Abstract

The simplest Criegee intermediate (CH2OO), produced through the ozonolysis (O3) of ethylene in the Earth’s troposphere, plays a crucial role as a precursor in new particle formation (NPF) and secondary organic aerosols (SOA). Recent experimental and theoretical findings suggest that Criegee intermediate (CI) with organic acid, carbonyl, and amines is important for organic aerosol formation. However, the reaction of CI with imine, especially methanimine (CH2NH), has not been reported so far. The mechanism for CH2OO + CH2NH and CH2OO + CH2NH (+ H2O) was studied using ab initio/MD. Our results indicate that the rate constants for the CH₂OO + CH₂NH reaction fall within the range of CH2OO + CH2O and CH2OO + CH2CH2 reaction systems. The product branching ratio analysis indicates that cy-H2C(OO)NCH2 (IMn) and formimidic acid (NHCHOH) are the primary products in the gas phase reaction of CH2OO + CH2NH, irrespective of temperature. Notably, the involvement of water in the reaction facilitates the formation of significant pressure-dependent products, such as N-(hydroxymethyl)formamide (HMFn) and IMn. Born-Oppenheimer Molecular Dynamics (BOMD) simulations provide strong evidence for IMn formation in both the gas phase and the air-water interface, with the reaction proceeding more at the interface. Furthermore, BOMD simulations of CH2OO and CH2NH interactions on water droplet surfaces highlight the generation of water-mediated loop-structured products, including N-hydroxyethanimine (H2C = N-CH2-OOH) and HMHP (OH-CH2-OOH). This study highlights the potential significance of Criegee-Imine interactions in driving secondary aerosol formation, particularly in areas with elevated nitrogen-based emissions. The findings of this study may offer valuable insights into the CI-imine chemical processes in these regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Criegee intermediates (CIs) are highly reactive species formed during the ozonolysis of alkenes, and they play a central role in atmospheric oxidation and secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formation1,2,3,4. Once generated, CIs undergo unimolecular decomposition or bimolecular reactions with atmospheric species such as water, carbonyls, acids, and bases, thereby influencing radical production, organic acid formation, and aerosol growth5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Through these pathways, CIs contribute significantly to atmospheric composition, air quality, and climate forcing, making their kinetics and molecular dynamics critical for accurate atmospheric modeling.

Despite their importance, CI chemistry has been challenging to characterize due to its short lifetimes and the absence of direct precursors. A breakthrough came with the first direct detection of CH₂OO by Welz et al.15, which enabled laboratory and theoretical investigations of CI reactivity under tropospheric conditions16,17,18,19,20. Water vapor has been identified as a major atmospheric sink for CIs; however, competing processes, including reactions with carbonyls, SO₂, NO₂, and organic bases, remain significant21,22,23. These reactions link CI chemistry to sulfuric and nitric acid formation, particle nucleation, and climate-relevant transformations. Recent theoretical results have further suggested that CIs contribute to formaldehyde sinks24, yet the full atmospheric oxidation capacity of CIs and their dominant removal routes remain incompletely understood. Zhang and co-workers24 examined CH2OO and formaldehyde (HCHO) interactions, showing that reactions at the water droplet surface yield distinct loop-structured products.

Emerging evidence also highlights the role of multiphase and interfacial chemistry. Reactions at the air–water interface proceed through mechanisms distinct from those in the gas phase, underscoring the importance of aqueous environments in atmospheric transformations25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Molecular dynamics simulations and kinetic studies have revealed unique CI pathways involving water clusters, acids, and amines, expanding our understanding of SOA formation at interfaces. Among nitrogen-containing species, imines, particularly methanimine (CH2NH), remain underexplored in CI chemistry, despite their interstellar and atmospheric relevance. CH₂NH has been detected in both the interstellar medium and the Earth’s atmosphere, arising from diverse natural and anthropogenic sources including industrial emissions, sewage treatment, animal husbandry, biomass burning, oceanic biota, and protein degradation33,34,35. Once generated in the atmosphere, CH2NH undergoes extensive oxidation and degradation, producing secondary species that influence SOA nucleation, ozone depletion, and substance (N2O), yet their atmospheric fates remain poorly constrained35. Computational studies have recently provided mechanistic insights into amine/imine transformations involving CIs. Kumar et al. demonstrated that CI reactions with amines and imines proceed more efficiently at the air–water interface than in the gas phase, as revealed by Born–Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations28. Similarly, BOMD simulations of methylamine + CI interactions uncovered interfacial pathways inaccessible in the gas phase. Despite these advances, the role of imine chemistry in SOA nucleation, ozone depletion, and acid rain formation remains inadequately understood.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has investigated the reactivity of CIs with CH₂NH in either the gas phase or at the air–water interface. Given the established importance of both species in atmospheric oxidation and aerosol growth, understanding their interactions is essential. Here, we address this gap by combining quantum chemical calculations, statistical rate theory, and BOMD simulations to explore the reaction pathways of CH₂OO + CH₂NH in multiple environments. BOMD simulation data indicate that the CH2OO–CH2NH reaction at the air-water interface unfolds on a picosecond (ps) timescale. Unlike its gas-phase counterpart, this reaction proceeds through multiple stepwise mechanisms, contributing to the growing knowledge on interfacial Criegee processes occurring within the ps range. By examining both gas-phase and interfacial mechanisms, this study provides new insights into imine-CI-based aerosol formation, expands the chemical kinetic database required for atmospheric models, and advances our understanding of reactive nitrogen contributions to new particle formation and SOA growth in the troposphere.

