Abstract

ZnO/M nanocomposites incorporating transition metal oxides (M = CuO, Fe₂O₃, Mn₃O₄) demonstrate significantly tuned functional properties relevant for advanced device applications. Photoluminescence studies reveal modified optical behavior, with all composites showing reduced emission intensity. Blue shifts for Fe2O3 and Mn3O4 composites contrast with a violet shift observed in the CuO composite, reflected in an IB/IV ratio of 1.023, 1.018, and 0.936, respectively. Electrical characterization shows substantially enhanced performance in nanocomposites. Higher dielectric constants and improved AC conductivity values are recorded, particularly in ZnO/CuO samples. Relaxation dynamics shift toward higher frequencies, with peaks in the electric modulus (M’’) observed at 1860 kHz for ZnO/CuO, compared to 100 kHz for pure ZnO, and Cole-Cole analysis confirming non-Debye type behavior. Unique electrical transport emerges in ZnO/Fe2O3, where two successive semicircles in impedance plots suggest complex charge conduction pathways with grain boundary resistance reaching 185 MΩ. Magnetic properties show notable enhancement through composite formation. All nanocomposites exhibit strengthened ferromagnetic character compared to pure ZnO, with saturation magnetization increasing progressively from 0.035 emu/g (ZnO) through 0.039 (ZnO/CuO), 0.050 (ZnO/Fe2O3), to 0.058 emu/g (ZnO/Mn3O4). The materials demonstrate hard magnetic behavior with coercivity values of 70–80 Oe and double exchange interactions dominating, supported by an effective magnetic anisotropy (Keff) increasing from 148 emu·Oe/g for ZnO to 432 emu·Oe/g for ZnO/Mn3O4. These simultaneous improvements across optical, electrical, and magnetic domains position ZnO/M nanocomposites as promising candidates for emerging technologies including spintronic devices, high-frequency telecommunications, and advanced energy storage systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zinc oxide (ZnO) stands as a highly valuable material in modern materials research. Its attractive features include a wide band gap, strong exciton binding energy, and good chemical stability. Researchers widely use ZnO in devices like UV lasers, solar cells, and gas sensors. However, for newer technologies such as spintronics which use the electron’s spin instead of its charge pure ZnO often falls short. It usually shows very weak magnetism at room temperature1,2,3,4.

Recent research has demonstrated that forming nanocomposites with transition metal oxides represents an effective strategy for enhancing and modifying ZnO’s performance characteristics. For instance, studies have shown that dual-doping approaches can simultaneously tailor ferromagnetic and dielectric properties in ZnO nanoparticles for spintronic applications5,6. Similarly, the incorporation of specific transition metals has been shown to modify charge transport mechanisms and enhance room-temperature ferromagnetic interactions in ZnO nanostructures7,8.

For excellent performance in optoelectronics, magnetic data storage, spintronics, magnetic.

For excellent performance in optoelectronics, magnetic data storage, spintronics, magnetic actuators, and solar cells, one-dimensional nanoparticles (NPs) with a high surface-to-volume ratio, more oxygen vacancies (OV), and quantum size confinement have been recommended9,10 To be eligible for such devices, metal-oxide nanocomposites (MONCs) of multiphase must have one, two, or three dimensions smaller than 100 nm. When combined with certain other oxides of 3d-transition metals (TMs), ZnO may need to be precisely adjusted to form unique characteristics of nanocomposite materials, including high OV, big surface area, and strong conductivity, which ultimately adjust their qualities11,12.

Additionally, the integration of ZnO with other metal oxides to form heterostructures represents an effective approach for tailoring material properties beyond the intrinsic limits of single-phase systems. In such nanocomposites, the resulting heterojunction interfaces play a key role in modulating charge carrier dynamics, often leading to superior performance in functional devices. Recent studies on ZnO-based heterostructures highlight their potential in diverse fields, including optoelectronics, catalysis, and energy storage. For instance, the establishment of a p-n junction at the ZnO/CuO interface has been shown to enhance charge separation, making it highly relevant for photovoltaic and sensing applications13,14. Similarly, interfaces in n-n systems like ZnO/Fe₂O₃ can create complex charge transport pathways beneficial for gas sensing and advanced electronics15,16.

On the other hand, with a resistivity of 9.5 Ω.cm at RT, non-stoichiometry of ZnO can lower their energy gap (Eg) to 3.2 eV1,17,18. For spintronic devices, ZnO typically exhibits diamagnetic or poor ferromagnetic behavior at RT (RTFM), which is inconvenient for spintronic devices19. However, interstitial defects and OV are primarily responsible for creating magnetic polarons through the exchange magnetic interaction between OV and the spin of unpaired electrons20,21 However, in the case of TM-doped ZnO, RTFM was created via the exchange interaction between conductive Zn electrons and local d-spin-polarized electrons of 3D transition metals (TMs)22,23. However, the ionic size, valence state, doping content, and magnetic moment of TMs have a major impact on the proper selection of TMs to ZnO24,25 Sadly, the RTFM in doped ZnO has been obtained with a limit concentration of TMs (Co, Mn, Fe, and Ni) that is less than 0.25; nevertheless, the RTFM is destroyed by the super-exchange interaction above 0.25 due to few secondary26,27.

