Abstract

Genetic variation is partly responsible for variability in drug response across populations. However, the full catalogue of pharmacogenetic variants and their distribution are yet to be established, thus posing challenges in implementing individualised medicine in understudied populations. This study aimed to characterise variation in key drug response genes across founder populations from the Northern Isles of Scotland. We analysed whole genome sequence datasets from 498 Shetlanders and 1372 Orcadians, the majority of whom are research participants in the Viking Genes programme, and compared the genetic variation in 41 selected pharmacogenes with observed distributions in other European datasets. From this gene-set, we present frequencies of known and potentially novel star alleles (haplotypes and structural variants) for 18 core pharmacogenes analysed using StellarPGx, and variant distributions in 23 other selected pharmacogenes with existing clinical annotations in ClinPGx (https://www.clinpgx.org). Despite important differences in the frequencies of rare and/or novel potentially high-impact variants, the distributions of the well-studied common actionable pharmacogene star alleles do not vary dramatically across Shetland, Orkney, and the European populations represented in the 1000 Genomes Project or allele frequency meta-analyses in ClinPGx. Importantly, for gene-drug pairs with Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines, we estimated (based on diplotypes alone) that the proportion of participants in the combined dataset that may benefit from a change in dose/drug ranged from 0 to 50.5%, depending on the gene-drug pair. Overall, understanding the landscape of pharmacogenomic variation in Shetland and Orkney is an important step towards implementation of precision medicine across rural Scotland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pharmacogenomics (PGx), an important facet of precision medicine, entails characterising the relationship between genetic variation across multiple genes and drug response. Several genetic variants have been associated with decreased efficacy of standard drug dosage regimens or increased risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) especially in genes encoding proteins involved in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of drugs, drug target genes, and modifier genes (such as G6PD, POR, and VKORC1)1,2,3,4,5,6. This has driven several research efforts towards supporting the implementation of genotype-guided therapy across clinical settings globally, but predominantly in Europe and North America7,8,9. Over the last decade, the feasibility of PGx has been enhanced in part due to the drop in sequencing costs and the ever-expanding technological capacity for genomic variant discovery. It is well-documented that the distribution of clinically actionable PGx variants can vary within and between populations10,11,12. Population-specific characterisation of the distribution of PGx variants or haplotypes across populations can therefore inform the prioritisation of gene-drug pairs and/or key variants for PGx testing.

Previous research has shown that isolated populations in the northern Isles of Scotland (Shetland and Orkney) tend to have genetic divergence compared to the mainland Scotland population and other populations represented in the UK Biobank, due to strong genetic drift13,14. Remarkably, pathogenic variants that are otherwise ultra-rare have been observed at increased frequencies in these isolates, across medically relevant genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA215,16. These findings are based on analysis of datasets from volunteers in the Viking Genes programme (https://viking.ed.ac.uk). This research is already informing various strategies for disease diagnosis in the Isles, complemented by other aspects such as return of genomic findings16,17. However, genetic variation that can impact drug response has not yet been investigated across the Viking Genes study populations. We therefore aimed to leverage the existing data from these cohorts to characterise variation in 33 Very Important Pharmacogenes (VIPs; https://www.clinpgx.org/vips) and eight other pharmacogenes with existing, though much lesser, evidence of PGx importance collated by the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB — now integrated into ClinPGx: https://www.clinpgx.org). We hypothesised that there were likely differences in the landscape of PGx variation in Shetland and Orkney populations compared to the mainland Scotland population, and other European populations.

The 33 VIPs, in particular, have substantial evidence to support the importance of these genes in PGx12. VIP gene families, such as the cytochrome P450 gene family, N-acetyltransferases, glucuronidases, and solute carriers, are known to harbour considerable genetic variation, with haplotypes and/or structural variants typically represented using the star allele nomenclature18,19. Here we report the distribution of both clinically actionable and unannotated variation across 41 pharmacogenes in Shetland and Orkney populations, compared to the variation observed in European populations (N=503) represented in the 1000 Genomes Project datasets20, and those represented in the ClinPGx reference materials (aggregate data from multiple studies). Importantly, understanding the distribution of known, rare, and novel PGx variation across the Isles is relevant for PGx testing strategies with a view towards potential genetics-guided treatment optimisation interventions.

Methods

Ethics statement

This research is a substudy under Viking Genes (viking.ed.ac.uk), a research programme with participants from the Viking Health Study—Shetland (VIKING I) and the Orkney Complex Disease Study (ORCADES). All the VIKING I and ORCADES participants gave written informed consent for broad ranging health and ancestry research including whole genome/exome sequencing.

VIKING I was approved by the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref 12/SS/0151). ORCADES was given a favourable opinion by Research Ethics Committees in Orkney, Aberdeen (North of Scotland REC), and South East Scotland REC, NHS Lothian (reference: 12/SS/0151). Both cohorts are now part of Viking Genes, with a favourable opinion from NHS Lothian South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee (reference 19/SS/0104).

