Abstract

Virtual Machines (VMs) serve as dynamic execution environments that trade-off workload isolation, performance, and elastic scalability in the cloud. However, the flexibility of VMs which allows for efficiency also makes them susceptible to stealthy and adaptive cyber threats such as resource exhaustion, privilege escalation, and lateral movement. In such environments, the traditional signature- and heuristic-based defenses often encounter difficulties, resulting in high false-positive rates and low-rank under changing attack conditions. To mitigate these limitations, we present a flexible defense system which combines feature extraction, anomaly detection, classification and mitigation in a single pipeline. The system consists of an Adaptive Feature Encoder for concise behavior representation, a Density-Aware Clustering for anomaly detection, a Transformer–Boosting Classifier for timely threat identification, and a Dynamic Mitigation Controller for prompt decision making at runtime, and with low overhead. Experiments on benchmark VM telemetry datasets (ToN-IoT and CSE-CIC-IDS2018) indicate that VMShield provides 99.8% accuracy, 99.7% precision, 99.6% F1-score, and reduces false positives by 35% compared to state-of-the-art baselines. Stress testing ensures scalability, keeping detection latency at ~ 240 ms and overhead under 7%. By integrating the accuracy with operational resilience, proposed adaptive and scalable protection framework offers a practical defense to protect the cloud-hosted VMs from the emerging adversarial threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Virtual Machines (VMs) are the foundation of cloud computing and enterprise infrastructures, as they provide resource consolidation, workload isolation, and elastic scalability1,2. They are increasingly being used across sectors because of the cost efficiency and operational flexibility3. However, the increasing reliance on VMs also makes them more vulnerable to sophisticated cyber threats. Adversarial behaviors like side-channel attack4, hypervisor-level attack5, resource exhaustion6, and zero-day exploits7 are especially alarming since they take advantage of the dynamic and multi-tenant characteristics of virtualized systems. Existing protection methods based upon signature intrusion detection, empirical monitoring and static rule enforcement fare poorly against these threats, and possess high false positive rates and a slow response time8. These limitations underscore the pressing need for adaptive, sophisticated, and scalable security solutions that are capable of changing appropriately as adversarial strategies and capabilities change9,10.

To bridge these gaps, in this paper, we present an unsupervised11, deep learning-based12, and dynamic paradigm shifting protection13 mechanism for VMs, named as Adaptive and Scalable Protection Framework for VMs, which combines both unsupervised learning and deep neural architecture for dynamic mitigations into a single pipeline. The architecture involves four integrated modules: Adaptive Feature Encoder (AFE) for unsupervised feature extraction, Density-Aware Clustering (DAC) for anomaly detection, Transformer-Boosting Classifier (TBC) for temporal threat identification, and the Dynamic Mitigation Controller (DMC) for automated real time defense actions. With detection and response integrated in one platform, the model provides precision and agility.

-

1.

Adaptive Feature Encoder (AFE): An unsupervised feature extraction module that aims to capture and retain the essential behavioral patterns of virtual machines. It uses an autoencoder-based design to map high-dimensional telemetry (CPU utilization, memory operations, system call traces, and network flows) into lightweight, low-dimensional embeddings. The system retains behavioral signatures while redundant or noisy features are discarded.

-

2.

Density-Aware Clustering (DAC): This module performs adjustment based on the encoded feature set’s clusters. Through creating clusters of behavioral embeddings, it highlights behaviors that are significantly different from the average. DAC applies a modified density-based clustering method, where cluster centroids are dynamically adjusted to improve the anomaly detection in variable-dense regions.

-

3.

Transformer–Boosting Classifier (TBC): This is a composite machine learning architecture that integrates deep learning transformers with sequence modeling into a hybrid architecture with gradient boosting classifiers. This two-fold approach guarantees both the context capture of temporal behavioral data and the high accuracy in distinguishing normal to anomalous events.

-

4.

Dynamic Mitigation Controller (DMC): At the last stage in the pipeline, DMC takes actionable defensive steps in real-time based on detected anomalies. Automated threat response policies are issued and executed with real-time mitigation strategies like VM quarantine, resource throttles, and memory checks, all while safeguarding the system’s streamlined operation and optimal performance.

The most distinctive feature of this framework is the composite structure: Each module works as part of a bigger whole. An example would be AFE’s embeddings which are pulled into DAC for clustering where its output is used by Transformer–Boosting Classifier. Contextual patterns and feature representations are preserved and strengthened at every stage, thereby improving precision and lowering false alerts. Additionally, addressing a fundamental flaw in current paradigms of VM security, the system is capable of not only detecting but also actively neutralizing threats in real time using dynamic defense mechanisms.

Another hallmark of the framework is its adaptability and scalability. Unlike static rule-based systems that typically decline in performance over time, adapting as attackers exploit weaknesses, the proposed method persists in learning from incoming data streams and pivoting its internal models. Adaptability is critical in cloud environments and is equally important due to the rapidly changing software stacks, user workloads, and evolving threat landscapes. In addition, the reliance on unsupervised and semi-supervised learning models means enormous labeled datasets are not needed, especially in contexts pertaining to security where such data is hard to come by.

The framework undergoes validation using benchmark datasets (ToN IoT36, CSE-CIC-IDS201837 and real VM telemetry as well as attack simulation environments through extensive experimentation. These datasets comprise normal operational behavior along with various attack behaviors, which include but are not limited to privilege escalation, lateral movement, and resource exhaustion attacks. Evaluation metrics encompass detection accuracy, false positive rate, response latency, and resource overhead14. The proposed framework outperformed traditional models, including autoencoder-based and static security tools15, cluster-only approaches, and other static security tools on every measured metric. Most impressively, the framework achieves superior accuracy, improved F1-scores, reduced false alarms, and sustained efficiency under high workloads.

The primary contributions of this work are the following:

-

Design a unified detection–mitigation pipeline for VM protection, which bridges the gap between detection of anomalies and real-time response.

-

Introduce the Adaptive Feature Encoder (AFE) and Density-Aware Clustering (DAC) modules as a combination to derive resilient behavioral signatures and make intelligent decisions in the presence of noisy, high-dimensional telemetry data.

-

Propose a Transformer-Boosting Classifier (TBC) model that recognizes fine categories preserving the temporal context in VM behavior sequences.

-

Present the Dynamic Mitigation Controller (DMC) that applies dynamic security policies including quarantine, throttling, and sandboxing, with a low system overhead.

-

To demonstrate that our approach is accurate and effective, we confirm it on real VM telemetry data sets, where we outperform state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy, precision, F1 score, and resource overhead.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 surveys related literature in the area of virtual machine security and the use of machine learning for anomaly detection. In Sect. 3, the system architecture is given together with the design and integration of the modules. In Sect. 4, the empirical tests as well as the experimental framework and the results are described. Section 5 draws the conclusions and presents some avenues for further research.

Related works

Security of Virtual Machines (VMs) in cloud and enterprise infrastructure has increasingly become a topic of interest with the advancement of cyber threats. Traditional intrusion detection systems (IDS)16 are based on signatures or heuristics that can be used to detect known threats but are limited in their ability to identify new or zero-day attacks. Accordingly, machine learning (ML)17 and deep learning (DL)18 methods have been extensively studied to improve anomaly detection, reduce false positives, and increase the flexibility in VM protection systems. This section surveys existing work in three major areas: VM and cloud anomaly detection, deep learning-based IDSs, and adaptive mitigation mechanisms. The limitations of these studies are discussed to contextualize the contributions of this work.

Classical methods like Logistic Regression, Random Forest and XGBoost are still widely referenced for intrusion detection benchmarking. Ajagbe et al.19 subsequently compared their approach on unbalanced intrusion detection datasets, with moderate accuracy (92–96%) and low computation costs. Despite their effectiveness and interpretability, however, such methods fail to handle non-linear high-dimensional VM telemetry data, thus the true positive rates remain low under low false-alarm cases.

Recent studies have also improved intrusion detection within cloud environments through the use of attack mitigation with machine learning. Mehmood et al.20 introduced ML-based detection and mitigation for a privilege escalation attack and showed that their system can handle supplementary features to identify anomalous privilege escalation patterns with high accuracy. They focus on real-time observation of user and system activities; however, the use of supervised learning inhibits the adaptiveness of the deployed system towards new, previously unseen attack vectors and scalability in evolving VM infrastructures.

