Abstract

Forested areas, as important ecological resources, need to be patrolled regularly and efficiently to prevent fires, monitor pests and protect the ecology. Traditional methods relying on manual patrols or manned aircrafts face challenges such as low efficiency, high cost, and high safety risks, especially in complex terrains. In this paper, a coverage path planning algorithm based on spatial position ordering and convex decomposition is proposed for the coverage path planning problem of multiple unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in concave polygonal regions. The algorithm decomposes the complex forested area into consecutive convex polygonal subregions by selectively removing concave vertices and improving the pre-ordered ear-shearing method. To further achieve balanced and spatially contiguous coverage, a region allocation method based on spatial position ordering and an explicit adjacency constraint (via a shared-edge-checking candidate set) is proposed to ensure region balance and neighbourhood constraints. Experimental results in a simulated forest area with 14 concave vertices show that the proposed method can reduce the coverage time by 54.7% and the total path length by 26.3% compared with single UAV operation. Further validation in conjunction with real terrain data from Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province, reveals that through dynamic flight altitude optimisation (H = 150 m), the coverage rate is increased to 97.8% and the shading coefficient is reduced to 0.09, which verifies that the multi-UAV cooperative strategy still maintains its high efficiency in real scenarios. Additional comparisons performed under multi-UAV configurations also validated the efficiency of the algorithm, outperforming existing methods in minimising coverage time and total path length while maintaining a balanced task allocation. The algorithm greatly improves the coverage efficiency of forest area detection and provides technical support for dynamic monitoring of forest resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an important part of the global ecosystem, the health of forests directly affects biodiversity conservation and carbon sink functions1. Traditional forest inspections rely on manual patrols or manned aircraft, which are inefficient, costly and risky, especially in complex terrain (e.g., mountainous areas and river valleys) where it is difficult to achieve comprehensive coverage2,3. In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology has gradually become a core tool for forest dynamic monitoring by virtue of its advantages such as high flexibility and low operating cost4,5. By carrying multispectral sensors and infrared cameras, UAVs can efficiently acquire key information such as surface temperature and vegetation index, providing data support for fire early warning and pest identification6,7. However, the actual forest areas are often characterised by irregular concave polygons (e.g., mountain depressions, river cuts) and significant terrain undulations, which lead to two major challenges in multi-UAV cooperative coverage path planning8: first, the spatial dispersion of sub-areas generated by the concave polygon decomposition increases the redundancy of the paths; and second, the terrain obstruction and altitude variations affect the detection accuracy and the mission balance9,10.

For the concave polygon region decomposition problem, existing studies mainly use static convex decomposition strategies. For example, Cabreira et al11. proposed a grid-based coverage path planning method, but their fixed decomposition strategy has high path redundancy in complex concave polygons; and the hierarchical coverage strategy developed by Vasquez-Gomez et al12., although applicable to convex regions, is unable to deal with the field-of-view blindness within concave polygons. Recently, Zheng et al13. tried to combine deep learning to dynamically adjust the decomposition threshold, but the high computational complexity makes it difficult to meet the real-time inspection demand. In terms of multi-UAV task allocation, the auction algorithm proposed by Cheng et al14. can balance the load but ignores the spatial continuity of sub-regions, resulting in redundant UAV flight paths across regions. In addition, existing studies mostly assume ideal planar environments and lack quantitative analysis of slope occlusion and flight altitude optimisation in real terrain. For example, Torresan et al15. found in a European forest monitoring experiment that unoptimised flight height leads to more than 25% detection blindness, which is not included in the constraints of existing path planning models.

Aiming at the above problems, this paper proposes a multi-UAV cooperative coverage path planning algorithm for concave polygonal forest areas. The main contributions are as follows:

-

1.

Proposes a selective concave point removal strategy and a pre-ordered improved ear-cutting method, which reduces the decomposition complexity of concave polygons through dynamic threshold control and vertex pre-ordering;

-

2.

Designs an area allocation method based on spatial position ordering, combining area accumulation and adjacency constraints to achieve balanced allocation of multi-UAV tasks;

-

3.

