Abstract

Understanding the interdecadal periodicity of large-scale seismic activities is critical for improving long-term earthquake forecasting, yet it remains constrained by the limited duration of instrumental records. Here we apply high-resolution spectral analysis to a millennia-long catalog of historical earthquakes in China, extending to 1831 BC. The most pronounced seismic activities occurred during the 1620–1630 s AD, a period that coincided with a major regime shift that preceded the collapse of the Chinese Ming Dynasty. High-resolution spectral analysis was performed on the historical dataset to identify robust ~ 10- and ~ 50-year periodicities in seismic frequency. The ~ 10-year periodicity exhibits a significant lagged correlation with solar (sunspot) activity, while the ~ 50-year periodicity aligns with multidecadal variability in solar irradiance, sea level fluctuations, and tropical sea surface temperatures (SSTs). We propose that enhanced solar irradiance modulates the mean state and variability of tropical Pacific climate modes, particularly the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is associated with changes in inter-basin sea-level gradients and crustal stress regimes. These findings reveal a potential coupling between external solar forcing and internal climate variability in shaping seismic cyclicity at interdecadal scales, offering a novel framework for assessing long-term earthquake risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Forecasting earthquake probabilities over interdecadal timescales (10–100 years) is essential for improving seismic hazard assessment, enhancing infrastructure resilience, and guiding disaster preparedness efforts1,2,3. Traditionally, regional earthquake recurrence intervals have been identified primarily through tectonic stress accumulation and release4,5,6. However, large-scale seismic cycles spanning multiple regions and longer durations remain poorly understood7,8,9. Most existing studies of seismic periodicity rely on earthquake catalogs covering roughly a century, which is insufficient for capturing cycles on interdecadal timescales. Therefore, identifying longer-term periodicities requires extensive historical earthquake records spanning several centuries.

China, located between the Circum-Pacific and Alpine-Himalayan seismic zones, is one of the world’s most earthquake-prone countries1,3,10. It experienced the deadliest earthquake ever recorded, the 1556 AD Shaanxi earthquake that caused approximately 830,000 fatalities11. China maintains unique historical earthquake records extending back to 1831 BC12. This extensive documentation provides an exceptional opportunity to investigate long-term seismic periodicities and their potential links to external drivers and internal feedbacks. Nevertheless, historical seismic records are often incomplete and unevenly distributed, complicating periodicity analyses. In this study, we employ rigorous analytical methods to identify interdecadal seismic periodicities and explore their relationships with solar irradiation and internal climate variability associated with major oceanic modes.

Results

Spatiotemporal evolution of seismicity since 1500 AD

The historical earthquake dataset for China comprises records of 6,055 destructive earthquakes (M ≥ 4.0) occurring from 1831 BC to 1970 AD12. Magnitude and intensity prior to 1900 AD were inferred from historical documents, while post-1900 AD events were instrumentally recorded. Notably, 89.9% of these earthquakes were documented after 1900 AD, reflecting changes in recording practices. Thus, this study focuses on pre-1900 AD historical earthquake records, which offer more consistent criteria over a longer temporal span. We prioritize earthquake frequency over magnitude or intensity, as frequency estimates from historical documents are considered more reliable.