Methodology

Electronic structure calculations

All gas-phase ab initio/DFT calculations were done using the Gaussian 16 software package36. The reactants, products, intermediates, and transition states involved in the reaction were optimized using the M06-2X37,38 with a 6–311 + + G(3df, 3pd) basis set. To account for the van der Waals interactions between two species, Grimme’s empirical dispersion (GD3) corrections39 were used. Previous studies have shown that M06-2X/6–311 + + G(3df, 3pd) with dispersion correction is reliable in handling noncovalent interactions40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. The nature of the saddle point was confirmed by frequency analysis, where reactants and products showed all positive and transition states showed a single imaginary frequency. To improve energy accuracy, single-point energy calculations were performed at the CCSD(T)/6–311 + + G(3df, 3pd) level. This dual-level scheme, CCSD(T)/6–311 + + G(3df,3pd)//M06-2X/6–311 + + G(3df,3pd), has been validated in previous benchmark studies42,43,44,45,46,47. Comparable work has shown that Minnesota functionals (M11) combined with CCSD(T) calculations can reproduce thermochemistry within ≤ 1 kcal mol⁻¹ for atmospheric systems49,50,51,52. Accordingly, M06-2X was selected as a computationally efficient and accurate method for modeling the gas-phase CI + CH₂NH reaction.

Chemical kinetics analysis

All the chemical kinetics calculations were carried out using the MultiWell Program53,54,55. For pressure-dependent kinetics, the Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel–Marcus (RRKM) theory combined with the master equation (ME) was employed, and the energy-dependent specific unimolecular rate constants, k(E), are provided in Eq. (1)

where h is Planck’s constant, \(\:\rho\:\)(E) is the density of states of the reactant molecule; \(\:{G}^{\ne\:}\left(E-{E}_{0\:\:}\right)\:\)is the sum of states of the transition state, and E0 is the reaction critical energy, which depends on angular momentum and \(\:{L}^{\ne\:}\) is the reaction path degeneracy. To avoid the repetition of previous work, the details of chemical kinetics analysis are given in the Supporting Information.

Molecular dynamics simulations

To investigate the formation of various products in different environments, including air, water, and the air-water interface arising from reactions between CI and CH2NH, we performed Born-Oppenheimer molecular dynamics (BOMD) simulations using the CP2K software package56. The simulations utilized the BLYP exchange-correlation functional57,58 as parameterized by Becke, Lee, Yang, and Parr, while Grimme’s functional was applied to account for long-range dispersion interactions39. The Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) norm-conserving pseudopotentials were used for core electrons, and the double-ζ valence polarization (DZVP) Gaussian basis set was employed for valence electrons59. Energy cutoffs were set at 280 Ry for the plane-wave and 40 Ry for the Gaussian basis set60,61. The simulations were conducted in the NVT ensemble under constant volume and temperature (300 K), with a time step of 0.5 femtoseconds (fs). Periodic supercells were separated by a vacuum layer of 15 Å in all directions to minimize interactions between images. The initial structure for the gas-phase BOMD simulation was derived from the pre-reactive complex between CI and CH2NH, identified through DFT-based quantum chemical calculations. For the air-water interface reaction, a water droplet containing 191 water molecules was pre-optimized at 300 K for 6.0 ps62, following the methodology established in previous20,23,25,63. Subsequently, CH2OO and CH2NH molecules were strategically positioned at different locations on the water droplet to initiate BOMD simulations. To ensure robust results and minimize the influence of initial structural variations, 10 and 20 distinct configurations were explored for the gas-phase and air-water interface reactions, respectively.

Results and discussion

Energy profile for CH2OO + CH2NH

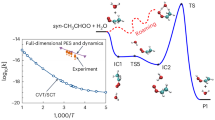

Figure 1 displays the potential energy surface (PES) for the CH2OO + CH2NH. The energies of all stationary points, including reactants, cyclic intermediates cy-H2C(OO)NCH2 (IMn), and transition states (TSs), are given in Supporting Information Table S1, and Cartesian coordinates for all geometries are given in Supporting Information Table S2. The optimized structures of all the stationary points are shown in Figure S1.

The reaction begins with the formation of a weak van der Waals complex, followed by a 1,3-cycloaddition that yields intermediate IMn, releasing 55.7 kcal mol⁻¹. Subsequently, IMn can undergo a 1,4-H shift to produce N-(hydroxymethyl)formamide (HMFn), with an associated energy release of approximately 134 kcal mol⁻¹. It should be noted here that the HMFn shows the most stable structure on the PES. Alternatively, IMn can decompose through a high barrier transition state to form formimidic acid and formaldehyde, and HMFn can decompose to formamide and formaldehyde. The PES for this reaction is consistent with similar reactions involving CH2OO + HCHO24 and CH2OO + CH2CH264,65 confirming the reliability of the results. The enthalpy values obtained in their computations are also provided in the supporting information in Table S1.

