Abstract

Elevated levels of blood-based biomarkers such as neurofilament light chain (NfL) and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) are associated with poor neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). This study investigates the relationship between regional grey matter volume reduction and levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), NfL, NSE, and total-tau (t-tau) protein. This substudy of the Xe-Hypotheca trial included 110 patients randomized to receive either inhaled xenon with target temperature management (TTM) at 33 °C for 24 h (n = 55) or TTM alone (n = 55). Voxel-based morphometry was used to assess grey matter volume changes in MRI scans acquired 36–52 h and 10 days after OHCA in 45 survivors. Blood biomarkers were measured upon intensive care unit arrival and at 24, 48 and 72 h post-OHCA. NfL levels positively correlated with grey matter volume reduction in the thalamus and cingulate cortex at 24 h post-OHCA. T-tau showed more extensive pattern of significant correlations, increasing in both magnitude and spatial extent from baseline to 48 h post-OHCA. No significant biomarker–volume associations were observed for GFAP or NSE, and no treatment group differences were detected. Elevated NfL and t-tau levels were associated with region-specific grey matter volume reduction within the first 10 days after OHCA. Among the four biomarkers studied, t-tau demonstrated the strongest and most widespread associations, suggesting its potential as a marker for early ischemic grey matter volume reduction after OHCA. ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00879892, 13/04/2009.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is often complicated by high rate of in-hospital mortality, the rate ranges between 41 and 86% 1,2. Post-cardiac arrest brain injury is the most common cause of mortality and is the leading cause of long-term morbidity in resuscitated patients 3. Cardiac arrest can lead to long-term brain tissue atrophy, which is associated with cognitive impairment and delayed neurological deficits. 4.

Functional and structural changes in the brain following cardiac arrest have been studied by using various neuroimaging methods 5. Among these, voxel-based morphometry (VBM) method has emerged as a well-established in-vivo technique for detecting regional difference in brain tissue volume; it has been widely used in clinical research, including studies examining structural brain damage following cardiac arrest. Earlier VBM studies have revealed that survivors of cardiac arrest often exhibit significant long term grey matter volume loss in several brain regions, such as the anterior, medial, and posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, insular cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus 6,7,8,9. These reductions have been associated with neuropsychological impairments, including amnestic deficits and apathy 6. Furthermore, in a recent substudy of the Xe-Hypotheca trial involving the same patient cohort as the present study, we demonstrated the neuroprotective effect of xenon, evidenced by its ability to attenuate grey matter volume reduction in OHCA survivors 10.

Blood-based biomarkers, including glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neurofilament light chain (NfL), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and total-tau (t-tau), have gained recognition as indicators of variety of brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases 11,12,13,14,15,16. NSE is a glycolytic enzyme located mainly in neuronal cell bodies and released during neuronal cell injury including ischemia–reperfusion 17. GFAP is an intermediate-filament component of astrocytic cytoskeleton mainly expressed in the central nervous system, but also in non-myelinated Schwann cells and enteric glial cells 18. GFAP is also a part of intracellular neuroprotective system which is upregulated in astroglial activation related to brain tissue injury and is involved in several physiological, and pathophysiological functions including increased microglial activity due to secondary ischemia, regulation of neurotransmitter uptake and astrogliosis 18,19,20,21,22. NfL is a neuron cytoskeletal and axon-specific protein and is an indicator of axonal injury in several neurological diseases 23. Large, myelinated axons express high levels of neurofilaments and especially NfL 24. Tau is a heterogeneous group of structurally altering proteins, which are acting as a stabilizing component in axonal microtubules 25.

Numerous previous studies have reported promising results regarding the prognostic value of GFAP, NfL, NSE and t-tau in predicting clinical outcomes after OHCA 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Despite these findings, the most recent guidelines from the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) and European Council for Intensive Care treatment (EICISM) include only NSE in their prognostication protocol. Considering this, additional information is required before NfL, GFAP, or t-tau can be adopted in routine clinical practice 1,36.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the currently unestablished potential of GFAP, NfL, NSE and t-tau to detect grey matter volume reduction, as assessed by VBM, within 10 days of an OHCA.