Height-optimized model for terrain perception: Incorporating the slope occlusion factor to quantify the influence of terrain undulations, and dynamically adjusting the flight altitude to balance detection accuracy and coverage efficiency.

Problem description

In order to formally describe the multi-drone coverage path planning problem, this paper establishes a mathematical model based on the following parameters and constraints:

Given a concave polygonal region P (a sequence of vertices \(V = \left\{ {v_{1} ,v_{2} , \ldots ,v_{m} } \right\},\) where \(v_{i} = \left( {x_{i} ,y_{i} } \right)\)), the set of drones \(U = \left\{ {U_{1} ,U_{2} , \ldots ,U_{n} } \right\},\) and the detection model of each UAV is a rectangular region (width is \(W = 2L\tan \alpha,\) height is \(H = 2L\tan \beta,\) flight height is L, minimum turning radius is \(\mathcal{R}\)), and the set of covered paths needs to be planned \(P = \left\{ {Path_{1} ,Path_{2} , \ldots ,Path_{n} } \right\},\) satisfying the following constraints:

-

1.

UAVs are considered as mass points: Ignoring their volume and shape to simplify flight path calculations.

-

2.

Flight altitude remains constant: UAVs maintain a fixed flight altitude during flight to simplify the modeling of the detection area.

-

3.

Terrain is relatively gentle: The undulations of the area to be covered are small and can be ignored in terms of their impact on UAV flight.

-

4.

Full coverage: any point within the region P is covered by at least one UAV \(\left( {\mathop \sum \limits_{i} X_{i,j} \ge 1} \right);\)

-

5.

Path feasibility: the paths are continuous and satisfy the minimum turning radius constraint, and the starting point is located at the boundary of the region;

-

6.

Mission balancing: the variance of the coverage area of each UAV does not exceed the threshold ε1617,.

The detection model of UAVs has been simplified, and its geometric representation is shown in Fig. 17.

The optimization objective is to minimize the total weighted sum of coverage time and path length:

where ti is the flight time of the UAV; \(\lambda \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) is the weighting factor, balancing time and energy priorities18; ε is the allowable coverage area equalisation error; \({\mathcal{R}}\) is the minimum turning radius, equal to the detection radius (assumed condition). ΓP is total area of the target area.And the constraints is following: (1) is to enforce that the total area covered by the UAV fleet is greater than or equal to the size of the target area to ensure mission integrity; (2) is to avoid overloading some drones with tasks and leaving others idle, to improve system reliability and to ensure that coverage tasks are completed simultaneously.The integral term \(\int {\left\| {\frac{dPath}{{dt}}} \right\|} dt\) is computed numerically by discretizing paths into 1-m segments.

Decomposition of concave polygonal areas

Preprocessing of concave polygons

Since UAVs consume much more energy during turning than during straight-line flight, literature4 proposes a method for covering convex polygonal areas with the shortest flight path, i.e., UAVs fly along the direction perpendicular to the width, resulting in the fewest turns and the shortest flight path. This transforms the coverage path planning problem for convex polygonal areas into a problem of finding the width of the convex polygon. However, actual areas to be covered are mostly irregular concave polygons, which need to be processed into convex polygonal areas before traversal. When dealing with concave points, the first step is to identify them. Generally, the cross product of vectors is used to determine whether a vertex is a concave point. Let there be two vectors \(V_{1} \left( {x_{1} ,y_{1} } \right)\) and \(V_{2} \left( {x_{2} ,y_{2} } \right),\) then the cross product of the two vectors can be expressed as:

Based on the properties of the cross product:

If \(V_{1} \times V_{2}> 0,\) then \(V_{2}\) is in the counterclockwise direction relative to \(V_{1}\).

If \(V_{1} \times V_{2} = 0,\) then \(V_{2}\) and \(V_{1}\) are collinear.

If \({\text{V}}_{1}\times {\text{V}}_{2}<0,\) then \({\text{V}}_{2}\) is in the clockwise direction relative to \(V_{1}\).

