Abstract

With the continuous expansion of orchard planting area and fruit production in China, the problem of low precision in the application of powdered organic fertilizers has become increasingly prominent. To address this issue, a specialized grooved-wheel fertilizer discharge device for pit fertilization machines was designed and optimized in this study. A RecurDyn–EDEM coupled simulation model was established, in which the fertilizer application rate—defined as the ratio of fertilizer mass deposited at the pit bottom to the total discharged mass—was selected as the evaluation index. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed to develop a regression model and optimize both operational and structural parameters. Specifically, the dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle were chosen as key factors for optimization. The results indicated that the optimal parameters were a dial plate speed of 64.3 r/min and a scraper inclination angle of − 17.3°, under which the single application amount reached 637.98 g and the fertilizer application rate was 97.57%. The deviation between the bench test and the simulation under the optimal parameters was only 2.11%. This research, by integrating theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and bench testing, provides a valuable reference for the innovative design of powdered organic fertilizer applicators in orchards of the hilly regions of Southwest China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

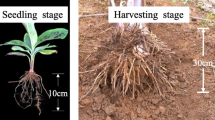

In 2022, the orchard planting area and fruit production in China reached 13.0095 million hm² and 312.9624 million tons, respectively1. At the same time, the proportion of fruit planting area in Southwest China has shown a continuous upward trend, increasing from 8.78% to 10.76% in 1985 to 20.03% and 31.39% in 2019, respectively2. Moreover, the growth rate of fruit yield has exceeded that of planting area, which can be attributed to improvements in fruit varieties, orchard management practices, and the application of mechanization3. Among these, trench fertilization is both a key orchard management practice and a form of mechanized operation. It plays an important role in orchard production, as its technical level directly affects soil fertility regulation efficiency and fruit tree growth quality4,5.

At present, efficient and precise fertilization has become an important development direction for the application of organic fertilizers in orchards6, and fertilization accounts for a large proportion of orchard labor input7,8. However, two major difficulties remain. The first is the lack of efficient and precise mechanized methods for organic fertilizer application. Traditional methods are either extensive with low fertilizer use efficiency, or involve multiple procedures that are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and costly9. The commonly used strip trench fertilization method can improve fertilizer efficiency to some extent, but the separate processes of trenching, fertilization, and backfilling rely heavily on manual labor, resulting in low efficiency and high costs10. The second difficulty is the shortage of efficient and precise mechanized equipment for organic fertilizer application11,12. Orchards are characterized by narrow working spaces and large fertilizer demand, but the range of suitable machinery is limited13,14, with only small-scale spreaders and trenching machines currently available.

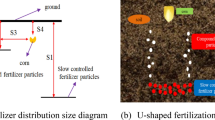

The commonly used trench fertilization methods in orchards include ring trenching, strip trenching, and pit fertilization15,16. Ring trenching ensures relatively uniform fertilizer distribution and higher efficiency, but it risks damaging major roots. Strip trenching is the most efficient method, but it results in low fertilizer utilization and is difficult to perform continuously in the hilly terrain of Southwest China. In contrast, pit fertilization causes minimal root damage17 and allows flexible arrangement of the number and position of pits, thereby improving uniformity. This feature makes pit fertilization particularly suitable for orchards in the hilly regions of Southwest China, where land is fragmented, slopes are steep, and mechanical operating space is limited. Among fertilization devices, grooved-wheel distributors are widely applied due to their simple structure, convenient operation, versatility, and low cost. Based on these considerations, pit fertilization was selected as the operational basis of this study, and a grooved-wheel fertilizer discharge device for pit fertilization machines was proposed to achieve efficient and precise application of powdered organic fertilizers in hilly orchards.

Currently, the major mechanized methods for granular fertilizer application include fluted roller distributors and centrifugal disc spreaders18, with the primary design objectives being to ensure accurate fertilizer dosing and uniform distribution19,20. For the former, Song et al.21 arranged the outer fluted plates in a staggered manner to achieve semi-continuous fertilization, and realized variable application by adjusting the opening size of the fertilizer baffle. Liu et al.22 and Zhang et al.23 improved the structure of the outer fluted roller by adopting herringbone, inclined, and helical arrangements. The helical fluted roller, in particular, achieved continuous fertilization, with the fertilizer rate controlled by adjusting roller speed and outlet size. Gao et al.24 attempted intermittent fertilization through reciprocating opening and closing of the baffle, but found that the fertilizer rate could not be precisely controlled. These improvements enhanced continuity and partially enabled variable application, but precise control remains a challenge.