Methods

Study design

The Xe-HYPOTHECA trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00879892, 13/04/2009) was a randomized 2-group single-blinded phase II clinical drug trial in two multipurpose intensive care units (ICU) in Finland; the trial was performed at Turku University Hospital between August 2009 and September 2014 and at Helsinki University Hospital between October 2012 and September 2014. The trial was primarily designed as a proof-of-concept study to assess whether xenon provides neuroprotection to human brain white matter following global ischemia caused by OHCA.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland on March 17, 2009 (approval number 10/2009/§65) and the institutional review boards of Helsinki University Hospital and the Finnish Medicines Agency. All patients’ next of kin or legal representatives gave written informed assent within four hours after hospital arrival. The patient’s family was informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, while also being made aware that any data collected up to that point could still be used for scientific purposes.

The protocol and main efficacy results of the Xe-Hypotheca trial has been published earlier 37. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study if they regained consciousness. An independent data and a safety monitoring committee reviewed the data after the enrolment of every four patients and after an interval of six months. The study was conducted according to good clinical practice and the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki guiding clinical drug research in human subjects 38.

Participants

Patient population consisted of comatose survivors of OHCA screened for the following inclusion criteria: (1) witnessed cardiac arrest, (2) ventricular fibrillation, (3) non-perfusing ventricular tachycardia, (4) presumed cardiac origin, (5) age 18–80 years, (6) start of resuscitation by emergency medical personnel within 15 min, (7) return of spontaneous circulation within 45 min, (8) decision for therapeutic hypothermia treatment by attending physician. In addition, in the current study, patients who underwent each of two MRI scans were considered as being eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria, the treatment protocol and neurological prognostication consensus used in decisions to withdraw life-sustaining treatment have been described earlier 37.

Randomization

Patients were allocated in 1:1 ratio with random block sizes of 4, 6, and 8 to receive either TTM (33 °C) alone for 24 h or inhaled xenon (LENOXe, Air Liquide Medical GmbH, Dusseldorf Germany) with a sub-anesthetic target concentration of 40% in oxygen/air combined with TTM (33 °C) for 24 h. The treatment assignment was randomly generated by a computer. Sequentially numbered sealed envelopes were used separately in the two centers for randomization, which was performed after the assent was granted. The personnel involved in the treatment of the patient could not be blinded due to practical and safety considerations, but the neurological endpoint evaluator and patients were blinded to the treatment.

Primary aim of the study

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of grey matter reduction assessed by VBM with multiple blood-based biomarkers including GFAP, NSE, NfL and t-tau collected upon ICU arrival and (T = 0) at 24, 48 and 72 h post-OHCA .

Imaging procedure

Patients were kept intubated and sedated until the first brain scan was performed. In both centers, the structural T1-weighted MRI data were acquired by a 3.0 T Magnetom Verio system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 12-channel head coil.

A three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence was used with a 1900 ms repetition time, 2.2 ms echo time, 900 ms inversion time, 9° flip angle, 200 Hz/Px bandwidth, 250 × 250 × 176 mm3 field-of-view, and 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3 resolution. Zero-interpolation filling was applied during image reconstruction so that images had 0.5 × 0.5 × 1.0 mm3 resolution.

Processing and analysis of structural MRI data

MRI data processing was conducted using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12.8.1) of the Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, Version 7771, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), running under Matlab (MathWorks, Inc.) (Fig. 1.) 39. The image quality control and preprocessing pipeline, optimized for longitudinal data, has been detailed in Hollmén et al. 10. For each participant, pairs of T1-weighted images were co-registered and segmented into tissue classes, including grey matter. Grey matter images were then nonlinearly normalized to the standard MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) brain space, with modulation applied to create voxel-wise grey matter volume maps. These grey matter images, with isotropic resolution of 1.5 mm, were smoothed with a 6 mm Gaussian kernel. Finally, for each patient, voxel-wise differences in grey matter volume between the first and second MRI scans were computed, with positive voxel values indicating grey matter volume loss between scans. These difference images were used in the statistical analysis, constrained within a grey matter mask.

Biochemical analysis

Blood samples for GFAP, NfL, NSE, and t-tau were collected at four timepoints (T), T0 at 0 h T24 at 24 h, T48 at 48 h, and T72 at 72 h after the OHCA. GFAP, NfL, and t-tau levels were measured using the Human Neurology 4-Plex A Assay (N4PA) on a HD-1 Single molecule array (Simoa) from Quanterix (Quanterix, Billerica, MA, USA). Calibrations were in duplicates and obvious outliers were masked before curve fitting. Samples were diluted fourfold and run in single samples. Results were compensated for dilution. NSE levels were measured with electrochemiluminescence immunoassay using Cobas e801 assay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The sample size of 110 patients was based on a power analysis of the fractional anisotropy values from brain MRI, i.e., the primary end point of the Xe-HYPOTHECA trial 37.

