mage = 20.17, SD = 0.79) had exited the dormitory 2 times or fewer. We identified that these participants neither had existing early rising habits nor consciously made an effort to wake up early. Consequently, they were enrolled in the program. These participants committed to abstaining from any external activities that could potentially disrupt their early-rising behavior throughout the four-week experimental period, which ran from October 14th to November 10th, 2019, apart from their regular academic and daily life activities.

The choice of this period offers significant advantages for experimental condition control. At this stage, students have generally settled into their academic routines, with course schedules, extracurricular activities, and social engagements reaching a relatively stable state. This stability reduces the likelihood of unexpected disruptions that could affect their early-rising behavior. For instance, there are fewer major academic deadlines, such as mid-term exams or large-scale project submissions, which might otherwise cause students to alter their sleep patterns. Moreover, social events like freshman orientation or campus-wide festivals, which can disrupt normal routines, are less likely to occur during this period. By minimizing these external factors that could influence early rising, we can more accurately attribute any changes in participants’ early-rising habits and anxiety levels to the intervention of the early-rising habit development program, thus enhancing the internal validity of the experiment.

Experiment design

During a four-week period, participants were required to complete early rising sign-ins for at least five days per week (i.e., early rising at least five times per week). Qualified participants received a reward of 25 yuan (approximately equivalent to 3.4 US dollars), serving as positive feedback and motivation for their early rising behavior. Therefore, participants who completed the four-week early rising task received a total reward of 100 yuan. The reward was scheduled after the conclusion of the four-week experiment, intended to minimize the potential interference of immediate financial incentives on participants’ psychologies, ensuring the validity of the experiment results. To ensure that the experiment did not adversely affect participants’ nighttime rest duration, we reminded participants to ensure their normal sleep time.

To ensure the genuine fulfillment of participants’ early-rising behavior, we required them to clock in at designated spots in the dining hall. The clock-in records thus obtained served as an effective means of monitoring their early-rising behavior. We considered participants’ actual commuting time from dormitories to the dining hall (measured at an average of 5 minutes) and set the daily clock-in time window from 7:00 AM to 7:10 AM. This can balance practical feasibility and ensure participants have sufficient time to complete the sign-in process.

Experiment procedures

Before the experiment officially started, we conducted pretests on participants’ self-efficacy (Cronbach’s α = 0.887) and anxiety (Cronbach’s α = 0.919) to obtain baseline data. On the day after the end of the experiment, participants were again asked to complete the self-efficacy scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.902) and anxiety scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.942) to assess changes in their psychologies after the experiment.

Within a week after the experiment, we distributed the rewards to participants. We interviewed participants with fewer early rising instances. Among them, 9 participants reported being away from campus for multiple nights during the experiment, effectively constituting per-experimental withdrawal. Considering this practical situation, we adjusted the sample included in the final statistical analysis of the experiment results, determining the effective sample size to be 158 (24.68% male, 75.32% female; Mage = 20.20, SD = 0.79).

Results analysis

Number of early risings within four weeks

We conducted an in-depth observation of the behavioral performance of 158 participants in a four-week early rising experiment (see Fig. 6). 74 participants engaged in early rising 20 times or more, accounting for 46.84% of the total. This data indicates that cultivating an early rising habit is feasible and sustainable for a significant portion of the student population who previously lacked such a habit. However, the data also reveals significant individual differences in early rising behavior. Specifically, 25 participants engaged in early rising fewer than five times; although this proportion is not high, it includes 8 participants who did not rise early at all. The performance underscores the challenges associated with developing an early rising habit.

Psychological comparison before and after early rising

The results of the paired t-test indicate that the anxiety of the 158 participants after engaging in the early rising experiment was significantly lower compared to their pre-experiment levels (Mpre-experiment = 2.39, SD = 0.60, Mpost-experiment = 1.96, SD = 0.61; t = 7.74, p < 0.001). Similarly, there was a notable difference in self-efficacy before and after the experiment (Mpre-experiment = 3.40, SD = 0.50, Mpost-experiment = 3.48, SD = 0.56; t = − 2.24, p < 0.05), with participants experiencing a positive increase in self-efficacy following the four-week early rising intervention.

