Abstract

With rapid urbanization exacerbating stormwater pollution and stressing limited water resources, developing efficient and cost-effective treatment technologies to transform contaminated urban runoff into a usable water source has become a pressing environmental challenge. This research investigated the effectiveness of a porous concrete matrix containing dolomite adsorbent for treating urban stormwater runoff. Incorporation of dolomite adsorbent into the porous concrete matrix resulted in a 20% decrease in hydraulic conductivity and a 54.78% reduction in porosity were observed. Conversely, compressive strength increased by 34.85%, and tensile strength improved by 21.56%. To optimize removal of chemical oxygen demand (COD), total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), and lead ions (Total Pb), the study employed a combined approach of response surface methodology utilizing a Box-Behnken design (RSM-BBD) and a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model as a function of six operational parameters: 63 < COD < 146 mg L-1, 320 < TDS < 1600 mg L-1, 66 < TSS < 937 mg L-1, 2 < LTotal Pb < 5 mg L-1, 15 < contact time < 360 min, and 5 < dolomite levels < 15%. The RSM-BBD approach outperformed the GEE model, demonstrating its ability to effectively capture non-linear relationships between input variables and removal efficiencies. The sensitivity analysis, based on Wald Chi-square values, showed that the removal of TDS, COD, TSS, and total Pb was primarily influenced by the initial concentrations of TDS, TDS, TSS, and the dolomite adsorbent dosage, respectively. The system achieved complete removal (100%) of Total Pb, along with substantial reductions of 83% for TSS, 78.91% for COD, and 64.68% for TDS. These remarkable removal efficiencies indicate the potential of the porous concrete-dolomite adsorbent system for treating urban stormwater runoff.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban stormwater runoff harvesting presents a promising alternative approach to meet the growing demand for urban water supply, driven by urbanization, population growth, rising living standards, and climate changes1,2,3. Nevertheless, urban stormwater runoff as a nonpoint source of pollution contributes dramatically to deterioration of surface water quality4. The quantity and quality of urban stormwater runoff can be affected by land use, traffic intensity, rainfall intensity, and climate. However, contamination of water resources from nonpoint sources pollution has not been well documented and is difficult to manage and control5. Heavy metals, nutrients, hydrocarbons, sediments, pesticides, and pathogens are the main contaminants in the urban stormwater runoff6. Among the heavy metals found in urban stormwater runoff, Total Pb is a prevalent and persistent toxic metal that originates from various sources, such as automotive emissions, deteriorating lead-based paints, and industrial activities7,8,9. As a regulated contaminant with strict permissible limits in water bodies due to its toxic effects, the removal of Total Pb from urban runoff is a regulatory priority. Therefore, Total Pb was selected as a representative heavy metal pollutant due to its significance as an urban stormwater contaminant, its well-established adsorption capability, and its regulatory importance. In this respect, some practices such as constructed wetlands, retention basins, and rain gardens are limited in their ability to control the quantity of water4. So, it is necessary to elaborate on new, more economical methods to enhance the treatment of pollutants in stormwater runoff.

Several physical processes consisting of screening, flotation, settling, and filtration are commonly employed as a municipal wastewater pre-treatment stage for solid–liquid separation10. Most of these processes are combined with other technologies such as physical, chemical, and biological systems for municipal wastewater treatment11,12,13,14,15,16, and are followed by a disinfection stage as post-treatment. However, the effluent qualities obtained from typical wastewater treatment plants often do not meet the non-potable reuse standards in terms of the COD, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), TSS, TDS, and pH17.

Application of porous concrete has lately garnered significant attention for use in airports, patios, parking lots, areas with heavy rainfall, low-traffic urban road systems, and hydraulic structures. This is due to its ability to increase the quality and decrease the quantity of urban stormwater runoff18. Porous concrete is composed of Portland cement, coarse aggregate, with or without fine grains, additives, and water19. The porosity, permeability coefficient, and compressive strength of porous concrete can range from 11–35%, 1.4–12.3 mm s-1, and 3.5–28 Mpa, respectively19. Abedi-Koupai et al.9 found that porous concrete containing iron slag with a sand filter can achieve 43% removal of COD, 95% removal of Total Pb, 91% removal of turbidity and 70% removal of TSS. Teymouri et al.10 assessed the performance of porous concrete containing mineral adsorbents (zeolite, pumice, perlite, and LECA) for municipal wastewater pretreatment. They reported reductions of approximately 30.5% for COD, 48% for BOD, and 40% for TSS. Among the mineral adsorbents, zeolite had the best performance in improving municipal wastewater quality. Javaheri-Tehrani et al.20 concluded that the combination of porous concrete and phytoremediation could be an economically cost-effective technique for reducing pollution in domestic wastewater effluent and urban runoff. Teymouri et al.21 demonstrated that pervious concrete containing 15% iron slag effectively reduces urban runoff contaminants, achieving reductions of 69.75%, 68%, and 69% in COD, TSS, and turbidity, respectively. Teymouri et al.22 demonstrated that replacing coarse aggregate with iron slag in pervious concrete significantly enhanced compressive strength, peaking at 16.80 MPa with a 75% replacement rate. In contrast, zeolite replacement reduced strength, reaching a minimum of 9.40 MPa at full (100%) substitution. Despite these differences, both iron slag- and zeolite-based pervious concrete exhibited potential for wastewater post-treatment applications, offering a balance between mechanical performance and permeability. Liang et al.23 demonstrated that porous concrete modified with nanometer titanium dioxide (nTiO2) effectively removed stormwater pollutants, achieving purification efficiencies of 60% to 90% for methylene blue, ammonia nitrogen, and total phosphorus.

The incorporation of mineral materials into porous concrete has gained widespread attention for reducing production costs, enhancing compressive strength, and improving treatment performance10. Dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), a low-cost and globally abundant magnesium-limestone, is a promising candidate due to its unique properties. Its crystalline structure—composed of alternating calcium and magnesium carbonate layers—imparts low solubility, high hardness, and abrasion resistance, making it valuable in agriculture (as a soil conditioner), industry (as a MgO source and steel flux), and wastewater treatment (as an adsorbent)24,25. When integrated into porous concrete, dolomite exhibits strong affinity for Total Pb removal via ion exchange and precipitation mechanisms26,27.

To optimize experimental efficiency, response surface methodology (RSM) with Box-Behnken design (BBD) is widely employed for investigating and optimizing pollutant removal processes. This statistical approach uses second-order polynomial equations to model relationships between variables and responses, reducing experimental runs while maintaining accuracy28,29,30,31,32. For analyzing dependent observations in repeated-measures data, generalized estimating equations (GEE) offer robust estimators that outperform traditional fixed/random effects models33,34.

While prior research has validated porous concrete modified with conventional adsorbents (e.g., iron slag, zeolite), this study introduces a transformative approach to urban stormwater treatment through three key innovations: (1) development of a novel porous concrete-dolomite adsorbent system, leveraging dolomite’s cost-effectiveness and high efficiency; (2) the application of advanced predictive modeling to optimize pollutant removal; and (3) implementation of a recirculating column system that simulates real-world dynamic flow conditions. Together, these innovations not only deepen the scientific understanding of adsorption mechanisms in porous concrete but also significantly improve its practical viability for urban runoff treatment, particularly in water-scarce regions where efficient and sustainable solutions are critical.

Hence, the main goal of this study is to examine the capability of porous concrete containing dolomite adsorbent to reduce urban stormwater runoff pollution. Moreover, the specific goals are as follows: (1) investigate the mechanical and physical properties of constructed porous concrete such as compressive strength, tensile strength, porosity, and permeability coefficient; (2) study and optimize the interactive effects of qualitative parameters such as COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb to maximize pollutant removal from urban stormwater runoff using RSM-BBD; (3) construct a second-order polynomial model based on the RSM-BBD results, statistically validated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and lack-of-fit analysis, to predict pollutants removal; (4) compare the performance of RSM-BBD and GEE models by employing statistical criteria in stormwater runoff quality prediction; (5) evaluate the quality standards of treated urban stormwater runoff for application in groundwater recharge and landscape irrigation.

