Abstract

Atezolizumab has been widely used for the immunotherapy of various cancers. This study aims to analyze the adverse events (AEs) associated with Atezolizumab post-marketing using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). We conducted a retrospective analysis of the FAERS database, focusing on reports associated with atezolizumab from the first quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2024. The ADRs were stratified by demographics, event types, and reported outcomes. We performed a disproportionality analysis using the reporting odds ratio (ROR), the proportional reporting ratio (PRR), the Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN), and the empirical Bayesian geometric mean (EBGM) to assess the statistical association between atezolizumab use and specific AEs. Among the 18,310,937 non-duplicated reports collected from the FAERS database, 21,162 reports identified Atezolizumab as the “primary suspect (PS),” leading to the identification of 52,348 atezolizumab-induced AEs. The majority of AE reports (59.66%) occurred within the first 360 days of treatment, with most cases reported between 30 and 180 days of administration. A total of 494 Preferred Terms (PTs) were identified as significant across all four disproportionality-based pharmacovigilance signal assessment algorithms. The three system organ classes (SOCs) with the highest signal frequencies in AE reports were Gastrointestinal System Disorders (11.54%), Infectious and Invasive Disorders (10.12%), and Benign, Malignant, and Undetermined Tumors (including cystic and polypoid) (9.92%). The top five PTs with the strongest risk signals based on frequency screening were death, disease progression, pyrexia, anemia, and infectious pneumonia. Additionally, unexpected significant AEs were identified, including homicidal ideation, encephalitis, pancreatitis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and Guillain- Barré syndrome. Atezolizumab treatment may be associated with a range of AEs. Further studies and continued pharmacovigilance efforts are essential to better understand the long-term safety of atezolizumab and to improve patient management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atezolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI), has demonstrated clinical efficacy in several malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Hepatocellular carcinoma, triple-negative breast cancer, and urothelial carcinoma1,2,3,4,5. However, like other ICIs, atezolizumab is associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and other adverse drug reactions (ADRs), which can range from mild to life-threatening6,7. While clinical trials provide valuable insights into the safety profile of atezolizumab, their controlled environments and stringent inclusion criteria often limit the generalizability of findings to the broader, more diverse patient population encountered in real-world settings4,8.

Post-marketing pharmacovigilance is critical for identifying rare or unexpected ADRs and for assessing the drug’s safety profile across diverse populations9,10. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) serves as a vital resource for post-marketing surveillance, offering a vast repository of real-world AE reports submitted by healthcare professionals, patients, and manufacturers. Disproportionality analysis, a key method in pharmacovigilance, enables the identification of potential safety signals by comparing the frequency of specific ADRs associated with a drug to those of other drugs in the database11.

Existing literature on atezolizumab’s AEs predominantly focuses on clinical trial data or individual case reports, leaving a gap in comprehensive real-world analyses12,13. Furthermore, while some studies have utilized FAERS to explore AEs associated with ICIs, few have conducted detailed disproportionality analyses specific to atezolizumab14,15. Such analyses are essential for uncovering unexpected or rare AEs that may influence clinical decision-making and patient management strategies16.

In this study, we conducted a thorough disproportionality analysis of atezolizumab-associated AEs using the FAERS database. By leveraging this extensive dataset, we seek to identify significant safety signals and characterize the temporal patterns, system organ classes (SOCs), and preferred terms (PTs) associated with Atezolizumab’s ADRs. Additionally, we explored demographic factors, such as age and gender, that may influence the occurrence of specific AEs. Our findings will provide valuable insights into the spontaneous reporting system safety profile of Atezolizumab and contribute to the optimization of its clinical use.

This research holds significant clinical implications, particularly as ICIs continue to gain broader indications and are increasingly used in combination therapies. Identifying and understanding AEs in spontaneous reporting system settings will not only enhance patient safety but also guide healthcare professionals in anticipating and managing potential risks associated with atezolizumab. Ultimately, our study underscores the importance of integrating spontaneous reporting system evidence into the ongoing evaluation of oncology therapeutics.