Since inherent defects in ZnO are responsible for the visible photoluminescence (PL) emissions, it can offer a profound understanding of crystallographic flaws, OV, and dangling bonds. The near band edge (NBE) of charge carriers is indicated by the PL band emission in the blue ultraviolet (UV) region, which frequently narrows in a wide band gap (Eg) materials28. For instance, ZnO is perfect for use in cathode-luminescence displays (CLDs) and white light-emitting diodes (LEDs) because of its excellent PL centers resulting from its multicolor emissions29. For this reason, ZnO’s PL is typically characterized by broad-band and strong UV emissions30. Furthermore, faults can produce a variety of colored emissions throughout the visible spectrum31,32 In any event, as the particle size of MONCs approaches the Bohr radius of the excitons, they usually show significant PL intensity due to their enhanced surface-to-volume ratio33.

According to the calculations, the energy needed for defect production has significantly decreased, resulting in mutual interactions that are less expensive in terms of energy28,34. For instance, both pure and TM-doped NPs showed the red28,29. The induced matrix lattice expansion caused by resonant energy transfer between nanomaterials and TMs is the explanation for this behavior29. On the other hand, a generated Ov peak in the core causes a blue shift in the NPs core-shell. Due to the constriction of core-shell development, this may also be described in terms of ascribed strain faults in comparison to the higher strain35,36. However, more information is needed to compare the impact of two distinct groups of TMs added to ZnO as NCs on the PL (two magnetic and one nonmagnetic).

The presence of several valence states for the host lattice of ZnO suggests polar-ionic conduction because of the electrons’ hopping process from lower to higher valence levels37,38. This di-electricity mechanism, described by complicated dielectric parameters against the frequency range up to 10 GHz, is primarily caused by internal faults39,40,41,42,43. High dielectric constant materials are widely known to have drawn particular interest in integrated microwave circuits and mobile phones44,45,46. On the other hand, low dielectric constant materials could be used in nonlinear optical and high-frequency antenna devices47,48,49,50.

Maxwell-Wagner interfacial49,50. The Cole-Cole plots show that conductivity mostly occurs across the grain border and does not contribute through the grains because grain boundary resistance is more common than grain boundary resistance51,52 According to the correlated barrier hopping (CBH) mode, conduction happens via a bi-polaron hopping process in which two electrons concurrently cross the potential barrier between charged defect states53. As a result, single polaron hopping is the main mechanism, and the barrier height is associated with their separation.

Achieving the desired characteristics may necessitate doping ZnO with transition metals (TMs), as this can enable the adjustment of properties such as dielectric constants (ε), dielectric loss (tan δ), and AC conductivity (σac). For example, ε\ and σac of ZnO are significantly decreased by Fe, V, and Mn dopants53,54,55. In contrast, σac increases against frequency (f), and the complex impedance analysis suggests the dominance of grain resistance. The exchange interactions between Zn and TMs are explained by Maxwell-Wagner interfacial polarization and Koops’s phenomenological theory, which explain this behavior. Additionally, the frequency-dependent AC conductivity of NCs follows Jonscher’s power law describing the hopping mechanism of non-Debye relaxation56. In contrast, the increment of σac observed for some of NCs is further required for the efficiency of solar cells46.

CuO is a monoclinic p-type of (1.4–1.65 eV) narrowed indirect Eg, and usually exhibited paramagnetic behavior at RT. It has a low electrical resistivity of 19 (Ω.cm), and therefore, it has been investigated in some advanced electronic devices. It is found that adding Cu to the ZnO host lattice improves its properties57,58. In contrast, Mn3O4 is a tetragonal n-type material with Eg of 2.1 eV and a magnetic moment of 4.9 µB, exhibiting weak paramagnetic behavior. It has an electrical resistivity of 107 Ω·cm at RT in its stoichiometric form. Mn3O4 is not expected to be a source of ferromagnetic domains, but it may be suitable for other applications59,60. On the other hand, α-Fe2O3 is a promising cubic n-type semiconductor due to its wide Eg of 2.2 eV, high chemical stability, and ferromagnetic behavior with a magnetic moment of 3.56 µB. Although α-Fe2O3 is an insulator with an electrical resistivity of 1014 Ω·cm at RT in its stoichiometric form, this resistivity can be reduced by doping with TMs61,62.

These results demonstrated that ZnO’s PL, dielectric medium, and RTFM characteristics remain unclear and require further study, particularly when doped or composited with TMs. The PL, dielectric, and magnetic characteristics of ZnO/M NCs with M = CuO, Fe2O3, and Mn3O4 have been examined with this goal in mind, and the results have been compared with those obtained for ZnO NPs. Although the dielectric and RTFM behaviors of ZnO-NPs are improved when composited with M, the PL intensity is decreased. The composites are to be in the order of ZnO/Mn3O4, ZnO/Fe2O3, ZnO/CuO and ZnO for PL behavior, but the vice is true for dielectric and magnetic behaviors. The correlation behavior between them actually reflects the different and unusual effects of impurities on different properties, which highlights the present investigation.

