Abstract

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics is a powerful analytical technique for identifying and quantifying proteins in the human plasma, which may be related to the onset, course or the prognosis of schizophrenia. Our study enrolled 46 patients with schizophrenia and 43 healthy controls, who were collected morning fasting venous blood and completed scale assessment. Then mass spectrometry analysis was performed to identify differential proteins and correlation analysis and multiple regression were conducted to explore the relationship between protein biomarkers and psychiatric symptoms, cognitive function and social function in patients with schizophrenia. Compared with the control group, the patient group showed lower immediate and delayed accuracy rates in pattern recognition memory. Alpha-actinin-1 and profilin-1 were positively associated with immediate pattern recognition accuracy. Both were also negatively associated with total number of errors of spatial working memory. Meanwhile, filamin-A was positively associated with immediate accuracy rate and delay accuracy rate of pattern recognition memory. In addition, integrin alpha-M was negatively correlated with factor I of the scale of social function and glutathione synthetase was positively correlated with the total score, factor I, factor II and factor III of the scale of social function in psychosis inpatients. Our study indicated that alpha-actinin-1, profilin-1 and filamin-A may be related to cognitive functions, integrin alpha-M and glutathione synthase may be related to social function outcome of patients with schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is one of the clinically common serious mental disorders, affecting nearly 1% of the world’s population1, and ranked among the top 15 leading causes of disability in the world in 20162, bringing a huge burden of disease3,4. The disease concept of “schizophrenia” was developed from “early-onset dementia” proposed by Kraepelin more than 100 years ago5. The clinical manifestations mainly include positive psychiatric symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions and speech disorders, negative symptoms such as decreased motivation and decreased expression ability, and cognitive function defects involving executive function and memory6. The disease usually starts in young adults, illnesses out, seriously affect the social function and quality of life of patients.

It is well known that cognitive impairment is one of the core symptoms of schizophrenia7. Studies have found that patients with first-episode schizophrenia have impairment of overall neurocognitive function, including processing speed, attention, visual learning, working memory, language learning, problem solving, and social cognition, especially processing speed and attention8. Cognitive dysfunction is closely related to the pathology of psychiatric symptoms9, especially interacting with negative symptoms, and its stable existence often means more serious impairment of social function and worse prognosis10,11. In terms of social functions, patients with schizophrenia have deficiencies in areas such as self-care in daily life, interpersonal relationships, occupational functions, and schooling11, greatly reducing the quality of life of themselves and their caregivers. Tools for assessing social functions include, for example, the Personal and Social Performance Scale12 and the Social Functioning Scale13, etc. So far, however, schizophrenia etiology is still unclear, lacking of objective diagnostic index and clinical biological markers associated with social function outcome. Antipsychotics can significantly reduce the severity of mental symptoms and recurrence risk14, however, drugs are most effective in alleviating positive symptoms, and have very limited effects on negative symptoms, cognitive impairment or social function11. Some patients with schizophrenia may experience poor recovery of cognitive and social functions and increase social and economic burden, thus finding the biomarkers associated with schizophrenia in order to expand more targeted therapy and improve the prognosis of patients is the urgent need to solve clinical problems.

Existing proteomics researches have shown that the pathology of schizophrenia related to inflammation, stress response signals, congenital or acquired immune and energy metabolism process, such as its related proteins is expected to become the disease biomarkers, but nothing has been decided yet15,16,17,18. Peripheral blood is an easily accessible biological sample matrix that can reflect the physiological and pathological conditions of the entire body, therefore, more and more scholars have been trying to find the peripheral blood biomarkers of the disease15,19,20, which will be extremely significance and simple thing for the clinic in the future. Therefore, this study aims to explore potential associations between protein biomarkers and psychiatric, cognitive, and social functioning in schizophrenia.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects of this study were divided into the patient group and the control group, who were selected respectively from inpatients of Suzhou Guangji Hospital and the general healthy population in the community from December 2020 to November 2021. A total of 46 patients with schizophrenia (13 females and 33 males) and 43 healthy volunteers (19 females and 24 males) were enrolled in this study, and the median and quartile age of the patient group was 46.00 (38.75, 52.00), and that of the control group was 38.00 (30.00, 51.00). The clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia was made by two experienced psychiatrists according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) criteria. The patients meet the aged 18–65, enough to understand the research content, in a stable condition, can cooperate to study, adequate understanding of the study content and completion of the informed consent process. The healthy control subjects need to have no history of DSM-5 diagnosis, no family history of mental illness, 18–65 years old, and the cognitive function are able to understand the content of the study while completing the informed consent process. We excluded potential participants who have organic brain disease and other serious body disease, or abnormal blood count, heart, liver, or kidney function recently, a history of other mental illnesses such as intellectual disability, alcohol or drug dependence, mood disorders, performed electroconvulsive therapy, and pregnant or lactating women. All of the subjects were from Han Chinese population in Jiangsu Province. The gender, age between the schizophrenia group and the healthy control group had no obvious statistical difference (Table 1).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Suzhou Guangji Hospital. The ethical approval number is “2020–009” and the ethical approval date is October 22nd, 2020. The start date of the study and participant recruitment date are both December 2020. Written informed consent was voluntarily provided by all subjects or their legal guardians.