Methods

Data collection and processing

We conducted a retrospective analysis using the FAERS database to assess the AEs associated with atezolizumab. The data collection period spanned from the first quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2024. The dataset was downloaded and extracted from the FAERS database and analyzed using MySQL for data processing and management. To ensure accuracy, we first removed duplicate reports and focused on AEs related to atezolizumab. A fuzzy search was conducted on the “DRUGNAME” field in the DRUG table using both the brand name “Tecentriq” and the generic name “Atezolizumab.” This allowed us to identify reports where atezolizumab was listed as the primary suspect (PS) to ensure the completeness of the data.

After filtering and de-duplicating the data, a total of 52,348 AEs reports related to atezolizumab were identified. Among these, we specifically focused on reports where atezolizumab was listed as the primary suspect drug, resulting in 21,162 reports of AEs. The data were then organized by SOCs and PTs according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®), version 24.0.

Statistical analysis

We employed four disproportionality analysis methods-Reporting Odds Ratio (ROR), Proportional Reporting Ratio (PRR), Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network (BCPNN), and Empirical Bayesian Geometric Mean (EBGM)-to investigate the relationship between atezolizumab and adverse events (AEs). The ROR method is particularly useful in minimizing bias in cases with fewer reported events17. In contrast, PRR focuses on identifying and evaluating the specific impact of various risk factors, thus enabling more effective detection of potential risks18. BCPNN excels in integrating and cross-validating data from multiple sources, efficiently managing uncertainty and missing data to improve prediction accuracy19. Meanwhile, MGPS is especially effective in detecting signals for infrequent events20,21.

This study combines ROR, PRR, BCPNN, and MGPS, leveraging the strengths of each method to broaden the scope of disproportionality-based pharmacovigilance signal assessment and validation. As a result, significant associations were identified through these four approaches. During the signal screening process, if at least one of the algorithms met the predefined criteria, the AE was considered a positive signal for the drug. Conversely, when all four algorithms satisfied the criteria, it indicated a strong association between the AE and the drug, thereby effectively reducing the risk of false-positive signals. These methods are based on 2 × 2 contingency tables, as shown in Table 1. The formulas and signal generation conditions for each method are provided in Table 2. Data processing and statistical analysis were conducted using MySQL 8.0, SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA), Excel 2021 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and R 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

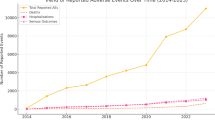

From the first quarter of 2016 to the third quarter of 2024, a total of 18,310,937 cases were recorded in the FAERS database after removing duplicate entries (6,278,302 reports). Following rigorous screening, we identified 52,348 AE reports associated with atezolizumab, among which 21,162 cases listed atezolizumab as the primary suspect drug (Fig. 1). The detailed clinical characteristics of these AE reports are shown in Fig. 2. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the number of AE reports related to atezolizumab has gradually increased over time, reaching 4,536 reports in 2023 (Fig. 2A). Notably, the number of reports in 2024 was significantly lower, as data collection was limited to the first three quarters. The countries with the highest number of AE reports were Japan (5847 reports, 27.63%), followed by the United States (4309 reports, 20.36%), India (1209 reports, 6.11%), France (1162 reports, 5.49%), China (1050 reports, 4.96%), Germany (769 reports, 3.59%), and Spain (614 reports, 2.90%) (Fig. 2B). Among all AE reports, males accounted for 53.59%, which was significantly higher than females (33.64%), with 12.72% of cases having unspecified gender (Fig. 2C). An analysis of age distribution revealed that the majority of patients (54.34%) were aged 45–75 years, while 22.24% had unspecified age (Fig. 2D). Weight analysis indicated that among patients with known weight, most weighed less than 73 kg (Fig. 2E). The primary source of AE reports was healthcare professionals, with physicians contributing 74.40% of the reports, followed by pharmacists (12.66%) and consumers (11.16%) (Fig. 2F). Additionally, we analyzed the severe outcomes associated with atezolizumab-induced AEs, including death, life-threatening events, disability, and permanent impairment/damage. Among these, hospitalization was the most frequently reported severe outcome, accounting for 42.26% of cases. Notably, these adverse events resulted in the death of 18.15% of patients, while the proportion of cases leading to disability was 1.1% (Fig. 2G).

