Abstract

Under the “dual carbon” goal, the mismatch between the intermittent nature of wind-solar power generation and the stable energy demand of oil wells hinders efficient green energy utilization in oilfields, leading to low green electricity consumption, high curtailment rates, and poor economic benefits. To address this challenge, an optimization approach for oil well operation scheduling is proposed, which couples photovoltaic power fluctuations with the characteristics of intermittent pumping technology. Firstly, a multiobjective optimization model was developed to minimize grid electricity consumption per unit of liquid production and maximize the share of green electricity. The on-off schedule was mapped into a constrained binary sequence using a run-length encoding to reducing the solution space. Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was improved to increase both accuracy and convergence speed by introducing: (1) dual-mode initialization strategy guided by historical operating schedules and photovoltaic fluctuations. (2) a key-gene-preserving crossover operator to retain high-matching time segments; and (3) a peak-valley-guided mutation strategy to enable dynamic pruning of the solution space and goal-directed optimization. Case studies showed that the proposed method doubled green electricity consumption under stable production conditions, reduced grid electricity consumption per unit liquid by 41.67%, improved computational efficiency by two to three orders of magnitude, and enhanced the solution accuracy by 26.69%, indicating strong practical applicability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a core carrier of traditional energy production and consumption, China’s oil and gas field operations account for approximately 20.65% of the total electricity consumption in the mining industry1. The wide geographical distribution of field facilities, each single-well site occupying an average area of no less than 1,300 \(\:{m}^{2}\)2, combined with well-developed grid infrastructure, offers a unique spatial-energy coupling advantage for the distributed deployment of renewable energy systems such as wind, solar, and geothermal systems. Promoting the construction of renewable energy projects can enable the substitution of conventional electricity with green electricity for production purposes, thereby enhancing energy conservation and emission reduction performance and supporting the oilfield sector’s efforts to achieve the national “dual carbon” targets3,4,5. Chinese oilfield enterprises are accelerating green electricity deployment6. The integration of green electricity into the power grid intensifies the grid’s regulatory burden, has attracted scholarly attention from the supply side, including studies on grid energy efficiency7, distribution system optimization8, grid stability9, and the formulation of tiered electricity pricing10. Nevertheless, in the absence of a fundamental shift in end-use electricity consumption patterns, it remains challenging for green electricity to serve as an effective substitute for conventional energy. For oil enterprises, the deployment of self-owned green power projects is constrained by their potential impacts on the grid system. Currently,, the overall economic viability of such projects remains limited due to low onsite consumption, low feed-in tariff for green electricity and high wind and solar curtailment rates in certain regions11,12. Therefore, improving the self-consumption ratio of green electricity and optimizing consumption models, such as through energy storage systems or microgrids, has become critical to enhancing the economic performance of green power projects in the oilfield industry.

Approximately one-third of electricity consumption in oilfield production is attributed to artificial lift systems13. Compared with continuously operating wells, low-producing and low-efficiency wells that operate intermittently exhibit a more interruptible load characteristics. By dynamically adjusting their operating schedules, the spatiotemporal distribution of load can be shifted to accommodate the intermittent output of green electricity, thereby improving source-load coordination efficiency in scenarios with highly fluctuating power supplies. Existing studies on intermittent pumping schedule optimization mainly follow two technical routes: one based on dynamic liquid level and the other based on well on-off period as the decision variable for intermittent operation. A detailed literature comparison is shown in Table 1. These studies primarily focused on conventional oilfield production scenarios with stable grid energy supply, where operating schedule optimization was typically determined along two dimensions of on-off duration or liquid level, and the system ran in periodic alternation according to the optimized schedule. In such scenarios, the real-time requirement for optimization algorithms was relatively low.

However, directly applying conventional methods to renewable energy scenarios with fluctuating power supply often leads to mismatches between load demand and source-side supply, resulting in insufficient green electricity utilization, higher curtailment rates, and weaker source-load matching, which ultimately undermine project economics. This limitation arises primarily because conventional control strategies fail to adequately capture the dynamic and uncertain nature of fluctuating energy, thereby hindering effective temporal matching between supply and load. To address this challenge, it is essential to develop load optimization approaches tailored to the fluctuating characteristics of renewable energy supply. Such approaches can enhance green electricity utilization and improve system operational efficiency, thereby strengthening source-load matching and maximizing the economic and environmental benefits of renewable energy.

Several scholars have investigated the optimization of intermittent pumping schedules under fluctuating energy supplies. Sun et al. (2023)19 investigated the optimization of intermittent pumping schedules for individual wells and developed a model with a 30-minute temporal resolution. The study focused on day-level on-off schedule optimization under two typical scenarios: tiered electricity pricing and photovoltaic (PV) power generation. The problem was solved via NSGA-II, with 48 decision variables, a population size of 2000, and 500 generations. Wang et al. (2025)20 addressed the optimization of intermittent pumping schedules for well clusters powered by wind-solar-storage microgrids. They proposed a scheduling optimization method based on a hybrid intelligent algorithm and established a model with a 1-hour temporal resolution and a 24-hour planning horizon. To enhance algorithm convergence, improvements were made to the inertia weight and learning factors of the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, as well as to the adaptive crossover probability and dynamic mutation rate of the genetic algorithm (GA).

These studies formulated the intermittent pumping schedule optimization problem as a 0–1 integer programming model, where the solution space exhibits double-exponential growth with finer time granularity and an increasing number of wells. Although improvements in algorithmic parameters (e.g., inertia weights, learning factors) have been employed to enhance search efficiency, two fundamental challenges remain. First, the proliferation of infeasible solutions: many candidate solutions generated during the search process violate engineering constraints such as dry pumping or minimum/maximum allowable continuous operating or stoppage duration, degrading solution quality and undermines engineering reliability. Second, the curse of dimensionality: the high-dimensional search space deteriorates convergence characteristics, often leading to premature convergence and a greater risk of entrapment in local optima. As a result, the likelihood of obtaining feasible solutions within limited adjustment cycles decreases, making it difficult for the optimized pumping schedules to dynamically track renewable energy fluctuations, thereby weakening source-load matching and ultimately constraining the overall system performance.

In this study, we investigate the optimization of intermittent pumping schedules for oil wells under PV grid-connection scenarios. A multi-objective optimization model is developed to minimize grid electricity consumption per unit liquid production while maximizing the share of green electricity. To address the challenges of solution space complexity, a run-length encoding scheme is employed to define optimization parameters, and its effect on feasible solution distribution is analyzed. Furthermore, prior knowledge, including PV fluctuation patterns and original pumping schedules, is integrated into the algorithm design, with targeted improvements made to initialization, crossover, and mutation operators. Comparative experiments confirm that the proposed method achieves higher optimization accuracy and efficiency, thereby enhancing the practical applicability of intermittent pumping schedule optimization under renewable energy scenarios.