Study design

Patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers were enrolled in this case–control study. First, the general demographic data such as name, gender, age, and clinical data such as duration of illness and dosage of antipsychotic drugs were collected by self-made information tables. In patient group, a total of 5 ml of fasting cubital venous blood was collected in ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid anticoagulant tubes and centrifuged by Eppendorf (Eppendorf in Germany) centrifuge at 3000 RPM for 10 min. The separated plasma was placed in aliquots and stored in a − 80 °C refrigerator. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS), scale of social function in psychosis inpatients (SSPI), and the Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery (CANTAB) were also completed. In the control group, blood samples were collected, centrifuged, frozen, and the short form health survey (SF-36) and CANTAB were completed. The blood samples collected from the patients and the control group were solely used for research purposes.

Tools for assessment

In this study, multiple assessment tools were used to assess the clinical symptoms, social function and cognitive function of the subjects. In order to ensure the consistency of assessment, all scales were completed by the same trained researcher. Clinical scale evaluation content includes PANSS21, SSPI22,23, SF-3624 and CANTAB.

The SSPI assessment consists of 12 items, each rated on a scale of 0 to 4. 0 indicates the absence of the function; 1 indicates the need for assistance to perform the function; 2 indicates the presence of the function but requiring supervision to complete it; 3 indicates the ability to perform the function independently but with low initiative and enthusiasm; 4 indicates that the function remains in good condition all the time. It is divided into 3 factors: Factor 1, Daily Living Ability (including items 1 to 3), the higher the score, the better the patient’s self-care ability; Factor 2, Activity and Interpersonal Skills (including items 4 to 8), the higher the score, the stronger the normal activity ability and better the interpersonal situation of the patient; Factor 3, Social Activity Skills (including items 9 to 12), the higher the score, the better the social activity skills of the patient. Social Function Deficiency Grading: < 18 points indicate severe deficiency, 18 to 28 points indicate moderate deficiency, 29 to 38 points indicate mild deficiency.

The CANTAB was developed by the University of Cambridge in the late 1980s based on the neural correlation paradigm in animal experiments and human cognitive neuropsychology25. It mainly presents eight computerized neuropsychological tests on the touch screen, which is not affected by language and culture, simple and reliable26, and has game-like and attractive characteristics27. CANTAB mainly targets specific cognitive domains of visual memory, attention, working memory, and planning and executive functions25. This study mainly selected pattern recognition memory (PRM) and spatial working memory (SWM) modules to test patients’ memory and other cognitive functions.

PRM is designed to reflect short-term visual memory function. In the test, a computer screen presented a series of 12 non-describeable images sequentially at a rate of one per second. After viewing the images, participants were asked to choose between two images, only one of which had been shown before. The module is divided into immediate model and delay model, the former for immediate recognition, the latter for 20 min before delay recognition. The main test indexes were the correct rate of immediate recognition and the correct rate of delayed recognition. SWM measures the ability to retain spatial information, working memory, and use heuristic strategies, and is a sensitive measure of frontal executive function. At test time, a number of colored squares were displayed on the screen, and subjects found the blue “mark” by clicking on each square and placed it in a blank column by touching the right side of the screen. Increases the number of squares from three to eight, color and position for each test, in case of using rigid search strategy. The participant had to touch each square in turn until all the blue marks were found, but the clicked square was covered up again. Touching any square that had been found was a mistake, and the participant should try to avoid clicking repeatedly. The test indexes mainly included the total number of search errors and strategy score. The more errors and the higher strategy score indicated the worse cognitive function.

Determination of proteins

Sample preparation

Lysis solution (8 M Urea/100 mM Tris–Cl) was added to the plasma samples of all subjects. After sonication in a water bath, dithiothreitol was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, iodoacetamide was added and the sulfhydryl group was blocked by alkylation reaction at room temperature in the dark. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford (Sangon-C503031-1000) method. After protein quantification, 50 μg of samples were used for SDS-PAGE, and the protein bands were observed after Coomassie brilliant blue staining. A 100 mM Tris–HCl solution was added to the reduced and alkylated sample, then the concentration of Urea (Sigma-U6504-50G) was diluted to less than 2 M, and trypsin (SignalChem-T575-31N-10 mg) was added according to the mass ratio of enzyme to protein of 1:50. The samples were incubated at 37 °C overnight with shaking and digested. The next day, trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich-299537-100G) was added to terminate digestion, and the supernatant was removed for Sep-Pak C18 desalting, drained and frozen at − 20 °C until use.