For centrifugal disc spreaders, Przywara et al.25 analyzed the effects of disc rotational speed, feeding position, and vane angle on the spatial distribution of fertilizers, and showed that modifying these parameters could adjust the spreading range. Yang et al.16 proposed an innovative subsoiling and fertilization machine design based on IFR and SLP theory, which integrated a multi-link hole-making mechanism, a gas-explosion loosening device, and a precision fertilization unit. Fertilizer was discharged to the pit bottom using an auger after loosening the soil by gas explosion. Hu et al.26 and Yuan et al.27 applied the siphon principle, in which changes in airflow velocity at a narrow outlet were used to draw and discharge fertilizers, achieving metering control by regulating airflow speed. Overall, these devices remain inadequate for powdered organic fertilizers in hilly orchards, facing challenges such as clogging, insufficient precision, and limited adaptability. Therefore, it is necessary to develop compact, precise, and adaptable fertilization devices tailored to the characteristics of hilly orchards.

In this context, this study designed a grooved-wheel fertilizer discharge device specifically for powdered organic fertilizers. The device utilizes the intermittent motion characteristics of the grooved-wheel mechanism to achieve lateral fertilizer throwing. A RecurDyn–EDEM coupled simulation approach was applied to optimize key parameters. The effects of dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle on fertilizer application rate, particle trajectories, and landing positions were investigated to identify the causes of fertilizer particle loss. Finally, field experiments were conducted to validate the accuracy of the simulation model.

Methods

Structural design and working principle

To meet the mechanization requirements of orchards in the hilly regions of Southwest China and the demands of modern agricultural technology, a portable and integrated pit-digging and fertilization machine was developed. The equipment integrates a pit-digging unit, a fertilization unit, and an automatic lifting device, and is equipped with a control system based on an STM32 microcontroller. This configuration enables automated pit-digging, fertilization, and backfilling operations. Compared with conventional fluted-roller fertilizer spreaders, the proposed design improves fertilization accuracy under hilly orchard conditions.

The fertilization unit mainly consists of a servo motor, a grooved-wheel mechanism, a fertilizer discharge wheel, and a fertilizer tank, as shown in Fig. 1. The structural parameters of the grooved-wheel mechanism directly influence the fertilizer throwing distance, while the scraper on the discharge wheel has a decisive effect on the fertilizer spreading quality. To address the problem of air resistance inside the fertilizer grooves during filling, small holes were added at the scraper bottom to provide airflow diversion. In order to avoid clogging when handling powdered organic fertilizers, each groove on the discharge wheel was independently arranged. The groove volume and diameter were designed to determine fertilizer discharge efficiency. Once the pit-digging process is completed, the fertilization unit is automatically activated. The driving motor transmits power through the output shaft to rotate the dial plate, and the intermittent motion characteristics of the grooved-wheel mechanism are utilized to achieve directional fertilizer throwing. The operation automatically terminates once the target fertilization amount is reached.

According to agronomic requirements for pit-digging fertilization, the fertilizer depth should preferably be within 20 cm28,29, with a single-pit fertilization rate of 1.25 kg. Given the bulk density of organic fertilizer (600 kg/m³), the required fertilization volume per pit is approximately 2000 cm³.

Structural schematic diagrams of the orchard pit-digging and fertilizing device. A, Schematic diagram of the orchard pit-digging and fertilizing device. (1) Pit-Digging Unit; (2) Automatic Lifting Mechanism; (3) Fertilization Device. B, Structural diagram of the fertilization device. (1) Grooved Wheel Mechanism; (2) Motor; (3) Fertilizer Discharge Wheel; (4) Fertilizer Hopper.

Structural design

Parameters of the grooved wheel mechanism

Structural Parameters and Kinematic Characteristics of the Grooved Wheel Mechanism. The primary structural parameters of the grooved wheel mechanism are the number of grooves on the grooved wheel (z) and the number of circular pins on the dial plate (K). Different combinations of groove numbers and pin numbers significantly influence the operational characteristics and motion stability of the mechanism, as shown in Fig. 2. When the number of grooves (z) is 4 and the number of circular pins (K) is 1, the motion characteristic coefficient of the grooved wheel mechanism is 0.25.

In Fig. 2, let the angles between the positions of the dial and the grooved wheel relative to the centerline be denoted as \({\varphi _1}\) and \({\varphi _2}\), respectively. Angles \({\varphi _1}\) and \({\varphi _2}\) are defined as positive within the pin engagement zone and negative within the pin disengagement zone. Let rx represent the distance O2A from the pin to the rotational axis of the grooved wheel. The relationship among these three variables is given by Eq. (1).

Let \(\frac{R}{L}=\lambda\). Substituting this value into Eq. (1), the resulting expression is shown in Eq. (2).