Zero-point corrected potential energy surface for the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction. The structural details are shown in Supporting Information Figure S1.

Energy profile for CH2OO + CH2NH (+ H2O)

We applied similar reaction pathways for single water-catalyzed reactions, as outlined in Energy profile for CH2OO + CH2NH. The PES for the effect of water on the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction is shown in Fig. 2. The optimized structures with bond length (in Å) are shown in Figure S2, and optimized cartesian coordinates are provided in Supporting Information Table S2. The reaction starts with the formation of an intermolecular hydrogen-bonded complex (CH2OO···CH2NH···H2O), stabilizing the structure by −12.3 kcal mol− 1. As shown in Fig. 2, this complex is stabilized by two hydrogen bonds: one between the nitrogen atom of CH2NH and a hydrogen atom of H₂O (1.85 Å), and another between the oxygen atom of H₂O and a hydrogen atom of CH2OO. This complex then undergoes a 1,3-cycloaddition, forming the intermediate IMn···H2O, which is −59.2 kcal mol− 1 more stable than the uncatalyzed structure. In this structure, three hydrogen bonds are established: one between the nitrogen atom of the five-membered ring IMn and a hydrogen atom of H2O (1.98 Å), and two involving terminal hydrogen atoms of the IMn with oxygen atoms of H2O (2.53 Å and 2.56 Å). Similar to the uncatalyzed pathway, the water-assisted IMn can decompose through a 1,4 H-shift to form a hydrogen-bonded N-(hydroxymethyl)formamide (HMFn···H2O) six-membered cyclic structure, releasing 135.7 kcal mol− 1. In HMFn···H2O, three hydrogen bonds are observed between the central N atom of HMFn with H atom H2O (2.58 Å), the terminal N atom of HMFn with H atom H2O (2.15 Å), and H atom HMFn with O atom of H2O (2.41 Å). Additionally, IMn···H2O can decompose to form formimidic acid (OH-CH = NH) and formaldehyde (HCHO) with water via a high barrier transition state (TSdn···H2O). Formimidic acid (OH-CH = NH) and formaldehyde (HCHO) with H2O can also be formed from the decomposition of HMFn···H2O through TSHMF1n···H2O.

This reaction step is energetically more favorable than the former one. HMFn···H2O can alternatively decompose to formamide (CHONH2) and formaldehyde (HCHO) with H2O in a similar way as discussed in energy profile for CH2OO + CH2NH. Overall, water-assisted structures are more stable due to the hydrogen bonding, enhancing their stability compared to their free counterparts. The PES for the water-assisted reaction is consistent with its counterpart reaction, CH2OO + CH2CH2 (+ H2O), confirming the reliability of the results as shown in Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4.

BOMD analysis

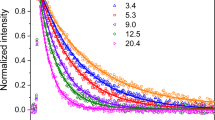

Formation of IMn

To further investigate the bonding and structural variations in the CI + CH2NH reaction, we conducted BOMD simulations. As shown in Fig. 3, the CH2OO and CH2NH are separated by a distance of 3.0 Å in the initial geometry subjected to BOMD simulation. The reaction between CH2OO and CH2NH was initiated by forming a stable five-membered like CH2OO⋯CH2NH van der Waal complex, formed at 1.5 ps. The bond lengths of C1-N1 and C2-O2 in the van der Wall interacted complex are around 2.39 Å and 2.77 Å in this transition state-like structure. Subsequently, the bond lengths of C1-N1 and C2-O2 bonds are further reduced to 1.48 Å and 1.52 Å after 1.6 ps.

It leads to forming a stable five-membered ring structure named IMn, which remains stable during further BOMD simulation. The time scales of this CH2OO + CH2NH reaction are comparable to those of the CH2OO and CH2O reaction for the formation of a five-membered transition state-like geometry (at 1.55 ps) and a CH2OO-CH2O-based five-membered ring (at 1.57 ps) of a previous study24.

Additionally, we investigated the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction at the air-water interface, as illustrated in Fig. 3b. This reaction follows a mechanistic pathway similar to its gas-phase counterpart. When CH2OO and CH2NH were positioned at the water droplet surface, the distance between them gradually decreased and stabilized after 0.7 ps. We observed that the N1 of CH2NH was first bonded to the C1 of CH2OO, followed by the formation of a C2-O2 bond at 0.85 ps. It leads to the formation of IMn with the stable C1-N1 and C2-O2 bond lengths that vary around 1.52 Å and 1.77 Å, respectively. Similar results were found for CH2OO and CH2O reactions for forming the stable complex at 0.75 ps and CH2OO-CH2O-based five-membered ring at 0.82 ps on the water droplet. Notably, IMn remains stable throughout the BOMD simulation at the air-water interface24. IMn formation from the reaction between CH2OO and CH2NH occurs more rapidly at the air-water interface than in the gas phase, indicating that the solvation environment at microdroplet interfaces enhances its formation.