Materials and methods

Mixture design

Porous concrete was created using a mixture of Portland cement type 2, water, coarse aggregates, and fine aggregates, following the guidelines of ACI 211.3R codes (Fig. S1). Additionally, three proportions (5%, 10%, and 15%) of dolomite adsorbent with particle sizes ranging from 10 to 120 μm (Fig. S1), provided by Madankavan Co. Tehran, Iran, were incorporated into the mixture. The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of these materials is presented in Table 1. Five standard aggregate gradations, #89, #78, #67, #12.5, and #9.5, were selected according to ASTM C-33. The selected grading numbers and the weight percentage passing through each sieve are presented in Table S1. The mix design was prepared considering a mixture density of 1930 kg m-3, a water/cement (w/c) ratio of 0.29, a cement content of 325 kg m-3, and an aggregate of 1480 kg m-3. Table 2 presents the details of the mix designfor different treatments, with a concrete volume having a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 15 cm.

Mechanical and physical properties of porous concrete

Compressive and tensile strengths

Compressive and tensile strengths of cubic porous concrete samples (150 × 150 × 150 mm) were tested over a curing period of 60 days according to ASTM C109 and ASTM C496, respectively35.

Porosity

Cubic porous concrete samples (150 × 150 × 150 mm) were tested for porosity according to ASTM C1754 standard36. First, the samples were placed in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h to dry and then weighed. Next, the dried samples were submerged in a water container for 30 min to measure buoyant weight using an Archimedes scale through the following equation:

where \(\;n\) is porosity (%), \(\;W_{1} \;(g)\) and \(\;W_{2} \;(g)\) are submerged and oven-dried weights, respectively, \(\rho_{W}\) is water density \((g\;cm^{ - 3} )\) and \(V\) is total volume of the sample \((cm^{3} )\).

Hydraulic conductivity

A falling-head method was employed to measure the permeability coefficient of cubic porous concrete samples (150 × 150 × 150 mm) using the following equation37:

where \(\;K\) is the hydraulic conductivity \((mm\;s^{ - 1} )\), \(\;a\) \((mm^{2} )\) and \(A\) \((mm^{2} )\) are the cross-section area of the inlet water tube and porous concrete samples, respectively, \(h_{1}\) \((mm)\) and \(h_{2}\) \((mm)\) are the initial and final heights of the water column, respectively, \(L\) is the length of the sample \((mm)\) and \(t\) is the time for the transition of water from \(h_{1}\) to \(h_{2}\) (sec).

Experimental set-up

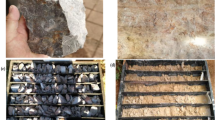

The experiments were conducted in the Water Engineering Department laboratory at Fasa University, Iran, located in the semi-arid region of Fars Province. This region receives an average annual precipitation of 290 mm, primarily during intense winter storms that generate rapid runoff and exacerbate water management challenges. To address these conditions, we developed a laboratory-scale system to evaluate dolomite-modified porous concrete for stormwater treatment. To conduct the experiments, cylindrical columns were constructed using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 70 cm. Each column was equipped with a drainage valve at the bottom. To form the mold for the porous concrete, smooth-surfaced foam inserts, shaped as nearly truncated cones (10 cm in diameter and 15 cm in height), were placed inside each column at a height of 15 cm from the bottom. Concrete containing 5–15% dolomite adsorbent was then poured into the columns over the foam molds, filling them to a height of 15 cm. After 24 h, the concrete specimens were washed, and the foam molds were carefully removed. The columns, now containing partially cured concrete, were placed in a water curing pond for 7 days. Following the curing period, the columns were removed from the pond, and a 15 cm sand filter layer was added to the bottom of each column to facilitate drainage and serve a foundation for the porous concrete. Finally, the ends of each column were sealed with PVC caps, and the columns were placed on a steel foundation (Fig. 1). The experimental testing protocol implemented a sophisticated simulation system designed to replicate intense precipitation events characteristic of Fasa’s regional climate patterns. The system employed a closed-loop configuration operating at a sustained rainfall intensity of 16 mm h-1 over a 6-h duration, enabling comprehensive evaluation of the treatment system’s long-term performance capabilities. The synthetic stormwater formulation incorporated precisely controlled concentrations of key urban runoff pollutants, including COD ranging from 63 to 146 mg L-1, TDS spanning 320 to 1600 mg L-1, TSS varying between 66 and 937 mg L-1, and lead (total Pb) concentrations from 2 to 5 mg L-1. This carefully calibrated solution was circulated through a dolomite-modified porous concrete matrix utilizing a peristaltic pump system, maintaining a consistent hydraulic loading rate of 153 L m-2 h-1 (equivalent to 20 mL min-1). The treatment process employed a downward flow configuration, with the urban runoff solution percolating through the treatment column under controlled conditions. Treated effluent was systematically collected via the drainage valve and reintroduced to the feed tank, establishing continuous contact between pollutants and the adsorbent media. This dynamic recirculation approach maintained stable operational parameters throughout the 360-min experimental duration. To evaluate treatment efficiency and system performance, samples were systematically collected at predetermined intervals.

Experimental set-up for this study: (a) smooth surface foams with an almost truncated cone shape; (b) placement of foams into each column; (c) closing the ends of each column; (d) lubricating the inner surfaces of cylindrical molds with oil; (e) pouring concrete into the columns over the foam; (f) arranging the columns with concrete in a curing water pond; (g) treating storm runoff with the proposed system; (h) setup of cylindrical columns.

Adsorption test

The porous concrete matrix was engineered with a fixed composition of pumice (38.27 g) across all treatments (A-D, Table 2), serving as a stable mineral framework. The active adsorbent component—natural dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2]—was systematically varied from 0% (control, Treatment A) to 5%, 10%, and 15% by weight (Treatments B-D respectively). This design enabled precise evaluation of dolomite’s dose-dependent effects while controlling for pumice’s constant mineral contribution. The dolomite’s chemical composition, characterized by XRF analysis (Table 1), revealed a predominance of CaO (65.12%) and MgO (34.36%), with particle sizes ranging between 10–120 μm. The adsorption tests employed a closed-loop recirculation system where test solutions were pumped downward through the porous concrete matrix at a controlled flow rate of 20 mL min-1 (equivalent to 153 L m-2 h-1 hydraulic loading rate) for a duration of 360 min. This testing period was strategically selected to simulate complete storm hydrographs while ensuring sufficient contact time for adsorption equilibrium to be established. The water quality assessment focused on four key parameters: COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb ion concentrations. For synthetic stormwater preparation, a four-liter solution was formulated by combining precise volumes containing target concentrations of each contaminant. The COD component was derived from a mixture of kitchen and shower wastewater to simulate realistic organic loads, while TSS was introduced through a controlled blend of silt and clay particles (2–8 μm). Ionic constituents were carefully regulated using sodium chloride (NaCl) for TDS and lead nitrate (Pb(NO3)2) for Total Pb ions. Analytical measurements employed specialized instrumentation: residual COD concentrations were determined using a Unico 2100 spectrophotometer, TDS was measured via conductivity using a Hanna EC-214 m, and TSS concentrations were established through gravimetric analysis following established protocols (Abedi-Koupai et al.9). Lead concentrations were measured as total lead using a Perkin-Elmer 3030 atomic absorption spectrophotometer following nitric acid digestion, which converts all lead species to detectable Pb2⁺ ions. Although initially reported as “Pb(II)” in the analyses, all values represent the total lead content, including both dissolved and particulate-bound fractions.

For further investigations, equilibrium adsorption characteristics were determined through comprehensive batch experiments evaluating the adsorption behavior of dolomite-modified porous concrete for urban stormwater treatment. The equilibrium data were analyzed using two well-established isotherm models, specifically the Langmuir and Freundlich models. The theoretical background and assumptions of these models are provided in the supplementary data. Synthetic stormwater solutions were prepared with contaminant concentrations representative of typical urban runoff conditions: COD (63–146 mg/L), TDS (320–1600 mg/L), TSS (66–937 mg/L), and total Pb (2–5 mg/L). These ranges were selected to encompass both baseline and peak pollution scenarios while maintaining alignment with the study’s optimization framework. Porous concrete specimens containing 15% dolomite (57.41 g dolomite per 325.3 g total mixture) were prepared to ensure experimental consistency. The material was crushed and sieved to obtain uniform particles (0.5–1 mm), providing standardized surface area for adsorption studies. Batch experiments employed 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing adsorbent doses of 10 g/L for TDS, COD, and TSS removal studies, while a lower dose of 1 g/L was used for Pb adsorption tests due to its higher affinity for dolomite. The adsorption studies maintained constant agitation at 120 rpm using a shaker incubator set at 25 °C, with a fixed contact time of 360 min—a duration established through preliminary kinetic studies as sufficient to reach adsorption equilibrium. The system pH remained at 7.0 throughout the experiments, reflecting typical stormwater conditions. Following the required equilibrium period, samples were filtered and analyzed using standardized analytical methods. The resulting equilibrium data were subsequently fitted to both Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models to quantify removal capacities across varying contaminant concentrations.