Because of highly skewed distributions and high variability of the biomarkers data, we employed natural log transformation of biomarker values. In this study, a between group difference of grey matter volume changes between the first and second scan was calculated. Initially, we assessed the relationship between grey matter volume loss and biomarker levels at each time point using separate statistical models for each biomarker. Statistical models for the VBM analyses were constructed and estimated using SPM12 software. Each model included a covariate of interest (biomarker levels) adjusted for following variables: total intracranial volume for both scans, age, gender, imaging site, treatment group, and the time interval between OHCA and the first MRI scan. The treatment group categorized based on presence or absence of xenon inhalation therapy was included in the model because prior findings from this cohort demonstrated a xenon treatment effect on grey matter volume loss 10. The time interval between OHCA and the first MRI (median 50.5 h, IQR10.5) was included as a covariate to account for its variability. Differences between the xenon and control groups in the association between grey matter volume loss and biomarker level were examined using ANCOVA, incorporating a similar set of covariates with an additional interaction term between the group and biomarker level. If a significant interaction was detected via a F-test, within-group multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the direction of the effect.

All models were estimated non-parametrically using the threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) method, which enhances sensitivity by considering both cluster size and voxel signal magnitude when calculating voxel-wise statistics 40. Default weightings for cluster extent (E = 0.5) and height (H = 2) were applied, with 5000 permutations used to generate the null distribution. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, corrected for family-wise error rate (FWER).

Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, background morbidity, resuscitation details, and clinical outcomes, were compared between groups using appropriate statistical tests: two-sample t-tests, Mann–Whitney U-tests, χ2 tests, or Fisher’s exact tests. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software for Windows (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

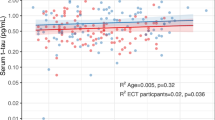

A total of 224 comatose OHCA survivors (aged 24 to 76 years) were screened for eligibility, and 110 patients were included into the main study (Fig. 2). Patients were randomly assigned to receive either TTM alone (n = 55) or TTM combined with inhaled xenon gas (n = 55). Of the 66 patients who survived and underwent both the first and second scan after OHCA, 45 patients fulfilled the quality criteria and were included in the grey matter volume analysis. The details of patient selection have been reported earlier 10. The first scan was carried out at a median of 51 h (interquartile range 46–56 h) and second scan in median of 10 (interquartile range 9–11) days. Demographical data, background morbidity, and resuscitation details of this patient population are shown in Table 1. Temporal patterns of the biomarkers are presented in Fig. 3, while descriptive median (IQR) values after natural logarithmic transformation are shown in Table 2. The corresponding original median (IQR) values are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Quartile boxplots of natural log-transformed GFAP, NfL, NSE, and t-tau biomarker levels measured at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post-OHCA. The boxplot whiskers represent 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR), and the corresponding median and IQR values are detailed in Table 2.

Regional grey matter reduction in different time points associated with biomarkers

Significant (p < 0.05, FWER-corrected, TFCE statistics) positive association between blood biomarker level and grey matter volume loss were obtained for NfL at 24 h post-OHCA and for t-tau at 0, 24 and 48 h post-OHCA (Fig. 4, Table 3). No significant results were obtained for GFAP and NSE. There were no significant differences in the relationship between grey matter volume loss and biomarker values across treatment groups for any biomarker measurement timepoint.

Significant (p < 0.05, FWER-corrected, TFCE statistics) clusters showing positive associations between grey matter volume loss and biomarker levels measured at different time points after OHCA (24 h for NfL; 0, 24 and 48 h for t-tau). The clusters (in red) are overlaid on a series of slices of the MNI structural brain template. The top row indicates the z coordinates of the slices (in mm). Hemispheres: L– left; R – right. Cluster peak locations and statistical values are detailed in Table 3.

