Abstract

Dental chairs are essential for sustaining clinical care, yet their reliability in academic environments has rarely been quantified. This retrospective study, conducted across multiple clinics at Al-Andalus University for Medical Sciences (Tartous, Syria), integrated weekly usage logs, coded failure records, and equipment lifespan data to examine the relationship between workload and malfunction. Analysis revealed that prosthodontic and restorative clinics experienced the highest workloads and the greatest number of failures. Saliva ejectors, delivery systems, and control units accounted for most recurrent incidents, with a small subset of fault types responsible for the majority of breakdowns. The relationship between chair lifespan and fault frequency was generally weak, suggesting that age alone poorly predicts malfunction. Predictive modeling with random forest and linear regression demonstrated limited accuracy (R² ≈ 0.15) but revealed that case mix was a stronger driver of workload variation than calendar-related factors. Overall, the findings indicate that failure risk is shaped primarily by clinical specialization and workload intensity. Adapting maintenance strategies to actual usage and case profiles—rather than applying uniform schedules—may reduce downtime and improve patient flow. Expanding datasets and integrating real-time operational data could further strengthen predictive maintenance in academic dental settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental chairs form the core infrastructure of dental clinical settings and are directly responsible for enabling diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic procedures1,2,3. Their mechanical reliability, infection control safety, and ergonomic functionality are indispensable for delivering high-quality care4,5. However, in high-throughput academic clinics where chairs are subject to intensive usage across a range of case types and operators, failures and technical breakdowns are common yet poorly documented. The integration of equipment usage patterns, technical issue logs, and maintenance strategies into a unified assessment framework remains critically underexplored5,6.

Technical failures in dental units often stem from wear on hydraulics, actuators, control circuits, and water supply systems. Studies have identified recurring faults in various components, including delivery valves, programmable movement controls, water flow regulators, and light-curing modules5,6. Jin and Lu5,6 highlighted specific fault types in A-dec and Taurus dental units, noting that most failures are preventable through structured maintenance regimes. Similarly, Huang et al.7 emphasized that a significant proportion of failures are collective and recurring across multiple dental chairs, indicating systemic issues rather than isolated incidents. The failure of peripheral yet essential components, such as dental handpieces and light polymerization units, has also been highlighted as a source of treatment delays and compromised outcomes8,9.

Infection control is another major concern associated with dental unit operation, particularly in relation to water delivery systems. Research by Ni et al.1 and Niu et al.10 showed that microbial contamination in dental chair waterlines is widespread, driven by design flaws, stagnant flow, and irregular disinfection routines. Fujita et al.3 and Umer et al.4 demonstrated that decontamination technologies and continuous quality improvement (CQI) programs can significantly reduce microbial load, yet such interventions are rarely implemented across all chairs in large academic clinics. These findings reinforce the dual nature of dental chair vulnerabilities—both mechanical and microbiological—necessitating comprehensive maintenance oversight.

Beyond the technical and microbial aspects, operational patterns such as workload intensity and case diversity also influence equipment reliability. A five-year retrospective study by Siriwatana and Pongpanich2 linked dental adverse events to surges in patient volume, pointing to the interaction between service pressure and equipment failure rates. This is consistent with broader analyses by Alhussaini et al. and Alsalleeh et al.11,12, who found that maintenance frequency, technician preparedness, and workflow design play crucial roles in the safety and uptime of dental equipment. Institutions with underdeveloped maintenance infrastructures were more likely to report breakdowns, inefficiencies, and patient dissatisfaction.

The complexity of dental chair performance is amplified in university clinics, where teaching requirements intersect with clinical demands13. Prior work has noted that academic settings face particular challenges in balancing safety, reliability and educational variability, with human-factor issues (student training and supervision levels) implicated in technical wear and misuse14. Resource-utilisation studies similarly show that access to services and clinical preparedness shape throughput and, by extension, impose strain on equipment15,16. From a reliability-engineering standpoint, condition-based and prognostics-driven maintenance provide the conceptual basis for managing failure risk in clinical assets17,18,19. In healthcare operations, predictive-maintenance frameworks increasingly leverage device telemetry and workload signals to anticipate faults and reduce downtime; recent syntheses outline best practices and digital-twin–enabled pathways for deployment [17,18,33]. Within dentistry, real-time monitoring with automated model selection demonstrates feasibility for classifying equipment states from sensor streams such as temperature, vibration and pressure, with interpretable feature attribution suitable for clinic rollout20. Decision-analytic pipelines that integrate fault-tree analysis with fuzzy AHP and translate expert judgements into Bayesian networks quantify stage-specific failure probabilities and identify high-risk components under resource constraints, with documented cost reductions after implementation21. Complementary approaches emphasise information-fusion quality systems and big-data maintenance platforms to strengthen pre-, intra- and post-event control, mine failure distributions and guide preventive plans at scale22,23. Risk-based scheduling tools and prioritisation indices further operationalise maintenance by combining equipment criticality, calibration needs, age, location and hazards into transparent rules for service frequency24,26. Finally, international standards and guidance—covering dental units and chairs, medical-electrical safety and device risk management—provide the regulatory scaffolding within which reliability efforts must operate27,28.

