Abstract

Lightweight concrete effectively maintains structural integrity while subtly reducing the load imposed by traditional dead load limits. The current study aims to investigate the synergistic effects that can result from combining silica fume and aluminum powder in lightweight concrete. Silica fume was added to replace OPC because it has a lower density, significantly reducing the overall density of the concrete. An experimental design approach was used to examine the combined effects of aluminum powder and silica fume. In concrete, silica fume was incorporated at varying proportions to replace cement: 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. As an aerating agent, aluminum powder was added at different proportions, including 0%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5%, and 0.7%. A series of experiments was conducted to assess the fresh, mechanical, and durability characteristics of the concrete, all of which are critical for lightweight concrete. It was observed that adding aluminum powder reduces strength, while silica fume improves it. Specifically, 20% replacement of OPC with silica fume increased compressive strength, split tensile strength, flexural strength, and modulus of elasticity by 7.64%, 5.68%, 4.40%, and 3.30%, respectively. It was also found that adding aluminum powder and silica fume decreases the dry density of the concrete. Models were developed using response surface methodology, and mathematical equations were created to predict response outcomes. All responses were optimized through multi-response optimization, and experimental validation was performed to confirm the optimized results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is classified into three main categories: regular weight, heavyweight, and lightweight, depending on its level of density1. The utilization of lightweight concrete has a long history, dating back to pre-Roman times. During that period, people used porous aggregates of volcanic origin, like pumice and scoria (with densities typically ranging from 560 to 1100 kg/m3)2,3. The application of reinforced lightweight concrete (with densities around 1440 to 1840 kg/m3) in ship and barge constructions was launched in 1918, and it has become a preferred material for constructing multistory structures since the 1950s3,4. Lightweight concrete is essential as it reduces the overall structural weight, lowers foundation costs, improves seismic resistance, and enhances thermal insulation for energy-efficient buildings3.

One method for producing lightweight concrete is by replacing aggregates that are natural aggregates with either synthetic or natural lightweight aggregates5. The most naturally occurring lightweight aggregates are generally of common occurrence and are low in weight. This includes materials such as scoria, pumice, vermiculite, and clay6. For instance, by using an admixture of Scoria lightweight aggregate7 and silica fume8, it has been possible to produce lightweight concrete that can achieve a compressive strength (CS) of up to 40 MPa9. Innovative pozzolanic property-based pumice powder caters to several advantages for self-compacted concrete10. It enhances the ability to flow and reduces the tendency of segregation, while substantially boosting CS from nearly 60 MPa to 85 MPa11. However, it’s important to note that this enhancement in strength comes with a trade-off of increased stiffness12.

Indeed, researchers have explored the potential of using bio-wastes as aggregates in robust and self-compacted concrete, such as oil palm13 and walnut shells14. These bio-wastes, along with non-decomposing wastes like plastics and rubbers, are considered ideal for use as lightweight aggregates15,16. This application provides several benefits, including low thermal insulation, improved resistance to abrasion, and a solution to ongoing waste disposal issues17. Expanded polystyrene (EPS) beads also play a transformative role in the realm of lightweight aggregates by significantly reducing the weight of structures18,19. Additionally, EPS lightweight concrete, which includes fly ash, was developed by Babu et al.20.

Lightweight concrete can be produced by adding foaming agents to the mixture, resulting in the formation of numerous small voids21. Additionally, certain chemical compounds enhance the volume of concrete after it has been placed22. Aluminum (Al) powder plays a crucial role in expanding concrete and is typically produced by atomizing molten aluminum23. Since the early twentieth century24, Al powder has been widely used in concrete applications due to its reaction with the alkaline water in fresh concrete25. This reaction produces a significant volume of hydrogen gas, forming many micro-bubbles within the concrete23. During the hydration process, Al powder reacts rapidly with calcium hydroxide, releasing more hydrogen gas and creating additional micro-voids26. The use of Al powder results in a reduction of concrete’s density, which consequently decreases its durability and modulus of elasticity, making the concrete more brittle27. The reduction in concrete density due to aeration is influenced by the fineness and amount of Al powder used, as well as the water-to-cement ratio28. Despite these challenges, adding Al powder to aerated lightweight concrete offers several advantages, including enhanced noise and thermal insulation properties and improved fire resistance29,30.

Previous investigations have thoroughly explored the use of Al powder to enhance the aerated properties of concrete31. However, the addition of silica fume (SF) introduces a fresh perspective on modifying concrete32. SF is known for its pozzolanic properties, offers significant potential for partially replacing cement, thereby reducing carbon emissions and enhancing the longevity of concrete33. The combination of Al powder’s aerating effects with the pozzolanic properties of silica fume provides a unique approach to creating concrete that is both lightweight and robust, thereby improving overall performance34.

SF, with its exceptional fineness and high silica content, is recognized as an incredibly potent pozzolanic material35. The incorporation of SF into concrete can enhance various properties of the material36,37. Utilizing SF as a cement replacement material due to its lower density compared to ordinary Portland cement (OPC), which significantly contributes to reducing the overall weight of the concrete while enhancing its performance characteristics. Additionally, the use of Al powder in the production of lightweight concrete increases the concrete’s permeability due to its highly porous structure38. This combined use of silica fume, which reduces concrete density by partially replacing heavier Portland cement, and aluminum powder, which creates a porous microstructure through aeration, synergistically enhances both the structural performance and functional properties of lightweight concrete. Together, these materials contribute to creating concrete that is not only lighter but also exhibits improved mechanical characteristics and supports more sustainable construction practices. In the prior research study done by Hooton et. al.39, it was found that the amalgamation of SF led to a reduction in the porousness of concrete. Interestingly, the researchers found that the permeation characteristics of SF concretes with higher SF content could not be accurately determined. Utilization of SF in concrete not only reduces the permeability but also improves the functionality of concrete in freeze and thaw40. Some of the previous studies have indicated that concrete mixtures that incorporate SF exhibit superior resistance to freeze–thaw compared to conventional mixes of concrete40,41,42,43,44. In addition, the water-to-cement ratio of the mixtures, ranging from 0.35 to 0.45, has a positive impact on reducing surface expansion in specimens exposed to cycles of freezing and thawing41,45,46. SF in concrete enhances its CS, as a study carried out by Sahoo et al.47, found a significant increase in CS, with a maximum enhancement of 59%, when the SF content was 20%, in contrast to the control mix without SF. The advancement in CS is credited to the chemical as well as physical impacts of SF. SF improves the filling of gaps between cement particles and enhances the consolidation of solid materials, resulting in a physical effect that contributes to the increase in CS. Bhanja et. al.48 examined the mechanical characteristics of concrete with supplementary cementitious material (SCM) at different water-to-cement ratios is being studied. They found that the ideal SF content for STS falls between 15–25%.

