Abstract

The longitudinal course of epilepsy remains largely unpredictable. This study aimed to predict final outcome and classify dynamic longitudinal trajectories using artificial intelligence. A total of 2586 patients who first visited our epilepsy specialists between 2008 and 2017 and with at least 3 years of follow-up, were retrospectively enrolled. Supervised and unsupervised learning algorithms were employed to identify clusters with distinct longitudinal courses and to examine epilepsy parameters within each cluster. XGBoost showed slightly higher performance than the others for the final outcome prediction. We identified three clusters associated with final seizure freedom and two clusters with persistent seizures. The first cluster demonstrated early remission, often linked to infectious or immune etiologies. Two additional clusters with final seizure freedom exhibited delayed remission. One of these clusters, characterized by relatively lower initial seizure frequency, showed generalized irregular slowing on EEG, and cerebromalacia. The other cluster, with an intermediate seizure frequency, displayed features commonly associated with generalized epilepsy. The fourth cluster displayed ongoing seizures with reduced frequency compared to baseline, with focal spike-and-wave, irregular slowing on EEG, and epilepsy-associated tumor. The fifth cluster experienced consistently high seizure frequency from onset, characterized by hippocampal sclerosis, male predominance, and longer epilepsy duration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a significant disease that causes long-term disability from personal and social perspectives due to unexpected seizures and comorbidities. Conventionally, epilepsy patients have been classified based on epilepsy or seizure types, since it is phenotypically intuitive and easily applicable in clinical settings based on EEG, and also could have provided guidance in the selection of antiseizure medications (ASMs). However, whether epilepsy patients become drug-resistant or experience seizure remission is not solely dependent on the seizure or epilepsy types. For instance, the rates of drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) also differ significantly between the major epilepsy pathologies, such as hippocampal sclerosis (HS) (Cheval et al. 20231) with 75% DRE and focal cortical dysplasia (FCD)2 with 94% DRE. Moreover, epilepsy exhibits considerable heterogeneity, including variations in clinical factors, laboratory findings, and genetic landscape beyond etiology and seizure types. Early prediction of refractory cases based on the factors of epilepsy enables shortening unnecessary medical treatment, which might reduce the delay to surgical options. Numerous previous research has addressed the predictable factors of DRE and a recent meta-analysis summarized the predictors of DRE including clinical factors, epilepsy factors, and ASM factors3.

Given the high variability in the clinical course of epilepsy4, focusing solely on epilepsy type or etiology is insufficient to fully explain or predict patients’ dynamic trajectories. Even among patients with similar final outcomes, individual longitudinal outcomes can vary significantly, highlighting the need for research that extends beyond traditional final outcome predictions. Classifying patient subtypes with varied courses based on multiple clinical parameters is fundamental to delivering optimal care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising new paradigm emerging in the healthcare field, with machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) as its primary subdivisions. In the epilepsy field, numerous types of AI research using EEG signals5,6 and images7,8,9,10,11 with or without clinical variables have been conducted to predict impending seizures and epilepsy outcomes. However, the novel classification of epilepsy patients with AI in long-term large-population cohort data has been seldom studied.

In this context, this study aimed to classify epilepsy patients by integrating comprehensive longitudinal seizure trajectories through AI methodologies, utilizing initial clinical factors, imaging, and laboratory data. Leveraging AI to analyze dynamic seizure outcomes provides a more detailed understanding of patient subgroups and supports their early identification.

Results

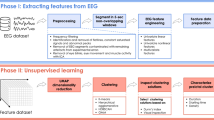

This cohort comprised the total population who visited our epilepsy center for the first time over 10 years, from 2008 to 2017. The study design is shown in Fig. 1A.

A total of 2586 patients (female, 46.1%) were analyzed. Among them, ‘de novo’ cases were individuals who had no history of epilepsy treatment or were managed less than 3 months from our clinic visit if any. The proportions of de novo and referred cases were 1368 (52.9%) and 825 (31.9%), respectively. For 401 patients (15.5%), the treatment records from other hospitals were not accurately recorded, making it impossible to distinguish whether they were de novo or referred cases. The onset age of epilepsy was 29.6 ± 19.6, and the age of the first visit to our center was 36.0 ± 17.4. The median duration of epilepsy was 2 years (interquartile range 2–10). The number of patients with focal epilepsy, generalized epilepsy, combined, and unknown were 1924 (74.4%), 467 (18.1%), 154 (6.0%), and 41 (1.6%), respectively. Regarding etiology, structural (873, 33.8%) was the most common, followed by genetic (438, 16.9%), immune (90, 3.5%), infectious (53, 2.0%), hypoxic (5, 0.2%), and metabolic (3, 0.1%), in order of frequency. However, 1124 patients (43.5%) had an unknown etiology (Table 1).