For three adjacent vertices of a polygonal area forming two vectors \(V_{i - 1} V_{i}\) and \(V_{i} V_{i + 1},\) the cross product is:

Based on the properties of the cross product, when \(\text{F}>0,\) the vertex \({\text{V}}_{\text{i}}\) is a convex point; when \(\text{F}<0,\) the vertex \({\text{V}}_{\text{i}}\) is a concave point19.

To reduce the complexity of concave polygonal areas, a selective removal strategy for concave points is introduced. For convenience, two thresholds are set:

(1) Area ratio threshold: The ratio of the area of the redundant triangle formed by connecting the two adjacent vertices of a concave point to the entire area. When this ratio is less than the set threshold, the concave point is removed by connecting the two adjacent vertices of the concave point.

where r is the ratio of the area of the redundant triangle to the entire area, usually set to a small value (such as 0.1 or 0.05) to avoid excessive removal of concave points leading to area distortion,\({\text{K}}_{\text{i}}\) is the area of the redundant triangle,\({\text{K}}_{\text{total}}\) is the area of the entire region.

(2) External angle threshold of concave points: When the external angle of a concave point is less than the set threshold, the concave point is removed by connecting the two adjacent vertices of the concave point.The threshold is usually set to a small angle (e.g. 10° or 20°) to determine if the concave point needs to be removed.

By selectively removing concave points, the complexity of concave polygonal areas can be reduced, avoiding the generation of excessive invalid coverage areas. Figure 2 shows an example of removing concave points based on the area ratio threshold, and Fig. 3 shows an example of removing concave points based on the external angle threshold of concave points.

Concave polygon decomposition based on pre-sorted improved ear clipping method

The traditional ear clipping method (Ear Clipping Method) is a simple and widely used polygon triangulation algorithm. Its basic idea is to identify and remove “ears” in the polygon, i.e., vertices that, together with their two adjacent vertices, form a triangle that does not contain any other vertices of the polygon. The algorithm starts from any vertex, finds an ear, and cuts it off to form the first triangle, then continues to find the next ear in the remaining polygon, repeating this process until the polygon is completely decomposed into triangles20. The steps of the traditional ear clipping method are shown in Fig. 4.

To improve the efficiency and reliability of the algorithm, a pre-sorted improved ear clipping method is introduced. This algorithm adds a vertex pre-sorting step to the traditional ear clipping method, with the specific process as follows:

(1) Vertex Sorting: Sort all vertices V of the polygon by their coordinates in ascending order. If the x-coordinates are the same, sort by the y-coordinates to ensure the uniqueness and consistency of the sorting.

where \(V_{sorted}\) is the sorted list of polygon vertices, V is the original list of polygon vertices.

(2) Marking Concave and Convex Points: Traverse the vertices of the polygon in the pre-sorted order. For each vertex, determine whether it is a concave or convex point by calculating the cross product of vectors. If the cross product is greater than 0, the vertex is a convex point; if the cross product is less than 0, the vertex is a concave point. For a vertex \({\text{V}}_{\text{i}},\) the cross product calculation formula is:

(3) Finding Ears

Start checking from convex points: Since concave points cannot directly form ears, start checking from the marked convex points. For each convex point, let its previous vertex be M and the next vertex be N, forming a triangle ΔPMN.

Check if there are other vertices inside the triangle: Traverse the other vertices of the polygon and determine whether there are other vertices inside the triangle by calculating the cross product of vectors from the triangle’s edges. For example, for edge PM and other vertices Q, of the polygoncalculate the cross product of vectors \(\overrightarrow{\text{PM}}\) and \(\overrightarrow{\text{PQ}}\). If the point Q is on the same side of the edge as the vertex N (same cross product sign), it satisfies the condition for that edge; only when point Q satisfies the inside conditions for all three edges is it considered inside the triangle ΔPMN.

Check if the edge is inside the polygon: Determine whether the line segment MN is inside the polygon by checking whether it intersects with other edges of the polygon at points other than the polygon’s vertices. If no intersections occur, the line segment is inside the polygon.

If the ΔPMN contains no other vertices of the polygon and the line segment is inside the polygon, it is an ear of the polygon.

(4) Cutting Ears

Save the ear triangle ΔPMN: If an ear is identified, save it to the triangulation result.