Although several studies have separately examined the effects of Al powder and SF on lightweight concrete properties, and some research has addressed their combined use, the existing literature provides limited comprehensive analysis focused specifically on the synergistic influence of Al powder on the performance, long-term durability, and efficiency of SF-modified concrete, especially under optimized mix designs and modern experimental approaches. This study’s novelty lies in its systematic exploration and optimization of the combined effects of Al powder and silica fume on lightweight concrete, employing advanced experimental design techniques (such as response surface methodology) to develop predictive models. The research goes beyond earlier isolated or limited scope studies by rigorously quantifying their interaction effects on mechanical properties, density reduction, permeability, and durability characteristics. Furthermore, this investigation emphasizes practical mix optimization for achieving both sustainability and structural performance, filling an important knowledge gap pertinent to contemporary lightweight concrete technology. RSM models will be developed in this study to optimize the mix proportions comprised of SF and Al powder. The significance of this research is its potential to guide the development of eco-friendly, cost-effective, and durable lightweight concrete mixtures, which are increasingly demanded in sustainable construction.

Materials and methods

Materials

The concrete mix was prepared by using grade 52, type 1 ordinary Portland cement (OPC). SF was used as a cement supplementary material. SF, as a byproduct of silicon and ferrosilicon alloy production, was employed as a supplementary cementitious material containing predominantly amorphous silicon dioxide (SiO₂) with a particle size typically less than 1 µm, enhancing the concrete’s durability and strength. SF was used to replace cement partially (0–20%) due to its lower density compared to OPC, aiding in reducing concrete density for lightweight applications, while aluminum powder was added (0–0.7%) as an aerating agent to introduce air voids and further decrease density. Aluminum powder is used as an aerating agent in concrete (0%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5%, and 0.7%), having a specific gravity of about 2.68, a density of 1775 kg/m3, and a particle size distribution of about 28.66 ųm, having a grey color. The partial replacement of heavier OPC with silica fume, a lower-density pozzolanic material, contributes to reducing the cementitious matrix density. Additionally, aluminum powder acts as an aerating agent by generating microscopic gas bubbles during cement hydration, inducing controlled porosity within the concrete matrix. This porosity further decreases the dry density without significantly compromising strength. Collectively, these factors enable the concrete to meet lightweight classification despite the individual material specific gravities, as confirmed in the dry density measurements presented in this study and supported by similar findings in the literature28,49.

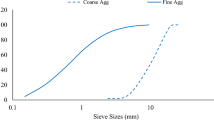

Coarse aggregate used in this investigation has the specific gravity of 2.80 and specific gravity of fine aggregate employed in this research is 2.55. The grading curves obtained by sieve analysis for coarse aggregate and fine aggregate are shown in Fig. 1. Fine aggregate used in this research passes through a #4 sieve, while the coarse aggregates are the crushed stones with a maximum size of 20 mm. ASTM C29/C29-M97 code was followed for the procedure of sieve analysis. Superplasticizer was also used in this investigation to enhance the flowability of concrete. SP (Sika® ViscoCrete®-2044) was obtained from the SIKA-KIMIA company from Malaysia. Tap water was used for the preparation of the mix proportion. The mix proportion of all the concrete mixes with varying amounts of SF and Al powder can be seen in Table 1. All the other materials, other than SF and Al powder, were kept constant. For the mix design of lightweight concrete in this study, the bulk densities of the coarse and fine aggregates were taken as 590 kg/m3 and 600 kg/m3, respectively, based on typical lightweight aggregate characteristics. These values were used to calculate aggregate quantities for the preparation of concrete mixes containing aluminum powder and silica fume. SP was maintained at 1.5% by total volume, and a constant water-to-cement ratio of 0.33 was used for all mixtures.

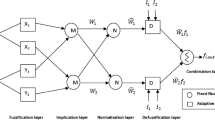

Independent and dependent factors by response surface technique

The RSM is a form of statistical analysis used to analyze the effect of numerous distinct variables on a certain dependent variable50. This kind of assessment can be conducted using a RSM. When conducting experiments with numerous independent factors, it is common practice to analyze the impact of each variable individually51. Typically, this process involves altering one variable at a time while keeping all other factors constant throughout the investigation. This commonly used method is referred to as one-variable-at-a-time, or OVAT. However, the OVAT technique has limitations, as it is unable to assess the collective influence of several individual components or their interrelationships. This method, while straightforward, does not provide insight into the complex interactions that may occur between variables52. Additionally, the augmented computing power of the Design of Experimentation (DoE) approach enables the consolidation of results from numerous analogous investigations, leading to a broad and comprehensive understanding of a specific relevant topic. This research utilized the 13th edition of Design Expert software. The selected design choice involves the use of two distinct factors: SF and Al powder, enhancing the depth and breadth of the experimental analysis. The proportions of SF range from 0 to 20% as an alternative material for cement, while the proportions of Al powder range from 0% to 0.7%. The proportions of the mixes were carefully designed, and models were generated to measure 7 important variables: CS, flexural strength (FS), STS, ultra-sonic pulse velocity (UPV), modulus of elasticity (MoE), dry density (DD), and water absorption (WA) were considered. The present investigation took an exploratory approach, conducting experiments through trial and error to examine the combined special effects of SF and Al powder on the fresh, mechanical, and reliability attributes of concrete mixes. Table 2 displays the input data for all the variables that are both dependent and independent. After developing RSM models, these models were validated by multi-objective optimization technique.

Preparation of specimen for testing

A cylindrical drum mixer was used to facilitate the mixing of concrete (presented in Fig. 2). At the first stage, all the dried material, including OPC, SF, and Al powder, along with fine and coarse aggregates, was added to the mixture and mixed properly. A super plasticizer (SP) was mixed with water, with the quantity of water kept constant for all mix designs. A mixture of water and SP was introduced after the proper mixing of the dry components. Concrete was mixed until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. After mixing samples for each specimen, were cast and molds were prepared, and oil was applied before filling the molds with concrete. Samples for CS were prepared according to ASTM C78/C79 M. Molds with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm were cast. For STS, ASTM C496 was followed, and cylindrical samples were cast; for FS, ASTM C78/ C79 M was followed, and for MoE, ASTM C469 was followed. After 24 h of sample casting, all the specimens were put in the curing tank at normal room temperature, and after 28 days of water curing, all the specimens were tested.