Neurofilament light chain

Higher NfL levels at 24 h post-OHCA were correlated with increasing grey matter volume loss in the thalamus and anterior cingulate bilaterally, as well as in the posterior cingulate, precuneus, in the anterior temporal, and in the ventromedial frontal cortex of the left hemisphere (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

Total-tau

The areas of positive correlation between grey matter loss and t-tau levels progressively increased in their extent and magnitude from 0 to 48 h post-OHCA. Thus, for the initial (0 h) timepoint small local clusters were observed in the right anterior cingulate and lateral frontal areas. At the 24 h post-OHCA time point, the anterior cingulate was affected bilaterally and multiple right frontal areas, located in the frontal operculum and in the inferior frontal gyrus were observed. The most widespread pattern of the clusters was found for 48 h post-OHCA, where, in addition to the structures mentioned for the earlier timepoints, parts of the left occipital cortex (calcarine area and lingual gyrus), the bilateral precuneus along with the adjacent left posterior cingulate, the bilateral temporal region, the right anterior insular region, the left medial frontal region, the right central operculum, and the right thalamus were significantly involved (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

Discussion

The main finding was that blood-based biomarkers NfL and t-tau correlated significantly with a reduction of grey matter volume in specific brain regions during the early phase (first 10 days) post-OHCA. Notably, these associations were predominantly observed in the thalamus and cingulate cortex for NfL. In contrast, t-tau showed a more widespread pattern of significant correlations, increasing in both magnitude and spatial extent from baseline to 48 h post-OHCA. Regions showing significant volume reduction included the frontal, temporal and insular cortices, as well as also cingulate cortex and thalamus. No significant differences were found between treatment groups regarding the relationship between biomarker levels and grey matter volume loss.

In our study, levels of GFAP and NfL generally increased from 0 to 48 or to 72 h post-OHCA, whereas NSE and t-tau levels showed a decreasing trend over time. These patterns are consistent with previous studies involving patients with favorable outcomes (modified Ranking Scale scores of 0–3). In such patients, NSE levels typically remain stable or decline between 0 and 72 h, while t-tau levels also tend to decrease during this period, with delayed peaks mainly observed in patients with poor outcomes 35,41,42,43,44. In contrast, NfL levels tend to rise following cardiac arrest, including in patients with favorable outcomes; however, in these patients the increase is usually modest 27,28,33,35. Similarly, the temporal profile of GFAP in this cohort aligns well with previously reported results in patients with favorable outcomes 33,35. The present study cohort predominantly consisted of patients with favorable six-month outcomes, as detailed in our recent publication 10. In summary, six patients were comatose and intubated during the second scan, while all others were conscious. Of the 45 patients, four died before discharge and the remainder survived to six months. The median modified Rankin Scale scores were 0.5 [IQR, 0–2] in the xenon group and 0 [IQR, 0–0] in the control group (p = 0.04). An imbalance arose because initially seven xenon patients and two control patients underwent the second scan before death. Of these nine patients, four xenon patients and none in the control group had an acceptable image quality. Other non-surviving patients in both groups were already in poor clinical condition after OHCA and died before the scheduled second scan. This led to a skewed assessment of neurological outcome at six months, disadvantaging the xenon group, as non-survivors were present only in this group. Importantly, no differences in mRS were observed between groups in the full intention-to-treat population of 110 patients. Overall, our results regarding the temporal dynamics of these biomarkers are consistent with the existing literature on cardiac arrest survivors with favorable outcome.

Neurocognitive impairments affect approximately 34–50% of cardiac arrest survivors, including those classified as having a favorable neurological outcome 45,46,47,48,49. Among these impairments, memory deficits are most commonly reported, but impairments in attention and executive functioning are also frequently observed 46. Previously, Byron-Alhassan et al. demonstrated that regional grey matter volume reduction can occur even in patients with Cerebral Performance Category scores of 1 or 2 within four weeks following OHCA 7. This finding suggests that structural brain damage may be present even in patients with preserved or only mildly impaired cerebral function. In this context, our findings align with previously reported patterns of post-OHCA grey matter volume reduction 6,7,8,9,49.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between blood-based biomarkers and grey matter volume reduction following OHCA. Among the four biomarkers assessed, NfL and t-tau showed significant correlations with grey matter volume reduction during the first ten days following OHCA. Specifically, the NfL levels measured at 24 h post-arrest were positively correlated with grey matter reduction, with significant clusters identified bilaterally in the thalamus and anterior cingulate cortex, regions previously implicated in long-term volume reduction after OHCA 6,7,8. A recent study by Carlier et al. further emphasized the thalamus as a key region in post-cardiac arrest brain injury, demonstrating that structural damage one month after OHCA may contribute to subsequent cognitive decline 9. However, the study design of the present study did not include sensitive neurocognitive assessments, limiting our ability to directly correlate grey matter volume reduction with cognitive outcome.