Update the polygon: Remove the vertex P from the polygon and update the connectivity of the adjacent vertices to form a new polygon.

(5) Repeat the Process: Repeat steps 3 and 4 on the updated polygon until only three vertices remain, at which point the remaining part is also a triangle, completing the triangulation.

The flowchart of the concave polygon decomposition based on the pre-sorted improved ear clipping method is shown in Fig. 5.

Multi-UAV coverage path planning algorithm

Multi-UAV region allocation method based on spatial position sorting

After the concave polygonal area is convexly decomposed, the area to be covered is divided into several triangular sub-regions. The next task is to allocate these sub-regions to multiple UAVs for coverage. Depending on the allocation of UAVs, a single UAV may correspond to one sub-region or multiple sub-regions. To efficiently complete the coverage task, a region allocation method based on spatial position sorting is proposed in this paper to allocate the decomposed sub-regions to multiple UAVs, ensuring that the regions covered by each UAV are spatially continuous and the areas are relatively balanced.

For the case where a single UAV corresponds to one sub-region, the flight direction of the UAV is determined by calculating the width of the sub-region, and a scan line coverage strategy is adopted to ensure the shortest path and the fewest turns. For the case where a single UAV corresponds to multiple sub-regions, the order of sub-region traversal and the planning of redundant paths are optimized to reduce the length of redundant paths, ensuring the smoothness and efficiency of the coverage path.

Problem description

In the multi-UAV area coverage problem, given n triangular sub-regions with unequal areas and m UAVs, the goal is to allocate these sub-regions to UAVs such that the area covered by each UAV is as equal as possible, and the covered triangular sub-regions are spatially adjacent. To achieve this goal, a multi-UAV region coverage allocation method based on spatial position sorting is proposed in this paper. The method sorts the triangular sub-areas by their spatial positions, such as sorting them sequentially from left to right according to the position of the centre point of the triangle, and sorting them in top-to-bottom order when the centre points are at the same position vertically, and adopts an area accumulation strategy to allocate adjacent areas to UAVs, aiming to achieve equal area coverage for each UAV while ensuring that the number of triangular sub-areas covered is an integer number. This method achieves a balanced distribution of area as much as possible while ensuring the adjacency of the covered regions.

Method steps

(1) Calculate the total area:

Let the areas of the n triangles be \(A_{1} ,A_{2} , \ldots ,A_{n},\) then the total area is:

(2) Determine the target coverage area for each UAV:

where \({\text{S}}_{\text{drone}}\) is the target coverage area for each UAV, m is the total number of UAVs.

(3) Sort the triangles by spatial position and initialize:

Sort the n triangles based on the coordinates of their centroids (e.g., first by x-coordinate, then by y-coordinate) to obtain a sequenced list \(T_{1} ,T_{2} , \ldots ,T_{n} .\) This sorting promotes the proximity of spatially adjacent regions in the list. Initialize a global list of unassigned regions \(\left| {U = \left\{ {T_{1} ,T_{2} , \ldots ,T_{n} } \right\}} \right|.\)

(4) Area Accumulation Allocation via a Shared-Edge Candidate Set:

Foreach UAV k \(\left(\text{k}=\text{1,2},\dots ,\text{m}\right):\) (a) Seed Selection: If u is not empty, select the first triangle in u as the seed. Remove it from u and assign it to UAV k.This forms the initial cluster \({\text{c}}_{\text{z}}\) for UAV k and sets the current accumulated area \({\text{S}}_{\text{z}}=\) area(seed). (b) Candidate Set Initialization: Initialize the candidate set Candidate for UAV k.This set contains all unassigned triangles (i.e., in \(\upupsilon )\) that share at least one common edge with any triangle currently in cluster \({\text{c}}_{\text{k}}.\) (c) lterative Assignment: While( s \({ }_{\text{z}}<\) s_drone) and (Candidate, is not empty): From Candidate。select the triangle Tj whose area, when added, minimizes the absolute difference \(|({\text{S}}_{\text{k}}+\) area(T_j))- S_drone|. -Assign Tj toUAV k.Remove Tj from both u and Candidate.Add area(Tj) to Se. -Update Candidate.:Add to candidate. all triangles in u that share a common edge with Tj.This step is crucial for ensuring contiguity. (d) Finalization: Proceed to allocate the next UAV(k + 1).