Real urban stormwater sample

To assess the system’s performance under realistic conditions, urban stormwater was sampled from impervious surfaces and overland flows in trafficked areas, parks, gardens, and construction sites in Fasa, Iran. Sampling was conducted during three separate storm events with sufficient intensity (more than 4 mm h-1) to mobilize contaminants. The varying characteristics of the collected stormwater (Table 3) resulted from differences in land use, antecedent dry periods, and rainfall characteristics across these events, providing a representative range of pollutant loadings for validation testing4.

Experimental design by RSM-BBD

The optimization of urban stormwater runoff treatment using porous concrete amended with dolomite adsorbent was conducted through RSM-BBD, employing a recirculating column filtration system to simulate real-world stormwater infiltration conditions. The study systematically evaluated six key operational parameters as independent variables: initial COD concentration (63–146 mg L-1), initial TDS concentration (320–1600 mg L-1), initial TSS concentration (66–937 mg L-1), initial Total Pb concentration (2–5 mg L-1), contact time (15–360 min), and dolomite content (5–15%). Pollutant removal efficiencies for COD, TDS, TSS, and total Pb served as the response outputs. All selected parameter ranges corresponded to typical urban stormwater samples. The experimental setup consisted of cylindrical PVC columns (10 cm diameter × 70 cm height) containing a 15 cm layer of dolomite-modified porous concrete over a 15 cm sand filter base, with a peristaltic pump maintaining constant hydraulic loading at 153 L m⁻2 h⁻1 (20 mL min⁻1) in downward flow mode. The experimental design was developed using Minitab software (Version 16), which generated a total of 53 runs through its BBD module. This design comprised 32 cube points, 9 center points, and 12 axial points (α = 2.37841), with each run featuring unique combinations of the six operational parameters as detailed in Table S2. Minitab automatically coded all input variables to three standardized levels (-1, 0, and + 1), representing low, middle, and high values respectively (see Table 4), ensuring optimal spacing for response surface modeling. The system’s operational duration, termed ‘contact time’ in this study, was varied from 15 to 360 min. Throughout each experiment, a total volume of 4 L of test solution was continuously recirculated through the columns at a constant flow rate of 20 mL min⁻1. Samples were collected at the end of each interval to monitor removal efficiency progression, while residual concentrations for all water quality parameters are documented in Appendix Table 1. The software’s algorithm calculated the design points to maximize information gain while minimizing the number of experimental runs, thereby creating an efficient framework to evaluate complex interactions among water quality parameters, contact time, and dolomite content in the porous concrete matrix. A second-order polynomial equation was fitted to the experimental results to estimate responses in terms of these six operational parameters30,32.

where \(y\) is the estimated response,\({x}_{i}\) and \({x}_{j}\) are the coded values of the independent variables, \({b}_{0}\), \({b}_{i}\),\({b}_{ii}\) and \({b}_{ij}\) are the constant, linear, quadratic and interaction regression coefficients, respectively, and \(\varepsilon\) is the residual term38. ANOVA was used to evaluate the significance of the predicted model in terms of F-value (Fisher distribution), p-value (Prob > F), “Lack of Fit”, predicted residual error sum of squares (PRESS), and standard deviation.

Generalizes estimation equation (GEE)

Given complex, non-linear relationships between the dependent response variable and operational parameters (initial COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb concentrations, contact time, and dolomite levels) in the presence of dependent observations, we encountered a repeated-measures panel data problem33,34,39. In this context, GEE is used to address these issues33. In this study, six operational parameters, including initial COD, TDS, TSS and Total Pb concentrations, contact time, and dolomite levels, were considered as predictors, while the reduction of water quality parameters served as the response. Since repeated measurements of concentration at t and t-1 were highly correlated (p-value > 0.05), we can use the privilege of GEE. The general equation of multiple GEE is presented as follow:

where \({\beta }_{i} {\prime}\) s are the model coefficients and \(\epsilon\) is the random component of the model. An iterative procedure was employed to predict the model coefficients until the predicted model significantly optimized the fitting process. A link function and a working correlation matrix that depend on the distribution of the dependent variable (Ct) and the correlations between Ct and Ct−1 are required to run GEE. In this context, the non-transforming identity link function as well as the first-order autoregressive working correlation matrix were applied according to Zarei et al.34.

Results and discussion

Mechanical and physical properties of porous concrete

Results of mechanical and physical properties of porous concrete as a function of different dolomite levels are shown in Fig. 2. The data presented in this figure provides compelling evidence that levels of dolomite incorporated into mix design exert a substantial influence on both mechanical and physical properties of porous concrete. As dolomite concentration was incrementally increased from 0 to 15%, a notable enhancement in mechanical characteristics, such as compressive and tensile strengths, was observed. Conversely, physical properties, encompassing hydraulic conductivity and porosity, exhibited a concomitant decline with increasing dolomite levels. Specifically, the compressive strength exhibited a notable increase, rising from 17.5 MPa to 23.6 MPa, while the tensile strength also improved markedly, increasing from 2.55 MPa to 3.1 MPa. Concurrently, hydraulic conductivity decreased from 1.55 mm s-1 to 1.24 mm s-1, and the porosity was reduced from 21.32% to 9.64%. These observed trends can be attributed to fine dolomite filling the pores within the porous concrete matrix. As dolomite content increases, a greater proportion of the pores become occupied by these fine particles, leading to enhanced mechanical properties and reduced physical properties. These findings corroborate results obtained from other research studies10,40,41. Teymouri et al.10 found that incorporating fine grains and adsorbents enhanced compressive strength while decreasing the permeability coefficient and porosity. Additionally, specimens with zeolite exhibited the highest compressive strength, whereas those with pumice had the greatest permeability coefficient. Teymouri et al.21 demonstrated that pervious concrete containing 15% iron slag exhibited improved performance, with increases in compressive strength of 16.12% and tensile strength of 9.23%. However, a decrease in permeability of 16.19% and porosity of 15.29% was noted compared to the control sample. This underscores the importance of carefully optimizing dolomite content in mix design to achieve desired mechanical strength and physical attributes, such as porosity and permeability, for specific applications of porous concrete. By tailoring dolomite levels, it may be possible to design porous concrete with customized properties, thereby expanding its potential applications in areas such as stormwater management, pavement construction, and other civil engineering endeavors. Li et al.42 introduces travertine powder pervious concrete by substituting 25% of the cement with travertine powder and using travertine aggregate in place of limestone aggregate. The compressive strength of travertine powder concrete decreases by just 6.9% to 26.77 MPa when 25% of limestone is substituted with travertine. In contrast, the permeability coefficient significantly increases by 37.8%, reaching 5.36 mm/s. When travertine powder is incorporated, the compressive strength of travertine powder concrete experiences a minor reduction of 3.2% to 25.92 MPa, while the permeability coefficient rises by 14.0% to 6.11 mm/s.

Urban stormwater runoff qualitative parameters

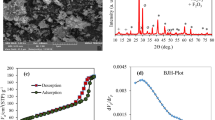

Porous concrete specimens exhibit dual functionality as a pretreatment technology for urban stormwater runoff, serving both as a filtration medium and a settling platform for pollutants. As urban runoff flows through the intricate pore network within these concrete specimens, a filtration process occurs, physically removing particulate matter and contaminants from the liquid stream. Concurrently, the unique porous structure of the concrete facilitates the settling of pollutants, allowing heavier particles and substances to separate from the urban runoff through gravitational forces. This dual mechanism of filtration and settling effectively reduces pollutant concentration10, making porous concrete an attractive pretreatment solution for various wastewater treatment applications. The Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images reveal a distinct inhomogeneity in surface topography of both dolomite particles (Fig. 3a–c) and porous concrete specimens containing dolomite (Fig. 3d–f). Dolomite particles exhibit an assemblage of fine, irregularly shaped particles with varying sizes and well-defined edges. SEM micrographs of porous concrete incorporating dolomite showcase the intricate pore network within the concrete matrix, where fine dolomite particles can be observed occupying void spaces (Fig. 3d). Presence of dolomite potentially influences microstructure and properties of porous concrete, as evidenced by the pore-filling effect. In this phenomenon, clusters of dolomite particles are visible within the pores, partially or completely occupying these void spaces. This pore-filling behavior is likely to impact overall porosity, pore size distribution, and physical properties of porous concrete, potentially influenced by interactions between dolomite particles and the surrounding cement paste. Additionally, SEM images may reveal localized microcracking within the porous concrete matrix, which could be attributed to presence of dolomite particles or their interactions with surrounding cementitious matrix.