Despite prior work on individual aspects—such as microbial control, fault classification, utilisation, or staffing—there is a paucity of integrative studies that triangulate failure logs, technical maintenance records, and clinic workload within university environments, where chairs are shared across departments and demand varies with teaching cycles. This study addresses that gap by linking chair-level failure reports with weekly usage logs and case mix across university clinics. By relating workload intensity and treatment specialisation to observed faults and repair actions, the analysis identifies operational risk factors and informs predictive maintenance strategies tailored to academic dental services. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to integrate failure records, workload logs, and predictive analytics to characterize dental chair reliability in a university environment. The analytical workflow combined maintenance tickets, equipment inventory data, and weekly chair usage (cases per week) across clinics and semesters, with faults harmonised into 16 standardized categories covering mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, and control-system issues for trend analysis and predictive modeling. The overall study workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results

A total of 1,853 dental chair failures were recorded and classified across six clinical specializations (see Table 1 in Methods). These specializations reflect combinations commonly encountered in university dental clinics, where chairs and units are shared across departments based on curricular demands. Figure 2A illustrates the overall failure burden per specialization. Rem&FixPros exhibited the highest number of failures (n = 424), followed by End&FixPros (n = 378) and ResDen&FixPros (n = 290), whereas Mixed and Pediatric specializations reported fewer faults. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant interaction effects between specialization and failure category on the number of failures (p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons confirmed that failure distributions significantly differed between high- and low-volume specialties, particularly for categories involving SE systems, control buttons, and delivery controls. Failure distributions were further examined through a heatmap (Fig. 2B), which displayed categorical counts across all specializations. The most frequent failure categories were SE malfunctions, delivery system issues, control switch failures, and power supply disruptions. For instance, Rem&FixPros and End&FixPros reported disproportionately high failures in SE (n = 51 and n = 27, respectively) and delivery controls (n = 52 and n = 22), while OralSurg&FixPros showed a marked concentration in support cushion and movement system failures. Notably, handpiece-related faults and general mechanical malfunctions were prevalent across all specializations but most prominent in Endodontics and Restorative Dentistry.

Overview of dental chair failures by academic year, clinical specialization, and fault category, including Pareto analysis of the most frequent failure types. (A) Total failures across specializations, with black lines between bars indicating significant differences after post-hoc analysis of the two-way ANOVA interaction between specialization, categories, and failures. (B) Heatmap showing failure counts by category (columns) and specialization (rows), highlighting trends in failure distribution. (C) Pareto analysis for each specialization, illustrating cumulative contributions of failure types to the total, with the red dashed line indicating the cumulative Pareto ratio.

Figure 2C provides a Pareto analysis of failure types within each specialization. The cumulative distribution curves highlight that a relatively small number of categories contributed to a large proportion of the total failures. In Rem&FixPros, for example, five categories (SE, delivery system, support cushion, control button, and handpiece) accounted for over 70% of total faults. Similar patterns were observed across other specializations, though the dominant categories varied slightly. This reinforces the principle that maintenance interventions targeting a limited number of high-frequency failure types may substantially improve operational performance. Taken together, these findings demonstrate clear differences in failure profiles across clinical specialties, both in volume and type. They also reveal actionable patterns suitable for targeted predictive maintenance, with SE, control units, and delivery system components representing key areas of vulnerability.

Figure 3 presents an analysis of the relationship between dental chair operating life and failure dynamics across categorized malfunction types. As shown in Fig. 3A, the average number of failures followed a nonlinear trend over the operating lifespan of the dental chairs. Failure frequency increased from the 2–4 year mark to peak at approximately six years of operation, before showing a gradual decline in units operating beyond ten years. This pattern may reflect both the aging of mechanical components and potential replacement of more severely deteriorated systems after prolonged use.