Results and discussion

Slump flow

Figure 3 shows the influence of SF and Al on slump flow. The influence of SF and Al powder is visible in 2D and 3D plots, as shown by the noticeable rise in slump in the red zone. From the 3D plot, it is evident that slump decreases with the addition of SF and increases with the addition of Al powder. The control mix exhibited a slump of 52.25 mm (refer to Fig. 4), with minimum slump observed at 20% SF replacement and maximum slump at 0% SF. Addition of 0.2% Al powder enhanced the slump by 4.04%, increasing to 7.07% at 0.5% Al, while replacement of OPC with SF generally reduced the slump, with the lowest slump (24.24% less than the control) at 20% SF and 0% Al.

The reduction in slump with higher SF content is attributed to its ultrafine particle size and large specific surface area, which increase the water demand of the mix by absorbing free water and filling voids between larger cement and aggregate particles, thus producing a denser and more cohesive matrix that reduces flowability53. Meanwhile, Al powder acts as an aerating agent by reacting chemically to generate hydrogen gas bubbles, which introduce microscopic air voids into the mixture, increasing the paste volume and consequently enhancing slump and flowability54. This aeration possibly reduces the internal friction between particles, allowing easier movement and better workability. Previous studies corroborate these effects: Hamada et al.36 observed decreased slump with increasing SF due to water absorption and packing effects. Concurrently, the aerating effect of Al powder has been shown to increase slump flow, consistent with the formation of hydrogen bubbles that expand the concrete volume54.

Compressive strength

Figure 5 shows the effect of SF and Al powder on CS. The highest CS occurs with 20% SF replacement and no Al powder, while the lowest strength is observed with 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder. The control mix CS was 52.25 MPa. Increasing Al powder content reduces CS, consistent with Van et al.55. Due to the creation of pores from hydrogen gas generated by the Al powder, which weakens the concrete matrix. On the other hand, SF improves CS, with up to 15% replacement showing strength gain as reported by Hamada et al.36. This enhancement from SF is primarily due to its ultrafine particles filling voids in the cement matrix (micro-filler effect) and its strong pozzolanic reaction with calcium hydroxide to form additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S–H) gel, which densifies the microstructure and strengthens the interfacial transition zone8. However, excessive SF (beyond 15–20%) may lead to strength reduction by causing an imbalance in the matrix or increasing water demand, leading to microstructural defects. Conversely, the addition of Al powder introduces microscopic air voids through chemical reaction that releases hydrogen gas, increasing porosity and thus decreasing compressive strength by reducing the effective load-bearing cross-section of the concrete56.

The graph shown in Fig. 6 demonstrates the impact of each input component on the response surface, as shown through the 2D diagrams of contour and 3D diagrams of responses. The influence of SF and Al powder is apparent, as shown by the substantial rise in CS inside the red region. The 3D graphic clearly illustrates that the inclusion of SF surges the CS, whereas the inclusion of Al powder decreases the strength. The concrete containing 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder exhibits the lowest CS, while the CS is highest when 20% of the OPC is replaced with SF and no Al powder is present.

Split tensile strength

Figure 7 shows the effects of SF and Al powder on STS. The influence of SF and Al powder is apparent, as seen by the substantial rise in STS inside the red region in 2D and 3D plots. The 3D picture unambiguously demonstrates that the addition of SF enhances the strength of the material, whereas the addition of Al powder diminishes its strength. The data indicate that the concrete with 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder exhibits the lowest STS (refer to Fig. 8). Conversely, the highest STS is seen in the concrete with 20% OPC substitution with SF and 0% Al powder. The highest STS was observed with 20% SF replacement and no Al powder, while the lowest was for 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder. The reference mix had an STS of 5.29 MPa. Increasing Al powder content consistently reduced STS, with reductions up to 29.11% at 0.7% Al powder, consistent with findings by Reddy et al.57 linked this to increased porosity from hydrogen gas generation.

The improvement in split tensile strength with SF addition can be attributed to its fine particle size, which enables it to fill voids within the cementitious matrix, refining the pore structure and enhancing particle packing. Additionally, SF participates in pozzolanic reactions that consume calcium hydroxide and generate extra C-S–H gel. This process strengthens the bond between the aggregate and cement paste, particularly in the interfacial transition zone, which contributes to improved tensile resistance. However, incorporating SF beyond an optimal content (typically above 10–15%) may lead to particle agglomeration and increased mix viscosity, reducing workability and possibly causing a decline in tensile strength. In contrast, the presence of aluminum powder adversely affects split tensile strength primarily due to the formation of hydrogen gas during its reaction in the alkaline environment of the concrete. This gas creates entrained micro air voids throughout the matrix, significantly increasing porosity and weakening the overall microstructure. The resulting higher porosity impairs the concrete’s ability to resist tensile stresses, as it facilitates crack initiation and reduces the effectiveness of stress transfer across crack surfaces. These contrasting effects clarify the observed performance trends in STS, where SF enhances tensile capacity by microstructure densification and bond improvement, while aluminum powder diminishes it by elevating porosity and compromising matrix integrity. These interpretations align well with findings reported in prior studies23,58.

Flexural strength

The graph shown in Fig. 9 demonstrates the impact of each input element on the response surface, as seen by the 2D diagrams of contours and 3D diagrams of responses. The influence of SF and Al powder is apparent, as seen by the substantial augmentation in FS inside the red region. The 3D graph unambiguously demonstrates that the incorporation of SF enhances the material’s resilience, whereas the incorporation of Al powder diminishes its strength. The research suggests that the concrete containing 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder displays the least FS. It was found that the control mix without inclusion of SF and Al powder has the FS of 4.64 MPa, when Al powder of 0.2% added to the control mix FS decreases by 12.49% while increasing the amount of Al powder to 0.5% results in a further reduction of FS by 25%. On the other hand, it was found that when 5% of OPC is substituted with SF, along with the accumulation of 0.1% of Al powder, the strength increases by 6.56%. Raising the cement substitution level to 10% with the accumulation of 0.2% Al powder results in a reduction in strength of 10.92%, while intensifying the Al content to 0.7% results in the reduction of FS by 28.44%. Moreover, increasing the level of replacement to 20% without any addition of Al powder resulted in enhancing the FS by 4.40%, while inclusion of 0.2% Al powder in the same mix diminishes the FS by 5.10%, and increasing the Al powder to 0.5% results in reducing the FS by 14.70%. Previously, an investigation was conducted on evaluating the strength of concrete by the addition of SF in concrete it was found that the addition of SF until 15% results in reducing the strength, and 20% inclusion of SF in concrete as a substitute material has the minimum strength36. It was found previously that the addition of Al powder to concrete results in the creation of pores and, as an aerating agent, it results in the production of hydrogen gas bubbles in the concrete mixture, which results in reducing the FS57.