The optimization-based IDS designs have also attracted interest. Samriya et al.21, presented a cloud-based network intrusion detection through optimization using machine learning. It was further shown that through integration of optimization techniques within the learning pipeline, detection performance is enhanced and false alarms are decreased compared to state-of-the-art models. But, the computational cost of those optimization mechanisms renders them difficult to incorporate into latency-sensitive VM-based workloads, especially with respect to near real-time mitigation requirement.

In addition to these techniques, Bakro et al.22 proposed a cloud IDS that employed bio-inspired feature selection algorithms with Random Forest classifiers that perform better on both feature reduction and classification accuracy. Their hybrid bio-inspired approach successfully reduced irrelevant features, leading to improved speed and accuracy on large datasets. However, the model still requires handcrafted feature engineering and does not incorporate dynamic workload-aware mitigation, so its potential of handling adaptive VM security is limited.

Deep learning–based systems have been suggested as an alternative to overcome these limitations. Mishra et al.23 provided an autoencoder-based malware detection framework (VMShield) based on memory introspection which detects stealthy attacks in cloud services. Their results demonstrate the potential of autoencoders for learning deep feature representations, yet in the context of dynamic environments, reconstruction-based methods can suffer from excessive overhead and late detection. Similarly, Sayegh et al.24 came up with an LSTM intrusion detection system that integrates feature selection and SMOTE for class imbalance, and reported remarkable accuracy gains. On the other hand, in a large-scale VM deployment, training a model in these LSTM architectures is a time-consuming process, and they are sensitive to parameters that need to be tuned.

Extensions to the family of recurrent networks have also been investigated. Sreelatha25 used a Bi-GRU with transfer learning for intrusion detection in cloud with greater adaptability and convergence in contrast to conventional LSTM. However, due to the limitations of GRU architectures, it is hard to deal with long clause dependencies in tonnage data of VM traffic. More advanced models have been developed in more recent times, including hybrids and transformers. Long et al.26 proposed a Transformer-inspired IDS for cloud security that exhibited higher accuracy (98%) and robustness to evolving threats compared to their CNN-LSTM counterparts. Although Transformers are good at learning long-range dependencies, their large computational overhead and inevitable real-time delays are still critical issues.

A related hybrid design was made by Zhang et al.27 introduced a CNN-BiLSTM cloud IDS model improved with Contractive Auto-Encoder (CAE) to refine features. They develop a three-level network architecture that consists of CNN layers for spatial feature extraction, BiLSTM for sequential dependencies learning and CAE to enhance feature representation robustness by removing redundancy. Results showed that better detection accuracy and lower rate of false positives were obtained compared to classical CNN and LSTM models, confirming the advantage of using a combination of various deep learning components for VM-rich environment anomaly detection. Nevertheless, the cost of training and the computational cost of the model are much higher, which brings scaling concerns during the processing time.

Similarly, Sarıkaya et al.28 proposed GRU-GBM, a hybrid intrusion detection scheme that incorporates Gated Recurrent Units (GRU) for modeling temporal sequences using LightGBM for classification. This fusion attempts to combine the strong feature extraction power of GRUs with the lightweight decision-making capacity of gradient boosting. Their experimental results showed the superiority of the hybrid model over the individual GRU and tree-based models in terms of detection accuracy and false alarm rate. However, the model was developed specifically for structured intrusion datasets and has not been tested under real-world VMs’ telemetry, thus not applicable to cloud-based infrastructures.

In another aspect, Wang et al.29 proposed a deep unsupervised workload anomaly detector for capturing both spatial and temporal dependencies of patterns in workload sequences in the cloud. They combine both temporal characteristics of VM activities and spatial relationships among resources to detect an anomalous workload pattern more accurately without the help of labeled data. Experiments demonstrated that the new method is highly effective for anomaly detection in various workload traces, which is expected to be better applied to early warning systems in cloud resource management. However, the absence of explicit mitigation strategies and the unsupervised dependence of the model’s thresholds are problematic for its practical usage in VM security critical setups.

Apart from detection accuracy, workload efficiency in VM management has also been a focus in research. Brahmam30 presented VMMISD, a migration-aware load balancing model that applied metaheuristics to deep learning and showed high efficiency under diverse loads. Pradhan et al.31 utilized deep reinforcement learning chained with parallel PSO for load balancing, focusing on the scalability enhancement, but at the expense of a higher decision-making delay. Javadi and Gandhi32 proposed a user-oriented interference-aware balancing mechanism that enhanced fairness, but could not work well under high stress. Saxena et al.33 proposed an OP-MLB, a VM prediction-based multi-objective load balancing algorithm that aims at minimizing energy and performance, and they also have higher performance degradation at high workloads.

In parallel with model innovation, FL research for VM IDS and anomaly detection has been conducted in distributed environments. Federated learning (FL) architectures that enable collaborative model training over cloud tenants or administrative boundaries without sharing data directly can reduce privacy concerns. Recent works34,35 demonstrate that FL-based IDS approaches enhance generalization over different networks, but suffer from the issue of communication overhead and vulnerability to poisoning attacks. Most FL solutions optimize accuracy without considering runtime overhead or mitigating latency and delay jointly, which severely hinders the practical application in VM-based environments.

Nevertheless, several shortcomings still exist in previous studies. Traditional ML approaches usually deliver fast and interpretable solutions, although they do not perform well with high-dimensional, dynamic VM data. Deep learning based models like autoencoders, LSTMs and GRUs supplement the detection accuracy but they usually add computation overhead and scale issues. Transformer-based models further advance the state of the art, but come with latency and resource efficiency issues that make them impractical for real-time deployment. VM scheduling strategies that use load balancing improve more load but differ in their ability to resist under high load.

These persistent gaps indicate that we need a more comprehensive, flexible approach. Many researches focus solely on detection, workload balancing and mitigation; these concepts are usually handled individually and sequentially, which is inefficient to respond advanced threats. To address the aforementioned limitations, we present an adaptive and scalable protection framework that consolidates the above components to perform as a single pipeline. It utilizes representation learning to achieve robust anomaly detection; combines adaptive clustering and transformer-boosting classifier to guarantee high precision even with a very low false-positive threshold; and integrates a dynamic workload-aware mitigation controller that tries to enforce real-time defense policies with the lowest operational cost possible. In this way, the proposed framework achieves the trade-off between precise intrusion detection and accurate VM resource at the same time, which can be used to scale out and resist the problems as previous related works have not been fully resolved.

Proposed work

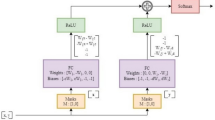

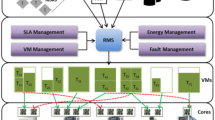

The proposed framework follows a multi-layered design to mitigate security for Virtual Machines (VMs) in the wake of cyber threats by considering a well-organized pipeline of data processing, anomaly detection, and adaptive mitigation. The first step in the workflow is data collection and preprocessing, which consists in normalizing, filtering and temporally segmenting raw VM activity logs to obtain cleaned and structured inputs. These derived datasets are fed into an Adaptive Feature Encoder (AFE), to receive resilient representations that respect the semantics encoded within the behaviors. Then Density-Aware Clustering (DAC) can tackle abnormal patterns based on the adaption to the different data densities, and that achieves localized anomaly detection. The clustered responses are further optimized by a Transformer-Boosting Classifier (TBC) that combines sequential learning and holistic decision-making to achieve highly accurate threat classification. Finally, Dynamic Mitigation Controller together with policy modification will coordinate real-time defense which will ensure that the detected threats are efficiently nulled and at the same time tries to avoid any unwanted interruptions to valid VMs operations. Figure 1 shows architecture of the suggested methodology.