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study participants

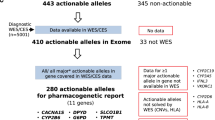

Figure 1 provides a general overview of the study outline. The study included participants from the Viking Health Study - Shetland (VIKING I)17 and the Orkney Complex Disease Study (ORCADES)21, which are family-based, cross-sectional studies aiming to identify genetic factors influencing complex disease risk in the population isolates of the Shetland and Orkney Isles in northern Scotland. These studies, along with VIKING II, are part of the Viking Genes programme (https://www.ed.ac.uk/viking). A detailed description of Viking Genes has been published in previous work13,14,17,21. For the pharmacogenomics analysis in this study, we included individuals for whom whole genome sequence (WGS) data is available, i.e. 498 participants from the Shetland archipelago via the Scottish Genomes Partnership22 and 1360 from Orkney sequenced at the Wellcome Sanger Institute23. From a WGS perspective, the average read depth across the Shetland WGS data was >30x, while the read depth across the Orkney WGS datasets was generally lower (interquartile range 15-20x). For allele frequency comparisons with other European populations, we recalled star alleles from the 30x WGS data of the 503 European-ancestry participants in the 1000 Genomes Project (1000G European participants)20, and we also used allele frequency data aggregated by ClinPGx from several previous studies (https://www.clinpgx.org/page/pgxGeneRef). Of the 1000G European participants, 24 are Orcadian; therefore, we removed them from the 1000G European group—remaining with 479 participants. Of the 24 Orcadian participants, 12 were already overlapping with the existing Orkney WGS dataset—we added the other 12 to this dataset to bring the total number of Orcadian participants in the study to 1372.

Overview of the study design and outline. Viking Genes is a project including cross-sectional studies aiming to identify genetic factors influencing complex disease risk in the population isolates of the Shetland and Orkney Isles in northern Scotland. Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files and Variant Call Format (VCF) files used in this study have been generated in previous studies in Viking Genes14 and by the New York Genome Center (for the 1000 Genomes datasets)20. SV: Structural Variant, VEP: Variant Effect Predictor, CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium.

Variant and star allele calling

Our analysis was largely focused on 33 genes categorised by ClinPGx (formerly PharmGKB) as VIPs (including ACE, ABCB1, ABCG2, ADRB1, ADRB2, CACNA1S, CFTR, COMT, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP4F2, DRD2, DPYD, G6PD, GSTM1, GSTP1, IFNL3, MTHFR, NAT2, NUDT15, RYR1, SLCO1B1, SLC19A1, TPMT, TYMS, UGT1A1 and VKORC1). Secondary to these genes, we analysed 6 drug metabolism and transporter genes (i.e. CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2E1, GSTT1, SLC22A1 and SULT1A1) that are included in the ClinPGx’s former Tier 2 VIP list24. We also included POR owing to its importance in the functioning of CYP genes25, and NAT1 given its proximity to NAT2 and involvement in the metabolism of cotinine. Thus, in total we analysed 41 pharmacogenes. For genes without a standardised star allele nomenclature (ABCB1, ABCG2, ACE, ADRB1, ADRB2, CACNA1S, CFTR, COMT, CYP1A1, CYP2E1, DPYD, DRD2, G6PD, GSTP1, IFNL3, MTHFR, RYR1, SLC19A1, SLC22A1, SULT1A1, TYMS and VKORC1), we subset existing WGS variant call format (VCF) files generated from previous joint-calling analyses on Viking Genes datasets performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit14,26. VCF files for the 1000G European participants were obtained from ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk. For this gene-set, we proceeded directly to the variant annotation steps for the passed SNVs (see below). For genes with a star allele nomenclature (CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP4F2, GSTM1, GSTT1, NAT1, NAT2, NUDT15, POR, SLCO1B1, TPMT, UGT1A1), we used StellarPGx v1.2.8 to determine the corresponding diplotypes for each individual27. StellarPGx (https://github.com/SBIMB/StellarPGx) takes high coverage (≥20x) WGS Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files as input. The pipeline detects single nucleotide variations and indels (herein collectively referred to as SNVs) using GraphTyper, a pangenome-based variant caller28. Following variant detection, StellarPGx retains only variants with quality by depth (QD) >10, and allele balance for heterozygous calls (ABHet) between 0.25 and 0.75 (inclusive), to improve accuracy in the subsequent star allele assignment steps. StellarPGx assigns candidate star alleles, based on core (allele-defining) variant combinations in the VCFs, and then combines this information with copy number changes (if detected) based on read-depth output from SAMtools29 to produce final pharmacogene diplotype calls. Core variants across VIPs typically include missense variants, frameshift variants, stop gain/loss variants, regulatory variants and/or variants resulting in splice defects (https://www.pharmvar.org/criteria). StellarPGx is optimised to detect and phase duplications, and other structural variants, based on read-depth distributions and variant allele depth ratios.