Mediation effect test

We explored the mechanism of self-efficacy as a mediating variable. Using post-experiment anxiety as the dependent variable, the number of early rising as the independent variable, and post-experiment self-efficacy as the mediator, with gender, age, pre-experiment anxiety, and pre-experiment self-efficacy as control variables in Model 4 of the PROCESS program66. The results showed that the number of early rising positively affected self-efficacy (β = 0.02, p = 0.001), and an increase in self-efficacy significantly reduced anxiety (β = − 0.28, p = 0.003). The total effect of the number of early risings on anxiety was − 0.03 and significant (95% CI − 0.04, − 0.02). When controlling for self-efficacy, the direct effect remained significant (95% CI − 0.04, − 0.01), but the effect size decreased to − 0.026. Through the mediating role of self-efficacy, the indirect effect of the number of early risings on anxiety was − 0.005 (95% CI − 0.01, − 0.001), indicating that self-efficacy partially mediated this relationship, thus validating Hypothesis 2.

Robustness check

To demonstrate the robustness of the results, we conducted another mediation test. According to the early rising sign-in rules, engaging in early rising five times or more per week qualified as completing the weekly task. The number of weeks in which participants completed the task, to some extent, also reflect their early-rising behavior. The new independent variable was defined as “total weeks of task completion”. Using post-experiment anxiety as the dependent variable, and the post-experiment self-efficacy as the mediator, with gender, age, pre-experiment anxiety, and pre-experiment self-efficacy as control variables in Model 4 of the PROCESS program. The results showed that early rising completion weeks had a significant positive impact on self-efficacy (β = 0.08, p = 0.001), and an increase in self-efficacy significantly reduced anxiety (β = − 0.29, p = 0.003). Overall, the total effect of the total weeks of early rising task completion on anxiety was − 0.14, which was statistically significant (95% CI − 0.20, − 0.08). When controlling for self-efficacy, although the direct effect of total weeks of early rising task completion on anxiety remained significant (95% CI − 0.18, − 0.06), its effect size decreased to − 0.12. The indirect effect of self-efficacy on this relationship was − 0.02 (95% CI − 0.05, − 0.004). Self-efficacy still played a partial mediating role. The results of this robustness check further supported our research conclusions.

Discussion

The aim of Study 2, conducted as a field experiment, was to minimize the interference of external factors and intrinsic motivations related to spontaneous early rising, thereby allowing a more controlled investigation into whether early rising can effectively intervene in anxiety levels among individuals. By selecting a stable period in the semester and recruiting participants who neither had preexisting early-rising habits nor were subject to external disruptions, we were able to establish a more causally valid environment. The mediation mechanism tests confirmed our hypothesis that early rising can enhance self-efficacy, thereby positively affecting the reduction of anxiety. In addition, an encouraging revelation came from the interviews with participants after the experiment. The interviews revealed that advancing their rising time did not significantly impact their nighttime rest. This provides encouragement for college students who stay up late and rise late, giving them more confidence and willingness to adopt new early rising habits and promote their mental health67.

Although these findings aim to provide support for our inferences, the experiment solely involved recording participants’ early rising behavior without continuously monitoring anxiety and self-efficacy through questionnaires during the experimental period. This lack of real-time monitoring may have limitations, as we were unable to capture the immediate and dynamic changes in psychological states associated with early rising behavior. However, we chose not to implement additional interventions or frequent assessments that could have disrupted participants’ natural routines and introduced other confounding variables. We believed that maintaining the ecological validity of the experiment was paramount, ensuring that the observed effects were as close to real-world conditions as possible. Moreover, we must acknowledge that in our quasi-experimental design, the absence of random assignment of participants to treatment and control groups introduces the risk of systematic differences between cohorts. These unmeasured and potentially confounding variables may create selection bias, thereby compromising the internal validity of our causal inferences. This limitation reflects a fundamental challenge inherent in non-randomized intervention studies.