(5) Assign Remaining Regions:

After processing all m UAVs, if any regions remain in u(due to approximation), assign them to the last UAV to ensure complete coverage.

Multi-UAV Region Allocation Method Based on Spatial Position Sorting is detailed in Algorithm 1.

The multi-UAV region allocation method based on spatial position sorting ensures that the regions covered by each UAV are spatially continuous by sorting and allocating adjacent triangles, avoiding dispersed coverage areas and significantly improving coverage efficiency. Additionally, the method achieves balanced area allocation by using an area accumulation strategy, ensuring that the coverage area of each UAV is as close to the target area as possible, ensuring fairness and balance in task allocation. Moreover, the method has low computational complexity, is easy to implement, and is suitable for scenarios with high real-time requirements, especially showing excellent performance in small-scale problems. For large-scale problems, dynamic programming or heuristic algorithms can be combined to further optimize and enhance the robustness and applicability of the algorithm. Through this method, not only are the adjacency and balanced area allocation problems in UAV area coverage solved, but also an efficient and flexible solution is provided for multi-UAV collaborative coverage tasks, laying a solid foundation for subsequent research.

Sub-region coverage search method

After the concave polygonal area is convexly decomposed and the sub-regions are allocated, the next task is to plan the coverage path for each sub-region. Depending on the allocation of UAVs, a single UAV may correspond to one sub-region or multiple sub-regions. For these two cases, different coverage path planning methods are adopted to ensure the shortest and most efficient coverage path.

Coverage path planning for a single UAV corresponding to one sub-region

For the case where a single UAV corresponds to one sub-region, the coverage path planning method proposed by Chen Hai21 is used. This method theoretically proves that the turning process is less efficient than straight-line flight, transforming the coverage path planning problem for convex polygonal areas into a problem of finding the width of the convex polygon. By calculating the width of the sub-region, the flight direction of the UAV is determined, and a scan line coverage strategy is adopted. The UAV flies along the direction of the supporting parallel lines where the width appears, achieving the fewest turns and thus the shortest flight path. The specific steps are as follows:

-

(1)

Calculate the width of the sub-region: For each sub-region, calculate its minimum width W, i.e., the minimum span of the sub-region. The direction of the supporting parallel lines corresponding to the width is the flight direction of the UAV.

-

(2)

Scan line coverage: The UAV flies along the direction of the supporting parallel lines, using a scan line coverage strategy with a spacing of the UAV’s detection width L to ensure continuous paths and complete coverage without omission.

Coverage Path Planning for a Single UAV Corresponding to Multiple Sub-regions

For the case where a single UAV corresponds to multiple sub-regions, the method proposed by Wang Hongxing22 is improved for coverage path planning. The core idea of this method is to optimize the traversal order of sub-regions and plan redundant paths to reduce the length of redundant paths, ensuring the smoothness and efficiency of the coverage path. The specific steps are as follows:

-

(1)

Optimization of sub-region traversal order: For multiple sub-regions, calculate the entry and exit points of each sub-region.

-

(2)

Planning of redundant paths: After completing the coverage of the current sub-region, the UAV enters the next sub-region through the shortest path. Redundant paths are planned using straight lines or Dubins curves to ensure smoothness and meet the minimum turning radius constraint.

-

(3)

Coverage path planning: Within each sub-region, the flight direction of the UAV is determined by calculating the width of the sub-region, and a scan line coverage strategy is adopted. The UAV flies along the direction of the supporting parallel lines where the width appears, achieving the fewest turns and thus the shortest flight path.

Results

Experimental setup

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed multi-UAV coverage path planning algorithm, simulation experiments were conducted. Runs on a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-12700H processor, 16 GiB RAM. The simulation platforms are MATLAB R2023a + Python 3.9. The experimental scenario was forest inspection, with a given concave polygonal forest area P with 14 vertices, and the vertex coordinates were:

The detection radius and minimum turning radius of the UAV were 200m, and the turning process of the UAV was selected as the normal turning process. A scan line coverage strategy was used to ensure path continuity. The area to be covered P is shown in Fig. 6.