COD

The study employed both two-dimensional contour plots and three-dimensional surface plots to provide a comprehensive visual representation of the responses observed at varying levels of independent water quality parameters, as depicted in Fig. 4. These graphical techniques facilitate a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships and interactions between the water quality parameters and the measured responses. ANOVA results presented in Table S3 provide insights into significance of various parameters on COD reduction. P-values, which represent the probability of obtaining observed results by chance, are used to assess statistical significance of each factor. According to this table, parameters such as TDS, COD, dolomite levels, and reaction time have significant effect on COD reduction, as evidenced by their p-values being lower than commonly accepted threshold of 0.05. This suggests that changes in these parameters substantially influence COD removal efficiency. On the other hand, effects of Total Pb concentration and TSS are considered non-significant, as their p-values exceed 0.05. This implies that variations in these parameters may not substantially impact COD reduction within studied range. Furthermore, ANOVA results indicate that both linear and squared effects of parameters are statistically significant in influencing COD removal. However, interaction effects between parameters are found to be non-significant, suggesting that individual effects of each parameter are more prominent than their combined interactions (Table S4). Based on information provided and observation from Fig. 4a, it can be inferred that COD removal is enhanced by increasing both dolomite levels and reaction time. The contour plot shows that when dolomite levels exceed 12% and reaction time is longer than 125 min, COD removal efficiency exceeds 90%. According to Fig. 4b, it can be inferred that at optimum reaction time, COD removal is negatively impacted and falls below 90% when TDS concentration exceeds 800 mg L-1. According to Fig. 4c, when reaction time is less than 85 min, COD removal efficiency is lower than 85% regardless of initial COD concentration level. Figure 4d also demonstrates that when initial TSS concentrations are between 380–780 mg L-1, regardless of the desired Total Pb concentrations, optimum level of COD removal (> 86.5%) is achieved. Similar results were obtained in the study by Teymouri et al.10, which showed that porous concrete containing fine-grained mineral adsorbents reduced TSS, BOD, and COD by 40%, 48%, and 30.5%, respectively, in municipal wastewater. Teymouri et al.21, who demonstrated that pervious concrete containing 15% iron slag effectively reduces urban runoff contaminants, with COD, TSS, and turbidity decreasing by 69.75%, 68%, and 69%, respectively, also reported similar findings. This reduction is attributed to its porous nature and the reduced size of pores, which allows for better pollutant capture. A similar trend was also observed in the study by Abedi-Koupai et al.9, which indicated that porous concrete containing iron slag combined with a sand filter significantly improved the removal efficiencies of COD, turbidity, Total Pb, and TSS by 43%, 91%, 95%, and 70%, respectively. Wu et al.43 indicate that the addition of zeolite powder to porous asphalt concrete has no significant effect on the road performance of the material. However, it enhances the removal rates of suspended solids, COD, Zn(II), and Total Pb by 6.4%, 25.2%, 20.6%, and 23.5%, respectively. Zhang et al.44 developed a photocatalytic water purification pavement coated with nano-TiO2, enhancing the water purification performance of porous concrete. The results indicated that the removal rates of COD could reach 50%. In a study by Faisal et al.45, the physical characteristics and wastewater purification efficiency of pervious concrete pavement samples were evaluated, along with the influence of aggregate size and water-cement ratio. The prepared pervious concrete pavement demonstrated the best COD removal of nearly 54% when using large aggregate sizes between 9 and 19 mm. Additionally, the samples exhibited the highest BOD removal of approximately 79% with the same large aggregate size.

Contour and surface plots for pollutant removal; COD Removal: (a) time and dolomite; (b) time and TDS; (c) time and COD; (d) TSS and Total Pb. TDS Removal: (e) time and COD; (f) time and TDS; (g) time and dolomite; (h) TDS and dolomite; (i) COD and dolomite; (j) TDS and COD. TSS Removal: (k) TSS and dolomite. Total Pb Removal: (l) time and dolomite; (m) time and Total Pb; (n) Total Pb and dolomite.

Based on the information provided from Table S3, a quadratic polynomial model can be developed to represent relationship between COD removal and the input parameters. Model was constructed using coded values of significant parameters (those with p-values < 0.05), while non-effective parameters (p-values > 0.05) were removed from model.

Accuracy of quadratic polynomial model is demonstrated by R2 value of 0.992, adjusted R2 value of 0.983, and standard error of estimate (SE) of 1.43. These statistical measures indicate high degree of precision and reliability in model’s predictions. Furthermore, the lack-of-fit P-value for COD removal exceeded 0.05, indicating that the quadratic polynomial model adequately describes the relationship between input parameters and COD removal efficiency. Consequently, regression equation derived from this model is valid and can be employed to predict COD removal with high level of confidence within studied parameter space. Notably, negative signs associated with TDS and initial COD concentration suggest an antagonistic effect of these variables on COD removal. This implies that an increase in TDS or initial COD concentration would lead to a decrease in the efficiency of COD reduction. Conversely, the positive signs corresponding to dolomite levels and reaction time indicate a synergistic effect, suggesting that an increase in these factors would result in improved COD removal. According to Eq. (5), the removal of COD is more sensitive to TDS, followed by dolomite levels, reaction time, and initial COD concentration.

TDS

Interactive effects of reaction time versus initial COD concentration (Fig. 4e) and initial TDS concentration (Fig. 4f) on removal of COD are investigated, while keeping other parameters constant. These plots demonstrate that impact of initial TDS concentration is more pronounced than that of initial COD concentration. Notably, when reaction time exceeds 150 min, COD removal efficiency falls within the range of 67.5–70%, regardless of desired initial COD concentration. However, this removal efficiency declines to 60–65% when initial TDS concentration reaches 1500 mg L-1. This observation suggests that while initial COD concentration has a limited effect on removal efficiency at longer reaction times, initial TDS concentration plays a more crucial role. Contour plot in Fig. 4g illustrates both reaction time and dolomite concentration exhibit positive influence on TDS removal. Plot reveals that when the dolomite level exceeds 12.5% and reaction time surpasses 150 min, removal efficiency of TDS can be achieved at levels greater than 75%. Figure 4h,i depict interactive effects of dolomite levels with initial TDS and COD concentrations, respectively, on removal efficiency of TDS. Examination of these contour plots reveals that while relationships between dolomite levels and both TDS and COD concentrations appear linear, but slope associated with COD is steeper. This observation suggests that impact of initial COD concentration on TDS removal efficiency is comparatively lower than that of initial TDS concentration. Contour plot depicted in Fig. 4j indicates inverse relationship between removal efficiency of TDS and initial concentrations of both TDS and COD. From this plot, it can be inferred that decreasing initial concentrations of TDS and COD enhances removal of TDS from treated water. Data presented in Supplementary Table S5 provides the foundation for developing a quadratic polynomial model to characterize relationship between removal efficiency of TDS and various input parameters influencing treatment process.

Quadratic polynomial model exhibits high degree of accuracy in predicting TDS removal efficiency, as evidenced by R2 value of 1, adjusted R2 value of 1, and SE of 0.205. Notably, negative coefficients associated with initial TDS and COD concentrations in model suggest antagonistic effect, implying that increases in these parameters would adversely impact TDS removal efficiency. Conversely, positive coefficients corresponding to dolomite levels and reaction time indicate a synergistic effect, where higher values of these variables enhance removal of TDS from treated water. This analysis provides valuable insights into relative influence of input parameters and their interactions, enabling optimization of treatment process for maximizing TDS removal. ANOVA results presented in Supplementary Table S6 reveal that the linear terms, squared terms, and interaction terms of input parameters exhibit statistical significance in their influence on TDS removal efficiency, as evidenced by corresponding p-values.

TSS

Data compiled in Supplementary Table S7 lays groundwork for formulating quadratic polynomial model to elucidate relationship between removal efficiency of TSS and various input parameters governing treatment process.