Differentiating Eq. (2) with respect to time and substituting \(\frac{{d{\varphi _2}}}{{dt}}={\omega _2}\)and \(\frac{{{d^2}{\varphi _2}}}{{d{t^2}}}={\alpha _2}\), the resulting expression is presented in Eq. (3).

where:

\({\omega _2}\) — angular velocity of the grooved wheel, in °/s;

\({\alpha _2}\)— angular acceleration of the grooved wheel, in °/s².

As shown in Eq. (3), when the angular velocity of the dial remains constant, the variation in the angular velocity and angular acceleration of the grooved wheel is determined by the number of grooves z. When z = 4, the angular velocity and angular acceleration of the grooved wheel are illustrated in Fig. 3.

In summary, the transmission structure of the fertilization device is designed as a grooved wheel mechanism to achieve intermittent fertilization at fixed points. By leveraging the motion characteristics of the grooved wheel mechanism, long-distance lateral spreading of fertilizer is effectively realized.

Kinematic analysis of fertilizer particles during the discharge process

By analyzing the motion of fertilizer particles, the key parameters affecting the discharge performance of the fertilization device can be identified. The powdered organic fertilizer is treated as discrete particles, and the entire discharge process—from contact with the grooved wheel to particle ejection—is divided into three stages: filling, feeding, and throwing.During the filling stage, the fertilizer particles are mainly loaded into the grooves under the influence of gravity and the vibrations generated by the gasoline engine during operation. For the feeding and throwing stages, a Cartesian coordinate system XY is established, where X represents the radial direction and Y the tangential (circumferential) direction, to analyze the forces acting on fertilizer particles at the contact point.According to D’Alembert’s principle, the inertial force F is applied to the particle during the analysis. The corresponding force diagram is shown in Fig. 4.

Kinematic Analysis of Fertilizer Particles During the Feeding Stage of the Grooved Wheel. During the feeding stage, the fertilizer particles are driven by the scraper and follow a circular trajectory along with the rotation of the grooved discharge wheel. The primary forces acting on the particles include the inertial force \({F_i}\), the centrifugal force \({F_c}\), and the frictional force \({F_f}\). The corresponding force analysis is as follows:

Where:

m— mass of the fertilizer particles, in kg;

\(\alpha\)— angular acceleration of the grooved discharge wheel, in rad/s²;

\(\mu\)— coefficient of friction between the fertilizer particles and the grooved wheel;

\(\omega\)— instantaneous angular velocity of the grooved discharge wheel, in rad/s;

\(R'\)— distance from the particles to the center of rotation, in meters.

At this stage, the velocity of the particles gradually increases with the rotation of the grooved discharge wheel. Since the initial velocity of the particles is 0, their velocity during the feeding process can be expressed as:

As shown in Eq. (6), the fertilizer particles in transit reach a state of equilibrium under the combined action of centrifugal force and the supporting force from the housing, resulting in no radial displacement. In the tangential direction, the particles are pushed by the discharge scraper and move along the circular path. The motion of the particles is primarily influenced by inertial force, which increases as the radial distance increases.

Kinematic Analysis of Fertilizer Particles During the Throwing Stage of the Grooved Wheel. When the fertilizer particles rotate with the grooved discharge wheel to the discharge outlet, they are ejected from the groove under the combined action of tangential force and inertial force. The moment the particles leave the edge of the discharge outlet is defined as the initial state of the throwing stage. At the instant of ejection, the particles are influenced by gravity and air resistance. The motion equation is expressed as Eq. (7):

Where:

Where:

\(\vec {r}\)— displacement of the particle, in meters (m);

\({\vec {F}_g}\) — gravitational force acting vertically downward, in newtons (N);

\({\vec {F}_d}\)— air resistance, acting in the direction opposite to the particle’s velocity, in newtons (N).

At this moment, the velocity of the particle is given by:

After being ejected, the fertilizer particles are influenced by gravitational acceleration in the vertical direction, causing them to first ascend and then descend. As shown in Eq. (9), the initial velocity of the ejected particles is affected by the instantaneous angular velocity, while the direction at the moment of release is determined by the scraper blade inclination angle\(\psi\).

In summary, the key factors influencing the motion of fertilizer particles are the rotational speed of the dial in the grooved wheel mechanism and the inclination angle of the scraper blades. These factors have a direct impact on the fertilization performance of the device. In the following stages, simulation experiments will be conducted to determine the optimal operating and structural parameters.

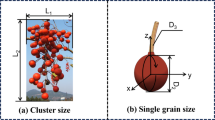

Design of the grooved discharge wheel

The number of grooves on the grooved discharge wheel corresponds to the grooved wheel mechanism and consists of four equally divided fan-shaped grooves, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Using a grooved wheel intermittent motion mechanism, the fertilization efficiency is related to the dial rotational speed and the size of the grooves. The single discharge volume Q0 can be expressed as:

Where:

r1— radius at the bottom of the groove, in meters (m);

r2— radius at the top of the groove, in meters (m);

b— width of the groove, in meters (m);

t— thickness of the scraper blade, in meters (m);

\(\rho\)— bulk density of the fertilizer, 600.17 kg/m³;

\(\varphi\)— groove filling coefficient, 0.9.