Mass spectrometry detection

Mass spectrometry data were collected using an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an EASY-nLC 1200 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) liquid phase LC–MS system. Peptide samples were dissolved in loading buffer, inhaled by an autosampler, and bound to an analytical column (75 mu m * 25 cm, C18, 1.9 mu m, 100 a) for separation. Two mobile phases (mobile phase A: 0.1% formic acid and mobile phase B: 0.1% formic acid, 80% this ACN) were used to establish an analytical gradient. The flow rate of the liquid phase was set to 300nL/min. Mass spectrum acquired data in a data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode, and each cycle of scans contained one MS1 scan (R = 60 K, AGC = 3e6, Max IT = 30 ms, scan range = 350–1250 m/z) and 40 MS2 scans (R = 30 K, AGC = 1000%, Max IT = 50 ms) with variable Windows. Turn on the FAIMS function (CV-45) and set the collision energy to 30.

Protein database search and analysis

DIA raw data files were analyzed by DIA-NN (v1.7.16) software. Firstly, Swissprot (Human, 20210312) database was used to predict a spectrum library by the deep learning algorithm in DIA-NN, and the predicted spectrum library and the spectrum library obtained by the MBR function were used to extract the original DIA data to obtain protein quantitative information. The final results were filtered at the parent ion and protein levels with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. The ratio of repeated quantitative means of each protein in two sets of samples was used as the fold difference (FC) and the FC threshold was set. The relative quantitative values of each protein in the two groups of samples were further tested by t-test to judge the significance of the difference, and the corresponding P value was calculated. The default P value was < 0.05, and the proteins with significant differences between the groups were obtained. The differential proteins were displayed by volcano diagram by R (base package, 3.5.1), and the change trend of differential proteins was evaluated.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 24.0 version of the statistical analysis software. The Komolgorov–Smirnov test was used to test for normal distribution when the sample size was greater than 50, and the Shapiro–Wilk test was used otherwise. The measurement data following normal distribution were expressed as mean plus or minus standard deviation (x ± s), and the independent sample T test was used for comparison between the two groups. Quantitative data with skewed distribution were expressed as median and quartile [M (P25, P75)], and comparison between groups was analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The number and percentage of cases were used to describe the count data, and the chi-square test was used for comparison between groups. The quantitative data of the identified differential proteins were correlated with the scores of PANSS, SSPI, SF-36, PRM and SWM. Pearson correlation analysis was used when two groups of data conform to normal distribution, and the Spearman correlation analysis was used when the data are not accord with normal distribution. Multiple linear regression was used to control for confounding factors. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General demographic data and scale evaluation analysis

A total of 46 patients with schizophrenia and 43 healthy volunteers were enrolled in this study. There was no significant difference in age, gender and body mass index (BMI) between the two groups (P > 0.05). According to statistics, the median and quartile age of the patient group was 46.00 (38.75, 52.00), and that of the control group was 38.00 (30.00, 51.00). Other general data and clinical scale evaluation and analysis are also shown in Table 1.

Differential protein analysis

In this experiment, FC > 1.5 or FC < 0.67 and P value < 0.05 were used as the criteria for up-regulation or down-regulation of differentially expressed proteins. Through analysis, a total of 34 differentially expressed proteins were identified and screened. Compared with the healthy control group, 22 proteins were up-regulated and 12 proteins were down-regulated in the schizophrenia group, as shown in Table 2. At the same time, the difference of each protein multiples to 2 at the bottom of the exponential, P value to 10 for the absolute value of the exponential, map the volcano, as shown in Fig. 1.

Volcano plot of differential proteins. The horizontal axis represents the fold change (log2 value) of the differentially expressed proteins, the vertical axis represents the P value (− log10 value), blue represents the proteins with no significant difference, red represents the up-regulated proteins, and green represents the down-regulated proteins.

The analysis of candidate proteins in schizophrenia and their association with cognitive function

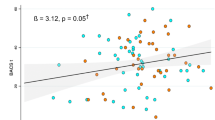

Through the above research results, combined with a large number of literature reading, five proteins including neural cell adhesion molecule L1 (L1), integrin alpha-M, alpha-actinin-1, filamin-A and profilin-1 associated with synapses were selected as schizophrenia candidate proteins for correlation analysis. Due to some objective reasons, finally 40 people in the patient group and 41 people in the control group completed the full cognitive assessment. There was no significant difference in age, gender and BMI between the two groups (P > 0.05), but there was a significant difference in education level (P < 0.05) (see Table 3 and Fig. 2).

Multiple linear regression was used to control for the confounding factor of age, sex and educational background. The results showed that the immediate and delay accuracy rate of PRM in the patient group were lower than those in the control group, which indicated that the cognitive function of the patient group were worse than that of the control group (see Table 4).

Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted after controlling for age, sex, educational background, duration of illness and antipsychotic drug dosage in the schizophrenia group. The results showed that alpha-actinin-1 was positively associated with immediate accuracy rate of PRM and negatively associated with total number of errors of SWM. Profilin-1 was also positively associated with immediate accuracy rate of PRM and negatively associated with total number of errors of SWM. Meanwhile, filamin-A was positively associated with immediate accuracy rate and delay accuracy rate of PRM (see Table 5).