Trends and correlations between operating lifespan and annual failure rates of dental chairs based on aggregated data. (A) Trend of average failures across the operating life of dental chairs. (B) Correlation coefficients between operating life (years) and failure counts for component categories; asterisks indicate statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 3B details the correlation coefficients between operating life and specific failure categories. The correlation strengths were generally weak to moderate, but several trends are noteworthy. Positive correlations were observed between operating life and failures related to SE systems, surgical and weak saliva sections, and light units, suggesting that these components are more prone to wear with extended use. In contrast, categories such as control boards, crash sections, and general mechanical malfunctions showed weak negative correlations with operating life, possibly indicating failures that manifest early in the equipment lifecycle due to design limitations or handling stress. Notably, cuspidor-related faults exhibited the strongest negative correlation (r ≈ −0.13), suggesting a greater likelihood of malfunction in newer units, which may be attributed to structural design sensitivity or installation inconsistencies.

Weekly dental chair usage demonstrated marked variability across different case types, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. Fixed prosthodontics exhibited the highest average utilization (261.2 ± 84.6 cases/week), followed closely by removable dental prosthesis (241.9 ± 78.1 cases/week) and restorative dentistry (232.5 ± 60.7 cases/week). In contrast, pediatric and periodontal cases displayed substantially lower averages of 112.4 ± 38.9 and 118.1 ± 36.2 cases/week, respectively. The standard deviation bands were widest in prosthodontic disciplines, suggesting more erratic weekly scheduling or peak clustering over the semester.

Statistical comparison of case-type-specific usage confirmed significant differences in chair load across disciplines. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of case type on weekly chair usage (F(6, 273) = 12.81, p < 0.001). As shown in Fig. 4B, boxplots highlighted the distribution of chair usage, with several workload outliers observed in oral surgery with fixed prosthodontics, peaking above 645 weekly chair uses. Tukey HSD post-hoc tests indicated that restorative, fixed, and removable prosthodontic treatments involved significantly higher usage than periodontal or pediatric treatments (all p < 0.01).

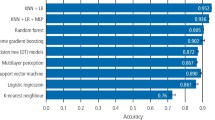

Predictive modelling of weekly workload based on case type and calendar week yielded limited predictive accuracy. The Random Forest achieved R² = 0.16 and RMSE = 68.2, marginally better than linear regression (R² = 0.15; RMSE = 70.7) as shown in Fig. 4C. Feature-importance profiles from the Random Forest indicated that case-mix variables dominated temporal markers: removable prosthodontics, paediatric dentistry and fixed prosthodontics (Fig. 4D) had the highest permutation scores (0.231, 0.172 and 0.149, respectively), whereas week number contributed relatively little (0.058). These results imply that fluctuations in service composition carry more signal for chair demand than the academic calendar alone, and that substantial variance remains attributable to unobserved constraints such as staffing, cancellations, examination blocks and short-notice schedule changes.

Analysis of weekly chair usage patterns and predictive modelling in dental clinics. (A) Weekly chair usage (cases per week) across academic semesters per case type with mean trend lines and standard deviation shading. (B) Boxplot of total weekly chair usage distributed by case type. (C) Actual versus predicted weekly chair usage using RF and Linear Regression models based on case type and week number. (D) Feature importance scores from the RF model where feature importance was calculated based on the increase in out-of-bag prediction error after permuting each predictor variable.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive investigation into the interplay between dental chair workload, failure typologies, operating life, and predictive modeling potential in a university-based dental care environment. By integrating clinical scheduling data with failure logs across multiple specializations, the analysis reveals critical insights into how clinical demands shape equipment reliability and how data-driven tools can inform proactive maintenance.

The observed variation in chair usage across dental case types underscores the heterogeneous nature of resource demand in teaching clinics. Fixed and removable prosthodontics, alongside restorative dentistry, consistently accounted for the highest weekly chair occupancy, reflecting their procedural complexity and time intensity. These findings are in line with operational workload trends reported in studies on private and public dental systems, where prosthodontic services are correlated with extended chair time and frequent equipment cycling12,13. Conversely, disciplines such as pediatric and periodontal care demonstrated lower and more uniform workloads, which may reflect both shorter appointment durations and more stable scheduling.