As shown in Eq. (10), numerous parameters influence the single discharge volume. Considering the structural layout and installation position of the fertilization device, as well as the fertilization requirement of 1.25 kg per pit, the top radius of the groove r2 is set to 100 mm, the groove width b to 200 mm, and the bottom radius r1 to 73 mm. Under these conditions, the volume of a single groove in the discharge wheel is 733 cm³, resulting in a single discharge amount Q of 636 g. Thus, two discharges are sufficient to meet the fertilization demand per pit. When the scraper pushes the particles to the discharge outlet, the rotational speed of the grooved discharge wheel reduces to zero. Subsequently, the fertilizer particles are primarily influenced by inertia and gravity. Gravity acts vertically downward, while the direction of inertia, besides the tangential force, is also affected by the inclination angle of the grooved wheel’s scraper. Treating the particles within the groove as a whole, the lateral fertilization range and particle trajectories during the side fertilization process of the hole-digging device are illustrated by the shaded area in Fig. 6.

The ejection trajectory of the particles is related to both the magnitude and direction of the initial velocity. The magnitude of the initial velocity is determined by the rotational speed, while its direction is influenced by the scraper blade angle and the position of the discharge outlet. When the scraper blade forms a certain angle with the radial direction, the force exerted by the scraper no longer acts purely radially, altering the velocity and direction at which particles leave the discharge outlet of the grooved wheel.

Let the initial velocity of the particle upon leaving the discharge outlet be\({v_0}\) and the angle between the scraper blade and the radial direction be \(\psi\). The positive direction is defined along the tangential movement direction; the opposite direction is negative. Air resistance is considered, and the initial position is set at the origin. The particle’s initial ejection angle at the moment of leaving the outlet is 45°. Due to the scraper blade inclination, the initial angle relative to the horizontal direction is given by:

The velocity of the particle upon leaving the scraper can be decomposed into two components: horizontal and vertical.

Due to the presence of air resistance, the motion equation of the particle in the horizontal direction is:

Where:

\({C_d}\)— air resistance coefficient.

Under the influence of air resistance and gravity, the particle motion equation in the vertical direction is given by:

Where:

g— gravitational acceleration, 9.8 m/s2.

The discharge outlet of the fertilization device is positioned at a height H of 200 mm above the ground, with the shortest distance L to the pit being 180 mm. Given the pit diameter D of 300 mm, the maximum horizontal distance reaches 480 mm. Considering the kinematic characteristics of the grooved wheel mechanism, the preliminary rotational speed range is set between 50 ~ 90 r/min, and the angle of the discharge wheel scraper is adjustable within − 30 ~ 30°. Based on the maximum output torque and rotational speed of the grooved wheel, and accounting for the relatively high friction coefficient of the powdered organic fertilizer, the motor model for the fertilization device is selected as LC86H2150, which provides an output torque of 12 N·m.

Simulation study based on RecurDyn-EDEM coupling

In this study, a coupled RecurDyn-EDEM simulation model was established, using fertilizer application rate as the experimental metric to investigate the effects of dial rotational speed and scraper blade inclination on the application rate, aiming to optimize both operational and structural parameters. The discrete element simulation of the fertilization process was performed after the hole-digging operation was completed. Accordingly, in the EDEM software, the discrete element model of the hole-digging operation was exported at time zero as input data to prepare for subsequent fertilization modeling. Due to the unique kinematic characteristics of the grooved wheel mechanism, the mechanism’s motion was modeled in RecurDyn. Since the primary objective was to observe the fertilizer discharge performance, the geometries of the fertilization device were treated as rigid bodies during the coupled simulation. The motion and contact-configured components in RecurDyn were exported in the form of Walls, which were then imported into EDEM. The relative position of the fertilization device to the soil groove was adjusted within EDEM before initiating real-time feedback simulations, as illustrated in the Fig. 7.

The fertilizer discharge device is made of SUS304 stainless steel, with a Poisson’s ratio of 0.29, an elastic modulus of 193 GPa, and a density of 8000 kg/m³30. The simulation parameters are shown in Table 1.

Experimental design

Single-factor influence analysis

To investigate the relationships between the influencing factors of the fertilization device and the evaluation index, the dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle were selected as test factors, while the fertilizer placement rate was used as the evaluation index. Based on the theoretical analysis of the fertilization device and agronomic requirements, the value ranges of the factors for single-factor experiments were determined, as shown in Table 2. In the coupled simulation tests conducted using RD–EDEM software, one factor was varied while the other was fixed at the zero level.

