Abstract

The water source area (WSA) of the central route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project (SNWD-C) is crucial for China’s water and ecological security. However, vegetation dynamics and associated driving mechanisms in this region remain understudied. This study integrates Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS)–derived Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data (2000–2022) with climatic and anthropogenic factors using the Google Earth Engine platform. To quantify vegetation dynamics, we employed Sen’s slope estimator, the Mann–Kendall test, and the coefficient of variation. Furthermore, the Optimal Partition Geographical Detector (OPGD) model was applied to identify the dominant drivers of vegetation change and to explore their interactive effects. Results show that 98.8% of the WSA (excluding water bodies) maintained a high average NDVI (> 0.5), with significant greening trends (+ 0.0038/a) in 81.4% of the area, mainly in mid-low altitude grasslands. Urban areas showed localized vegetation decline (1.8%). Land surface temperature (LST), Digital Elevation Model (DEM), human footprint (HFP), and land cover (LC) were major drivers. Interactions among these factors significantly improved explanatory power. Cooling trends promoted greening, while warming and intense human activities were linked to vegetation decline. This study provides insights into the mechanisms of vegetation change in the WSA and offers scientific guidance for ecological restoration and sustainable water resource management under the SNWD-C framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Vegetation plays a crucial role in global ecosystems as a core component of the carbon and water cycles, as well as energy exchange. It also serves as a sensitive indicator of human-induced changes, such as land use practices and climate change1,2. By regulating climate, conserving water, reducing soil erosion, and protecting biodiversity, vegetation significantly contributes to ecological integrity and sustainable development3,4,5. Since the 1980s, satellite remote sensing has enabled large-scale vegetation monitoring, revealing considerable greening across China due to national initiatives in water conservation and ecological restoration6,7. Understanding vegetation dynamics and their driving mechanisms in key ecological zones is critical for advancing ecosystem management and restoration strategies.

With the advancement of remote sensing technology, satellite-based vegetation monitoring has become indispensable in environmental research8. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), highly correlated with vegetation cover, is a widely used metric for assessing vegetation health and analyzing spatiotemporal changes9,10,11. MODIS NDVI data, featuring high temporal frequency, moderate spatial resolution, and broad coverage, are well-suited for long-term vegetation monitoring12,13. Meanwhile, Google Earth Engine (GEE) offers access to large geospatial datasets and robust cloud computing power, facilitating efficient analyses of land cover change, vegetation trends, and water resource management14,15.

Vegetation dynamics are influenced by a combination of climatic and anthropogenic factors, including temperature and precipitation variability, land use change, ecological engineering, grazing, and urbanization16,17,18. To quantify vegetation change, non-parametric methods such as the Theil–Sen slope estimator19 and Mann–Kendall trend test20 have been widely adopted for their robustness in long-term trend detection21,22,23. To investigate the driving mechanisms behind vegetation dynamics, traditional linear regression models and residual trend analysis have been widely applied in vegetation change studies. However, these methods often rely on assumptions of linearity and spatial homogeneity, which limit their applicability in ecologically complex regions characterized by spatial heterogeneity and nonlinear interactions17,24,25. To overcome these limitations, Wang et al.26 introduced the Geographical Detector model, which can effectively quantify spatial stratified heterogeneity without assuming linear relationships. Nevertheless, the model’s performance is influenced by the method of factor discretization. The commonly used Jenks Natural Breaks method is prone to subjectivity and may affect result reliability27. To address this issue, the Optimal Partition Geographical Detector (OPGD) model employs an optimized discretization strategy that maximizes spatial heterogeneity and minimizes human bias, thereby improving the robustness and accuracy of geographic analyses28. The OPGD model is particularly advantageous in detecting nonlinear effects and factor interactions, yet its application in vegetation change analysis remains limited29.

The central route of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project (SNWD-C) is a major infrastructure initiative designed to alleviate water shortages and optimize water allocation in North China30. Its water source area (WSA), located in a key ecological zone, plays a fundamental role in ensuring water supply and ecological balance. Vegetation conditions in the WSA directly influence water regulation, restoration success, and regional sustainability. However, the combined influence of climate variability and human activity on vegetation in the WSA is still not fully understood. Although several studies have examined vegetation trends in this region31,32,33, a comprehensive assessment integrating long-term multi-source data within a robust computational framework to quantify the individual and interactive effects of driving factors, particularly using advanced models like the OPGD that handle spatial heterogeneity well, is still lacking for the WSA.

To fill this gap, this study employs the GEE platform to process MODIS NDVI data and environmental datasets from 2000 to 2022. Vegetation trends are quantified using the Sen slope estimator, Mann–Kendall test, and coefficient of variation. The OPGD model is used for the first time to investigate the driving forces of vegetation dynamics in the WSA, which is applied to evaluate the independent and interactive impacts of natural and anthropogenic drivers. Visual interpretation is also used to qualitatively explore the influence of major drivers and ecological restoration efforts. This study aims to: (1) characterize the spatiotemporal patterns of vegetation dynamics in the WSA from 2000–2022; (2) quantify the relative importance of natural and anthropogenic driving factors; and (3) elucidate the interactive effects between these drivers using the OPGD model. The ultimate goal is to provide scientific guidance for ecological restoration and sustainable water resource management under the SNWD-C framework.

Study area and data sources

Study area

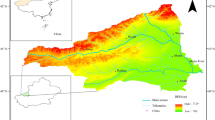

The WSA of the central route of the SNWD-C Project (31°20′–34°10′N, 106°00′–111°45′E) encompasses the hydrological catchment of the Danjiangkou Reservoir, the primary water source for the project. This area has been officially designated as a key water source protection zone in China based on integrated hydrological, ecological, and administrative criteria. Geographically, it extends across the southern slopes of the Qinling Mountains and the northern foothills of the Daba Mountains, forming a crucial ecological barrier and water resource safeguarding region.. The WSA encompasses the Hanzhong and Ankang Basins, including the Danjiangkou Reservoir and the upper reaches of the Hanjiang River Basin, forming a critical ecological barrier and water resource protection zone (Fig. 1). This area was specifically chosen for study due to its strategic role in water supply security for the SNWD-C project and its sensitivity to both natural and anthropogenic disturbances.