The star allele definitions in the StellarPGx database are based on definitions provided by the Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium database (https://www.pharmvar.org; last accessed March 18, 2025), the UGT nomenclature database (https://www.pharmacogenomics.pha.ulaval.ca/ugt-alleles-nomenclature/), and the TPMT nomenclature committee (https://liu.se/en/research/tpmt-nomenclature-committee). For individuals with novel star alleles, StellarPGx includes a flag in the output indicating the presence of a potential novel allele (this would mean that none of the diplotypes in the StellarPGx database is a match) and recommends extra manual variant inspection and experimental validation. Novel star alleles could be due to occurrence of novel function-altering variants on common haplotypes (‘backbones’) or novel combinations of existing core variants defining other haplotypes in the pharmacogene of interest. In this study, ambiguous diplotype calls that were not due to occurrence of potentially novel star alleles or structural variants were resolved using phasing information from SHAPEIT430.

Variant annotation and phenotype predictions

All the core variants across the VIPs in this study were annotated using the Ensembl variant effect predictor (VEP)31. VEP plugins including SIFT32, Polyphen-233, CADD34, LRT34, PROVEAN35, MutationAssessor36, and AlphaMissense37 were used to predict potential variant deleteriousness. Phenotype predictions for selected VIPs were obtained from diplotype information via published criteria by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Consortium (CPIC; https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines), where applicable.

Statistical analysis

The Fisher’s exact test was used to determine any significant differences in star allele frequencies between different populations. For correction of multiple-testing correction, we applied the false discovery rate p-value adjustment for dependent observations38. In these analyses, p-values < 0.05 indicated a significant difference. Possible deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were investigated using the Genetics package (v1.3.8.1.3) in R v4.1.0 (www.r-project.org/).

Results

The average read depth across the 41 pharmacogenes analysed in the study was 35x and 20x across Shetland and Orkney WGS datasets, respectively (Figure S1). As expected, the X-linked G6PD, and commonly deleted GSTM1 and GSTT1 were outliers in this regard. Across the 41 pharmacogenes, there were 30,539 variants combined across the two datasets. About two-thirds (n=20,334) of these variants were rare (MAF<1%) in both the Shetland and Orkney datasets, with 39% (n=11,922) being singletons in either population. Over 6.7% (n=2038) of the total variants were novel (i.e. not in the database of single nucleotide polymorphisms; dbSNP v154).

Variation in Very Important Pharmacogenes highlighted by CPIC guidelines

Across the Shetland and Orkney datasets, all the participants (100%) had at least one clinically actionable variant and/or star allele combination (diplotype), across 18 of the VIPs with existing Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines. The number of these genotypes per individual varied between 2 and 10 (median=6; mean=5.8) in the Shetland population, while it varied between 2 and 11 (median=6; mean=5.6) in the Orcadian dataset. We observed a comparable distribution in the 1000G European dataset (median=6; mean=5.9; range of 2 to 11 clinically actionable diplotypes). Across gene-drug pairs with CPIC guidelines, the proportion of Shetlanders and Orcadians predicted (based on diplotypes alone) to potentially benefit from pharmacogenetics-guided treatment interventions ranged from 0 to 50.5% (mean = 22.2%), depending on the gene-drug pair. The actionable phenotypes occurred predominantly in CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, IFNL3, SLCO1B1, and VKORC1 (Figure 2 and Table S1). Overall, there were no significant differences in the predicted phenotype distributions between the Shetland, Orkney, and the 1000G European study populations (Table S1).

Predicted pharmacogene phenotype variability (left) across Orcadian and Shetlander study populations in Viking Genes and the proportion of participants that may benefit from genomics-informed drug therapy (right). The phenotypes were predicted from variants and/or star alleles called in the study based on published guidelines by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Consortium (CPIC; https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines). The projected PGx-guided drug dosing recommendations were also based on CPIC guidelines. For example, for ABCG2, a combined 0.8% of the study participants in Orkney and Shetland were predicted to have poor ABCG2 function, while 15.4% were predicted to have decreased ABCG2 function. The CPIC guideline for ABCG2 and rosuvastatin recommends a reduced starting dose of ≤20 mg (and adjustment based on disease-specific and population-specific guidelines) for the individuals with poor ABCG2 function, but not for the individuals with decreased ABCG2 function. Therefore, while the left half of the figure is intended to highlight the variability in the predicted phenotype proportions in Shetland and Orkney, the right half of the figure is meant to summarise what proportions of individuals (per gene-drug pair) are projected to potentially require change in drug/dose if pharmacogenetic testing and CPIC guidelines were to be leveraged.

In CYP2B6, we identified 15 star alleles in the Shetland and Orkney datasets. CYP2B6*6 (decreased function) was the most common clinically actionable allele at a frequency of 17.3% and 16%, respectively. There were no significant differences in the *6 frequency when compared with other European populations (Table 1). Other CYP2B6 decreased function alleles with AF>1% were *7 and *9. CYP2B6*4 and *22 (increased function alleles) were relatively rare (Table 1). CYP2B6*36 (decreased function) was observed in the Shetland dataset (AF=0.4%), but it was absent in the Orkney dataset.