Prediction of the final outcome

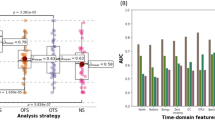

The mean followed-up duration for the cohort was 7.65 ± 2.75 years. The number of seizures before entering the cohort was 22.5 ± 97.2 per year, and in the last year, it was 6.5 ± 56.2, which was significantly improved (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). SF for more than 1 year at the final follow-up was found in 1709 patients (66.1%).

For the final outcome prediction analysis, we analyzed the status just before surgical intervention in patients who underwent surgery. The training, validation, and test sets of the SF versus NSF groups consisted of 1017 versus 520, 340 versus 173, and 340 versus 173 patients, respectively. Among tree-based algorithms, XGB showed slightly higher performance than the others. The ACC, AUC, F1 score, TPR, TNR, PPV, and NPV were 0.756, 0.727, 0.560, 0.514, 0.835, 0.614 and 0.772, respectively. The AUCs of RF, LGB, CATB, and SAINT were 0.750, 0.749, 0.711, and 0.733 respectively (Table 2). SHAP analysis demonstrated that age of onset, duration of epilepsy, and some blood parameters such as fibrinogen and absolute neutrophil count, are explainable factors of final outcome prediction performance (Fig. 2A, B).

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and clusters analysis related to final outcome. (a) The importance of each variable and (b) SHAP value predicting the final outcome based on initial clinical and laboratory information. The parameters how explained for the outcome prediction in an order of power. Feature values show older age onset (indicated by red color) and shorter duration of epilepsy (indicated by blue color) is more likely to predict final seizure freedom.

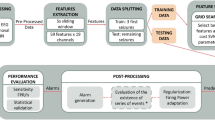

Prediction of the longitudinal outcome

Unsupervised learning revealed five clusters through the optimization of hyperparameters, based on initial epilepsy data (Fig. 3A). Among those, cluster 1, 2 and 3 were associated with good outcome, and cluster 4 and 5 were associated with poor outcome. NSF ratios in the entire cohort were 0.274, 0.088, and 0.215 for cluster 1, 2 and 3. Those of cluster 4, and 5 were 0.714, and 0.787 respectively. In more detail, cluster 1 is characterized by intermediate frequency and late remission, where seizures improve later but eventually lead to sustained seizure freedom (“intermediate-frequency and late remission”). Cluster 2 is defined by early seizure remission, with seizures improving early and leading to sustained seizure freedom (“early remission”). Cluster 3 exhibited a lower seizure burden with late remission (“lower-frequency and late remission”). Cluster 4 demonstrated a persistent seizure pattern with a reduction in seizure frequency compared to the initial stage (“decreasing-frequency and persistent”). Finally, cluster 5 exhibited continued seizures at a high frequency, similar to the initial stage (“high-frequency and persistent”) (Fig. 3B). The significant clinical characteristics obtained by multiple logistic regression of each cluster are shown in Fig. 4B. Among the seizure-free clusters, cluster 1 was characterized by generalized spike-and-wave patterns on EEG and a genetic etiology, indicating typical generalized epilepsy category. Cluster 2 was associated with infectious or immune etiologies and the presence of co-medications. Cluster 3 exhibited generalized intermittent slowing on EEG, cerebromalacia, and regional atrophy and vasculitis or demyelinating disease on MRI. Cluster 4, from the non-seizure-free clusters, was associated with focal spike-and-wave patterns and slowing on EEG, as well as the presence of a tumor on MRI. Lastly, cluster 5 was characterized by HS, migration disorder other than FCD, male, longer duration of epilepsy, and referred cases (Fig. 4A). The pairwise comparisons of significant characteristics are shown in Fig. 4B and Table 3.

Clusters from unsupervised learning. (A) Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications clustering with Noise (HDBSCAN) with t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), (B) five clusters were related to final outcome. Three clusters have better outcomes and two clusters have worse outcomes. These clusters exhibit distinct longitudinal outcomes. Cluster 1 demonstrates low-frequency seizures with delayed remission. Cluster 2 achieves early remission. Cluster 3 shows intermediate-frequency seizures with delayed remission. Cluster 4 experiences decreasing frequency but persistent seizures. Cluster 5 maintains a continuing high seizure frequency.