The WSA spans approximately 95,200 km2 and supported a population exceeding 16 million as of 2022. Population distribution is spatially uneven, with higher densities observed in the Hanzhong and Ankang Basins as well as in the eastern hilly and plain areas. The region experiences a multi-year mean temperature of approximately 14 °C and an average annual precipitation of around 900 mm, gradually decreasing from south to north34, with nearly 80% of the annual precipitation occurring between May and October. Land use in the WSA is primarily composed of forests, grasslands, and croplands, with dominant vegetation types being deciduous broadleaf–conifer mixed forests that exhibit distinct vertical zonation.

Given the official designation of the WSA and its strategic importance for the SNWD-C, understanding the current state and temporal evolution of vegetation in this area is crucial for ecological protection and sustainable water resource management.

Data sources

Vegetation growth and dynamics are jointly influenced by natural environmental conditions and anthropogenic activities2. Among these, topography, climate, and soil are the primary natural factors influencing vegetation growth, while human socioeconomic activities can either facilitate or constrain vegetation growth18. To identify the driving factors of vegetation distribution and change, we reviewed existing studies16,17,18 to select widely used and validated variables, and integrated these with the natural and anthropogenic conditions of the study area and data availability to construct a comprehensive set of influencing factors. The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was used to represent topography, while five climatic factors—land surface temperature, precipitation, net surface radiation, wind speed, and soil moisture—were included35. Anthropogenic drivers comprised land cover type36, surface water distribution37, and the global human modification index38. Land cover type is a key anthropogenic driver as its distribution and changes are predominantly the result of human land use decisions and activities (e.g., urbanization, agriculture, forestry). The NDVI time series and all auxiliary datasets, encompassing terrain, climate, soil, and socioeconomic indicators, were obtained from the GEE platform (Table 1).

This study applies the OPGD model (implemented in R) and related statistical analysis models (implemented in Python) to evaluate the contribution of potential driving factors to vegetation distribution and changes in the WSA. To ensure consistent data processing and retrieval, we performed monthly compositing on the GEE platform, standardized the projection coordinate system, and downloaded the processed data for further analysis.

To eliminate the impact of water body changes on the analysis of vegetation evolution, we applied a water body mask to the NDVI and auxiliary datasets. Since the implementation of the SNWD-C in December 2014, the maximum water area of the Danjiangkou Reservoir has remained relatively stable due to human regulation. Therefore, we used the combined extent of permanent and seasonal water bodies from 2020 as the water mask to exclude water bodies from the study area.

Methods

The methodology and technical process employed in this study are shown in Fig. 2, and are primarily composed of the following three steps: (1) Acquiring MODIS NDVI and related auxiliary datasets for the vegetation growing season (April to October) from 2000 to 2022; (2) Analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution trends of vegetation in the WSA; (3) Analyzing the driving factors behind vegetation and its evolution.

Data composition

An appropriate data composition strategy is crucial when analyzing vegetation changes and their driving factors39. On the GEE platform, monthly data composition was performed using methods such as the monthly maximum value composition (MVC), mean composition, and sum composition for the NDVI, LST, and PRE datasets. These methods generated the corresponding monthly datasets.

For annual data composition, we extracted the 75th percentile of the NDVI monthly data during the vegetation growing season for each year to generate the annual NDVI dataset. The primary reason for selecting the 75th percentile is that this approach effectively reduces the impact of extreme values, thereby minimizing biases caused by outliers. As a result, it more accurately reflects the typical growth conditions of vegetation. This method highlights NDVI values representative of most normal growth situations, enhancing the robustness and comprehensiveness of the ecological assessment and providing reliable data support for subsequent research and decision-making. For other monthly datasets, the annual composition was performed using the mean value of the vegetation growing season.

Trend analysis

Sen slope (also known as Theil-Sen Median) was used to calculate the variation trend of time series x19:

where i and j are the serial numbers of time series x, xi and xj are the time series values in ith and jth numbers, Median() is the median function. The positive slope indicates that x increases, whereas the negative slope means that x decreases. The absolute value of slope indicates the degree of variation in x.

In addition, Mann–Kendall (MK) test was used to evaluate the significance of the NDVI trends20.

Sequence fluctuation analysis

The coefficient of variation (CV), calculated by the standard deviation and mean of the time series, is a statistic to measure the degree of fluctuation of the time series x:

where std() and mean() are the standard deviation and mean value of x, respectively. Smaller CV indicates that x is more stable, whereas the bigger CV means that x is less stable. In this study, CV was used to estimate the relative fluctuation degree of the long-term NDVI and influencing factors.

Geographic detector model

Spatially Stratified Heterogeneity (SSH) refers to the phenomenon where the variations within a specific stratum are more similar to each other than to those between different strata. SSH represents the spatial manifestation of both natural phenomena and socio-economic processes. Examples of SSH include land use types, climate zones, and remote sensing classifications in spatial data.

The Geographical Detector model is a suite of statistical methods developed to identify spatial heterogeneity and uncover the driving forces behind observed phenomena40. Unlike traditional approaches, it does not rely on linear assumptions and features a straightforward formulation with clear physical interpretation. The core concept of the model is to partition the study area into multiple sub-regions. If the sum of the variances within these sub-regions is smaller than the variance of the entire region, this indicates the presence of spatial heterogeneity. Furthermore, if the spatial distributions of two variables show a tendency to align, this implies a statistical association between them. The q-statistic of the Geographical Detector model can be used to measure spatial heterogeneity, detect driving factors, and analyze the interactions between variables. By calculating the q-value, the influence and heterogeneity of the driving factor parameter X on the variable Y can be analyzed:

where N and \(\sigma^{2}\) represent the number of observations and the total variance of Y in the entire study area, respectively; Nj and \(\sigma_{j}^{2}\) represent the number of observations and the total variance of Y in the sub-regions of the explanatory variable X. SSW represents the sum of within-group variances, while SST is the total variance of the entire region. The q-statistic measures both linear and nonlinear relationships between X and Y. q ∈ [0,1] the larger the q-value, the greater the influence of the driving factor parameter X on the variable Y, and vice versa.