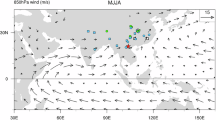

Detailed earthquake records become more abundant after the Ming Dynasty (1368 − 1644 AD), largely due to the compilation of local chronicles12. Accordingly, we analyzed data from 1500 to 1900 AD. Within this interval, 137 years (34.2%) had no recorded earthquakes, while most earthquake-active years recorded one (32.9%) or two (20.0%) events. The year 1624 AD marked the highest frequency, with nine recorded earthquakes. The 1620–1630 s AD was among the most seismically active decades, accounting for ~ 12.1% of all events during the study period. The heightened seismic activity coincides notably with one of the driest epochs recorded over the past five centuries across northern China and the broader Pacific Rim13,14. The convergence of frequent seismic events and severe megadroughts likely exacerbated socio-economic stress, increasing agricultural burdens, undermining disaster relief efforts, and ultimately contributing to widespread social unrest and the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644 AD. Historically documented earthquakes predominantly occurred along China’s major seismic belts2,15, notably the southeastern coastal region, southwestern China and the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, as well as the Taihang and Yan Mountains in northern China (Fig. 1b and Fig. S1). To explicitly address potential spatial recording bias, we delineated two politically centralized core regions—North China (36–41° N, 114–120° E) and East China (30–34° N, 118–121° E)—for subsequent exclusion tests (Fig. S4), enabling direct evaluation of periodicity robustness outside these cores (Fig. S5) and Fig. 2.

Periodicities of historical earthquake activity in China. Lomb–Scargle periodograms of annual earthquake counts for three periods: (a) 1831 BC–1900 AD, (b) 1300–1900 AD, and (c) 1500–1900 AD. Significant spectral peaks at ~ 10 years, ~ 54 years, and ~ 137 years (p < 0.05) indicate prominent multidecadal cycles.

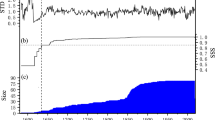

Periodicity of seismicity and its correlation with solar irradiation

Due to advances in observational techniques, the number of recorded earthquakes shows an increasing trend, which is reflected in the residual as a long-term upward tendency. The apparent sharp decline after 1850 mainly results from endpoint effects and truncation of long-period components, causing boundary fluctuations rather than a true physical trend (Fig. S2). To isolate intrinsic periodicities, we detrended the earthquake frequency data before spectral analysis. The Lomb–Scargle periodogram consistently identified significant ~ 10-, ~ 50-, and ~ 135-year periodicities across three temporal intervals (1831 BC–1900 AD, 1300–1900 AD, and 1500–1900 AD), all independently confirmed via Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) analysis (Fig. S3). The ~ 10-year and ~ 50-year cycles were particularly prominent during the late Ming period (1610–1650 AD), when seismic activities peaked (Fig. S3). We recomputed Lomb spectra after excluding the North core (Fig. S5c) and both cores (Fig. S5d); the principal bands persist. We also verified magnitude-threshold insensitivity by repeating the analysis for M < 5 and M ≥ 5 subsets (Fig. S5a–b), which consistently reproduce these bands.

We further examined the relationship of ~ 10-year seismic cycle with the ~ 11-year solar (sunspot) cycle16. Due to the irregularity and sparseness of historical data, we applied a variance-weighted method to reduce heteroskedastic noise17. A significant positive correlation (r = 0.32, p < 0.05) was observed, with seismicity lagging sunspot peaks by ~ 4 years (Fig. 3a). This correlation was evidenced by close matches between high solar activity and increased seismicity with a consistent temporal lag (Fig. 3b). Additionally, analysis of unfiltered seismic data demonstrated a clear relationship between seismic activity and solar irradiation (Fig. 3c). Notably, seismic activity significantly decreased during periods of solar minima, such as the Maunder Minimum (1645–1715 AD) and the Dalton Minimum (1790–1820 AD)18,19. Conversely, the highest seismicity coincided with a period of elevated solar irradiance preceding the Maunder Minimum (approximately 1570–1630 AD). While previous short-term observational studies hinted at solar-seismic linkages20, our study provides a robust, long-term empirical evidence supporting this relationship.

Relationships between ~ 10-year cyclic seismicity and solar activity. (a) Lead–lag correlations between 9–11-year filtered earthquake frequencies and sunspot numbers. (b) Comparison of time series with sunspots leading seismicity by 4 years, where the strongest positive correlation is observed (r = 0.32, p < 0.05). (c) Temporal comparison of unfiltered earthquake frequency and reconstructed solar irradiance. Positive values in (a) indicate that sunspot activity leads seismicity; negative values suggest the reverse.