General discussion

Main findings

Anxiety has emerged as an increasingly prominent mental health issue for young people68. Unlike general behavioral interventions, which are often implemented in relatively controlled or structured environments, we believe that early rising holds potential as a more simple and practical behavioral intervention. Drawing on conservation of resources theory, the study, through a cross-sectional survey and a four-week field experiment, investigated the impact of early rising behavior on anxiety among college students and validated the mediating role of self-efficacy. Before data analysis, we compared the gender ratio of our sample with the university’s historical data to ensure its representativeness. The cross-sectional survey indicated a significant negative correlation between the self-reported average number of early rising per week and anxiety levels, and a significant positive correlation with self-efficacy. The four-week field experiment focuses more on reducing the interference of internal and external factors on the research conclusions. We recruited participants who neither had existing early-rising habits nor made a conscious effort to wake up early. The results further confirmed our hypotheses. We found that college students who rose early exhibited lower anxiety levels and higher self-efficacy. The mediation analysis revealed that self-efficacy partially mediated the relationship between early rising and anxiety reduction.

Theoretical and practical implications

In terms of theoretical contributions, our study focuses on early rising, a straightforward and non-intrusive adjustment to daily routines, which serves as an innovative behavioral intervention tool. Combining a cross-sectional survey and a four-week field experiment, we validate the effectiveness of early rising. This enriches the theoretical understanding of how specific behavioral interventions, within the context of conservation of resources theory, can influence mental health outcomes. One of the key theoretical advancements of our study is that it shows that a simple behavioral change, like early rising can also be an effective means of enhancing self-efficacy and alleviating anxiety. Moreover, the early rising behavior is non-invasive and highly accessible. It does not require any medical intervention, special equipment, or significant financial investment. Students can also implement it themselves. Our study adds evidence to the literature on low-cost, non-pharmacological interventions for mental health by demonstrating the efficacy of early rising as a behavioral adjustment. This is particularly important in the context of student mental health, where resources may be limited, and there is a need for easily implementable solutions.

At the practical level, this study provides actionable guidance for both college students and higher education institutions. It is crucial to note that while our findings support the potential well-being benefits of early rising, we emphasize that policy recommendations must be implemented with contextual sensitivity and individual adaptability. For example, students aiming to achieve a better psychological state can take the initiative to set a reasonable early-rising time according to their daily schedules. Additionally, they can seek peer support by forming small groups to hold each other accountable for rising early. This peer-based mechanism could cultivate a positive social environment that is conducive to the development of early rising habits. As for higher education institutions, they play a crucial role in promoting early-rising habits among students. In terms of practical implementation, offering half-price breakfasts can be a highly feasible incentive scheme to encourage early rising among students. In recent years, numerous Chinese higher education institutions have adopted the half-price breakfast model. Typically, universities set a specific time window in the early morning, such as from 6:30 AM to 7:15 AM. During this period, students who visit the campus dining hall can purchase breakfast items at a significantly reduced price, often half of the regular cost. This not only provides a financial incentive for students to rise early but also encourages them to start their day with a nutritious meal, which is beneficial for both physical and mental well-being. This flexible time window allows students with diverse class schedules to participate, minimizing the negative impact of class scheduling conflicts on their learning. Additionally, organizing extracurricular activities in the early morning hours, such as sports clubs or study groups, can provide additional motivation for students to wake up early and participate in positive social and academic interactions. To ensure the smooth implementation of early-rising initiatives, higher education institutions should align them with existing mental health services and educational policies. For example, mental health workshops can share the mental health benefits of early rising and offer practical tips for students to form and keep the habit. Lastly, we urge policymakers to prioritize evidence-based scalability. Pilot programs should incorporate rigorous evaluation designs (e.g., randomized controlled trials) to assess long-term adherence, unintended consequences (e.g., sleep deprivation), and cost-effectiveness relative to alternative interventions.