Quadratic polynomial model demonstrates high level of accuracy in predicting TSS removal efficiency, as evidenced by R2 value of 0.989, adjusted R2 value of 0.976, and relatively low SE of 1.425. A noteworthy observation from model coefficients is negative sign associated with initial TSS concentration term, suggesting an antagonistic effect. This implies that an increase in the initial TSS concentration would hinder removal efficiency of TSS. Conversely, positive coefficients corresponding to dolomite levels and reaction time indicate a synergistic effect, wherein higher values of these parameters contribute to enhanced TSS removal from treated water. Surface plot depicted in Fig. 4k illustrates interactive effects of dolomite level and initial TSS concentration on removal efficiency of TSS. Examination of this plot reveals direct relationship between dolomite level and TSS removal efficiency when initial TSS concentration is decreased. Specifically, as dolomite level is increased in conjunction with reduction in initial TSS concentration, removal efficiency of TSS exhibits increasing trend. ANOVA results presented in Supplementary Table S8 indicate linear and squared terms of input parameters have statistically significant influences on TSS removal efficiency, as evidenced by their respective p-values. In contrast, interaction terms do not demonstrate statistical significance in their impact on TSS removal efficiency.

Total Pb

As depicted in Fig. 4l, interaction between reaction time and dolomite level exhibits a significant effect on removal efficiency of Total Pb ions. Plot reveals that increasing both of these parameters concurrently leads to enhancement in removal of Total Pb ions from treated water. Figure 4m depicts interactive effect between reaction time and initial Total Pb concentration on removal efficiency of Total Pb ions. The plot reveals that for reaction times lower than 150 min, initial Total Pb concentration has a significant impact on removal efficiency. However, beyond 150 min of reaction time, removal efficiency of Total Pb ions exceeds 90% across entire range of initial Total Pb concentrations evaluated. The optimum reaction time for maximizing Total Pb removal was determined to be 275 min, at which point more than 93% of Total Pb ions were removed under the following conditions: TDS = 960 mg L-1, COD = 104.5 mg L-1, TSS = 501.5 mg L-1, and a dolomite level of 10%. Figure 4n illustrates that removal efficiency of Total Pb ions exhibits an increasing trend with higher dolomite levels and lower initial Total Pb concentrations. However, examination of surface plot suggests that influence of initial Total Pb concentration on removal efficiency is relatively less pronounced compared to impact of dolomite level. Li et al.42 demonstrate that pervious concrete pavement made with travertine waste and sand can remove Cd(II) and Cu(II) at rates ranging from 42.0% to 99.4% and 79.5% to 95.4%, respectively. Additionally, it achieves a removal rate exceeding 98% for Pb2⁺ after 30 min. Khankhaje et al.46 assessed the removal of heavy metals from stormwater runoff using pervious concrete pavement made with seashells and oil palm kernel shells. The heavy metal removal efficiency for the mixture containing seashells ranged from 37 to 93%, surpassing the control mixture, which achieved 39% to 73%. In contrast, the specimens with kernel shell showed a removal rate between 14 and 63%, which was lower than that of the control mixture.

Data presented in Supplementary Table S9 provides the foundation for developing a quadratic polynomial model that can describe relationship between removal efficiency of Total Pb ions and various input parameters influencing the treatment process.

Quadratic polynomial model exhibits remarkable level of accuracy in predicting Total Pb removal efficiency, as demonstrated by R2 value of 1, adjusted R2 value of 1, and low SE of 0.0468. A notable observation from model coefficients is negative sign associated with initial Total Pb concentration term, suggesting an antagonistic effect. This implies that an increase in initial Total Pb concentration would adversely impact removal efficiency of Total Pb ions. In contrast, positive coefficients corresponding to dolomite levels and reaction time indicate a synergistic effect. Higher values of these parameters contribute to enhanced removal of Total Pb ions from treated water. According to ANOVA results showcased in Supplementary Table S10, linear terms, squared terms, and interaction terms of input parameters demonstrate statistical significance in their impact on the Total Pb ions removal efficiency, as indicated by their respective p-values below chosen level of significance.

Prediction by RSM-BBD

The observed values were graphed against estimated values obtained from the RSM-BBD model, with results for COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb depicted in Fig. 5a–d, respectively. These graphs facilitate a visual comparison between experimental data and the model’s predictions, enabling an assessment of the model’s accuracy and reliability in estimating removal efficiencies for various water quality parameters. The close alignment of data points to the y = x line in the four figures indicates a strong correlation between experimentally obtained values and the model’s predicted response values. These findings are consistent with observations reported by previous researchers in related studies47,48. The effectiveness and reliability of the RSM-BBD model in determining water quality parameters are illustrated through various diagnostic plots. Figure 5e–h depict the histogram of residuals, the plot of residuals versus fitted values, the normal probability plot of residuals, and the plot of residuals versus observation order, respectively, for the TDS response. Corresponding plots for COD, TSS, and Total Pb are presented in Fig. S2. The histogram of residuals indicates that the distribution closely resembles a normal curve (Fig. 5e). Figure 5f illustrates a random scatter of residuals, suggesting constant variance across original observations, a desirable characteristic for the model’s reliability. The residual plot shows that most data points cluster within the range of -0.125 to + 0.125, indicating a good fit of the model to the experimental data (Fig. 5g). The residuals versus observation order plot demonstrates that the residual values oscillate around the central line, falling within a maximum range of ± 0.5, corroborating the model’s accuracy (Fig. 5h). A comparable trend was observed for the COD, TSS, and Total Pb ion responses (Fig. S2).

Scatter plot between observed and estimated values for (a) COD, (b) TDS, (c) TSS, (d) Total Pb, (e) Histogram chart of residuals, (f) plot of residuals versus fitted values, (g) normal probability plot of residuals, and plot of residuals versus observations order (h) for TDS removal by porous concrete containing dolomite adsorbent.

Prediction by GEE

The present study investigates the influence of independent factors, namely initial COD, TDS TSS and Total Pb concentrations as well as contact time, and dolomite levels, on the removal efficiencies of COD, TDS TSS and Total Pb. All factors were incorporated into the analysis, and the GEE technique was applied. Table S11 summarizes the results obtained from the GEE technique specifically for TDS removal. As indicated in Table S11, the equation derived from the GEE analysis for predicting TDS removal can be represented as follows:

The results indicate that, when considering the effects of significant factors, terms for dolomite level and reaction time exhibited positive effects (B > 0, p < 0.05) on TDS removal efficiency, while terms for initial COD and TDS concentrations had negative effects (B < 0, p < 0.05). These findings suggest that higher dolomite levels and longer reaction times favored enhanced TDS removal, whereas higher initial COD and TDS concentrations hindered the removal process. Furthermore, based on Wald Chi-Square statistic values, initial TDS concentration had the most significant impact on TDS removal efficiency, followed by dolomite level, reaction time, and initial COD concentration, respectively. The obtained GEE model exhibits remarkable accuracy in predicting the TDS removal efficiency, evident from high R2 value of 0.998, adjusted R2 value of 0.998, and SE of 2.75. While both RSM-BBD and GEE models perform well with the given dataset, RSM-BBD model demonstrates superior performance with higher R2 and adjusted R2 values, as well as a lower SE.

Table S12 summarizes the results obtained from the GEE technique specifically for COD removal. As indicated in Table S12, the equation derived from the GEE analysis for predicting the COD removal efficiency can be expressed as follows:

The results reveal that, when considering the effects of significant factors, terms for dolomite level and reaction time exhibited positive effects (B > 0, p < 0.05) on COD removal efficiency. Conversely, terms for initial COD and TDS concentrations had negative effects (B < 0, p < 0.05). These findings indicate that higher dolomite levels and longer reaction times facilitated enhanced COD removal, whereas higher initial COD and TDS concentrations impeded the removal process. Furthermore, an analysis of Wald Chi-square values revealed that initial TDS concentration had the most pronounced impact on COD removal efficiency, followed by reaction time, dolomite level, and initial COD concentration, respectively. The derived GEE model demonstrates remarkable accuracy in predicting COD removal efficiency, as evidenced by high R2 value of 0.998, adjusted R2 value of 0.998, and low SE of 3.68. A comparison between GEE and RSM-BBD models reveals that while both perform well with the given dataset, the RSM-BBD model outperforms the GEE model in terms of higher R2 and adjusted R2 values, as well as a lower SE.

Tables S13 and S14 present the equations derived from the GEE model, which can be used to predict the removal of TSS and Total Pb ions, as represented by Eqs. 11 and 12, respectively.