The correlation between differential proteins and mental symptoms and social function

In the patient group, spearman correlation analysis showed that there was no significant correlation between the five candidate proteins and PANSS total score, positive score, negative score, and general pathological score (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 6. While integrin alpha-M in the candidate proteins was negatively correlated with SSPI factor I (r = − 0.292, P = 0.049). And there was no significant correlation between the other four candidate proteins and the total score of SSPI, factorI, factor II and factor III (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 6. In addition, this study found that the differential protein glutathione synthetase was positively correlated with all SSPI scores, as shown in Table 7.

Discussion

This case–control study aimed to find the molecular biomarkers related to the diagnosis and prognosis of schizophrenia by mass spectrometry based proteomics analysis, and to analyze the correlation between biomarkers and psychiatric symptoms, cognitive function, and social function status. Interestingly, 34 differentially expressed proteins were identified between the schizophrenia group and the control group, of which five proteins, namely cell adhesion molecule L1, integrin alpha-M, alpha-actinin-1, filamin-A and profilin-1, were considered as candidate protein markers. In addition, alpha-actinin-1, filamin-A, profilin-1, integrin alpha-M and glutathione synthetase, were found to be associated with cognitive or social function in schizophrenia, extending the current findings and providing new research directions.

Differential protein expression profile in plasma of patients with schizophrenia

A total of 7633 peptides and 668 proteins were identified in patients with schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Through quantitative expression analysis of differential proteins, a total of 34 differential proteins were screened. The identified differential proteins neural cell adhesion molecule L1, integrin alpha-M, alpha-actinin-1, filamin-A and profilin-1 were used as candidate protein markers. It is speculated that they may be involved in the pathological process of the occurrence and development of schizophrenia.

Among them, neural cell adhesion molecule L1, also known as CD171, is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed in the nervous system, which plays a key role in neuronal migration, axon growth and synapse formation28. Its coding gene is L1CAM. The L1 family of cell adhesion proteins include L1, CHL1 (a close homolog of L1), NrCAM, and neurofascin. These molecules regulate neuronal development and neural networks, and their defects have been linked to various neurological diseases29. A Japanese study found that L1CAM gene mutation of some base pairs were positively correlated with male schizophrenia, but has nothing to do with female schizophrenia30. Our study found that L1 expression was upregulated in patients with schizophrenia compared with healthy controls. In other studies, L1CAM immunoreactive protein was reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with schizophrenia compared with normal controls31,32, while the study of brain tissue after death failed to show significant changes of protein in schizophrenia33,34. These results were inconsistent with our result, which may be due to the fact that the samples in our study were derived from peripheral blood, which is different from cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue. Therefore, whether peripheral blood can reflect the protein-related pathological changes of patients with schizophrenia remain to be further verified. At present, some scholars believe that schizophrenia is a synaptic disorder, which is characterized by the functional disruption of synaptic regulatory proteins35. The L1 family can mediate spinal pruning during development and plays an important role in the regeneration of the nervous system, which is associated with synapse formation and plasticity35. It is also involved in the formation of the myelin sheath that surrounds many axons36. In conclusion, the present studies suggest that L1 is involved in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, but more studies are needed to confirm the specific association of L1 in peripheral blood.

Differences in cognitive function between patients with schizophrenia and normal controls

In the analysis of cognitive function, the results of our study showed that the cognitive function of patients with schizophrenia was worse than that of healthy controls in immediate and delay short-term visual memory, which was also consistent with the recognized view of cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia37.

Relationship among alpha-actinin-1, profilin-1, filamin-A and cognitive function in schizophrenia

The multiple linear regression analysis between candidate proteins and cognitive indicators after controlling for age, sex, educational background, duration of illness and antipsychotic drug dosage in schizophrenia group, we found that the higher the alpha-actinin-1 concentration, the higher immediate accuracy rate of PRM and the lower total number of errors of SWM. And profilin-1 was also positively associated with immediate accuracy rate of PRM and negatively associated with total number of errors of SWM. Additionally, filamin-A was positively associated with immediate accuracy rate of PRM and delay accuracy rate of PRM. As we know PRM is designed to reflect short-term visual memory function, and SWM measures the ability to retain spatial information, working memory, and use heuristic strategies, and is a sensitive measure of frontal executive function. Hence, the above results indicate that all the three proteins are associated with better cognitive function.

Alpha-actin, one of the first muscle cell molecules with the function of crosslinking with actin filament bodies38 and later found in non-muscle cells39, is a ubiquitous cytoskeletal protein in eukaryotes. At present, there are four known types of alpha-actin, including 1, 2, 3 and 4, among which 1 and 4 are expressed in non-muscle cells, and may be an important molecule in immune response40. Alpha-actin is a transmembrane protein that can stabilize and maintain cell shape, and play an important role in the connection of cytoskeletal structures to the plasma membrane41. Existing studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia had defects in cortical dendritic spines that involved altered regulation of the actin cytoskeleton required for spine formation and maintenance42,43,44. Studies of autopsy brain tissue have found that actin polymerization in the anterior cingulate cortex was reduced in elderly patients with schizophrenia, and it has been confirmed that the density of dendritic spines and synaptic plasticity were reduced in schizophrenia45. However, the present study found that the expression of alpha-actin-1 is up-regulated in schizophrenia, probably due to the number of actin isoforms, and the autopsy study did not specify the type of actin. Moreover, there may be some differences in the pathological mechanism reflected by brain tissue and blood. Actin isoforms may reflect the pathological process of schizophrenia to a certain extent, and more studies from peripheral blood are needed to confirm this in the future.

