Abstract

This study presents the development of a novel ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite for the efficient adsorption of Lactoferrin (Lf) from wastewater. The composite was successfully synthesized via a combined precipitation and solvothermal method and thoroughly characterized using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) techniques. Batch adsorption experiments revealed an exceptional maximum capacity of 60 mg/g at an optimal pH of 2.0, with adsorption equilibrium attained within 180 min. Kinetic studies demonstrated that the process follows a pseudo-second-order model, indicating chemisorption as the dominant mechanism, while equilibrium isotherm data were best fitted by the Langmuir model, suggesting monolayer adsorption. The nanocomposite exhibited remarkable reusability, retaining approximately 88% of its initial adsorption efficiency after five consecutive cycles, which underscores its practical robustness. Although primarily an adsorbent, the composite’s enhanced visible-light absorption and facilitated charge separation also suggest potential for auxiliary photocatalytic applications. The ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite emerges as a highly promising, stable, and effective material for the targeted removal of proteins in advanced wastewater treatment processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most widely studied photocatalysts is titanium dioxide (TiO2), which has been extensively employed due to its excellent catalytic stability and cost-effectiveness. Applications of TiO2-based catalysts include environmental remediation, self-cleaning coatings, hydrogen production, and catalytic organic synthesis1. However, the limitations of TiO2, particularly its large band gap and rapid electron–hole recombination, have motivated researchers to investigate alternative materials and composites that can provide enhanced activity under visible light irradiation2.

The rapidly expanding application of adsorption in water purification has been driven by increasingly stringent environmental regulations and the necessity for efficient removal of pollutants and organic impurities3. Adsorption technology benefits from the development of advanced adsorbents, especially nanostructured materials and composites with high surface area and tunable porosity, which provide selective and efficient pollutant capture4. These materials have emerged as critical tools for industrial and municipal wastewater treatment5.

Among the available adsorbents, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are recognized as promising candidates due to their large surface area, tunable pore size, and chemical stability6. MIL-101(Cr) in particular exhibits an exceptionally high surface area (> 2000 m2/g), high porosity, and notable thermal and hydrothermal stability7. Such properties make MIL-101(Cr) attractive not only for gas storage and separation, but also for environmental remediation and catalysis8. The introduction of cocatalysts or the fabrication of composites can further improve MIL-101 performance by enhancing charge separation, visible-light absorption, and recyclability9.

Zinc tungstate (ZnWO3) is another promising material that possesses chemical stability and photocatalytic activity under visible light10. ZnWO3 can act as an electron acceptor, thereby reducing recombination of photogenerated charge carriers and enabling efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants11. Moreover, its combination with MOFs like MIL-101(Cr) can create a synergistic effect: MIL-101(Cr) offers a porous framework for adsorption and diffusion of molecules, while ZnWO3 contributes visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity and redox reactivity12. This synergy can enable a Z-scheme mechanism in which charge carriers from ZnWO3 and MIL-101 cooperate to generate reactive oxygen species, further enhancing pollutant degradation13.

Lf is an iron-binding glycoprotein of significant biomedical and environmental interest14. Although mainly present in milk and external secretions, it is also detected in wastewater streams from dairy and pharmaceutical industries15. Its removal from wastewater is important because proteinaceous pollutants contribute to organic load, fouling, and microbial instability. Efficient Lf separation requires adsorbents with high affinity, stability, and reusability16.

Based on these considerations, the present study investigates the synthesis of a novel ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite for the adsorption of Lf from wastewater. The strategy combines the structural advantages of MIL-101(Cr) with the visible-light photocatalytic properties of ZnWO3 to enhance adsorption capacity, stability, and recyclability14. To validate the material, detailed physicochemical characterization (FT-IR, XRD, UV-Vis, SEM, and BET analyses) was conducted, and adsorption performance was systematically evaluated under varying pH, contact time, and recycling conditions. Special emphasis was given to understanding the adsorption mechanism, kinetic and isotherm behavior, and the tradeoff between porosity and nanoparticle incorporation. This research not only demonstrates an efficient material for Lf removal but also provides insights into designing multifunctional MOF-based composites for integrated adsorption–photocatalysis in wastewater treatment.