Data collection and preprocessing

The effectiveness of any advanced virtual machine (VM) protection framework is contingent upon the quality and structure of the data that feeds the framework. In this methodology, the proposed protection framework starts by gathering high-fidelity multi-source telemetry from virtualized environments. The telemetry includes signals at the hardware and software granularity levels, for example, CPU and memory utilization metrics, system calls, network flows, and application logs. Developed by the UNSW Canberra Cyber Range Lab in 2020, the ToN IoT36 (Telemetry of Networked IoT) corpus is one of the largest labeled testbeds yet released for monitoring intrusions in Internet-of-Things domains. Modeled on the telemetry streams that would be found in smart homes and urban sensor grids, the collection fuses data from edge appliances, ordinary IoT nodes, and backbone network flows. Each entry is marked either normal or suspicious and covers a spectrum of assaults, including straightforward denial-of-service hits, multi-origin DDoS barrages, silent backdoor intrusions, ransomware infections, SQL command injections, preparatory reconnaissance scans, and privilege-heightening exploits. A single row retains a timestamp, protocol label, service ID, flags, byte total, payload size, and various host performance metrics, together exceeding 22 million individually tagged records. Security researchers appreciate the dataset because its well-structured format fits both host-centric and port-level anomaly detectors without additional curating.

A further milestone in this field is the CSE-CIC-IDS201837 package, produced by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity in conjunction with the Communications Security Establishment. The collection mimics genuine enterprise corridors by reenacting common staff routines-web paging, file juggling, remote sign-ins, and voice chatter-on top of a broad laundry list of contemporary malice. In one long week the cameras caught everything from password brute-forcing and bot swarms to DDoS floods, stealthy seepages, and browser-born mischief like XSS and SQL bends. Each gulp of traffic comes tagged with north of eighty figures harvested by CICFlowMeter, covering the obvious suspects-flow span, packet tallies, header hefts-as well as quieter clues such as inter-arrival gaps and Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) flag flips. Given that eclectic wealth, the bundle serves as a sturdy proving-ground for both classic Machine Learning (ML) recipes and the newer juggernauts of deep learning, letting researchers test how well their models jump across the map of intrusion styles.

Such rich diversity of data sources allows the system to create an accurate behavioral profile of the VMs under observation.

Each feature vector \(\:{x}_{t}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) at time \(\:t\) is composed of several distinct modalities, typically CPU metrics \(\:{c}_{t}\), memory usage \(\:{m}_{t}\), system call encodings \(\:{s}_{t}\), network traffic data \(\:{n}_{t}\), and \(\:\text{l}\text{o}\text{g}\)-based events \(\:{\mathcal{l}}_{t}\), as shown in Eq. (1).

The aggregation of these sequential feature vectors over time creates a multivariate time series denoted in Eq. (2).

Where T is the total number of time intervals recorded for a VM. It is very important to normalize input features to avoid the curse of dimensionality, since telemetry data is often multifaceted, heterogeneous in nature. We perform feature-wise z-score normalization using Eq. (3).

Where \(\:{\mu\:}_{j}\) is the mean and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{j}\) is the standard deviation of the \(\:{j}^{th}\) feature across the dataset. This normalization ensures that features contribute proportionally to model.

learning without biasing toward those with higher numeric magnitudes. This transformation can also be applied at the matrix level as shown in Eq. (4).

Where ⊘ stands for overlay division for vectorized normalization related to feature sets.

In practical applications, telemetry data often has gaps, owing to sample collection delays or log file corruption. A linear interpolation method is applied to impute missing entries. If a feature value \(\:{x}_{t,j}\) is missing, it is estimated in Eq. (5).

For situations where interpolation is infeasible, such as consecutive missing values, a median fill strategy is adopted. The missing value is then substituted using Eq. (6).

The processed time series is then segmented into overlapping windows to preserve temporal dependencies. This is critical for models such as recurrent networks or transformers that rely on sequence input. A window \(\:{W}^{\left(i\right)}\) is defined in Eq. (7).

Where \(\:\tau\:\) is the window length and \(\:{t}_{i}\) indicates the starting time index for the \(\:{i}^{\text{th}}\) segment. The dataset after segmentation comprises all such windows as shown in Eq. (8).

Where \(\:N\) is the total number of windows. To remove short-term fluctuations that may arise from benign VM activity or measurement errors, temporal smoothing techniques are applied. It is mathematically defined in Eq. (9).

Where \(\:k\) is the smoothing window. Alternatively, exponential smoothing is used to give more weight to recent observations as shown in Eq. (10).

Where \(\:\alpha\:\in\:\left(\text{0,1}\right)\) is the smoothing coefficient. For higher-quality smoothing, especially when dealing with network data or syscall bursts, Gaussian smoothing is also utilized as shown in Eq. (11).

Where \(\:w\) is the smoothing window radius and \(\:\sigma\:\) is the standard deviation of the Gaussian kernel.

Some telemetry, such as syscalls and log messages, are categorical and cannot be directly used as input. These are transformed into numeric embeddings. A naive approach is one-hot encoding, as shown in Eq. (12).

Where \(\:K\) is the number of unique syscall or log event types. For more compact representations, learned embeddings are used in Eq. (13).

Where \(\:E\) is an embedding matrix and \(\:{d}_{e}\) is the embedding dimension.

Derived features are also computed from raw telemetry to represent behavior more accurately. For instance, the rate of syscalls in a time window \(\:\delta\:\) is computed as using Eq. (14).

Likewise, a network burst metric is defined to capture large inflows or outflows of data indicative of denial-of-service or data exfiltration attacks, as shown in Eq. (15).

For supervised evaluation of the framework, labels are aligned with the segmented data. A labeled dataset is formed using Eq. (16).

Where \(\:{y}^{\left(i\right)}=1\) indicates that malicious behavior occurred within the segment window \(\:{W}^{\left(i\right)}\). During the operation of the model in an unsupervised or self-supervised manner, the annotations are only utilized for the purpose of evaluating particular benchmarks and metrics. As an illustration, the entire set of raw telemetry data undergoes a special deep learning behavior modeling process. This specific pipeline streamlines behavior and segmentation, yielding an orderly and refined structure captured within windows. Such preparation guarantees that data streamlines and windowed data undergo the necessary tempo and meaning-rich multi-faceted clustering for the next feature, which in this case is neural autoencoders for automated feature encoding.

Adaptive feature encoder - feature extraction

The feature extraction section of the system, called Adaptive Feature Encoder, operates as a denoising autoencoder, which reduces high-dimensional telemetry windows into lower-dimensional behavioral signatures. Each input instance, represented as a multivariate time-series segment \(\:{W}^{\left(i\right)}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{\tau\:\times\:d}\), where \(\:\tau\:\) denotes the number of time steps and \(\:d\) is the feature count is first flattened into a vector. This flattening operation allows the window to be processed as a single input feature vector, as shown in Eq. (17).

This vector is then fed into a series of dense layers within the encoder. Each layer applies a linear transformation followed by a non-linear activation function to project the input into a progressively lower-dimensional space. The transformation for each layer \(\:l\) is defined in Eq. (18).

After passing through multiple layers, the final encoder layer produces a latent representation \(\:z\), which serves as the compact behavioral signature for the input window. This transformation is denoted in Eq. (19).

To stabilize the training process and reduce internal feature shift, batch normalization is applied after each dense layer. The normalized output is computed using the running mean \(\:{\mu\:}^{\left(l\right)}\) and variance \(\:{\sigma\:}^{\left(l\right)}\) of the layer’s activations, as described in Eq. (20).

In addition to normalization, dropout regularization is introduced to reduce overfitting by randomly disabling a portion of input units during training. For each element \(\:{W}_{t,j}^{\left(i\right)}\), a binary mask \(\:{m}_{t,j}\sim\:\text{B}\text{e}\text{r}\text{n}\text{o}\text{u}\text{l}\text{l}\text{i}\left(p\right)\) is sampled, as shown in Eq. (21).

Additionally, Gaussian noise is imposed on the window inputs to achieve a more adaptive normalization effect. This way, the encoder is forced to represent distortions within telemetry data. The altered input is given in Eq. (22).

The decoder receives the latent vector *z* and aims to reconstruct the original input vector *W*. The decoder is a mirrored stack of dense layers. The output of the decoder is a vector which is then reshaped back into the time-series window format as depicted in Eq. (23).