NfL, GFAP and t-tau have been established as biomarkers of long-term neurodegeneration in patients with traumatic brain injury and Alzheimer’s disease 11,12,13,14,15,16. Current findings extend this evidence by suggesting that NfL and t-tau may reflect also short-term structural damage to grey matter, including the basal ganglia and cortical regions, even in patients with favorable neurological outcomes. Notably, this study identified a novel and extended pattern of correlation between t-tau and cortical volume reduction from baseline to 48 h post-OHCA. t-tau correlated significantly with grey matter volume loss primarily in the fronto-temporo-insular cortical regions, which are involved in behavior, cognition, memory, emotion, and motor control. Previous VBM and cortical thickness studies have also noted long-term grey matter reduction in these regions, including the caudate, insular, and various lateral cortical areas due to the hypoxic ischemic injury after OHCA 6,8,49. Our results suggest that t-tau may be the most promising of the four biomarkers currently studied for assessing the progression of ischemic grey matter volume reduction after OHCA. Further research is needed to evaluate the accuracy and utility of combining NfL and t-tau with early phase MRI to identify patients with risk for subsequent neurocognitive impairment after OHCA.

In this study, GFAP and NSE did not correlate with grey matter volume reduction. Notably, previous research has not established a clear correlation between NSE and grey matter volume loss, which also obtains in TBI. The absence of a correlation between GFAP and grey matter volume loss in our study may be attributed to differences in imaging time windows as compared with earlier studies in patient with TBI. The Xe-Hypotheca trial focused on short-term changes (0–72 h), whereas prior studies such as those by Newcombe et al., investigated long-term biomarker dynamics and their correlations with grey matter volume reduction extending from months to years, when the injury had evolved into its chronic phase 11. However, these earlier findings are somewhat inconsistent. For instance, Newcombe et al. reported that elevated NfL levels at eight months post-injury predicted grey matter volume reduction at five years, whereas GFAP did not correlate with long-term atrophy. Moreover, higher NfL levels at eight months were associated with increased annualized grey matter volume reduction over the subsequent five to nine years. In contrast, Shahim et al. found significant correlations between GFAP and grey matter volume reduction in patients with TBI 13. These divergent findings suggest that the temporal dynamics of biomarker release and the evolving pathophysiology of grey matter injury may differentially influence their relationship with structural imaging markers. Therefore, further studies are warranted in OHCA survivors to investigate a relationship of early phase biomarkers with evolving brain injury after a follow-up of several years.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, although we demonstrated relationship between selected blood-based biomarker levels and grey matter volume reduction, the use of early phase brain imaging restricted our ability to assess long-term structural changes. Second, due to the quality requirements of the VBM analysis, not all patients could be included, and most of the patients with poor outcomes were excluded. This may have led to an underestimation of the correlations between the biomarker levels and grey matter volume reduction. Therefore, correlations involving GFAP and NSE cannot be ruled out. Third, the predominance of patients with favorable outcome in the current cohort may have further limited observed spatial extent of the correlations. Finally, although this study provides novel insights into the relationship between blood-based biomarkers and grey matter volume reduction, the relatively small sample size limits the power to detect subtle regional variations.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between elevated blood-based biomarkers and grey matter volume reduction within ten days following OHCA. Notably, both NfL and t-tau levels were associated with the early grey matter volume reduction, with t-tau revealing the most consistent regional correlations, spanning from the frontal cortex to the insula, and thalamus. These findings suggest that t-tau may be the most promising candidate among the four biomarkers studied for monitoring early ischemic grey matter volume reduction after OHCA. Further research is needed to evaluate the clinical utility of combining early phase MRI with blood-based NfL and t-tau measurements to identify patients at risk for subsequent neurocognitive impairment after OHCA.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Nolan, J. P. et al. European resuscitation council and European society of intensive care medicine guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med 47(4), 369–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4 (2021).

Gräsner, J. T. et al. Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Europe-Results of the EuReCa TWO Study. Resuscitation 148, 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.12.042 (2020).

Witten, L. et al. Reasons for death in patients successfully resuscitated from out-of-hospital and in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 136, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.01.031 (2019).