By varying the values of each experimental factor, the influence of different parameters on the fertilizer application rate was investigated. Based on the simulation results, the variation curves of the proportion of fertilizer mass deposited at the bottom of the planting hole during the discharge process were plotted. These curves reflect the effectiveness of fertilizer delivery under different parameter combinations and provide a visual basis for assessing the uniformity and precision of fertilizer placement. As shown in Fig. 8, when the scraper blade inclination angle is held constant, the dial rotational speed has a significant influence on the fertilizer application rate. The trend indicates a non-linear relationship: the application rate increases initially with rotational speed and then decreases after reaching a peak. The optimal performance is observed within the speed range of 50–70 r/min. Conversely, when the dial rotational speed is fixed, the effect of the scraper blade inclination angle on the application rate is comparatively moderate. However, a similar trend is observed: the application rate first increases and then decreases as the blade angle changes. The optimal performance is achieved when the blade inclination is between − 30° and 0°.

Simulation test design

According to the interaction effects of dial plate speed (X₁) and scraper inclination angle (X₂) on the fertilizer incorporation rate (R₁), a Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed to determine the optimal operating and structural parameters of the fertilization device. Based on the results of single-factor experiments, the appropriate factor levels were established, as shown in Table 3, and a two-factor, three-level simulation experiment was conducted accordingly.

Bench and field experiment design

Bench and field experiments were conducted in July 2024 at the Scientific Research Experimental Orchard of Sichuan Agricultural University, located in Yucheng District, Ya’an City, Sichuan Province. The bench test of the fertilizer applicator was carried out based on the optimal parameters obtained from the simulation results, with the experimental plan presented in Table 4. The bench test results were compared with the simulation outcomes, and the simulation accuracy was verified by measuring the single-application fertilizer mass.

The field experiment, influenced by ground unevenness and engine-induced vibration, was designed to reflect real operating conditions. The fertilizer applicator’s performance was evaluated by measuring the organic fertilizer application rate under actual working environments, with the experimental plan summarized in Table 5.

Results and discussion

Simulation test results and regression model

Based on the results of the single-factor experiments and the experimental design, a two-factor, three-level simulation experiment was conducted. The experimental scheme and corresponding results are presented in Table 6.

A response surface regression model of the effects of disc rotation speed and scraper inclination angle on the application rate was established using Design-Expert software. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, and the significance level was determined at p < 0.05. The results are shown in Table 7.

he significance of each influencing factor was evaluated through analysis of variance (ANOVA)31. The ANOVA results showed that the overall regression model was significant (Model F = 271.94, p < 0.0001), indicating that the selected variables effectively explained the variation in application rate. The scraper inclination angle (X₂) exhibited a highly significant main effect (F = 518.11, p < 0.0001), and its quadratic term (X₂²) was also highly significant (F = 833.74, p < 0.0001), demonstrating that scraper inclination had a pronounced influence on the application rate. In contrast, the disc rotation speed (X₁) and its quadratic term were not significant (F = 2.61, p = 0.1502; F = 2.31, p = 0.1723, respectively), and the interaction between X₁ and X₂ was also insignificant (F = 0.128, p = 0.7311). These statistical results indicate that, within the experimental range (45.86–74.14 r/min), the scraper inclination angle was the dominant factor affecting the application rate, whereas the effect of disc rotation speed was relatively weak or limited by the narrow range of test conditions. The scraper inclination directly changes the particle velocity and direction at the outlet, thereby exerting a strong influence on the throwing trajectory and velocity32, which explains its high statistical significance. The non-significance of X₁ may be attributed to the relatively narrow speed range (45.86–74.14 r/min) used in this study33, which reduced its contribution to the total variation. In future work, the effect of X₁ will be further examined by expanding the speed range.

Based on the regression analysis, a quadratic regression model for the fertilizer placement rate (R₁) was established. Non-significant terms in the model were removed for optimization, and the resulting equation is given in Eq. (14).

According to the regression model and the analysis results, the response surface of the interaction effects was plotted, as shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9 illustrates the interaction effects of dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle on the fertilizer placement rate. The interaction between dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle had only a minor influence on the placement rate, while the overall trends of the two factors were generally consistent with those observed in the single-factor experiments. In both cases, the placement rate initially increased and then decreased. When the dial plate speed was fixed, the optimal placement rate was achieved with a scraper inclination angle between − 24° and − 6°. Conversely, when the scraper inclination angle was fixed, the optimal placement rate was obtained at a dial plate speed of 60–70 r/min.