Limitations and future directions

While the present study has made contributions to elucidating the relationships among early rising, self-efficacy, and anxiety, it is crucial to acknowledge several limitations that warrant further investigation. These limitations, however, also point to promising avenues for future research to enhance the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

Firstly, the sample for this study was drawn from a single university in Beijing, China. Although this provided a well-defined and manageable research context, the geographical and institutional specificity inherently limits the generalizability of the results. For instance, due to the notable gender ratio characteristics of the student body at this university (e.g., a relatively higher proportion of female students), the sample may not fully represent the broader college student population in terms of gender distribution, potentially introducing bias when generalizing the findings to other contexts with different demographic compositions. In addition, the moderate sample size, although sufficient for the current study’s analyses, may not capture the full range of variability present in the larger college student population. Larger samples could potentially reveal more nuanced relationships and patterns. Future research endeavors should strive to diversify the sample by including college students from a wide range of geographical locations, cultural backgrounds, educational institutions, and demographic strata. Such an expansion would not only bolster the external validity of the findings but also furnish a more holistic understanding of how these relationships manifest across diverse settings.

Secondly, although our analysis has identified the important relationship between early rising, self-efficacy, and anxiety, further exploration of the psychological processes that support these observations is still needed. Longitudinal research designs incorporating more frequent psychological assessments could be employed to capture the dynamic fluctuations in psychological states associated with early rising behavior. This approach would facilitate a more nuanced comprehension of the processes at work, enabling researchers to delve deeper into the mediating effects and potentially uncover underlying mechanisms that were not fully elucidated in the current study.

Moreover, although efforts were made to control for extraneous variables and ensure ecological validity through the quasi-experimental design employed, the absence of random assignment to treatment and control groups does introduce certain internal validity concerns. Future research should consider implementing randomized controlled trials to more rigorously test the hypothesized relationships. Random assignment would enhance the internal validity of the findings, thereby providing more compelling evidence for causal claims and further solidifying the theoretical foundations of the research. When interpreting the potential effects of early rising on self-efficacy and anxiety, one possible alternative explanation is the placebo effect. Students may believe that early rising will reduce their anxiety and enhance their self-efficacy, and this belief alone may lead to improvements in their mental health. This highlights the need for future research to carefully design studies to rule out such alternative explanations. For example, in randomized controlled trials, a control group that receives a placebo intervention (e.g., a fake early-rising program with no real behavioral change) could be included to compare the effects with the actual early-rising group.

Additionally, while the monetary incentives utilized in this study were designed to minimize interference with participants’ natural routines, it is recognized that they may have influenced compliance outcomes to some degree. Future research could explore alternative incentive structures or methodologies that sustain participant motivation without compromising the integrity of the data.

Furthermore, the four-week duration of the intervention, while sufficient to demonstrate significant changes, raises questions regarding the sustainability of the observed behavioral and psychological effects. Future studies should contemplate extending the duration of the intervention and incorporating follow-up assessments to evaluate the persistence of these effects over time. This would provide invaluable insights into the long-term viability of early rising as a strategy for enhancing self-efficacy and reducing anxiety, thereby offering more pragmatic guidance for the development of mental health interventions and education programs.

Lastly, while self-reported measures were appropriate for addressing the research questions posed and are commonly employed in psychological research, they do introduce the potential for measurement bias. Future research could complement self-reported data with objective measures or multi-method assessments, such as physiological indicators or behavioral observations. This would augment the validity and reliability of the findings, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships under investigation and reinforcing the empirical basis of the research.