The analysis indicates that, when controlling for significant factors, dolomite level and reaction time showed significant positive effects (p < 0.05) on the removal efficiency of both TSS and Total Pb ions. In contrast, initial concentrations of TSS and Total Pb ions had significant negative effects (p < 0.05) on the removal efficiency of TSS and Total Pb ions, respectively. Furthermore, Wald Chi-Square values indicate that initial TSS concentration had the most significant influence on TSS removal efficiency, followed by dolomite level and reaction time. In contrast, dolomite level had the greatest impact on Total Pb ions removal efficiency, with reaction time and initial Total Pb concentration being the second and third most significant factors, respectively. For TSS removal, the derived GEE model exhibits an excellent fit, with a high R2 value of 0.999 and an adjusted R2 value of 0.998. Similarly, the GEE model demonstrates remarkable accuracy in predicting Total Pb removal, as evidenced by the high R2 value of 0.998 and the adjusted R2 value of 0.998. SE for the removal of TSS and Total Pb ions were found to be 3.22 and 3.49, respectively, using the GEE model. These relatively higher SE values, compared to those obtained from the RSM-BBD model, indicate that RSM-BBD model demonstrates superior accuracy in predicting removal efficiencies of TSS and Total Pb ions for the studied system. Goodness of the GEE fitted model was further evaluated through residual analysis. Normality of the residuals was assessed using a probability plot, as shown in Fig. 6. The normal probability plot indicates residuals satisfy the normality assumption, as data points closely align with the reference line. Additionally, the residual values oscillate around the central line, falling within the ranges of − 2.5 to 2, − 1.5 to 2, − 2 to 2, and − 2.5 to 2 for TDS, COD, TSS, and Total Pb, respectively. Additionally, Fig. S3resents the plot of residuals versus fitted values for TDS, COD, TSS, and Total Pb ions. As evident from Fig. S3, the points are randomly distributed about the horizontal axis, indicating the assumption of homoscedasticity is satisfied. Consequently, the GEE model adequately captures the variations in these water quality parameters, demonstrating its suitability for modeling the removal efficiencies of TDS, COD, TSS, and Total Pb ions in the studied system. Similarly, Lotfi et al.17 predicted BOD, COD, TSS, and TDS using a novel hybrid linear-nonlinear methodology.

Proposed mechanism

Combination of porous concrete’s favorable hydraulic properties and dolomite adsorbent’s pollutant removal mechanisms allow this composite material to effectively treat stormwater runoff and mitigate impact of urban pollution on downstream water bodies. Dolomite is a calcium-magnesium carbonate mineral that has a high affinity for adsorbing various pollutants commonly found in stormwater runoff, such as heavy metals, oil and grease, dissolved solids and suspended solids. As stormwater passes through porous concrete, dolomite adsorbent traps and removes these pollutants through a few key mechanisms: (a) Adsorption—Porous structure and large surface area of dolomite provide abundant sites for pollutants to bind to mineral surface through adsorption. (b) Ion exchange—Calcium and magnesium ions in dolomite can undergo ion exchange with heavy metal cations, effectively removing them from water. (c) Precipitation—Alkaline nature of dolomite (pH around 8–9) can promote precipitation of dissolved metals as insoluble hydroxides or carbonates, which are then trapped within the porous matrix. (d) Filtration—Porous concrete structure acts as a physical filter, straining out suspended solids and trapping particulate-bound pollutants as water flows through. Combination of these adsorption, ion exchange, precipitation, and filtration mechanisms allow dolomite adsorbent within porous concrete to effectively remove a wide range of pollutants commonly found in urban stormwater runoff. This helps mitigate environmental impact of runoff on receiving water bodies. The dolomite-modified porous concrete system achieves TDS reduction through an integrated, multi-stage removal process that combines physico-chemical mechanisms in a hierarchical manner. This process is divided into three stages:

-

(a)

Primary removal stage (0–60 min)

This stage includes ion exchange dominance and electrostatic attraction. Rapid displacement of monovalent cations (Na⁺, K⁺) by Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺ at dolomite surface sites occurs through the following ion exchange mechanism:

At pH values below 8.2, positively charged dolomite surfaces adsorb Cl⁻ and SO42⁻ ions through electrostatic attraction.

-

(b)

Secondary removal stage (60–240 min)

Continued removal involves more complex physico-chemical interactions, including further co-precipitation and surface complexation. The released CO₃2⁻ ions react with divalent metals (Pb2⁺, Ca2⁺) to form mixed carbonates through co-precipitation.

The ≡CO32⁻ sites on dolomite chemically bind cations (e.g., Na⁺, Pb2⁺), while Mg–OH and Ca–OH surface groups adsorb anions (Cl⁻, SO42⁻) through surface complexation.

-

(c)

Tertiary removal stage (> 240 min).

Long-term processes dominate, including colloidal entrapment, where nano-scale TDS particles (1–100 nm) are physically filtered and retained by the porous matrix.

Process optimization and validation of the RSM-BBD

Figure 7 presents the RSM optimization using BBD to determine the ideal operational conditions for maximizing pollutant removal efficiency. The figure comprehensively integrates key components, demonstrating the model’s predictive capabilities and experimental validation. The RSM-BBD framework analyzed six critical parameters within specified ranges: COD (63–146 mg L⁻1), TDS (320–1600 mg L⁻1), TSS (66–937 mg L⁻1), Total Pb (2–5 mg L⁻1), contact time (15–360 min), and dolomite content (5–15%). Through 53 systematic experimental runs, the model generated: second-order polynomial equations (Eqs. 5–8) describing each pollutant’s removal kinetics, three-dimensional response surfaces illustrating parameter interactions, and desirability functions to optimize multiple responses simultaneously. According to the RSM-BBD model predictions, the maximum removal efficiencies achieved under the optimal conditions were as follows: 87.48% for TDS with a desirability of 0.875, 99.85% for COD with a desirability of 0.999, 98.49% for TSS with a desirability of 0.985, and 97.17% for Pb(II) with a desirability of 0.972. These optimal conditions corresponded to initial concentrations of 340 mg L⁻1 for TDS, 63.97 mg L⁻1 for COD, 66 mg L⁻1 for TSS, and 2 mg L⁻1 for Pb(II), along with a reaction time of 360 min and a dolomite level of 13.29% (Fig. 7).

A strong agreement was observed between predicted and experimental removal efficiencies, with minimal deviations across key parameters. For TDS, the predicted removal was 87.48%, closely matching the experimental value of 87.12%, yielding a marginal error of 0.36%. COD exhibited near-complete removal, with predicted and experimental efficiencies of 99.85% and 98.05%, respectively, resulting in a 1.80% discrepancy. TSS showed high removal rates, with predictions at 98.49% and experimental results at 97.16%, differing by only 1.33%. Similarly, Total Pb removal was highly efficient, with predicted (97.17%) and experimental (96.88%) values differing by a negligible 0.29%.Further validation through desirability function analysis confirmed the robustness of the optimization. The individual desirability scores ranged from 0.875 for TDS to 0.999 for COD, reflecting near-ideal performance for critical response variables. The composite desirability exceeded 0.97, underscoring the effectiveness of the multi-objective optimization framework in achieving balanced and high-performance outcomes across all evaluated parameters.

Real urban stormwater treatment

To evaluate the feasibility of implementing the proposed system for removal of target pollutants on a large scale, real samples from impervious surfaces and overland flows were collected during three storm events. After filtration through a 0.45 mm mesh filter to remove leaves, twigs, and gross debris, the real urban stormwater runoff was used as the feed solution for further treatment. The stormwater solution with the highest concentration of pollutants (1560 mg L⁻1 TDS, 140 mg L⁻1 COD, 920 mg L⁻1 TSS, and 500 µg L⁻1 Total Pb) was subsequently introduced into porous concrete containing a 15% dolomite adsorbent using a peristaltic pump. Experiments were conducted with a contact time of 360 min and a hydraulic loading rate of 153 L m⁻2 h⁻1 (20 mL min⁻1), simulating large-scale application of the system for urban stormwater runoff treatment. Under these conditions, the system demonstrated highly effective pollutant removal, achieving complete elimination (100%) of total Pb, along with substantial reductions of 83% for TSS, 78.91% for COD, and 64.68% for TDS (Table 5). Urban stormwater lead predominantly exists in particulate forms (70–90%) associated with fine solids (< 10 μm) from traffic wear, paint residues, and atmospheric deposition4,6. While dolomite’s Ca2⁺/Mg2⁺ sites theoretically adsorb ionic Pb2⁺, the column’s exceptional lead removal (100%) likely reflects combined mechanisms such as physical filtration of Pb-bearing particulates by the porous concrete matrix (pore size 1–5 mm), electrostatic attraction of charged colloids to dolomite surfaces, and dissolution/re-precipitation of particulate lead at dolomite’s alkaline surface.