According to the agronomic requirements of orchard planting and management, fertilizer should be delivered to the bottom of the pit as much as possible. Since the effects of the two experimental factors on the evaluation index followed essentially the same pattern, the fertilizer placement rate was selected as the objective function. An optimization design was then conducted by treating dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle as independent variables, and the mathematical model is expressed as follows:

By comprehensively considering the effects of the two parameters on the evaluation index, optimization was performed to obtain the optimal parameter combination. The results showed that the dial plate speed of 64.3 r/min and the scraper inclination angle of − 17.3° yielded a single fertilization amount of 637.98 g, with a corresponding fertilizer placement rate of 97.57%.

Analysis of fertilizer particle trajectories and landing positions

To identify the locations of fertilizer particle loss during the fertilization process, the cross-section (XOZ) of the fertilizer applicator was divided into three circumferential regions with radii of 73–82 mm, 82–91 mm, and 91–100 mm from the center of rotation of the fertilizer discharge fluted roller, designated as the first, second, and third circumferential regions, respectively. Similarly, three width regions were defined at distances of 0–40 mm, 40–80 mm, and 80–120 mm from the fertilizer outlet, designated as the first, second, and third width regions, respectively. A statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate the fertilizer deposition rate across different regions, as illustrated in Fig. 10. The figure reveals distinct distributions of landing positions for fertilizer particles in regions of varying circumferential and radial widths. The results revealed that particles not deposited at the bottom of the pit were mainly located in the first and third width regions of the third circumferential zone, whereas nearly all particles deposited at the pit bottom were concentrated in the second circumferential and second width regions. This distribution pattern s attributed to the relatively low initial velocities of particles in the first width region, and the trajectory deflection of those in the third width region due to obstruction by preceding particles. To further investigate this behavior, particle motion trajectories were analyzed, as shown in Fig. 11.

The motion trajectory of fertilizer particles was analyzed, and the resulting particle trajectories during the fertilization process are illustrated in Fig. 11. The throwing trajectories of fertilizer particles in different regions were compared. As shown in Fig. 11a, in the circumferential direction, particles in the third circumferential region exhibited greater velocity fluctuations compared to those in the first and second regions. In contrast, particles in the second circumferential region displayed more uniform and concentrated velocities after being ejected, relative to those in the first and third regions. In the width direction, as illustrated in Fig. 11b, particles in the second width region demonstrated higher velocities and more concentrated trajectories than those in the first and third width regions. Conversely, particles in the first width region exhibited greater velocity disturbances and more irregular trajectories compared to those in the second and third width regions.

In summary, the particles in the second width region of the second circumferential zone were more effectively deposited at the bottom of the pit. This behavior can be attributed to the tangential acceleration generated by the groove wheel speed, scraper inclination, and discharge outlet position18. Furthermore, particles in this region experienced less obstruction from those ahead, allowing them to move along a more concentrated trajectory into the pit. In contrast, in the first and third width regions of the third circumferential zone, particle trajectories were more dispersed, leading to higher particle loss. This was primarily caused by the combined effects of increased air resistance and deflection at the groove outlet34, which altered the particle motion trajectories.

As shown in Figs. 10 and 11, the interaction between circumferential and width-based regional divisions plays a dominant role in shaping the overall deposition pattern. In the second circumferential region and the second width region, the acceleration reaches its maximum, and the particles experience minimal obstruction from adjacent particles. The overlap of these two regions forms a concentrated deposition zone, where particles gain maximum kinetic energy and maintain stable trajectories. In contrast, deviations occurring in the outer circumferential regions lead to increased scattering losses. Similar localized deposition behavior in fertilizer particle discharge was also reported by Hu et al.35 and Dun et al.36, confirming that tangential acceleration stability is a key factor in controlling discharge precision.

To minimize particle losses in the peripheral zones and in the first and third width regions, future optimization may involve reducing the outlet width of the discharge groove wheel, refining the scraper curvature, and introducing adjustable air-guiding channels to stabilize particle ejection trajectories.

Bench test

According to the agronomic requirements of orchard management, a bench test of the fertilization device was conducted to measure the fertilizer discharge, as shown in Fig. 12. A cardboard box was used to completely collect the discharged fertilizer, thereby minimizing environmental interference. Based on the optimal parameters obtained from the simulation, the bench test was carried out with a dial plate speed of 64.3 r/min and a scraper inclination angle of − 17.3°. The experimental results were compared with the simulation results, and the accuracy of the simulation was verified by measuring the single fertilization amount.

To reduce experimental error, ten fertilization discharge tests were conducted, and the average value of the measured fertilization amount was taken. The results are presented in Table 8. The experimental results showed that the error between the bench test and the simulation under the optimal parameters was 2.11%, thereby verifying the accuracy of both the simulation and the structural design.