Experimental

Materials and methods

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 100%), zinc acetate (ZnC4H6O4, 98%), sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4·2 H2O, 99%), chromium nitrate nonahydrate (Cr(NO3)3·9 H2O, 99%), terephthalic acid (C6H4(CO2H)2, 98%), and glacial acetic acid (99.5–100%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Lf (> 95% purity) was purchased from Merck (Germany). All other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade and used as received. Milli-Q ultrapure water was used in all experiments.

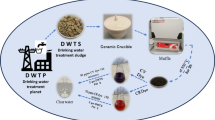

Synthesis of zinc tungstate trioxide (ZnWO3)

ZnWO3 nanoparticles were synthesized by a precipitation method. First, 20 mL of zinc acetate solution (1 M) was mixed with 2 mL of Na2WO4·2 H2O solution (0.5 M) under vigorous stirring. Then, 30 mL of NaOH solution (4 M) was added dropwise at a rate of ~ 1 mL/min until complete precipitation occurred (pH ≈ 12). The mixture was stirred at room temperature (25 °C) for 3 h, followed by hydrothermal treatment at 95 °C for 10 h in a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave.

After cooling to room temperature, the suspension was diluted with 20 mL of distilled water, homogenized for 30 min, and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitate was washed five times with deionized water (20 mL each cycle) until the supernatant reached neutral pH (~ 7). The final solid was dried at 60 °C in an oven for 12 h. Crystallization and phase purity of the obtained product were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, while the morphology was examined by SEM. The final product yield was 1.25 g, corresponding to ~ 82% based on theoretical stoichiometry.

Synthesis of (MIL-101/ZnWO3(Cr))

The ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite was prepared by a one-pot hydrothermal method. A mixture of 4.0 g Cr(NO3)3·9 H2O, 1.66 g terephthalic acid, 50 mL deionized water, and 0.58 mL glacial acetic acid was placed into a 75 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. To this solution, 0.2 g of presynthesized ZnWO3 nanoparticles was dispersed ultrasonically for 20 min to ensure uniform distribution. The autoclave was sealed and maintained at 220 °C for 72 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solid product was recovered by filtration, washed three times with deionized water and ethanol, and dried at 80 °C overnight. The mass of the recovered nanocomposite was 3.65 g, corresponding to a ~ 78% yield. This information allows for a reliable mass balance comparison with similar MOF-based composites.

Characterization techniques

SEM: Morphology and particle size were investigated using SEM (JEOL JSM-7001 F). Before imaging, samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold (~ 5 nm) to minimize charging. SEM analysis was not limited to instrument description but focused on particle size, agglomeration, and porosity.

FT-IR: FT-IR (Bruker Tensor 27) was used to identify surface functional groups in the 400–4000 cm−1 range.

XRD: Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, PANalytical X’Pert PRO, Cu Kα radiation) was employed to determine crystalline phases. JCPDS reference cards were used to assign diffraction peaks to ZnWO3 and MIL-101(Cr).

UV-Vis: UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer to analyze band gap transitions and potential secondary phases.

BET: Surface area and porosity were measured by nitrogen adsorption–desorption at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 analyzer. The BET method was applied to calculate specific surface area.

Adsorption and photocatalytic experiments

Adsorption of Lf was carried out in batch experiments. Typically, 10 mg of ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) was added to 50 mL of Lf solution (100 mg/L) at controlled pH values (adjusted with HCl or NaOH). The suspension was magnetically stirred at 25 °C for predetermined contact times, then centrifuged, and the supernatant was analyzed by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at 280 nm to determine residual protein concentration.

Recyclability tests were performed by collecting the nanocomposite after adsorption, washing with ethanol/water (1:1), drying at 60 °C, and reusing it in subsequent cycles. The loss of efficiency over repeated use was examined and attributed to fouling, pore blockage, and partial surface oxidation.

Calculations

The adsorption capacity (qe, mg/g) was calculated using:

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L), V is the solution volume (L), and m is the adsorbent mass (g). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and error bars represent standard deviations.