Water-mediated product

This section comprehensively describes the interfacial water-mediated products of CH2OO and CH2NH reaction. We have observed N-hydroxyethanimine (H2C = N-CH2-OOH) as the primary product, as it forms in 14 out of 20 BOMD simulations due to the reaction between CH2OO and CH2NH through the water mediation. The results are presented in Fig. 4. Unlike gas-phase and air-water interface reactions, the CH2OO and CH2NH reactants come closer and form CH2NH-CH2OO by forming a new C1-N1 bond between the C1 of CH2OO and N1 of CH2NH at 1.3 ps (see Fig. 4a).

The CH2NH-CH2OO involved in the formation of two hydrogen bonds (HBs) between NH⋯OH2 (HB1) and OH2⋯OOCH2 (HB2), with one water molecule from the interfacial water droplet, results in the CH2OO⋯CH2NH⋯H2O loop structure at 2 ps. At this point, the NH⋯OH2 and OH2⋯OOCH2 hydrogen bond lengths are around 1.56 Å and 1.68 Å, respectively. These bond lengths are further stabilized, reaching 1.3 Å (HB1, NH⋯OH2) and 1.5 Å (HB2, OH2⋯OOCH2) at 2.2 ps. We observed that the H from NH of CH2NH is transferred to the interfacial H2O molecule and forms the CH2N-CH2OO−⋯ H3O+ complex at 2.21 ps. The proton from the hydronium (H3O+) ion swiftly transferred to the terminal O atom of CH2OO and led to the formation of H2C = N-CH2-OOH at 2.25 ps. The C1-N1 bond stabilization, the formation of new hydrogen bonds, and the transfer of NH and H2O hydrogen atoms at the respective time scales can also be seen in Fig. 4b. Overall, the water molecule was utilized as the mediator for the proton transfer process from the NH group of CH2NH to the terminal O atom of CH2OO to form the H2C = N-CH2-OOH as presented in Fig. 4c. These results are in accordance with the CH3CHOO and CH3NH2 reaction, where the transfer of NH hydrogen to the O atom of anti-CH3CHOO leads to the dominant product27.

In addition, we have also observed hydroxymethyl hydroperoxide (OH-CH2-OOH) as another product formation from 6 out of 20 BOMD simulations, as depicted in Fig. 5. Two H2O molecules from the interfacial water surface form OH-CH2-OOH during the reaction between CH2OO and CH2NH. In detail, when the CH2OO and CH2NH were introduced at the air-water interface (0.0 ps), the CH2OO molecule rapidly interacted with the water surface. In comparison, the CH2NH molecule gradually shifted away from the reaction center at 2.0 ps, as shown in Fig. 5.

The CH2OO molecule interacts with one of the water molecules of the water droplet (see at 2.1 ps) and forms a C1-O3 bond at 2.12 ps. Later, H2O-CH2OO forms a loop-structured complex to facilitate the proton transfer reaction at 2.15 ps. The two water and CH2OO molecules formed a loop structure through the C1⋯O3⋯H1⋯O4⋯H2⋯O2 atoms. Here, one of the water molecules is directly involved in forming the OH-CH2-OOH and the other is a mediator for the proton transfer process. Different reaction time scales and the corresponding molecular geometries are presented in Fig. 5b. Overall, the complete reaction occurred within 2.15 ps and led to the formation of OH-CH2-OOH by the mechanistic pathway, as shown in Fig. 5c. For comparison, the dynamic trajectories and varying bond lengths for the cyclic ozonide formation from the CH2OO and CH2O reaction at the air-water interface are shown in Supporting Information Figure S5.