Field experiment

The bench test of the fertilization device verified the accuracy of the fertilizer dispenser’s structural design. Subsequently, a field experiment of the fertilization machine was conducted to measure the fertilizer placement rate of organic fertilizer under actual working conditions. The field test, shown in Fig. 13, was able to reflect real operating conditions due to ground unevenness and engine-induced vibrations37. The fertilizer collected at the pit bottom was measured, with ten replications averaged. The results are presented in Table 9, showing that the mean single fertilization amount at the pit bottom was 633.43 g, corresponding to a fertilizer placement rate of 96.87%. This meets the technical requirements of orchard pit-digging fertilization machines.

Conclusion

This study focused on the fertilization device, analyzing the fertilizer particle trajectories and distribution during operation, as well as the fertilizer placement rate in orchard pit fertilization. To reduce air resistance inside the discharge grooves during fertilizer filling, small holes were introduced at the bottom of the scrapers for airflow diversion, and each groove of the discharge wheel was arranged independently. In addition, simulation experiments were conducted to analyze the effects of dial plate speed and scraper inclination angle on the placement rate. The motion trajectories and landing positions of fertilizer particles during operation were further investigated to identify the sources of particle loss. Finally, the model was validated through field experiments, and the following conclusions were drawn:

(1) To achieve precision fertilization, kinematic analysis of fertilizer particles during the discharge process identified the dial plate speed of the wheel mechanism and the scraper inclination angle of the discharge wheel as the key influencing factors.

(2) In the single-factor experiments, when the scraper inclination angle was held constant, the dial plate speed had a significant effect on the fertilizer placement rate, which initially increased and then decreased with increasing speed. Based on the simulation experiments, with the placement rate as the target value, the optimal parameter combination was obtained as a dial plate speed of 64.3 r/min and a scraper inclination angle of − 17.3°, yielding a single fertilization amount of 637.98 g and a placement rate of 97.57%.

(3) By dividing the fertilizer particles into nine regions according to their radial distance and distance from the discharge outlet, it was found that particles in the second circumferential and second width regions received the maximum acceleration from the discharge wheel, resulting in more concentrated trajectories and improved deposition at the pit bottom. Comparison between the simulation and bench test results under the optimal parameters showed an error of 2.11%, confirming the accuracy of both the simulation and the structural design, and indicating that the proposed discharge device can significantly improve fertilization accuracy. However, due to equipment and time limitations, validation was performed only under the single optimal parameter combination. Future work will expand the validation under multiple working conditions to comprehensively confirm the accuracy of the simulation model.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Request for more details to the corresponding author.

References

National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook 2022 (China Statistics, 2023).

Hu, Y., Chen, X. & Qi, C. J. Research on the changes of china’s fruit planting distribution and its influence effect: based on the perspective of price changes of rural labor. World Reg. Stud. 32 (9), 93–108 (2023). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Ladon, T. et al. Optimizing Apple orchard management: investigating the impact of planting density, training systems and fertigation levels on tree growth, yield and fruit quality. Sci. Hortic. 334, 113329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113329 (2024).

Zhou, X. Z. et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the furrow shape in orchards using a low-cost lidar. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1201994. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1201994 (2023).

Wu, X. M. et al. Improvement design and experiment of a small deep-placement fertilizer applicator. Eng. Agric. Environ. Food. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eaef.2019.12.011 (2020).

Schepers, J. Precision agriculture for sustainability. Precis Agric. 20 (1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-018-09627-5 (2019).

Li, X. G. & Huo, X. X. Agricultural labor markets and the inverse plot size–productivity relationship: evidence from china’s Apple growers. Rev. Dev. Econ. 26 (4), 2163–2183. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12920 (2022).

Tukey, L. D. Capital investment in labor and machines for an economical system of fruit production. Acta Hortic. 103, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1979.103.3 (1979).

Hang, C. G. et al. Discrete element simulations and experiments of soil disturbance as affected by the Tine spacing of subsoiler. Biosyst Eng. 168, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.03.008 (2018).

Heidarisoltanabadi, M. et al. Determination of the most appropriate fertilizing method for Apple trees using multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approaches. Food Sci. Nutr. 12 (2), 1158–1169. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.3831 (2023).

Liang, X. D. et al. Design and parameters optimization for solid organic fertilizer loading and spreading machines based on the discrete element method. J. Comput. Methods Sci. Eng. 24 (6), 3477–3492. https://doi.org/10.1177/14727978241299185 (2024).

Zhang, H. J. et al. Design and experiment of orchard double row ditching-fertilizer machine with automatic depth. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 52 (1), 62–72 (2021). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zheng, Y. J. et al. Review on technology and equipment of mechanization in hilly orchard. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 51 (11), 1–20 (2020). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Fangueiro, D., Alvarenga, P. & Fragoso, R. Horticulture and orchards as new markets for manure valorisation with less environmental impacts. Sustainability 13 (3), 1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031436 (2021).