The optimization of parameters in geospatial data is a prerequisite for studying spatial heterogeneity28. The OPGD model is an R software package for spatial heterogeneity analysis and factor exploration27. It includes methods for optimal spatial data discretization analysis and the optimal parameter geographical detector model, and can output the computational process data and results of geographical detector analysis. Currently, OPGD model has been widely applied in fields such as geological disasters, ecosystems, diseases, and rural settlements28,29.

We use the OPGD model to analyze the optimal data discretization method, driving factor analysis, and interaction analysis of vegetation and its evolution in the WSA. Driving factor detection quantitatively evaluates the extent to which driving factors influence vegetation change, with larger q-values indicating stronger explanatory power of the driving factors on vegetation evolution. Interaction detection is used to assess whether the interaction between two driving factors enhances, weakens, or remains independent in its impact on vegetation evolution27.

Pearson correlation coefficient

The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) can accurately measure the degree of correlation between two time series variables (i.e. x and y). In this study, the relationship between vegetation indicator (NDVI in this study) and driving factors was estimated using PCC41:

where PCC > 0 indicates that the two variables are positively correlated, whereas PCC < 0 means that the two variables are negatively correlated. The absolute value of PCC indicates the degree of correlation between the two variables.

Results and analysis

Reclassification of land cover in the WSA

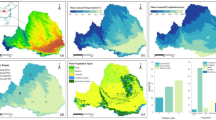

Vegetation and its evolution are closely related to land cover42. To better understand the vegetation evolution in the WSA, we reclassified the annual MODIS land cover data (MCD12Q1) from 2001 to 2022 based on the actual land cover conditions in the area. The original 17 land cover types were grouped into four categories: forest, grassland, water bodies, and others. Specifically, forest was derived from classes 1–5 in MCD12Q1, grassland was obtained by combining classes 6–10, water bodies were defined using the combined boundary mask of permanent and seasonal water bodies in the study area in 2020, and the remaining areas were classified as "Other LCs." The reclassified land cover for 2022 is shown in Fig. 3a, indicating that the majority of the WSA is covered by forests and grasslands. Figure 3b presents the land cover transitions from 2001 to 2011 and 2022, revealing two significant land cover transitions over the past two decades: grassland turning into forest (e.g., afforestation) and other land types converting into grassland (e.g., grain-to-green programs). Notably, the conversion intensity from 2001 to 2011 was much higher than that from 2011 to 2022.

Land cover analysis of the WSA based on reclassification results of MCD12Q1 from 2001, 2010, and 2022: (a) 2022 land cover distribution, (b) temporal changes of land cover from 2001 to 2022, (c) extracted areas of change and stability in land cover from 2001 to 2022, and (d) area proportions of different land cover regions.

Based on the reclassified land cover data for 2001, 2011, and 2022, we extracted regions of land cover change and stability in the study area using the following rules: pixels labeled as forest in all three years (2001, 2011, and 2022) were defined as “Stable forest”, and pixels labeled as grassland in all three years were defined as “Stable grassland”. All remaining pixels, excluding “Water bodies”, were classified as “Others”. Stable forest and Stable grassland represent regions with unchanged land cover between 2001 and 2022, while Others represent regions where land cover changed over the same period, including areas heavily influenced by human activities such as farmland and urban settlements (Fig. 3c). Figure 3d shows that, from 2001 to 2022, the areas of Stable forest, Stable grassland, Water bodies, and Others in the WSA accounted for 36.3%, 30.7%, 1.7%, and 31.3%, respectively.

Spatiotemporal patterns of NDVI in the WSA

The WSA is characterized by high vegetation coverage. Considering this regional characteristics, both annual and multi-year average NDVI values were classified into six standard levels: [0, 0.5], (0.5, 0.6], (0.6, 0.7], (0.7, 0.8], (0.8, 0.9], and (0.9, 1] (Figs. 4 and 5a). Figure 4 shows that the annual NDVI distribution in the WSA for 2001, 2011, and 2022 exhibits clear spatial heterogeneity and significant greening trends. From 2000 to 2022, the greening mechanism in the WSA is characterized by a reduction in the proportion of medium–low vegetation cover (0.5 < NDVI < 0.8) and a significant increase in the proportion of high vegetation cover (NDVI ≥ 0.8).

Figure 5a shows the multi-year average NDVI spatial distribution for the WSA from 2000 to 2022 and the corresponding area statistics. The proportions of the six NDVI levels are 1.2%, 1.8%, 8.0%, 26.4%, 62.3%, and 0.4%, respectively. After excluding water bodies, over 98.8% of the WSA has an average NDVI greater than 0.5. The northern Qinling Mountains and the southern Daba Mountains exhibit very high NDVI values, while the Hanzhong Basin, Ankang Basin, major towns, roads, and the area around the Danjiangkou Reservoir have lower NDVI values. Visually, the vegetation cover in the WSA is strongly correlated with land cover types and the DEM.

A trend analysis was conducted to calculate the NDVI change rate (NDVI.rate) for each pixel in the WSA from 2000 to 2022, with the spatial distribution shown in Fig. 5b. The NDVI.rate during the growing season of vegetation in the WSA ranges from -0.032 to 0.019 per year, indicating an overall increasing trend. From 2000 to 2022, 1.8% of the area experienced a degradation trend (NDVI.rate ≤ -0.002 per year), primarily in urban areas with high human activity. Approximately 16.8% of the area exhibited no significant change in vegetation (-0.002 < NDVI.rate < 0.002 per year), corresponding to high-altitude forest regions in the Qinling and Daba Mountains. Around 81.4% of the area showed a significant greening trend (NDVI.rate ≥ 0.002 per year), predominantly in mid-low altitude stable grassland and others regions.

The coefficient of variation of NDVI (NDVI.CV) serves as an indicator of the relative intensity of vegetation growth fluctuations over time. A higher NDVI.CV value signifies greater variability in vegetation cover, indicating a more fragile ecosystem, while a lower NDVI.CV value suggests minimal vegetation change and greater ecosystem stability and resilience21. Figure 5 shows that the spatial distribution of the NDVI.CV from 2000 to 2022 in the WSA is closely correlated with the long-term average NDVI (NDVI.mean) and NDVI.rate. Specifically, areas with higher vegetation cover exhibit more stable vegetation and less fluctuation in growth, whereas regions with medium-to-low vegetation cover show more pronounced changes and greater fluctuations.