The system’s performance aligns with the RSM-BBD optimization (Sect. “Process optimization and validation of the RSM-BBD”), which predicted near-complete Pb removal (> 97%) at 13.29% dolomite and 360 min contact time, with minimal deviations (< 2%) for other pollutants. These findings highlight the potential of the porous concrete-dolomite adsorbent system as a promising pretreatment technology for urban stormwater remediation, particularly in regions with high heavy metal loads. However, long-term maintenance such as periodic cleaning to mitigate clogging is recommended to sustain permeability and adsorption capacity in field applications.

Adsorption isotherms

The analysis of the equilibrium data to determine the capacity of the porous concrete containing dolomite adsorbent for the adsorption of COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb was carried out using the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm models. The results revealed that the Freundlich isotherm model provided a better fit for all quality parameters of urban stormwater runoff (R2 > 0.974) compared to the Langmuir model (Table S15). The Freundlich model is an empirical equation that suggests the surface of the porous concrete containing dolomite is heterogeneous and possesses varying pore sizes, which can facilitate multilayer adsorption. In the Freundlich model, KF represents the maximum adsorption capacity, and n is the adsorption intensity parameter, which are indicative of the affinity of the porous concrete containing dolomite towards the adsorption of COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb49,50. The value of 1/n in the range of 0 < 1/n < 1 is considered favorable for adsorption, whereas 1/n > 1 indicates an unfavorable adsorption isotherm49. The obtained values of 1/n for all quality parameters of urban stormwater runoff demonstrate that the adsorption of COD, TDS, TSS, and Total Pb onto the porous concrete containing dolomite is favorable (see Table S15). Higher KF values correspond to a greater adsorption capacity, and the values obtained were 2.65, 3.71, 4.53, and 12.55 for TDS, COD, TSS, and Total Pb ions, respectively. These results suggest that the porous concrete containing dolomite exhibited the highest adsorption capacity for Total Pb ions, followed by TSS, COD, and TDS.

The sensitivity analysis and significance of dolomite in porous concrete

Sensitivity analysis, based on Wald Chi-Square values, revealed that dolomite adsorbent dosage was the most influential factor affecting removal efficiency of Total Pb ions. Furthermore, while dolomite level exhibited the second-highest impact on removal of TSS and TDS, it was identified as the third most significant factor influencing reduction of COD in stormwater runoff. The use of dolomite as an adsorbent in the porous concrete matrix for treating urban stormwater runoff holds significant importance in this study due to the following reasons: (1) Reduced cement content: Porous concrete requires less cement compared to conventional concrete, lowering material costs. (2) Low-cost dolomite: Dolomite is an inexpensive and widely available natural mineral, making it a cost-effective adsorbent material. (3) Minimized transportation costs: Utilizing locally sourced dolomite reduces raw material transportation costs. (4) In-situ application: The system is designed for in-situ application, eliminating the need for additional treatment facilities and associated costs. (5) Extended service life: Incorporating dolomite can potentially extend the concrete’s service life, reducing long-term maintenance and replacement costs. (6) Dolomite, a natural calcium magnesium carbonate mineral, effectively and economically removes heavy metals like Total Pb from urban stormwater runoff. (7) Dolomite can be regenerated and reused after exhaustion, promoting sustainability and cost-effectiveness, enabling a circular stormwater treatment approach. The adsorption performance of porous concrete improves significantly with higher dolomite content, particularly for TDS (Fig. 8a), COD (Fig. 8b), TSS (Fig. 8c), and total Pb removal (Fig. 8d). Experimental results reveal a progressive enhancement in removal efficiency as dolomite concentration rises from 0 to 15%: TDS removal increases from 40.3% to 64.68%, COD from 53.12% to 78.91%, TSS from 57.12% to 83%, and total Pb from 62.18% to 96% when treating influent containing 1600 mg L-1 TDS, 146 mg L-1 COD, 937 mg L-1 TSS, and 5 mg L-1 total Pb. Notably, the baseline porous concrete (0% dolomite) exhibits substantial removal capacity attributable to two key factors: (1) the inherent adsorptive properties of pumice within the concrete matrix, and (2) the physical filtration mechanism enabled by the material’s porous structure. This dual functionality of the unmodified system provides fundamental treatment capacity, while dolomite incorporation introduces additional adsorption sites through its calcium-magnesium carbonate matrix, particularly enhancing heavy metal removal via ion exchange and surface complexation mechanisms.

Limitation of the proposed technique and possible solution

Potential limitations of using a porous concrete matrix containing dolomite adsorbent for treating urban stormwater runoff include: (1) Limited treatment capability for removing contaminants like nutrients, pathogens, or organic pollutants; (2) Sensitivity to pH and water chemistry variations, which could reduce adsorption efficiency or lead to leaching; (3) Periodic maintenance, cleaning, or replacement requirements, increasing operational costs; (4) Potential long-term environmental impact, including leaching of contaminants or disposal of spent adsorbents.

Possible solutions to address these limitations are: (1) Periodic cleaning or maintenance, such as backwashing, surface washing, chemical treatment, or physical removal of clogged concrete blocks, to ensure continued effectiveness after each storm event or after a certain number of events. (2) Regular monitoring and inspection, involving visual inspections, permeability tests, or other evaluation techniques to assess clogging, fouling, and adsorption capacity over time. (3) Replacement or regeneration of the porous concrete blocks or dolomite adsorbent, depending on the extent of clogging or saturation, exploring methods for adsorbent regeneration to enhance system longevity and cost-effectiveness. (4) Pretreatment or filtration steps upstream of the blocks to remove larger particles or debris from the stormwater runoff before adsorption, reducing the rate of clogging and extending service life. (5) Adaptive design and optimization of the porous concrete blocks, including adjustments to the dolomite adsorbent dosage and other parameters, based on performance data and experience from multiple storm events, to improve durability, adsorption capacity, and ease of maintenance.

Implications for typical porous pavement systems

The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of dolomite-modified porous concrete for stormwater treatment, but their translation to real-world applications requires careful consideration of operational conditions. The Thomas model provides a robust framework for predicting system longevity under dynamic flow conditions51, with the adsorption process governed by the equation:

where kinetic coefficients were determined as 0.0005 L min-1·mg-1 for COD, 0.0001 L min-1·mg-1 for TDS, 0.0003 L min-1·mg-1 for TSS, and 0.001 L min-1·mg-1 for Pb. Laboratory tests under forced flow (153 L/m2h) revealed distinct contaminant-specific removal patterns, with Pb showing the longest breakthrough time (1670 h to 50% saturation) due to dolomite’s strong adsorption capacity, while TDS and TSS saturated more rapidly (1–1.7 h). However, field conditions differ significantly from controlled experiments. Gravity-driven drainage in typical porous pavements operates at lower hydraulic loading (50–200 L/m2h) and shorter contact times (0.25–2 h for natural infiltration versus 6 h in the lab). These factors reduce dissolved contaminant (COD, TDS) removal efficiency by 10–20% compared to lab results, while particulate-bound pollutants (TSS, Pb) remain effectively captured through physical filtration. Adjusting for field conditions, projected 50% breakthrough times decrease to 0.1–0.6 h for TDS/TSS and 220–500 h for Pb, necessitating tailored maintenance strategies. Clogging presents a key challenge for long-term performance. The system’s 83% TSS removal efficiency suggests accumulation of ~ 0.2 kg/m2 of solids after 1.4 years (assuming 30 storms/year), requiring vacuum sweeping or pressure washing to restore permeability. The system’s long-term performance can be enhanced through pretreatment using vegetated filter strips or sediment forebays (reducing TSS loading by 40%), combined with a layered construction approach featuring: (1) an upper 10 cm dolomite-enriched layer (12% content for optimized Pb/COD removal), (2) a lower 15–20 cm standard mix for structural support, and (3) a geotextile-wrapped underdrain to retain fines. Maintenance protocols should include annual vacuum sweeping for Pb/COD units, quarterly cleaning for TDS/TSS systems, and ASTM C1701 permeability testing when infiltration rates fall below 50 mm/h, ensuring sustained treatment efficiency while preventing clogging-related performance decline. For heavy traffic areas (e.g., parking lots), a 25 cm thick section with dolomite enrichment in the upper layer balances treatment and durability. Residential applications (walkways, driveways) can use 15 cm monolithic designs with 8% dolomite, paired with bioswales for enhanced particulate removal. The Thomas model confirms Pb removal remains effective for 5+ years without adsorbent replacement, making it ideal for long-term metal remediation. In contrast, COD/TSS units require annual maintenance due to faster saturation. These findings enable lifecycle cost optimization—prioritizing dolomite for Pb hotspots while using conventional porous concrete with pretreatment for particulate control. Table 6 presents the projected field performance of dolomite-modified porous concrete.