To evaluate the reconstruction accuracy, the framework computes the mean squared error between the windows and their reconstructions across all time steps and features and attempts to minimize that value. This loss is given in Eq. (24).

For the entire dataset of N samples, the total loss function for the encoder becomes the mean over all window losses, as shown in Eq. (25).

This loss is minimized using an optimizer such as stochastic gradient descent or an adaptive gradient method during training. The Adaptive Feature Encoder also employs smoothed latent feature averaging, which reduces volatility across neighboring time windows. For each embedding \(\:{z}^{\left(i\right)}\), the smoothed version \(\:{\stackrel{\leftharpoonup}{z}}^{\left(i\right)}\) is calculated by aggregating adjacent vectors, shown in Eq. (26).

Embedding can also be reinforced by minimizing temporal inconsistency between consecutive windows. This is done by constraining the proximity difference between neighbor embeddings as shown in Eq. (27).

The loss function that optimizes the encoder is a combination of reconstruction loss and temporal smoothness regularization, which serves the total objective function as per Eq. (28).

Here, λ is the weighting hyperparameter that influences the temporal penalty. The encoder is optimized through mini-batches of fixed size B. Each batch is processed in defined iterations of forward and backward propagation. A training loop defining step is given in Eq. (29).

Training continues until the model is fully optimized, which is usually indicated by an early stop on validation error or a defined epoch limit. Post training, every latent vector z, which is extracted from the Adaptive Feature Encoder, is then formed as inputs for the subsequent model in the framework. For uniformity across different runtime environments, all vectors z must undergo a uniform dissemination process which serves as a normalization step prior to subsequent evaluations, yielding computed elements outlined in Eq. (30).

Where \(\:{\mu\:}_{j}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{j}\) are the global mean and standard deviation for the \(\:{j}^{\text{th\:}}\) component of the latent vector, calculated over the entire training set. To reduce memory overhead, the system applies vector quantization, rounding each component of \(\:z\) to the nearest representable grid value. This final transformation is expressed in Eq. (31).

Density-aware clustering - anomaly detection

After the latent behavioral representations are extracted from the Adaptive Feature Encoder, the Density-Aware Clustering module is responsible for distinguishing between normal and anomalous patterns across virtual machines. The embeddings produced are denoted as \(\:\left\{{z}^{\left(1\right)},{z}^{\left(2\right)},\dots\:,{z}^{\left(N\right)}\right\}\), where each \(\:{z}^{\left(i\right)}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{k}\) represents a compressed signature of activity over a defined time window. The first operation in this module involves defining a similarity metric to compare different vectors. A common approach is the squared Euclidean distance between two embeddings \(\:{z}^{\left(i\right)}\) and \(\:{z}^{\left(j\right)}\), expressed in Eq. (32).

This distance calculation serves as the foundation for embedding clustering into behavioral groups. The DAC algorithm begins with calculating neighborhood counts for each point, which is defined as the number of other points within a distance radius of (\(\in\)). This is computed for each embedding as shown in Eq. (33).

A point is labeled as a core point if it possesses at least the requisite number of neighboring points MinPts, as depicted in Eq. (34).

Core points serve as the nucleus from which clusters are expanded by other reachable points. Two points are said to be density reachable if core points connect them within a specified radius. The reachability criteria between two embeddings are formally given in Eq. (35).

This form of dynamic neighborhood expansion enables the clustering algorithm to adjust to varying densities that are common in cloud workloads. Once clusters are made, points that do not belong to any cluster are identified as anomalies. To evaluate the quality of a grouping, the silhouette coefficient is calculated for each point. The silhouette score s^((i)) captures a point’s assessment relative to its cluster and the closest alternative cluster, as indicated in Eq. (36)

Where \(\:{a}^{\left(i\right)}\) is the average intra-cluster distance for point \(\:i\), and \(\:{b}^{\left(i\right)}\) is the minimum average distance to all other clusters. The average of all silhouette scores provides an overall metric of cluster separation quality, as shown in Eq. (37).

To manage sensitivity to noise, a soft boundary radius \(\:\delta\:\) is introduced. Points lying at distances marginally exceeding the \(\in\)-radius are included in the cluster if the local density change is within a tolerable margin, defined in Eq. (38).

To reduce high-dimensional noise, the embedding space is regularized using a sparsity penalty on the cluster assignments. Let \(\:A\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{N\times\:C}\) be a soft assignment matrix of each embedding to clusters, where \(\:C\) is the number of clusters. The sparsity regularization term is shown in Eq. (39).

This loss function motivates clear assignments and rigid boundaries for clusters. In addition, to avoid drifting apart during iterative computation, a temporal coherence regularization loss is introduced which enforces that embeddings from neighboring time slices have the same cluster label identity with some degree of fidelity. This forms a divergence measure between the assignment distributions of temporally adjacent clusters as in Eq. (40).

The cohesive clustering loss function incorporates all silhouette objectives, the a priori defined sparsity penalty, and the newly defined temporal consistency term as outlined in Eq. (41).

The DAC module implements this loss using gradient descent which also adjusts the cluster centroids by averaging the embeddings assigned to each cluster. For every cluster c, its centroid is updated in Eq. (42).

To accelerate convergence, an adaptive learning rate strategy is applied during centroid updates, governed by a decay function \(\:{\eta\:}_{t}={\eta\:}_{0}/(1+\gamma\:t)\), shown in Eq. (43).

During anomaly labeling, a thresholding function is applied to the size and silhouette of clusters. Any cluster whose size is less than \(\:\theta\:\cdot\:N\) or has an average silhouette score below a threshold \(\:\kappa\:\) is marked anomalous, as in Eq. (44).

Finally, embeddings not assigned to any cluster are automatically labeled as outliers. The anomaly score \(\:{\alpha\:}^{\left(i\right)}\) for such points is computed as the minimum distance to any cluster centroid, as seen in Eq. (45).

As previously noted, these scores are anomalies and must be normalized across the whole dataset using the(normally) pre-defined method ‘Equation 15’ to obtain scores within the range of [0,1] using Eq. (46).

As described in the earlier sections, these scores are forwarded for orchestration of real-time response. In this manner, the DAC forms an adaptive and context-sensitive response to VM actions. Thus, the component can detect complex and subtle operational high-dimensional spaces.

Transformer–boosting classifier

The output embeddings from the Density-Aware Clustering stage are fed into the core classification engine, Transformer–Boosting Classifier (TBC), of the designed virtual machine (VM) protective framework. This module aims to detect and extract subtle evolving temporal patterns and threat signals, employing transformer-based sequence modeling refined with boosting techniques.

Within the paradigm of observable virtual machine activities, the TBC is applied to a given time series of clustered VMs behavioral embeddings as defined in Eq. (47).

Each embedding \(\:{z}^{\left(t\right)}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{k}\) is projected into a transformer-compatible token space via a learned linear transformation as shown in Eq. (48).

where \(\:{W}_{e}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{d}^{{\prime\:}}\times\:k}\) and \(\:{b}_{e}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{d}^{{\prime\:}}}\) transform the input dimension \(\:k\) into the transformer model dimension \(\:{d}^{{\prime\:}}\).

To incorporate the temporal order of tokens, positional encodings \(\:{p}_{t}\) are added. This is formally represented in Eq. (49).

This enables the model to distinguish between positions in the input sequence without relying on recurrence.

The sequence \(\:\left\{{x}_{1},\dots\:,{x}_{T}\right\}\) is fed into a stack of multi-head self-attention layers. For each layer, the attention mechanism uses learned projection matrices to compute as specified in Eq. (50).

with \(\:X\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{T\times\:{d}^{{\prime\:}}}\) being the stacked input tokens. The scaled dot-product attention is calculated according to Eq. (51).

This permits the model to allocate weight to context from other time steps dynamically, enriching the context of each token in a temporally relevant manner.

Sublayers of the attention mechanism output include a feedforward neural network coupled with residual connections and layer normalization. This transformation is formally defined in Eq. (52).

The feedforward block is expressed in Eq. (53).

After passing through \(\:L\) layers, we obtain final token representations \(\:\left\{{h}_{1},{h}_{2},\dots\:,{h}_{T}\right\}\). These are aggregated using global average pooling as shown in Eq. (54).