Significant differences in usage were matched by disproportionate failure rates in key dental chairs. SE units, delivery systems, and control panels emerged as dominant failure points across high-usage clinics, suggesting a direct association between usage intensity and mechanical degradation. This finding corroborates previous technical audits of dental units which identified high-frequency components as key maintenance vulnerabilities5,6,7. The heatmap and Pareto analyses further clarified that a small subset of failure types accounts for a majority of incidents within each specialization, highlighting opportunities for targeted maintenance protocols. Such category-focused interventions align with quality improvement frameworks previously validated for dental unit waterlines and infection control systems3,4.

An additional dimension explored was the impact of operating life on failure rates. Interestingly, failure incidence peaked around six years of chair operation, declining slightly in older units. This non-linear pattern may reflect institutional replacement policies, component upgrades, or a “burn-in” period where initial design limitations manifest. Specific failure categories, such as cuspidor and mechanical frame malfunctions, showed negative correlations with age, implying vulnerabilities in newer units—possibly due to newer designs or improper initial assembly—whereas components like SE and lighting systems exhibited wear-related degradation over time. These temporal findings extend prior reports on medical equipment lifecycles14 by offering category-specific trajectories useful for scheduling preventive inspections.

The low \(\:{R}^{2}\) (0.16) observed for workload prediction is interpreted as an expected consequence of modelling with administrative features that only partially capture real-world drivers of weekly demand. Chair utilisation in academic clinics is influenced by latent and rapidly varying factors—including staffed-chair hours, emergency bookings, student assessment cycles, supply interruptions and ad hoc closures—that are not represented in the current feature set. Aggregation at weekly granularity further attenuates signal by blending peaks and troughs within weeks. Under these conditions, limited predictive accuracy should be viewed as an exploratory baseline rather than a deployable forecaster. The exercise nonetheless provides decision-relevant insight: case mix consistently outperformed calendar variables, supporting maintenance planning that is keyed to service composition rather than to fixed temporal intervals. Future gains are most likely to come from integrating higher-frequency and chair-level covariates (for example, operational hours per chair, cancellation logs, sensor-derived usage proxies and consumable stock events), expanding across semesters to mitigate concept drift, and evaluating time-series models with calendar and event exogenous regressors. Complete correlation coefficients and adjusted p-values are reported to avoid superficial interpretation of wear effects; the small effect sizes underscore the need for multivariate approaches when prioritising maintenance actions.

Taken together, the results support a transition from reactive, failure-based dental unit maintenance toward proactive, usage-informed service models. Specialization-specific patterns of strain and failure suggest that uniform maintenance schedules may be suboptimal in academic clinics. Tailored protocols based on usage history and failure concentration may improve equipment longevity, reduce downtime, and ultimately enhance clinical efficiency30. Moreover, such approaches align with broader safety initiatives in dentistry that call for system-level responses to predictable sources of equipment-related disruption2,11.

Limitations

Although structural zeros in the dataset reflect true absence of failures, the resulting sparsity (particularly in rare failure types) may have limited correlation strength and reduced predictive model performance. Future work should incorporate larger multisite datasets with richer event diversity to overcome this constraint. This analysis is monocentric, reflecting workflows, training mix and scheduling practices at a single university. External validity may therefore be constrained, particularly for institutions with different staffing models, appointment policies or academic calendars. The equipment fleet was relatively homogeneous, with a large proportion of units labelled as “Chinese,” which may proxy for overlapping vendors, components and quality tiers. Such homogeneity can attenuate apparent between-brand differences and limit inference to chair designs that share similar hydraulic, pneumatic and control architectures; results should be generalised cautiously to premium or markedly different platforms. The retrospective failure dataset contained incomplete fields for several component groups, with missingness distributed unevenly across G1–G16; under-reporting in sparsely documented categories could bias category totals and dilute correlations. Although a structured codebook and inter-rater procedures were employed for failure taxonomy assignment, residual misclassification cannot be excluded. Aggregation at the clinic-week level, together with non-stationary demand across semesters, may further attenuate effect sizes. Finally, the predictive models were built from administrative features (case mix and calendar markers) and consistent with this limited feature set, yielded low explanatory power; the reported \(\:{R}^{2}\) should be interpreted as an exploratory baseline rather than a deployable forecaster.