The detailed clinical characteristics of atezolizumab associated adverse event reports. A Graph depicting the number of adverse events reported in patients treated with Atezolizumab from 2016 to 2024. B The global distribution of adverse event reports related to atezolizumab. C The proportion of adverse event reports related to atezolizumab in different genders. D The proportion of adverse event reports related to atezolizumab in different age groups. E The proportion of adverse event reports related to atezolizumab in patients with different weight. F The proportion of adverse event reports related to atezolizumab from different reporters. G The proportion of outcomes associated with atezolizumab-induced adverse events.

Signal detected at SOC level

Based on the MedDRA 24.0 version of the System Organ Class, we identified that positive signals associated with atezolizumab were distributed across 23 SOC categories. The SOCs were ranked according to the number of PT reports and the diversity of PTs within each SOC. As shown in Fig. 3A, the most common SOCs in terms of report frequency were Systemic Disorders and Various Reactions at the Medication Site, Gastrointestinal System Disorders, Various Examinations, Infectious and Invasive Disorders, Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders, and Various Neurological Disorders, each with over 3000 PT reports. In addition, four SOCs—Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders, Liver and Biliary System Disorders, Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders, and Various Injuries, Poisonings, and Complications of Procedures—exceeded 1000 reports (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, based on the ranking of SOCs by the number of PT types, the SOCs with the highest diversity of PTs associated with atezolizumab were Gastrointestinal System Disorders, Infectious and Invasive Disorders, Benign, Malignant, and Undetermined Tumors (including cystic and polypoid), Various Neurological Disorders, Various Examinations, Liver and Biliary System Disorders, and Endocrine System Disorders, each containing more than 30 distinct PT types (Fig. 3B).

The SOCs ranked by signal strength are shown in Fig. 4. Eleven SOCs were identified with a signal strength greater than 1, including Endocrine System Disorders (ROR 12.18, 95% CI 11.58–12.82), Liver and Biliary System Disorders (ROR 5.10, 95% CI 4.89–5.31), Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders (ROR 3.56, 95% CI 3.43–3.69), Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders (ROR 2.02, 95% CI 1.93–2.10), Kidney and Urinary System Disorders (ROR 2.01, 95% CI 1.83–2.01), Respiratory System, Chest, and Mediastinal Disorders (ROR 1.65, 95% CI 1.60–1.70), Infectious and Invasive Disorders (ROR 1.41, 95% CI 1.36–1.46), Benign, Malignant, and Undetermined Tumors (including cystic and polypoid) (ROR 1.38, 95% CI 1.32–1.45), Various Examinations (ROR 1.33, 95% CI 1.29–1.38), Gastrointestinal System Disorders (ROR 1.26, 95% CI 1.22–1.29), Heart Organ Disorders (ROR 1.23, 95% CI 1.17–1.29), Vascular and Lymphatic Vessel Disorders (ROR 1.23, 95% CI 1.16–1.29), and Immune System Disorders (ROR 1.01, 95% CI 1.93–1.09).