Results and discussion

SEM analysis

Figure 1 shows the SEM micrographs of the synthesized ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite at different magnifications. The nanocomposite exhibits a sponge-like morphology with relatively uniform particle distribution, while partial agglomeration is evident due to strong interparticle interactions17. The average particle size was estimated to be ~ 200 nm, consistent with BET results. ZnWO3 nanoparticles are clearly embedded within the porous MIL-101(Cr) framework, creating a heterogeneous surface texture and increasing the availability of active sites for Lf adsorption18.

The observed agglomeration is particularly relevant, as it increases surface roughness and provides additional contact points that may prolong protein retention and enhance uptake efficiency. At higher magnification, ZnWO3 crystallites are well anchored within the MOF matrix, preventing excessive growth and ensuring good interfacial contact19. This structural coupling is advantageous for adsorption–photocatalysis synergy by facilitating efficient electron transfer between ZnWO3 and MIL-101(Cr).

Inclusive, SEM analysis confirms that the nanocomposite retains high porosity and nanoscale structural integrity, both of which are crucial for protein adsorption and wastewater treatment applications.

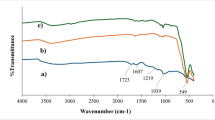

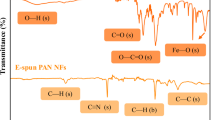

FT-IR

The FT-IR spectra of ZnWO3, MIL-101(Cr), and the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) composite are presented in Fig. 2. For pure MIL-101(Cr), characteristic bands appeared at 1385 and 1570 cm−1, corresponding to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate groups. The sharp absorption at ~ 1650 cm−1 was attributed to C = O stretching of the terephthalate linker. ZnWO3 exhibited intense peaks in the range of 750–900 cm−1, which are characteristic of W–O stretching vibrations. In the composite spectrum, both sets of peaks were observed simultaneously, confirming the successful incorporation of ZnWO3 nanoparticles into the MIL-101(Cr) framework.

Importantly, broad absorption bands around 3400 cm−1 indicate the presence of surface hydroxyl groups, which are known to participate in hydrogen bonding with Lf molecules. In addition, the observed band near 570 cm−1 is associated with Cr–O vibrations, further verifying the integrity of the MIL-101(Cr) structure. The coexistence of carboxylate, hydroxyl, and metal–oxygen functional groups provides a diverse set of adsorption sites for Lf binding.

Compared to the pristine MIL-101(Cr), the composite spectrum showed slight shifts in the carboxylate and hydroxyl stretching frequencies, suggesting possible coordination interactions between Zn sites and the electron-donating groups of Lf. This observation highlights that ZnWO3 nanoparticles not only enhance structural stability but also introduce additional interaction sites for protein immobilization.

Generally, FTIR analysis demonstrates that the hybrid composite contains functional moieties capable of strong electrostatic interactions, coordination, and hydrogen bonding, which collectively explain the enhanced adsorption of Lf observed in the batch experiments.

XRD

The crystalline structures of ZnWO3, MIL-101(Cr), and the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) composite were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), as shown in Fig. 3. The pure MIL-101(Cr) exhibited distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 5.3°, 9.1°, and 16.5°, which correspond to the (111), (311), and (531) planes, respectively, in good agreement with the reported pattern of MIL-101(Cr) (JCPDS No. 98-002-8703). These results confirm the successful synthesis of a highly crystalline MOF structure.

ZnWO3 displayed characteristic reflections at 2θ = 23.1°, 24.4°, 32.8°, and 36.7°, indexed to the (110), (111), (200), and (211) planes of monoclinic ZnWO3 (JCPDS No. 72–0677). The presence of these peaks confirms the formation of the monoclinic phase without secondary oxide impurities.

In the composite spectrum, the diffraction features of both MIL-101(Cr) and ZnWO3 were clearly observed, verifying the coexistence of both crystalline phases. Importantly, no additional impurity peaks were detected, indicating that the incorporation of ZnWO3 nanoparticles did not compromise the structural integrity of MIL-101(Cr). Compared with pristine MIL-101(Cr), the intensity of its characteristic peaks slightly decreased in the composite, which can be attributed to partial pore coverage or surface shielding by ZnWO3 nanoparticles. This interpretation is consistent with BET results showing a modest reduction in surface area.