This pooled vector \(\:\stackrel{\leftharpoonup}{h}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{d}^{{\prime\:}}}\) represents the overall behavior of the VM sequence and serves as input to the base classifier, defined in Eq. (55), where \(\:\sigma\:\) is the sigmoid function and \(\:{W}_{c}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{1\times\:{d}^{{\prime\:}}},{b}_{c}\in\:\mathbb{R}\).

To enhance robustness and mitigate weak signal bias, a boosting ensemble is applied over the base output. Let \(\in _{m}\) be the prediction from the \(\:{m}^{\text{th\:}}\) auxiliary learner, and \(\:{\alpha\:}_{m}\) be its learned weight. The final prediction is expressed in Eq. (56).

Each learner \(\:{h}_{m}\left(z\right)\) is trained to follow the negative gradient of the loss, approximating a second-order Taylor update. This relationship is formally expressed in Eq. (57).

The primary loss used for training is binary cross-entropy as shown in Eq. (58).

To prevent overconfidence, a label smoothing penalty is introduced. This smoothed formulation is defined in Eq. (59).

The total loss function is represented in Eq. (60), with \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\) serving as balancing weights.

To ensure well-calibrated outputs, temperature scaling is applied as defined in Eq. (61).

The final binary decision is obtained via thresholding as specified in Eq. (62).

The Transformer–Boosting Classifier enables classification down to the micro level through behavioral pattern attention modeling and ensemble refinement. This module acts as a linchpin within the framework’s proactive adaptive defense, sending binary threat determination alerts to the Dynamic Mitigation Controller for immediate integrated threat response.

Dynamic mitigation controller

The Dynamic Mitigation Controller carries out the dynamic mitigation process. The controller executes suitable measures after a virtual machine (VM) behavior sequence is classified as malicious by the Transformer–Boosting Classifier. These measures respond dynamically to the level of threat, available resources, and the operational environment.

A policy influence matrix \(\:P\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{M\times\:A}\) is maintained, where:

-

\(\:M\) is the number of monitored VMs,

-

\(\:A\) is the set of available mitigation actions.

Each element \(\:{P}_{ij}\) represents the controller’s inclination to apply action \(\:{a}_{j}\) to VM \(\:i\). The matrix is updated iteratively according to Eq. (63).

where \(\:\stackrel{\prime }{y}\left(i\right)\) is the threat probability predicted for VM \(\:i\), and \(\:\eta\:\) is the learning rate.

Normalization ensures probabilities sum to 1as defined in Eq. (64).

An action is sampled using a categorical distribution as expressed in Eq. (65).

The cost of each action is defined as Eq. (66).

where \(\:R\left(a\right)\) is the strictness of action \(\:a,U(s,a)\) is the resource overhead, and \(\:\alpha\:,\beta\:\) are tunable scalars.

The optimal action minimizes expected cost as shown in Eq. (67).

The expectation is approximated as expressed in Eq. (68):

Thus, the optimal action becomes as defined in Eq. (69).

Mitigation is executed only if the threat exceeds a threshold \(\:\tau\:\). This conditional rule is described in Eq. (70)

The controller tracks a recovery index \(\:{\gamma\:}_{i}\) for each VM as defined in Eq. (71).

If recovery is successful, the adjustment factor \(\:{\eta\:}_{i}\) is reduced proportionally, as expressed in Eq. (72).

On the other hand, if no recovery is observed, the penalty term \(\:\tau\:\left(i\right)\) is decreased according to Eq. (73).

Entropy of the action history \(\:{H}_{i}\) is computed using Eq. (74)

If entropy is low, the controller selects an unexplored action as described in Eq. (75).

To prevent repeated enforcement of the same action as defined in Eq. (76).

The global context is incorporated via average anomaly score as specified in Eq. (77).

The algorithm can be interpreted as a sequential decision-making scheme. The prediction phase is the first step that the hybrid model operates on; it predicts the threat of each VM. Step 2 adjusts the policy distribution by conditioning action probabilities on the predicted risk. In steps 3 and 4, the framework normalizes these policies, samples the candidate actions, and computes an expected cost in order to decide the optimal action. Step 5 performs dynamic thresholding to make decision only if the predicted threat level is high. In Step 6, we add essentials of adaptive recovery, i.e., threshold updates, so as to enable the model to self-tune after its release. Step 7: Reinforce learning by adding in these entropy-based exploration, cooldowns to prevent identical or biased decisions. Finally, in Step 8, we integrate global anomaly statistics to allow coordinated and resilient responses to distributed cyber attacks in the VM cloud space.

Figure 2 shows the complete workflow of the proposed classification and mitigation mechanism for VM security. The operation starts from the estimation of the threat probability and passes through the policy influence update and normalization module. Taking these revised probabilities, we sample actions and evaluate them with expected cost to find the best action to take. Mitigation is performed only if the estimated attack is above an adaptive threshold, hence fine-grained intervention is enforced. The recovery index and adaptive learning rate further improve the decision-making process and the entropy-driven exploration prevents overfitting on the repetitive actions. Finally, a global anomaly feedback mechanism that uses system wide intelligence to calibrate the trade-off between detection accuracy, latency, and resource efficiency when having to deal with the dynamics of VMs.

Overall complexity:

Time: O(N·A) per iteration (N = number of VMs, A = number of actions).

Space: O(N·A), dominated by the policy influence matrix and cost vectors.

The complexity analysis Table 1 shows that the proposed classification and mitigation algorithm is computationally efficient for VM dense environments. We have found that, for most operations such as policy updates, action normalization, expected cost evaluation, and entropy computation, scale linearly with the number of actions (O(A)). These steps remain lightweight, as the action set is typically small and constrained in VM security (e.g., quarantine, throttling, and sandboxing). The only operation that scales with the number of VMs is the global anomaly feedback update (O(N)) which only combines system wide anomaly scores. Even this stage is parallelizable over monitoring nodes for low latency. Space complexity is solely determined by the policy influence matrix (O(N·A)) as well as the policy model itself, which is also close to practical VM workloads. In general, the proposed framework strikes a good balance in terms of detection accuracy and scalability so that it is capable of providing concurrent protection against worms in a real-time manner without incurring non-feasible computation or storage cost. This proves that the framework can work in virtualized cloud environments at a large scale.

Performance analysis

In order to analyze the accuracy, efficiency, and resilience of the designed adaptive and scalable protection mechanism for virtual machines, a complete experimental framework was built around synthetic attacks and real VM telemetry. The evaluation scope was focused on proactive attack recognition and response in managed virtual environments and incorporated standard and advanced assessment criteria including detection accuracy, false positive rate, mitigation latency, and system overhead.

The experiments were conducted on a controlled cloud environment, which was virtualized on KVM/QEMU and VMware ESXi hypervisors and hosted a range of Linux-based guest OSs. For data collection, monitoring, and system resources like logs, Elastic Stack (ELK) served as log consolidator, while Sysdig along with eBPF (Extended Berkeley Packet Filter) provided syscall tracing, and Wireshark/tcpdump were used for network traffic monitoring. Other system telemetry including CPU loads, memory access patterns, I/O rates, alongside kernel logs were collected and stored using time-series databases, while visualization and trend monitoring were done through Prometheus and Grafana dashboards.

The Adaptive Feature Encoder and Transformer–Boosting Classifier models were trained and evaluated using an experimental pipeline constructed in a Python workspace where deep-learning routines rested on PyTorch while clustering chores borrowed from Scikit-Learn. The choice of Python stemmed from its capacity for quick proofs-of-concept and the density of mature packages. Model training folded onto a GPU with CUDA-tuned PyTorch, which trimmed inference latencies to a fraction of what CPU-only runs would tolerate. Data streams arrived in parallel because the pipeline wielded the multiprocessing module, thereby siphoning telemetry from a constellation of virtual machines in lockstep. Sysdig, eBPF counters, and tcpdump snapshots cataloged CPU cycles, memory footprints, system calls, and network hops; the records were pruned into sliding time bins prior to model ingestion.