Multidecadal periodicity of seismicity and its modulators

We next analyzed the ~ 50-year seismic cycle by examining correlations with multidecadal geophysical parameters and internal climate modes. Periods of increased seismicity moderately coincided with intervals of enhanced Earth rotation speed, indicated by reductions in reconstructed Length of Day (LOD), resulting in a significant correlation (r = 0.22, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). Earth’s rotational dynamics may influence global stress fields and deep-layer coupling, thus affecting seismicity21. Additionally, seismic activity exhibited a strong positive correlation with reconstructed sea-level changes (r = 0.56, p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). Variations in sea levels alter crustal equilibrium and plate stress conditions, directly influencing seismic potential22. A significant correlation (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) was also observed between seismicity and geomagnetic declination, suggesting seismic influences via electromagnetic induction, fluid-rock coupling, and ionospheric interactions23. While previous studies identified these links primarily on shorter temporal scales23, our findings extend them robustly into multidecadal timescales.

Relationships between ~ 50-year seismic fluctuations and geophysical parameters. Comparisons of filtered earthquake variability with: (a) Length of Day (LOD), representing Earth’s rotational speed; (b) Global sea level changes; and (c) Geomagnetic declination (Dec). All the variables were linearly detrended to highlight their multidecadal coherence with seismic activity.

Relationships with two major oceanic climate modes were investigated, including the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO)24,25,26. Correlation results indicated no significant association with the AMO (Fig. 5a), likely due to geographic distance. Hydroclimate variations of the entire Pacific area show synchronous patterns on multidecadal scales (> 50 years)14, which is termed as the Multidecadal Pacific Oscillation (MPO)27. Unlike the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which emphasizes decadal variability in the North Pacific extratropics, the MPO reflects basin-wide interdecadal variability centered in the tropics and extending into the Southern Ocean, leading to stronger sea-level loading and broader stress impacts along Pacific margins27. The MPO also showed a relatively strong correlation with seismicity (r = 0.38, p < 0.05) (Fig. 5b). Similarly, multidecadal ENSO variability exhibited a notable positive correlation with seismicity (r = 0.31, p < 0.05; Fig. 5c).

Relationships between ~ 50-year periodic earthquake activity and major oceanic climate modes. Comparisons of seismicity with: (a) Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO); (b) Multidecadal Pacific Oscillation (MPO); (c) El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO); and (d) ENSO multidecadal variability (standard deviation over a 51-year moving window).

The strongest correlation (r = 0.51, p < 0.05) was identified between seismic activity and multidecadal ENSO variability, measured by running 51-year standard deviation windows (Fig. 5d). Periods of reduced seismicity aligned closely with intervals of diminished ENSO variability (e.g., ~ 1590 s AD and ~ 1680–1700 s AD), while increased seismicity coincided with heightened ENSO variability (e.g., ~ 1730–1810 s AD, post-1870s AD).

Discussion

Understanding seismic periodicities at large spatial scales is critical for effective disaster risk reduction and strategic mitigation planning. However, accurately detecting long-term earthquake cycles remains challenging due to the incompleteness and regional biases of historical earthquake records. For example, the apparent scarcity of seismic events in remote regions like the Tibetan Plateau likely reflects limited documentation rather than actual tectonic quiescence. In contrast, areas near historical political centers, such as the Taihang and Yan Mountains, display disproportionately high frequency due to greater administrative presence and more consistent record-keeping. This underscores the necessity of critically evaluating spatial data gaps when interpreting long-term seismic trends.

Although the existence and driving mechanisms of large-scale seismic periodicities are still debated, any progress in deciphering these patterns carries significant scientific and practical implications. This study presents robust empirical evidence for interdecadal seismic periodicities (~ 10 and ~ 50 years) based on long-term historical earthquake records in China. These periodicities are geographically widespread, extending beyond individual fault zones or local regions4,5,6, suggesting that large-scale tectonic processes and external forcings may play critical roles. Notably, the detection of these cycles was strongest during the late Ming period (1610–1650 AD), which coincided with the highest recorded seismic activity. This period aligns with heightened socio-political instability and severe droughts, indicating potential associations between seismicity, climate stressors, and human vulnerability. Nevertheless, additional data from other regions and longer historical timelines are needed to verify the consistency of these interdecadal patterns.