On-off scheduling model for intermittent pumping wells under grid-connected PV systems

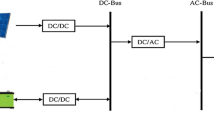

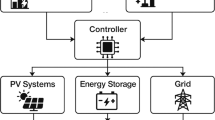

This study investigates the optimization of on-off scheduling for intermittent pumping well systems in scenarios involving grid-connected photovoltaic systems without energy storage, under a renewable-energy-priority supply scheme, as shown in Fig. 1. The system operates with a parallel power supply from both a PV array and the conventional electrical grid. It is designed without energy storage, prioritizing the utilization of green energy from the PV array. When PV power is insufficient, the system automatically switches to grid electricity to ensure continuous operation. Intermittent pumping wells, as critical loads, are required to fulfill the inflexible demand of a minimum daily oil production, while simultaneously possessing the potential for load shifting21. By integrating real-time PV output with load demand, the controller optimizes the on-off scheduling of intermittent pumping wells to achieve source-load matching.

The oil well system is a multi-domain, strongly coupled dynamic system that integrates surface electromechanical equipment, multiphase flow in the wellbore, and reservoir seepage. Its dynamic processes span multiple time scales, ranging from seconds (electromechanical responses) to days (reservoir recovery). Single time-scale modeling presents inherent limitations: a fine-grained second-level scale can capture equipment dynamics but leads to excessive computational costs, whereas a coarse-grained hourly scale sacrifices responsiveness to PV fluctuations. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a multi-time-scale collaborative optimization method. Specifically, system performance evaluation and planning are conducted on a daily scale, while a minute-level scheduling interval is employed to achieve high-precision dynamic matching between PV output and oil well load, thereby effectively balancing computational efficiency and control accuracy. Taking intermittent pumping wells with original pumping cycles not exceeding 24 h as the research object, the relationship between the daily planning cycle and the basic scheduling unit is established as shown in Eq. (1).

where, \(\:\text{T}\) is the planning horizon, min, in this model, \(\:T=1440\:min\), i.e., one day. \(\:{\Delta\:}\text{t}\) denotes the basic scheduling unit, min; in this model, \(\:{\Delta\:}\text{t}=10\:\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}\). \(\:\text{t}\) represents the index of discrete time intervals within the planning horizon; there are \(\:{n}_{t}\) intervals in total.

Optimization parameters

Drawing on the run-length encoding (RLE) technique from data compression algorithms22, the optimization parameters consist of three parts: the initial state, the sequence of 0-run lengths, and the sequence of 1-run lengths (Fig. 2). This method is referred to as the optimization parameter definition and is based on 0–1 run-length encoding (0–1 RLE).

The state of intermittent pumping wells typically alternates between start and stop phases; therefore, given the initial state, the subsequent on-off states of the well can be determined, as defined by Eq. (2).

where, \(\:{\text{S}}_{0}\) denotes the initial state. 1 represents the on and 0 represents the off. If the initial state is 1 (i.e., on), then the subsequent on-off sequence of the well must follow the following pattern: on–off–on… (i.e., 101…).

The sequence of 0-run lengths is defined to represent the durations of stoppage periods, as shown in Eq. (3).

where, \(\:{tc}^{i}\) denotes the length of the i-th 0-run (stoppage duration). \(\:{tc}^{i}\times\:\varDelta\:\text{t}\) represents the continuous stoppage duration. Its minimum value cannot be less than the lower bound of a single well stoppage duration \(\:{\text{T}}_{1,\text{c}}\) to avoid frequent on-off cycles that could reduce equipment lifespan. Its maximum value is the difference between the planning horizon \(\:T\) and the lower bound of a single well operating duration \(\:{\text{T}}_{1,\text{o}}\), ensuring that both start and stoppages occur at least once within the planning horizon. \(\:i\) is the index of the run-length (RL) sequence, with a minimum value of 1, indicating at least one stoppage per planning horizon. \(\:{n}_{s}\) denotes the maximum index of \(\:i\), which corresponds to the ratio of the planning horizon to the sum of the shortest operating duration and stoppage duration, as expressed in Eq. (4).

Similarly, Eq. (5) describes the sequence of 1-run lengths, which represents the durations of the operating periods.

where, \(\:{\text{t}\text{o}}^{\text{i}}\) denotes the length of the i-th 1-run (operating duration). \(\:{\text{t}\text{o}}^{\text{i}}\times\:\varDelta\:\text{t}\) represents the continuous operating duration. Its minimum value must not be less than the lower bound of a single well operating duration \(\:{\text{T}}_{1,\text{o}}\). Its maximum value is defined as the difference between the planning horizon \(\:T\) and the lower bound of a single well stoppage duration \(\:{\text{T}}_{1,\text{c}}\).

The parsing process for the optimization parameters is as follows: first, given the initial state, the alternating on-off sequence of the well is determined. Then, following this sequence, the corresponding run lengths are sequentially extracted from the 0-run length sequence and the 1-run length sequence to construct the on-off schedule. Assuming that the initial state is 1 (i.e., start), the parsing result is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Previous studies19,20,23 have described optimization parameters via binary encoding, referred to as 0–1 state encoding. During the optimization process, the durations of consecutive operating and stoppage periods were accumulated and evaluated to determine whether they satisfy the engineering constraints on minimum continuous operating and stoppage duration. If the constraints are not met, a new solution must be generated.

In contrast, the 0–1 RLE method proposed in the study explicitly defines the allowable range of operating and stoppage durations. This approach internalizes the engineering constraints on continuous operating and stoppage periods, effectively preventing the generation of infeasible solutions and significantly improving both the feasibility probability and optimization efficiency.

Assuming a planning horizon of 24 h and a basic scheduling unit of 10 min, with both the minimum continuous operating and stoppage durations not less than 60 min, the optimization parameters based on 0–1 state encoding are shown in Fig. 4, and the solution space size is \(\:\left|B\right|={2}^{144}\).

The optimization parameters based on the 0–1 RLE are shown in Fig. 5(a). The initial state is 0, indicating a stopped state, which results in a on-off sequence of 010101. First, the value 51 is extracted from the 0-run length sequence, representing 51 basic scheduling units of stoppage, i.e., a stoppage duration of \(\:51\times\:10/60=\)8.5 h. Then, the value 46 is extracted from the 1-run length sequence, indicating 46 units of operation, i.e., an operating duration of \(\:46\times\:10/60\approx\:\)7.67 h. This process is repeated alternately until the cumulative duration of all stoppages and operating durations reaches 144 units. The final state in this example is 1 (i.e., operation) with a duration of 18 units, which is truncated to 17 to ensure that the total duration fits the planning horizon. The decoding process of the optimization parameters is illustrated in Fig. 5(b).