The average NDVI.CV in the WSA is 0.054, which is relatively low compared to other study areas17,21,43, suggesting a more stable trend in vegetation evolution. Areas with low to moderate CV (NDVI.CV < 0.06) account for approximately 44.6% of the region, predominantly found in Stable forest region, where vegetation growth is robust, cover is high, and natural conditions are stable. In contrast, areas with greater fluctuations in NDVI (NDVI.CV ≥ 0.06) represent 55.4% of the area. The spatial distribution of these areas largely overlaps with regions exhibiting higher NDVI.rate, suggesting that, in the WSA, a higher vegetation change rate corresponds with stronger fluctuations.

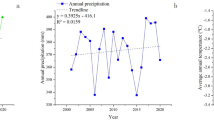

Figure 6a illustrates the annual NDVI trend in the WSA from 2000 to 2022, showing a stable and significant increase with an overall change rate of + 0.0038 per year. The vegetation evolution process is characterized by a steady decline in the proportion of low NDVI (NDVI ≤ 0.5) and medium NDVI (0.5 < NDVI ≤ 0.8) areas, while the proportion of high NDVI (NDVI > 0.8) areas has significantly increased.

Statistical analysis reveals that NDVI.rates vary among different land cover types. The average NDVI.rates for the Stable forest, Stable grassland, and Others categories are 0.0026, 0.0049, and 0.0044 per year, respectively. This indicates that the significant greening phenomenon in the WSA from 2000 to 2022 mainly occurred in the Stable grassland and Others regions.

Analysis of driving factors of NDVI based on the OPGD model

Optimal discretization results

As the Geographical Detector model requires the input driving factors to be categorical or classified data, continuous variables must first be discretized to enable the analysis27,28. The OPGD model automatically performs optimal spatial data discretization, which divides continuous variables into discrete intervals that maximize internal homogeneity while enhancing inter-region variability, thereby preserving the spatial characteristics of the data.

Following previous studies on discretizing driver factors22,27,29, the explanatory variables were classified into 6 to 8 categories. Five discretization methods were employed: Natural Breaks, Standard Deviation Breaks, Geometric Breaks, Quantile Breaks, and Equal Breaks. The OPGD model automatically evaluates these five methods for each variable and selects the one that maximizes the q-value of the factor detector result, indicating the strongest explanatory power for the response variable The optimal method and parameters for each variable are listed in Table 2. For the geographical detector analysis of NDVI.mean, the optimal discretization parameters for DEM, SW.mean, and HFP.2020 were Natural Breaks with 8 intervals; for PRE.mean and SNSR.mean, Quantile Breaks with 7 intervals were optimal; and for WIND.mean, Natural Breaks with 6 intervals were most effective. The spatial distribution of the driving factors after optimal discretization of NDVI.mean is shown in Fig. 7.

When performing geographical detector analysis on NDVI.rate from 2000 to 2022, the optimal discretization parameters for DEM are Quantile Breaks with 6 intervals; for LST.rate, SNSR.rate, and HFP.00–20, the optimal discretization parameters are Natural Breaks with 8 intervals; for PRE.rate and SW.rate, Quantile Breaks with 8 intervals provide the best results; and for WIND.rate, Natural Breaks with 7 intervals are optimal. The spatial distribution of the driving factors after optimal discretization of NDVI.rate is shown in Fig. 8.

Factor detection analysis

Factor detection analysis using the OPGD model was conducted to assess the importance of driving factors for vegetation NDVI.mean and NDVI.rate in the WSA, as shown in Fig. 9. For NDVI.mean, the importance of driving factors (q values) in descending order are: LST.mean > HFP.2020 > DEM > LCr > SW.mean > WIND.mean > PRE.mean > SNSR.mean. Among these, LST.mean, HFP.2020, DEM, and LCr are the primary driving factors, with explanatory power exceeding 35% for each. WIND.mean, PRE.mean, and SNSR.mean have relatively low explanatory power, each below 10%, indicating that these three factors have a minor influence on vegetation distribution in the WSA.

For NDVI.rate, the importance of driving factors (q values) in descending order are: LST.rate > LCr > HFP.00–20 > DEM > SW.rate > SNSR.rate > PRE.rate > WIND.rate. Among these, LST.rate, LCr, HFP.00–20, and DEM are the primary drivers of vegetation evolution, with explanatory power greater than 13% for each. PRE.rate and WIND.rate have relatively low explanatory power, each below 5%, indicating that these two factors have a minimal impact on vegetation evolution in the WSA. In summary, the distribution and evolution of vegetation in the WSA are primarily influenced by natural environmental factors (DEM and LST) and socio-economic factors (LCr and HFP).

Interaction detection analysis

Interaction detection analysis using the OPGD model was employed to explore whether the interaction of two driving factors enhances or weakens their explanatory power on vegetation and its evolution, as shown in Fig. 10. In the WSA, for both vegetation distribution and its evolution, the interaction of any two driving factors results in higher q values compared to single-factor interactions, indicating that interactions between factors predominantly enhance their effects in a bidirectional manner, without any independent interactions.

For NDVI.mean, the strongest interactions occur between LST.mean and other factors. The top four interactions, ranked by their q values from largest to smallest, are: LST.mean ∩ HFP.2020 (q = 72%) > LST.mean ∩ LCr (q = 71%) > LST.mean ∩ SNSR.mean (q = 68%) > LCr ∩ HFP.2020 (q = 67%). For NDVI.rate, the strongest interactions occur between LST.rate and other factors. The top four interactions, ranked by their q values from largest to smallest, are: LST.rate ∩ SW.rate (q = 49%) > LST.rate ∩ LCr (q = 48%) = LST.rate ∩ SNSR.rate (q = 48%) > LST.rate ∩ DEM (q = 46%). In summary, the interactions between driving factors strengthen the individual influence of each factor on vegetation distribution and its evolution.

