Abstract

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is a widely practiced holistic care system in East Asia. However, concerns have arisen regarding the health risks associated with smoke inhalation from moxibustion treatments for both patients and medical staff. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare particulate matter (PM) concentrations in a TCM therapy room before and after installation of air purifiers. This study used multiple approaches to assess the impact of air filtration on PM levels and provided a more accurate evaluation. The first approach compared PM concentrations before and after implementation of air purifiers, which revealed significant reductions: PM1 decreased by 16% to 72% (p < 0.01), PM2.5 by 18% to 67% (p < 0.01), and PM10 by13% to 49% (p < 0.05) at an air turnover rate (kTO) of 5.6 h-1. The second approach compared indoor/outdoor (I/O) PM before and after implementation of air filters. The I/O ratios of PM2.5 and PM10 revealed significant reductions by 46% and 35%, respectively. The third approach used a linear regression model to evaluate the effectiveness of the air purifiers, revealing that their use significantly reduced PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations by 7.00 and 12.48 µg/m³, respectively. Despite these reductions, the percent reduction in PM2.5 was relatively low in this study, even with a moderate kTO of 5.6 h-1, comparing to other studies. This may be attributed to the high activity levels and crowded conditions in the therapy room, which limited the air purifiers’ effectiveness. Vigorous mitigation measures, such as general ventilation with infiltration device, isolated room with local exhaust ventilation, are suggested to obtain the considerable decrease in PM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has a long history and continues to be a popular holistic care system in East Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore1,2. TCM practices encompass herbal medicine, acupuncture, cupping therapy, thermal therapy, massage, and moxibustion3. Although TCM has demonstrated numerous benefits, recent safety concerns have arisen regarding moxibustion. This practice involves burning moxa, a cone or stick composed of ground mugwort leaves, on or near the meridians and acupuncture points of the body to treat a wide range of diseases4 e.g., knee osteoarthritis, diarrhea, colitis, urinary incontinence, dysmenorrhea, etc. The therapeutic effects are attributed to thermal stimulation and active compounds in moxa, such as tannins and eucalyptol, which either has radical scavenging potential or soothing effect on central nervous system4,5. However, studies have indicated that moxibustion smoke contains harmful chemicals that exceed indoor air quality (IAQ) standards and occupational exposure limits, including formaldehyde, particulate matter (PM), volatile organic compound (VOC) and CO1,6,7,8. For instance, Mo et al.7 reported a formaldehyde level of 277.8 µg/m3 (~ 0.227 ppm) in a small moxibustion room, significantly above the WHO standard of 0.08 ppm. Lu et al.6 reported that levels of PM with a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5) and PM with a diameter ≤ 10 μm (PM10) were 296 µg/m3 and 409 µg/m3 during moxibustion, which surpassed the regulatory standards of the Taiwan Indoor Air Act (35 and 75 µg/m3, respectively). These findings emphasized the importance of maintaining good IAQ in clinics when moxibustion is practiced.

The small particle size in moxa smoke can detrimentally affect human health. Decades of studies consistently show that PM generated by combustion is linked to lung inflammation and contributes significantly to the burden of cardiopulmonary diseases related to such exposures9. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) mainly from a combustion source can potentially pass through the alveoli and enter the bloodstream. Specific health effects associated with PM2.5 exposure include heart failure, stroke, hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer10,11,12,13,14. The potential impact of these health issues on the global health burden is considerable.

Studies have recommended various measures for reducing exposure to air pollutants generated by moxibustion, including source control, local exhaust ventilation, and the introduction of dilution air. For example, Hui et al.15 evaluated the source control strategy by using the moxa cylindrical device with filters. This device significantly lower PM2.5, CO and SO2 emissions compared to the control group (no cylindrical device and filter). Lu et al.6 implemented local exhaust ventilation to capture pollutants and found this strategy to be effective in reducing contaminant levels. Several studies have reported that general dilution effectively reduces air pollutant concentrations8,16,17. Where these strategies are infeasible and impractical, air purifying technologies have been developed for reducing pollutants in enclosed spaces.