Concave decomposition

The area coverage ratio threshold was set to 0.1, meaning that if the redundant area ratio after removing a concave point was ≤ 0.1, the concave point was deleted. The angle threshold was set to 15°, i.e., when the area angle was less than 15°, resulting in overly narrow areas, the concave point was deleted. The polygon after removing concave points that met the conditions is shown in Fig. 7.

If the polygon had no residual concave points after preprocessing, it was directly traversed; otherwise, convex decomposition was performed. For the remaining concave polygon after removing concave points that meet the conditions, the pre-sorted improved ear clipping method proposed in Section "Concave polygon decomposition based on pre-sorted improved ear clipping method" was used to decompose the concave polygon into multiple triangular sub-regions. Specifically, a Cartesian coordinate system was first established, and all vertices of the polygon were sorted in ascending order of their x-coordinates (and y-coordinates if x-coordinates were the same)—consistent with the vertex sorting step in the pre-sorted improved ear clipping method. Then, vertices were traversed in the pre-sorted order to identify and clip ears (convex triangles with no internal vertices and edges inside the polygon) until only three vertices remained; the remaining part was also a triangle, completing the triangulation. First, a Cartesian coordinate system was established, and all vertices of the polygon were sorted by their coordinates in ascending order. The sorted polygon is shown in Fig. 8. Then, the vertices were traversed in the pre-sorted order to find and cut ears until only three vertices remained, at which point the remaining part was also a triangle. The polygon after completing the triangulation is shown in Fig. 9.

Multi-UAV allocation

The concave polygonal area was decomposed into 9 triangular regions. Then, these 9 triangular regions were sorted by spatial position in the order of left to right and then top to bottom (sorted by the x-coordinate of the triangle centroid first, then the y-coordinate)—consistent with the spatial position sorting strategy in Section "Method Steps". The total area was calculated to determine the target coverage area for each UAV. During the allocation process, the area accumulation method was combined with the shared edge check (a key constraint of spatial continuity): starting from the first sorted triangle, only triangles adjacent to the currently allocated region (verified by checking for shared edges between triangles) were added to the candidate set of the current UAV. The accumulation stopped when the accumulated area approached the target coverage area, ensuring that the regions covered by each UAV remained spatially continuous. Using this method, the 9 triangular regions were allocated to 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 UAVs, respectively. Examples of the distribution results are shown in Figs. 10 and 11—in these figures, the regions covered by each UAV (e.g., P1, P2, P3 for 3 UAVs) are connected via shared edges, confirming the spatial continuity of the allocation.

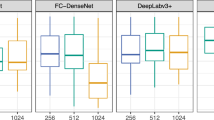

Table 1 compares the coverage time, total coverage distance, number of turns, and area variance of the regions covered by each UAV for 5 different numbers of UAVs in area P. Increasing the number of UAVs can reduce coverage time and total coverage distance, but the marginal benefit decreases. With 5 UAVs, the coverage time was reduced to 67 min, a 54.7% reduction compared to 1 UAV, and better than 7 UAVs (61 min) and 9 UAVs (49 min) in terms of cost-effectiveness. The single UAV had the longest path (345.65 km) because it had to traverse all sub-regions. With 5 UAVs, due to the balanced task allocation, the transfer paths between sub-regions were reduced, also better than 7 and 9 UAVs in terms of cost-effectiveness. In terms of the number of turns, 5 UAVs had the fewest turns because the number of covered sub-regions was moderate, and the path continuity was higher. In terms of load balancing, 9 UAVs had the largest area variance because the area differences of individual sub-regions were not shared, while 5 UAVs had the smallest area variance, indicating that the allocation strategy effectively balanced the workload. This experiment shows that taking half the number of triangular regions decomposed in the target area (rounded up) as the number of UAVs can optimally balance coverage time and path length, while the number of turns is controllable, and the load balancing is high. The coverage path of 5 UAVs for area P is shown in Fig. 12.