Influence of primary driving factors

The OPGD model allows for a quantitative assessment of the relative importance of each driving factor. However, to further elucidate the specific influence and mechanisms of individual factors on vegetation dynamics, we employed violin plots. Based on the optimal discretization results from the OPGD model, violin plots were used to examine the effects of four primary drivers—LST.mean, HFP.2020, DEM, and LCr—on both NDVI.mean and NDVI.rate within the study area, providing a detailed visualization of their distributions and nonlinear relationships.

Figure 11 presents the influence of four primary driving factors on NDVI.mean. As shown in Fig. 11a, LST.mean demonstrates a nonlinear negative correlation with NDVI.mean in the WSA. As LST.mean increases, the median of NDVI.mean decreases nonlinearly. At the same time, the distribution range of NDVI.mean expands, and its dispersion increases, indicating a more complex distribution pattern of NDVI.mean in areas with higher LST.mean. Figure 11b illustrates that human footprint of 2020 (HFP.2020) has a negative correlation with NDVI.mean. A good linear relationship exists between the median of HFP.2020 and NDVI.mean. As human activity intensity increases, the distribution range of NDVI.mean gradually widens, dispersion increases, and concentration decreases. This suggests that in areas with intense human activities, the spatial differentiation of NDVI becomes more significant, reflecting a higher complexity in the ecosystem’s response to human activities. In Fig. 11c, DEM shows a nonlinear positive correlation with NDVI.mean. As DEM decreases, the distribution range of NDVI.mean broadens, with increased dispersion and reduced concentration. This indicates that low-altitude areas exhibit greater spatial differentiation in NDVI, and the vegetation distribution is more complex. Figure 11d demonstrates the relationship between land cover types and NDVI.mean. In the Stable forest region of the WSA, NDVI values show high values, high concentration, and low dispersion, indicating that vegetation cover is high, and vegetation growth is stable and well-developed. In contrast, the NDVI median in Stable grassland and Others regions is lower, with lower concentration and a tendency towards lower values, suggesting that the NDVI distribution in these areas is more complex, with some low outliers, exhibiting stronger spatial heterogeneity. This may be related to the complex vegetation cover types, environmental heterogeneity, and higher levels of human activity in these areas.

Figure 12 presents the influence of four primary driving factors on the changes in NDVI.rate. LST.rate in the WSA shows a nonlinear negative correlation with NDVI.rate. When LST.rate is negative and lower (i.e., in areas with significant cooling), the median of NDVI.rate is higher and greater than 0, indicating a more significant vegetation greening phenomenon. In areas with smaller absolute values of LST.rate, NDVI.rate shows lower dispersion and higher concentration, suggesting that NDVI.rate changes are more stable in these regions. In areas with significant increases in LST.rate, the median of NDVI.rate is below 0, and most of the data is distributed below 0, indicating a negative NDVI trend in warming areas, reflecting vegetation browning.

Figure 12b illustrates the influence of different land cover types on NDVI.rate. In Stable forest region, NDVI.rate shows lower positive values, high concentration, and low dispersion, indicating that vegetation changes are small and vegetation growth is stable. In contrast, in Stable grassland and Other regions, the NDVI median is higher, with lower concentration and a certain negative skew, suggesting that NDVI changes in these areas are more volatile and heterogeneous, with a few negative outliers. This indicates that greening and browning phenomena in the WSA primarily occur in these two types of land cover. Figure 12c shows the complex relationship between human footprint change intensity (HFP.00-20) and NDVI.rate from 2000 to 2020. From the distribution of the median of NDVI.rate, as HFP.00-20 increases, the median of NDVI.rate first increases and then decreases, while the dispersion continues to increase. This suggests that moderate to low human activity intensity may promote vegetation greening, while high-intensity human activity leads to more complex vegetation changes and may even trigger vegetation browning. These phenomena reflect the complexity of the ecosystem’s response to human activities in the WSA.

DEM shows a nonlinear negative correlation with NDVI.rate (Fig. 12d). As the DEM value increases, the median of NDVI.rate decreases, and the dispersion reduces. This indicates that NDVI changes in low-altitude areas exhibit greater differentiation, and the vegetation evolution process is more complex, potentially influenced by a combination of natural factors, climate change, and human activities.

Correlation between NDVI and land surface temperature (LST)

We calculated the correlation between the annual time series of NDVI and the annual time series of climate factors for each pixel in the WSA from 2000 to 2022. The proportions of significant correlations (p ≤ 0.05) for each factor are as follows: LST (32.1%), SW (17.6%), PRE (6.8%), WIND (5.3%), and SNSR (2.2%). Figure 13 shows the spatial distribution of the correlation between NDVI and LST, with significantly negative correlations corresponding to areas where vegetation NDVI has either significantly increased or decreased.

Considering the land cover types in the WSA, we selected three typical points and analyzed the relationship between NDVI and LST from a time-series perspective. Point A is located in the Stable grassland region. Between 2000 and 2022, NDVI at this point showed a continuous, stable increase, while LST gradually decreased. The correlation coefficient between them was -0.754. Point B is located in an area classified as Others. From 2009 to 2011, the land cover at this point changed from farmland to urban, with a significant decrease in NDVI. At the same time, the LST sequence showed a noticeable warming trend. Overall, NDVI at Point B decreased while LST increased, with a correlation coefficient of -0.631. Point C is located in the Stable forest region. The changes in both NDVI and LST at this point were smaller compared to Points A and B, with both showing a slow upward trend. The correlation coefficient here was 0.602.

Discussion

Spatiotemporal distribution features of NDVI

Between 2000 and 2022, vegetation coverage in the WSA has remained at a high level, displaying a significant increasing trend in NDVI values. The spatial distribution of the multi-year average NDVI in the WSA exhibits evident heterogeneity. Regions with high vegetation coverage (NDVI.mean ≥ 0.7) constitute approximately 89.1% of the area and are mainly located in the high-altitude Qinling and Daba mountain ranges, where forest and shrub-grassland are the primary land cover types (Fig. 3a). In contrast, areas with low vegetation coverage (NDVI.mean ≤ 0.6) account for about 3% of the area, concentrated around towns and transportation routes within the WSA, where intense human activities and high land-use intensity result in lower vegetation coverage. The vegetation coverage around the Danjiangkou Reservoir is relatively low, potentially due to rocky desertification and historical overgrazing in the region. These observations align with previous studies32,33.