An air purifier is a simple and widely available device designed to improve indoor air quality. Compared with natural / mechanical ventilation, air purifiers with particular filters are more effective at controlling indoor pollutants18. They have been used in homes occupied by seniors, patients with allergic rhinitis, and children with asthma19,20,21,22. Health benefits of air purifiers for these susceptible groups were reported, including symptom relief for allergic rhinitis patients, significant reductions in systemic inflammation, and lowered systolic blood pressure in older adults. Most studies agree that active operation of air purifiers can decrease PM2.5 concentrations. For example, a systematic literature review indicated that air purifiers reductions in PM2.5 concentrations were between 22.6 and 92.0% in comparison with control groups23.

A few studies have examined the effects of air purifier use in clinical settings. Lu et al.6 reported that an air purifier affected indoor air quality during moxibustion. Their research assessed the net impact of control measures on pollutant concentration before, during and after combustion of the moxa wool. While their study contributed valuable data, the experimental conditions did not accurately reflect typical clinical environments, where multiple treatments (e.g., acupuncture, laser acupuncture, and moxibustion) are often conducted simultaneously. Therefore, the objectives of the current study were to investigate PM concentrations in a real-world setting (a TCM clinic), and to evaluate how the use of a commercially available air purifier affects indoor air quality.

Materials and methods

Sampling location and period

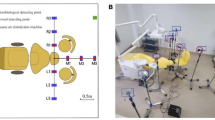

The sampling location for this study was a therapy room in the TCM department at a medical center (Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital). Figure 1 shows that the therapy room (area, 86 m2; volume,198 m3) contained 13 therapy beds and 7 therapy seats. The outpatient clinic of the department operated in 16 shifts per week (6 morning shifts, 5 afternoon shifts and 5 evening shifts).

This was a three-week design study which was conducted in October, 2022. Air purifiers were not used at the first week, and then they were activated at the second and third weeks. The sampling instrument was placed in the center of the therapy room and at least 1 m away from the purifier to obtain the average concentration in this area. The sampling height was at 1.1 m, which represented the breathing zone of a typical patient in a seated position. Measurements were taken continuously on weekdays over a 9-hour period (08:30 − 17:30) at the first week (as a baseline) and third week (one week after activation of the air purifier as an intervention). The measurements were conducted on the indoor air of the therapy room and did not involve the collection of human subject data. Therefore, informed consent was not required. Other than the use of air purifiers, all conditions remained consistent during the investigated duration of the study, including the clinic arrangement, meteorological conditions, and air conditioner use.

Sampling instrument

The Fidas frog (Palas, Germany) was used to measure indoor PM concentrations. The device can self-calibrate and operate with a volume flow rate of 1.4 L/min and measures PM sizes between 0.18 μm and 40 μm. The calibration of the system was performed regularly by using a monodisperse test powder. It enabled accurate classification of particle size distribution. The output can be expressed as particle number concentrations at different size and mass concentration of different diameters of PM1 (PM diameter ≤ 1 μm), PM2.5, and PM1024. This instrument had been evaluated by side-by-side comparison with the particulate matter measurement instrument (BAM 1020 beta attenuation mass monitor, Met One instrument, Oregon, USA) in the air quality monitoring station at AiGuo elementary school. Higher correlation was found between these two instruments with the correlation coefficients of 0.8385 and 0.7942 for PM2.5 and PM10, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Air purifier

The air purifier used in the experiment was a Honeywell InSightTM air purifier (model HPA5350WTW; dimensions 48.6 × 27.4 × 56.5 cm; 51 W, Supplementary Fig. S2). It had a three-layer filtration system. The first layer was an “active carbon pre-filter” for trapping common VOCs (toluene, acetone) and large particles. The second layer was a “powerful odor filter”. This filter, which was available for purchase separately, removed odors and VOCs that specifically originated from pets, kitchens, furniture, and cigarettes. The third layer was a “certified high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) Filter”, which filtered up to 99.97% of suspended particles as small as 0.3 μm, including specific bacteria and pollen. The air purifier had a clean air delivery rate (CADR) of 325 ft3 /min (553 m3/h), and was suitable for areas ranging from 46.3 to 92.6 m2. In an 86-m2 therapy room, two air purifiers were used, providing an estimated hourly air turnover rate (kTO) of 5.6 h-1, calculated using the CADR divided by the room volume. These two air purifiers were placed at the center of the area to obtain better efficiency as suggested by the study of Chen et al. 18. Only the first and third filter layers were installed in the air purifiers. The air purifiers were positioned near the central pilaster and beside bed No. 10 in the therapy room (Fig. 1).