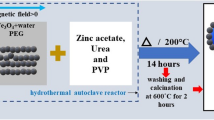

Experimental details

ZnO/M NCs with M = CuO, Fe2O3, and Mn3O4 have been produced utilizing ZnCl2, MnCl2, FeCl3, and NaOH in a hydrothermal process. 20 mL of double-stage distilled water were used to dissolve one mole of each chloride and one mole of NaOH, which were then agitated for 10 min at RT. Using magnetic stirring, NaOH was added to the solutions dropwise and stirred for 60 min, and then they were put in a Teflon container, which was then heated to 453 K for 12 h in a stainless-steel autoclave. Following heating, the items underwent a 3-min, 10,000-rpm intermediate centrifugation before being cleaned with distilled water and acetone. After being cleaned, the composites were crushed, dried for 5 h at 353 K in an oven, and then annealed at 673 K in a furnace. To analyze the nanocrystals (NCs) for phase purity, structural morphology, and elemental composition, an X-ray diffractometer (Philips PW-1700, Netherlands), FEI Quanta 250 scanning electron microscope (SEM), and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy were employed. The XRD data were further refined using the Rietveld method to extract detailed structural parameters. Photoluminescence (PL) measurements at 320 nm were conducted using a Jasco FP-6500 spectrofluorometer equipped with a 150-watt xenon arc lamp as the excitation source. Broadband dielectric spectroscopy (BDS) was used to obtain dielectric measurements with a high-resolution Alpha analyzer equipped with an active sample head (Novo Control GmbH), covering the frequency range from 0.10 to 20 MHz. The pellets were placed between two parallel gold-coated stainless-steel electrodes, each 20 mm in diameter. Fused silica fibers with a diameter of 50 mm served as spacers. Magnetization measurements were performed using a Lakeshore 7400 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), with the magnetic field applied up to 17,300 Oe.

Results and discussions

Structural analysis

The NPs and NCs are arranged to be ZnO, ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Fe2O3, and ZnO/Mn3O4, respectively. The XRD pattern shown in Fig. 1 approved a hexagonal structure for ZnO with a change in the structure of the ZnO/M NCs. Besides the ZnO hexagonal structure, CuO, Fe2O3, and Mn3O4 could be respectively formed in tetragonal, monoclinic, and rhombohedral12. To get a more detailed picture of our crystal structures, we performed Rietveld refinement on the XRD patterns. The refinement plots, which show the measured data, the calculated pattern, and the difference between them, are given in Fig. 1. A good fit is achieved because the difference line (residual) is flat and featureless. For all our samples the residuals are mostly flat, indicating that the structural phases are a strong match for the measured data. The Rietveld refinement gave us a clear look at what’s inside our samples. The Rietveld refinement results in Table 1 confirm we successfully made the composites we intended. Pure ZnO refined nicely, with an R-factor of 7.7. This tells us the crystal structure is a good match for the standard hexagonal ZnO pattern. For the ZnO/CuO composite, the refinement worked even better, giving us our lowest R-factor of 5.8. This is a strong sign that both the hexagonal ZnO and monoclinic CuO phase are present and that our model fits the real data very well. You can see this in the lattice parameters; the a and c values for ZnO in this composite (a = 3.2498 Å, c = 5.2057 Å) are almost identical to pure ZnO, showing that the ZnO structure stayed intact. The ZnO/Mn₃O₄ nanocomposite, the refinement picked up not just ZnO but also a ZnMn₂O₄ phase. The R-factor is a bit higher here at 8.9, which makes sense because fitting two interacting phases is trickier. The fact that it worked confirms we have a nanocomposite, not just a simple mixture. The ZnO lattice in this sample (a = 3.2483 Å, c = 5.2047 Å) shrank just a tiny bit, which could mean some manganese ions squeezed into the ZnO structure. The ZnO/Fe₂O₃ sample was the most challenging. It has the highest R-factor (17) and Chi² (8.3), which points to a more complex structure. The refinement shows that instead of simple Fe₂O₃, a cubic Zn/Fe oxide phase (Fe₀.₇Zn₀.₃) formed alongside ZnO. This new.

Top: The XRD pattern of (a) ZnO NPs and (b) ZnO/CuO, (c) ZnO/Fe2O3, and (d) ZnO/Mn3O4 NCs. The symbols in the figure are Z: ZnO, Cu: CuO, Fe: Fe2O3, Mn: Mn3O4, and ZnMn: ZnMn2 + 3O 412. Below: the Rietveld Refinement of the XRD data of the nanocomposites.

phase, and the bigger change in the ZnO’s lattice parameters (especially the much shorter c-axis at 4.8078 Å), suggests a strong reaction happened between ZnO and Fe₂O₃ during synthesis. This significant structural change is likely the main reason the refinement was harder to fit perfectly.