Filamin A, also known as actin-binding protein 280 (ABP-280), is an actin binding protein with a molecular weight of 280 kda46 and is also a widely expressed cytoskeleton-related protein. It plays an important role in regulating cell morphology and movement47. Filamin A has been reported to interact with the third cytoplasmic loop of dopamine 2 (D2) and dopamine 3 (D3) receptors, suggesting a molecular mechanism by which cytoskeletal protein interactions regulating D2 and D3 receptor signaling47,48. Filamin A and spinophilin link D2 receptors to the actin cytoskeleton and can serve as scaffolds to assemble the various components of the D2 receptor signaling complex, capable of promoting D2 receptor aggregation49. At the same time, filamin A is also thought to be required for neuronal migration in humans, and filamin A interacting protein and filamin A may be involved in cortical development, representing one of the interlinked protein networks with psychiatric disorders50. Our study found upregulation of filamin A expression compared with controls, and there are relatively few studies on the expression characteristics of filamin A in schizophrenia. Filamin A is also involved in the regulation of cell adhesion and mechanical sensors, helping cells to adapt to changes in their microenvironment51. This function is achieved by regulating the response of the cytoskeleton to external signals, thereby influencing cell movement and positioning52. This adaptability is particularly important for neurons that need to maintain flexibility to adapt to the continuous remodeling of synapses and neural networks, which are the basis of learning and memory53. Interestingly, our study found that Filamin A is possitively related to the short-term spatial memory of schizophrenia. At present, there are few studies on the specific regulatory mechanism of filamin A on the cognitive function of schizophrenia and it is necessary to conduct in-depth research. Therefore, filamin A may also be one of the proteins related to the pathological mechanism and cognitive function of schizophrenia, which is worthy of further study in the future.

Profilin, discovered in the 1970s, was one of the first actin binding proteins identified54, catalyzing actin activity in a concentration-dependent manner: at high concentrations, actin polymerization is prevented, while at low concentrations, it appears to be promoting55. To date, four isoforms of profilin have been identified, of which profilin-1 is of particular interest because of its role in the cytoskeleton, cell signaling, and its link to diseases such as cancer and vascular hypertrophy, and it is present in almost all tissues and cells, including platelets, lymphocytes, glia, and so on54. Profilin-1 also has a role in shaping synaptic structure and is an important regulator of synaptic plasticity, and its deficiency may adversely affect neuronal development54,56. In a mouse model of prenatal stress which is an effective model for schizophrenia and affective disorders, researchers have found that profilin-1 was up-regulated in the mouse hippocampus by proteomic analysis, suggesting that it could interfere with cytoskeleton remodeling during development56. Our study found that profilin-1 was also upregulated compared with controls which was consistent with the results in mice. At present, there are relatively few studies on this protein and schizophrenia, so more human studies are needed in the future to verify the association between them.

At present, there are relatively few studies on the association between these three proteins and the cognitive functions of schizophrenia. Our research found that after excluding factors such as gender, age, years of education, disease duration, and the dosage of antipsychotic drugs, these three proteins still showed a positive correlation with cognitive function. Moreover, our study also discovered that these protein levels in patients with schizophrenia were all upregulated compared to normal controls. It is not yet clear whether these three proteins have a negative feedback regulation or protective effect on the cognitive functions of schizophrenia. Therefore, the regulatory effects or mechanisms of these proteins on the cognitive functions of patients with schizophrenia require more in-depth research. Our research has identified the association between the three proteins and the cognitive aspects of schizophrenia, providing more references and perspectives for future studies.

Relationship between integrin alpha-M and social function in schizophrenia

Our study also found that integrin alpha-M was negatively correlated with factor I of SSPI, which represented daily living ability, suggesting a possible association between integrin alpha-M and social functioning in schizophrenia. However, no studies related to integrin alpha-M and social function in schizophrenia have been searched so far, so the specific association can be further verified by combining longitudinal or follow-up studies in the future. No significant correlation was found between the levels of candidate proteins and psychiatric symptoms of patients with schizophrenia in this study, which may be due to the relatively stable condition of the patient group members in this study after treatment, and the possibility that the relevant results could be affected by antipsychotic drugs.