Outdoor air concentrations

Outdoor air concentrations (PM2.5 and PM10) were obtained from the air quality monitoring station of the Environmental Inspection Division of the Environmental Protection Bureau of Kaohsiung City at AiGuo elementary school, which is located 0.7 km from the medical center. This station used a continuous particulate monitor BAM 1020 which was calibrated annually to obtain accurate results. The measuring data were used to investigate PM infiltration from outdoor sources to the indoor environment. Outdoor levels in October 2022 were comparable to those in other years, with correlation coefficients of 0.740–0.840 and 0.707–0.876 for PM2.5 and PM10, respectively (Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S3). These results indicate that the outdoor PM levels during the study period are representative of typical air pollution conditions.

Data analysis

Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics 22 software (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA) were used for data analysis. A t-test was used to compare PM concentrations before and after air purifier implementation. Hourly indoor/outdoor ratios were calculated, and a t-test was also applied to compare ratios before and after air purifier use. Spearmen correlation was used to assess the relationship between practices treatments in the first and third weeks. Pearson correlation was used to examine relationships among PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 concentrations, as well as indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and PM10 levels. Additionally, a general linear model was used to clarify the relationships between independent variables (intervention, outdoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, practice treatment) and dependent variables (indoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations).

Results

Practice treatment during the study period

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for various TCM treatments (Supplementary Fig. S4) during the study period. The most frequently performed TCM treatments included acupuncture, moxibustion, laser acupuncture and herbal cream with heat therapy. In the first week (before intervention), the average number (range) of procedures performed per clinic shift were as follows: acupuncture 50 (11–86), moxibustion 6 (0–16), laser acupuncture 5 (0–10), and herbal cream with heat therapy 3 (0–9). In the third week (after intervention), the respective averages for these procedures per clinic shift were 50 (13–100), 4 (0–10), 4 (0–8), and 4 (0–12). The treatment procedures in the first (baseline) and third (intervention) weeks showed a significant correlation with a range from 0.603 to 0.927 (Table 2). Since the physicians’ working shifts remained consistent across these two weeks, the patients and treatments performed on the same day of the week exhibited a degree of similarity. This indicates that the primary difference between the two weeks was the application of air purifiers.

PM concentration distribution and comparison

The mean concentration ranges (µg/m³) for PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 during the baseline week were as follows: PM1: 5.57–12.05, PM2.5: 7.02–15.41, and PM10: 23.81–54.27. During the intervention week, the concentrations were similarly ordered: PM1: 1.96–9.02, PM2.5: 2.80–10.84, and PM10: 19.38–50.54 (Supplementary Table S2). These concentrations conformed to Taiwan indoor air quality standards of PM2.5 and PM10 which are set at 35 and 75 µg/m³, respectively. The PM species distribution on a typical day indicated that PM10 concentrations substantially decreased at the noon break (Supplementary Fig. S5), which suggested that PM10 fluctuations were likely related to PM generation and resuspension from human activities25 in the clinic. Therefore, the concentration periods were divided into three time periods: morning, noon and afternoon.

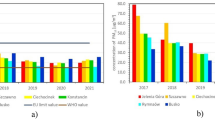

PM concentration comparisons were conducted before and after the intervention during morning and afternoon periods from Monday to Friday (Fig. 2, Table S2). The conditions during the baseline and intervention weeks were similar, including clinic arrangement, meteorological factors, and air conditioner usage, with the only difference being the use of the air purifiers. Most comparisons revealed significant differences. PM1 and PM2.5 concentrations both decreased after the intervention, with changes in PM1 ranging from − 16% to -72% (mean: -40%) and PM2.5 from − 18% to -67% (mean: -39%). Most PM10 comparisons also showed decreasing trend after the intervention, except one PM10 pair had higher concentrations after the intervention. The change in PM10 ranged from − 49% to 2% (mean: -21%). Overall, the concentration decreased significantly after the intervention for most PM pairs, except for two PM10 pairs, indicating that the air purifier was an effective measure for reducing PM levels, particularly for fine particulate matter.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients among PM1, PM2.5 and PM10, all of which were statistically significant. The correlation between PM1 and PM2.5 was very high (r = 0.985), while the correlations between PM1 and PM10 (r = 0.335) and between PM2.5 and PM10 (r = 0.455) were moderate. These differences in correlation coefficients likely arose from the different particle sizes produced by different sources; fine particulate matter primarily originates from combustion, whereas coarse PM is mainly generated from mechanical activities and biological sources26,27.