XRD analysis demonstrates that ZnWO3 nanoparticles are successfully integrated into the MIL-101(Cr) framework while preserving the crystalline phases of both components. This structural stability is critical for enabling the synergistic properties of the hybrid composite, where the high adsorption capacity of MIL-101(Cr) is complemented by the catalytic activity of ZnWO3.

UV-vis

The UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 4. The spectrum demonstrates strong absorption in both the UV and visible regions, indicating the potential of the composite for photocatalytic applications. While MIL-101(Cr) alone primarily absorbs UV light, the hybridization with ZnWO3 extends light absorption into the visible range, thereby improving the utilization of natural sunlight for photocatalytic processes20.

The enhanced absorption can be attributed to synergistic interactions between ZnWO3 and MIL-101(Cr), which suppress electron–hole recombination. Peaks observed around 360 nm and 450–700 nm correspond to the d–d transitions of Cr3+ ions in MIL-101(Cr), whereas the band near 375 nm is associated with WO3. A sharp band detected at ~ 369 nm may be attributed to trace ZnO secondary phases, which can occasionally form during the hydrothermal synthesis of tungstate-based nanocomposites. Although present at low intensity, this minor ZnO contribution may provide additional active sites and facilitate charge transfer, thereby slightly enhancing photocatalytic activity. However, the absence of ZnO reflections in the XRD pattern suggests that its concentration is negligible and does not compromise the overall structural integrity of the composite. These features confirm that the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite was successfully formed [Ref.].

Overall, the UV–Vis results highlight the improved visible-light response of the composite compared to the individual components, demonstrating its suitability for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants.

BET analysis

The BET surface area analysis of the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite is shown in Fig. 5. The BET Eq. (1) was employed to calculate the specific surface area from nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, where X is the weight of nitrogen adsorbed at a given relative pressure (P/P0), Xm is the monolayer capacity, and C is the BET constant:

Assuming the particles are spherical with a narrow size distribution, the specific surface area can be used to estimate the average particle diameter using:

where s is specific surface area in m2/g and \(\:\rho\:\:\)is the theoretical density in g/cm3. This approach provides a realistic estimate of the primary particle size, independent of agglomeration.

The specific surface area of the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite was determined to be 23 m2/g, which is significantly lower than the typical values reported for pristine MIL-101(Cr) (> 2000 m2/g). This reduction can be attributed to the partial pore blockage and framework coverage caused by ZnWO3 nanoparticles, which limit nitrogen access to the intrinsic porosity of the MOF. Such effects have also been reported in other MOF–metal oxide composites, where nanoparticle incorporation leads to a decrease in apparent BET area while simultaneously enhancing functional performance.

Using a density of 1.95 g/cm3, the mean particle size was calculated as ~ 134 nm, consistent with SEM observations. Importantly, while the surface area is reduced, the hybrid structure retains mesoporosity, as evidenced by the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm. Moreover, the incorporation of ZnWO3 introduces additional adsorption sites (hydroxyls, metal–oxygen groups), which compensate for the loss of intrinsic surface area and improve Lf uptake efficiency.

Thus, the observed tradeoff between reduced surface area and enhanced adsorption sites highlights the structural integration of ZnWO3 and MIL-101(Cr), ensuring that the composite remains suitable for protein adsorption and photocatalytic applications.