Our results reveal a stronger correlation between multidecadal seismic cycles in China and climatic variability in the tropical Pacific Ocean, compared to other oceanic regions. This linkage appears to be influenced in part by solar irradiance. Increased solar radiation typically warms the eastern Pacific, producing a La Niña–like pattern28,29. Such conditions may explain the negative correlation observed between multidecadal seismicity and solar irradiation, as well as with ENSO phases. The ~ 10-year seismic cycle shows a statistically significant lagged correlation with the ~ 11-year solar cycle, suggesting that elevated solar activity precedes increased seismicity by about four years, possibly due to delayed lithospheric stress adjustments driven by solar-forced ocean–atmosphere circulation changes. Furthermore, periods of heightened solar irradiance often coincided with increased ENSO variability30,31, which aligns with the strong positive correlation identified between seismic activity and ENSO variability. These findings are consistent with a potential delayed geophysical response to solar forcing, possibly mediated by changes in atmospheric circulation or ocean heat distribution.

Long-term connections between solar maxima and elevated seismic activity have been reported in historical records from the Mediterranean over the past seven centuries20. ENSO is widely recognized as a dominant mode of climate variability with global influence4,32,33,34, and has been linked to seismic activity on interannual timescales35,36. Our study extends this understanding by indicating an association between ENSO variability on seismicity at multidecadal scales. In particular, multidecadal ENSO variability exhibits the strongest correlation with seismicity (r = 0.51), with seismic peaks aligning with periods of high ENSO variance (e.g., post-1730s AD and post-1870s AD), and lulls during times of weak ENSO fluctuations (e.g., ~ 1590 s AD and ~ 1680–1700 s AD). These results suggest that tropical Pacific Ocean–atmosphere dynamics, especially those associated with ENSO, may be centrally associated with variations in long-term seismic activity. ENSO sets up an east–west “see-saw” in tropical Pacific sea level. The resulting ocean-bottom pressure changes (kPa-scale) load and unload coastal and subduction faults, bending the plate and changing the pressure on faults and their pore fluids, which can nudge already stressed faults toward or away from failure37,38. This approach may also be applicable to other regions with relatively long and continuous historical earthquake records, for example parts of the Mediterranean, Iran, or Mexico, although differences in data coverage and reliability would need to be considered.

While this study focuses primarily on climatic influences on seismicity, the reverse relationship of the climatic impacts on seismic events remains poorly understood and difficult to investigate. On geological timescales, tectonic activity influences climate mainly through processes such as enhanced silicate weathering, which lowers atmospheric CO₂39,40. On shorter timescales, such effects are typically seen through volcanic eruptions, which inject aerosols into the stratosphere and induce temporary global cooling41,42. Emerging evidence suggests that major eruptions may also trigger longer-lasting, multidecadal climate anomalies26. Future work should explore whether seismic events—especially large submarine earthquakes—could similarly disrupt oceanic circulation patterns and produce climate responses comparable to those caused by major volcanic eruptions. Additionally, improved geophysical models could help determine whether internal Earth processes—such as variations in Earth’s rotation speed, geomagnetic field strength, or crustal stress from sea-level change—further mediate the climatic–seismic interactions described here. Sustained periods of elevated solar irradiance, especially when accompanied by enhanced tropical Pacific variability, may precede intervals of increased seismicity, while prolonged solar minima may correspond to reduced seismic activity.