Indoor and outdoor concentration and ratio comparison

To determine whether the reduction in indoor PM levels was attributed to air purifier intervention or outdoor air influence, this study further investigated the relationship between indoor and outdoor PM levels and indoor/outdoor (I/O) ratios before and after air purifier use. During the baseline week (9 am to 5 pm), the hourly mean (range) indoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations were 10.35 (4.35–17.67) µg/m3 and 35.92 (9.63–65.93) µg/m3, respectively. Outdoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations were 28 (18–39) µg/m3 and 62 (34–84) µg/m3, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). The corresponding indoor and outdoor correlations were 0.571 (p < 0.01) and 0.014 (p = 0.929) for PM2.5 and PM10 (Table 2). During the intervention week, the hourly mean (range) indoor PM2.5 and PM10 levels were 6.70 (1.32–13.28) µg/m3 and 27.82 (4.88–93.60) µg/m3, respectively. Outdoor values were 33 (18–47) µg/m3 and 73 (46–120) µg/m3, respectively (Table S3). The corresponding indoor and outdoor correlations were 0.531 (p < 0.001) and 0.164 (p = 0.282) for PM2.5 and PM10 (Table 2). These findings indicated that indoor PM2.5 concentrations were associated with outdoor levels. The small size of outdoor fine PM allows it to easily penetrate homes and buildings easily27. In contrast, indoor PM10 concentrations were closely related to human activities in the therapy room than to outdoor levels.

Figure 3 shows the I/O ratios for PM2.5 and PM10. During the baseline week, the mean (SD) ratios were 0.37(0.11) and 0.60(0.25) for PM2.5 and PM10 respectively; in comparison, during the intervention week, the mean ratios were 0.20(0.09) and 0.39(0.20), respectively. Although outdoor levels were higher during the intervention week compared to the baseline week, the I/O ratios were significantly lower during the intervention week with reductions of 46% for PM2.5 and 35% for PM10. These findings further demonstrated the effectiveness of the air purifier in reducing PM concentrations in the TCM therapy room, especially for fine PM. This analysis provided additional evidence of air purifier intervention to lower PM levels in the TCM therapy environment.

Intervention effect

The normality test (Shapiro-Wilk test) was conducted for indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, and all p values were greater than 0.05 (Table S4), indicating the data pattern was normally distributed. Hence, a multiple linear regression model was used to investigate the effects of influential factors on indoor PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations. As shown in Table 3, implementation of air purifiers was associated with significantly lower concentrations of indoor PM2.5 and PM10, with the reduction magnitude (slope, B) of 7.00 and 12.48 µg/m3, respectively. The other significant association was the positive effect of outdoor PM2.5 concentrations on indoor PM2.5 concentrations, with a 0.30 µg/m3-increase per µg/m3 outdoor PM2.5 concentration. There were no other significant associations were found. The regression results revealed that outdoor PM2.5 concentration significantly affected indoor PM2.5, but outdoor PM10 ones did not. These results agreed with results of previous section [Indoor and outdoor concentration and ratio comparison]. As for practice treatment, no significant associations with indoor PM concentrations were found. This indicated similar work patterns of the first (baseline) and third (intervention) weeks.

Discussion

This study showed PM concentrations during both the baseline and intervention weeks met the Taiwan indoor air quality standards for PM2.5 and PM10. Additionally, the use of air purifiers significantly improved IAQ, reducing PM1, PM2.5 and PM10 by an average of 40%, 39% and 21%, respectively, at the kTO of 5.6 h− 1. The results were compared with other studies investigating PM reductions before and after air purifier interventions in various indoor environments (Table 4). For example, Cooper et al.28 examined the impact of a portable home air purifier (HAP) operating at a high kTO (16–19 h⁻¹), reporting a 45% reduction in PM2.5 after 90 min of use. Lu et al.6 reported decreases in PM2.5 and PM10 by 71% and 60% with the use of air purifier at the kTO of 2.7 h−1 during moxa wool burning in a therapy room. Another study evaluated the effects of air purifiers with windows closed in two school gymnasiums of different sizes. In the smaller gym, significant reductions were noted in particle number (93%) and PM1–10 (95%) at a kTO of 9.2 h−1, while the larger gym showed corresponding reductions of 70% and 84% at a kTO of 1.9 h−129. A separate study investigated the air purifiers’ efficacy in reducing indoor PM exposure from wood stove heating. Homes equipped with air filtration units achieved a median PM2.5 reduction of 62% compared to pre-intervention levels, at kTO rates ranging from 1.9 to 4.0 h−130. Zhang et al.31 reported mean PM2.5 reduction rates of 63% and 46% in three nurseries with windows closed and open, respectively, at a kTO of 3.1–4.8 h−1.