Methods

Data collection

Setting, design and ethics

This retrospective study was conducted at the Faculty of Dentistry, Al-Andalus University for Medical Sciences, Tartous, Syria, and approved by the university’s Ethics Committee (approval No. 57 − 15/02/2024). All methods followed relevant guidelines and regulations. No human participants or tissues were involved; only anonymised, aggregated technical and operational records were analysed. Owing to the retrospective design, informed consent was waived. Data covered two consecutive academic years (2022–2024) across ten clinics spanning six clinical specialisations (Table 1). The dataset is available as supplementary material.

Data sources and linkage

Failure information was compiled from service tickets and maintenance forms completed by clinic technicians and curated by the Biomedical Engineering Unit; records were digitised and exported to comma-separated values format for analysis. Operational data comprising weekly clinic activity (operational days, patient counts, and case-type distributions) were abstracted from scheduling sheets maintained by clinic coordinators and reconciled against the central register before export. Failure and usage records were linked deterministically by clinic code and calendar week. All direct identifiers were removed at source; study codes were assigned prior to analysis.

Failure taxonomy and validation

Free-text fault descriptions (more than 80 unique terms) were harmonised into 16 mutually exclusive categories (G1–G16) covering motor and compressor faults, control-circuit malfunctions, hydraulic leaks, saliva-ejector blockages, delivery-unit faults, lamp/power issues and water-pressure defects, among others. The taxonomy was derived from manufacturer service manuals, local standard operating procedures and historical ticket language, and formalised in a codebook with inclusion/exclusion rules and examples. A pilot recoding of a random sample was used to refine category boundaries, after which the 16-group scheme was fixed for full-dataset coding. To assess labelling reliability, two biomedical-engineering raters independently coded a stratified random subset; agreement was evaluated using Cohen’s κ with 95% confidence intervals and percentage agreement, and disagreements were resolved by consensus with adjudication by a senior engineer. Adequacy was pre-specified as κ ≥ 0.70; final κ estimates and confidence intervals are reported alongside the results and in the Supplementary Information.

Variables and definitions

Outcomes were failure incidence per clinic-week and per chair-semester, the distribution of failure categories (G1–G16) by specialisation, and operating life (years in service). Exposures and covariates included weekly workload (patient counts and operational days), case mix (proportions of case types per week), specialisation, and temporal markers (academic week, semester and year). Records lacking a clinic code, week or resolvable category after adjudication were excluded. Weeks with scheduled closures (for example, holidays) were retained with operational days set to zero.

Data handling and processing

Duplicate tickets were collapsed by identifier and date; free-text fields were normalised by lower-casing, spelling correction and synonym mapping defined in the codebook. Failures were aggregated to the clinic-week level and aligned to weekly usage. Missing usage values judged to be missing at random were imputed by linear interpolation across adjacent weeks, with sensitivity analyses repeating all primary models after excluding imputed weeks. Extreme-usage weeks above the 99th percentile were inspected and flagged; analyses were repeated with and without these weeks to assess robustness.

The raw dataset contained multiple sheets, with weekly usage logs and categorized failures (G1–G16) at the clinic level. Empty cells in these sheets reflected weeks or components with no failures recorded rather than missing data. For preprocessing, empty records values were systematically replaced with zeros in MATLAB to standardize non-event reporting. Failure counts were then aggregated by category and specialization to generate analyzable matrices. This ensured consistent interpretation of blank entries as ‘no fault recorded’ rather than unavailable data, thereby avoiding data loss or artificial inflation of missingness during statistical modeling.

Data analysis

Correlation analysis

Relationships between extended clinical features (operating life, average daily usage, operational days per week) and grouped failure categories (G1–G16) were examined using Pearson product–moment correlations to capture linear associations. Each failure group was defined as the sum of its constituent subcomponent columns. Correlation structure was visualised as a matrix heatmap with accompanying coefficient plots. Given non-normality of some counts, Spearman’s ρ was calculated in sensitivity analyses; conclusions regarding direction and magnitude were concordant. Operating life (years) showed weak but discernible positive correlations with several G groups, consistent with gradual wear accumulation in specific subsystems.

Unsupervised clustering

hair-level failure profiles were segmented using k-means clustering with k = 3. Features comprised total failures per G group concatenated with operating life. All variables were standardised (z-scores) to balance the contribution of counts and lifespan; square-root transformation was applied to highly skewed counts in a sensitivity run. The choice of k was supported by the elbow criterion and average silhouette widths. Clusters were visualised using three-dimensional scatter plots (principal-component projection) and centroid heatmaps. The solution separated high-failure/short-lifespan chairs from low-failure/long-lifespan units, delineating profiles potentially actionable for staggered maintenance or early replacement.