The initial state has two possible values: 0 or 1. Both the 0-run length sequence and the 1-run length sequence contain 12 parameters, each with a value ranging from 6 to 138. Therefore, the size of the solution space is denoted as \(\:\left|\text{E}\right|=2\times\:{133}^{24}\). This structure focuses only on the head portion of the 0–1 run-length sequences whose cumulative length equals 144 (the planning horizon), whereas the remaining tail beyond 144 does not affect the evaluation of the objective function (let the size of this restricted solution space be denoted as \(\:{\text{E}}^{{\prime\:}}\), clearly, \(\:{\text{E}}^{{\prime\:}}\subseteq\:\text{E}\). From the perspective of set inclusion and order of magnitude, \(\:\left|{E}^{{\prime\:}}\right|\le\:\left|E\right|\), and \(\:\left|E\right|\gg\:\left|B\right|\). Since only the head portion of the sequence summing to 144 is relevant, it generally holds that \(\:\left|{E}^{{\prime\:}}\right|\le\:\left|B\right|\), meaning the solution space constructed based on the 0–1 RLE under the constraint of cumulative on-off duration is smaller than that based on 0–1 encoding.

Objective function

The objective functions, given in Eqs. (6) and (7), minimize grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production and maximize the renewable energy share rate, while ensuring the energy consumption requirements of oil well production.

where, \(\:{c}_{elec}\) denotes the grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production, which is calculated as the ratio of the total grid electricity consumed \(\:{E}_{grid}^{T}\) to the fluid production \(\:{Q}^{T}\) over the planning horizon, \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}/{\text{m}}^{3}\). \(\:{\alpha\:}_{green}\) represents the renewable energy share rate, and the proportion of PV electricity consumed \(\:{E}_{green}^{T}\) relative to the total electricity consumption \(\:{E}^{T}\) of the well. \(\:{Q}^{T}\) is the total oil production during the period, as expressed in Eq. (8) \(\:{\text{m}}^{3}\). \(\:{E}^{T}\) is the total electricity consumed, given in Eq. (9), the sum of consumed grid electricity \(\:{E}_{grid}^{T}\) and consumed green electricity \(\:{E}_{green}^{T}\), \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}\). \(\:{E}_{grid}^{T}\) is the cumulative grid electricity consumption, \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}\). \(\:{E}_{green}^{T}\) is the cumulative PV power consumption, \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}\).

where, \(\:{Q}^{t}\) denotes the cumulative oil production of the well in the t-th time period, \(\:{m}^{3}\).

where, \(\:{E}^{t}\) denotes the cumulative electricity consumption of the oil well in the t-th time period, \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}\).

Constraints

The single-well dynamic evolution model is constructed by sequentially connecting a series of well dynamic simulation submodels for the basic scheduling unit, as presented in Eq. (10), and dividing the planning horizon into multiple discrete time steps based on the basic scheduling unit. The output of the former simulation at a basic scheduling unit serves as the input for the subsequent time step, enabling an accumulative and iterative evolution process (see Fig. 6).

where, \(\:{h}_{1}^{t}\) denotes the initial submergence depth of the oil well at the t-th time period, m. \(\:{h}_{2}^{t}\) represents the final submergence depth at the t-th time period, m. \(\:f\) is the dynamic simulation model of the oil well for the basic scheduling unit, which calculates the cumulative oil production \(\:{Q}^{t}\), final submergence depth \(\:{h}_{2}^{t}\), instantaneous power \(\:{P}^{t}\), and cumulative electricity consumption \(\:{E}^{t}\) during that period, based on the initial submergence depth \(\:{h}_{1}^{t}\), simulation duration \(\:{\Delta\:}\text{t}\), and stroke frequency \(\:{N}^{t}\).

Daily production constraint

To ensure the long-term and stable exploitation of oilfield resources, the oil production of each well is subject to explicitly defined upper and lower bounds within a given time frame. The single-well daily production constraint is formulated in Eq. (11).

Here, \(\:{Q}_{1}^{T}\) denotes the lower bound of oil production for the well during planning horizon \(\:T\), \(\:{m}^{3}\), and \(\:{Q}_{2}^{T}\) represents the upper bound of oil production during the same period, \(\:{m}^{3}\).

Submergence constraint

The management system stipulates that the pump submergence must meet the minimum threshold constraint, as given in Eq. (12).

where, \(\:{h}^{t}\) denotes the real-time submergence depth of the oil well at the t-th time period, m, and \(\:{h}_{min}\) represents the minimum allowable submergence depth of the oil well, m.

On-off duration constraint

The on-off duration constraints for a well include: the minimum operating duration constraint, the minimum stoppage duration constraint, and the total operating duration constraint over the planning horizon. The minimum operating duration and stoppage duration constraints for each cycle are defined in Sect. 2.1 and are thus omitted here.

The total operation duration constraint requires that the cumulative operating duration of each well during the planning horizon falls within a reasonable range, as expressed in Eq. (13).

where, \(\:{O}_{2}\) and \(\:{O}_{1}\) represent the upper and lower bounds of the cumulative operating duration of the oil well during the planning horizon \(\:\text{T}\), respectively, min.

Improved NSGA-II

Genetic algorithm (GA) is capable of robust global search, high flexibility, and strong robustness, and not reliant on the derivative of the objective function. It has demonstrated significant advantages in multimodal, nonlinear, discrete, and high-dimensional optimization problems, and has subsequently become a prominent method for complex optimization challenges24.

The search process of the genetic algorithm is analogous to the optimization of the intermittent pumping well schedule. In the crossover operation, the operation schedule is encoded as chromosomes. The advantageous genes are preserved based on business logic, ensuring their retention in offspring through inheritance. In the mutation operation, targeted perturbations are applied to the current working schedule. The Gaussian mutation extends high-fitness gene segments, while the arithmetic crossover aggregates inefficient genes, thereby achieving a balance between local search and global exploration. For selection mechanisms, both genetic algorithms and intermittent pumping well schedule optimization adopt an elite retention strategy based on fitness evaluation, thereby achieving progressive optimization through iterative feedback loops. Notably, both mechanisms strictly adhere to the convergence criteria. This similarity suggests that by drawing on the crossover, mutation, and selection mechanisms of genetic algorithms—through schedule recombination and local innovation, supplemented by objective function evaluation and screening—systematic optimization of the operation schedule can be achieved, enhancing the efficiency and quality of schedule formulation.