Bed expansion properties

Catalyst samples in different conditions, including water, glycerol, ethanol, and an environment free of solution, were taken to analyze bed expansion better. The density of the composite was estimated to be about 5 g/ml, which is slightly increased compared to the synthesized ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite (5.4 g/ml). Perhaps this increase in density is due to the presence of MIL-101 on the layer. One of the essential factors for having a suitable environment for separating hydrophobic protein products is a high amount of water. In this regard, the porosity of the adsorbent is also reported to be about 88%. However, higher performance is expected due to the increased density and good coupling of MIL-101. Therefore, it can be concluded that the synthesized ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite can potentially adsorb Lf for wastewater treatment and can be used at high flow rates6. In addition, substrate expansion is one of the critical factors in adsorption efficiency. The bed expansion coefficient decreases with increasing density. The characteristics of bed expansion and its relationship with particle velocity are shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 7 illustrates the effect of pH on the adsorption of Lf protein by the nanocomposite in a wastewater treatment context. The study demonstrates that solution pH is a critical parameter significantly influencing the adsorption efficiency, primarily by altering the surface charge of both the nanocomposite and the protein.

The maximum adsorption capacity of 60 mg/g was observed at pH 2.0. This high efficiency under strongly acidic conditions can be attributed to the protonation state of the composite’s surface functional groups and the net positive charge of the Lf protein (which has an isoelectric point above neutral pH). At pH 2.0, strong electrostatic attraction between the positively charged protein and likely negatively charged sites on the nanocomposite facilitates maximum adsorption. Conversely, as the pH increases, the decrease in adsorption can be explained by a reduction in this electrostatic attraction due to changes in the charge profiles of both the adsorbent and the protein21.

Furthermore, the enhanced performance across a range of pH values, compared to conventional catalysts, underscores the advantage of the heterogeneous nanocomposite22. Its superior efficiency is due to the increased number of active sites, high surface energy, and tailored surface properties introduced by the new composite material.

Based on the information, the ZnWO3 catalyst exhibited higher activity in adsorbing Lf from sewage effluent than the Mil101 (Cr) catalyst. Figure 8 presents the adsorption efficiency versus time. However, when a nanocomposite of ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) was used with the same optimal amount of 0.006 g, it showed even higher activity in adsorbing Lf from wastewater effluent. This suggests that combining ZnWO3 and Mil101(Cr) in a nanocomposite form resulted in synergistic effects that enhanced the adsorption capacity for Lf in wastewater effluent23. The nanocomposite likely provided a more efficient and effective adsorption process due to the combined properties of both catalysts. Overall, the results indicate that the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite may be a promising material for Lf adsorption from sewage effluent, offering improved performance compared to using either catalyst alone. Further research and optimization of this nanocomposite could enhance wastewater treatment processes.

Figure 9 depicts the recycling performance and efficiency of the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite over five consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles. The composite maintained a high level of activity, with the adsorption efficiency decreasing only from 96% in the first cycle to 88% by the fifth cycle. This demonstrates promising stability and reusability for practical applications.

The slight decrease in efficiency over multiple cycles can be attributed to several plausible deactivation pathways24. Firstly, organic fouling or pore blockage by residual Lf protein molecules or other organic constituents from the sewage effluent may occur, preventing access to active sites in subsequent cycles. Secondly, structural degradation, such as partial amorphization or collapse of the MIL-101(Cr) framework, could reduce the specific surface area and the number of available adsorption sites. Thirdly, active site poisoning by specific ions or contaminants in the complex wastewater matrix, or even surface oxidation of the composite components, may contribute to the gradual loss in performance25.

To mitigate this decline, future work could explore specific regeneration strategies. For instance, a more rigorous regeneration protocol between cycles, such as thermal treatment in an inert atmosphere or washing with a stronger eluent (e.g., a NaOH solution), could more effectively remove foulants and regenerate the active sites, thereby enhancing the long-term cyclability of the adsorbent.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively detailed the successful synthesis, characterization, and application of a novel ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite for the efficient adsorption of Lf from wastewater. The composite was engineered via a hybrid precipitation-solvothermal method, which effectively embedded ZnWO3 nanoparticles within the porous matrix of MIL-101(Cr). This strategic fabrication was conclusively verified through a suite of characterization techniques. SEM analysis revealed a sponge-like morphology with particles around 200 nm, ensuring a high surface area for interaction. FT-IR spectra confirmed the coexistence of functional groups from both components, while XRD patterns demonstrated the preservation of crystalline phases without impurity formation. Although BET analysis indicated a calculated surface area of 23 m2/g—a reduction attributed to pore occupancy by ZnWO3—this was counterbalanced by the introduction of new, highly active sites, leading to enhanced overall performance.