The graph shown in Fig. 10 demonstrates the impact of each input element on the response surface, as seen by the 2D diagrams of contours and 3D diagrams of responses. The influence of SF and Al powder is apparent, as seen by the substantial augmentation in FS inside the red region. The 3D graph unambiguously demonstrates that the incorporation of SF enhances the material’s resilience, whereas the incorporation of Al powder diminishes its strength. The research suggests that the concrete containing 0% SF and 0.7% Al powder displays the least FS.

Modulus of elasticity

The graph depicted in Fig. 11 showcases the impact of each input factor on the response surface, as observed through the 2D diagrams of contours and 3D diagrams of responses. The SF and Al powder have made a noticeable impact, as shown by the considerable rise in MoE within the red area. The 3D image provides a clear illustration of how the accumulation of SF enhances the material’s elasticity, while the addition of Al powder diminishes it (refer to Fig. 11).

It was found that the control mix has the MoE of about 33.97 GPa (refer to Fig. 12), while the addition of 0.2% of Al powder in the control mix reduces the MoE by 6.02% and further increases in Al content to 0.5% reduce the MoE by 11.61%. Replacing 5% of the OPC with 0.1% Al powder mixed with 5% of SF was seen to decrease the MoE by 1.02%. Moreover, replacing the OPC with 10% of SF with 0.2% of Al powder reduces the MoE by 3.92%, while increasing the Al content to 0.5% with the same level of replacement diminishes the MoE by 9.52%, and further increasing in Al powder content to 0.7% results in reducing the MoE by 13.61%. Moreover, increasing the substitution level of OPC to 15% with 0.1% of Al content has shown a similar MoE to that of the control mix. While substituting OPC with 20% of SF increases the MoE by 3.30%, the inclusion of 0.5% Al powder to this mix proportion has shown a negative impact and reduces the MoE by 6.85%. The enhancement in MoE due to the inclusion of SF can be attributed to its ability to enhance the C-S–H formation 8, while the presence of Al powder in aerated concrete specimens possibly leads to a decrease in stiffness. This is because the Al powder causes the formation of bigger and more porous holes in the structure, resulting in lower mechanical characteristics of the concrete being tested55.

Figure 13 shows an exponential relationship between CS and MoE, described by “y = 19.517e0.0106x” with R2 = 0.9972, indicating an excellent fit. This strong correlation means MoE increases exponentially with CS, reflecting typical concrete behavior. The equation allows reliable prediction of one property from the other for the tested lightweight concrete mixes. These results aid in designing concretes with optimized strength and stiffness.

Ultrasonic pulse velocity

The graph shown in Fig. 14 illustrates the influence of each input variable on the response surface, as seen through the 2D graphical contours and 3D representation of responses. SF and Al powder have had a significant effect, evident from the substantial increase in UPV within the red area. It was found that the addition of Al powder resulted in a reduction of UPV, while SF reduces the pores, thereby enhancing the UPV.

The control mix exhibited a UPV of 3.54 km/sec (refer to Fig. 15). The addition of 0.2% Al powder to the control mix diminished the UPV by 14.85%, and further inclusion of 0.5% Al powder reduced the UPV by 28.17%. Replacing 5% of OPC with SF, along with 0.1% Al powder, reduced the UPV by 9%. When the cement substitution level increased to 10% along with 0.2% Al powder, the UPV reduced by 15.49%, whereas increasing the Al powder content to 0.5% reduced the UPV by 24.58%. Moreover, increasing the substitution level to 15% with 0.1% Al content lowered the UPV by 2.26%. Furthermore, increasing the cement replacement to 20% without any Al content in concrete increased the UPV by 7%, whereas the addition of 0.5% Al powder resulted in a decrease in UPV by 14.13%. SF is a highly reactive material with pozzolanic characteristics, consisting of very small particles with a large surface area. When incorporated into concrete, SF functions to fill the voids between cement particles and participates in chemical reactions with calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) produced during cement hydration. This reaction leads to the creation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S–H) gel59. This gel enhances the compaction of the concrete structure, leading to a decrease in the amount of empty spaces and an augmentation in the overall density of the material, which increases the UPV59. While Al powder results in introducing the pores within the concrete structure29, which results in reducing the UPV.

Dry density

The graph displayed in Fig. 16 demonstrates the impact of each input variable on the response surface, as observed through the 2D contour diagrams and 3D response plots. SF and Al powder have had a noticeable impact, as seen from the considerable rise in DD within the red area. It was found that the inclusion of Al powder led to a decrease in DD, whereas SF reduced the pores, thereby enhancing the DD.

The trial results indicate that the control mix has a DD of around 1600 kg/m3, whereas the addition of 0.2% Al powder to the control mix reduces the DD by 17.38% (refer to Fig. 17). Increasing the Al content to 0.5% in the reference mix resulted in a 17.25% reduction in DD. It was found that replacing OPC with 5% SF along with 0.1% Al powder reduces the DD by 5.56%. On the other hand, increasing the OPC replacement level to 10% with 0.2% Al powder reduces the DD by 7.62%, while increasing the Al content to 0.5% in concrete decreases the DD by 14.75%. Furthermore, 15% replacement of OPC with SF and 0.1% Al powder diminishes the DD by only 2.06%. Moreover, the concrete mix with 20% OPC replacement without any Al content enhances the DD by 9.63%, while the addition of 0.5% Al powder in the same mix proportion with 20% OPC replacement results in a 25.81% reduction in DD. The reduction in the DD with increasing SF and Al powder is likely due to SF’s lower density replacing denser cement, and Al powder generating hydrogen gas that forms microscopic air voids, increasing porosity and reducing bulk density. This combination may lead to an overall decrease in density while balancing microstructure refinement and aeration effects36,54.

Water absorption

The graph displayed in Fig. 18 demonstrates the impact of each input variable on the response surface, as observed through the 2D contour diagrams and 3D response plots. SF and Al powder have had a noticeable impact, as seen by the considerable rise in WA within the red area. The addition of Al powder was found to increase WA, while SF reduced the pores, thus decreasing WA.