The clinical characteristics of each cluster. (A) The heatmap was generated based on pairwise comparisons for each variable. Asterisks indicate p-values < 0.05, adjusted using Bonferroni multiple comparison correction. (B) The heatmap illustrated the comparative characteristics, with statistically significant variables displayed on the x-axis. Categorical variables were coded as 1 or 0, representing the presence or absence of the variable, respectively. The proportion of the variable’s presence within each cluster was first calculated and then normalized across clusters for comparison. Red colors indicate the cluster with the highest proportion for each variable. UC Unclassifiable.

Conventional statistical analysis

We performed linear regression analysis, including all datasets. Onset age, febrile seizure history, the presence of epileptiform discharge, the number of initial ASM, structural etiology, and some blood parameters, were associated with the final outcome (Table S2).

Discussion

In this study, we developed algorithms capable of identifying DRE by predicting their final outcomes and identified five clusters associated with the final outcome and subtypes with distinct dynamic clinical courses.

First, we examined AI performance in final outcome prediction. By the RF model, the AUC and ACC were 0.694 and 0.653. A previous study to predict DRE using the claim data from the United States showed an AUC of 0.764 by the RF model12, slightly higher than our result. This study defined ASM resistance as more than three ASM trials. Our binary classification categorizes patients as seizure-free or not in the final year, regardless of the number of ASMs used. Another study13 showed super high performance, with an AUC of 0.979 and an F1 score of 0.947 by the XGB model. The difference in performance from ours might be attributed to the different study populations, including pediatric patients. Additionally, it only included 287 patients. One study with 160 patients, obtained 87.5% accuracy and an AUC of 0.882 to predict the first ASM response using clinical variables and the support vector machine classifier14. This study employed comparable clinical parameters to ours, but its superior performance could be attributed to the enrolment of drug-naïve patients with a relatively shorter follow-up period. Also, a smaller and less heterogeneous population in those studies could result in higher prediction performance. In contrast, our study population consisted of many referred patients with a potentially higher seizure burden. Moreover, the extended follow-up period allows for the observation of varying seizure statuses over time in this cohort (Fig. S1) as well as in other populations4. Predicting the final seizure-free population based on initial fundamental tests is beneficial for counseling patients and facilitates more aggressive treatment strategies. A recent study identified surgical patients early with AUCs of 0.76 and 0.85 in 5,880 pediatric and 7,605 adult cases, respectively15. This group also validated the data in a prospective design, achieving AUCs of 0.91 in both pediatric and adult cohorts16. Their higher performance may be attributed to a relatively focused population, primarily comprising surgical and non-surgical groups. In contrast, our study population is more diverse, including individuals who are medically intractable and eventually underwent surgery, patients who may still benefit from further medical management, and those with intractable generalized epilepsy.

SHAP analysis, the AI technique to explain how much the factors can be involved in the prediction result, demonstrated the relative vital variables to predict the final outcome. Older age at onset and shorter disease duration, the presence of co-medication, and de novo cases occupied the top rank in deciding the AI response algorithm, possibly reflecting the close relationship between the final outcome and the more benign population of epilepsy and older age group with polypharmacy. These findings from the SHAP analysis are also compatible with those from a recently published meta-analysis3. Multiple logistic regression using all datasets showed onset age of epilepsy is independently associated with the final outcome. As a blood parameter, fibrinogen emerged as a factor associated with the final outcome, which is somewhat unexpected. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, our previous study, which analyzed a subpopulation of this cohort using conventional statistical methods, yielded similar findings17. While the exact mechanism remains unclear, one hypothesis had suggested that fibrinogen may exert a neuroinflammatory protective role. In addition, this previous study revealed that higher fibrinogen levels were observed in patients receiving a smaller number of initial ASMs. Therefore, the more favorable outcomes in patients requiring fewer initial ASMs may partly account for the association between higher fibrinogen levels and better prognosis.

From a methodological perspective, SAINT, the DL-based method, did not achieve the best performance in terms of either AUC or ACC and did not show a statistical difference when compared to the RF model. Generally, DL is better suited for analyzing large datasets. However, when the datasets are insufficient to train DL models, achieving satisfactory results can be challenging due to issues such as underfitting or overfitting. Moreover, while DL algorithms have demonstrated significantly higher performance in tasks such as computer vision and natural language processing, studies have shown that ML methods still achieve the highest performance in the analysis of tabular data. In that case, machine learning may perform better than deep learning if your dataset is sparse or the complexity of the characteristics is not significant18,19,20. The outstanding performance of CATB, especially in terms of accuracy, underscores its capability to effectively handle categorical variables, which are prevalent in many forms of tabular data. This model leverages sophisticated algorithms designed to internally handle categorical data without the need for preliminary transformation or encoding that other models might require. By maintaining the integrity of categorical information, CATB can explore more complex interactions and dependencies that might be lost or diluted through conventional encoding methods like one-hot encoding.