The NDVI.mean and its trend vary significantly among different land cover types in the WSA. Stable forest region exhibits the highest vegetation coverage, with a NDVI.mean of 0.862 and a minimal change rate, with a mean NDVI.rate of 0.0026 per year. This stability is mainly attributed to the forest cover, humid climate, ample precipitation, high elevation, and minimal human interference in these areas. Stable grassland region has a NDVI.mean of 0.759 and a mean NDVI.rate of 0.0049 per year. These regions are primarily covered by shrub-grassland, with a humid climate, higher average temperatures, sufficient rainfall, and relatively high altitudes, although vegetation coverage remains high despite slightly greater human impact. Others land cover types have an NDVI.mean of 0.782 and a mean NDVI.rate of 0.0044 per year. This category includes urban areas, farmland, and regions that underwent land cover changes between 2000 and 2022, such as grassland transitioning to forest or farmland to grassland. These regions experience a humid climate, higher average temperatures, sufficient rainfall, lower elevations, and significant human activity. Both Stable grassland and Others exhibit a significant increasing trend in vegetation coverage, largely attributed to ecological protection and restoration projects implemented over recent decades, including aerial seeding, rocky desertification control, and the conversion of farmland to forest and grassland44, which have effectively promoted vegetation recovery and improvement in the WSA. In contrast, urban areas in the water source region (approximately 1.3%) display notable vegetation degradation, likely due to the impact of human activities associated with urbanization, particularly changes in land use intensity and patterns, as well as the increase in impervious surfaces, leading to reduced vegetation coverage.

Effects of driving factors on NDVI change

This study utilized the OPGD model to analyze the driving factors influencing vegetation and its changes within the WSA of the SNWD-C. Findings indicate that vegetation evolution in the source area results from multiple factors acting in combination, rather than being driven by a single variable. These factors include natural conditions, climate variability, and human activities.

The results from the Geographical Detector model indicate that LST has a relatively high q value (39.7%), suggesting that LST is the primary factor influencing vegetation evolution in the WSA. The spatial distribution of vegetation change in relation to the LST change rate reveals a significant negative correlation between vegetation and land surface temperature. Areas with improving vegetation coverage generally experience a decrease in LST, while areas with declining vegetation coverage tend to show an increase in LST. Vegetation contributes to cooling through mechanisms such as transpiration, shading, and reduced surface radiation, demonstrating a strong coupling between land surface temperature and vegetation evolution45,46. Furthermore, despite the humid climate and ample rainfall in the WSA, precipitation does not emerge as a primary driver of vegetation evolution. This finding contrasts with observations in arid and semi-arid regions, where precipitation plays a more significant role in shaping vegetation dynamics25.

Land cover type is another significant driver of vegetation evolution within the WSA. By examining the spatial distribution of vegetation evolution alongside land cover, it becomes evident that Stable forest region exhibits the highest vegetation coverage, with minimal NDVI change intensity, indicating stability. In comparison, Stable grassland and Others regions have slightly lower vegetation coverage but show a marked trend of vegetation increase. Although the Stable forest and Stable grassland did not change between 2000 and 2022, multiple water conservation and ecological restoration projects, such as the Qinling Ecological Restoration47 and the Yangtze River Basin Spatial Management Project48,49, have substantially enhanced vegetation structure and function, leading to improved forest and grassland protection in these areas. Consequently, vegetation in these regions has shown signs of improvement. The “Others” category includes farmland, urban areas, and areas with land cover changes between 2001 and 2022, leading to diverse vegetation evolution patterns. Urbanization, for instance, has encroached upon farmland and forest areas around cities, increasing impervious surfaces and reducing vegetation coverage, which has led to browning in some regions. In contrast, cropland vegetation in the Hanzhong Plain and the eastern WSA has significantly improved, suggesting that advances in farming techniques have facilitated greening in these areas2,6. Figure 5 illustrates the noticeable trend of converting cropland back to grassland and reforesting between 2001 and 2022, driven by water conservation and ecological protection projects. Between 2001 and 2022, forest and grassland areas increased by 20,149 km2 and 4,840 km2, respectively, greatly enhancing vegetation conditions. These findings confirm the positive impact of human interventions on the natural environment of the WSA2,5.

The terrain of the WSA, primarily consisting of mountains, valleys, and basins, also influences vegetation cover. The high-altitude Qinling and Daba Mountains, predominantly covered by forests and grasslands, experience limited human activity and support high vegetation coverage, with a stable growth trend influenced by ecological restoration projects. In contrast, valleys and basins at lower elevations, where agriculture and urban development are prominent, experience intense human activity, resulting in lower vegetation coverage and more drastic vegetation changes. This distinction further illustrates the substantial impact of human activity intensity on vegetation coverage changes in the WSA.

The interaction among driving factors also affects vegetation coverage changes27,29. Experimental results (Fig. 10) reveal that interactions between any two factors drive vegetation coverage more significantly than any single factor, consistent with prior studies25. Specifically, interactions between land surface temperature, land cover type, human footprint, and DEM exhibit the most substantial impact on vegetation coverage. This effect likely arises from spatial variations in human activities across land use types, which are further influenced by topography and land surface temperature, ultimately shaping the spatial pattern of vegetation coverage. The OPGD interaction analysis revealed that the combined effect of any two factors was greater than their individual effects, indicating synergistic enhancement in explaining vegetation patterns (Fig. 10). For example, the interaction between LST.mean and HFP.2020 (q = 72%) was the strongest for NDVI distribution, suggesting that temperature effects on vegetation are significantly modulated by human activity intensity. In areas with high human footprint (e.g., urban or intensive agriculture), elevated temperatures may exacerbate vegetation stress through heat islands and reduced water availability, whereas in cooler, less-disturbed regions, vegetation thrives.

Similarly, the interaction between LST.rate and LCr (q = 48%) for vegetation trends indicates that the impact of warming or cooling trends on vegetation growth depends on land cover. Ecologically, this implies that conservation policies should not address climate or human activities in isolation. For instance, afforestation efforts (LCr change) in regions experiencing warming trends (LST.rate) may require supplemental irrigation or careful species selection. For policymakers in the SNWD-C, these findings highlight the importance of integrated land-use planning that accounts for microclimatic conditions. Areas with high interaction values (e.g., urban heat islands with significant greening potential) could be prioritized for interventions such as green infrastructure development to mitigate LST and enhance vegetation cover, thereby safeguarding water quality and quantity in the reservoir.