Rate constants calculation

The rate constants and branching ratios (BR) provide important information for understanding atmospheric reactions. The product distribution of the multi-well CH2OO + CH2NH reaction, as well as temperature and pressure-dependent rate constants and BR, were evaluated using the RRKM/ME simulation. The rate constants within a temperature range of 200–400 K for the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction, as treated by the ME at 1 atm pressure, are shown in Fig. 6a. It shows that the rate constant increases constantly with the temperature until the maximum temperature is reached. This indicates that the temperature positively affects the rate constants, which are similar to the reactions of CH2OO + C2H4 and CH2OO + HCHO24,64. The calculated rate constant at 1 atm pressure and 298 K is predicted to be 2.00 × 10− 14 cm3 molecule− 1 s− 1. The rate constants are also compared with similar electronic systems, for example, CH2OO + C2H4 (~ 4 × 10− 15 cm3 molecule− 1 s− 1) and CH2OO + HCHO (5.13 × 10− 11 cm3 molecule− 1 s− 1, ~ 10− 12 cm3 molecule− 1 s− 1)24,65. As shown in Fig. 6, the rate constant of the two reactions (CH2NH and CH2CH2) increases with temperature and shows a positive temperature effect. However, in the case of CH2O, it shows negative temperature dependence. Our calculated value is between the reaction systems and shows close to the behavior of the CH2CH2 system. Our calculated value for CH2OO + CH2NH (+ H2O) decreases the overall rate constant by a factor of 4 at room temperature and by a factor of 3 at high temperature. The computed rate constant for the CH2OO + CH2NH (+ H2O) reaction at 1 atm pressure with 298 K at [H2O] = 7.1 × 1017 molecule/cc at 100% relative humidity is around 1.32 × 10− 18 cm3 molecule− 1 s− 1. This finding aligns with previous studies on similar water-based reactions41. This result is consistent with the water-assisted reaction CH2OO + CH2O. In general, the effective rate constants for water-assisted reactions are 3 to 4 orders of magnitude lower than those of water-free reactions (see Fig. 6b). Analysis indicates that the water-assisted gas-phase CH2OO + CH2NH reaction does not accelerate the process, as the dominant water-assisted pathway is highly dependent on water concentration. Consequently, the overall reaction rate constants are lower. The presence of water enables pressure-dependent product formation (e.g., RC, HMFn, IMn) through hydrogen-bonded water-bridged transition states. Quantum chemical studies of Criegee intermediate reactions with water monomers and dimers have shown that catalyzed structures involve multiple hydrogen bonds and pre-reaction complexes, which are more ordered than the corresponding uncatalyzed transition states66,67,68,69,70,71. The increased structural ordering results in a negative activation entropy (ΔS‡), reducing the pre-exponential factor in transition-state theory. As a consequence, even though ΔH‡ is reduced by water catalysis, the overall activation free energy (ΔG‡ = ΔH‡ – TΔS‡) remains comparable or higher, leading to slower net reaction rates under typical atmospheric conditions.

The branching ratios of different products formed during the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction are presented in Fig. 7. It shows that the IMn and NHCHOH are the dominant products of the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction at any temperature. It further shows that the NHCHOH is a major product at low pressure (0.001–0.1 atm) while IMn is major in the high-pressure (0.1–1000 atm) range. The concentration of unreacted CH2OO and CH2NH (i.e., CH2OO + CH2NH) species increases with the temperature, irrespective of the pressure. On the other hand, the presence of water reaction, i.e., CH2OO + CH2NH (+ H2O), leads to different major products at different pressures and temperatures. For example, the HMFn and IMn are the major products in the 0.001–0.1 atm pressure, IMn is only the leading product in the 0.1–10 atm pressure and IMn are the major products in the 10–1000 atm pressure at 200 K. A gradual shift in the dominance of HMFn for a higher-pressure range over the IMn was observed with increasing temperature. The concentration of unreactive CH2OO, CH2NH, and H2O species increases with the temperature, similar to that of the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction.

Atmospheric implications

By comparing our calculated rate constant for the CI + imine reaction (∼10⁻¹⁴ cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹) with faster competing reactions, such as CH2OO + HNO3 (~ 10⁻¹⁰ cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹) and CH2OO + CH2O (~ 10⁻¹² cm³ molecule⁻¹ s⁻¹), we summarize that the CI–imine pathway is unlikely to compete under general atmospheric conditions. Nonetheless, CI reactions with other species, including ethylene and amines, are also relatively slow and may become relevant in specific environments, such as biomass-burning plumes, where amine and imine concentrations are elevated. As discussed in the earlier section, the ozonolysis of ethylene plays a crucial role in the formation of secondary organic aerosols (SOA) in the atmosphere72,73,74,75. Amine-based oligomers have been identified as key components of SOA, similar to the products of this process28. However, their exact identities and formation pathways of these nitrogen-containing species remain unclear. Our calculations and BOMD simulations, which incorporate both gas-phase and air–water interface chemistry, suggest that Criegee intermediates (CIs) can react with CH₂NH to produce nitrogen-containing compounds, including IMn and NHCHOH in the gas phase. Even if its steady-state concentration of NHCHOH is low, formimidic acid could act as a reactive intermediate linking reduced nitrogen species with toxic products like HNCO (isocyanic acid) and HCN. Since HNCO is a toxic, carcinogenic compound found in biomass burning emissions and urban air, NHCHOH may represent a hidden precursor in atmospheric nitrogen chemistry.

At the air–water interface, these reactions may also yield species such as H2C = N-CH2-OOH and hydroxymethyl hydroperoxide (OH-CH2-OOH). As proposed in Kumar and Francisco27, these products can further decompose into H2C = N-CH2-O and OH-CH2O, generating OH radicals that serve as key intermediates in SOA formation, radical propagation, and cloud-related chemical processes. The newly identified nitrogen-containing compounds may therefore contribute to SOA formation and new particle formation (NPF) under these conditions74,75. In addition to their role in SOA formation, products of Criegee–imine reactions may participate in important atmospheric sink pathways. Recent studies have shown that nitrogen-containing organics derived from amine oxidation can efficiently partition into the particle phase, where they influence nucleation and particle growth27,28. Such multiphase chemistry can enhance NPF and stabilize clusters containing both organic and inorganic acids. The fate of these products is highly environment-dependent: while gas-phase reactions are dominated by unimolecular decomposition and bimolecular reactions with common oxidants, at the air–water interface, reactive intermediates may follow alternative pathways that enhance the incorporation of nitrogen-containing species into aqueous aerosols74,75. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating CI–imine chemistry into atmospheric models, particularly those addressing nitrogen-driven SOA formation and multiphase particle growth. Overall, our computational results provide a mechanistic basis that complements ongoing experimental and modeling studies and serves as a foundation for more quantitative investigations of nucleation processes and atmospheric sinks involving nitrogen-containing CI.