In CYP2C19, we observed 8 star alleles across the Shetland and Orkney datasets. CYP2C19*2 (no function) and *17 (increased) were the most frequently observed clinically actionable CYP2C19 alleles and their frequencies were similar to the distribution in other European populations (Table 1).

In CYP2C9, we observed 7 star alleles across the Shetland and Orkney datasets. The frequency of CYP2C9*2 (decreased function) was slightly higher in the Shetland population (AF=12%) than in Orkney (~8%). Conversely, the frequency of CYP2C9*3 was slightly lower in Shetland (AF=5.6%) than in the Orkney population (AF=7.4%). However, these differences were not statistically significant and the distributions in Shetland were similar to observations among other European populations (Table 1). CYP2C9*11 and *12 were present in both datasets but observably rare (Table S2). Among other genes important for warfarin response, we estimated about 60% of Shetlander and Orcadian participants to have the VKORC1 warfarin low dose phenotype, with 13–14% being homozygous for the clinically actionable rs9923231-T variant (–1639G>A). The frequency of rs9923231-T was similar in both populations (36–37%) and to the frequency in other European populations (Table S3). In CYP4F2, the frequencies of the *3 and *4 alleles (both of which contain the ClinPGx level 1 A rs2108622 variant) were estimated to range between 11–15.5.5% across the Shetland and Orkney populations.

In CYP2D6, we called 37 individual star alleles across the Shetland and Orkney datasets. The allele frequency of CYP2D6*2 (normal function) was estimated to be in the range of 13% to 15%. The frequency of the non-functional CYP2D6*4 allele (defined by rs3892097; splice defect) was observed to be around 17.5% and 16% in Shetland and Orkney (slightly higher than AF in the 1000G European participants i.e. 11.3%), respectively, while the frequency of the CYP2D6*68+*4 hybrid tandem arrangement was estimated to be 2.5–3.5% (lower than in 1000G European participants i.e. around 6%). The ClinPGx resource reported a CYP2D6*4 frequency of 18.5% for the European biogeographical group, but did not have a recorded frequency for *68+*4 at the time of this study. CYP2D6*5 (full gene deletion), *9 (decreased function), and *41 (decreased function) were observed at frequencies of 3.5–5%. Despite observably lower allele frequencies for both *5 and *9, and higher frequencies for *41, in other European populations (Table 1), these differences were not statistically significant. Duplication alleles including CYP2D6*1x2, *2x2, *3x2, and *35x2 were found to be relatively rare (AF≤0.5%) in the Shetland and Orkney populations (Table 1).

In CYP3A5, the *3 allele (splice defect) was observed at frequencies >90% in both Shetland and Orkney. Around 15% of the participants were predicted to be CYP3A5 expressors, but the proportion was significantly higher in the Orkney participants (17.9%) than among the Shetland participants (7%) (p<0.01). In comparison, the proportion of CYP3A5 expressors predicted among the 1000G European participants was 9.4%, and the proportion estimated in ClinPGx among European participants is about 14.2%.

Approximately 6.5% of the Shetland and Orkney participants were predicted to be DPYD intermediate metabolisers. The most common clinically actionable DPYD variations observed in these cohorts were the ‘HapB3’ haplotype variants i.e. rs56038477 (E412E); rs75017182 (splice defect) (frequency of 2.7% and 2.9%, in Shetland and Orkney, respectively). Other known high impact variants observed were rs67376798 (D949V) and rs3918290 (splice defect).

For genes relevant to thiopurine response, we estimated about 8.6% of Shetland and Orkney participants to be TPMT intermediate metabolisers while only 0.4% of participants were NUDT15 intermediate metabolisers (Table S1). The most prevalent alleles contributing to these phenotypes were TPMT*3A (AF of 3.8% and 3.2% in Shetland and Orkney, respectively) and NUDT15*3 (AF of 0.4% and 0.1% in Shetland and Orkney, respectively). The frequency of TPMT*3A in the 1000G European participants (1.6%) was significantly lower than that in Shetland (p=0.002) and Orkney (p=0.005); however, the *3A frequency in other European populations (ClinPGx) was similar to that in Shetland and Orkney. There was no data for *3E in ClinPGx. The frequencies for all TPMT and NUDT15 star alleles in the datasets are provided in Table 2.

Across drug transporter genes with existing CPIC guidelines (SLCO1B1 and ABCG2), we estimated about 21.4% of the Shetland and Orkney participants to have SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1 encoding-gene) decreased function and about 4.7% of the participants to have OATP1B1 increased function. The common SLCO1B1 alleles contributing to the decreased function phenotype included *15 (no function) followed by *2 (no function) (Table 1). SLCO1B1*14 and *20 were the predominant increased function star alleles. The SLCO1B1*20 frequency was relatively elevated in the Shetland population (7.5%) compared to the 1000G European populations (4.8%; p=0.536) and to the data from studies curated by ClinPGx (3.7%; p<0.01) (Table 1). In ABCG2, the frequency of rs2231142 (Q141K) was estimated to be 10.2% and 7.9% in Shetland and Orkney, respectively (Table S3). We predicted 15.4% of the Shetland and Orkney participants to have decreased ABCG2 function, while 0.8% were predicted to have poor ABCG2 function.