Stamenova, V. et al. Long-term effects of brief hypoxia due to cardiac arrest: Hippocampal reductions and memory deficits. Resuscitation 126, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.02.016 (2018).

Keijzer, H. M. et al. Brain imaging in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: Pathophysiological correlates and prognostic properties. Resuscitation 133, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.09.012 (2018).

Horstmann, A. et al. Resuscitating the heart but losing the brain: brain atrophy in the aftermath of cardiac arrest. Neurology 74(4), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cbcd6f (2010).

Byron-Alhassan, A. et al. Exploratory analyses of cerebral gray matter volumes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in good outcome survivors. Front Psychol 11, 856. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00856 (2020).

Silva, S. et al. Brain gray matter MRI morphometry for neuroprognostication after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med 45(8), e763–e771. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002379 (2017).

Carlier, J. et al. Evaluation of the cognitive outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: The role of thalamus. EJN 57(11), 1892–1912. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15978 (2023).

Hollmén, C. et al. Neuroprotective effects of inhaled xenon gas on brain structural gray matter changes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest evaluated by morphometric analysis: A substudy of the randomized xe-hypotheca trial. Neurocrit Care 42(1), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-024-02053-8 (2024).

Newcombe, V. F. J. et al. Post-acute blood biomarkers and disease progression in traumatic brain injury. Brain 145(6), 2064–2076. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac126 (2022).

Shahim, P. et al. Time course and diagnostic utility of NfL, tau, GFAP, and UCH-L1 in subacute and chronic TBI. Neurology 95(6), e623–e636. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009985 (2020).

Shahim, P. et al. Serum NfL and GFAP as biomarkers of progressive neurodegeneration in TBI. Alzheimer’s Dement 20, 4663–4676. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13898 (2024).

Shahim, P. et al. Neurofilament light as a biomarker in traumatic brain injury. Neurology 95(6), e610–e622. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009983 (2020).

Ashton, N. J. et al. A multicentre validation study of the diagnostic value of plasma neurofilament light. Nat Commun 12(1), 3400. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23620-z (2021).

Rajan, K. B. et al. Remote blood biomarkers of longitudinal cognitive outcomes in a population study. Ann Neurol 88(6), 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25874 (2020).

Stammet, P. et al. Neuron-specific enolase as a predictor of death or poor neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and targeted temperature management at 33°C and 36°C. J Am Coll Cardiol 65(19), 2104–2114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.538 (2015).

Yang, Z. & Kwang, K. K. W. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: from intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci 38(6), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.003 (2015).

Hoiland, R. L. et al. Brain hypoxia is associated with neuroglial injury in humans post cardiac-arrest. Circ Res 129(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319157 (2021).

Hol, E. M. & Pekny, M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 32, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.004 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Protective role of reactive astrocytes in brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood flow Metab. 28(3), 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600546 (2008).

Wilhelmsson, U. et al. Absence of glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin prevents hypertrophy of astrocytic processes and improves post-traumatic regeneration. J. Neurosci. 24(21), 5016–5021. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0820-04.2004 (2004).

Khalil, M. et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14(10), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0058-z (2018).

Gaetani, L. et al. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 90(8), 870–881. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106 (2019).

William, D. R. Tauopathies: classification and clinical update on neurodegenerative diseases associated with microtubule associated protein tau. J. Intern. Med. 36(10), 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01153.x (2006).

Mattsson, N. et al. Serum tau and neurological outcome in cardiac arrest. Ann. Neurol. 82(5), 665–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25067 (2017).

Moseby-Knappe, M. et al. Serum markers of brain injury can predict good neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 47(9), 984–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06481-4 (2021).

Wihersaari, L. et al. Neurofilament light as an outcome predictor after cardiac arrest: a post hoc analysis of the COMACARE trial. Intensive Care Med 47(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06218-9 (2021).

Arctaedius, I. et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein and tau: Predictors of neurological outcome after cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 28(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-024-04889-0 (2024).

Humaloja, J., Ashton, N. J. & Skrifvars, M. B. Brain injury biomarkers for predicting outcome after cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 26(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03913-5 (2022).

Ebner, F. et al. Serum GFAP and UCH-L1 for the prediction of neurological outcome in comatose cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation 154, 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.05.016 (2020).

Klitholm, M. et al. Neurofilament Light Chain and Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein as early prognostic biomarkers after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 193, 109983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109983 (2023).