Relationship between glutathione synthetase and social function in schizophrenia

Our study found that glutathione synthetase was positively correlated with the total SSPI score and the three factor scores in the patient group, suggesting that glutathione synthetase may be able to reflect the social function status of patients to some extent. Previous studies have shown that energy metabolism is altered in schizophrenia, resulting in impaired redox balance57. Glutathione, which is especially important in antioxidant defense, is produced by the sequential reaction of two enzymes, γ-glutamylcysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthase (GSH). The former includes the modification subunit GCLM and the catalytic subunit GCLC58. Reduced glutathione levels were found in blood and postmortem brain tissues of patients with schizophrenia59,60. Some studies have also reported that glutathione metabolic enzymes, including GCLM, GCLC, glutathione peroxidase, and glutathione reductase may be related to schizophrenia, but no relevant reports have been found on glutathione synthetase and schizophrenia61,62. The level of glutathione peroxidase was low in patients with schizophrenia, and its dysregulation could lead to oxidative stress, increase gene and histone methylation, and leaded to epigenetic changes in treatment-resistant schizophrenia63.

Substances that stimulate glutathione synthesis may be a treatment for neurodegenerative diseases and schizophrenia58. The antioxidant N-acetylcysteine, as a precursor of cysteine in GSH synthesis, may be an adjunctive strategy for the treatment of psychiatric disorders64. A study in a rat model of schizophrenia showed that long-term treatment with aripiprazole or N-acetylcysteine reversed social and cognitive deficits and reduced exploratory behaviors65. Early studies found that the antipsychotic drug risperidone could significantly increase the content of glutathione in schizophrenia66, and higher glutathione levels were associated with shorter drug onset time, suggesting a good prognosis67. Our study found that the level of glutathione synthase in patients with schizophrenia after stable drug treatment was up-regulated compared with healthy controls, and was positively correlated with social function. This suggest that glutathione synthase may be beneficial to the social function recovery of patients with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, glutathione levels were not measured in this study. Whether the elevated expression of glutathione synthetase means that glutathione levels are increased cannot be determined. Whether glutathione or glutathione synthetase levels are related to disease recovery is not conclusive, but it provides a direction for future research on biomarkers related to patient prognosis. It is interesting to further study the specific association and regulatory mechanism of glutathione synthetase with cognitive and social function recovery in schizophrenia.

There are some major innovations in this study. Firstly, a case–control quantitative proteomic study was conducted to identify potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of schizophrenia by using mass spectrometry detection and bioinformatic analysis. Secondly, this study selected multi-dimensional scales to assess psychiatric symptoms, cognitive function and social function, in order to explore the biological indicators related to clinical symptoms and prognosis of schizophrenia. This study also has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size of the study was relatively small, which may affect the statistical power. Secondly, all patients in this study were treated with antipsychotic drugs, so the identified differential proteins may be interfered by drugs. Thirdly, although we adopted the method of sampling in the early morning on an empty stomach, the biological rhythms such as the changes between day and night, may have certain effects on the protein expression levels. Therefore, in future studies, it might be necessary to consider factors such as the influence of circadian rhythms on protein expression levels.

Conclusion

This study suggested that pattern recognition memory of patients with schizophrenia were worse than that of healthy controls. The alpha-actinin-1, profilin-1 and filamin-A protein may play an important role in cognitive functions of schizophrenia, meanwhile, integrin alpha-M may be negatively related to social function, while glutathione synthetase may be positively related to social function in schizophrenia.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD069411.

References

Millan, M. J. et al. Altering the course of schizophrenia: Progress and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 485–515 (2016).

Global, R. & Incidence, N. Prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259 (2017).

Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E. & Druss, B. G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 72, 334–341 (2015).

Moreno-Kustner, B., Martin, C. & Pastor, L. Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological Issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 13, e195687 (2018).

McGlashan, T. H. Eugen Bleuler: centennial anniversary of his 1911 publication of dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 1101–1103 (2011).

Marder, S. R. & Cannon, T. D. Schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1753–1761 (2019).

Havelka, D., Prikrylova-Kucerova, H., Prikryl, R. & Ceskova, E. Cognitive impairment and cortisol levels in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Stress. 19, 383–389 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive function in Chinese first-episode schizophrenia: Matrics consensus cognitive battery (Mccb) profile of impairment. Gen. Psychiat. 32, e100043 (2019).

Wu, J. Q. et al. Cognitive impairments in first-episode drug-naive and chronic medicated schizophrenia: Matrics consensus cognitive battery in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatry Res. 238, 196–202 (2016).

Bhat, P. S., Raj, J., Chatterjee, K. & Srivastava, K. Cognitive dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia and its correlation with negative symptoms and insight. Ind. Psychiatry J. 30, 310–315 (2021).

Mueser, K. T., Deavers, F., Penn, D. L. & Cassisi, J. E. Psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 465–497 (2013).

Hoşgelen, E. I., Akdede, B. B. & Alptekin, K. Relationship between the use of mobile applications and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Turk. J. Psychiatry 36, 138 (2024).

Lane, E., Gray, L., Kimhy, D., Jeste, D. & Torous, J. Digital phenotyping of social functioning and employment in people with schizophrenia: Pilot data from an international sample. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 79, 125–130 (2025).