As a classic algorithm in the field of multiobjective optimization, NSGA-II has achieved widespread success in engineering applications25. However, the conventional NSGA-II deploys generalized initialization, crossover, and mutation mechanisms, thereby neglecting to fully account for the distinctive characteristics and intricacy of intermittent pumping well operation schedules. This phenomenon leads to a decline in the rate of convergence and an increase in the difficulty of attaining near-optimal operation schedules within constrained timeframes.

To address this issue, this study deeply incorporates the operational characteristics of intermittent pumping wells and the source-load matching requirements into the algorithm design. By employing a customized initialization strategy, as well as improved crossover and mutation operators, the NSGA-II algorithm is systematically optimized (see Fig. 7), enhancing its solution efficiency and applicability in intermittent pumping schedule optimization.

Improved initialization strategy

The population initialization strategy constitutes the fundamental principle upon which the genetic algorithm is based. The initialization solution set, which simultaneously exhibits diversity, feasibility, and representativeness, establishes an efficient search foundation for subsequent evolution. The extant research suggests that knowledge-guided initialization has the potential to increase the convergence speed by 20–40%26.

This study integrates domain knowledge (original on-off strategy) and dynamic response factors (such as PV energy fluctuations) by employing a hybrid initialization strategy: (1) Benchmark group (20% of the population): generated by encoding the original schedule to establish a baseline; (2) Renewable-adaptive group (80%): constructed according to PV energy fluctuation patterns to reflect environmental adaptability.

Initialization base on the original operation schedule

The discrete scheduling method is designed based on the optimization parameter definitions (see Sect. 2.1). The fundamental scheduling unit is used to divide the whole operational duration into multiple discrete time segments. The state of each segment is defined as 0 (stopped) or 1 (running). To prevent pump-off events during intermittent pumping well operations, when a fundamental scheduling unit contains mixed states (e.g., running in the first part and stopped in the latter part), the unit’s state is designated as 0 (stopped). Considering a single day with a 10-minute fundamental unit, it discretizes a 144-element binary state array (0–1). The lengths of the corresponding runs (either 0-runs or 1-runs) are calculated for 0–1 run-length encoding. Subsequently, the initial solution is constructed following the definition of the solution space. To illustrate this, the working schedule of an oil well is a cycle of 3.08 h of operation and 3.13 h of shutdown, with a minimum duration of one hour for both shutdown and operation. The corresponding transformation process of the initial solution is shown in Fig. 8.

Initialization base on PV power fluctuation

The conventional random initialization yields solutions with limited compatibility with the fluctuation characteristics of PV power, as evidenced by experimental findings that exhibit an average correlation coefficient less than 0.3. It results in the sluggish convergence of optimization algorithms and the system’s renewable energy utilization rate. To address this issue, an intelligent initialization strategy is proposed that incorporates the fluctuation characteristics of PV power generation.

First, with the objective of maximizing the proportion of renewable power consumption during operation (Eq. 14), a PV power fluctuation-operation schedule matching model is established with the constraint of temporal alignment between green power and the on-off sequences of intermittent pumping wells. This method innovatively integrates the volatility characteristics of renewable energy into the initial solution generation process of the optimization algorithm, thereby laying a foundation for subsequent precise and rapid optimization.

where, \(\:{U}^{t}\) represents the state of the oil well during the designated time period \(\:t\), 0 means shutdown, 1 means operation. \(\:\eta\:\) is the proportion of renewable power consumption during the operation period.

Second, the Pearson correlation coefficient (see Eq. 15) is introduced as an evaluation metric for solution quality to screen candidate solutions with high compatibility with PV power fluctuations. Experimental results demonstrate that the optimized solution set achieves an average correlation coefficient obove 0.67.

Where, \(\:{\uprho\:}\) represents the correlation coefficient between the on-off schedule and the PV power fluctuation. \(\:{P}_{green}^{t}\) denotes the real-time power output of photovoltaic generation in a given period \(\:t\), kWh. \(\:\stackrel{-}{{P}_{green}}\) indicates the average power output of photovoltaic generation, kWh. \(\:\stackrel{-}{U}\) is the average state value.

Finally, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is implemented to maximize the objective function \(\:{\upeta\:}\) under specified threshold \(\:{\uprho\:}\) constraints, with the top 20% high-quality solutions retained to efficiently generate the initial solution set.

Improved crossover operator

The crossover operation of conventional genetic algorithms exhibits insufficient adaptability when applied to the optimization model in this study. First, the optimization parameters possess specific structural properties—including the initial state, the 0-run length, and the 1-run length—the standard crossover operators lack domain-specific guidance mechanisms, making it difficult to perform directed search on high-quality solutions and easily disrupting functionally significant gene structures. Second, the lack of a coordinated protection mechanism between state positions and run-length positions makes the algorithm prone to being trapped in local optima as iterations proceed, suppressing deep exploration of the solution space and resulting in a significant decrease in search efficiency. To address these challenges, two specialized crossover operators are designed: a crossover based on photovoltaic-matching key gene preservation and a crossover based on parents accumulation.

Crossover based on photovoltaic-matching key gene preservation

The maximum value distribution in the operational duration sequence of the solution must correspond to photovoltaic output patterns, and this extremum serves as the cut point for identifying and extracting key gene segments. Comparing the cut point values (1-run length (operational duration) peaks) between the two parents, the parent solution exhibiting the larger peak value is designated as Parent 1, while the other is assigned as Parent 2. The offspring’s leading sequence is to inherit the key gene segment from Parent 1, comprising the following elements: the initial state, the 0-run-length sequence, and the 1-run-length sequence before the cut point. The subsequent non-key gene is extracted from Parent 2’s post-cut gene fragment, thereby completing the directed crossover operation. If the cut points of the parent solution demonstrate positional discrepancies, then take the minimum values from the constraints of the 0-run-length and 1-run-length sequences are taken as completion (for comprehensive implementation details, refer to Fig. 9). The proposed operator generates new offspring that preserve key genes, which results in high photovoltaic matching, enables effective genetic transmission and significantly enhances the convergence speed.