Signal detected at PTs level

Using statistical analyses based on the four algorithms-ROR, PRR, BCPNN, and MGPS-a total of 494 significant PTs comprising 21,162 reports were detected and distributed across 23 SOCs. The top 30 PTs ranked by signal strength are listed in Fig. 5. Among them, the five PTs with the highest signal strength were systemic immune activation (ROR 599.94 (317.75, 1132.74), EBGM05 = 201.64), urinary occult blood (ROR 291.13 (125.91, 673.13), EBGM05 = 98.45), polyradiculoneuropathy (ROR 319.9 (104.3, 981.15), EBGM05 = 79.83), autoimmune endocrine disorder (ROR 297.05 (97.77, 902.49), EBGM05 = 76.11), and endocrine toxicity (ROR 162.47 (83.43, 316.4), EBGM05 = 72.21). However, in terms of frequency, the top five PTs were death (n = 2186, ROR 3.11 (2.98, 3.25), EBGM05 = 2.89), disease progression (n = 1120, ROR 11.68 (11.01, 12.4), EBGM05 = 10.68), pyrexia (n = 1047, ROR 3.61 (3.39, 3.83), EBGM05 = 3.34), anaemia (n = 645, ROR 3.96 (3.66, 4.28), EBGM05 = 3.62), and pneumonia (n = 644, ROR 2.41 (2.23, 2.61), EBGM05 = 2.21). The top 30 PTs with the strongest risk signals based on frequency screening are listed in Table 3, among which 8 PTs were reported more than 500 times (Table 3). It is worth emphasizing that, unexpected significant AEs were identified, including homicidal ideation (n = 8, ROR 1.12 (1.03, 1.47), EBGM05 = 1.07), encephalitis (n = 166, ROR 30.19 (25.87, 35.24), EBGM05 = 34.18), pancreatitis (n = 131, ROR 2.91 (2.45, 3.45), EBGM05 = 3.44), disseminated intravascular coagulation (n = 71, ROR 5.75 (4.55, 7.26), EBGM05 = 7.22), Guillain- Barré syndrome (n = 60, ROR 15.36 (11.90, 19.82), EBGM05 = 19.53), and portal vein thrombosis (PVT, n = 41, ROR 15.35 (11.27, 20.90), EBGM05 = 20.60). These serious adverse events should receive close attention.

Time to event onset

We analyzed the time to onset of AEs associated with atezolizumab (Fig. 6). The analysis showed that the majority of AE reports (59.66%) occurred within the first 360 days of treatment, with 4,537 (35.23%) reports occurring between 30 and 180 days post-administration. Furthermore, only 447 reports (3.47%) occurred within the first 30 days of treatment. The proportions of AEs occurring between 180 and 360 days, 360–720 days, and > 720 days were 20.96% (n = 2699), 23.25% (n = 2994), and 17.09% (n = 2202), respectively. Additionally, 8283 AE reports did not disclose the time to event onset.

Discussion

Atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), represents a significant advancement in cancer immunotherapy. By inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, atezolizumab restores the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack tumor cells. Since its approval, atezolizumab has been utilized in treating a variety of malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma, triple-negative breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma22,23. Its integration into combination therapies, such as with Bevacizumab and chemotherapy, has further improved clinical outcomes, particularly in advanced-stage cancers3,8,24. Despite these successes, the widespread adoption of Atezolizumab underscores the need for a thorough understanding of its safety profile to optimize its use in diverse patient populations. Previous studies on AEs associated with atezolizumab have largely focused on specific AEs or have been presented in the form of case reports, failing to provide a comprehensive and systematic understanding of their characteristics and clinical outcomes6,25.

Our study, based on the FAERS database, provides a comprehensive overview of AEs associated with atezolizumab. Among the 18,310,937 reports in the FAERS database, 52,348 AEs were linked to Atezolizumab, with 21,162 cases identifying it as the primary suspect. The temporal analysis revealed that most AEs occurred within the first 360 days of treatment, peaking between 30 and 180 days post-administration. This finding aligns with the hypothesis that immune-related ADRs (irADRs) often emerge during the initial phases of treatment as the immune system reactivates. Atezolizumab, as a PD-L1 inhibitor, induces T-cell activation and immune response against tumors. The 30–180-days window aligns with the expected timeframe for irAEs, as seen with other checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab)26. In addition, survival bias must be considered, due to a significant proportion of patients progressed within the first year, potentially limiting the observable AE window for later timepoints. Patients with early progression or death (e.g., due to aggressive disease) may have discontinued treatment before later AEs could manifest, leading to underrepresentation of long-term toxicity. Observed higher proportion of atezolizumab-associated AEs in males compared to females, as identified in our study, may be attributed to several factors. Certain types of cancers for which atezolizumab is prescribed, such as lung cancer and bladder cancer, have a higher prevalence in males than females. Sex hormones, such as testosterone and estrogen, influence immune responses27. Estrogen is generally associated with enhanced immune activity, while testosterone may suppress it28. These differences could affect the immune-mediated mechanisms of atezolizumab and its associated AEs. Furthermore, an analysis of age distribution revealed that the majority of patients (54.34%) were aged 45–75 years, likely due to the higher cancer incidence and greater use of medications in this age group29. Interestingly, the regional variations in AE reporting observed here may reflect differences in healthcare systems, genetic predispositions, and reporting practices30. For instance, the higher AE reports from Japan and United States could be attributed to stringent pharmacovigilance systems and genetic factors influencing drug metabolism31.