Lieberman, J. A. et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1209–1223 (2005).

Sabherwal, S., English, J. A., Focking, M., Cagney, G. & Cotter, D. R. Blood biomarker discovery in drug-free schizophrenia: The contribution of proteomics and multiplex immunoassays. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 13, 1141–1155 (2016).

Davalieva, K., Maleva, K. I. & Dwork, A. J. Proteomics research in schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 10, 18 (2016).

Guest, P. C. et al. Proteomic profiling in schizophrenia: Enabling stratification for more effective treatment. Genome Med. 5, 25 (2013).

Nascimento, J. M. & Martins-de-Souza, D. The proteome of schizophrenia. Npj Schizophr. 1, 14003 (2015).

Harris, L. W. et al. Comparison of peripheral and central schizophrenia biomarker profiles. PLoS ONE 7, e46368 (2012).

Schwarz, E. et al. Identification of a blood-based biological signature in subjects with psychiatric disorders prior to clinical manifestation. World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 13, 627–632 (2012).

He, & Zhang,. The Chinese norm and factor analysis of PANSS. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 8, 65–69 (2000).

Zhou, C., Jia, S. & Pu, J. A self-designed scale for social function in in-patients with psychosis (SSFPI) and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Sichuan Mental Health 17(3), 144–146 (2004).

Song, et al. Application of social function rating scale for psychiatric inpatients in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Chin. J. Rehabil. 28, 316–3176 (2013).

Li, L. W. H. S. Y., Wang, H. & Shen, Y. Development and psychometric tests of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey Scales. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 36(2), 109–113 (2002).

Fray, P. J. & Robbins, T. W. Cantab battery: Proposed utility in neurotoxicology. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 18, 499–504 (1996).

Barnett, J. H. et al. Assessing cognitive function in clinical trials of schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 1161–1177 (2010).

Levaux, M. N. et al. Computerized assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: Promises and pitfalls of cantab. Eur. Psychiat. 22, 104–115 (2007).

Maness, P. F. & Schachner, M. Neural recognition molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily: Signaling transducers of axon guidance and neuronal migration. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 19–26 (2007).

Wei, C. H. & Ryu, S. E. Homophilic interaction of the L1 family of cell adhesion molecules. Exp. Mol. Med. 44, 413–423 (2012).

Kurumaji, A. An association study between polymorphism of L1Cam gene and schizophrenia in a Japanese sample. Am. J. Med. Genet. 105, 99–104 (2001).

Poltorak, M. et al. Disturbances in cell recognition molecules (N-Cam and L1 Antigen) in the Csf of patients with schizophrenia. Exp. Neurol. 131, 266–272 (1995).

Poltorak, M. et al. Monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia are discordant for N-Cam and L1 in Csf. Brain Res. 751, 152–154 (1997).

Vawter, M. P. et al. Abnormal expression of cell recognition molecules in schizophrenia. Exp. Neurol. 149, 424–432 (1998).

Webster, M. J., Vawter, M. P. & Freed, W. J. Immunohistochemical localization of the cell adhesion molecules Thy-1 and L1 in the human prefrontal cortex patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Mol. Psychiatry. 4, 46–52 (1999).

Duncan, B. W., Murphy, K. E. & Maness, P. F. Molecular mechanisms of L1 and Ncam adhesion molecules in synaptic pruning, plasticity, and stabilization. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 625340 (2021).

Hortsch, M., Nagaraj, K. & Mualla, R. The L1 family of cell adhesion molecules: A sickening number of mutations and protein functions. Adv. Neurobiol. 8, 195–229 (2014).

Fett, A. K. et al. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 573–588 (2011).

Maruyama, K. & Ebashi, S. Alpha-Actinin, a new structural protein from striated muscle. II. Action on actin. J. Biochem. 58, 13–19 (1965).

Mimura, N. & Asano, A. Actin-related gelation of ehrlich tumour cell extracts is reversibly inhibited by low concentrations of Ca2+. Nature 272, 273–276 (1978).

Oikonomou, K. G., Zachou, K. & Dalekos, G. N. Alpha-Actinin: A multidisciplinary protein with important role in B-cell driven autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 10, 389–396 (2011).

McGough, A., Way, M. & DeRosier, D. Determination of the alpha-actinin-binding site on actin filaments by cryoelectron microscopy and image analysis. J. Cell. Biol. 126, 433–443 (1994).

Yan, Z., Kim, E., Datta, D., Lewis, D. A. & Soderling, S. H. Synaptic actin dysregulation, a convergent mechanism of mental disorders?. J. Neurosci. 36, 11411–11417 (2016).

Borovac, J., Bosch, M. & Okamoto, K. Regulation of actin dynamics during structural plasticity of dendritic spines: Signaling messengers and actin-binding proteins. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 91, 122–130 (2018).