The crystallite size D is calculated by Scherrer equation (\(\:D=\frac{0.9\lambda\:}{B{cos}\theta\:}\)) based on the three peaks observed for ZnO at (2\(\:\theta\:\) = 31.75o, 34.41o, 36.24o), ZnO/CuO at (31.91o, 34.58o, 36.40o), ZnO/Mn3O4 at (31.73o, 34, 39o, 36.28o) and ZnO/Fe2O3 at (31.72o, 34.36o, 36.21o). The values of \(\:D\) shown in Table 1 are 25.14, 23.49, 25.56, and 26.31 nm for ZnO, and NCs. The \(\:D\:\)is increased by the addition of CuO, Mn3O4 and Fe2O3 to ZnO, respectively. This behavior could be due to the variation of both shape and size of NPs of ZnO/M NCs. In addition, as shown in Table 2, the EDAX confirmed the presence of the considered ions, such that Cu ion is the lower.

ion incorporating Zn (30.03%), which is lower than those of Fe and Mn (68.30 and 46.77%). Interestingly, the wt% of O ions decreased from 28.91% for ZnO to 28.8%, 25.46%, and 4.988% for the composites, indicating that impurity ions help with more OV, especially for Mn. Furthermore, as seen in Fig. 2, the morphology of ZnO, and NCs contains nanoparticles (sheets and spheres) and nanorods. But the ZnO/Fe2O3 NCs consists of only NPs and is nearly free of nanorods12. The particle size (PZnano) of ZnO-NPs was decreased from 118 nm to 98, 87, and 105 nm for the NCs, respectively, whereas the PZrods of nanorods was raised from 283 nm to 522, 699 nm (see Table 2).

Photoluminescence measurements

Figure 3 displays the ZnO and NCs’ PL intensity against wavelength, and Table 2 lists comparable values. In addition to a lower intensity IR emission peak observed for ZnO and ZnO/CuO NCs, three consecutive visible emissions (violet, blue, and green) were recorded. We were unable to detect a discernible shift in the peaks’ wavelengths that would have placed them nearly in the same location (± 6 nm), although their intensities differed greatly. However, the PL intensity is reduced for NCs, and their respective orders are ZnO/Mn3O4, ZnO/Fe2O3, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO. This suggests that more defects are present in NCs, which consequently reduce the PL intensity. Interestingly, the violet and blue spectra recorded between [(413–419 nm); (3.01–2.96 eV)] and [(456–462 nm); (2.72–2.69 eV)] exhibit strong and distinct emissions, respectively. The observed reduction in photoluminescence (PL) intensity in the nanocomposites can be directly linked to the presence of crystal defects, especially oxygen vacancies. These defect states act as non-radiative recombination centers. This means that instead of releasing energy as light, the excited electrons are captured by these traps and lose their energy through other means, primarily as heat through lattice vibrations (phonons). Essentially, the defects introduce a competing pathway for the excited electrons. As the number of defects increases, more electrons choose this non-radiative path over the light-emitting path. This competition effectively quenches the photoluminescence, leading to the significant decrease in PL intensity we observed in all the ZnO/M nanocomposites. The different metal oxides (CuO, Fe₂O₃, Mn₃O₄) likely introduce varying types and densities of these defects, which is why the exact PL behavior, both the intensity drop, and the specific spectral shifts differs between the samples. While collective data from photoluminescence, dielectric, and magnetic measurements strongly suggest the presence of defect states, direct chemical analysis via techniques like X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) would be required in future work to unambiguously identify the specific nature and density of these defects.

The blue emission in ZnO is greater than that of the violet in ZnO/Fe2O3 and ZnO/Mn3O4 NCs since (IB/IV) > 1, which implies a blue shift, but it became violet for ZnO/CuO NCs because (IB/IV) < 1. The energy of violet is between 2.96 and 3.01 eV, which is similar to ZnO, ZnO/CuO and ZnO/Mn3O4 NCs (2.64–3.13 eV), but it is higher than that of ZnO/Fe2O3 (2 eV), such that the Eg has been decreased for NCs12. It is primarily associated with the recombination of (e-h) pairs from localized levels below the CB61,62. The transition of electrons from a shallow donor level of neutral Znni to the highest level of the VB is connected to violet emissions. This suggests that the shallow donor level is situated about 0.19 eV below the CB63. The electrons’ radiative transfer from the shallow Zni donor to the neutral VZn acceptor is due to the centered blue emission64. The third lower peak between [559 and 563 nm] (2.22–2.20 eV) of green emission is attributed to donor-acceptor VZn recombination/or a transition from the CB to oxygen anti-sites due to OV65,66. The observed lowest intensity IR emission peak centered at 823 nm (1.51 eV) is attributed to the excitation of the (3d/4f) lowest energy of the ZnO, similar to TM3+-doped ZnO when excited above Eg, [320 nm (3.88 eV)]67. However, the photoluminescence (PL) of ZnO and its nanocrystals (NCs) can introduce impurities into the bandgap (Eg) of ZnO nanoparticles (NPs), potentially creating multiple impurity levels through multi-ionization processes20,68. The enhanced blue emission for ZnO/Fe2O3 and ZnO/Mn3O4 NCs confirms that Fe and Mn ions are successfully incorporated into ZnO, whereas its lower values for ZnO/CuO NCs may result from a recombination between the electrons in the CB and the holes trapped in the acceptors24,69. We believed that this trend is linked to either valency of Cu2+ as compared to Fe3+ and Mn2+/3+ or the magnetic moments of Fe and Mn ions, rather than the ionic radii of Cu, Fe, and Mn ions, which are close to that of Zn.