In UGT1A1, we predicted 43% of the Shetland and Orkney participants to be intermediate metabolisers and 9.6% to be poor metabolisers. The key UGT1A1*28 allele was found in combination with *80 (i.e. as UGT1A1*28+*80) in nearly every occurrence (Table 2). The second most prevalent non-reference UGT1A1 allele was *66 (AF=11.3% and 12.6% in Shetland and Orkney, respectively).

Across other genes with existing CPIC guidelines (Table S3); for CFTR, rs199826652 (F508del-CFTR) was the more common (average AF=1.7%) of the actionable variants, while rs75527207 (G551D) was rare (AF=0.05%). For IFNL3, around 50% of the participants were predicted to have unfavourable response with regard to Pegylated interferon-α and ribavarin therapy. The average frequency of the IFNL3 rs12979860-T allele was estimated at around 30.2%. In RYR1, only two participants from Shetland had a known clinically actionable variant (rs892052), while no known actionable variants were observed in CACNA1S. In G6PD, only a small subset of Shetlander (2%) and Orcadian (1%) participants, had non-synonymous variant(s). All the non-synonymous G6PD variants were rare, except rs370017540-T (G346D) which, although rare in Orkney (AF<0.1%), was relatively more frequent in Shetland (AF=0.8%).

Variation in VIPs with recently updated star allele nomenclature

In CYP2A6, we called 15 star alleles in Shetland and Orkney combined. Besides CYP2A6*1, CYP2A6*46 (3’-UTR conversion) was the most common allele at a frequency of 27% in Shetland and 34% in Orkney (Table 1). Other CYP2A6 structural variants, including *1x2, *4 (gene deletion), *12 (exons 1–2 from CYP2A7), and *47 (exons 1–8 from CYP2A7) were observably rare (Table S2). Among the star alleles associated with decreased CYP2A6 activity or mRNA expression, CYP2A6*2, *9 and *35 were relatively common but occurred at frequencies <10%.

In NAT2, *1 and *4 (rs1208, R268K) were the only rapid acetylation alleles observed across Shetland and Orkney participants. Among the NAT2 slow acetylation alleles, *5 (rs1801280, I114T), *6 (rs1799930, R197Q; rs1208, R268K), and *16 (rs1801280, I114T; rs1208, R268K) were the most common (Table 2).

Predicted high impact SNVs among variants lacking validated clinical functional annotation

Across VIPs with existing CPIC guidelines, we predicted 176 variants to have potentially high (deleterious) impact on the respective protein, based on the consensus of VEP plugins used in the study (Table S3). Frameshifts, stop gain variants, and splice defects were considered deleterious by default. Among the variants without current CPIC functional annotation, 12 including ACE rs3730025-G (Y244C); CACNA1S rs12139527-G (L1800S), rs3850625-A (R1539C) and rs12406479-C (A69G); CFTR rs1800076-A (R75Q), rs1800098-C (G576A) and rs1800100-T (R668C); CYP2B6 rs35979566-A (I391N); CYP3A4 rs4986910-G (M445T); MTHFR rs1801133-A (A222V) and rs142617551-A (E470V); and NUDT15 rs149436418-G (F52L) were common (AF≥1%) across Shetland and/or Orkney, while the majority were relatively rare (Table S3).

Across pharmacogenes without current CPIC guidelines, 74 variants were predicted to be deleterious by the consensus of VEPs used (frameshifts, stop gain variants, and splice defects were considered deleterious by default). Of these, 11 variants including ABCB1 rs2032582-T (S893T), CYP2A6 rs1801272-T (*2-defining variant; L160H), CYP2E1 rs6413419-A (V179I), DRD2 rs1801028-C (S311C), rs71653614-C (K327E), GSTM1 (N85S), SLC22A1 rs12208357-T (R61C), rs34059508-A (G465R), rs2282143-T (P341L), rs34130495-A (G401S), and SULT1A1 rs376524943-G (G259A) were common (AF≥1%) in Shetland and/or Orkney, while others were relatively rare (Table S3).

Potentially novel star alleles in Shetland and Orkney inferred from WGS data

Across the genes in the current PharmVar database (v6.2.2), we observed a combined total of 46 potentially novel star alleles in CYP2D6, CYP2B6, CYP2A6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and CYP4F2 (Table S4). The most common of these haplotypes included: *9+rs145308399~5576G>A(E97K) in CYP2A6 and *1+rs138264188~17731C>T (T67M) in CYP2B6, especially among Orcadians (AF=0.4% and 0.7%, respectively). We also identified 8 potentially novel suballeles comprising nonsynonymous variants on non-functional backbones in CYP2D6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A5 (Table S4). The more common of these suballeles was *2+rs58973490~17827G>A(R150H) in CYP2C19 (AF=0.2% in Orkney; but observed as a singleton among Shetlander participants). Among the VIPs not yet incorporated into the PharmVar database, we observed a combined total of 7 potentially novel star alleles in GSTM1 and GSTT1. The most common of these haplotypes included: *A+rs147668562~6329A>G(N85S) in GSTM1, especially among Orcadians (AF=1.6%) (Table S4).