We conducted an unsupervised learning-based clustering analysis to categorize epilepsy patients with diverse initial variables. To date, few researchers investigated the dynamic course of seizure using unsupervised ML technique. Some clusters we found are similar to clusters found in previous non-AI research splitting 1098 newly diagnosed epilepsy with four subgroups of distinct clinical courses including ‘early and sustained seizure freedom’, ‘delayed but sustained seizure freedom’, ‘fluctuation’, and ‘seizure freedom never attained’4. Cluster 5 in our analysis exhibited a pattern similar to 'never attaining seizure freedom,' while cluster 2 resembled 'early and sustained seizure freedom’. Uniquely, we employed an unsupervised technique, allowing us to discern differences in dynamic disease courses among the subtypes. A notable advantage of this method is that it classified subtypes without applying clinical weighting to the variables, allowing for an analysis that captures complex relationships among various factors and their relationships that would be challenging to discern from a purely clinical perspective.

We classified the population into three clusters with better outcomes, indicating a statistically higher proportion of seizure-free individuals, and two clusters predominantly associated with poorer outcomes. Among the clusters with better outcomes, cluster 1 is characterized by the presence of generalized spike-and-wave discharges and a genetic etiology, while cluster 2 exhibits traits linked to infectious or immunologic origins. While genetic testing is not routinely performed in all patients, our study classified not only patients with genetic but also those with idiopathic generalized epilepsy within the genetic group, hence the observed distribution. Despite excluding cases of acute seizures from infectious or autoimmune encephalitis, patients classified as having postinfectious or autoimmune epilepsy displayed a notably rapid and sustained positive clinical course. Cluster 3 exhibited cerebromalacia or regional atrophy on MRI, accompanied by generalized intermittent slowing on EEG. These features seem to align with post-stroke epilepsy, as suggested by existing literature highlighting the generally favorable outcomes associated with this condition.

The two clusters associated with poorer outcomes also exhibited unique features. Cluster 4 included patients with epilepsy-associated tumors and focal spike-and-wave and focal slowing on EEG. Cluster 5 was characterized by HS and migration disorders other than FCD. In comparison to the generalized epilepsy and postimmune/postinfectious etiology groups, the two poorer-outcome clusters, those with HS, or tumors, exhibited worse prognoses, findings consistent with current literature and clinical experience. Interestingly, among the poor-outcome clusters, the group characterized by tumors and focal spike-and-wave discharges on EEG demonstrated an initial partial improvement in seizure frequency. In contrast, the HS group experienced a persistently high seizure burden without such reduction, highlighting that this differential trajectory between the two clusters represents a novel and significant finding.

Limitations

The longitudinal outcome of epilepsy can vary significantly depending on the choice and appropriateness of ASM treatments. However, in this study, we did not consider ASM status when assessing dynamic seizure outcomes. Additionally, it may also be influenced by the clustering pattern21,22. Despite this limitation, our cohort consisted of a relatively homogenous group of patients with similar treatment experiences and standards of care, reducing the likelihood of substantial variability in ASM administration due to external factors. Therefore, the influence of ASM regimens is likely to have been uniform across the cohort. Although it remains challenging to account for uniform drug effects in real-world studies, further stratification of larger cohort datasets could mitigate these issues. Moreover, considering the dynamic progression of epilepsy, future research incorporating time-based clinical data has the potential to improve predictive accuracy.

Another limitation of this study is that the cohort included both de novo and referred patients. Although referred cases were significantly more frequent in Cluster 5, other clinical factors also exerted independent influences, indicating that their contribution remains meaningful. Restricting the analysis exclusively to de novo patients might have provided a more homogeneous population and allowed clearer delineation of clinical phenotypes. However, as our hospital is a tertiary referral center, de novo patients accounted for only 31.9% of the study population, and limiting the analysis to this subgroup would have markedly reduced the sample size for clustering. Such reduction may have limited the robustness of the analysis and obscured potentially meaningful findings.