Additionally, the band gap energy (Eg) simply can be evaluated from photoluminescence (PL) using the formula Eg = hc/λ = 1241.4/λ (nm). Using the values of λ against the PL peak of UV emission, the values of Eg are 2.94, 2.97, 2.93, and 2.94 for ZnO, ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Fe₂O₃, and ZnO/Mn₃O₄ samples. This behavior indicates that Eg was increased against CuO, but it was nearly unchanged with the addition of Fe₂O₃ or Mn₃O₄.

Dielectric measurements

The real ε′ part of dielectric constant (ε), loss factor (tan δ) and q-factor are given by45,70;

C represents the capacitance of the sample, while C₀ is the capacitance of the empty cell (C₀ = ε₀A/d), where ε’’ denotes the imaginary part of the dielectric constant ε According to Fig. 4a, which plots ε′ against frequency (f), ε\ steadily dropped as f rose until it reached 1 MHz, at which point it saturated. However, the higher values of ε’ at lower frequencies indicate interactions between conductivity contributions and interfacial polarization. As the frequency increases, charge carriers tend to aggregate and generate dipolar polarization in response to the applied field, but they are unable to reverse their orientation when the field reverses71. All of the NCs have orders of ZnO/Fe2O3, ZnO/Mn3O4, and ZnO/CuO, and their ε′ values are greater than ZnO NPs due to the difference of electronegativity between ZnO and NCs, which in turn influences the strength of the ionic bonds and subsequently raises the dielectric polarization43,48. Furthermore, for NCs, a decrease in D and PZ may result in an increase in the number of dipoles, raising ε′ values. Based on the behavior of ε′, the NCs are better suited for integrated microwave circuits and telecommunications than ZnO NPs. The sharp drop in ε′ below 10 kHz, however, is mostly explained by a space charge regime that is roughly 20 nm thick72, and the field in such regime is anticipated to facilitate the de-trapping process and support the ε′ toward a very thin insulating layer. ZnO NPs have interfaces with a volume fraction of roughly 1019 interfaces/cm3, which increased space-charge polarization at low f73. Additionally, a large number of dipoles may develop between O and Ov, resulting in a high ε′ value, as obtained74.

The behavior of ε’’ against f is depicted in Fig. 4b, where ε’’ never reaches saturation but drops linearly with increasing f up to 20 MHz. This is ascribed to the contribution of ion hop and conduction loss of ion migration in addition to ionic polarization at low and moderate f75.

The fluctuation of tanδ against f is displayed in Fig. 4c. As f increases to 100 Hz, the tanδ of ZnO NPs is lower than that of ZnO/Mn3O4 NCs, but it is higher than that of ZnO/CuO and ZnO/Fe2O3. However, as f rises above 100 Hz, it falls below that of NCs. While the NCs displayed relaxation peaks (RPs) at 6.11, 0.295, and 0.0027 kHz, respectively, the ZnO NPs showed no RPs. This indicates a stable condition of the nanocrystals (NCs), rendering them unsuitable to replace ZnO, while showing minimal dynamic activity in dielectric conduction between the electrodes. For the ZnO/Fe₂O₃ and ZnO/Mn₃O₄ NCs, the relaxation peak frequency (f) decreases, primarily due to the hopping mechanism responsible for dc conduction. On the other hand, the RPs for ZnO/CuO NCs are typically shifted to high f by the conduction between localized states in the mobility gap, suggesting that the rate of hopping of localized charge carriers is increasing. Furthermore, the wide distribution of RPs for the NCs points to non-Debye-type behavior in the RPs spread76,77.

The total conductivity (σt) is given by [76]

where s is the frequency exponent, B is a constant, and σdc is the dc conductivity. The AC conductivity (σac) is plotted against f in Fig. 5a for NPs and NCs, in which σac steadily rises as f increases up to 20 MHz. The σac for the NCs is higher than that of ZnO NPs and has the same order of ε’. At a critical f, σac follows the relation (σac ∼ ωs), where s ≤ 1.00 for electronic conduction and s < 0.50 for hole conduction78. The values of s shown in Table 3 are obtained from the linear fit between ln σac and ln ω displayed in Fig. 5b. It is seen that s < 0.50 for all NPs and NCs, indicating hole conduction. The usage of NCs in solar cell design is strongly supported by the greater value of the F-factor for the figure of merit provided by\(F = \frac{{\sigma ^{\backslash } }}{{\varepsilon ^{\backslash } }}\)79. All samples’ F-factor variation with f is shown in Fig. 6, which shows a steady rise in the F-factor as the f increased to 20 MHz. Furthermore, the ZnO NPs F-factor rose for NCs, suggesting that all of them are more qualified than ZnO NPs for solar cell, particularly for ZnO/Mn3O4 at low f (< 10 kHz) and ZnO/CuO at f (> 10 kHz).