In terms of reporting frequency, our findings aligned with expectations, confirming five significantly associated SOCs for Atezolizumab: Systemic Disorders and Various Reactions at the Medication Site, Gastrointestinal System Disorders, Infectious and Invasive Disorders, Blood and Lymphatic System Disorders, and Various Neurological Disorders. Notably, we observed that adverse events in these five SOCs were consistent with those mentioned in the drug’s prescribing information. In the context of systemic disorders and various reactions at the medication site, we observed significant AEs, including death, disease progression, and pyrexia. Death was the most common AE in this category, occurring in 18.15% of patients. In our study, infections associated with atezolizumab may be closely linked to fatal outcomes. In terms of frequency, pneumonitis ranked at the forefront. A large body of research has confirmed that pneumonitis is one of the most commonly reported fatal irAEs associated with ICIs32. Enhanced immune activity in the lungs can cause inflammation and damage, leading to respiratory failure if not promptly identified and treated33.

According to signal strength ranking, three SOCs stand out for their significant AEs: endocrine system disorders, liver and biliary system disorders, and blood and lymphatic system disorders. Endocrine disorders, particularly thyroid and adrenal diseases, are among the most commonly reported AEs following immunotherapy, and these AEs typically show reversible outcomes after Atezolizumab treatment34. Previous studies have reported incidence rates of hypothyroidism and adrenal insufficiency following anti-PD-L1 therapy ranging from 3.8–5.5% to 7.4–9.9%, respectively35,36. Additionally, type 1 diabetes is a rare but severe immune-related adverse event (irAE), which can lead to serious complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar coma in some patients37. Zhang et al. found that among 106 patients with type 1 diabetes induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors, 9 cases (8.49%) were complicated by metabolic acidosis, severe hyperglycemia, and/or acute kidney injury. This serious complication appears to be underreported in the prescribing information for Atezolizumab38.

Liver and biliary system disorders are a common category of AEs associated with Atezolizumab. In vitro studies have shown that Atezolizumab has hepatotoxicity39. Our study found that the reporting odds ratios (ROR) for immune-mediated hepatitis, liver carcinoma rupture, and portal vein embolism were 68.66, 88.98, and 164.16, respectively. These findings are consistent with reports in the literature regarding Atezolizumab-related AEs40. Additionally, cholangitis may occur concurrently with immune-mediated processes affecting abdominal organs, such as gastritis and pancreatitis41. Notably, our study identified acute severe pancreatitis as a common serious AE caused by atezolizumab (n = 131, ROR 2.91, EBGM05 = 3.44), a condition that is considered rare in the drug label42. Moreover, our results indicate that PVT is a significant AE associated with atezolizumab (ROR 15.35), whereas it is classified as a rare occurrence in the drug’s prescribing information. Setyawan et al. reported that the activation of immune cells by ICIs can result in hepatic inflammation, particularly in the portal venous system43. This inflammation may promote endothelial injury, which is a known precursor to thrombogenesis. The subsequent formation of blood clots in the portal vein can cause significant vascular obstruction, leading to clinical manifestations of PVT44. ICIs like atezolizumab can potentially alter coagulation mechanisms by influencing the balance between procoagulant and anticoagulant factors. The increased inflammatory state observed in immune-related hepatobiliary disorders may predispose patients to a hypercoagulable state, facilitating thrombus formation in the portal vein45. Beckmann demonstrated that under immunotherapy, the increased activity of vascular hemophilia factor and elevated tissue factor concentrations could provide strong evidence for atezolizumab-induced PVT46.