Crossover based on parents cumulation

Optimizing the schedule of intermittent pumping wells involves optimizing multiple operation-shutdown durations. The value of each operation-shutdown duration is constrained within a corresponding range. This range is inversely proportional to the length of the basic scheduling unit. It is also positively correlated with the length of the planning cycle. As previously discussed, this results in an enormous solution space. If the operation-shutdown durations are scaled randomly, numerous infeasible solutions will be generated that violate engineering constraints, significantly impairing the search efficiency of the optimization algorithm. Therefore, an offspring generation mechanism based on parent-value accumulation is designed (Eq. 16), which uses stochastic weighting to increase the rate of feasible solutions produced. Parents with identical initial states are randomly paired. For each pair, new offspring are generated through the weighted accumulation of the 0-run length sequences (shutdown duration series) and the 1-run length sequences (operation duration series).

where, \(\:C\) represents the offspring solution, which inherits the initial state from Parent 1. \(\:{P}_{1}\) and \(\:{P}_{2}\) donate the run-length sequences of Parent 1 and Parent 2, respectively. \(\:{\upalpha\:}\) is a stochastic weighting coefficient controlling parental contribution. If the run-length sequence of the offspring \(\:\text{C}\) exceeds the permissible bounds, boundary correction is applied to rectify any invalid elements in the sequence.

Improved mutation

In GA, mutation is a critical mechanism for maintaining population diversity and directly determines the algorithm’s capacity to escape local optima. Conventional mutation (e.g., uniform or Gaussian mutation) has two notable limitations. It fails to adequately consider the feasible solution space of the intermittent well pumping schedule. The other is that the design for operational contexts involving renewable energy consumption is lacking. This study innovatively proposes two mutation mechanisms that incorporate the characteristics of renewable generation volatility, peak-oriented forward/backward fine-tuning mutation, and off-peak random neighborhood merge mutation. The mutation mechanisms efficiently explore the solution space through the synergistic interaction of peak-phase intensification and off-peak optimization.

Peak-oriented forward/backward fine-tuning mutation

Forward/backward fine-tuning is employed, centered on peaks within the 1-run length sequences (operating durations), to extend the peak regions via small-step adjustments. As illustrated in Fig. 10, this operator accumulates short periods before and after operating peaks with the peak itself, which effectively increases the intensity of energy consumption during periods of high renewable availability, thereby maximizing the utilization of green power. This directed mutation mechanism maintains operational continuity while significantly enhancing search efficiency.

Off-peak random neighborhood merge mutation

A small-step accumulation is implemented during the periods of grid power supply, as illustrated in Fig. 11. The number of valid solutions increases while ensuring production constraints by stochastically merging operation-shutdown segments before and after peaks, thereby reducing the frequency of operation-shutdown. It ensures that solutions are feasible while significantly reducing the risk of equipment degradation.

Results and discussion

Case arameters

To verify the feasibility of the model and the improved algorithm, an experimental scenario was constructed based on oil well production data from eastern China. The detailed parameters are listed in Table 2. The reservoir production performance was characterized via the Vogel IPR with key parameters including formation static pressure, flow pressure, and the corresponding formation fluid delivery capacity, shown in Fig. 12 (a) and (b). An oil well system is designed with 2.4 strokes per minute (SPM) and a maximum surface liquid discharge capacity of 14.64 \(\:{\text{m}}^{3}/\text{d}\), exceeding by 99.5% the formation’s maximum liquid delivery capacity of 7.34 \(\:{\text{m}}^{3}/\text{d}\). It is set with an intermittent schedule (3.08 h on, 3.13 h off), with the submergence depth ranging between 50 m and 150 m, resulting in a daily fluid production of 6.74 \(\:{\text{m}}^{3}/\text{d}\) with an energy consumption of 73.79 kWh/d (including 52.37 kWh from grid electricity and 21.42 kWh from PV electricity).

The real-time production process of the oil well system is illustrated in Fig. 12(c-f), with an initial submergence depth of 100 m and the system starting in an operating state. Owing to the formation liquid supply capacity being significantly lower than the system discharge capacity, the submergence depth continuously decreases during operation and gradually recovers during shutdown periods, as shown in Fig. 12(c-d). The system operates cyclically based on a fixed on/off schedule. Taking typical summer PV generation in eastern China as an example, a 24 kW PV unit is designed, with a maximum daily output of 73.78 kWh/day, as shown by the red curve in Fig. 12(e-f). The oil well power consumption is over on a stroke, as shown in Fig. 12(f). Under the original schedule, the green power absorption rate is 29.03%, and the grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production is 7.77 kWh/m³.

Comparison of optimization algorithms

Four sets of comparative experiments are conducted on the NSGA-II algorithm and its improvements, (1) the original NSGA-II, (2) an improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy (IGAWI), (3) an improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy and crossover operator (IGAWIC), and (4) an improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy, crossover operator, and mutation method (IGAWICM). The optimization code was developed in Python 3.9 and executed on a workstation equipped with a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-12700 F processor, 32 GB RAM, and Windows 10 operating system. Each experiment was independently replicated 30 times, and the mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation (CV), and median were calculated for the grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production, as listed in Table 3.

The series of enhancements to the NSGA-II exhibits substantial optimization effects on performance metrics. As the enhancements are progressively applied from the original version to the addition of the initialization strategy, then the crossover operator, and finally the mutation method—the mean and median values show an overall decreasing trend. For instance, the mean decreases from 6.67 (original) to 4.89 (an improvement of 26.69% in solution accuracy), while the median decreases from 6.75 to 4.91. It suggests that the algorithm successfully evades suboptimal local minima and converges toward superior solutions.

Furthermore, a decline in both the standard deviation and the CV is observed. The standard deviation exhibited a substantial decrease of 69.56% from 0.69 to 0.21. Concurrently, the CV decreased by 58.15%. The enhanced algorithm demonstrates diminished dispersion and a significant enhancement in stability.

The findings indicate that the incremental integration of improvements, namely the initialization strategy, the crossover operator, and the mutation method, consistently enhanced the output consistency and convergence of the NSGA-II. The IGAWICM delivered more stable and efficient results, effectively boosting the algorithm’s overall performance.

The distribution characteristics of the solutions and fitness values during the iterations were analyzed, taking the solution process of representative cases from each experimental group as an example, as depicted in Fig. 13.

Figure 14(a) shows the variation in the proportion of infeasible solutions. The infeasible solution ratio is the proportion of invalid solutions generated by the algorithm during iterations. It reflects the algorithm’s ability to produce feasible solutions. When the traditional NSGA-II is used as the baseline, the ratio of infeasible solutions exceeds 80% in the first 10 iterations, indicating low efficiency in generating feasible solutions during the early stage. Although this ratio then decreases sharply, significant fluctuations persist, revealing insufficient algorithmic stability. To IGAWICM, the ratio of infeasible solutions in the early stages decreases significantly, effectively suppressing infeasible solutions. It shows that enhanced initialization and other operations accelerate the generation of feasible solutions and improve the convergence speed of the algorithm.