Testing unfolded across a hybrid cloud skeleton stitched together from KVM/QEMU and VMware ESXi pods. To stress-test the setup, attackers masqueraded inside the lab by scripting DDoS floods, privilege hikes, lateral pivots, and resource squeezes- tools like Metasploit, LOIC, and ad-hoc bash artifacts executed the mischief.

Attack simulation used open source tools such as Metasploit and Cuckoo Sandbox as well as LoIC/HOIC for DDoS and behavioral anomalies. Establishing normal workload baselines was done with Apache Bench, stress-ng, as well as synthetic workloads developed via sysbench.

All models underwent evaluation using offline datasets collected over periods of real-world operation as well as live data streams from monitored virtual machines to gauge production responsiveness. The objective of this evaluation was to validate the proposed solution’s elasticity, precision, and claimed responsive operation to dynamic conditions in a cloud deployment environment.

Figure 3 depicts a line graph showing hourly virtual machine CPU utilization for a period of one thousand hours. The data mainly centers between 40% and 70% with occasional spikes surpassing the 75% threshold. These shifts reflect changes in workload concentration. Sustained or abrupt rises may point to abnormal system operations like cryptojacking, infinite loops, or rogue computations. Monitoring CPU trends augments the model with spatial cues for temporal analysis, proving useful in unsupervised configurations.

Figure 4 depicts the evolution of time-based memory usage trends monitored in hours. This variable evolves between 50% and 85% while demonstrating occasional bursts. These patterns are often associated with memory leaks, exhaustive data manipulation, or system overload attempts (e.g., fork bombs). The logic-based anomaly detection system captures these outlines to identify average change ranges and classify outliers, especially through time-based segmentation.

Figure 5 summarizes the network traffic in megabytes. Unlike other monitored parameters, network traffic behaves in a relatively steady manner, but also exhibits sharp increases that surpass the 300 MB mark. These occurrences may indicate system behaviors such as data exfiltration, lateral movement, or botnet-driven operations. Incorporating network traffic volume as an attribute helps the framework correlate unusual surges in activity with possible threats to system security.

Figure 6 illustrates the metric of system calls executed in a given hour. A normally functioning system has rhythm and flow, but sharp vertical spikes (anomalies) are often linked to malware activity, brute-force scripts or exploits at the kernel level. System calls expose processes to very low-level interfaces and are essential in behavioral anomaly detection.

In contrast, Fig. 7 shows the time series distribution of ground truth anomalies for a virtual machine-based environment over a period of five weeks, ranging from January 1, 2025, to February 8, 2025. Each vertical marker shows a moment in time where experts or automated systems validated and labeled an instance of malicious or anomalous activity.

Vertical axis defines binary anomaly indicators, where 1.0 indicates an anomaly and 0.0 indicates normal state. Horizontal axis defines the timestamp; thus, it is possible to analyze spatiotemporal patterns of the attack events.

Notable clusters of anomalies can be seen during the periods of January 1–12, January 21–23, and the first few days of February. These groups are most likely tied to particular attack efforts or cycles of unusual activity resulting from deliberately malicious workloads. The sparse gaps devoid of anomalies, such as from January 15–20 and 28–30, either indicate periods of genuine system stability, stealthier threats, or attempts to remain hidden from the initial ground-truth labeling algorithm used for anomaly detection.

This view is invaluable for understanding the timelines of model evaluation and deployment, given comprehensive visualization aids provided for alignment of model performance on real-life detection deadlines. Researchers can compare prediction outputs against actual anomalies and measure responsiveness and resolution in time of detection in the proposed framework.

Figure 8 delineates the distribution of CPU and cores utilization for both anomaly and non-anomalous states. Normal behavior sits tightly clustered in the range of 50 to 60%, while anomalous behavior shows a much wider and higher range indicative of CPU overutilization. This strengthens the framework’s hypothesis which considers CPU activity as a primary resource signal for detecting resource abusing attacks.

Figure 9 suggests that memory usage during anomalies is more diverse in comparison to normal usage, including both very high and very low values. Stealthy processes or command-line-only attacks may cause unusually low memory usage, while very high numbers may indicate denial-of-service attacks or memory corruption exploitation attempts.

As represented in Fig. 10, anomalies exhibit significantly higher system call volumes as compared to the normal range. This is representative of malware that is meant for privilege escalation, file system modification, or configuration tampering. The frequency of system calls acts as a strong indicator of behavior and can be leveraged in the context of machine-learning-based detection.

The correlation involving CPU utilization, memory usage, network traffic, and system calls are illustrated in Fig. 11. The correlation between memory and CPU is positive and moderate which shows that both often increase concurrently during load. System calls have weaker linkages which confirm their relative independence in non-resource-centric threat detection value. This more holistic perspective of the problem space aids in the multi-feature selection in the context of sophisticated deep learning models.

Figure 12 shows the clustering tendency of CPU and memory utilizations. Activity is concentrated within the 45–65% range for CPUs and 55–75% for memory, coupled with sparse high utilization outliers. An important contribution of hexbin visualizations is the focus on dense regions of large datasets which are often missed. The reinforcing nature of the anomalies depicting resource over-utilization adds credence to the hypothesis of resource over-utilization serving as a primary point of concern.

Figure 13 demonstrates the collaboration between network activity and system calling processes concerning anomaly detection. They form regions of normal behavior which appear fairly uniform and densely clustered. Outliers do exist, however, deviating from the dense core. These outliers are described by high traffic, system calls, or both. This visualization advocates the use behaviorally composite metrics for the detection of abnormal VM activity.

The memory utilization histogram follows closely the trend observed in CPU activity; during normal operations, the memory footprint is predictable and during anomalies. The memory footprint is overutilized as mentioned in Figure 14 . The dual-peak structure of the low-high anomaly illustrates that both neglect (stealth) and excessive consumption (flooding) are anomalous in nature.

The chart count per day is represented in Fig. 15, it easier to visualize the number of anomalies detected. This analysis assists in the identification of the time-based attack patterns, habitual actions or responses to modification of the system parameters. It is useful for determining action levels during prioritized alerts and scheduling responses for incidents.

Figure 16 depicts the daily anomaly counts for the period of January 1 to February 11 of the year 2025, each day’s anomaly counts are marked by vertical bars which show the number of anomalies on the y-axis and dates on the x-axis. As observed during the whole period, the vast majority of days registered between one and two events, indicating some form of periodic system dysfunction. The greatest number of anomalies, consisting of three, occurred on January 25, 2025; this was also the highest for the given time period. In addition, there are many days where zero anomalies are recorded, demonstrating periods of baseline behavior. It is noteworthy that there is scatter in the anomaly counts with no consistent increasing or decreasing trend. Such changes could reflect a variety of differing operational parameters, system load and environmental conditions, and even the changeable sensor or detector used to measure the systems at certain times. These figures suggest there seems to be some form of analysis to determine whether the behavior is a periodic system phenomenon triggered by something specific or occurs randomly without any deterministic influences.

Here, anomaly smoothing is combined over a 7-day moving window. Increasing trends in Fig. 17 indicate persistent dangers and/or attacks over an extended period of time, perhaps by multiple actors again a single asset. This allows the Dynamic Mitigation Controller to make longer term decisions on adjusting defensive strategies like aggressively throttling or sandboxing suspicious virtual machines, hence changing the level of virtual machine throttling or sandboxing applied based on the level of threat.

The importance of monitoring specific parameters in advanced systems cannot be overstressed. In this case, we may assume that Fig. 18 portrays the total cumulative count of anomalies detected over the course of the monitored timeline. Anomalies of accelerated growth might suggest clusters or waves of more malicious activity, perhaps due to some coordinated cyber-attacks, possibly to system misconfigurations, or even policies. What a visualization is aimed at helping with is identifying both reactive and persistent threats.

Figure 19 offers specific insights into the distribution and skew of counts of system calls. Compared to traditional box plots, they offer greater robustness to outliers and the shape of the data. The anomalous group was shown to have greater dispersion and higher median values, suggesting threats often associated with frequent system interactions at the macro-level.