Various neurological disorders are noteworthy among all AEs. We found that neurological disorders associated with atezolizumab use may manifest as encephalitis, hepatic encephalopathy, cerebral infarction, myasthenia gravis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, as outlined in the prescribing information47,48,49. In contrast to the prescribing information, which classifies these as rare occurrences, Guillain-Barré syndrome was identified as a significant AE associated with atezolizumab, consistent with previous published studies50. Fan et al. performed a pharmacovigilance study based on FAERS database indicated that the onsets of Guillain-Barré syndrome were variable with a median time of 38 (range 0–628) days after ICI initiation and the outcomes tended to be severe with 61.74% hospitalization and 22.82% death51. There is currently broad consensus that if these severe neurological disorders occur, atezolizumab should be immediately discontinued and permanently discontinued.

While this study provides valuable insights into the AE profile of atezolizumab, this study does have some limitations. Firstly, since reporting to FAERS is voluntary, there may be a disproportionate number of reports from healthcare professionals or patients who have experienced severe or uncommon AEs, potentially skewing the results. Secondly, the disproportionality analysis used in this study identifies statistical associations between atezolizumab and AEs, but it does not confirm causality. The observed signals may reflect coincidental associations, particularly for rarer events or in cases where comorbidities or other drug interactions may play a role. The AEs in this study were not TRAEs and may not have been directly caused by atezolizumab treatment, only showing statistical association. Therefore, more direct research is needed to explore the relationship between them. Furthermore, the FAERS database does not consistently report detailed information on factors such as underlying health conditions, concomitant medications, or dose regimens, which may influence the occurrence or severity of AEs52. This limits the ability to perform more nuanced subgroup analyses. Lastly, this study only analyzes reported AEs and does not capture the full range of AEs that might occur but go unreported or are not deemed serious enough to warrant submission to the FAERS database. Thus, the findings may not represent the full spectrum of potential adverse events associated with atezolizumab. Thus, these findings should be interpreted with caution, and further prospective studies and clinical trials are needed.

Conclusion

This pharmacovigilance study highlights the broad spectrum of AEs associated with atezolizumab, as identified through the FAERS. Our analysis reveals that atezolizumab is linked to a wide range of AEs, with gastrointestinal disorders, infectious diseases, and malignancies among the most frequently reported system organ classes. Although the majority of AEs were observed within the first year of treatment, several serious and unexpected events, such as homicidal ideation, encephalitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, were also identified. In conclusion, while atezolizumab represents a significant advancement in cancer immunotherapy, its associated ADRs warrant careful consideration. Continued pharmacovigilance and research are essential to refine its safety profile, ensuring that patients derive maximum benefit with minimal risk.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://fis.fda.gov/extensions/FPD-QDE-FAERS/FPD-QDE-FAERS.html. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kwapisz, D. Pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 70, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02736-z (2021).

Rittmeyer, A. et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 389, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X (2017).

Felip, E. et al. Overall survival with adjuvant atezolizumab after chemotherapy in resected stage II-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower010): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. 34, 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2023.07.001 (2023).

Zhu, A. X. et al. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Med. 28, 1599–1611. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01868-2 (2022).

Roupret, M. et al. European association of urology guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: 2023 Update. Eur. Urol. 84, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.03.013 (2023).

Mascolo, A. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and cardiotoxicity: An analysis of spontaneous reports in eudravigilance. Drug Saf. 44, 957–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-021-01086-8 (2021).

Ruggiero, R. et al. Do peripheral neuropathies differ among immune checkpoint inhibitors? Reports from the European post-marketing surveillance database in the past 10 years. Front. Immunol. 14, 1134436. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1134436 (2023).

Qin, S. et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus active surveillance in patients with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave050): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 402, 1835–1847. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01796-8 (2023).