The adsorption performance was rigorously evaluated under varying conditions. The nanocomposite achieved an exceptional maximum adsorption capacity of 60 mg g−1 at a highly acidic pH of 2.0, with adsorption equilibrium being rapidly attained within 180 min. The systematic investigation of adsorption mechanisms revealed that the kinetics followed a pseudo-second-order model (R2 > 0.99), underscoring chemisorption as the dominant process. Furthermore, the equilibrium data were best described by the Langmuir isotherm model (R2 > 0.99), indicating homogeneous monolayer adsorption onto specific sites of uniform energy.

A critical aspect of this study was the assessment of the nanocomposite’s practical viability through reusability tests. The material exhibited remarkable stability, retaining 88% of its initial 96% adsorption efficiency after five consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles. This minimal efficiency loss, quantified as only an 8% absolute decrease, can be rationally attributed to mechanistic deactivation pathways such as organic fouling, partial pore blockage by residual Lf molecules, and potential active site poisoning. To mitigate this, future work could implement more aggressive regeneration protocols, such as thermal treatment in an inert atmosphere or washing with a 0.1 M NaOH solution, to fully restore the adsorbent’s capacity and extend its operational lifespan.

Beyond its primary function as an adsorbent, the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite also showcased ancillary properties beneficial for advanced wastewater treatment. UV-Vis DRS analysis confirmed an extended visible-light absorption profile, suggesting its potential as a potent photocatalyst for the degradation of residual organic pollutants, thereby offering a pathway for integrated adsorption-photocatalysis systems.

In summary, this work establishes the ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite as a superior, robust, and multifunctional material. Its quantified high capacity (60 mg g−1), fast kinetics (~ 180 min), and excellent recyclability (88% retention over 5 cycles) position it as a highly promising and sustainable solution for the targeted removal of proteinaceous contaminants in advanced wastewater treatment processes. The insights gained into the synthesis-structure-performance relationship provide a valuable blueprint for the future development of MOF-based hybrid materials for environmental remediation.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kaveh, R., Alijani, H. & Beyki, M. H. Oxine–mediated magnetic MnFe2O4-starch-based surface imprinted polymer toward highly selective Pb (II) targeting from aqueous environment. Microchem. J. 198, 110192 (2024).

Iqbal, A., Jalees, M. I., Farooq, M. U. & Cevik, E. Mu’azu, synthesis and application of maghemite nanoparticles for water treatment: Response surface method. Desalin. Water Treat. 244, 212–225 (2021).

Zou, M., Dong, M. & Zhao, T. Advances in metal-organic frameworks MIL-101 (Cr). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9396 (2022).

Mofidian, R. et al. Adsorption of lactoferrin and bovine serum albumin nanoparticles on pellicular two-layer agarose-nickel at reactive blue 4 in affinity chromatography. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105084 (2021).

Iqbal, A., Jalees, M. I., Farooq, M. U., Cevik, E. & Bozkurt, A. Effectual adsorptive performance of metal-based engineered nanoparticles for surface water remediation: Systematic optimization by box-behnken design. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 6819–6834 (2025).

Liu, Y., Gao, C., Liu, L., Li, Y. & Guo, X. A photovoltaic powered ocean-based electrochemical system produces highly oxidizing active substances for simultaneous removal of antibiotics and heavy metals from mariculture wastewater. Water Res. 286, 124177 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Synthesis methods, performance optimization, and application progress of metal–organic framework material MIL-101 (Cr). Chemistry. 7, 78 (2025).

Iqbal, A., Cevik, E., Alagha, O. & Bozkurt, A. Highly robust multilayer nanosheets with ultra-efficient batch adsorption and gravity-driven filtration capability for dye removal. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 109, 287–295 (2022).

Abbasi, F., Gas-Phase, B. & Oxidation, C. O. Unveiling synergistic Pd–PA interactions confined within MIL-101 (Cr) (2025).