Pareto failure analysis by specialization

For each of the six clinical specialisations, failure frequencies were aggregated by G category, ranked and plotted with cumulative contribution curves. Across specialisations, approximately 70% of failures were attributable to five categories, identifying a “vital few” amenable to targeted intervention (for example, stocking of critical spares, focused technician training and pre-emptive inspection routines).

Operating life vs. failure trends

Mean total failures were computed for each unique year of operating life, and trend lines were fitted using locally weighted regression to mitigate year-to-year noise. Failure burden generally increased with age, with plateauing beyond approximately five years in some clinics, suggesting diminishing returns from uniform servicing schedules and supporting proactive replacement or intensified inspection in mid-life windows.

Inferential statistics

The effects of specialisation and G category on failure counts were tested using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with interaction. Assumptions were examined by inspecting residuals; where heteroscedasticity was present, square-root transformation and heteroscedasticity-robust (HC3) standard errors were applied. Main effects for both factors and their interaction were statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the influence of component category on failure rates depends on clinical context.

Usage pattern modeling

Weekly usage was modelled as a function of case type and calendar position. Case types were one-hot encoded; features included specialisation, academic week and semester, and operational days. Models comprised random forest (RF) regression and ordinary least squares, referencing prior applications of predictive maintenance and analytics in clinical engineering29,30,31. Hyperparameters for RF (number of trees, maximum depth, minimum samples per leaf and features) and regularised linear models (penalty and λ) were tuned by grid search within the inner loop. Performance metrics were the coefficient of determination and root-mean-square error (RMSE), averaged across outer folds as mean ± standard deviation.; point estimates from a single 80/20 split are reported only for comparability with previous baselines. Robustness was assessed by repeating the analysis after excluding extreme-usage weeks and by replacing raw weekly counts with per-day averages; conclusions were unchanged. Training and evaluation followed the nested cross-validation protocol described above; folds respected clinic identity and semester boundaries. Performance was summarised using the coefficient of determination and RMSE, defined as:

where \(\:{y}_{i}\:\)denotes observed weekly counts, \(\hat{y}_{i}\) predictions, \(\bar y\) the sample mean and n the number of observations. Feature contributions were examined using permutation importance for all models, complemented by SHAP summaries for the RF. Case-mix features consistently dominated temporal markers, aligning with the descriptive finding that workload intensity and clinical specialisation are primary determinants of chair demand.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available as supplementary material.

References

Ni, L. et al. Research progress on microbial contamination and infection prevention and control in the waterways of hospital dental units. Chin. J. Hosp. Infect. 28, 5 (2018).

Siriwatana, K. & Pongpanich, S. A 5-year retrospective analysis of adverse events in dentistry at the dental Hospital, faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn university. BMC Oral Health. 24, 1294 (2024).

Fujita, M., Mashima, I. & Nakazawa, F. Monitoring the decontamination efficacy of the novel Poseidon-S disinfectant system in dental unit water lines. Journal Microbiol. Immunol. Infection 50, 270–276 (2017).

Umer, F., Khan, F. R. & Tejani, K. Managing dental unit waterlines: a quality improvement programme. BMJ Open. Qual. 11, 284–292 (2022).

Lu, Z. Common faults and analysis of Taurus dental unit. Med. Equip. 41, (2020).

Jin, J., Liu, H. & Chu, Y. Analysis and solution of dental unit failure. Glob.Clin. Eng. J. 4, 50–57 (2015).

Huang, G. et al. Collective malfunctions and maintenance of dental units in dentistry. Med. Equip. 35, 117–118 (2022).

Tošić, G. Importance of maintenance of light units for polymerization of composites in restorative dentistry. Stomatološki Glasnik Srbije. 51, 142–145 (2004).

Liu, Y. The use and maintenance of dental handpieces. China Med. Equip. 28, 109–110 (2013).

Niu, Y., Lu, Q. & Li, X. The current situation and causes of water pollution in dental units. Chin. J. Infect. Control. 17, 843–847 (2018).

Alhussaini, K. et al. Evaluation of medical equipment maintenance and skilled manpower requirement among private dental centres in Riyadh, Saudi arabia: a pilot study. Technol. Health Care. 32, 2409–2419 (2024).