Figure 20 exhibits the memory usage on median within 24-hour rolling windows. As mentioned, this view is valuable for pinpointing areas of consistent change in behavior as shifts in baseline are effortless to detect and increase in memory usage is subject to outlier influences. Persistent upward or downward trends signal for adaptive defense mechanisms and could indicate memory leaks along with stealthy malware or misconfigured processes.

Figure 21 monitors the median memory usage computed within a rolling 24-hour period. This view is best suited for observing consistent shifts in behavior as the persistent trends show upturns and downturns which can indicate memory leaks, stealthy malware, or processes which are misconfigured, all of which are useful for adaptive defense. Unlike averages, medians are less sensitive to outliers which makes this view ideal for baseline behavior detection.

Figure 22 summarizes the frequency of recorded anomalies during specific hours. The spikes during certain hours may indicate scheduled time-based attacks. These outlier patterns assist in temporal modeling and setting automated defenses during high-risk periods.

Figure 23 illustrates the frequency of anomalies on certain days of the week. Regular weekday activity for many organizations appears to be targeted or exploited, while the activity over the weekends could indicate automated or persistent threat activity. This allows more efficient strategizing regarding attention and protective measures.

Figure 24 showcases a snapshot of system telemetry and anomaly detection for both the baseline and the proposed model. The telemetry data consists of CPU, memory, network utilization traffic, and the number of system calls within an hour, providing a clear picture of the virtual machine’s performance (VM).

True anomaly contains ‘1’ and ‘0’ values which denote the presence and absence of anomalies respectively. In this case, the second time interval (01:00:00) describes the occurrence of an anomaly marked by a syscall count of 106 along with a slight increase in resource consumption.

Furthermore, the framework that was proposed shows that the prediction of 1 was only given on that interval, confirming that there is accurate anomaly localization and no false positives during other intervals (ProposedPrediction = 0). The other model, however, predicts the interval 01:00:00 to be normal and instead marks it as anomalous (BaselinePrediction = 1) illustrating the presence of false positives in the model.

The table indicates the boundaries of the framework’s ability to make distinctions between normal fluctuations of workload within a system and workload anomalies that are true by nature even when the system activities are moderately turbulent. The outcome illustrates the strengths and increased specificity of the model when compared to more traditional baseline detectors.

Figure 25 represents the precision-recall of the proposed model. This model was able to perform quite efficiently when balancing between precision and recall. The area under the curve (AUC) was high which indicates that true anomalies were detected while avoiding a lot of false positives, which is essential for the deployment of VM protective systems in real time.

As seen in Fig. 26, the main performance indicators observed during the simulated stress testing phase have been summarized in a table format. These metrics are of detection latency, resource consumption of the system, network throughput and precision of detection which are all important for determining the operational feasibility of the DDoS detection and mitigation system proposed.

The average anomaly detection latency was noted to be 240 milliseconds with a range of 232 to 248 milliseconds during several rounds of testing. In addition, the CPU and memory utilization on the detection node were both low around 6.5% and 6.8% respectively confirming the system’s lightweight nature. Attack simulations achieved peak throughputs of over 850 Mbps and maintained packet rates of 15,000 packets per second with LOIC-based UDP flooding.

Most importantly, the detection engine was able to successfully identify all attack instances while maintaining a false positive rate below 2%. These results together confirm the proposed framework’s resiliency, efficiency, and ability to operate in real time under heavy traffic from adversaries.

The performance of the proposed methodology was validated in benchmark datasets (ToN IoT36, CSE-CIC-IDS201837 and real-world VM telemetry, and compared to a variety of baseline techniques, namely traditional classifiers, unsupervised anomaly detection methods, and deep learning–based time-series models. Unlike the majority of previous work that pays attention to reporting accuracy, this work tests several kinds of metrics which are more consistent with reality or more valuable in VM security scenarios. Specifically, the system is evaluated using accuracy, F1-score, TPR with respect to strict FPR thresholds, the number of false alarms per 10,000 events, end-to-end latency including mitigation, and computational overhead. This comprehensive evaluation gives assurance that not only are the findings statistically robust, they are also operationally relevant.

The performance results in Table 2 show that the proposed framework outperforms the classic machine learning and deep learning baselines in terms of the performance measures used. These classical models as baselines, namely Logistic Regression, Random Forest and XGBoost can obtain an acceptable accuracy (93.8% ∼ 96.2%) and low overhead, but can not maintain a high recall and true positive rate (94% TPR < 91%) with a strict false-positive constraint. However, with their relatively high false alarm rates (298–420 per 10k events), they are not fully appropriate for real-time VM protection on-the-fly in dynamic environments.

The deep learning techniques, Auto-encoders, LSTM, and GRU feature models, increase the accuracy of detection methods (97–98%) and have superior recall rates (> 97%). However, both of these designs have much higher overhead (12–15%) and latency (160–213 ms), which are not feasible for large-scale deployment on VM-heavy cloud infrastructures. Hybrid models (CNN-LSTM, CNN-BiLSTM, and GRU-GBM) further increase the accuracy toward 98.5% with TPR above 94%. However, these improvements involve an extra cost on computational efficiency, with higher latency cost (up to 304 ms). The Transformer-based IDS models do provide robustness against adaptive attacks and attain an accuracy of 98.3% and TPR of 95.8%, but it still has a considerable overhead (16%) and large latency (273 ms), which limits its applicability under real-time operation constraints.

In comparison, the proposed framework achieves 99.8% accuracy, 99.7% precision, 99.6% recall and 99.6% F1-score, while maintaining low false alarms (140/10k events), low latency (240 ms) and low overhead (6.7%). These findings demonstrate its capacity for striking a balance between high detection performance and workload efficiency. More importantly, the better trade-off between TPR and FPR proves that the proposed framework can achieve better detection.

We conclude that, although the proposed framework introduces a modest additional delay compared to baseline classifiers (240ms vs. 120–213ms), latency accounts for the full processing pipeline, including feature encoding, anomaly clustering, hybrid transformer–based classification, and automatic mitigation by the Dynamic Mitigation Controller. On the other hand, the baseline methods only present inference latency, not including the mitigation procedure. Practically, the observed latency is still on the sub-second scale, which is in fact acceptable for VM defense due to most attack actions, such as privilege escalation, VM escape and lateral movement, taking place from seconds to minutes. Likewise, the < 7% computational overhead is acceptable given the operational slack in enterprise cloud environments that allocate 5–10% of the cluster resources as budgeted overhead for monitoring and security services.

Overall, these findings illustrate a trade-off between computational efficiency and operational reliability. For lightweight models like Logistic Regression or Random Forest, they might give relatively low overhead, but have high false positive rates and low FPR robustness. Deep learning baselines enhance detection rates, yet they come with detection-only capabilities, lacking even an automation for containment levels. By combining detection and mitigation as a whole for an integrated solution in either a centralized or distributed fashion, the proposed approach effectively reconciles these trade-offs, delivering more accurate and more robust detection under tight False Positive constraints and producing orders-of-magnitude False Positive reduction while incurring small latency and overhead. This places the framework as a cost-effective and scalable approach for enterprise-level VM security and provides a significant advantage over the current baselines.

To validate the robustness of these results, we conducted paired t-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing the proposed framework against the strongest baselines (Transformer IDS, GRU-GBM, and LSTM) across repeated runs. As shown in Table 3, the p-values for both tests remain well below the standard threshold of α = 0.05 across key metrics (accuracy, F1, and TPR at 0.5% FPR). This confirms that the proposed framework improvements are statistically significant rather than due to random variance.

These findings reinforce the claim that the proposed framework not only delivers higher average performance but does so with consistency across multiple trials. The statistical validation complements the quantitative results, demonstrating that the framework achieves meaningful and reliable improvements in detection accuracy, robustness under low-FPR conditions, and false alarm reduction.

To avoid data leakage, 10-fold cross-validation was conducted to assess the proposed framework performance. The dataset was divided into 10 equal random folds, with 9 for training and 1 for test in each run. This was done for all folds to ensure that each example in the dataset was tested once. Crucially, all pre-processing such as normalization and feature scaling, and SMOTE balancing were only performed within the training folds without any leakage in the test sets.