Several other studies have compared PM concentrations between air purifiers equipped with true filters and those with sham filters. Brehmer et al.32 reported that true filters achieved a mean reduction of 56% in PM2.5 concentrations in bedrooms of children with asthma at an average kTO of 4.4 h−1, compared to sham filters. A similar study observed a median reduction of 59% in PM2.5 at a turnover rate of 6–39 h−133. Studies conducted in college dormitories also highlighted the differences in PM2.5 between true and sham modes. For instance, Cui et al.34 found that true mode achieved a 72.4% reduction at a kTO of 3 h−1, and Li et al.35 reported a mean reduction of 82% at a kTO of 3.3 h−1. Huang et al.36 evaluated the “auto-mode” feature of a portable air purifier, which automatically activated in response to PM2.5 concentrations, across six households. The PM2.5 and PM2.5 I/O ratios were significantly lower in auto mode at the kTO range of 0.5–1.1 h−1 in comparison with sham mode, with average reduction of 40% and 45%, respectively. In addition, a study comparing the effectiveness of commercially available high-efficiency (HE) and low-efficiency (LE) air filters and found that HE filters reduced indoor PM2.5 levels by 60%, while LE filters achieved a 52% reduction, at the kTO of 2.3 h−1, relative to no filtration37.

The overall consensus supports that air purifiers are effective in reducing indoor PM concentrations. However, the percent reduction in PM2.5 observed in this study (39%) was relatively low, even with a moderate kTO of 5.6 h-1, compared to other studies which reported reduction in PM concentration around 40% or higher (Fig. 4). Possible explanations included increased activity levels (e.g., practice treatments) and a higher number of occupants in the therapy room compared to other indoor environments. Therefore, the occupancy data from this study and previous studies are summarized in Table 4. These factors likely contributed to substantial pollutant emissions, limiting the air purifier’s efficiency in the therapy room. To achieve a more significant reduction in PM levels, more vigorous or combined measures may be necessary. Potential measures or strategies include using independent air-conditioning systems with outdoor air infiltration devices1, designating isolated rooms with local exhaust ventilation exclusively for moxibustion therapy6, scheduling frequent vacuum cleaning, conducting routine maintenance to ensure optimal device performance38, and utilizing a combination of mitigation controls39,40 (such as air purifier, air-conditioner, general ventilation with infiltration). Additionally, high level of outdoor ambient PM is a potential confounding factor for the indoor environment. This phenomenon was demonstrated by Pacitto et al.29 and Zhang et al.31 which reported that open windows compromised the effectiveness of an air purifiers in reducing submicron particle concentrations.

The CADR rating evaluates an air purifier’s efficiency in removing particles of three size ranges (5–11 μm, 0.5–3 μm, and 0.09–1 μm) to achieve “clean air.“. As such, it is used as a criterion for selection of air purifiers41. To account for room size, a CADR-related indicator, kTO (\(\:=\frac{CADR}{Room\:size}\)), was developed to evaluate the performance of the air purifier in this study. This indicator represents the number of times that total clean air is supplied to the room by air purifiers in an hour. Our results showed no relationship between kTO and the percent reduction in PM2.5 (Fig. 4). This suggested that other factors beyond the air purifier’s removal efficiency, such as pollutant generation rates and the number of pollutant sources, are important factors for indoor PM concentration. This was evident in our findings that lower reduction percentages (21–40%) in PM concentrations at modest rate of kTO (5.7 h-1) were attributed to frequent practice activities and a high number of occupants (~75 persons, Table 4) in the therapy room which compromises the performance of the air purifiers. Figure 4 also shows that a kTO value higher than 10 resulted in only a moderate reduction of PM2.5 reduction. Incomplete mixing42 or short circuit may occur at such high turnover rate, leading to underperformance of the air purifier. Moreover, a higher turnover rate may increase energy consumption. This indicated that the source intensity should be considered for selection of air purifiers, not merely based on room area. Additionally, a kTO value in the range of 1–10 can be designed to achieve better air purifier performance and energy efficiency.