Macedo, O. B. & Oliveira, A. L. M. I.M.G.d. Santos, zinc tungstate: A review on its application as heterogeneous photocatalyst. Ceramica 68, 294–315 (2022).

Iqbal, A., Jalees, M. I., Farooq, M. U., Cevik, E. & Bozkurt, A. Superfast adsorption and high-performance tailored membrane filtration by engineered Fe–Ni–Co nanocomposite for simultaneous removal of surface water pollutants. Colloids Surf. A. 652, 129751 (2022).

Munawar, T. et al. Enhanced charge carriers separation/transportation via S-scheme ZnCeS–ZnWO heterostructure nanocomposite for photodegradation of synthetic dyes under sunlight. Mater. Chem. Phys. 314, 128938 (2024).

Iqbal, A. et al. Ultrahigh adsorption by regenerable iron-cobalt core-shell nanospheres and their synergetic effect on nanohybrid membranes for removal of malachite green dye. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107968 (2022).

al-Salmi, F. A., Fayad, E., Mubarak, M. F. & Hemdan, M. Dual removal of thallium (Tl+) and auramine O using alginate-coated iron oxide nanocomposites for sustainable wastewater treatment. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 1–28 (2025).

Mofidian, R., Barati, A., Jahanshahi, M. & Shahavi, M. H. Optimization on thermal treatment synthesis of lactoferrin nanoparticles via Taguchi design method. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–9 (2019).

Mofidian, R., Barati, A., Jahanshahi, M. & Shahavi, M. H. Fabrication of novel agarose–nickel bilayer composite for purification of protein nanoparticles in expanded bed adsorption column. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 159, 291–299 (2020).

Adaileh, A. et al. Development of Cu–ZnO ZrO2 based polyacrylonitrile polymer composites for removing pharmaceutical pollutants and heavy metals from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 15, 22250 (2025).

Mofidian, R., Hassankhani, I., Jahanshahi, M., Hosseini, S. S. & Miansari, M. Cost Effective Design of a 200 kW On-grid Rooftop Photovoltaic (System Using PVsyst Software in Shiraz, 2024).

Mofidian, R. CFD modeling of DME synthesis based on methanol dehydration process by an adiabatic reactor: Characterization. Latin Am. Appl. Res. Int. J. 54, 595–600 (2024).

Mubarak, M. F. et al. Enhanced performance of Chitosan via a novel quaternary magnetic nanocomposite Chitosan/grafted halloysitenanotubes@ ZnγFe3O4 for uptake of cr (III), Fe (III), and Mn (II) from wastewater. Polymers 13, 2714 (2021).

Jahanshahi, M., Mofidian, R. & Hakimizadeh, M. Membrane distillation configurations and hybrids: A review. J. Eng. Appl. Res. 1, 13–27 (2024).

Mofidian, R., Hosseini, S. S., Miansari, M. & Salmani, H. Separation and clarification of Mazandaran wood and paper factory effluent to remove heavy metals using Zeolite–Agar nanoadsorbent immobilized by cibacron blue dye ligand. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 41, 1–12. (2024).

Abdi, B., Tayebee, R., Rezaei-Seresht, E., Zonoz, F. M. & Mofidian, R. ZnO/AgSbO3 as an improved nanophotocatalyst in the synthesis of some naphthopyranopyrimidines. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 170, 113212 (2024).

Mofidian, R. Modeling and preparation of nano adsorbents laminated with agarose for expanded bed adsorption in protein purification. Discover Mater. 5, 1–24 (2025).

Jahanshahi, M., Mofidian, R. & Hakimizadeh, M. Innovative membrane distillation configurations for enhanced performance: A review. J. Eng. Appl. Res. 1, 13–27 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding has been given to support this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Roozbeh Mofidian: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis and writing. Behnaz Abdi: Methodology. Hosna Malmir: Investigation and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have given their final approval for the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mofidian, R., Abdi, B. & Malmir, H. ZnWO3/MIL-101(Cr) nanocomposite for enhanced Lactoferrin adsorption from wastewater. Sci Rep 15, 42188 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26054-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26054-5