Wen, H., Lei, Y. & Mao, L. Post-marketing safety of panitumumab: A real-world pharmacovigilance study. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2024.2438749 (2024).

Baldo, P. & De Paoli, P. Pharmacovigilance in oncology: Evaluation of current practice and future perspectives. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 20, 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12184 (2014).

Arku, D., Yousef, C. & Abraham, I. Changing paradigms in detecting rare adverse drug reactions: From disproportionality analysis, old and new, to machine learning. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 21, 1235–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2022.2131770 (2022).

Ohe, Y. et al. The real-world safety of atezolizumab as second-line or later treatment in Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A post-marketing surveillance study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 52, 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyac024 (2022).

Alghamdi, E. A., Aljohani, H., Alghamdi, W. & Alharbi, F. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and potential risk of thromboembolic events: Analysis of the WHO global database of individual case safety reports. Saudi Pharm. J. 30, 1193–1199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2022.06.010 (2022).

Ruggiero, R. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and immune-related adverse drug reactions: Data from Italian pharmacovigilance database. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 830. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00830 (2020).

Seabroke, S. et al. Performance of stratified and subgrouped disproportionality analyses in spontaneous databases. Drug Saf. 39, 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0388-3 (2016).

Khouri, C. et al. Adverse drug reaction risks obtained from meta-analyses and pharmacovigilance disproportionality analyses are correlated in most cases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 134, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.01.015 (2021).

Rothman, K. J., Lanes, S. & Sacks, S. T. The reporting odds ratio and its advantages over the proportional reporting ratio. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 13, 519–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.1001 (2004).

Evans, S. J., Waller, P. C. & Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 10, 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.677 (2001).

Bate, A. et al. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54, 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002280050466 (1998).

Almenoff, J. S., LaCroix, K. K., Yuen, N. A., Fram, D. & DuMouchel, W. Comparative performance of two quantitative safety signalling methods: Implications for use in a pharmacovigilance department. Drug Saf. 29, 875–887. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200629100-00005 (2006).

Wu, J., Pan, H., Shen, L. & Zhao, M. Assessing the safety of bedaquiline: Insight from adverse event reporting system analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1382441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1382441 (2024).

Reck, M. et al. Five-year survival in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer treated with atezolizumab in the Phase III IMpower133 study and the Phase III IMbrella A extension study. Lung Cancer 196, 107924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2024.107924 (2024).

Galsky, M. D. et al. Immunomodulatory effects and improved outcomes with cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy plus atezolizumab in urothelial cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 5, 101393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101393 (2024).

West, H. et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 20, 924–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30167-6 (2019).

Cutroneo, P. et al. Psoriasis and psoriasiform reactions secondary to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Dermatol. Ther. 34, e14830. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14830 (2021).

Wang, H., Li, J., Zhu, X., Wang, R. & Wan, Y. A real-world drug safety surveillance study from the FAERS database of hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving pembrolizumab alone and plus lenvatinib. Sci. Rep. 15, 1425. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85831-4 (2025).

Dunn, S. E., Perry, W. A. & Klein, S. L. Mechanisms and consequences of sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-023-00787-w (2024).

Ozdemir, B. C. & Dotto, G. P. Sex hormones and anticancer immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 4603–4610. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0137 (2019).

Sabate Gallego, M. et al. Incidence and characteristics of adverse drug reactions in a cohort of patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in real-world practice. Front. Med. Lausanne 9, 891179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.891179 (2022).

Menang, O., Kuemmerle, A., Maigetter, K. & Burri, C. Strategies and interventions to strengthen pharmacovigilance systems in low-income and middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMJ Open 13, e071079. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-071079 (2023).

Jayaputra, K. & Ono, S. Differences between the United States and Japan in labels of oncological drugs. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 26, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4111 (2017).

Matsukane, R. et al. Continuous monitoring of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio for estimating the onset, severity, and subsequent prognosis of immune related adverse events. Sci. Rep. 11, 1324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79397-6 (2021).