Figures 7a&b display the real (M\) and imaginary (M\\) parts of the electric modulus as functions of frequency (f) for the samples. It is observed that M\ increases with increasing frequency for all samples and then reaches a saturation point above 1 MHz, similar to ε′. Compared to pure ZnO, M\ values for the composites are lower below 1 MHz, but beyond this frequency, M\ surpasses that of ZnO. A similar trend is observed for M\\, although with different relaxation peaks (RPs). For example, M\\ shows a RPs at 100 kHz for ZnO and ZnO/Mn3O4, but it shifted to a low f of 32.80 kHz for ZnO/Fe2O3 and to a high f of 1860 kHz for ZnO/CuO. Likewise, Figures. 8a&b illustrate the real (Z\) and imaginary (Z\\) parts of the electric impedance as functions of frequency (f) for the samples. It is evident that at higher frequencies, Z\ values for all samples converge and stabilize, likely due to the dissipation of space charges80.

It is seen that Z\ gradually decreases as f increases and is saturated above 1 MHz. In addition, the Z\ of ZnO increases for ZnO/Fe2O3 composite, but it decreases for the other. A similar trend is observed for Z\\, with relaxation peaks (RPs) appearing at approximately 0.413, 100, (0.0027, 6.111), and 23.40 kHz, respectively. Additionally, Table 4 summarizes the frequencies of these RPs as determined from the curves of tanδ, M\\, and Z\\, indicating that the relaxation peak frequencies can be ranked in the order: M\\, Z\\, and tanδ. While they are arranged relative to samples to be ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Mn3O4, ZnO, and ZnO/Fe2O3.

Assuming that the low-frequency relaxation process has a simple Debye behavior, one can determine its characteristic relaxation time (t) from the frequency against relaxation peaks (f max) of M\\ against f plot, using the equation t = (2ꙥfmax)⁻¹ or using t = (2ꙥfcross)⁻¹, where fcross is the crossing frequency between the M\, and M\\,, which usually separate between the Debye and non-Debye processes81. However, the non-Debye relaxation is a behavior in dielectric materials that deviates from the ideal Debye model, where a system is assumed to have a single relaxation time and instantly loses all memory of relaxation. However, for simplicity we have used the formal one. It is found that the values of t are 1.59, 0.086, 4.85, and 1.59 µs for the ZnO, ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Fe₂O₃, and ZnO/Mn₃O₄ samples, respectively. However, carrier relaxation is the process by which excited charge carriers (electrons and holes) lose energy and return to a lower energy state through various mechanisms, such as carrier-phonon scattering, carrier-carrier scattering, and recombination. Based on the above, the carrier relaxation time is similar for the ZnO and ZnO/Mn₃O₄, whereas the highest value is for ZnO/Fe₂O₃ and the lowest is for ZnO/CuO. Such difference between the samples can be attributed to the disorder and structural complexities in the material.

Figures 9 a&d display the Cole-Cole (Nyquist) plots of Z\\ versus Z\ for all samples. The plots show a spread rather than a perfect semicircle centered on the real axis, characteristic of non-Debye relaxation behavior. This non-Debye response suggests that the relaxation of dipole moments occurs over a distribution of relaxation times82. The figure displays two regions: the grain region at higher frequencies and the grain boundary region at lower frequencies, which are effectively modeled using an equivalent circuit consisting of parallel RC elements. The plots of Fig. 9 a, b & d for ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/Mn₃O₄ samples show single semicircular arcs followed by straight lines or arcs with positive slopes at the tail end. The positive slope suggests an increase in conductivity and implies that a limited number of composite ions may be present at the grain boundaries, potentially facilitating transport across the grain boundaries and promoting grain growth83. In contrast, the plot of Fig. 9cfor ZnO/Fe₂O₃ sample exhibits two consecutive semicircles spanning the frequency range, indicating that the selected frequency range is adequate to distinguish between the conductivities of the grains and the grain boundaries. This behavior was effectively modeled using an equivalent circuit consisting of parallel RC elements, confirming the presence of non-Debye relaxation. The radius and diameter of each plot were used to calculate the first and second impedance components, representing grains and their boundaries as Z\(gf), Z\(gbs), Z\\(gf) and Z\\(gbs), respectively, as summarized in Table 5. It is found that the values of Z\(gf) and Z\(gbf) of ZnO were decreased for the composites, and they have the order of ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Fe2O3 ZnO/Mn3O4. A similar trend was obtained for Z\(gbf), but it has the order ZnO/CuO, ZnO/Mn3O4 and ZnO/Fe2O3. However, the values of Z\(gs) and Z\(gbs) of ZnO/Fe2O3 are 9.5 and 185 MΩ, which are more than those of Z\(gf) and Z\(gbf) (0.224 and 6.11 MΩ). The Z\ a function of f is given by48;

In this equation, RB represents the series resistance, and Ceff denotes the effective capacitance of the parallel equivalent circuit. The intercepts of the linear plot between [1/Z\(ω)] and (ω²) provide the values of RB, while Ceff can be calculated from the slope, as shown in Table 5. The behavior of RB is similar to Z\ for grains and grain boundaries, with values of 5 MΩ, 0.5 MΩ, 14.30 MΩ, and 3.33 MΩ for ZnO and its composites. The values of Ceff are 0.02, 0.283, 0.012, and 0.03 µF, indicating that (Ceff α Z\)84,85. The observed increase in Ceff for ZnO/CuO composites can be attributed to the deformation of micro-capacitors, primarily influenced by factors such as crystallite size (PZ) and porosity introduced by Cu. Interestingly, high-performance lithium-ion batteries typically display low values of RB and Ceff, often characterized by a semicircular shape in the impedance spectrum. This behavior is mainly associated with the oxidation and reduction reactions of lithium ions within the electrode material83. In contrast, a supercapacitor requires a lower RB and a higher Ceff to minimize energy loss associated with the equivalent series resistance86. These findings strongly recommend that the ZnO, ZnO/Fe2O3 and ZnO/Mn3O4 nanocomposites are more suitable for high-power Li- batteries, whereas ZnO/CuO can be used as a supercapacitor, as reported.