Effects of ecological restoration projects on NDVI change

To validate the conclusions drawn from Sen’s slope trend analysis, four regions with significant vegetation changes in the WSA were selected to compare NDVI changes between 2001 and 2022 (Fig. 14). Hanzhong, Ankang, and Shangluo (regions 1–3 in Fig. 14) were the first regions in Shaanxi Province to implement ecological restoration projects, including reforestation and grassland restoration. Key ecological initiatives, such as afforestation and forest closure, have focused on the northern Qinling Mountains in Hanzhong, the southern and northern Qinba Mountains in Ankang, and the southwestern Liuling Mountains in Shangluo. Notably, the Liuling Mountains in southwestern Shangluo now host China’s largest northern aerially sown forest, covering millions of acres. Compared to 2001, NDVI in these three regions increased significantly by 2022. Furthermore, Fig. 14 shows that urban NDVI in these areas has decreased significantly, whereas non-urban areas (e.g., croplands) exhibit substantial NDVI increases. This suggests that agricultural advancements, particularly in scientific breeding, fertilization, irrigation, and pest control, have significantly improved vegetation coverage in farmland areas, consistent with findings from Piao et al.2.

Region 4 in Fig. 14 is located around the Danjiangkou Reservoir, where steep slopes, thin topsoil, and erosion-prone areas result in lower vegetation coverage and an ecologically fragile environment. Historically, this area has faced issues of rocky desertification and overgrazing, leading to low NDVI values in 2001. As ecological restoration efforts progressed, cities like Danjiangkou and Shiyan launched comprehensive projects to combat rocky desertification, which included afforestation, forest closure, conversion of farmland to forest, and forestland management. These measures have significantly enhanced the ecological environment around the reservoir. For instance, Shigu Town in Danjiangkou launched a rocky desertification transformation project spanning over 6,000 acres, increasing vegetation coverage to 70% and substantially improving the region’s vegetation conditions.

Our findings strongly align with and validate the existing SNWD-C management practices focused on ecological restoration, such as afforestation and forest closure, as evidenced by the significant greening trends in stable grassland and reforested areas (‘Others’ category) (Figs. 5b, 6b, 14). The results provide a spatially explicit scientific basis for optimizing these practices. For conservation planners, the maps of NDVI trends and driver importance (Figs. 5, 9) can be used to identify priority zones for intervention: Degradation hotspots (urban areas, Fig. 5b): Policies should enforce strict urban greening mandates and create cooling green corridors to counter heat island effects and vegetation decline. High-potential greening areas (mid-low altitude grasslands, Fig. 5b): Practices like controlled grazing and planting climate-resilient native species can be encouraged to accelerate greening and soil conservation. Stable but vulnerable forests (high altitudes, Figs. 5b, 6b): Management should focus on protection and monitoring rather than active intervention, ensuring the stability of this crucial water conservation zone.

Limitations and future perspectives

Vegetation plays a crucial role in regulating the exchange of carbon, water, and energy between land and the atmosphere, an essential aspect of global environmental and climate change research3,4,5. While this study offers valuable insights into vegetation evolution and its driving mechanisms, several limitations exist that future research should address.

First, challenges in data collection, downscaling, and a lack of ground validation data limit the comprehensiveness and accuracy of selected driving factors, potentially affecting the completeness and precision of the results. Additionally, the OPGD model did not fully explore the mechanisms through which individual driving factors impact vegetation or clarify the interactions between multiple drivers, constraining an in-depth understanding of vegetation evolution processes. Moreover, although MODIS NDVI data are reliable, their low spatial resolution and short temporal span restrict precise vegetation analysis.

To overcome these limitations, future research should leverage high-resolution remote sensing data, such as the Landsat and Sentinel-2 series provided by the GEE platform. Combining these data with geographically weighted models and interpretable deep learning approaches could yield a deeper understanding of vegetation change mechanisms. Adopting a broader range of driving factors and high-resolution data can enhance the accuracy and robustness of vegetation evolution studies.

Conclusions

This study comprehensively analyzed vegetation cover dynamics within the WSA of the SNWD-C, spanning from 2000 to 2022 using MODIS NDVI data. Employing methods like Sen’s slope estimator, the Mann–Kendall test, and coefficient of variation analysis, we assessed vegetation trends and integrated various datasets, such as DEM, LCr, LST, HFP, PRE, SNSR, WIND and SW. By leveraging the OPGD model and advanced statistical visualization techniques, we identified the primary drivers of vegetation change and examined the roles of surface temperature variations and ecological restoration efforts. The findings showed that the WSA consistently features high vegetation cover, with significant greening trends, especially in forested and shrub-covered areas at lower elevations, while urban regions and areas with dense transport networks exhibited signs of degradation. The analysis revealed that LST and HFP were key drivers of vegetation patterns, with their interactions amplifying the effects. Notably, a nonlinear inverse relationship was observed between LST changes and vegetation trends: cooling areas experienced significant greening, whereas warming regions tended to brown. These findings underscore the intricate interplay of climatic and anthropogenic influences on vegetation, offering crucial insights for ecological conservation and sustainable water resource management in the WSA.

Data availability

All data used in this study were from published resources as described in the Study area and data sources.

References

Bonan, G. B., Pollard, D. & Thompson, S. L. Effects of boreal forest vegetation on global climate. Nature 359, 716–718 (1992).

Piao, S. L. et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 14–27 (2020).

Baudena, M., D’Andrea, F. & Provenzale, A. A model for soil–vegetation–atmosphere interactions in water-limited ecosystems. Water Resour. Res. 44, W12429 (2008).

Duveiller, G., Hooker, J. & Cescatti, A. The mark of vegetation change on Earth’s surface energy balance. Nat. Commun. 9, 679 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Vegetation greenness in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 241–243 (2024).

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 791–795 (2016).

Chen, C. et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2, 122–129 (2019).