Experimental results showed that the control mix has a water absorption of 5.34% (as depicted in Fig. 19), whereas the addition of 0.2% Al powder increases WA by 21.72%, and increasing the Al content to 0.5% raises WA by 89.07%. The concrete mix with 5% OPC replacement with SF and 0.1% Al powder increases WA by 16%. Increasing the OPC replacement level to 10% with 0.2% Al powder increases WA by 21.72%, while raising the Al powder content to 0.7% at the same replacement level increases WA by 61.73%. Furthermore, increasing the OPC substitution level to 15% with 0.1% Al powder resulted in an increase in WA of only 1.85%. Moreover, concrete with 20% OPC replacement without any Al powder has the lowest WA, which is 10.17% less than the control mix, whereas the addition of 0.5% Al powder to the same mix increases WA by 12.22% compared to the reference mix. Previous studies performed on the addition of Al powder in concrete found that WA in concrete increases by increasing the amount of Al powder in the concrete mix increases55. Another study that was performed previously on the influences of SF on concrete’s durability evaluation, found that accumulation of SF in concrete results in reducing the pores because of its surface area, which results in reducing the pores due to which WA also reduces and it enhances the overall durability of concrete36.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Through the model development phase, the response surface was employed to evaluate eight potential responses. The dependent variables include slump, concrete’s hardened characteristics, including CS, STS, FS, and MoE, also for analyzing durability of concrete include UPV, DD, and WA. Equation 2 represents the whole response surface. The linear model was considered the most suitable model for predicting Slump, CS, STS, and MoE. The quadratic models provided the greatest match for FS and UPV. Conversely, cubic models were considered very suitable models for DD and WA. The model employed in the application of ANOVA was confirmed using a significance level of 5% and an interval of confidence of 95%. Table 3 provides a summary of the data obtained from the analysis using ANOVA. Assuming an impact threshold of 5%, all outcomes with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered to be substantial. Based on the data presented in Table 3, Models with high F-values and likelihoods ≤ 0.05 are considered significant. The F-values demonstrated statistical significance, with the accompanying P-values for every reaction model found to be below or equivalent to 0.01. The F values of 177.19, 235.71, 85.44, 208.59, 268.53, 111.48, 4325.91, and 1015.43 for slump, CS, STS, FS, MoE, UPV, DD, & WA correspondingly may have been influenced by noise. Model terms that are noteworthy for slump, CS, STS, and MoE are A and B. For FS, noteworthy model expressions are A, B, AB, A2, and B2. Moreover, noteworthy model expressions for UPV are A, B, and A2. Furthermore, noteworthy model expressions for A, B, AB, A2, B2, A2B, AB2, A3, and B3. Noteworthy model terms for WA are A, B, AB, A2, A2B, AB2, and B3.

The following Table 4 provides a detailed summary of the validated model parameters that ought to be utilized for all of the models. The model’s forecasting precision is assessed using a statistic called the degree of determination, or R260,61. This assertion elucidates the extent to which the provided data and employed model exhibit congruity62,63. R2 may range from 0 to 100% when represented as a percentage value61,64. The regression model generated R2 values of 96.46, 97.32, 92.93, 99.05, 97.64, 98.24, 99.98, & 99.93 for the output factors slump, CS, ST, FS, MoE, UPV, DD, and WA in the present experiment. A high R2 score serves as a reliable assessment of the model’s robustness. An additional piece of evidence that showcases the exceptional workmanship invested in the product. In the ideal case, the discrepancy between the altered R2 and the anticipated R2 should not exceed a decrease of 0.2 points. The magnitude of the difference exceeds the model’s capability to explain the phenomenon under consideration. The disparity between the estimated and real values of R2 certainly does not surpass 0.2 percentage points, and this stays constant for every iteration of the model’s execution. Similarly, the ratio of signal to noise is a statistical measure that can be utilized to assess the level of tolerable meticulousness. In order to continue with this method, it is crucial to compare the diversity of anticipated values at every configuration point with the mean forecast inaccuracy. Furthermore, it is crucial to note that an accuracy level above 4 is considered suitable. The constructed model displays an extraordinary level of accuracy in providing the expected answers, consistently surpassing a precision threshold of four in all considered circumstances.

Equation 1 is derived from the given model, with the dependent variables represented by "X." Considering the input factors, the mentioned equation can predict the outcome. The model is characterized by its two input parameters, A and B. “A” indicates silica fume as a substitute for cement, while “B” represents aluminum powder used for producing lightweight aerated concrete. The parameters used in the equations above are expressed as percentages.

When assessing the accuracy of a predictive model, the main methods for diagnosis are actual vs. forecasted plots and residual plots65. The response models depicted in Figs. 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 may provide two kinds of graphs. To deem a model as a reasonable fit, it is indispensable that the data points on a plot, exemplifying the correlation among the real and anticipated values, exhibit a strong alignment with the regression line66. The data points in this particular instance of the model are aligned diagonally around the regression line, indicating a strong correlation between the projected values and the real values66. This indicator functions as a trustworthy assessment of the precision of the response models67,68,69. Furthermore, it provides a visual representation of standard lingering plots. This examination provides an indication supporting the idea that the error’s elements have a consistent distribution, as seen by the linear pattern of the dots alongside the oblique line. A key characteristic of a reliable model is its trustworthiness. This condition occurs when residuals are assumed to adhere to an average distribution. In such cases, around 95% of the residuals are predicted to fall within the range of two degrees of freedom below and above the mean, indicating a normal dispersion. All residual plots conform to this structure, proving the predictive capacity of the models. Residual and predicted plots can also be seen in Figs. 28, 29, 30, 31,32, 33, 34, 35, which shows the relationship between observed values and anticipated values. In these plots, residuals must be scattered randomly around zero, which shows the model adequately captures the variability in the data. In all these given plots, it can be seen that the models are highly adequate. Equations (2)–(9) are developed through the developed models to anticipate the outcomes.

Multi-objective optimization

Multiple-purpose optimization, also known as multi-response optimization, is a systematic approach used to determine the ideal factors that should be entered to optimize as many responses concurrently70. A considerable fraction of optimization problems faced in real-world situations require the discovery of multiple best practices while taking into account various conflicting goals. Therefore, it can be inferred that this specific approach is the most advantageous option. The model’s independent variable was optimized to improve its efficacy71. The objective function is crucial in determining the goals for every factor involved throughout the course of the optimization procedure. These aims may comprise defining the significance level. The approach to optimization entails establishing targets based on a range of parameters 16. These objectives may apply to both the sovereign and reliant factors in the model. The ultimate aim of using this strategy is to get the actual purposes while ensuring that none of the replies are modified throughout the process. The desired value, denoted by the range 0 to dj and less than 1, determines the outcome of the optimization procedure for each feasible answer72. The queried number has a range that spans from 0 to 1. The dj factor may be incremented to possibly improve the outcome, which is expressed as a percentage form. In the context of optimization with multiple goals, the geometric average has been seen to be a suitable method for assessing the attractiveness of individual solutions42. Hence, it is feasible to compute the desired value of the combination replies, as seen in Eq. (10).

The value of the variable "n" denotes the total number of replies that will ultimately be considered through the process of optimization. The word “ri” represents the degree of significance assigned to every individual function, ranging from 1 (showing low significance) to 5 (marking highest essentiality).