Figure 14(b) shows the Hamming distances of the optimization parameters. The solution based on 0–1 RLE was transformed to 0–1 encoding. Then the pairwise Hamming distances between solutions at each iteration were computed and averaged. The Hamming distance indicates the solution diversity and convergence trends. Larger distances indicate dispersed solutions, whereas smaller distances signify convergence towards optima. In the baseline NSGA-II, the Hamming distance of solutions fluctuates violently during optimization, peaking at the 12th iteration before declining sharply. It indicates unstable solution diversity. By contrast, theIGAWICM (purple curve) gradually decreases the in Hamming distance before stabilizing, indicating that the improved algorithm effectively avoids premature convergence while maintaining diversity. It confirmed the superior convergence efficiency and refined solution clustering capability of the enhanced algorithm.

Figure 14(c) presents the distribution of grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production. The traditional NSGA-II (blue curve) shows high grid electricity consumption during the initial iterations, which remains elevated compared with the improved ones even after a reduction. By contrast, the IGAWI, IGAWIC and IGAWICM rapidly reduces grid electricity consumption, stabilizing at significantly lower levels, with the IGAWICM demonstrating the best performance. The improved NSGA-II achieves a better balance between fluid production demand, PV energy utilization, and grid electricity consumption, thereby improving the system’s overall economic performance.

Figure 14(d) displays the distribution of green power absorption rate. The traditional NSGA-II achieves a suboptimal green power absorption rate, whereas the improved methods demonstrate an increase in absorption rates with each iteration. The IGAWICM proves to be the most effective enhancement, delivering superior efficiency and stability in terms of green power absorption.

The IGAWICM significantly outperforms the traditional NSGA-II algorithm in several key areas: reducing the proportion of infeasible solutions, avoiding premature convergence, accelerating algorithm convergence, decreasing grid power consumption, and improving green power absorption rates. These results validated the effectiveness of the improvements for the green power absorption and power consumption optimization scenario, providing a practical and feasible approach to optimizing algorithms in related fields, such as integrating renewable energy with oil well operational systems.

Results analysis

The enhanced NSGA-II algorithm, informed by domain expertise, is used to optimize the on/off schedules of intermittent pumping wells. The parameters of the algorithm are enumerated in Table 4. The search efficiency of the algorithm is enhanced by an initialization strategy, crossover operator, and mutation method, given the intermittent operating characteristics of oil wells and the fluctuation characteristics of PV power. High-quality solutions can be obtained with 30 individuals and 30 generations, with the computation time kept below 10 min. Compared with extant studies (population size of 2000 and 500 generations)19, by improving the definition of optimization parameters through run-length encoding and incorporating green power fluctuation characteristics to guide the genetic algorithm’s search process, the population size is reduced by approximately 67 times and the iterations by 17 times. This results in an over 1000-fold improvement in computational efficiency while maintaining convergence accuracy. The finding indicates that the enhanced algorithm has a substantial advantage in terms of its capacity to expedite the resolution process.

The fitness values of individuals across iterations are shown in Fig. 15. The proposed initialization strategy enables the algorithm to identify a near-optimal operating scheme in the first iteration, reducing the grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production from 7.7 kWh/m³ (under the original scheme) to 7.5 kWh/m³. As the number of iterations progress, the enhanced crossover and mutation operators preserve key gene segments while enabling fine-tuning and recombination. It results in a continuous decline in grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production and a steady increase in green power utilization. Consequently, the algorithm rapidly converges to high-quality solutions.

Since this study addresses a multi-objective optimization problem, the solution process yields multiple Pareto-optimal solutions, from which the selection criteria can be customized according to practical requirements. In this paper, the solution with the minimum electricity consumption per unit liquid production is preferentially chosen under the constraint of achieving the lowest power curtailment rate. Figure 5(a) presents the optimal results of this case study, whereas Fig. 5(b) illustrates the process of converting the optimized parameters into operational regimes (previously detailed, omitted here). The dynamic parameters, including the flow pressure, submergence depth, and power consumption, are exhibited under the new operational schema, as illustrated in Fig. 13. After optimization, the intermittent pumping regime is no longer constrained to a conventional fixed-cycle pattern (see Fig. 13c-d), nor is the submergence depth variation confined to a fixed range (Fig. 13a-b). Instead, by enabling dynamic adjustment of load distribution through variable-cycle intermittent pumping within a reasonable submergence depth, the system better adapts to the fluctuations of PV power. The new schema consolidates non-operational periods by shifting them forward to non-green-electricity intervals and delays production phases to periods of abundant green power supply. The wellbore liquid storage ensures that there is an adequate supply of fluid during periods of high green power. Consequently, the well transitions from its initial operating state to an 8.5-hour shutdown. When the submergence depth is 327.57 m, the pumping system commences continuous operation for 7.7 h, from 8:30 a.m. to 4:15 p.m. The submergence depth diminishes to 51.18 m, which approaches but remains above the minimum limit of 50 m, and the system undergoes a shutdown process to avert pump-off. In periods of transition in proximity to green-power intervals, intermittent pumping employs minimal cycle durations (1-hour operation/1-hour shutdown) to maximize green power consumption. During periods of non-green electricity, the system is set to minimize the frequency of on-off operations, with a shutdown duration of 3 h and an operation duration of 2.8 h, allowing the wellbore to accumulate sufficient liquid while maintaining the minimum production.

A comparative analysis of the renewable energy share rate, the grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production, the actual grid electricity consumption, and the total green power utilization between the original and optimized operational schedule is presented in Table 5. Operating with the optimized schedule results in an approximate 101% increase in green power absorption, alongside a decrease of approximately 41% in grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production and actual grid electricity consumption. Furthermore, the fluid production increases by 0.29%. The optimized schedule saves 21.73 kWh of grid electricity per operating day, resulting in an annual reduction of nearly 8,000 kWh. Assuming a grid electricity price of 0.5 CNY/kWh, the annual cost savings would be approximately 4,000 CNY. There are no pump-off events while maintaining stable production under the new schedule. The synchronization of operation duration with green power volatility has been demonstrated to enhance renewable energy absorption, reduce grid electricity consumption, and improve economic efficiency.

The method proposed in this study can be extended to oilfields that combine PV generation with intermittent production modes due to insufficient formation fluid supply. By automatically adjusting the operating schedule of intermittent wells in real time according to the fluctuation characteristics of green power, this approach not only enhances the local consumption of green electricity during oil and gas production and alleviates the operational stress on regional grids caused by high penetration of variable renewable energy, but also significantly reduces oilfield dependence on grid electricity, leading to substantial cost savings. This strategy provides a practical technical pathway for oilfield operators to promote green power substitution and optimize energy consumption structures, contributing to both improved economic performance and low-carbon development.