Conclusion

The findings of this research demonstrate the promising potential of dolomite-incorporated porous concrete for applications in urban green spaces. The material exhibites favorable performance in terms of compressive and tensile strength, as well as effective removal of contaminants present in urban stormwater runoff. Integrating dolomite adsorbent with porous concrete offers dual benefits: a cost-effective approach for urban runoff treatment, potentially reducing overall remediation expenses, and enhanced overall adsorption capacity for efficient pollutant removal from urban stormwater runoff. The system achieved complete elimination of Total Pb (100% removal) and substantial reductions in other key pollutants, including 83% decrease in TSS, 78.91% reduction in COD, and 64.68% decrease in TDS. Sensitivity analysis revealed dolomite adsorbent dosage as the most influential factor affecting Total Pb ion removal efficiency, while dolomite level exhibited the second-highest impact on TSS and TDS removal, and the third most significant factor influencing COD reduction. Based on the findings, a porous concrete matrix incorporating a 15% dosage of dolomite adsorbent is recommended for implementation in urban green spaces and pedestrian walkways. This optimized material composition exhibits desirable properties for effective urban stormwater management, allowing efficient stormwater infiltration and capturing and treating urban runoff by removing various pollutants, such as suspended solids, organic matter, and heavy metals. However, potential limitations include clogging and fouling, maintenance and replacement requirements, and limited capability in removing other contaminants such as nutrients, pathogens, or organic pollutants. Porous nature of concrete matrix may be susceptible to clogging and fouling, reducing permeability and hydraulic conductivity, which could significantly impact system’s overall performance. Periodic maintenance, cleaning, or replacement of clogged or fouled components may be required, increasing operational costs and potentially causing system downtime. If clogging becomes severe, washing or flushing the clogged concrete specimens before next storm event could be necessary, using methods like backwashing, surface washing, chemical treatment, or physical removal. Furthermore, the long-term environmental impact of the proposed porous concrete-dolomite adsorbent system, such as potential leaching of contaminants, as well as its sensitivity to pH and water chemistry changes, and its capability for effectively removing other contaminants such as nutrients, pathogens, or organic pollutants, may need further comprehensive evaluation to ensure the system’s sustainability and environmental compatibility.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.

References

Tang, J. Y. M. et al. Toxicity characterization of urban stormwater with bioanalytical tools. Water Res. 47, 5594–5606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112463 (2013).

Amiri, M. J., Eslamian, S., Arshadi, M. & Khozaei, M. Water recycling and community. In Urban water reuse handbook (ed. Eslamian, S.) 261–273 (CRC Press, 2015).

Alimohammadi, V. et al. Stormwater runoff treatment using pervious concrete modified with various nanomaterials: A comprehensive review. Sustainability. 13(15), 8552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158552 (2021).

Müller, A., Österlund, H., Marsalek, J. & Viklander, M. The pollution conveyed by urban runoff: A review of sources. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 136125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136125 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Research on nonpoint source pollution assessment method in data sparse regions: A case study of Xichong river basin. China. Adv. Meteorol. 2015, 519671. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/519671 (2015).

Pamuru, S. T., Forgione, E., Croft, K., Kjellerup, B. V. & Davis, A. P. Chemical characterization of urban stormwater: Traditional and emerging contaminants. Sci. Total Environ. 813, 151887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151887 (2022).

Liu, C., Lu, J., Liu, J., Mehmood, T. & Chen, W. Effects of lead (Pb) in stormwater runoff on the microbial characteristics and organics removal in bioretention systems. Chemosphere 253, 126721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126721 (2020).

O’Connor, D. et al. Lead-based paint remains a major public health concern: A critical review of global production, trade, use, exposure, health risk, and implications. Environ. Int. 121, 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.052 (2018).

Abedi-Koupai, J., Saghaian Nejad, S., Mostafazadeh-Fard, S. & Behfarnia, K. Reduction of urban storm-runoff pollution using porous concrete containing iron slag adsorbent. J. Environ. Eng.-ASCE. 142(2), 04015072 (2016).

Teymouri, E., Mousavi, S. F., Karami, H., Farzin, S. & Hosseini Kheirabad, M. Municipal Wastewater pretreatment using porous concrete containing fine-grained mineral adsorbents. J. Water Process. Eng. 36, 101346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101346 (2020).

Bahrami, M., Amiri, M. J. & Badkubi, M. Application of horizontal series filtration in greywater treatment: A semi-industrial study. Australas. J. Water Resour. 24(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13241583.2020.1824610 (2020).

Nishat, A. et al. Wastewater treatment: A short assessment on available techniques. Alex. Eng. J. 76, 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.06.054 (2023).

Finnerty, C. T. K. et al. The future of municipal wastewater reuse concentrate management: Drivers, challenges, and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c06774 (2024).

Meng, X., Huang, Z. & Ge, G. Upgrade and reconstruction of biological processes in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Desalin Water Treat. 317, 100299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100299 (2024).

Lasaki, B. A., Maurer, A. & Schönberger, H. A modified integrated physical advanced primary treatment to enhance particulate organic carbon removal in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Sci. Technol. 89(4), 1094–1105. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2024.044 (2024).

Amiri, M. J., Bahrami, M., Badkouby, M. & Kalavrouziotis, I. K. Greywater treatment using single and combined adsorbents for landscape irrigation. Environ. Process 6, 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40710-019-00362-1 (2019).

Lotfi, K. et al. Predicting wastewater treatment plant quality parameters using a novel hybrid linear-nonlinear methodology. J. Environ. Manage. 240, 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.03.137 (2019).

Karimi, H., Teymouri, E., Mousavi, S. F. & Farzin, S. Experimental investigation of the effect of adding LECA and pumice on some physical properties of porous concrete. Eng. J. 22(1), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.4186/ej.2018.22.1.205 (2018).

ACI (American Concrete Institute). Pervious concrete. ACI 522R-06, ACI-report (Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2006).

Javaheri-Tehrani, M., Mousavi, S. F., Abedi-Koupai, J. & Karami, H. Treatment of domestic wastewater using the combination of porous concrete and phytoremediation for irrigation. Paddy Water Environ. 18, 729–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-020-00814-7 (2020).

Teymouri, E., Wong, K. S. & Pauzi, N. N. M. Iron slag pervious concrete for reducing urban runoff contamination. J. Build. Eng. 70, 106221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106221 (2023).

Teymouri, E., Wong, K. S., Tan, Y. Y. & Pauzi, N. N. M. Mechanical behaviour of adsorbent pervious concrete using iron slag and zeolite as coarse aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 388, 131720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131720 (2023).

Liang, X. et al. Removal effect on stormwater runoff pollution of porous concrete treated with nanometer titanium dioxide. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 73, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2019.06.001 (2019).

Albadarin, A. B. et al. Kinetic and thermodynamics of chromium ions adsorption onto low-cost dolomite adsorbent. Chem. Eng. J. 179, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.10.080 (2012).

Piol, M. N., Dickerman, C., Ardanza, M. P., Saralegui, A. & Boeykens, S. P. Simultaneous removal of chromate and phosphate using different operational combinations for their adsorption on dolomite and banana peel. J. Environ. Manage. 228, 112463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112463 (2021).

Khoshraftar, Z., Masoumi, H. & Ghaemi, A. An insight into the potential of dolomite powder as a sorbent in the elimination of heavy metals: A review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 7, 100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2022.100276 (2023).

Jamil, N. A. et al. Dolomite as a potential adsorbent in water treatment: pH, turbidity and Pb (II) removal studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 5669–5680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-05375-w (2024).

Amiri, M. J. Synthesis and optimization of spherical nZVI (20–60 nm) immobilized in bio-apatite-based material for efficient removal of phosphate: Box-Behnken design in a fixed-bed column. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 67751–67764 (2022).

Ezemagu, I. G., Ejimofor, M. I., Menkiti, M. C. & Nwobi-Okoye, C. C. Modeling and optimization of turbidity removal from produced water using response surface methodology and artificial neural network. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 35, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajce.2020.11.007 (2021).