This study was conducted in Oct. 2022, during which both baseline and intervention measurements were obtained within a short period. To evaluate whether this month was representative of typical TCM therapy conditions, the average number of patients per day in different months was examined. The average daily patient number in October was 106, which was close to annual average of 108 patients (Supplementary information Fig. S6). The lowest and highest patient numbers occurred in May (95 patients) and December (118 patients), respectively. Considering the number of patients as a surrogate indicator of source strength, the variation in outcomes was within the range of 10.4% (106 − 95)/106 to 11.3% (118 − 106)/106. These variations are acceptable, indicating the use of air purifier remains an effective intervention after adjusting for this variability.

Several limitations of this study are acknowledged. First, PM concentrations were measured at a single sampling site, and its representativeness for other locations within the room is uncertain. Nevertheless, the TCM therapy room used in the experiments in this study was a spacious, open area without partitions, frequent movement of medical staff and patients provided a well-mixing condition in the therapy room, and the sampling instrument was positioned in the center of the room. As such, air samples included air in and near the neighboring area, and could possibly provide an estimation of mean concentration in the therapy room. Additionally, PM was compared before and after usage of air purifiers on the same day of the week, and patients were randomly arranged on the therapy bed or seat. Therefore, use of a single sampling site likely had a small effect on the comparison results. A second limitation is that the air purifier used in the experiment was not equipped with a second layer of filters designed to remove specific pollutants, such as formaldehyde, which is emitted during moxibustion. As a result, the air purifier was not operating at maximum efficiency. Still, significant decreases in PM concentrations (21–40%) were observed during the intervention week. The third limitation is that particle measurements were limited to the size range of 0.18–0.4 μm, which may underestimate or overlook particles smaller than 0.18 μm. Fortunately, Yu et al.43 demonstrated that the particle size of moxibustion fume ranges from 0.25 to 2.5 μm, with a number median diameter of 0.3 μm. This size distribution falls within the measurement range used in the present study.

This study also has several strengths. First, it is the first one to investigate air purifier effectiveness in an actual TCM practice environment, providing valuable knowledges into their application in real-world settings. Second, multiple approaches were used to evaluate the impact of air purifier usage on PM concentrations. In addition to comparing absolute PM concentrations before and after the intervention, this study also analyzed I/O ratios (relative scale), and applied a linear regression model to evaluate the effects of air purifier’s effectiveness. The multiple approaches confirmed the reduction in PM concentrations, and enabled to evaluate the magnitude of reduction in terms of absolute (-7 µg/m3 in PM2.5, -12.48 µg/m3 in PM10) and relative (-39% in PM2.5, -21% in PM10) scales. Third, the study revealed the turnover rate (kTO) of the air purifier, which provides an index of an air purifier performance evaluation in a certain indoor space. Overall, this study demonstrated that application of air purifier is an effective intervention for improving indoor air quality.

Conclusions

This study used multiple approaches to evaluate the effectiveness of an air purifier in mitigating PM concentrations, including comparisons of absolute concentrations and relative scales (I/O ratios), and the application of a linear regression model. During the baseline week, the mean concentration ranges of PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 were 5.57–12.05, 7.02–15.41 and 23.81–54.27 µg/m3, respectively. These values decreased during the intervention week to 1.96–9.02, 2.80–10.84 and 19.38–50.54 µg/m3, respectively. As a result, the average reduction percentages were 40% for PM1, 39% for PM2.5, and 21% for PM10. Similarly, I/O ratio comparisons showed significant reductions for PM2.5 and PM10, with average decreases of 46% and 35%, respectively. Regression analysis further supported the findings, showing significant concentration reduction in PM2.5 (7.00 µg/m3) and PM10 (12.48 µg/m3) after the air purifier usage. Despite the different origins of fine and course PM (fine PM being more influenced by outdoor levels, while course PM by indoor activities), these approaches consistently demonstrated that the air purifier effectively reduced indoor PM across all size classes in the TCM department. The percent reduction in PM2.5 was relatively low in this study, even with a moderate kTO of 5.6 h− 1, compared to other studies. Therefore, more vigorous mitigation measures are suggested. This multiple-faceted evaluation method provides a comprehensive and accurate assessment of air purifier performance and it is advisable to be used for assessment of control measures or interventions aimed at mitigating indoor air pollution.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hsu, Y. C., Chao, H. R. & Shih, S. I. Human exposure to airborne aldehydes in Chinese medicine clinics during moxibustion therapy and its impact on risks to health. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. A-Toxic/Hazardous Substanc. 50, 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2015.981112 (2015).