The current research used a similar technique, Design Expert Software, replicating the recommended process and establishing an acceptance level ranging from 0 to 1.0%. When the desirable value reaches 1%, it indicates a more favorable result for the model and strengthens the accuracy of the optimum outputs in predicting the factor that is dependent. This exemplifies the aims of factor optimization using Design Expert Software. The optimization targets for slump, CS, STS, FS, MoE, and UPV attempt to maintain the responses within the desired range. On the other hand, the primary objective of DD optimization is to maximize its response. The objective of optimization for WA is to reduce the response. The greatest values for slump, CS, STS, FS, MoE, UPV, DD, and WA are recorded as 75, 55.02, 5.44, 4.86, 34.94, 3.71, 1737.41, and 4.86, correspondingly, based on the optimization of the results. Based on the model’s variation, the overall desirability of the model is 98%, suggesting that it produces very significant results. The optimization method produced favorable results. The results of multi-response optimization may be seen in either Table 5 or Fig. 36.

Validation of models

The validation procedure was conducted to determine the extent of discrepancy between the actual response values and the predicted response values generated by the optimization technique, as shown in Table 6. The data was derived from the data shown in Table 6. To ensure utmost precision, 2 specimens for each response were tested on the 28th day of casting. The ratio of error is used to facilitate a comparison between the projected and experimentally obtained values. The percentage of error for each one of the responses is below 5%, indicating an acceptable level of reliability in the model. Put simply, the model demonstrates an exceptional degree of precision in its forecasts, serving as a witness to its dependability in scientific investigation and testing.

Conclusion

This experimental study was performed to inspect the synergistic effects of Al powder and SF to be used as a partial cement substitution material. A sequence of experiments was conducted to evaluate the flowability, CS, STS, FS, MoE, UPV, DD, and WA. Response surface models were created to analyze the reactions of various materials on lightweight concrete properties. The study is very significant as it has the capacity to radically transform the manufacturing process of lightweight concrete. Through the provision of a tailored and enhanced approach, it can efficiently harness the combined advantages of Al powder and silica fume, resulting in notable progress in the development of lightweight concrete. Several deductions were formulated based on the outcomes of this investigation:

-

(1)

The input factors for the creation of RSM models and multi-response optimisation include two inherent variables: silica fume (ranging from 0 to 20%) and Al powder (ranging from 0% to 0.7%). The dependent variables, which were expected and modified, include slump, CS, STS, FS, MoE, UPV, DD, and WA.

-

(2)

The linear model was deemed the optimal choice for forecasting Slump, CS, STS, and MoE. The quadratic models had the highest level of correspondence with FS and UPV. On the basis of the experimental data for each response variable, cubic models were deemed very appropriate for DD and WA, taking into account the level of interactions between the variables that were independent (SF = A; Al powder = B).

-

(3)

After analyzing variance (ANOVA) at a 95% assurance level with a 5% significance level, it was ascertained that each of the response models demonstrated a statistically significant level of importance, as indicated by the coefficient of determination (R2) value. This remained true, although the 5% significance threshold was significantly lower than the 95% confidence level. The R2 values, which were considered, varied between 92.93% and 99.98%.

-

(4)

Experimental findings have shown that the addition of Al powder in concrete has significantly increased the flowability of concrete, while a trend in reduction was observed by the addition of SF in concrete. Maximum slump was found at 0.5% addition of Al powder to the control mix, which is 7.07% more than the reference mixture.

-

(5)

It was found that the addition of Al powder in concrete results in reducing the concrete’s strength; conversely addition of SF in concrete enhances the strength. Maximum concrete strength was found at 20% replacement of OPC with SF, which increases CS, STS, FS, and MoE by 7.70%, 5.70%, 4.40% and 3.30% respectively.

-

(6)

To evaluate durability, UPV, DD, and WA were examined. Experiments revealed that 20% cement replacement resulted in the highest UPV, whereas the addition of Al powder decreased the UPV due to the formation of fissures. The incorporation of 0.7% Al powder with 10% OPC replacement resulted in the lowest DD, 29%, compared to the reference mixture. In contrast, WA is reduced to a minimum of 20% cement replacement due to porosity reduction.

-

(7)

The results of the comprehensive optimization analysis showed that the variables reached their optimal values in the following order: The percentage of SF is 19.76%, whereas the concentration of Al powder is 0.012%. The aforementioned settings successfully achieved the intended enhancement in characteristics while maintaining approachability. The investigational verification of the models demonstrated a mismatch of less than 5% between the actual and anticipated values of response values.

Future outlook

To guide future study, it is recommended to investigate alternative lightweight aggregates or aerating agents that may efficiently decrease the density of concrete while preserving or even improving its strength characteristics. This investigation has the potential to alleviate the adverse effects of aluminum powder on the strength of concrete. Moreover, it is crucial to do extended durability tests in order to comprehend the impact of SF and Al powder on the resilience of lightweight concrete against different environmental stressors, including freeze–thaw cycles, chemical exposure, and other environmental conditions. It is recommended to utilize some advanced statistical analysis and machine learning techniques for more accurate models and outputs. Furthermore, assessing the efficacy and appropriateness of lightweight concrete in real-world scenarios such as building construction, infrastructure projects, and precast concrete products will provide invaluable insights into its viability and applicability. Additionally, conducting a thorough life cycle evaluation of the environmental consequences of using silica fume and aluminum powder in the production of lightweight concrete would be beneficial. This evaluation should encompass factors such as energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and resource depletion, offering a comprehensive understanding of the environmental impact associated with different lightweight concrete manufacturing techniques.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, Mohammed Salem Mubarak Banaimoon, through email address [m.banaimoon@hu.edu.ye](mailto:m.banaimoon@hu.edu.ye).

References

Junaid, M. F. et al. Lightweight concrete from a perspective of sustainable reuse of waste byproducts. Constr. Build. Mater. 319, 126061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126061 (2022).

Thienel, K.-C., Haller, T. & Beuntner, N. Lightweight concrete-from basics to innovations. Mater (Basel, Switzerland). 13, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13051120 (2020).

R. P. Bohan and J. Ries. Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. 120, (Holm, 2000).

Mohammed, J. & Hamad, A. “Materials, properties and application review of lightweight concrete. Tech. Rev. Faculty Eng. Univ. Zulia. 37, 10–15 (2014).

T. W. Bremner, 8 - Lightweight concrete. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering, S. B. T.-D. in the F. and R. of C. Mindess, Ed. 167–186. (Woodhead Publishing, 2008).

Ahn, Y. B., Jang, J. G. & Lee, H. K. Mechanical properties of lightweight concrete made with coal ashes after exposure to elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 72, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.05.028 (2016).