Kalisz, K. R., Ramaiya, N. H., Laukamp, K. R. & Gupta, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy-related pneumonitis: Patterns and management. Radiographics 39, 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2019190036 (2019).

Song, Y. S. et al. Thyroid dysfunction after atezolizumab and bevacizumab is associated with favorable outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 13, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1159/000531182 (2024).

Ichimura, T., Ichikura, D., Hinata, M., Hida, N. & Baba, T. Thyroid dysfunction with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab after lenvatinib in hepatocellular carcinoma: A case series. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 11, 2050313X231164488. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050313X231164488 (2023).

Martella, S. et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Biological, clinical, and radiological aspects. Semin. Oncol. 50, 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2023.11.003 (2023).

de Filette, J. M. K. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case report and systematic review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 181, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-19-0291 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Combined diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state in type 1 diabetes mellitus induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Underrecognized and underreported emergency in ICIs-DM. Front. Endocrinol. Lausanne 13, 1084441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1084441 (2022).

Endo, Y., Winarski, K. L., Sajib, M. S., Ju, A. & Wu, W. J. Atezolizumab induces necroptosis and contributes to hepatotoxicity of human hepatocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411694 (2023).

Tie, Y. et al. Safety and efficacy of atezolizumab in the treatment of cancers: A systematic review and pooled-analysis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 13, 523–538. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S188893 (2019).

Jingu, D. et al. Atezolizumab-related sclerosing cholangitis with multiple liver abscesses in a patient with lung squamous cell carcinoma: A case report. Respirol. Case Rep. 12, e01324. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.1324 (2024).

Oliveira, C. et al. Immune-related serious adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 80, 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-024-03647-z (2024).

Setyawan, J., Azimi, N., Strand, V., Yarur, A. & Fridman, M. Reporting of thromboembolic events with JAK inhibitors: Analysis of the FAERS database 2010–2019. Drug Saf. 44, 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-021-01082-y (2021).

Lu, Y. & Lu, Y. Clinical predictive factors of the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors and kinase inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-024-03644-9 (2024).

Goel, A. et al. Assessing the risk of thromboembolism in cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. Eur. J. Haematol. 108, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13734 (2022).

Beckmann, M. et al. Interdependence of coagulation with immunotherapy and BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy: Results from a prospective study. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 74, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-024-03850-y (2024).

Velasco, R. et al. encephalitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review. JAMA Neurol. 78, 864–873. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0249 (2021).

Marini, A. et al. Neurologic adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review. Neurology 96, 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011795 (2021).

Pathak, R. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced myocarditis with myositis/myasthenia gravis overlap syndrome: A systematic review of cases. Oncologist 26, 1052–1061. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13931 (2021).

Jeong, Y. D. et al. Global burden of vaccine-associated Guillain-Barre syndrome over 170 countries from 1967 to 2023. Sci. Rep. 14, 24561. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74729-2 (2024).

Fan, Q., Hu, Y., Wang, X. & Zhao, B. Guillain-Barre syndrome in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Neurol. 268, 2169–2174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10404-0 (2021).

Fusaroli, M. et al. The reporting of a disproportionality analysis for drug safety signal detection using individual case safety reports in pharmacovigilance (READUS-PV): Development and statement. Drug Saf. 47, 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-024-01421-9 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the FAERS for providing the data in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (no. 2025AFB368).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gan Zhang: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; writing-original draft. Danfeng Yu: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; revised manuscript. Huan Pan: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; revised manuscript. Jiong Liu: Formal analysis; methodology; visualization; writing-original draft. Ruling Wang: Formal analysis; methodology; writing-original draft. Yunyan Wan: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology. Wuhua Zhou: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; writing-original draft; writing-review and editing; supervision. Huaxiang Wang: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; writing-original draft; writing-review and editing; supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, G., Yu, D., Pan, H. et al. Post marketing safety surveillance of atezolizumab based on a retrospective analysis of the FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS). Sci Rep 15, 42218 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26340-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26340-2