Matsumoto, T., Katai, S. & Namiki, T. Safety of smoke generated by Japanese Moxa upon combustion. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 8, 414–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2016.03.005 (2016).

Tang, J. L., Liu, B. Y. & Ma, K. W. Traditional Chinese medicine. Lancet 372, 1938–1940. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61354-9 (2008).

Deng, H. & Shen, X. The mechanism of moxibustion: ancient theory and modern research. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013 (379291). https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/379291 (2013).

Yang, J. et al. Effect of Moxa smoke produced during combustion of Aiye (Folium artemisiae Argyi) on behavioral changes in mice inhaling the smoke. J. Tradit Chin. Med. 36, 805–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0254-6272(17)30019-5 (2016).

Lu, C. Y., Kang, S. Y., Liu, S. H., Mai, C. W. & Tseng, C. H. Controlling indoor air pollution from moxibustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060612 (2016).

Mo, F. et al. Characteristics of selected indoor air pollutants from moxibustion. J. Hazard. Mater. 270, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.01.042 (2014).

Wheeler, J., Coppock, B. & Chen, C. Does the burning of Moxa (Artemisia vulgaris) in traditional Chinese medicine constitute a health hazard? Acupunct. Med. 27, 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/aim.2009.000422 (2009).

Wu, W., Jin, Y. & Carlsten, C. Inflammatory health effects of indoor and outdoor particulate matter. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.981 (2018).

Brook, R. D. et al. rd,. . Metabolism. particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121, 2331–2378. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1 (2010).

Fuks, K. et al. Heinz Nixdorf recall study Investigative, G. Long-term urban particulate air pollution, traffic noise, and arterial blood pressure. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 1706–1711. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1103564 (2011).

Lim, S. S. et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 380, 2224–2260. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8 (2012).

Raaschou-Nielsen, O. et al. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: prospective analyses from the European study of cohorts for air pollution effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol. 14, 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70279-1 (2013).

Wright, R. J. & Brunst, K. J. Programming of respiratory health in childhood: influence of outdoor air pollution. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 25, 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835e78cc (2013).

Hui, X. et al. Emission of fine particulate matter, CO, SO2, and NO2 during Moxa’s coumbustion in different Moxa device. Jouranl Beijing Univ. Traditional Chin. Med. 2, 160–164 (2018).

Huang, J. et al. Emission characteristics and concentrations of gaseous pollutants in environmental Moxa smoke. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 16, 398–404. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2015.01.0027 (2016).

Kwon, O. S. et al. Safety recommendations for Moxa use based on the concentration of noxious substances produced during commercial indirect moxibustion. Acupunct. Med. 35, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2016-011105 (2017).

Chen, K. Y., Tan, Z. N., Zhou, H. D. & Tan, Y. Optimization of operations of air purifiers for control of indoor PM2.5 using BIM and CFD. Buildings 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010077 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Efficacy of indoor air purification in the treatment of Artemisia pollen-allergic rhinitis: A randomised, double-blind, clinical controlled trial. Clin. Otolaryngol. 45, 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13514 (2020).

Park, H. K., Cheng, K. C., Tetteh, A. O., Hildemann, L. M. & Nadeau, K. C. Effectiveness of air purifier on health outcomes and indoor particles in homes of children with allergic diseases in Fresno, california: A pilot study. J. Asthma. 54, 341–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2016.1218011 (2017).

Morishita, M. et al. Effect of portable air filtration systems on personal exposure to fine particulate matter and blood pressure among residents in a Low-Income senior facility: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 1350–1357. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3308 (2018).

Shao, D. et al. Cardiorespiratory responses of air filtration: A randomized crossover intervention trial in seniors living in beijing: Beijing indoor air purifier StudY, BIAPSY. Sci. Total Environ. 603–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.095 (2017).

Cheek, E., Guercio, V., Shrubsole, C. & Dimitroulopoulou, S. Portable air purification: review of impacts on indoor air quality and health. Sci. Total Environ. 766, 142585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142585 (2021).