Rajaonarison, E. F., Gacoin, A., Randrianja, R., Ranaivoniarivo, V. G. & Razafindrabe, B. H. N. Effect of scoria on various specific aspects of lightweight concrete. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 11(3), 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40069-017-0204-9 (2017).

Suryanita, R., Maizir, H., Zulapriansyah, R., Subagiono, Y. & Arshad, M. F. The effect of silica fume admixture on the compressive strength of the cellular lightweight concrete. Res. Eng. 14, 100445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100445 (2022).

Kiliç, A., Atiş, C., Yasar, E. & Özcan, F. High-strength lightweight concrete made with scoria aggregate containing mineral admixtures. Cem. Concr. Res. 33, 1595–1599. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00131-5 (2003).

Tran, Q. & Ghosh, P. Influence of pumice on mechanical properties and durability of high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 249, 118741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118741 (2020).

Revilla-Cuesta, V., Skaf, M., Santamaría, A., Hernández-Bagaces, J. J. & Ortega-López, V. Temporal flowability evolution of slag-based self-compacting concrete with recycled concrete aggregate. J. Clean. Prod. 299, 126890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126890 (2021).

Radi, K., Jauffres, D., Deville, S. & Martin, C. L. Strength and toughness trade-off optimization of nacre-like ceramic composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 183, 107699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107699 (2020).

Hamada, H. M. et al. Use of oil palm shell as an aggregate in cement concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 265, 120357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120357 (2020).

D’Eusanio, V. et al. Rosaceae nut-shells as sustainable aggregate for potential use in non-structural lightweight concrete. Waste 1(2), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1020033 (2023).

Li, X., Ling, T.-C. & Hung Mo, K. Functions and impacts of plastic/rubber wastes as eco-friendly aggregate in concrete – A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 240, 117869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117869 (2020).

Ghani, M. U. et al. Mechanical and environmental evaluation of PET plastic-graphene nano platelets concrete mixes for sustainable construction. Res. Eng. 21, 101825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101825 (2024).

Maier, D. A review of the environmental benefits of using wood waste and magnesium oxychloride cement as a composite building material. Mater (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16051944 (2023).

Abdel-Jaber, M. et al. Influence of temperature on shear behavior of lightweight reinforced concrete beams using pozzolana aggregate and expanded polystyrene beads. CivilEng 4(3), 1036–1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/civileng4030056 (2023).

Shabbar, R., Altameemi, A. & Alhassani, A. The effect of expanded polystyrene beads (EPS) on the physical and mechanical properties of aerated concrete. Open Eng. 12, 424–430. https://doi.org/10.1515/eng-2022-0020 (2022).

Babu, D. et al. “Effect of polystyrene aggregate size on strength and moisture migration characteristics of lightweight concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 28, 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.02.018 (2006).

Wang, S., Lim, J. L. G. & Tan, K. H. Performance of lightweight cementitious composite incorporating carbon nanofibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 109, 103561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103561 (2020).

Compaoré, A. et al. Preparation and characterization of foamed concrete using a foaming agent and local mineral resources from Burkina Faso. Results Mater. 17, 100365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinma.2023.100365 (2023).

Paikara, R. K. & Gyawali, T. R. Influence of aluminum powder content and powder-to-sand ratio on the physical and mechanical properties of aerated lightweight mortar. Clean. Mater. 10, 100213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2023.100213 (2023).

Kuziak, J., Zalegowski, K., Jackiewicz-Rek, W. & Stanisławek, E. Influence of the type of cement on the action of the admixture containing aluminum powder. Mater. (Basel, Switzerland). 14, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14112927 (2021).

Hamad, A. Materials, production, properties and application of aerated lightweight concrete: review. Int. J. Mater Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1270/ijmse.2.2.152-157 (2014).

Zhang, E. et al. 4 Cement”, Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering (Woodhead Publishing, 2011).

Kim, W.-K. et al. Effect of hydrogen nanobubbles on the mechanical strength and watertightness of cement mixtures. Mater (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14081823 (2021).

Hajimohammadi, A., Ngo, T. & Mendis, P. How does aluminium foaming agent impact the geopolymer formation mechanism?. Cem. Concr. Compos. 80, 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.03.022 (2017).

Kumar, M. Effect of fineness and dosage of aluminium powder on the properties of moist-cured aerated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 95, 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.122 (2015).

Ioana, A. et al. High-strength and heat-insulating cellular building concrete based on calcined gypsum. Mater (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010118 (2022).

Khunt, Y., Nathwani, V., Patel, H., Joshi, T. & Gandhi, D. Investigation on properties of autoclave aerated concrete using different pre-curing and curing techniques. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.04.047 (2023).

D. K. Panesar, “3 - Supplementary cementing materials. In: Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering, S. B. T.-D. in the F. and R. of C. (Second E. Mindess, Ed. 55–85. (Woodhead Publishing, 2019).

Khan, M. I. & Siddique, R. Utilization of silica fume in concrete: Review of durability properties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. - RESOUR Conserv Recycl 57, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2011.09.016 (2011).

Althoey, F., Ansari, W. S., Sufian, M. & Deifalla, A. F. Advancements in low-carbon concrete as a construction material for the sustainable built environment. Dev. Built Environ. 16, 100284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100284 (2023).

Al-Jumaily, I., Kareem, Q. & Hilal, N. “An overview on the influence of Pozzolanic materials on properties of concrete. Int. J. Enhanced Res. Sci. Technol. Eng.. 4, 81–92 (2015).

Hamada, H. M. et al. Effect of silica fume on the properties of sustainable cement concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 8887–8908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.147 (2023).

Shah, H. A. et al. Predicting compressive and splitting tensile strengths of silica fume concrete using M5P model tree algorithm. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15155436 (2022).

Atyia, M. M., Mahdy, M. G. & AbdElrahman, M. Production and properties of lightweight concrete incorporating recycled waste crushed clay bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 304, 124655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124655 (2021).

Hooton, R. D. Influence of silica fume replacement of cement on physical properties and resistance to sulfate attack, freezing and thawing and alkali-silica reactivity. Materials (Basel). 90(143), 151 (1993).

Oyunbileg, D., Amgalan, J., Batbaatar, T. & Temuujin, J. Evaluation of thermal and freeze-thaw resistances of the concretes with the silica fume addition at different water-cement ratio. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02633 (2023).

Karakurt, C. & Bayazıt, Y. Freeze-thaw resistance of normal and high strength concretes produced with fly ash and silica fume. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 830984. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/830984 (2015).