Another limitation involves the definition of infectious or immune etiologies, which include autoimmune-associated epilepsy (AAE). Previous proposals have suggested that seizures in the context of autoimmune encephalitis associated with intracellular antibodies may be defined as epilepsy irrespective of the observation period, whereas in surface antibody–associated encephalitis, a follow-up duration of 1–2 years has been recommended before establishing the diagnosis of epilepsy23,24. In our study, however, patients with both intracellular and surface antibody–mediated encephalitis were included, making it unfeasible to uniformly apply a 1- or 2-year cutoff across the entire cohort. Therefore, we pragmatically defined immune etiology to include autoimmune-associated cases with persistent seizures beyond the acute phase, specifically after completion of immunotherapy and in the absence of MRI abnormalities suggestive of active encephalitis. In addition, for postinfectious epilepsy, we applied the same pragmatic principle, considering seizures as epilepsy when they persisted beyond the acute phase and after the completion of antibiotics therapy.

There was a limitation in AI methods as well. Both ML and DL algorithms heavily rely on not only dataset size but also dataset complexity25,26. Furthermore, the selection process for unsupervised clustering in this study, which prioritized high-performing patients from supervised classification tasks, may introduce a selection bias. By focusing only on patients with the highest classification accuracy, we might have inadvertently excluded certain patient profiles, potentially limiting the generalizability of the clustering results. Future studies should explore methods to minimize such biases, such as employing broader sampling strategies or testing alternative clustering approaches.

Nevertheless, the strength of this study is that this cohort comprises a relatively large number of patients without selection bias of enrollment and has detailed seizure records and meticulous epilepsy evaluations, compared to the previous study population of AI prediction.

Conclusion

The optimal classification strategy for epilepsy remains undetermined. However, employing multiple comprehensive initial variables for classification enhances our ability to predict outcomes by leveraging diverse aspects of the disease. Recognizing multifaceted data structures is imperative, as defining subtypes in epilepsy contributes to more homogeneous outcomes within each group. Identifying a patient’s specific cluster, combined with an understanding of their dynamic course, provides valuable insights into their overall prognosis and may contribute synergistically to the development of personalized treatment strategies.

It is hoped that our data-driven approach using AI to predict the subtypes fitting longitudinal course will enable even further performance improvement with an enormous database in combination with more detailed seizure records by wearables and pave the way for refining epilepsy treatment strategies through future prospective studies.

Methods

The process of cohort establishment

Our cohort, SERENADE (Seoul national university hospital adult Epilepsy Retrospective cohort in the Era of Newer Antiseizure Drug Exposure), comprises 2586 consecutively and retrospectively collected adult patients and their data. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a first visit to the experts of adult epileptology from 2008 to 2017, (2) a diagnosis of epilepsy based on the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definition27, and (3) 3 years or more of follow-up. This study was approved by the Seoul National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (H-2102-178-1200) (H-2308-010-1455) and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written consent was waived due to the retrospective design (IRB number: H-2102-178-1200, H-2308-010-1455).

Data collection and cohort structures

The patients’ lists and laboratory results were extracted from the clinical database warehouse in our institution. Additionally, investigators reviewed electronic medical records thoroughly, including sex, onset age, number of seizures before ASM initiation, de novo versus referred case, seizure types, epilepsy classification, etiology, history of febrile convulsion, family history of epilepsy, comorbidities, co-medications (other than ASMs), and epilepsy surgery history. Detailed seizure occurrences were recorded homogenously at every visit to the clinic or admission. The intervals of outpatient clinics vary according to the patient’s circumstances, but the usual interval was 3 or 6 months. Laboratory results, including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, eosinophil, basophil, absolute neutrophil counts, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, protein, albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, calcium, phosphorus, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, uric acid, Na/K/Cl, tCO2, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, and total cholesterol, were collected when sampled within 90 days from a first visit. Routine blood data fulfilling the time criterion were available for 1782 (68.1%) patients. Among the total patients, 608 (39.8%) were sampled within 1 week of the most recent seizure, 539 (35.3%) between 1 week and 1 month, and 379 (24.8%) more than 1 month after the seizure. Regarding treatment status, 944 of 1,782 patients (53.0%) were using ASMs at the time of sampling.

EEGs were available in 2342 (90.6%) patients. MRI scans with an epilepsy-specific protocol in our institution could be obtained for 2036 (78.7%) patients. Surgical intervention, including resective operation and vagal nerve stimulation, was performed in 72 patients (2.8%).