By addressing these considerations in future research, we believe this will not only contribute to the academic literature but also provide more robust and generalizable evidence for the development of effective mental health interventions and education programs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to limitations of university policy and anonymity of the questionnaire we conducted, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mastrokoukou, S. et al. Resilience and psychological distress in the transition to university: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Curr. Psychol. 43(28), 23675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06138-7 (2024).

Britton, B. K. & Tesser, A. Effects of Time-Management Practices on College Grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 83, 405. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.83.3.405 (1991).

Rathee, R. A comparative study of anxiety and academic achievement among adolescents. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 14, 97–100 (2023).

Jin, Y. et al. Smartphone distraction and academic anxiety: The mediating role of academic procrastination and the moderating role of time management disposition. Behav. Sci. 14, 820. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090820 (2024).

Misra, R. & McKean, M. College students’ academic stress and its relation to their anxiety, time management, and leisure satisfaction. Am. J. Health Stud. 16, 41 (2000).

Zuo, S., Huang, Q. & Qi, C. The relationship between cognitive activation and mathematics achievement: Mediating roles of self-efficacy and mathematics anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 43, 30794–30805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06700-3 (2024).

Sharma, P. K. & Kumra, R. Relationship between mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress: mediating role of self-efficacy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 186, 111363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111363 (2022).

Florescu, M. C. et al. Self-efficacy, anxiety, positive affect, and students’ expected grades in the context of the bachelor exam. Rom. J. Multidimens. Educ. 16, 550–568. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/16.2/871 (2024).

Yang, Y. Y. & Delgado, M. R. The integration of self-efficacy and response-efficacy in decision making. Sci. Rep. 15, 1789. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85577-z (2025).

Jia, J. et al. Effect of academic self-efficacy on test anxiety of higher vocational college students: The chain mediating effect. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 2417–2424. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S413382 (2023).

Liu, A. et al. The relationships between self-esteem, self-efficacy, and test anxiety: A cross-lagged study. Stress Health 40, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3346 (2024).

Bagnall, C. L., James, L. A. & Skipper, Y. ‘I shouldn’t really be here’: University students’ perceptions and experiences of transitioning to university with a contextual offer admission. High. Educ. Q. 79(2), e70003. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.70003 (2025).

Abdi, R. & Esmaealzadeh, S. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on psychological well-being and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in patients with depressive disorder. J. Res. Psychopathol. 3(8), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.22098/jrp.2022.10374.1069 (2022).

Karakus, A., Uzelpasaci, E. & Akyurek, G. The comparative effectiveness of progressive relaxation training on pain characteristics, attack frequency, activity self-efficacy, and pain-related disability in women with episodic tension-type headache and migraine. PLoS ONE 20(4), e0320575. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0320575 (2025).

Varman, S. D. et al. The effect of experiential learning interventions on physical activity outcomes in children: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 18(11), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0294987 (2023).

Hanham, J., Mccormick, J. & Hendry, A. Project-based learning groups of friends and acquaintances: The role of efficacy beliefs. J. Educ. Res. 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2020.1756729 (2020).

Jardine, H. Academic peer mentorship as a leadership development experience: Fostering leadership self-efficacy. J. Leadersh. Educ. 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.12806/v21/i1/r1 (2022).

Coluccio, G., Adriasola, E. & Escobar, E. Leadership development in women STEM students: The interplay of task behaviors, self-efficacy, and university training. Behav. Sci. 14(11), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14111087 (2024).

Wong, N. E., Hagan, M. J., Holley, S. R., Paik, J. H. & Duh, S. Traumatic stress, mental health stigma, and treatment-seeking attitudes among Chinese college students. J. Coll. Stud. Ment. Health 38(1), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/87568225.2022.2145253 (2022).

Bennett, J., Kidger, J., Haworth, C., Linton, M. J. & Gunnell, D. Student mental health support: A qualitative evaluation of new well-being services at a UK university. J. Further High. Educ. 48(4), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2024.2335379 (2024).