Real terrain validation

By introducing real terrain data (DEM) and slope shading model, the effect of different flight heights on coverage efficiency is verified, and the comprehensive performance is analysed in conjunction with the multi-UAV cooperative strategy. The experiment used real terrain data (DEM resolution: 10m) from Xishuangbanna rainforest in Yunnan Province, and selected a typical concave polygon area (vertex coordinates: E101°15′–101°30′, N21°10′–21°25′) with a maximum slope angle of 25° and an average elevation difference of 150 m. To evaluate the effect of flight height on the coverage performance, the UAV flight height gradient is set as H = {100m, 150m, 200m} and the slope shading coefficient \(\upeta\) is defined:

where \({\uptheta }_{\text{i}}\) is the pitch angle of the UAV to the ground plane at the \(\text{i}\)-th detection point and N is the total number of detection points.

Table 2 shows the experimental results of fixing the number of 5 UAVs and testing the coverage performance at different heights respectively. When H = 150 m, the lowest occlusion coefficient (\(\upeta\)=0.09), the highest coverage (97.8%), and the shorter path length (265.2 km) indicate the best UAV field of view and terrain suitability at this altitude.

Comparative analysis

Table 3 compares the total distance covered and the total time taken by the UAV to cover area P at an altitude of 150m for the three different coverage methods. The convex polygon coverage algorithm converts the concave polygon into the smallest convex polygon by removing the concave points, dividing it equally into five sub-regions and then covering it using a single scan line. The improved region decomposition coverage algorithm divides the region into multiple convex polygons by convex decomposition and then randomly assigns them to 5 UAVs for coverage. The results are shown in Table 3, the convex polygon coverage algorithm produces too many redundant paths, the improved region decomposition coverage algorithm randomly assigns leads to too much time, and this paper’s method significantly outperforms the comparison algorithms in all indicators.

Conclusion

In this study, a cooperative coverage algorithm based on concave point removal and spatial position ordering is proposed for the multi-UAV coverage path planning problem in concave polygonal forest areas. The complex region is transformed into a continuous convex subregion by dynamic threshold control with concave point removal and improved ear-cut decomposition. A region allocation strategy combining region accumulation and a rigorous shared-edge-checking candidate set mechanism achieves task load balancing, guarantees spatially contiguous assignments, and minimizes path redundancy. Simulation experiments confirm that the algorithm can effectively reduce the coverage time and total path length compared with single UAV operation. It also achieves a balance between efficiency and accuracy through real terrain simulation, introducing slope shading coefficients and dynamically adjusting the height. Further comparative analyses highlight the robustness of the algorithm in multi-UAV scenarios, which consistently outperforms alternative methods such as convex polygonal coverage and improved region decomposition methods. This improvement stems from the balanced spatial allocation of sub-regions and the optimised traversal order, which minimise redundant paths and improve coordination efficiency.

The present algorithm provides effective technical support for dynamic monitoring of forest resources, which is especially suitable for terrain fragmentation areas. However, the current model does not consider the effects of real-time wind speed perturbation and sensor resolution decay with height. In the future, meteorological data and multi-objective optimisation (e.g. NSGA-II) can be fused to dynamically adjust the flight altitude and path to cope with complex terrain and meteorological disturbances23. In addition, the static shading model used in real experiments can be further extended to dynamic vegetation shading analysis to improve fire monitoring accuracy.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study, including the coordinates of the concave polygonal region, UAV parameters, and simulation results, are fully described within the manuscript. The vertex coordinates of the tested forest area and UAV specifications (e.g., detection radius, minimum turning radius) are explicitly provided in Section "Conclusion" (“Results”) of this paper. The MATLAB/Python code used for decomposing the concave polygon and planning UAV paths is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Prăvălie, R. Major perturbations in the Earth’s forest ecosystems. Possible implications for global warming. Earth-Sci. Rev. 185, 544–571 (2018).