In conclusion, we applied rigorous methodologies to identify consistent interdecadal seismic periodicities (~ 10 and ~ 50 years) from historical earthquake records in China. These cycles remain robust across different periods and analytical approaches. Our findings suggest that these periodicities are associated with both external solar forcing and internal climatic variability, particularly the tropical Pacific modes. Enhanced solar irradiance likely contributes to increased ENSO variability, which could be linked to changes in crustal stress and seismic potential. These results underscore the importance of incorporating tropical Pacific variability into future assessments of interdecadal seismicity. Earthquake prediction models that integrate both external and internal climatic drivers may significantly improve long-term seismic hazard forecasting and preparedness strategies. This relationship also provides useful context for extreme event attribution and for broader long-term seismic hazard assessments.

Methods

Data

The earthquake data is sourced from the Catalogue of China’s Earthquakes12,, which synthesizes diverse historical sources, including ancient documents, local chronicles, and stone inscriptions. This comprehensive dataset provides detailed information on earthquake occurrence times, epicenter locations, magnitudes, intensities, and reported damage.

Solar irradiance reconstructions utilized herein were based on cosmogenic nuclide records (14 C and 10Be isotopes), exhibiting broadly consistent patterns over the analyzed historical periods18,19. The AMO and ENSO reconstructions over the past centuries were derived from a synthesized reconstruction from a number of annually resolved reconstructions from multi-proxies43. The geomagnetic declination data are derived from the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF) model, which provides global field parameters from 1590 to the present. The sea-level reconstruction is taken from Jevrejeva et al.44, which documents long-term global sea-level changes.

Statistical methods

To detect periodicities within irregularly sampled historical earthquake records, we first detrended the annual earthquake count series using Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (loess). The smoothed trend was subtracted from the raw counts, yielding residual anomaly series with zero mean, which were subsequently standardized by their standard deviation. This procedure was applied consistently across all three intervals (1831 BC–1900, 1300–1900, and 1500–1900) to ensure comparability and to minimize the influence of non-stationary data density or secular trends. We then primarily applied the Lomb–Scargle periodogram45,46. This spectral analysis technique estimates power spectra directly by fitting sinusoidal functions to irregularly spaced data without necessitating interpolation or resampling, thus providing reliable periodicity detection despite data gaps and uneven temporal resolution.

For further verification and signal decomposition, we employed Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) to extract the dominant multi-scale oscillatory modes of seismic frequency. EEMD extends the traditional EMD by introducing white noise and ensemble averaging, which effectively alleviates mode mixing and improves the robustness of signal decomposition47. This method has been widely applied in geophysical and climatological studies, for example in detecting interdecadal variability in climate records48. Additionally, we utilized Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) analysis49 to assess variations in specific periodic components within nonstationary seismic sequences over different historical intervals. By applying a sliding window across the data series, STFT provides a detailed time-varying spectral characterization, effectively capturing transient oscillatory behavior within historical seismic records. When assessing correlations between seismicity and external variables (Length of Day, global sea level, geomagnetic declination, and major climate modes such as AMO, MPO, and ENSO), we used band-pass filtered series. Specifically, climate indices were processed with a 50-year Butterworth filter to highlight interdecadal to multidecadal variability, and the same filtering strategy was applied to the geophysical variables to ensure consistency. Collectively, these complementary statistical methodologies ensure robust and reliable identification of seismic periodicities, despite the inherent challenges posed by historical data limitations.

Data availability

The data and code used in this study can be found at http://rh1.xx925.vip/w/Tp4yEd.

References

Parsons, T., Ji, C. & Kirby, E. Stress changes from the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake and increased hazard in the Sichuan basin. Nature 454, 509–510 (2008).

Schaff, D. P. & Richards, P. G. Repeating seismic events in China. Science 303, 1176–1178 (2004).

Shen, Z. K. et al. Slip maxima at fault junctions and rupturing of barriers during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Nat. Geosci. 2, 718–724 (2009).

Li, Q., Tullis, T. E., Goldsby, D. & Carpick, R. W. Frictional ageing from interfacial bonding and the origins of rate and state friction. Nature 480, 233–236 (2011).

Arvidsson, R. Fennoscandian earthquakes: whole crustal rupturing related to postglacial rebound. Science 274, 744–746 (1996).