Moghimi, E. et al. Mental health challenges, treatment experiences, and care needs of post-secondary students: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 23(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15452-x (2023).

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G. & Haake, S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 53(3), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.325 (2006).

Bembenutty, H. Academic delay of gratification, self-efficacy, and time management among academically unprepared college students. Psychol. Rep. 104, 613–623. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.104.2.613-623 (2009).

Wan, M. et al. Working college students’ time pressure and work-school conflict: Do boundary permeability and dispositional mindfulness matter?. Psychol. Rep. 125, 3100–3125. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211029621 (2022).

McCune, M. Life 101: Time management: These two time management strategies are easy for college students to use and can generate big payoffs. Educ. Horiz. 93, 29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013175X15570861 (2015).

Kelly, A., Cuccolo, K. & Clinton-Lisell, V. Using instructor-implemented interventions to improve college-student time management. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 22(3), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v22i3.32378 (2022).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513 (1989).

Zeidner, M., Ben-Zur, H. & Reshef-Weil, S. Vicarious life threat: An experimental test of conservation of resources (COR) theory. Pers. Individ. Differ. 50(5), 641–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.035 (2011).

BaHammam, A. S. & Pirzada, A. Timing matters: The interplay between early mealtime, circadian rhythms, gene expression, circadian hormones, and metabolism—A narrative review. Clocks Sleep 5, 507–535. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep5030034 (2023).

Gorgol, J., Łowicki, P. & Stolarski, M. Godless owls, devout larks: Religiosity and conscientiousness are associated with morning preference and (partly) explain its effects on life satisfaction. PLoS ONE 18, e0284787. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284787 (2023).

Matsumoto, Y. et al. Clarifying the factors affecting the implementation of the “early to bed, early to rise, and don’t forget your breakfast” campaign aimed at adolescents in Japan. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 19, 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-021-00321-0 (2021).

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C. & Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manage. 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130 (2014).

Dong, R., Hu, J., Wu, H., Ji, R. & Ni, S. How techno-invasion leads to time banditry: A perspective from conservation of resources theory. Curr. Psychol. 43(46), 35340–35352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-07039-5 (2024).

Ansari, S. & Iqbal, N. Association of stress and resilience in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 236, 113006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.113006 (2025).

Zhang, F. et al. The effect of time management training on time management and anxiety among nursing undergraduates. Psychol. Health Med. 26, 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1778751 (2021).

Fan, J. et al. The mediating role of ego depletion in the relationship between state anxiety and academic procrastination among university students. Sci. Rep. 14, 15568. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66293-6 (2024).

MacCann, C., Fogarty, G. J. & Roberts, R. D. Strategies for success in education: Time management is more important for part-time than full-time community college students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 618–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.09.015 (2012).

Panek, E. Left to their own devices: College students’ “guilty pleasure” media use and time management. Commun. Res. 41, 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213499657 (2014).

Malkoc, S. A. & Tonietto, G. N. Activity versus outcome maximization in time management. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 26, 49–53 (2019).

Wengreen, H. J. & Moncur, C. Change in diet, physical activity, and body weight among young-adults during the transition from high school to college. Nutr. J. 8, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-8-32 (2009).

Hershner, S. D. & Chervin, R. D. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat. Sci. Sleep 6, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S62907 (2014).

Dimotakis, N., Mitchell, D. & Maurer, T. Positive and negative assessment center feedback in relation to development self-efficacy, feedback seeking, and promotion. J. Appl. Psychol. 102(11), 1514–1527. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000228 (2017).

He, J., Liu, Y., Ran, T. & Zhang, D. How students’ perception of feedback influences self-regulated learning: The mediating role of self-efficacy and goal orientation. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 38(4), 1551–1569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00654-5 (2023).

Alarcon, G., Edwards, J. & Menke, L. Student burnout and engagement: A test of the conservation of resources theory. J. Psychol. 145(3), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.555432 (2011).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2(1), 21-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00024 (1999).