Priya, R. S. & Vani, K. Vegetation change detection and recovery assessment based on post-fire satellite imagery using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 12611 (2024).

Pettorelli, N. et al. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 503–510 (2005).

De Falco, N. et al. Geodiversity impacts plant community structure in a semi-arid region. Sci. Rep. 11, 15259 (2021).

Zeng, Y. et al. Optical vegetation indices for monitoring terrestrial ecosystems globally. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 477–493 (2022).

Mehmood, K. et al. Analyzing vegetation health dynamics across seasons and regions through NDVI and climatic variables. Sci. Rep. 14, 11775 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. An evaluation framework for quantifying vegetation loss and recovery in response to meteorological drought based on SPEI and NDVI. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167632 (2024).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27 (2017).

Tamiminia, H. et al. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 164, 152–170 (2020).

Jiang, H. et al. Determining the contributions of climate change and human activities to vegetation dynamics in agro-pastoral transitional zone of northern China from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 134871 (2020).

Ma, M., Wang, Q., Liu, R., Zhao, Y. & Zhang, D. Effects of climate change and human activities on vegetation coverage change in northern China considering extreme climate and time-lag and-accumulation effects. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160527 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Quantitatively analyzing the driving factors of vegetation change in China: Climate change and human activities. Ecol. Inform. 82, 102667 (2024).

Sen, P. K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 63, 1379–1389 (1968).

Mann, H. B. Non-parametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13, 245–259 (1945).

Liu, C. et al. Detection of vegetation coverage changes in the Yellow River Basin from 2003 to 2020. Ecol. Indic. 138, 108818 (2022).

Zhao, X., Tan, S., Li, Y., Wu, H. & Wu, R. Quantitative analysis of fractional vegetation cover in southern Sichuan urban agglomeration using optimal parameter geographic detector model, China. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111529 (2024).

He, X., Zhang, L., Lu, Y. & Chai, L. Spatiotemporal variations of vegetation and its response to climate change and human activities in arid areas—A case study of the Shule River Basin, northwestern China. Forests 15, 1147 (2024).

Evans, J. & Geerken, R. Discrimination between climate and human-induced dryland degradation. J. Arid Environ. 57, 535–554 (2004).

Zhou, Q., Chen, W., Wang, H. & Wang, D. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors analysis of fractional vegetation coverage in the arid region of northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 954, 176271 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun region. China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24, 107–127 (2010).

Song, Y., Wang, J., Ge, Y. & Xu, C. An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: Cases with different types of spatial data. GISci. Remote Sens. 57, 593–610 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Statistical modeling of spatially stratified heterogeneous data. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 114, 499–519 (2024).

Zou, F. et al. Spatiotemporal changes and driving analysis of ecological environmental quality along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway using Google Earth Engine—A case study covering Xining to Jianghe stations. Remote Sens. 16, 951 (2024).

Long, D. et al. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nat. Commun. 11, 3665 (2020).

Zhou, Z., Zeng, Y., Zhang, L., Du, X. & Wu, B. Remote sensing monitoring and analysis of fractional vegetation cover in the water source area of the middle route of projects to divert water from the south to the north. Remote Sens. Land Resour. 92, 70–76 (2012).

Gao, W. W. et al. Forest dynamic monitoring by remote sensing from 2000 to 2015 in the water source area of the South-to-North Water Diversion Project. Sci. Silvae Sin. 55, 97–107 (2019).

Li, P., Jiang, Y., Qi, P. & Wang, L. Spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of vegetation in water source area of the middle route project of South-to-North Water Diversion. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 39, 49–55 (2022).

Zheng, J., Yin, Y. & Li, B. A new scheme for climate regionalization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 65, 3–12 (2010).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land, a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Friedl, M. A. et al. MODIS Collection 5 global land cover: Algorithm refinements and characterization of new datasets. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 168–182 (2010).

Pekel, J. F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Belward, A. S. High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature 540, 418–422 (2016).

Mu, H. et al. A global record of annual terrestrial human footprint dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 9, 176 (2022).

Kamran, M. & Yamamoto, K. Evolution and use of remote sensing in ecological vulnerability assessment: A review. Ecol. Indic. 148, 110099 (2023).

Wang, J. F., Zhang, T. L. & Fu, B. J. A measure of spatial stratified heterogeneity. Ecol. Indic. 67, 250–256 (2016).

Schober, P., Boer, C. & Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 126, 1763–1768 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Li, X. & Liu, Y. Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995–2015. Land Use Policy 99, 105048 (2020).

Kennedy, R. E. et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of forest disturbance and regrowth within the area of the Northwest Forest Plan. Remote Sens. Environ. 122, 117–133 (2012).

Cai, Y. et al. Vegetation cover changes in China induced by ecological restoration-protection projects and land-use changes from 2000 to 2020. CATENA 217, 106530 (2022).

Deng, C., Zhang, B., Cheng, L., Hu, L. & Chen, F. Vegetation dynamics and their effects on surface water-energy balance over the Three-North region of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 275, 79–90 (2019).

Zhao, F. et al. The role of climate change and vegetation greening on evapotranspiration variation in the Yellow River Basin, China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 316, 108842 (2022).

Li, J. Y. et al. Ecological civilization construction at Qinling Mountains in the new era. J. Nat. Resour. 36, 2449–2463 (2021).

Gu, W. M., Zhou, J. X., Wu, J. H., Zhou, T. L. & Liu, Y. G. Artificial afforestation technology for rocky desertification control in Xichuan County of South-to-North Water Diversion Project. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 3, 44–48 (2018).

Fu, B. J. Several key points in territorial ecological restoration. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 36, 64–69 (2021).

Funding

This research has been funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42074094); the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (Grant Nos. 242102321123 and 242102320345); the Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (Grant No. 25A420006); Start-up Project for High-level Talent Recruitment, Henan University of Urban Construction (Grant No. K-Q2024012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W.: Methodology, writing-review & editing, validation, funding acquisition, software. Y.J.: Writing-review & editing, validation, supervision, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Jiang, Y. Vegetation dynamics and associated driving mechanisms in the water source area of the central route of the South-to-North Water Diversion, China during 2000–2022. Sci Rep 15, 42079 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26094-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26094-x