Brenguier, F. et al. Postseismic relaxation along the San Andreas fault at parkfield from continuous seismological observations. Science 321, 1478–1481 (2008).

Anagnostopoulos, G. et al. The sun as a significant agent provoking earthquakes. Eur. Phys. J. Special Top. 230, 287–333 (2021).

Marchitelli, V., Harabaglia, P., Troise, C. & Natale, G. D. On the correlation between solar activity and large earthquakes worldwide. Sci. Rep. 10, 11495 (2020).

Love, J. J. & Thomas, J. N. Insignificant solar-terrestrial triggering of earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 1165–1170 (2013).

Cai, J. et al. Three-Dimensional electrical structure beneath the epicenter zone and seismogenic setting of the 1976 Ms7. 8 Tangshan Earthquake, China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102291 (2023).

Li, B., Sørensen, M. B. & Atakan, K. Coulomb stress evolution in the Shanxi rift system, North China, since 1303 associated with coseismic, post-seismic and interseismic deformation. Geophys. Supplements Monthly Notices Royal Astron. Soc. 203, 1642–1664 (2015).

Gu, G. The Catalogue of Chinese Earthquakes. (Science Publishing House, 1983).

Chen, F. et al. Coupled Pacific rim megadroughts contributed to the fall of the Ming dynasty’s capital in 1644 CE. Sci. Bull. 69, 3106–3114 (2024).

Fang, K. et al. Synchronous multi-decadal tree-ring patterns of the Pacific areas reveal dynamics of the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) since 1567. Environmental Research Letters (2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa9f74

Li, S., Mooney, W. D. & Fan, J. Crustal structure of Mainland China from deep seismic sounding data. Tectonophysics 420, 239–252 (2006).

Clette, F., Svalgaard, L., Vaquero, J. M. & Cliver, E. W. Revisiting the sunspot number: A 400-year perspective on the solar cycle. Space Sci. Rev. 186, 35–103 (2014).

Fano, U. Ionization yield of radiations. II. The fluctuations of the number of ions. Phys. Rev. 72, 26 (1947).

Delaygue, G. & Bard, E. An Antarctic view of Beryllium-10 and solar activity for the past millennium. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-00010-00795-00381 (2010).

Bard, E., Raisbeck, G., Yiou, F. & Jouzel, J. Solar irradiance during the last 1200 years based on cosmogenic nuclides. Tellus B. 52, 985–992 (2000).

Georgieva, K., Kirov, B. & Dimitar, A. On the relation between solar activity and seismicity on different time-scales. J. Atmospheric Electricity. 22, 291–300 (2002).

Pang, G. & Koper, K. D. Excitation of earth’s inner core rotational Oscillation during 2001–2003 captured by earthquake doublets. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117504 (2022).

Bohnhoff, M., Martínez-Garzón, P. & Ben‐Zion, Y. Vol. 95 2571–2576 (Seismological Society of America, 2024).

Yusof, K. A. et al. Earthquake prediction model based on geomagnetic field data using automated machine learning. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5 (2024).

Enfield, D. B., Mestas-Nunez, A. M. & Trimble, P. J. The Atlantic multidecadal Oscillation and its relation to rainfall and river flows in the continental U. S. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2077–2080 (2001).

Wang, J. et al. Internal and external forcing of multidecadal Atlantic climate variability over the past 1,200 years. Nat. Geosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO2962 (2017).

Mann, M. E., Steinman, B. A., Brouillette, D. J. & Miller, S. K. Multidecadal climate oscillations during the past millennium driven by volcanic forcing. Science 371, 1014–1019 (2021).

Dong, Z., Zhou, F., Zheng, Z. & Fang, K. Increased amplitude of the North Pacific Gyre Oscillation towards recent: evidence from tree-ring‐based reconstruction since 1596. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 6403–6412 (2022).

Mann, M. E. et al. Global signatures and dynamical origins of the little ice age and medieval climate anomaly. Science 326, 1256–1260 (2009).