Magnetic measurements

Figures 10 display the room temperature (300 K) magnetic hysteresis loops of the samples, showing ferromagnetic behavior with varying saturation magnetizations (Ms). The field up to 2000 Oe is not sufficient to reach complete magnetic saturation for ZnO/Fe2O3 and ZnO/Mn3O4 composites. The Ms is 0.035 (emu/g) for ZnO, but it is increased to 0.039, 0.050, and 0.058 (emu/g) for the composites, respectively. Similar behavior was approved for coercive field Hc, magnetic moment µ = (WMs/5585), remnant magnetization (Mr), area under the curve, and magnetic anisotropy γ = (HcMs/0.98), which are listed in Table 622,87,88. In contrast, squareness Sq = (Mr/Ms) was decreased sequentially, and it is between 0.09 and 0.127 (< < 0.50) for all samples, indicating magneto-static interaction for the studied samples [89,90. The slight increase in Hc for the composites is evidence of hard magnetization91. According to TMs, Ms is follows the order of Zn, Cu, Fe and Mn. The RTFM behaviors for ZnO and ZnO/CuO samples are mainly originated by Zn interstitial sites and Ov, since Zn and Cu ions are nonmagnetic ions. Fe is a ferromagnetic ion and should be a source of strong ferromagnetic as compared to paramagnetic Mn ions, but it is further not obtained. Therefore, the RTFM behaviors can be explained by the following; Firstly, we expected that the change of valence state of Fe3+/2+ or Mn2+/3+ may be the source of the induced ferromagnetic as a result of decreasing Ov, see Table 2. This corresponds to the rise in compensated spins on the surface of the sample compared to the particle core, particularly as the particle size exceeds the constraints of quantum size confinement91,92. Secondly, the ferromagnetism may be attributed to strong magnetic interactions between Fe (3.36 µB) or Mn (4.9 µB) ions and singly ionized oxygen vacancies (Ov) via double-exchange mechanisms24,93,94. These ions are mediated by an electron trapped at the vacancy as well as F-center exchange interactions, which in turn supporting the RTFM88,95. So, as compared to Cu, Fe and Mn ions are able to tune the RTFM of ZnO-NPs to be qualified for spintronic devices25,26,96. In addition, the origin of room-temperature ferromagnetism (RTFM) is not solely attributable to well-known ferromagnetic impurity phases or clusters; other factors such as interstitial sites, oxygen vacancies (Ov), and valence states also play a significant role alongside magnetic moments.

for ZnO-NPs and ZnO/M nanocomposites.

Magnetization at any field M(H) is related to Ms using the following Stoner–Wohlfarth (S–W)97,98;

β is related to the field magnetic anisotropy and it is given by;

Keff represents the effective magnetic anisotropy, and Ha is the anisotropy field. Keff is influenced by variations in magnetic anisotropy sources, which can either strengthen or weaken magnetic interactions within the nanocomposites. Values of the parameters β and Ms are deduced from the slope of the plot of magnetization (M) versus (1/H²), as shown in Figure 11, enabling the calculation of Keff and Ha, which are listed in Table 6. The Keff value is 26,247.26 emu·Oe/g for the ZnO sample but increases progressively in the composites, reaching a maximum of 306,431.07 emu·Oe/g for Fe₂O₃, indicating that Keff is proportional to Ms. Conversely, Ha is 17,144.26 Oe for the ZnO sample and decreases to a minimum of 4,895.06 Oe for the ZnO/Fe₂O₃ composite, demonstrating that Ha is inversely proportional to Ms. Additionally, the values of Ha and Keff are higher than those of Hc and γ, implying that the nanocomposites exhibit hard magnetic characteristics, which in turn influence the electron-spin interaction mechanism97,98,99.

The variation in switching field distribution (SFD) across different angles is crucial for single-domain magnetic particles, determining when each particle flips its magnetization state. This aspect is vital for magnetic recording media, as the anisotropic particles need to align in various field directions. To enhance output quality, it’s recommended to reduce the spin-flip distance (SFD) and keep it at a high level. This would lead to an increased number of reversed states of particle magnetization against H due to reduced demagnetization. The switching field distribution (SFD) is computed by96,98,100;

ΔH represents the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (dM/dH) versus H curve, as illustrated in Fig. 12a,b,c&d. The formation of a singular peak in the SFD plot indicates a dual exchange interaction, showcasing the magnetic connection between cations and anions due to the delocalization of electrons. It also signifies the energy barrier distribution within the nanocomposite, which is associated with a corresponding particle coercivity distribution, such as the optimal bias current and noise99. As listed in Table 6, the SDF of ZnO was decreased for the composites, indicating that barrier energy is inversely proportional to the magnetization parameters, but it has a similar behavior for Sq. In addition, the Ha values are 100–200 and 1500–2500 times higher than those of Hc and SDF.