Only 13.2% (7 of 53) of the potential novel star alleles occurred in both Shetland and Orkney populations, 45.3% (24 of 53) occurred only in Shetlanders, and 41.5% (22 of 53) occurred only in Orcadians (Table S4). Most of these potentially novel alleles were absent from 1000G European populations, except *9+rs145308399~5576G>A(E97K) in CYP2A6 and *2+rs150216909~7969C>T(R329C) in CYP2D6, both of which were singletons in the 1000G European dataset. Comparatively, CYP2A6*9+rs145308399~5576G>A(E97K), as aforementioned, was relatively more frequent in Orkney. Selected potentially novel star alleles defined by variants predicted to be deleterious are depicted in Figure 3 (functionality predictions by VEP plugins are provided in Table S3).

Discussion

Geographically isolated populations tend to have unique genetic variation patterns characterised by founder variants or enrichment of otherwise rare variants. Several enriched rare deleterious and/or medically relevant variants have been observed in Shetland and Orkney as part of the Viking Genes project, owing to various forms of genetic drift14,15,16. Given that VIPs such as cytochrome P450 genes, among others, tend to harbour a plethora of genetic variants, this study assessed the PGx landscape in Shetland and Orkney in comparison with PGx variation across European populations represented in the 1000 Genomes Project, and data aggregated from literature curated by ClinPGx.

Overall, the distributions of the known pharmacogene variants and star alleles do not vary significantly across Shetland and Orkney. The frequencies of most clinically actionable alleles are comparable to frequencies observed in European cohorts included in this study, and those analysed in other studies39,40. Across genes with a star allele nomenclature, we highlight the occurrence of 53 potentially novel star alleles in Shetland and Orkney combined, majority of which are absent from the 1000G European dataset, and they haven’t been reported in studies curated by ClinPGx. Furthermore, majority of the potentially novel star alleles identified in the Shetland dataset were absent from Orkney and vice versa, thus exemplifying the value of population-specific PGx analysis. In some cases, it is possible to infer the age of the novel star allele from the inheritance pattern across deep pedigrees, e.g. three of the four carriers of CYP2D6 rs199722016-9212A>G (Y490C) trace back to a common ancestor born in 1670, whereas both carriers of CYP2C19 rs144036596-85273G>A (D360N) descend from a couple born in the 1770 s, also in Shetland. The CYP2B6 rs138264188-17731C>T (T67M) variant is observed 18 times in our Orkney dataset and traces to multiple ancestors ~250 years ago, having originated before the 1760s. We predict that larger surveys will pick up more copies of these founder variants.

Predictions based on standardised diplotype-phenotype translation recommendations and CPIC guidelines (https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines) for key gene-drug pairs such as CYP2B6 (efavirenz and sertraline), CYP2C19 (clopidogrel and antidepressants), CYP2C9 (warfarin and NSAIDs), CYP2D6 (opioids, antidepressants, and tamoxifen), IFNL3 (PEGIFN-α & RBV therapy), SLCO1B1 (statins), and VKORC1 (warfarin) showed that up to about 50% of the study participants in both Orkney and Shetland have phenotypes that might warrant treatment adjustments informed by (pre-emptive) pharmacogenetic testing. Moreover, every participant included in the study carried at least one clinically actionable PGx variant. Although our phenotype predictions were not compared with clinical drug response data from the participants, our findings suggest the need for evaluating the benefit of clinical PGx implementation to Shetlanders and Orcadians, especially considering the evidence of ADR reduction (30%) from other European initiatives such as the Pre-emptive Pharmacogenomic Testing for Preventing Adverse Drug Reactions (PREPARE) study7. Optimising drug therapy based on PGx (especially pre-emptively) alongside other precision medicine facets has the potential to mitigate ADRs and enhance treatment efficacy, which may translate into reduced cost of treatment and reducing strain on health systems in the Isles.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, as described in the Methods, there was a discrepancy in the sequencing coverage for the Shetland WGS (30x) and the Orkney WGS (20x) datasets (and indeed for the sample size), which could have affected frequency estimates and novel allele discovery. However, there were very few ambiguous star allele calls (usually expected with low-coverage data) in the lower-coverage Orkney dataset. In addition, the largely similar variant or star allele distributions between the Orcadian and Shetland datasets, the 1000G European datasets, and the ClinPGx reported frequencies justify the use of StellarPGx on the WGS datasets. Secondly, the potential novel alleles identified in the study require further laboratory validation, which was out of the scope of the study. These novel alleles, especially singletons, should therefore be interpreted with caution. We note that in many cases novel alleles were observed to segregate in pedigrees, corroborating their genotype calls. Thirdly, although we presented PGx phenotype predictions based on the diplotypes called in the analysis, several factors (such as age, environment, drug-drug interactions, lifestyle, and microbiome, among others) which are known to impact drug response were not considered in this study. Furthermore, it is difficult to make direct associations regarding the predicted deleterious variants identified in the VIPs in this study with drug response phenotypes.