Dataset for AI analysis

In total, there were 84 categories, including 19 clinical, 33 blood parameters, 18 MRI-related, and 14 EEG-related features. Clinical variables included sex, onset age of epilepsy, epilepsy duration, number of seizures before ASM initiation, de novo or referred, seizure types (generalized, focal), history of febrile convulsion, family history of epilepsy, presence of comorbidities, presence of co-medication, three epilepsy classifications (generalized, focal, combined), and six etiologies (structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, hypoxic, and immune). MRI findings were coded according to the lesion most relevant to the patient’s epilepsy by a consensus of three experienced epileptologists (KIP, SH, SKL) referring to the radiologist’s report. In patients who underwent surgery, when there was a discrepancy between the pathologic and the radiologic diagnosis, the coding was done based on the pathologic diagnosis. The categories are as follows; HS, tumor, FCD, vascular anomaly, cerebromalacia, tuberous sclerosis, other migration disorders, supratentorial cyst, subdural hemorrhage/hygroma, hypoxic-ischemic insult, Sturge-Weber syndrome, calcified lesion, regional atrophy, encephalitis-related, others including vasculitis, demyelinating, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and multiple sclerosis and undetermined. The presence of potential epileptogenic lesions was added as a feature.

EEG coding was performed based on the first EEG during the entire duration, regardless of the routine sleep & waking EEG (30-min session) or video-EEG (at least 24-h session). EEG features were divided into epileptiform discharges and irregular slow waves. Epileptiform discharges were classified into rhythmic spike-and-wave, sporadic spike-and-wave, rhythmic delta activity, and periodic discharge on the generalized or focal area. Irregular slow waves were coded with four features, including generalized continuous, generalized intermittent, focal continuous and focal intermittent slow waves. Two additional parameters, the presence of epileptiform discharges and irregular slow waves, were also included for analysis. All parameters were summarized in Table S1.

Outcome labeling for AI analysis

The final outcome was defined by seizures during the last year of follow-up, which was divided into seizure-free (SF) or not (NSF). To enhance clarity, a flow diagram summarizing the outcome definition and labeling procedure is provided as Fig. S2. Various ML approaches, such as tree-based classifiers, i.e., random forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), LightGBM (LGB), and CatBoost (CATB), were used. As a DL approach, self-attention and intersample attention transformer (SAINT), a specialized architecture for learning with tabular data28, was selected.

In preparation for subsequent experiments and to facilitate easier interpretation and statistical analysis, categorical data were preprocessed using one-hot encoding. One-hot encoding is a process used to convert categorical variables into a binary matrix representation, where each category is represented by a binary vector with only one element set to 1 (hot) and the rest set to 0 (cold). This allows categorical data to be represented in a format that can be easily understood and processed by machine learning algorithms29. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 3:1:1 ratio using stratified random splitting, ensuring that the distribution of patients according to their initial ASM prescription was preserved across the sets. This approach did not involve developing separate models for each ASM, but rather aimed to prevent imbalance in ASM distribution between datasets. To address the issue of missing data and to enhance the performance of our classifiers, we employed the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) technique. MICE is a robust imputation method that provides better estimates by modeling each feature with missing values as a function of other features in an iterative round-robin fashion. This approach is particularly advantageous for handling missing in both categorical and continuous variables by utilizing all available data points to generate plausible values30.

Unsupervised clustering was conducted on a selected cohort of patients, chosen based on their performance in supervised classification tasks. The selection criteria were refined by aggregating prediction results from 100 independent iterations of the supervised XGB model, each using different random seeds. From the entire pool of predictions across all iterations, we selected the 500 SF patients and 500 NSF patients with the highest prediction accuracy. These 1,000 patients were then used for the clustering analysis. This tailored approach enables a more nuanced exploration of data patterns among high-performing patients in both categories.

This decision to focus on well-performing patients under supervised learning conditions is rooted in the complexities associated with unsupervised learning, which typically benefits from clearer and more delineated data patterns to form meaningful clusters. By concentrating on these specific groups of patients, we aimed to enhance the robustness and relevance of our unsupervised clustering outcomes. This methodological refinement helps to minimize the risk of noise and ambiguity in the unsupervised learning phase, thereby maximizing the potential for deriving actionable insights applicable to similarly well-defined patient groups. This decision to focus on high-confidence patients from the supervised phase is supported by previous findings that unsupervised clustering is highly sensitive to noisy or uncertain samples, particularly in high-dimensional medical datasets31. Filtering by prediction confidence can be regarded as a semi-supervised preselection step, which has been shown to enhance robustness, reduce outlier influence, and improve cluster interpretability in both theoretical and applied contexts32,33.