Levin, H. et al. Plasma neurofilament light is a predictor of neurological outcome 12 h after cardiac arrest. Crit Care 27(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04355-3 (2023).

Hoiland, R. L. et al. Neurologic prognostication after cardiac arrest using brain biomarkers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 79(5), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.5598 (2022).

Song, H. et al. Novel serum biomarkers for predicting neurological outcomes in postcardiac arrest patients treated with targeted temperature management. Crit. Care 27(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04400-1 (2023).

Sandroni, C., D’Arrigo, S. & Nolan, J. P. Prognostication after cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 22(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2060-7 (2018).

Laitio, R. et al. Effect of Inhaled Xenon on Cerebral White Matter Damage in Comatose Survivors of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 315(11), 1120–1128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.1933 (2016).

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

Gaser, C. et al. CAT: A computational anatomy toolbox for the analysis of structural MRI data. Gigascience. 13, 049. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giae049 (2024).

Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 (2009).

Schoerkhuber, W. et al. Time course of serum neuron-specific enolase: A predictor of neurological outcome in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Stroke 30(8), 1598–1603. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.30.8.1598 (1999).

Chung-Esaki, H. M. et al. The neuron specific enolase (NSE) ratio offers benefits over absolute value thresholds in post-cardiac arrest coma prognosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 57, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2018.08.020 (2018).

Luescher, T. et al. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) improves clinical risk scores for prediction of neurological outcome and death in cardiac arrest patients: Results from a prospective trial. Resuscitation 142, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.07.003 (2019).

Randall, J. et al. Tau proteins in serum predict neurological outcome after hypoxic brain injury from cardiac arrest: Results of a pilot study. Resuscitation 84(3), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.027 (2013).

Moulaert, V., Verbunt, J. A., Van Heugten, C. M. & Wade, D. T. Cognitive impairments in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. Resuscitation 80, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.10.034 (2009).

Green, C. R., Botha, J. A. & Tiruvoipati, R. Cognitive function, quality of life and mental health in survivors of our-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. Anaesth Intensive Care 43, 568–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057x1504300504 (2015).

Raina, K. D., Callaway, C., Rittenberger, J. C. & Holm, M. B. Neurological and functional status following cardiac arrest: method and tool utility. Resuscitation 79(2), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.06.005 (2008).

Torgersen, J. et al. Cognitive dysfunction and health-related quality of life after a cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 54, 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02219.x (2010).

Ørbo, M., Vangberg, T. R., Tande, P. M., Anke, A. & Aslaksen, P. M. Memory performance, global cerebral volumes and hippocampal subfield volumes in long-term survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation 126, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.02.011 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank research nurses Keijo Leivo (Registered nurse, Turku University Hospital, was compensated for his contribution) and Tuukka Tikka (Registered nurse, Helsinki University hospital, was compensated for his contribution) for taking care of the logistics of this study.

Funding

The study was funded by Academy of Finland and by State Research Funding. HZ is a Wallenberg Scholar and a Distinguished Professor at the Swedish Research Council supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2023-00356, #2022-01018 and #2019-02397), the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101053962, and Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-71320).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

TTL had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. TTL, RP and VV: Study concept and design; VV: Image preprocessing; All authors: Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; CH, RP, VV, JP and TTL: Drafting of the first manuscript; All authors: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; TV, VV: Statistical analysis; TTL, ROR, HZ: Obtained funding; TTL: Administrative, technical, or material support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

RL is a paid governmental consultant official for the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health. HZ has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZpath, Amylyx, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, Cognito Therapeutics, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Enigma, LabCorp, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merry Life, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Quanterix, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, ScandiBio Therapeutics AB, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave, has given lectures sponsored by Alzecure, BioArctic, Biogen, Cellectricon, Fujirebio, LabCorp, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Oy Medix Biochemica AB, Roche, and WebMD, is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program, and is a shareholder of MicThera (outside submitted work). All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland and the institutional review boards of the Helsinki University Hospital and the Finnish Medicines Agency.

Consent to participate

All patients’ next of kin or legal representative gave written informed assent within 4 h after hospital arrival. Consent was sought from patients when they regained consciousness.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hollmén, C.C., Vorobyev, V., Parkkola, R. et al. Grey matter volume reduction and its association with brain-enriched blood biomarkers in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Sci Rep 15, 42219 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26322-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26322-4