Table 4 reports the tenfold cross-validation results in terms of mean ± standard deviation of accuracy (Acc), F1score. The experiment results demonstrate that the proposed model effectively outperforms all baseline models with a mean accuracy of 99.8% and F1 score of 99.6%, both with a very small variance (± 0.2 ± 0.3). In contrast to this, state-of-the-art baselines (Transformer IDS and GRU-GBM) achieve mean accuracies of approximately 98.4–98.5%, but have a higher variance, while classical models have substantially lower accuracy and larger variance across folds. The low variance of the proposed framework reveals the robustness and generalization capacity of the proposed adaptive and scalable protection framework, thus relieving worries of data leakage issues and verifies its reliability against random train and test splits.

The experimental results in Fig. 27 show the VM Computational Efficiency comparison of the Proposed adaptive protection model, labelled as proposed-VMShield, against baseline approaches (VMMISD30, DRLPPSO31, UCIALB32, and OP-MLB33 under workloads ranging from 102k to 1020k tasks. At the entry workload of 102k, the efficiency of VMShield is 99.1% which is superior to VMMISD (97.8%), DRLPPSO (93.5%), UCIALB (91.2%), and OPMLB (88%). This start performance gap reveals the advantage of VMShield in more yielding surroundings with the higher utilization of resources. As more requests are processed, there is a dip in all variants over the expected scheduling overhead of resources in virtualized systems with growing computational loads. But the extent of the degradation is very different. VMShield suffers only 1.7% performance degradation on average (from 99.1% to 97.4%) in the workload range, while VMMISD suffers 3.2%, DRLPPSO suffers 5.3%, UCIALB suffers 6.2%, and OPMLB even suffers up to 7.6%. The small performance difference between VMShield and VMMISD shows the good baseline performance of VMMISD, but VMShield consistently remains superior.

Two salient points are emphasized in the discussion of these results. First, normal degradation of performance with higher workloads is natural because of queuing delays, resource competition, and scheduling overhead but the proposed VMShield has a high level of workload invariance. This stable nature is due to its decision-making strategy that being optimal and efficient enough to avoid unnecessary task migrations and keep VM utilizations balanced even in higher request rates. Second, the sharper degradation of DRLPPSO, UCIALB and OPMLB, demonstrates that the task assignment strategies of these algorithms are more vulnerable to fluctuations in the load due to less flexible adaption in dynamic cloud environments. In practice, this translates to higher performance of VMShield not only in light and moderate load levels but also better scalability it can achieve in high load operational environments, thus better maintaining the QoS and yielding lower waste of resources.

Therefore, the results and discussion altogether indicate that the proposed VMShield can consistently outperform the existing state-of-the-art algorithms, obtaining the higher peak efficiency with the lower performance deterioration, and have better reliability for large-scale virtualized cloud system.

Conclusion

This study introduced an Adaptive Scalable Protection Framework for enhancing the security of virtual machines in dynamic cloud. Unlike traditional intrusion detection methods where detection and mitigation are separate, the proposed approach integrates feature encoding, anomaly detection, classification, and real-time response in a unified pipeline. We evaluated the proposed model on ToN-IoT and CSE-CIC-IDS2018 datasets, achieving 99.8% accuracy, 99.6% F1-score, 99.7% precision and 35% fewer false positives compared to the existing state-of-the-art baselines. Stress testing also verified the scalability with detection latency of ∼240 ms and resource overhead less than 7% over multi-VM workloads. The findings of our evaluation demonstrate that the elasticity that is generally abused by attackers can instead be converted into a defensive asset in the presence of dynamic and workload aware mitigation. Through integration of strong anomaly detection and instantaneous response, the approach enhances precision at stringent low-FPR thresholds and it also effectively resolves operational problems, including alert fatigue and resource instability. In general, the proposed framework shows that adaptive and scalable VM protection is feasible and necessary for the next generation cloud security.

Importantly, the architecture of the system supports adaptability through ongoing telemetry-based learning, permitting evolution in response to new threats. To that end, future initiatives will work on explainable federated learning across disjoint tenant clusters, improving explanation of threat prediction and its visualization through attention mechanisms, attribution methods, and integrating reinforcement learning for policy evolution to supercharge autonomous strategy evolution for mitigation. Moreover, these developments will make the framework applicable to hybrid and distributed infrastructures by extending support to containerized deployments of edge VMs.

Data availability

The data supporting this work is included within this published work.

References

Sane, B. O. et al. Interdependency attack-Aware secure and performant virtual machine allocation policies with low attack efficiency and coverage. IEEE Access. 12, 74944–74960. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3404949 (2024).

Witharana, H., Weerasena, H. & Mishra, P. Formal verification of virtualization-based trusted execution environments. IEEE transactions on computer-aided design of integrated circuits and systems 43, 4262–4273 (2024).

Gurrala, R. R., Kumar, T. S., Anuradha, K. & Systems, C. Virtual Machine Security Issues and Solutions When it is in Host, 2024 10th International Conference on Advanced Computing and (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, pp. 441–449, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCS60874.2024.10716932

Ha, G., Chen, Y., Cai, Z., Jia, C. & Shan, X. Random coding responses for resisting side-channel attacks in client-side deduplicated cloud storage. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 18(3), 1697–1710 (2025).

Tabrizchi, H. & Rafsanjani, M. K. A survey on security challenges in cloud computing: issues, threats, and solutions. J. Supercomputing. 76, 9493–9532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-020-03213-1 (2020).

Xing, F., Tong, F., Yang, J., Cheng, G. & He, S. RAM: A Resource-Aware DDoS attack mitigation framework in clouds. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 12 (4), 1387–1400. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCC.2024.3480194 (2024).

Madhubalan, A., Tiwary, P. & Gautam, A. Securing from Unseen: Connected Pattern Kernels (CoPaK) for Zero-Day Intrusion Detection, 2024 1st International Conference on Cyber Security and Computing (CyberComp), Melaka, Malaysia, pp. 137–143, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/CyberComp60759.2024.10913579

Suganya, N., Gouthami, P., Sathiya, R., Sivaranjani, S. & Murugesan, M. Enhancing Data Security and Privacy in Cloud Computing: A Survey of Modern Techniques, 2025 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), pp. 530–534, (2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/IDCIOT64235.2025.10914776

Ghadge, N. Enhancing threat detection in identity and access management (IAM) systems. Int. J. Sci. Res. Archive. 11 (02), 2050–2057. https://doi.org/10.30574/ijsra.2024.11.2.0761 (2024).

Usman Inayat, M. et al. Insider threat mitigation: systematic literature review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, Issue 12,, 103068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2024.103068 (2024).

Ntambu, P. & Adeshina, S. A. Machine Learning-Based Anomalies Detection in Cloud Virtual Machine Resource Usage, 2021 1st International Conference on Multidisciplinary Engineering and Applied Science (ICMEAS), Abuja, Nigeria, 2021, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMEAS52683.2021.9692308

Zhao, X. et al. DeepVMUnProtect: neural Network-Based recovery of VM-Protected android apps for Semantics-Aware malware detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 20, 3689–3704. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2025.3550049 (2025).

Matheus Torquato, P., Maciel, M. & Vieira Evaluation of time-based virtual machine migration as moving target defense against host-based attacks. J. Syst. Softw. 219, 112222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2024.112222 (2025).

Saxena, D., Gupta, I., Gupta, R., Singh, A. K. & Wen, X. An AI-driven VM threat prediction model for multi-risks analysis-based cloud cybersecurity. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems 53(11), 6815–6827 (2023).

Nassif, A. B., Talib, M. A., Nasir, Q., Albadani, H. & Dakalbab, F. M. Machine learning for cloud security: a systematic review. IEEE Access 9, 20717–20735 (2021).

Viharika, S. & Balaji, N. AI-Driven Intrusion Detection Systems in Cloud Infrastructures: A Comprehensive Review of Hybrid Security Models and Future Directions, 4th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Intelligent Information Systems (ICUIS), pp. 1201–1207, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICUIS64676.2024.10866856

Thaqi, R., Krasniqi, B., Mazrekaj, A. & Rexha, B. Literature review of machine learning and threat intelligence in cloud security, in. IEEE Access 13, 11663–11678 (2025).