From a broader perspective, the integration of variable power supply with interruptible load scheduling propo1ed in this study helps mitigate challenges faced by grid operators when integrating green power. It also offers guidance for policymakers in designing localized incentives for industrial green power applications, and provides a reference for energy developers and other stakeholders to explore the synergy between renewable energy generation and flexible electricity demand in different regions. This approach is adaptable to various scenarios - for example, by adjusting the parameters of power fluctuation, it can be applied in regions with high wind power penetration, and it can also be extended to flexible industrial loads beyond oil extraction - thus demonstrating broad practical applicability.

Conclusion

In response to the challenge of optimizing intermittent pumping well schedules under the variability of green electricity in source-load matching scenarios, this study designs a multi-objective optimization model with the objectives of maximizing the green electricity share and minimize grid electricity consumption per unit of liquid production. A 0–1 run-length encoding method was proposed for defining optimization parameters, which, compared with the conventional 0–1 state encoding, effectively reduced the solution space size and decreased the probability of generating infeasible solutions, providing a novel parameter modeling approach for intermittent oil production scheduling.

Building on this, a self-evolving optimization method for intermittent pumping schedules guided by photovoltaic power fluctuations was designed and integrated with the NSGA-II algorithm, with targeted improvements to key operators including initialization, crossover, and mutation. By introducing an initialization strategy that fuses the original schedule with PV energy fluctuation characteristics, the proportion of infeasible solutions decreased from 93.33% to 56.67%, a reduction of 39% points. The design of a key-gene-preserving crossover method based on green power matching and an accumulative crossover operator based on parent values further reduced the infeasible solution ratio to 36.67%, significantly enhancing the preservation of high-quality genes and search efficiency. Meanwhile, peak-guided forward/backward fine-tuning mutations and random-neighbor merging mutations in non-peak periods were implemented to escape local optima and improve solution quality and diversity.

For ultra-large-scale solution spaces (\(\:{2}^{144}\)), the proposed method required only 30 populations and 30 generations, less than 10 min to obtain high-quality solutions that meet engineering requirements, achieving over a thousandfold improvement in computational efficiency. Using typical oil well data as an example, grid electricity consumption per unit liquid production decreased from 7.77 \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}/{\text{m}}^{3}\) to 4.53 \(\:\text{k}\text{W}\text{h}/{\text{m}}^{3}\), and the share of renewable energy increased by more than twofold, significantly enhancing green power self-consumption and demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the proposed method.

In summary, this paper presents an optimization approach that leverages the characteristics of renewable power fluctuations to guide the targeted improvement of key genetic algorithm operators. The method achieves self-evolving optimization of intermittent pumping schedules under a fitness supervision mechanism, providing a novel solution paradigm for source-load coordinated scheduling in renewable energy scenarios. Future research may further explore adaptive integration mechanisms between engineering constraints and genetic operators, investigate patterns of formation fluid supply and well power characteristics, and facilitate efficient application of this approach in complex scenarios, such as wind-solar complementarity and multi-well schedule optimization.

Data availability

Data cannot be made publicly available; reader should contact the corresponding author for details.

Abbreviations

- \({\text{C}}\) :

-

The offspring solution

- \({\text{c}}_{\text{elec}}\) :

-

The grid electricity consumption per unit fluid production (\(\text{kWh/}{\text{m}}^{3}\))

- \({\text{E}}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The total electricity consumption (\({\text{kWh}}\))

- \({\text{E}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The cumulative electricity consumption of the oil well in the t-th time period (\({\text{kWh}}\))

- \({\text{E}}_{\text{green}}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The total consumed photovoltaic electricity (\({\text{kWh}}\))

- \({\text{E}}_{\text{grid}}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The total consumed grid electricity (\({\text{kWh}}\))

- \({\text{F}}\) :

-

The dynamic simulation model of the oil well for the basic scheduling unit

- \({\text{h}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The real-time submergence depth of the oil well at the t-th time period (m)

- \({\text{h}}_{1}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The initial submergence depth of the oil well at the t-th time period (m)

- \({\text{h}}_{2}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The final submergence depth at the t-th time period (m)

- \({\text{h}}_{\text{min}}\) :

-

Tthe minimum allowable submergence depth of the oil well (m)

- \({\text{N}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The stroke frequency (\({\text{min}}^{-1}\))

- \({\text{n}}_{\text{s}}\) :

-

The maximum index of 0-run

- \({\text{n}}_{\text{t}}\) :

-

The number of intervals

- \({\text{O}}_{1}\) :

-

The lower bounds of the cumulative operating duration of the oil well during the planning horizon (min)

- \({\text{O}}_{2}\) :

-

The upper bounds of the cumulative operating duration of the oil well during the planning horizon (min)

- \({\text{P}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The instantaneous power (kWh)

- \({\text{P}}_{\text{green}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The real-time power output of photovoltaic generation in a given period \({\text{t}}\) (kWh)

- \(\overline{{\text{P} }_{\text{green}}}\) :

-

The average power output of photovoltaic generation (kWh)

- \({\text{P}}_{1}\) :

-

The run-length sequences of Parent 1

- \({\text{P}}_{2}\) :

-

The run-length sequences of Parent 2

- \({\text{Q}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The cumulative oil production of the well in the t-th time period (\({\text{m}}^{3}\))

- \({\text{Q}}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The fluid production (\({\text{m}}^{3}\))

- \({\text{Q}}_{1}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The lower bound of oil production for the well during planning horizon (\({\text{m}}^{3}\))

- \({\text{Q}}_{2}^{\text{T}}\) :

-

The upper bound of oil production during the same period (\({\text{m}}^{3}\))

- \({\text{S}}_{0}\) :

-

The initial state

- \({\text{T}}\) :

-

The planning horizon (min)

- \({\text{T}}_{\text{1,c}}\) :

-

The lower bound of a single well stoppage duration (min)

- \({\text{T}}_{\text{1,o}}\) :

-

The lower bound of a single well operating duration (min)

- \({\text{tc}}^{\text{i}}\) :

-

The length of the i-th 0-run

- \({\text{to}}^{\text{i}}\) :

-

The length of the i-th 1-run (min)

- \(\Delta t\) :

-

The basic scheduling unit (min)

- \(\stackrel{\text{-}}{\text{U}}\) :

-

The average state value

- \({\text{U}}^{\text{t}}\) :

-

The state of the oil well during the designated time period \({\text{t}}\)

- \(Z\) :

-

The set of integers

- \(\alpha\) :

-

The stochastic weighting coefficient controlling parental contribution

- \(\alpha _{{green}}\) :

-

The renewable energy share rate

- \(\rho\) :

-

The correlation coefficient between the on–off schedule and the green power fluctuation

- \(\eta\) :

-

The proportion of renewable power consumption during the operation period

- CV:

-

The coefficient of variation

- IGAWI:

-

Improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy

- IGAWIC:

-

Improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy and crossover operator

- IGAWICM:

-

Improved NSGA-II with initialization strategy, crossover operator, and mutation method

- NSGA-II:

-

Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- RLE:

-

Run-length encoding

- RL:

-

Run-length

- 0–1 RLE:

-

0–1 Run-length encoding

References

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook-2024 (China Statistics, 2024).