Vadivel, R. et al. Effect of pit and soil types on growth and development, nutrient content and fruit quality of pomegranate in the central Deccan plateau region, India. Sustainability 16 (18), 8099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16188099 (2024).

Yang, T. et al. Innovative design of fruit tree deep loosening fertilizer applicator based on TRIZ theory. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 44 (10), 65–71 (2023). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Mollapour, S., Kalantari, D. & Rajabi Vandechali, M. Design, development and evaluation of a new motorized hydraulic hole-digger for spot treatment. J. Agric. Mach. 8 (2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.22067/jam.v8i2.64470 (2018).

Sun, X. B. et al. Particle motion analysis and performance investigation of a fertilizer discharge device with helical staggered groove wheel. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108241 (2023).

Sugirbay, A. M., Zhao, J., Nukeshev, S. O. & Chen, J. Determination of pin-roller parameters and evaluation of the uniformity of granular fertilizer application metering devices in precision farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 179, 105835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105835 (2020).

Sun, J. F. et al. Mechanical properties of the grooved-wheel drilling particles under multivariate interaction influenced based on 3D printing and EDEM simulation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 172, 105329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105329 (2020).

Song, C. C. et al. Optimization of the groove wheel structural parameters of UAV-based fertilizer apparatus. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 37 (22), 1–10 (2021). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Liu, H. N. et al. Design and experiment of screw-type feeding device of air-assisted centralized fertilizer application device. J. China Agric. Univ. 26 (8), 150–161 (2021). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang, J. Q. et al. Influence of control sequence of spiral fluted roller fertilizer distributer on fertilization performance. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 51, 137–144 (2020). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Gao, J. et al. Development and field performance evaluation of hole-fertilizing planter and dynamic alignment control system for precision planting of corn. Precis Agric. 24, 1241–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-023-09988-6 (2023).

Przywara, A. The impact of structural and operational parameters of the centrifugal disc spreader on the Spatial distribution of fertilizer. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia. 7, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaspro.2015.12.021 (2015).

Hu, C., Fang, X. L. & Shi, Y. J. Design and test of pneumatic fertilizer apparatus in paddy field. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 43 (1), 14–19 (2022). (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yuan, W. S. et al. Influencing factors of the distribution accuracy and the optimal parameters of a pneumatic fertilization distributor in a fertilizer applicator. Agronomy 12 (9), 2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092222 (2022).

Liu, S. X. et al. Review on technology and equipment of mechanization in hilly orchard. J. Chin. Agric. 51 (S2), 99–108 (2020).

Zeng, S. C. et al. Nitrogen and phosphorus runoff losses from orchard soils in South China as affected by fertilization depths and rates. Pedosphere 18 (1), 45–53 (2008).

Pyo, C. et al. A study to derive equivalent mechanical properties of porous materials with orthotropic elasticity. Materials 14 (18), 5132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14185132 (2021).

Shi, Y. Y. et al. Numerical simulation and field tests of minimum-tillage planter with straw smashing and strip laying based on EDEM software. Comput. Electron. Agric. 166, 05021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.105021 (2019).

Xie, Y. T. et al. Effect of angle between center-mounted blades and disc on particle trajectory correction in side-throwing centrifugal spreaders. Agriculture 15, 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15131392 (2025).

Serdar, C. C., Cihan, M., Yücel, D. & Serdar, M. A. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 31 (1), 010502. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2021.010502 (2021).

Bangura, K. et al. Simulation analysis of fertilizer discharge process using the discrete element method (DEM). PLOS ONE. 15 (7), e0235872. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235872 (2020).

Hu, D. B. et al. Performance analysis and experiment of variable fertilizer spreader based on EDEM. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 44 (2), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.13427/j.cnki.njyi.2022.02.031 (2022).

Dun, G. Q., Sheng, Q. B. & Ji, X. X. Parameter optimization of the Notched blade spiral fertilizer discharger for pineapple orchards based on DEM. Front. Mech. Eng. 11, 1535013. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2025.1535013 (2025).

Gil, E. et al. Field validation of dosaviña, a decision support system to determine the optimal volume rate for pesticide application in vineyards. Eur. J. Agron. 35 (1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2011.03.005 (2011).

Funding

This research was supported by the Listing Project of Rural Revitalization Research Institute of Sichuan Tianfu District (XZY1-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZR.C. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing -review & editing; X.T. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation; ZF.C. statistics; H.Z. Software, Validation; J.H. Formal analysis; Y.L. Investigation; L.C. Funding acquisition, Resources, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Tan, X., Chen, Z. et al. Coupled RecurDyn-EDEM simulation and experimental analysis of a precision fertilization device. Sci Rep 15, 42167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26063-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26063-4