For clustering, categorical variables were transformed by one-hot encoding for mixed data clustering. As a result, a total of 84 variables that consists of 36 continuous and 48 categorical variables were provided as input. Hierarchical density based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN)34 was used for the investigation of clustering. Gower distance35 and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE)36 were used for similarity measurement between data points and visualization with dimension reduction, respectively. Chi-squared continuity was used to determine which clusters had statistically significant differences in the NSF ratio37. Statistical comparisons were then performed between each cluster and the rest of the clusters to identify their unique characteristics.

The area under the curve (AUC), accuracy (ACC), F1 score, true positive ratio (TPR), true negative ratio (TNR), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were derived as an evaluation matrix. For an additive explanation of the AI results, the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) method and conventional statistics were also applied.

Observation of seizure frequency changes based on unsupervised clustering

We documented seizure frequency for each patient to analyze the patterns of changes across different clusters. Initially, we performed linear interpolation for each patient, ensuring that the data is complete and can accurately represent the trends over time. Considering that each cluster contains a mix of SF and NSF patients and the number of subjects in each cluster may not be large, making the clusters potentially vulnerable to noise, we conducted an inter-patient correlation analysis to identify and remove outliers. Outliers were defined based on the correlation of seizure frequency changes compared to other patients, specifically removing any data points where the correlation threshold was on average below 0.1. This methodological approach enhances the robustness of our findings by minimizing the influence of noise and ensuring that the observed trends in seizure frequency accurately reflect genuine cluster characteristics, rather than being skewed by anomalies in data collection or individual patient variability. A schematic overview of this procedure is provided in Fig. S3.

Statistical analysis

The numerical values are expressed as numbers or mean ± standard deviation. When the data did not follow a normal distribution, the median and interquartile values are shown. To identify significant factors (p < 0.05), a Chi-squared test for categorical variable and independent t-test or Mann‒Whitney test was utilized according to the data normality, assessed using the Shapiro test. ML and DL analysis were conducted on Python 3.9.12. Also, SPSS (version 25, IBM, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for the multiple logistic analysis. For the cluster analysis, five clusters were selected based on a statistically significant prevalence of either SF or NSF cases. Collinearity among features was addressed by excluding variables with a correlation coefficient > 0.8 or a variance inflation factor > 5. ANOVA was conducted across variables, followed by two-tailed Bonferroni correction post hoc tests to evaluate differences between clusters identified through unsupervised analysis, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. GraphPad Prism (version 9, Dotmatics, San Diego, CA, United States) and Inkscape (https://inkscape.org/), were used for graph drawing and editing.

Data availability

The de-identified dataset generated and analyzed in this study (clinical, EEG, MRI, and laboratory features) will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and after approval from the appropriate institutional review board. All analysis code for data preprocessing, modeling, and clustering will be made publicly available upon acceptance at: https://github.com/Medical-Vision-Lab/Clustering-in-AED-epilepsy.

References

Cheval, M. et al. Early identification of seizure freedom with medical treatment in patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis. J. Neurol. 270, 2715–2723, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-023-11603-7 (2023).

Zvi, I. B. et al. Children with seizures and radiological diagnosis of focal cortical dysplasia: Can drug-resistant epilepsy be predicted earlier?. Epileptic Disord. 24, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1684/epd.2021.1368 (2022).

Sultana, B. et al. Incidence and prevalence of drug-resistant epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 96, 805–817. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011839 (2021).

Brodie, M. J., Barry, S. J., Bamagous, G. A., Norrie, J. D. & Kwan, P. Patterns of treatment response in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Neurology 78, 1548–1554. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563b19 (2012).

Valderrama, M., Nikolopoulos, S., Adam, C., Navarro, V. & Le Van Quyen, M. In XII Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing 2010: May 27–30, 2010 Chalkidiki, Greece 77–80 (Springer).

Mirowski, P., Madhavan, D., LeCun, Y. & Kuzniecky, R. Classification of patterns of EEG synchronization for seizure prediction. Clin. Neurophysiol. 120, 1927–1940 (2009).

Sinha, N. et al. Structural brain network abnormalities and the probability of seizure recurrence after epilepsy surgery. Neurology 96, e758–e771. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000011315 (2021).

Gleichgerrcht, E. et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy surgical outcomes can be inferred based on structural connectome hubs: A machine learning study. Ann. Neurol. 88, 970–983. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25888 (2020).