Liu, J., Wang, B., Cane, M. A., Yim, S. Y. & Lee, J. Y. Divergent global precipitation changes induced by natural versus anthropogenic forcing. Nature 493, 656–659 (2013).

Li, J. et al. El Niño modulations over the past seven centuries: Amplitude, Teleconnection, and the volcanic effect. Nat. Clim. Change. 3 https://doi.org/10.1038/NCLIMATE1936 (2013).

Fang, K., Chen, D., Li, J. & Seppä, H. Covarying hydroclimate patterns between monsoonal Asia and North America over the past 600 years. J. Clim. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-1113-00364.00361 (2014).

Fang, K. et al. ENSO modulates wildfire activity in China. Nat. Commun. 12, 1764. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21988-6 (2021).

Crosta, X. et al. Multi-decadal trends in Antarctic sea-ice extent driven by ENSO–SAM over the last 2,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 14, 156–160 (2021).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. science. 314. 1740–1745 (2006).

Keefer, D. K. & Moseley, M. E. Southern Peru desert shattered by the great 2001 earthquake: Implications for paleoseismic and paleo-El Niño–Southern Oscillation records. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, 10878–10883 (2004).

Kundu, B., Senapati, B., Chilukoti, N. & Sahoo, S. The potential role of El Niño-Southern Oscillation in triggering Greenland glacial earthquakes. Acta Geophysica, 73, 2287–2297 (2025).

Widlansky, M. J., Timmermann, A. & Cai, W. Future extreme sea level seesaws in the tropical Pacific. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500560 (2015).

Scholz, C. H., Tan, Y. J. & Albino, F. The mechanism of tidal triggering of earthquakes at mid-ocean ridges. Nat. Commun. 10, 2526 (2019).

Brantley, S. L., Shaughnessy, A., Lebedeva, M. I. & Balashov, V. N. How temperature-dependent silicate weathering acts as earth’s geological thermostat. Science 379, 382–389 (2023).

Bayon, G. et al. Accelerated mafic weathering in Southeast Asia linked to late neogene cooling. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf3141 (2023).

Bethke, I. et al. Potential volcanic impacts on future climate variability. Nat. Clim. Change. 7, 799–805 (2017).

Sigl, M. et al. Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature 523, 543–549 (2015).

Fang, K. et al. Oceanic and atmospheric modes in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans since the little ice age (LIA): towards a synthesis. Q. Sci. Rev. 215, 293–307 (2019).

Jevrejeva, S., Moore, J. C., Grinsted, A. & Woodworth, P. L. Recent global sea level acceleration started over 200 years ago? Geophysical Res. Letters 35, L08715 (2008).

Lomb, N. R. Least-squares frequency analysis of unequally spaced data. Astrophys. Space Sci. 39, 447–462 (1976).

Scargle, J. D. Studies in astronomical time series analysis. II-Statistical aspects of spectral analysis of unevenly spaced data. Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, vol. 263, Dec. 15, pp. 835–853. 263, 835–853 (1982). (1982).

Wu, Z. & Huang, N. E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: a noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 1, 1–41 (2009).

Ji, F., Wu, Z., Huang, J. & Chassignet, E. P. Evolution of land surface air temperature trend. Nat. Clim. Change. 4, 462–466 (2014).

B Allen, J. & R Rabiner, L. A unified approach to short-time fourier analysis and synthesis. Proc. IEEE. 65, 1558–1564 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Science Foundation of China (42425101, 41988101 and 42130507) and the Fujian Institute for Cross-Straits Integrated Development (LARH24JBO7).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KF, TOMethodology: ZZ, HWVisualization: ZZ, HWWriting—original draft: KF, ZZWriting—review & editing: KF, MH, JL, WT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, K., Zhao, Z., Wu, H. et al. Interdecadal seismic periodicity modulated by solar and oceanic variability revealed from Chinese historical documents. Sci Rep 15, 42168 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26103-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26103-z