Debnath, D. et al. A Review of UAV Path-Planning Algorithms and Obstacle Avoidance Methods for Remote Sensing Applications. Remote Sensing 16(21), 4019 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Estimation of aboveground biomass of different vegetation types in mangrove forests based on UAV remote sensing. Sustain. Horizons 11, 100100 (2024).

Mohsan, S. A. H. et al. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs): Practical aspects, applications, open challenges, security issues, and future trends. Intel. Serv. Robot. 16(1), 109–137 (2023).

Dainelli, R. et al. Recent advances in unmanned aerial vehicle forest remote sensing—A systematic review. Part I: A general framework. Forests 12(3), 327 (2021).

Xu, Y., Li, J. & Zhang, F. A UAV-based forest fire patrol path planning strategy. Forests 13(11), 1952 (2022).

Guo, Q. M. et al. Improved ACO based coverage path planning of unmanned reconnaissance aircraft in concave area. Electron. Opt. Control. 31(08), 23–31 (2024).

Torres, M. et al. Coverage path planning with unmanned aerial vehicles for 3D terrain reconstruction. Expert Syst. Appl. 55, 441–451 (2016).

Ecke, S. et al. UAV-based forest health monitoring: A systematic review. Remote Sensing 14(13), 3205 (2022).

Seifert, E. et al. Influence of drone altitude, image overlap, and optical sensor resolution on multi-view reconstruction of forest images. Remote Sensing 11(10), 1252 (2019).

Cabreira T M, Ferreira P R, Di Franco C, et al. Grid-based coverage path planning with minimum energy over irregular-shaped areas with UAVs. In: 2019 international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS). IEEE, 2019: 758–767.

Vasquez-Gomez, I. J. et al. Coverage path planning for 2D convex regions. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. Special Sect. Unmanned Syst. 97(99), 81–94 (2020).

Zheng, T., Jin, Y., Zhao, H., et al. Deep reinforcement learning based coverage path planning in unknown environments[C]//2024 6th International Conference on Frontier Technologies of Information and Computer (ICFTIC). IEEE, 2024: 1608–1611.

Cheng, Q., Yin, D., Yang, J., et al. An auction-based multiple constraints task allocation algorithm for multi-UAV system. In: 2016 International Conference on Cybernetics, Robotics and Control (CRC). IEEE, 2016: 1–5.

Torresan, C. et al. Forestry applications of UAVs in Europe: A review. Int. J. Remote Sens. 38(8–10), 2427–2447 (2017).

Sathyaraj, B. M. et al. Multiple UAVs path planning algorithms: a comparative study. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Making 7, 257–267 (2008).

Li, Y. et al. A Global Coverage Path Planning Method for Multi-UAV Maritime Surveillance in Complex Obstacle Environments. Drones 8(12), 764 (2024).

Cabreira, T. M. et al. Energy-aware spiral coverage path planning for uav photogrammetric applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3(4), 3662–3668 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Coverage path planning for UAVs based on enhanced exact cellular decomposition method. Mechatronics 21(5), 876–885 (2010).

Wang, Z. L., Luo, D. L. & Wu, S. X. A UAV path planning method for concave polygonal area coverage. Chinese J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 26(01), 95–100 (2019).

Chen, H. et al. An Algorithm of Coverage Flight Path for UAVs in Convex Polygon Areas. Acta Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica 31(09), 1802–1808 (2010).

Wang, H. X., Ma, X. J. & Zhang, C. S. An algorithm of coverage path planning for UAV in concave polygon area. Chinese J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 28(06), 46–52 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Research on multi-UAV cooperative dynamic path planning algorithm based on conflict search. Drones 8(6), 274 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Discipline Construction Project of Anhui Science and Technology University (Grant No. XK-XJGY002) and the Natural Science Research Key Project of Anhui Provincial Education Department (Grant No. 2022AH051642).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. and C.W. conceived the experiment(s). B.K. conducted the experiment(s). B.K. and J.Z. performed statistical analysis and figure generation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests, financial or non-financial, that could influence the objectivity or interpretation of the research presented in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, B., Wang, C., Su, Y. et al. Multi-UAV forest area inspection path planning based on concave polygon region decomposition. Sci Rep 15, 41990 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26060-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26060-7