Memarian, N., Kim, S., Dewar, S., Engel, J. Jr. & Staba, R. J. Multimodal data and machine learning for surgery outcome prediction in complicated cases of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Comput. Biol. Med. 64, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2015.06.008 (2015).

Hong, S. J., Bernhardt, B. C., Schrader, D. S., Bernasconi, N. & Bernasconi, A. Whole-brain MRI phenotyping in dysplasia-related frontal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 86, 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000002374 (2016).

He, X. et al. Presurgical thalamic “hubness” predicts surgical outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 88, 2285–2293. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004035 (2017).

An, S. et al. Predicting drug-resistant epilepsy—A machine learning approach based on administrative claims data. Epilepsy Behav. 89, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.10.013 (2018).

Yao, L. et al. Prediction of antiepileptic drug treatment outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy by machine learning. Epilepsy Behav. 96, 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.04.006 (2019).

Lee, D. A., Lee, H. J., Park, B. S., Lee, Y. J. & Park, K. M. Can we predict anti-seizure medication response in focal epilepsy using machine learning?. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 211, 107037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.107037 (2021).

Wissel, B. D. et al. Early identification of epilepsy surgery candidates: A multicenter, machine learning study. Acta Neurol Scand 144, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13418 (2021).

Wissel, B. D. et al. Early identification of candidates for epilepsy surgery: A multicenter, machine learning, prospective validation study. Neurology 102, e208048. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000208048 (2024).

Park, K. I. et al. Prognostication in epilepsy with integrated analysis of blood parameters and clinical data. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185517 (2024).

Tharwat, M. et al. Colon cancer diagnosis based on machine learning and deep learning: Modalities and analysis techniques. Sensors 22, 9250 (2022).

Magnini, B., Lavelli, A. & Magnolini, S. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference. 2110–2119.

Shwartz-Ziv, R. & Armon, A. Tabular data: Deep learning is not all you need. Inf. Fusion 81, 84–90 (2022).

Proix, T. et al. Forecasting seizure risk in adults with focal epilepsy: A development and validation study. Lancet Neurol. 20, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30396-3 (2021).

Karoly, P. J. et al. Cycles in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00464-1 (2021).

Rada, A. & Bien, C. G. What is autoimmune encephalitis-associated epilepsy? Proposal of a practical definition. Epilepsia 64, 2249–2255. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17699 (2023).

Geis, C., Planaguma, J., Carreno, M., Graus, F. & Dalmau, J. Autoimmune seizures and epilepsy. J. Clin. Investig. 129, 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI125178 (2019).

Jan, B. et al. Deep learning in big data analytics: A comparative study. Comput. Electr. Eng. 75, 275–287 (2019).

Willemink, M. J. et al. Preparing medical imaging data for machine learning. Radiology 295, 4–15 (2020).

Scheffer, I. E. et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 58, 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13709 (2017).

Somepalli, G., Goldblum, M., Schwarzschild, A., Bruss, C. B. & Goldstein, T. Saint: Improved neural networks for tabular data via row attention and contrastive pre-training. arXiv preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2106.01342 (2021).

Harris, S. & Harris, D. Digital Design and Computer Architecture (Morgan Kaufmann, 2015).

Van Buuren, S. & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

García-Escudero, L. A., Gordaliza, A., Mayo-Iscar, A. & San Martín, R. Robust clusterwise linear regression through trimming. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 54, 3057–3069 (2010).

Chapelle, O., Schölkopf, B. & Zien, A. In Semi-supervised Learning 473–478 (MIT Press, 2006).

Xie, J., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 478–487 (PMLR).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Astels, S. hdbscan: Hierarchical density based clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2, 205 (2017).

Gower, J. C. A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics, 857–871 (1971).

Van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9 (2008).

Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis Vol. 792 (Wiley, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (RS-2023-00265638)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI.P. and SK.L. conceptualized and designed the study. KI.P., S.H., Y.S., YJ.K., SB.L., H.S., MK.K., YG.K., and SK.L. contribute to data acquisition and analysis. KI.P., J.M., ST.L., KH.J., K.C,. KY.J., YG.K., and SK.L. contribute to data interpretation. KI.P., YJ.K., and H.S. draft the work. KI.P., S.H., Y.S., SB.L., J.M., ST.L., KH.J., K.C., KY.J., YG.K., and SK.L. performed critical revision. All authors had full access to the study design information and all data and approved final version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, KI., Hwang, S., Shin, Y. et al. Prediction of longitudinal outcomes and novel cluster identification in epilepsy. Sci Rep 15, 42325 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26360-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26360-y