Carlisle, H. J. et al. Deletion of densin-180 results in abnormal behaviors associated with mental illness and reduces Mglur5 and Disc1 in the postsynaptic density fraction. J. Neurosci. 31, 16194–16207 (2011).

Bhambhvani, H. P., Mueller, T. M., Simmons, M. S. & Meador-Woodruff, J. H. Actin polymerization is reduced in the anterior cingulate cortex of elderly patients with schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 7, 1278 (2017).

Cho, E. Y. et al. Roles of protein kinase C and actin-binding protein 280 in the regulation of intracellular trafficking of dopamine D3 receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 21, 2242–2254 (2007).

Li, M., Bermak, J. C., Wang, Z. W. & Zhou, Q. Y. Modulation of dopamine D(2) receptor signaling by actin-binding protein (Abp-280). Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 446–452 (2000).

Lin, R., Karpa, K., Kabbani, N., Goldman-Rakic, P. & Levenson, R. Dopamine D2 and D3 receptors are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via interaction with filamin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 5258–5263 (2001).

Koh, P. O., Bergson, C., Undie, A. S., Goldman-Rakic, P. S. & Lidow, M. S. Up-regulation of the D1 dopamine receptor-interacting protein, calcyon, in patients with schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 311–319 (2003).

Yagi, H. et al. Filamin a interacting protein plays a role in proper positioning of callosal projection neurons in the cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 612, 18–24 (2016).

Nakamura, F. The role of mechanotransduction in contact inhibition of locomotion and proliferation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2135 (2024).

Sutherland-Smith, A. J. Filamin structure, function and mechanics: Are altered filamin-mediated force responses associated with human disease?. Biophys. Rev. 3, 15–23 (2011).

Holtmaat, A. & Caroni, P. Functional and structural underpinnings of neuronal assembly formation in learning. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1553–1562 (2016).

Alkam, D., Feldman, E. Z., Singh, A. & Kiaei, M. Profilin1 biology and its mutation, actin (G) in disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74, 967–981 (2017).

Yarmola, E. G. & Bubb, M. R. How depolymerization can promote polymerization: The case of actin and profilin. BioEssays 31, 1150–1160 (2009).

Focking, M. et al. Proteomic investigation of the hippocampus in prenatally stressed mice implicates changes in membrane trafficking, cytoskeletal, and metabolic function. Dev. Neurosci. 36, 432–442 (2014).

Gouvea-Junqueira, D. et al. Novel treatment strategies targeting myelin and oligodendrocyte dysfunction in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 11, 379 (2020).

Ikawa, T., Sato, M., Oh-Hashi, K., Furuta, K. & Hirata, Y. Oxindole-curcumin hybrid compound enhances the transcription of gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 896, 173898 (2021).

Nucifora, L. G. et al. Reduction of plasma glutathione in psychosis associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in translational psychiatry. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1215 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Catts, V. S. & Shannon, W. C. Lower antioxidant capacity in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 52, 690–698 (2018).

Tsugawa, S. et al. Glutathione levels and activities of glutathione metabolism enzymes in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychopharmacol. 33, 1199–1214 (2019).

Hanzawa, R. et al. No association between glutathione-synthesis-related genes and Japanese schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 65, 39–46 (2011).

Berry, T., Abohamza, E. & Moustafa, A. A. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Focus on the transsulfuration pathway. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 219–232 (2020).

Berk, M. et al. N-acetyl cysteine as a glutathione precursor for schizophrenia—A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 361–368 (2008).

Gorny, M., Bilska-Wilkosz, A., Iciek, M., Rogoz, Z. & Lorenc-Koci, E. Treatment with aripiprazole and N-acetylcysteine affects anaerobic cysteine metabolism in the hippocampus and reverses schizophrenia-like behavior in the neurodevelopmental rat model of schizophrenia. Febs J. 290, 5773–5793 (2023).

Quincozes-Santos, A. et al. Effects of atypical (risperidone) and typical (haloperidol) antipsychotic agents on astroglial functions. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry. Clin. Neurosci. 260, 475–481 (2010).

Dempster, K. et al. Early Treatment response in first episode psychosis: A 7-T magnetic resonance spectroscopic study of glutathione and glutamate. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 1640–1650 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participants for their cooperation in our study. We thank all the foundation projects that have supported us.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Suzhou (SS202069), Scientific and Technological Program of Suzhou (SKYD2023046), Key Discipline of Psychiatry in Suzhou (SZXK202521), Suzhou Gusu Health Talents Scientific Research Project ((2024)216), Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology Program (SKJYD2021134) and Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology Program (SYWD2024160).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XD designed the study and revised the article. Xiaoqian Fu and Xiaojia Fang were responsible for data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing and revision. LY, YL, FJ, GY, LY, XZ, YL and CL were responsible for manuscript writing and revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, X., Fang, X., Yang, L. et al. Alpha-actinin-1, profilin-1, filamin-A, integrin alpha-M and glutathione synthase were identified to be associated with cognitive and social functions of schizophrenia. Sci Rep 15, 42382 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26284-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26284-7