Conclusion

Herein, we have described the PGx variation across a subset of Shetlander and Orcadian participants that are part of the Viking Genes study. While the PGx landscape and distribution of actionable phenotypes is largely similar to observations across other European populations, the occurrence of potential novel and/or functionally relevant PGx variants or haplotypes enriched within families in these population isolates may warrant tailoring of PGx testing panels. Overall, understanding the distributions of PGx variants, star alleles and phenotypes across Shetland, Orkney, and potentially the broad scope of the Scottish Isles, is informative for research on utility and cost-effectiveness of clinical PGx testing for improved safety and efficacy of drug therapy.

Future directions

Given the relatively high number of potential novel star alleles identified in the Shetland and Orkney datasets included in this study, further (experimental) characterisation of these haplotypes is warranted to support their inclusion in the PharmVar database (https://www.pharmvar.org). We also plan to examine the utility of Viking Genes whole exome sequence data for characterisation of PGx variation across the VIPs included in this study as exome data may be more feasible to generate for purposes of clinical PGx implementation.

Another critical aspect following this analysis is developing practical frameworks for clinical PGx implementation across the Scottish Isles and for communicating PGx test results to various healthcare stakeholders for the optimisation of patient care. This follows similar efforts emerging as part of the Viking Genes study17.

Data availability

The whole genome sequence for Orkney and Shetland are available from the European Genome-Phenome Archive, under accessions EGAD00001005194 and EGAD00001005378, respectively. Other research data and/or DNA samples from the VIKING I and ORCADES studies are available from viking@ed.ac.uk, following approval by the Viking Genes Data Access Committee and in line with the consent given by participants. There is neither Research Ethics Committee approval, nor consent from individual participants, to permit open release of the individual level research data underlying this study. The datasets analysed during the current study are therefore not publicly available. Instead, each approved project is subject to a data or materials transfer agreement (D/MTA) or commercial contract. The 1000 Genomes European datasets were downloaded from http://ftp.sra.ebi.ac.uk. Star allele frequencies for the broader European biogeographical group were obtained from ClinPGx (https://www.clinpgx.org/page/pgxGeneRef).

Code availability

The description of how to run the StellarPGx pipeline can be found at https://github.com/SBIMB/StellarPGx.

References

Van Driest, S. L. et al. Clinically actionable genotypes among 10,000 patients with preemptive pharmacogenomic testing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 95, 423–431 (2014).

Pirmohamed, M. et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 2294–2303 (2013).

Henricks, L. M. et al. DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: A prospective safety analysis. Lancet. Oncol. 19, 1459–1467 (2018).

Coenen, M. J. H. et al. Identification of patients with variants in TPMT and dose reduction reduces hematologic events during thiopurine treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 149, 907-917.e7 (2015).

McInnes, G., Yee, S. W., Pershad, Y. & Altman, R. B. Genomewide association studies in pharmacogenomics. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 637–648 (2021).

Clinical Guideline Annotations. PharmGKB https://www.pharmgkb.org/guidelineAnnotations (2024).

Swen, J. J., Manson, L. E. N., Böhringer, S., Pirmohamed, M. & Guchelaar, H.-J. The PREPARE study: Benefits of pharmacogenetic testing are unclear – Authors’ reply. Lancet 401, 1851–1852 (2023).

Gordon, A. S. et al. PGRNseq: A targeted capture sequencing panel for pharmacogenetic research and implementation. Pharmacogn. Genom. 26, 161 (2016).

Cavallari, L. H. et al. The IGNITE pharmacogenetics working group: an opportunity for building evidence with pharmacogenetic implementation in a real-world setting. Clin. Transl. Sci. 10, 143–146 (2017).

Zhou, Y., Ingelman-Sundberg, M. & Lauschke, V. Worldwide distribution of cytochrome P450 alleles: A meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102, 688–700 (2017).

Sherman, C. A., Claw, K. G. & Lee, S. Pharmacogenetic analysis of structural variation in the 1000 genomes project using whole genome sequences. Sci. Rep. 14, 22774 (2024).

Whirl-Carrillo, M. et al. An evidence-based framework for evaluating pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 563–572 (2021).

Gilbert, E. et al. The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 116, 19064–19070 (2019).

Halachev, M. et al. Regionally enriched rare deleterious exonic variants in the UK and Ireland. Nat. Commun. 15, 8454 (2024).

Kerr, S. M. et al. Clinical case study meets population cohort: Identification of a BRCA1 pathogenic founder variant in Orcadians. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 31, 588–595 (2023).

Kerr, S. M. et al. Two founder variants account for over 90% of pathogenic BRCA alleles in the Orkney and Shetland Isles in Scotland. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 1624–1631 (2024).

Kerr, S. M. et al. An actionable KCNH2 Long QT Syndrome variant detected by sequence and haplotype analysis in a population research cohort. Sci. Rep. 9, 10964 (2019).