Maddux, J. E., Norton, L. W. & Leary, M. R. Cognitive components of social anxiety: An investigation of the integration of self-presentation theory and self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 6(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1988.6.2.180 (1988).

Anderson, E. S., Winett, R. A. & Wojcik, J. R. Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 34(3), 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02874555 (2007).

Roick, J. & Ringeisen, T. Self-efficacy, test anxiety, and academic success: A longitudinal validation. Int. J. Educ. Res. 83, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.12.006 (2017).

Leppma, M. & Darrah, M. Self-efficacy, mindfulness, and self-compassion as predictors of math anxiety in undergraduate students. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 55(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020739x.2022.2054740 (2022).

Crosby, E. S., Troop-Gordon, W. & Witte, T. K. A pilot randomized-controlled trial of sleep scholar: A brief, internet-based insomnia intervention for college students. Behav. Ther. 56(2), 366-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2024.06.007 (2025).

Vidas, D., Nelson, N. L. & Dingle, G. A. Efficacy of the Tuned In music emotion regulation program in international university students. Psychol. Health 40(1), 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2023.2197007 (2025).

Rezvani, K. et al. Investigating the effect of peer-led educational intervention on behaviors related to pubertal health and its determinants in high school girls of Genaveh, Iran: Application of social cognitive theory. Arch. Pediatr. 31(8), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2024.05.001 (2024).

Neve, M. et al. Effectiveness of web-based interventions in achieving weight loss and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 11(4), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00646.x (2010).

Pico, M. L., Grunnet, L. G., Vinter, C. A., Aagaard-Hansen, J. & Kragelund Nielsen, K. Barriers and facilitators for sustainable weight loss in the pre-conception period among Danish women with overweight or obesity—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 23(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16676-7 (2023).

Faul, F. et al. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146 (2007).

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. & Young, S. L. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front. Public Health 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149 (2018).

Robbins, R. et al. Self-reported sleep duration and timing: A methodological review of event definitions, context, and timeframe of related questions. Sleep Health 7(6), 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2021.07.008 (2021).

Schwarzer, R. Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical approaches and a new model. Self-efficacy: Thought Control of Action, 217–243 (1992).

Wang, C. K., Hu, Z. F. & Liu, Y. Reliability and validity of the general self-efficacy scale. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 01, 37–40 (2001).

Spielberger, C. D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (Mind Garden, 1983).

Li, W. L. & Qian, M. Y. Revision of the state-trait anxiety inventory norm for Chinese college students. J. Peking Univ. Nat. Sci. 31(01), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.13209/j.0479-8023.1995.014 (1995).(In Chinese)

Straub, D., Boudreau, M. C. & Gefen, D. Validation guidelines for IS positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01324 (2004).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104 (1981).

Brooks, M. Night Owl or Lark? The Answer May Affect Cognition. Clin. Psychiatry News (2024).

Norbury, R. & Evans, S. Time to think: Subjective sleep quality, trait anxiety and university start time. Psychiatry Res. 271, 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.054 (2019).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Press, 2017).

Li, B. et al. Cross sectional associations of physical activity and sleep with mental health among Chinese university students. Sci. Rep. 14, 31614. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80034-9 (2024).

Iannattone, S. et al. Are anxiety, depression, and stress distinguishable in Italian adolescents? An examination through the depression anxiety stress scales-21. PLoS ONE 19, e0299229. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0299229 (2024).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 71972196

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, software, methodology, formal analysis, and visualization, X.L.; conceptualization, resources, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, and validation, J.L.; writing—original draft, X.L. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L., Y.L., S.X., and J.L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Academic Committee of Business School, Central University of Finance and Economics (protocol code EA20250005).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, X., Li, J., Li, Y. et al. Early rising as an intervention to alleviate anxiety and enhance self-efficacy among college students. Sci Rep 15, 41992 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26032-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26032-x