Clancy, S. A., Worrall, F., Davies, R. J. & Gluyas, J. G. An assessment of the footprint and carrying capacity of oil and gas well sites: the implications for limiting hydrocarbon reserves. Sci. Total Environ. 614, 586–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.160 (2018).

Zhang, Q. Sustainable and clean oilfield development: how access to wind power can make offshore platforms more sustainable with production stability. J. Clean. Prod. 294, 126225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126225 (2021).

Li, P., Lian, J., Ma, C. & Zhang, J. Complementarity and development potential assessment of offshore wind and solar resources in China seas. Energy Convers. Manag. 296, 117705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117705 (2023).

Shangi, L. et al. Pathways for supply security and carbon-neutral transition in the oil products industry: A comprehensive technology portfolio evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 499, 145241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.145241 (2025).

Wu, M., Kang, Y., Fan, X., Li, C. & Lan, M. Study and practice of green transition by China’s oil and gas enterprises under carbon peak and carbon neutrality background. Petroleum Sci. Technol. Forum 41, 18–24 https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1002-302x.2022.04.003 (2022).

Nourollahi, R., Akbari-Dibavar, A., Agabalaye-Rahvar, M., Zare, K. & Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Hybrid robust-CVaR optimization of hybrid AC-DC microgrid. In 11th Smart Grid Conference (SGC) 1–5 (IEEE, 2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/SGC54087.2021.9664021

Nourollahi, R., Gholizadeh-Roshanagh, R., Feizi-Aghakandi, H., Zare, K. & Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. Power distribution expansion planning in the presence of wholesale multimarkets. IEEE Syst. J. 17, 1684–1693. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2022.319209 (2023).

Jodeiri-Seyedian, S. S. & Veysi, M. Microgrid-level reliability assessment of mid-term electricity provision under intermittency of renewable distributed generation: a probabilistic conditional value at risk modeling. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 261, 111087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2025.111087 (2025).

Nourollahi, R., Nojavan, S. & Zare, K. Risk-based purchasing energy for electricity consumers by retailer using information gap decision theory considering demand response exchange. In Electricity Markets: New Players and Pricing Uncertainties 135–168 (Springer International Publishing, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36979-8_7.

Zhang, Q., Gao, Z. H., Chen, S. Y. & Liu, B. Y. Review on the challenges and strategies in oil and gas industry’s transition towards carbon neutrality in China. Pet. Sci. 20, 3931–3944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petsci.2023.06.004 (2023).

Xiao, Y. et al. Dynamic optimization of carbon reduction pathways in coastal metropolises considering hidden influence of decarbonization on energy demand. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 58, 600–609 (2024).

Lei, Q. et al. Achievements and future work of oil and gas production engineering of CNPC. Pet. Explor. Dev. 46, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1876-3804(19)30014-X (2019).

Li, K., Xu, W., Han, Y., Ge, F. & Wang, Y. A hybrid modeling method for interval time prediction of the intermittent pumping well based on IBSO-KELM. J. Int. Meas. Confederation. 151, 107214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2019.107214 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. OTC,. Edge optimization analytics and control: an integrated device of intelligent intermittent pumping for tight oil wells. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Asia (2022). https://doi.org/10.4043/31669-MS

Ma, G. et al. IPTC,. Research on intelligent optimization of intermittent lift systems for low production oil wells. International Petroleum Technology Conference (2024). https://doi.org/10.2523/IPTC-24130-MS

Jiang, M. et al. Optimization of intermittent oil recovery system based on improved NSGA-II algorithm. China Pet. Mach. 52, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.16082/j.cnki.issn.1001-4578.2024.03.001 (2024).

Pu, J. Research on the optimization technology of interval pumping for pumping well. Energy Conserv. Meas. Pet. Petrochem. Ind. 15, 51–56. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2097-3322.2025.04.010 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Multi-Objective Schedule Optimization for Intermittent Pumping Wells Based on NSGA-II. Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference. SPE. (2023). https://doi.org/10.2118/216871-MS

Wang, J. et al. Optimization of staggered peak intermittent pumping operation scheduling of pumping unit well clusters under wind, solar and energy storage microgrid with improved adaptive GAPSO hybrid algorithm. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 252, 213897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2025.213897 (2025).

National Energy Administration. Grid Operation Guidelines GB/T 31464 – 2015 032002 (Standards Press of China, 2015).

Li, J., Chen, Z., Ni, C. & Lei, P. Run length encoding based weld seam detection from point clouds of ship stiffened panel. J. Ocean. Eng. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joes.2024.07.002 (2024).

Tan, C. et al. Scheduling optimization of staggered peak intermittent pumping of pumping well group in cluster well site. J. Xi’an Shiyou University(Natural Sci. 36, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-064X.2021.05.011 (2021).

Ali, M. Z., Awad, N. H., Suganthan, P. N., Shatnawi, A. M. & Reynolds, R. G. An improved class of real-coded genetic algorithms for numerical optimization. Neurocomputing 275, 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2017.05.054 (2018).

Ghiasi, H., Pasini, D. & Lessard, L. A non-dominated sorting hybrid algorithm for multi-objective optimization of engineering problems. Eng. Optim. 43, 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03052151003739598 (2011).

Radhakrishnan, N. & Kandeepan, S. An improved initialization method for fast learning in long short-term memory-based Markovian spectrum prediction. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 7, 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCCN.2020.3046330 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge He Liu for his general technical support and provision of laboratory space during the initial phase of this research.

Funding

This work was supported by National Major Science and Technology Project for Oil & Gas (2024ZD14065) and China National Petroleum Corporation (2023ZZ09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.R. and D.J. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. M.Q. and Y.L. performed the experiments. The manuscript was written by M.Q., and Y.L. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiao, M., Ren, F., Li, Y. et al. Optimal on-off scheduling for intermittent pumping wells under grid-connected pv systems. Sci Rep 15, 39050 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26081-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26081-2