Khan, M. B. et al. Enhancing the mechanical and environmental performance of engineered cementitious composite with metakaolin, silica fume, and graphene nanoplatelets. Constr. Build. Mater. 404, 133187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133187 (2023).

Khan, M. B., Waqar, A., Bheel, N., Shafiq, N. & Sor, N. H. “Optimization of fresh and mechanical characteristics of carbon fiber-reinforced concrete composites using response surface technique. Buildings 13, 1–32 (2023).

Tarangini, D., Sravana, P. & Srinivasa Rao, P. Effect of nano silica on frost resistance of pervious concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 51, 2185–2189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.132 (2022).

Boddy, A. M., Hooton, R. D. & Thomas, M. D. A. The effect of the silica content of silica fume on its ability to control alkali–silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 33(8), 1263–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00058-9 (2003).

Lou, Y. et al. Performance characteristics of cementitious composites modified with silica fume: a systematic review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01753 (2023).

Sahoo, K. K., Sarkar, P. & Davis, R. Mechanical properties of silica fume concrete designed as per construction practice. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. - Constr. Mater. 172(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1680/jcoma.16.00085 (2019).

Bhanja, S. & Sengupta, B. Influence of silica fume on the tensile strength of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 35(4), 743–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.05.024 (2005).

Federowicz, K., Techman, M., Sanytsky, M. & Sikora, P. Modification of lightweight aggregate concretes with silica nanoparticles-a review. Mater (Basel, Switzerland) https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14154242 (2021).

Sarabia, L. A. & Ortiz, M. C. 1.12 Response Surface Methodology (Elsevier, UK, 2009).

Khuri, A. “A general overview of response surface methodology. Biometrics Biostat. Int. J. https://doi.org/10.1540/bbij.2017.05.00133 (2017).

Bowden, G. D., Pichler, B. J. & Maurer, A. A design of experiments (doe) approach accelerates the optimization of copper-mediated 18F-fluorination reactions of arylstannanes. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47846-6 (2019).

Lekhya, A. & Kumar, N. S. A study on the effective utilization of ultrafine fly ash and silica fume content in high-performance concrete through an experimental approach. Heliyon 10(22), e39678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39678 (2024).

Lam, T. et al. Effect of aluminium powder on light-weight aerated concrete properties. Ess Web Conf. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20199702005 (2019).

Van Tang, L. et al. Effect of aluminium powder on light-weight aerated concrete properties. E3S Web Conf. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20199702005 (2019).

Tayeh, B. A., Hakamy, A., Amin, M., Zeyad, A. M. & Agwa, I. S. Effect of air agent on mechanical properties and microstructure of lightweight geopolymer concrete under high temperature. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e00951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e00951 (2022).

Reddy, D. R. K. C. & Kumar, S. D. Effect of fly ash and aluminium powder on strength properties of concrete. JournalNX 3(07), 57–61 (2017).

Kadri, E.-H., Kenai, S., Ezziane, K., Siddique, R. & De Schutter, G. Influence of metakaolin and silica fume on the heat of hydration and compressive strength development of mortar. Appl. Clay Sci. 53(4), 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2011.06.008 (2011).

Al-Amoudi, O., Maslehuddin, M., Shameem, M. & Mohammed, I. Shrinkage of plain and silica fume cement concrete under hot weather. Cem. Concr. Compos. 29, 690–699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2007.05.006 (2007).

Kennedy, C., Bheel, N., Nadeem, G., Benjeddou, O. & Waqar, A. “Efficiency of ficus sycomorus exudates as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel pipes in acid concentrated water and soil. Safety Extreme Environ. 5, 109–118 (2023).

Waqar, A., Skrzypkowski, K., Almujibah, H., Zagórski, K. & Khan, M. B. Success of implementing cloud computing for smart development in small success of implementing cloud computing for smart development in small construction projects. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095713 (2023).

Waqar, A., Khan, M. B., Shafiq, N. & Skrzypkowski, K. “Assessment of challenges to the adoption of IOT for the safety management of small construction projects in Malaysia : structural equation modeling applied sciences. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13053340 (2023).

Waqar, A. & Almujibah, H. “Factors influencing adoption of digital twin advanced technologies for smart city development : evidence from Malaysia. Buildings https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030775 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Factors influencing adoption of digital twin advanced technologies for smart city development: evidence from Malaysia. Buildings 13(3), 775. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030775 (2023).

Li, J. Assessing the accuracy of predictive models for numerical data: Not r nor r2, why not? Then what?. PLoS ONE 12(8), e0183250. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183250 (2017).

V. Kotu and B. Deshpande, “Chapter 3 - Data Exploration,” V. Kotu and B. B. T.-D. S. (Second E. Deshpande, Eds. Morgan Kaufmann), 39–64. (2019).

Waqar, A. et al. Limitations to the BIM-based safety management practices in residential construction project. Environ. Challenges. 14, 100848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100848 (2024).

Bageis, A. S. et al. Evaluation of factors affecting the competitive advantage of organizations in establishing sustainable project management post covid-19. J. Eng. 2023, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3529313 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Analyzing the success of adopting metaverse in construction industry: structural equation modelling. J. Eng. (United Kingdom). https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/8824795 (2023).

Tahir, H., Khan, M. B., Shafiq, N., Radu, D. & Nyarko, M. H. “Optimisation of mechanical characteristics of alkali-resistant glass fibre concrete towards sustainable construction sustainability optimisation of mechanical characteristics of alkali-resistant glass fibre concrete towards sustainable construction. Sustainabitlity https://doi.org/10.3390/su151411147 (2023).

Khan, M. B. et al. “Effects of jute fiber on fresh and hardened characteristics of concrete with environmental assessment. Buildings 13, 1691 (2023).

Waqar, A. et al. Effect of volcanic pumice powder ash on the properties of cement concrete using response surface methodology. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 8, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-023-00265-7 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-33).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-33).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Muhammad Basit Khan, Mohammed Salem Mubarak Banaimoon; Methodology: Muhammad Basit Khan; Formal analysis: Badr T. Alsulami, Hamad R.Almujibah; Investigation: Madhusudhan Bangalore Ramu, Abdullah O. Baarimah; Data curation: Madhusudhan Bangalore Ramu, Madhusudhan Bangalore Ramu; Writing—Original Draft: Muhammad Basit Khan, Abdullah O. Baarimah, Writing—Review & Editing: Hamad R.Almujibah, Abdullah O. Baarimah, Ahmed Fathi Mohamed Salih Ebrahim; Supervision: Hamad R.Almujibah.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.B., Baarimah, A.O., Banaimoon, M.S.M. et al. Exploring the synergy between aluminum powder and silica fume in enhancing lightweight concrete characteristics. Sci Rep 15, 42358 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26349-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26349-7