Conclusions

In this work, we thoroughly examined the mechanistic details of the water’s effect on the CH2OO + CH2NH reaction using the CCSD(T)//M06-2X level of theory and ab initio/MD simulation. Our study provides insights into the intricate chemistry of Criegee intermediates (CIs) and imines, revealing pivotal reaction dynamics critical to urban atmospheric processes. The branching ratio analysis confirms that IMn and NHCHOH are the predominant products of the gas phase formation. Notably, the presence of water drives the formation of pressure-dependent products such as RC, HMFn, and IMn, but the reaction rate is slower due to the lower entropic factor. Gas-phase single water “does nothing” to remove these intermediates in the atmosphere — its reaction is too slow compared to other naked reaction systems. State-of-the-art BOMD simulations validate the emergence of IMn, featuring CH₂OO and CH₂NH-derived five-membered rings in both the gas phase and at the air-water interface. Interestingly, reactions at the interface proceed with significantly enhanced rates. Furthermore, interactions between CH2OO and CH2NH on water droplet surfaces yield loop-structured compounds, including new compounds such as H₂C = N-CH2-OOH and OH-CH₂-OOH, which can be key responsible intermediates for SOA formation, radical chemistry, and cloud processes. These findings advance our understanding of the chemical behavior of CIs and imines in moisture-rich urban atmospheres, such as fog or aerosols, offering crucial implications for atmospheric chemistry in pollution-heavy regions where more nitrogen-containing compounds are emitted.

Data availability

All the data generated in this paper are discussed in the paper and given in the Supporting Information.

References

Taatjes, C. A., Shallcross, D. E. & Percival, C. J. Research frontiers in the chemistry of Criegee intermediates and tropospheric ozonolysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 1704–1718 at (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cp52842a

Dash, M. R., Muthiah, B. & Mishra, S. S. Formation of alkoxymethyl hydroperoxides and alkyl formates from simplest Criegee intermediate (CH2OO) + ROH (R = CH3, CH3CH2, and (CH3) 2CH) reaction systems. Theor. Chem. Acc. 143, 29 (2024).

Johnson, D. & Marston, G. The gas-phase ozonolysis of unsaturated volatile organic compounds in the troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 699–716 (2008).

Criegee, R. Mechanism of ozonolysis. Angew Chemie Int. Ed. Engl. 14, 745–752 (1975).

Samanta, K., Beames, J. M., Lester, M. I. & Subotnik, J. E. Quantum dynamical investigation of the simplest Criegee intermediate CH2OO and its O–O photodissociation channels. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 134303 (2014).

Barber, V. P. et al. Four-carbon Criegee intermediate from isoprene ozonolysis: Methyl vinyl ketone oxide synthesis, infrared spectrum, and OH production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10866–10880 (2018).

Kidwell, N. M., Li, H., Wang, X., Bowman, J. M. & Lester, M. I. Unimolecular dissociation dynamics of vibrationally activated CH3CHOO Criegee intermediates to OH radical products. Nat. Chem. 8, 509–514 (2016).

Green, A. M., Barber, V. P., Fang, Y., Klippenstein, S. J. & Lester, M. I. Selective deuteration illuminates the importance of tunneling in the unimolecular decay of Criegee intermediates to hydroxyl radical products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 12372–12377 (2017).

Liu, F., Beames, J. M., Petit, A. S., McCoy, A. B. & Lester, M. I. Infrared-driven unimolecular reaction of CH3CHOO Criegee intermediates to OH radical products. Science. 345(80), 1596–1598 (2014).

Lester, M. I. & Klippenstein, S. J. Unimolecular decay of Criegee intermediates to OH radical products: prompt and thermal decay processes. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 978–985 (2018).

Leather, K. E. et al. Acid-yield measurements of the gas-phase ozonolysis of Ethene as a function of humidity using chemical ionisation mass spectrometry (CIMS). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 469–479 (2012).

Mauldin Iii, R. L. et al. A new atmospherically relevant oxidant of sulphur dioxide. Nature 488, 193–196 (2012).

Berndt, T. et al. H2SO4 formation from the gas-phase reaction of stabilized Criegee intermediates with SO2: influence of water vapour content and temperature. Atmos. Environ. 89, 603–612 (2014).

Huang, H. L., Chao, W. & Lin, J. J. M. Kinetics of a Criegee intermediate that would survive high humidity and may oxidize atmospheric SO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 10857–10862 (2015).

Welz, O. et al. Direct kinetic measurements of Criegee intermediate (CH2OO) formed by reaction of CH2I with O2. Sci. (80-). 335, 204–207 (2012).