Alsalleeh, F. et al. Analyzing private dental clinics in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 30, 70–73 (2018).

Atkin, P. A., Khan, A. & Simms, M. L. Chairside learning on undergraduate clinics: general dental and human disease themes. Br. Dent. J. 237, 212–216 (2024).

Wang, B. Medical equipment maintenance: management and oversight. Synthesis Lectures Biomedical Eng. 7, 1–85 (2012).

Al Johara, A. Factors affecting utilization of dental health services and satisfaction among adolescent females in Riyadh City. Saudi Dent. J. 22, 19–25 (2010).

Al-Hassan, M. & AlQahtani, S. Preparedness of dental clinics for medical emergencies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 31, 115–121 (2019).

Boppana, V. R., Yang, M., Li, F. & Qiu, W. Data analytics for predictive maintenance in healthcare equipment. and Integrating AutoGluon for real-time monitoring and classification of dental equipment performance. IEEE Access (2024). (2023).

Li, K., Su, L., Cheng, J., Sun, Y. & Ma, X. Improving maintenance efficiency and controlling costs in healthcare institutions through advanced analytical method. Sci. Rep. 15, 18377 (2025).

Li, J., Mao, Y. & Zhang, J. Maintenance and quality control of medical equipment based on information fusion technology. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 9333328 (2022).

Li, J., Mao, Y. & Zhang, J. Construction of medical equipment maintenance network management platform based on big data. Front. Phys. 11, 1105906 (2023).

Hernández-López, L. A. & Pimentel-Aguilar, A. B. Ortiz-Posadas, M. R. An index to prioritise the preventive maintenance of medical equipment. Health Technol. 10, 399–403 (2020).

Vala, S., Chemweno, P., Pintelon, L. & Muchiri, P. A risk-based maintenance approach for critical care medical devices: a case study application for a large hospital in a developing country. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manage. 9, 1217–1233 (2018).

Zamzam, A. H. et al. A systematic review of medical equipment reliability assessment in improving the quality of healthcare services. Front. Public. Health. 9, 753951 (2021).

Lei, Y. et al. Machinery health prognostics: a systematic review from data acquisition to RUL prediction. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 104, 799–834 (2018).

ISO. ISO 14971:2019 — Medical Devices: Application of Risk Management To Medical Devices (International Organization for Standardization, 2019).

WHO. Medical Equipment Maintenance Programme Overview (World Health Organization, 2011).

IEC. IEC 80601-2-60:2019 — Medical Electrical Equipment — Part 2–60: Particular Requirements for the Basic Safety and Essential Performance of Dental Equipment (International Electrotechnical Commission, 2019).

ISO. ISO 7494-1:2018 — Dentistry: Stationary Dental Units and Dental Patient chairs — Part 1: General Requirements (International Organization for Standardization, 2018).

Borup, D., Christensen, B. J., Mühlbach, N. S. & Nielsen, M. S. Targeting predictors in random forest regression. Int. J. Forecast. 39, 841–868 (2023).

Moradzadeh, A., Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B., Abapour, M., Anvari-Moghaddam, A. & Roy, S. S. Heating and cooling loads forecasting for residential buildings based on hybrid machine learning applications: a comprehensive review and comparative analysis. IEEE Access. 10, 2196–2215 (2021).

Doz, D., Cotič, M. & Felda, D. Random forest regression in predicting students’ achievements and fuzzy grades. Mathematics 11, 4129 (2023).

Malik, Z., McBride, K. A., Williams, K., Cockrell, D. & Collins, C. E. Dental team barriers and enablers for the dental management of adults with severe obesity: a qualitative analysis. BDJ Open. 10, 83 (2024).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. wrote the first draft and collected and analyzed data. E.I. contributed to the first draft, data analysis reviewing, editing, and finalizing the manuscript. A.K. provided reviewing, editing, and supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical committee at Al-Andalus University for Medical Sciences, Tartous, Syria, approved the study under session number 18, with the assigned ID number 57 − 15/02/2024. The study did not involve direct interaction with human participants or the use of human tissue. Only anonymized, aggregated technical data regarding dental chair failures and usage patterns were analyzed. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Al-Andalus University for Medical Sciences waived the need of obtaining informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Massoud, S., Ismaiel, E. & Al Kayal, A. Retrospective analysis of dental chair failures and usage patterns in academic dental clinics. Sci Rep 15, 42065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26173-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26173-z