Gaedigk, A., Casey, S. T., Whirl-Carrillo, M., Miller, N. A. & Klein, T. E. Pharmacogene variation consortium: A global resource and repository for pharmacogene variation. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 542–545 (2021).

Zanger, U. M. & Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 138, 103–141 (2013).

Byrska-Bishop, M. et al. High coverage whole genome sequencing of the expanded 1000 Genomes Project cohort including 602 trios. bioRxiv 2021.02.06.430068 https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.06.430068 (2021).

McQuillan, R. et al. Runs of homozygosity in European populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet 83, 359–372 (2008).

Halachev, M. et al. Increased ultra-rare variant load in an isolated Scottish population impacts exonic and regulatory regions. PLOS Genetic. 15, e1008480 (2019).

Gilly, A. et al. Gene-based whole genome sequencing meta-analysis of 250 circulating proteins in three isolated European populations. Mol. Metab. 61, 101509 (2022).

VIPs: Very Important Pharmacogenes. PharmGKB https://www.pharmgkb.org/vips (2024).

Miller, W. L. et al. Consequences of POR mutations and polymorphisms. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 336, 174–179 (2011).

Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 43, 11.10.1-11.10.33 (2013).

Twesigomwe, D. et al. StellarPGx: A nextflow pipeline for calling star alleles in cytochrome P450 genes. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 110, 741–749 (2021).

Eggertsson, H. P. et al. Graphtyper enables population-scale genotyping using pangenome graphs. Nat. Genet. 49, 1654–1660 (2017).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Delaneau, O., Zagury, J.-F., Robinson, M. R., Marchini, J. L. & Dermitzakis, E. T. Accurate, scalable and integrative haplotype estimation. Nat. Commun. 10, 5436 (2019).

McLaren, W. et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Gen. Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Kumar, P., Henikoff, S. & Ng, P. C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1073–1081 (2009).

Adzhubei, I., Jordan, D. M. & Sunyaev, S. R. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2 Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. Chapter 7 Unit7.20 (2013).

Rentzsch, P., Witten, D., Cooper, G. M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucl. Acid. Res. 47, D886–D894 (2019).

Choi, Y. & Chan, A. P. PROVEAN web server: A tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatic 31, 2745–2747 (2015).

Reva, B., Antipin, Y. & Sander, C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: Application to cancer genomics. Nucl. Acid. Res. 39, e118 (2011).

Cheng, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 381, eadg7492 (2023).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Annal. Stat. 29, 1165–1188 (2001).

McInnes, G. et al. Pharmacogenetics at Scale: An analysis of the UK Biobank. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 1528–1537 (2021).

Zhou, Y. & Lauschke, V. M. The genetic landscape of major drug metabolizing cytochrome P450 genes—an updated analysis of population-scale sequencing data. Pharmacogn. J. 22, 284–293 (2022).

Acknowledgements

DNA extractions were performed at the Edinburgh Clinical Research Facility, University of Edinburgh. We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the research nurses in Orkney and Shetland, the administrative team in Edinburgh and the people of Orkney and Shetland. We thank Mihail Halachev and John Ireland at the Institute of Genetics and Cancer, University of Edinburgh, UK, for their bioinformatics support and guidance during the research.

Funding

Sydney Brenner Charitable Trust,Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates,SGP/1, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government, CZB/4/276 and CZB/4/710, The Medical Research Council Whole Genome Sequencing for Health and Wealth Initiative, MC/PC/15080, The MRC Human Genetics Unit quinquennial programme “QTL in Health and Disease”, U. MC_UU_00007/10, Arthritis Research UK and the European Union framework program 6 EUROSPAN project, LSHG-CT-2006-018947

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T. and J.F.W. designed and conceptualised the study. D.T. and J.F.W. analysed and interpreted the data. D.T. and J.F.W. drafted the manuscript. T.J.A. and J.F.W. obtained funding and administrative, technical, or material support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Grant support

The Orkney Complex Disease Study (ORCADES) was supported by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government (CZB/4/276, CZB/4/710), a Royal Society URF to J.F.W., the MRC Human Genetics Unit quinquennial programme “QTL in Health and Disease”, Arthritis Research UK and the European Union framework program 6 EUROSPAN project (contract no. LSHG-CT-2006-018947). The Viking Health Study – Shetland (VIKING I) was supported by the MRC Human Genetics Unit quinquennial programme grant “QTL in Health and Disease”. We acknowledge the MRC Human Genetics Unit programme grant, “Quantitative traits in health and disease” (U. MC_UU_00007/10). The Scottish Genomes Partnership was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates (SGP/1) and The Medical Research Council Whole Genome Sequencing for Health and Wealth Initiative (MC/PC/15080). DT is supported by funding from the Sydney Brenner Charitable Trust.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Twesigomwe, D., Aitman, T.J. & Wilson, J.F. Characterisation of pharmacogenomic variation in the Shetland and Orkney Isles in Scotland. Sci Rep 15, 42240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26258-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26258-9