Liu, F., Beames, J. M., Green, A. M. & Lester, M. I. UV spectroscopic characterization of dimethyl- and ethyl-substituted carbonyl oxides. J. Phys. Chem. A. 118, 2298–2306 (2014).

Beames, J. M., Liu, F., Lu, L. & Lester, M. I. UV spectroscopic characterization of an alkyl substituted Criegee intermediate CH3CHOO. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 244307 (2013).

Lin, H. Y. et al. Infrared identification of the Criegee intermediates syn- and anti-CH3CHOO, and their distinct conformation-dependent reactivity. Nat. Commun. 6, 7012 (2015).

Chao, W., Hsieh, J. T., Chang, C. H. & Lin, J. J. M. Direct kinetic measurement of the reaction of the simplest Criegee intermediate with water vapor. Science. 347(80), 751–754 (2015).

Zhu, C. et al. New mechanistic pathways for Criegee–water chemistry at the air/water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11164–11169 (2016).

Welz, O. et al. Rate coefficients of C1 and C2 Criegee intermediate reactions with formic and acetic acid near the collision limit: direct kinetics measurements and atmospheric implications. Angew Chemie - Int. Ed. 53, 4547–4550 (2014).

Taatjes, C. A. et al. Direct measurement of Criegee intermediate (CH 2 OO) reactions with acetone, acetaldehyde, and hexafluoroacetone. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 10391–10400 (2012).

Chhantyal-Pun, R. et al. Criegee intermediates: production, detection and reactivity. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 39, 385–424 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Multiple evaluations of atmospheric behavior between Criegee intermediates and HCHO: Gas-phase and air-water interface reaction. J. Environ. Sci. 127, 308–319 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Near-barrierless ammonium bisulfate formation via a loop-structure promoted proton-transfer mechanism on the surface of water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 1816–1819 (2016).

Zhong, J. et al. Mechanistic insight into the reaction of organic acids with SO3 at the air–water interface. Angew Chemie. 131, 8439–8443 (2019).

Kumar, M. & Francisco, J. S. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of Criegee-amine chemistry in the gas phase and aqueous surface environments. Chem. Sci. 10, 743–751 (2019).

Kumar, M., Li, H., Zhang, X., Zeng, X. C. & Francisco, J. S. Nitric acid–amine chemistry in the gas phase and at the air–water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6456–6466 (2018).

Kumar, M., Zhong, J., Zeng, X. C. & Francisco, J. S. Reaction of Criegee intermediate with nitric acid at the air–water interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4913–4921 (2018).

Tang, B. & Li, Z. Molecular mechanisms and atmospheric implications of Criegee intermediate–alcohol chemistry in the gas phase and aqueous surface environments. J. Phys. Chem. A. 124, 8585–8593 (2020).

Liu, J., Liu, Y., Yang, J., Zeng, X. C. & He, X. Directional proton transfer in the reaction of the simplest Criegee intermediate with water involving the formation of transient H3O+. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 3379–3386 (2021).

Kumar, M. & S Francisco, J. Ion pair particles at the air–water interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 12401–12406 (2017).

Bernstein, M. P., Bauschlicher, C. W. Jr & Sandford, S. A. The infrared spectrum of matrix isolated aminoacetonitrile, a precursor to the amino acid Glycine. Adv. Sp Res. 33, 40–43 (2004).

Koch, D. M., Toubin, C., Peslherbe, G. H. & Hynes, J. T. A theoretical study of the formation of the aminoacetonitrile precursor of Glycine on icy grain mantles in the interstellar medium. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 2972–2980 (2008).

Nielsen, C. J., Herrmann, H. & Weller, C. Atmospheric chemistry and environmental impact of the use of amines in carbon capture and storage (CCS). Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6684–6704 (2012).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16. at (2016).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06 functionals and 12 other functionals (T. Theor. Chem. Acc. 119, 525 at (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-007-0401-8

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 157–167 (2008).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate Ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Ali, M. A., Dash, M. R. & Al Maieli, L. M. Catalytic effect of CO2 and H2O molecules on • CH3 + 3O2 reaction. Catalysts. 12, 699 (2022).

Ali, M. A., Balaganesh, M. & Lin, K. C. Catalytic effect of a single water molecule on the OH + CH 2 NH reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 4297–4307 (2018).

Ali, M. A. Computational studies on the gas phase reaction of Methylenimine (CH2NH) with water molecules. Sci. Rep. 10, 10995 (2020).

Ali, M. A., Balaganesh, M., Al-Odail, F. A. & Lin, K. C. Effect of ammonia and water molecule on OH + CH3OH reaction under tropospheric condition. Sci. Rep. 11, 12185 (2021).

Dash, M. R. & Ali, M. A. Effect of a single water molecule on˙ CH 2 OH + 3 O 2 reaction under atmospheric and combustion conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 1510–1519 (2022).

Ali, M. A., Balaganesh, M. & Jang, S. Can a single water molecule catalyze the OH + CH2CH2 and OH + CH2O reactions? Atmos. Environ. 207, 82–92 (2019).