Palas GmbH. Fidas® Frog System. https://www.palas.de/en/product/fidasfrog (2022).

Park, S. et al. Development of air purifier operation guidelines using grey box models for the concentrations of particulate matter in elementary school classrooms. Aerosol Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/02786826.2023.2187691 (2023).

Masri, S., Kang, C. M. & Koutrakis, P. Composition and sources of fine and coarse particles collected during 2002–2010 in Boston, MA. J. Air Waste Manag Assoc. 65, 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2014.982307 (2015).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. What is Particle Pollution? https://www.epa.gov/pmcourse/what-particle-pollution#where (2021).

Cooper, E., Wang, Y., Stamp, S., Burman, E. & Mumovic, D. Use of portable air purifiers in homes: operating behaviour, effect on indoor PM2.5 and perceived indoor air quality. Build. Environ. 191 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107621 (2021).

Pacitto, A. et al. Effect of ventilation strategies and air purifiers on the children’s exposure to airborne particles and gaseous pollutants in school gyms. Sci. Total Environ. 712, 135673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135673 (2020).

Ward, T. J., Semmens, E. O., Weiler, E., Harrar, S. & Noonan, C. W. Efficacy of interventions targeting household air pollution from residential wood stoves. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 27, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2015.73 (2017).

Zhang, S., Stamp, S., Cooper, E., Curran, K. & Mumovic, D. Evaluating the impact of air purifiers and window operation upon indoor air quality - UK nurseries during Covid-19. Build. Environ. 243 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110636 (2023).

Brehmer, C. et al. The impact of household air cleaners on the chemical composition and children’s exposure to PM2.5 metal sources in suburban Shanghai. Environ. Pollut. 253, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.003 (2019).

Cox, J. et al. Effectiveness of a portable air cleaner in removing aerosol particles in homes close to highways. Indoor Air. 28, 818–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12502 (2018).

Cui, X. et al. Cardiopulmonary effects of overnight indoor air filtration in healthy non-smoking adults: A double-blind randomized crossover study. Environ. Int. 114, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.010 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: A Randomized, Double-Blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation 136, 618–627. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796 (2017).

Huang, C. H. et al. Impacts of using auto-mode portable air cleaner on indoor PM2.5 levels: an intervention study. Build. Environ. 188 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107444 (2021).

Maestas, M. M. et al. Reduction of personal PM2.5 exposure via indoor air filtration systems in detroit: an intervention study. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 29, 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-018-0085-2 (2019).

Yu, Z. H., Fan, B. J., Shen, R. Q., Zhou, X. T. & Liu, J. X. Exploring the filtration performance and usage cost of commercial fiber air filters for capturing Moxa smoke aerosols. Sep. Purif. Technol. 348 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127685 (2024).

Jia, L. Z. et al. Synergistic impact on indoor air quality: the combined use of air conditioners, air purifiers, and fresh air systems. Buildings 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061562 (2024).

Lee, D. et al. Strategies for effective management of indoor air quality in a kindergarten: CO2 and fine particulate matter concentrations. Toxics 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11110931 (2023).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (ed Indoor Environments Division). Washington, D.C., (2018).

Du, L., Batterman, S., Godwin, C., Rowe, Z. & Chin, J. Y. Air exchange rates and migration of VOCs in basements and residences. Indoor Air. 25, 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12178 (2015).

Yu, Z. et al. An efficient thumbtack-cylinder type wet electrostatic precipitator for Moxa smoke aerosol control. Powder Technol. 424, 118562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2023.118562 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank several undergraduate students, including Yi-Te Liu, Yu-Yang Tsai, Chia-Ling Yeh, Yun-Ting Ying, He-Fan Zhang, Yu-Hsuan Tseng, Yen-Chun Lee and Yu-Hsiang Chang for data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.P.; methodology: H.L., T.L., and C.P.; validation: H.L., T.L., J.C.; formal analysis: Y.H., L.Y.; data curation: Y.H., H.L., C.P.; writing-original draft preparation: Y.H.; writing-review and editing: C.P.; supervision: C.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YF., Lan, CH., Lin, TS. et al. Evaluating the impact of air purifier intervention on particulate matter concentrations in a traditional Chinese medicine therapy room using multiple approaches. Sci Rep 15, 42239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26355-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26355-9