Dash, M. R. & Ali, M. A. Can a single ammonia and water molecule enhance the formation of methanimine under tropospheric conditions? Kinetics of• CH2NH2 + O2 (+ NH3/H2O). Front. Chem. 11, 1243235 (2023).

Ali, M. A. & Balaganesh, M. Effect of formic acid on O 2 + OH˙ CHOH→ HCOOH + HO 2 reaction under tropospheric condition: kinetics of Cis and trans isomers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 9965–9978 (2023).

Ali, M. A. & Saswathy, R. Formation of acetonitrile (CH3CN) under cold interstellar, tropospheric and combustion mediums. Sci. Rep. 14, 22313 (2024).

Zhang, Y. Q., Xia, Y. & Long, B. Quantitative kinetics for the atmospheric reactions of Criegee intermediates with acetonitrile. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 24759–24766 (2022).

Jiang, H. et al. Criegee intermediates significantly reduce atmospheric (CF3) 2CFCN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 12263–12272 (2025).

Long, B., Bao, J. L. & Truhlar, D. G. Atmospheric chemistry of Criegee intermediates: unimolecular reactions and reactions with water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14409–14422 (2016).

Xia, Y. et al. Large pressure effects caused by internal rotation in the s-cis-syn-acrolein stabilized Criegee intermediate at tropospheric temperature and pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4828–4838 (2022).

Barker, J. R. MultiWell-2023 software. Ann arbor: university of michigan. MultiWell-2023 software. Ann Arbor Univ. Michigan (2023).

Barker, J. R. Multiple-Well, multiple-path unimolecular reaction systems. I. MultiWell computer program suite. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 33, 232–245 (2001).

Barker, J. R. Energy transfer in master equation simulations: A new approach. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 41, 748–763 (2009).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: an electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package—Quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the colle–salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 37, 785–789 (1988).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 1703 (1996).

Hartwigsen, C., Gœdecker, S. & Hutter, J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B. 58, 3641 (1998).

VandeVondele, J. & Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983).

Kumar, M., Zhong, J., Francisco, J. S. & Zeng, X. C. Criegee intermediate–hydrogen sulfide chemistry at the air/water interface. Chem. Sci. 8, 5385–5391 (2017).

Sun, C., Xu, B., Lv, L. & Zhang, S. Theoretical investigation on the reaction mechanism and kinetics of a Criegee intermediate with ethylene and acetylene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 16583–16590 (2019).

Jalan, A., Allen, J. W. & Green, W. H. Chemically activated formation of organic acids in reactions of the Criegee intermediate with aldehydes and ketones. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 16841–16852 (2013).

Lin, L. C. et al. Competition between H 2 O and (H 2 O) 2 reactions with CH 2 OO/CH 3 CHOO. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 4557–4568 (2016).

Lin, L. C. & Takahashi, K. Will (CH3) 2COO survive in humid conditions? J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 63, 472–479 (2016).

Lin, J. J. M. & Chao, W. Structure-dependent reactivity of Criegee intermediates studied with spectroscopic methods. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 7483–7497 (2017).

Kumar, M., Sinha, A. & Francisco, J. S. Role of double hydrogen atom transfer reactions in atmospheric chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 877–883 (2016).

Ryzhkov, A. B. & Ariya, P. A. A theoretical study of the reactions of parent and substituted Criegee intermediates with water and the water dimer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 5042–5050 (2004).

Sakamoto, Y., Inomata, S. & Hirokawa, J. Oligomerization reaction of the Criegee intermediate leads to secondary organic aerosol formation in ethylene ozonolysis. J. Phys. Chem. A. 117, 12912–12921 (2013).

Hawkins, L. N. et al. Formation of semisolid, oligomerized aqueous SOA: lab simulations of cloud processing. Environ. Sci. \& Technol. 48, 2273–2280 (2014).

Kirkby, J. et al. Atmospheric new particle formation from the CERN CLOUD experiment. Nat. Geosci. 16, 948–957 (2023).

Bianchi, F. et al. Highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOM) from gas-phase autoxidation involving peroxy radicals: A key contributor to atmospheric aerosol. Chem. Rev. 119, 3472–3509 (2019).

Pöschl, U. & Shiraiwa, M. Multiphase chemistry at the atmosphere–biosphere interface influencing climate and public health in the anthropocene. Chem. Rev. 115, 4440–4475 (2015).

Acknowledgements

NVRN and MAA thank the Khalifa University of Science and Technology supercomputer facility in Abu Dhabi, UAE. MAA thanks Faculty Start-up grant #8474000461. MAA thanks the Center for Catalysis and Separations (CeCaS), Khalifa University of Science and Technology, for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.VRN : conceptualization, investigation, data curation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing the original draft. MRD: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing the original draft. MAA: conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dash, M.R., Nulakani, N.V.R. & Ali, M.A. Comprehensive assessment of atmospheric interactions between Criegee intermediate and simplest Imine (CH2NH) in gas and aqueous phase environments. Sci Rep 15, 42352 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26286-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26286-5