Summarizing the results obtained for the ZnO/M composites as compared to ZnO (i) decreasing the PL intensity and a violet shift for the ZnO/CuO; increasing the values of ε\, σac and F-factor; decreasing the dielectric loss for ZnO/CuO and ZnO/Fe2O3, but it is increased for ZnO/Mn3O4; shifting the RPs to higher f, especially for ZnO/CuO, whereas it is increased for ZnO/Fe2O3 and ZnO/Mn3O4; decreasing the Z\(g) and Z\(gb) (viii) changing the RB and Ceff; increasing the Ms and most of magnetization parameters; decreasing the Sq. The consistency of these points provides a level of assurance regarding the potential of ZnO/M nanocomposites, making them promising candidates for advanced devices.

The investigated properties in the ZnO/M nanocomposites are correlated through a defect-mediated interplay. The incorporation of transition metal oxides (CuO, Fe₂O₃, Mn₃O₄) introduces oxygen vacancies and creates interfaces, which simultaneously enhance electrical conductivity and room-temperature ferromagnetism by promoting charge hopping and double-exchange interactions. However, these same defects act as non-radiative recombination centers, leading to the observed reduction of photoluminescence intensity. This produces an inverse correlation where the superior functional performance in the electrical and magnetic domains is achieved at the expense of optical emission efficiency. The specific characteristics such as the dielectric properties of ZnO/CuO, the complex impedance of ZnO/Fe₂O₃, and the strongest magnetism in ZnO/Mn₃O₄ are further fine-tuned by the unique cation valency, magnetic moment, and resultant phase composition of each composite, demonstrating the possibility of tailoring these materials for targeted advanced applications.

A key finding from Table 7 is the superior performance of our composites. This is clearly seen in the saturation magnetization (Ms): the ZnO/Mn3O4 and ZnO/Fe2O3 composites exhibit Ms values of 0.058 and 0.050 emu/g. These results are significantly higher by more than an order of magnitude than those reported for ion-doped systems like (Gd, Co) co-doped ZnO. The marked enhancement points to a fundamental conclusion: forming a composite with a discrete magnetic phase is a more productive route to strong ferromagnetism than traditional substitutional doping.

The magnetic stability of these composites is further corroborated by their coercivity (Hc). With Hc values of 72.4, 71.2, and 80.4 Oe, the present composites perform comparably to, or even surpass, other magnetic ZnO systems like (Gd, Co) co-doped ZnO. Such performance indicates the presence of well-defined magnetic domains and effective pinning centers within the composite’s microstructure. A critical distinction for these composites, however, lies in their dielectric properties. They exhibit a high dielectric constant, a feature not emphasized in other high-Ms materials like Fe₃O₄@ZnO/C which are tailored for biomedical applications or in the ZnO–ZnFe2O4 nanocomposite, which is also targeted for spintronics. Even when compared to Sn: ZnO nanoparticles, proposed for high-frequency devices, our composites display a superior dielectric response. This concurrent possession of significant magnetization and high dielectric constant is a pivotal combination for multifunctional applications, particularly in spintronics, where the coupling of magnetic and electric properties is fundamental. In conclusion, the composites developed in this work occupy a unique niche. While they do not exhibit the ultra-high magnetization of iron-oxide-based biomaterials, they offer a more compelling synergy of magnetic and dielectric properties than many doped ZnO systems. This specific property profile renders them strong candidates for advanced spintronic and multifunctional device applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Samanta, A., Goswami, M. N. & Mahapatra, P. K. Magnetic and electric properties of Ni-doped ZnO nanoparticles exhibit diluted magnetic semiconductor in nature. J. Alloys. Compd. 730, 399–407 (2018).

Xiong, Z. et al. Oxygen enhanced ferromagnetism in Cr-doped ZnO films. Appl. Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3624589 (2011).

Techalertmanee, T. et al. Facile synthesis of zinc-iron mixed oxide/carbon nanocomposites as nanocatalysts for the degradation of methylene blue. Mater. Lett. 145, 224–228 (2015).

Wahba, M. A. Synergistic doping of ZnO nanoparticles with Zr and Mn for enhanced room-temperature ferromagnetism and optical modulation. Ceram. Int. 51, 44371–44382 (2025).

Khan, R. et al. Tailoring ferromagnetic and dielectric properties in ZnO via (Eu, Co) doping for spin-based electronic devices. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 36, 795 (2025).

Khan, R. et al. Carrier-mediated ferromagnetism and dielectric tailoring in dual-doped ZnO semiconductor nanoparticles for spintronics. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 193, 109487 (2025).

Khan, R. et al. Charge transport and ferromagnetic interactions in Ti double-doped ZnO nanorods for spin electronic applications. J Saudi Chem. Soc. 29(1), 4 (2025).

Mahmood, M. A. et al. Diluted magnetic semiconductor behavior in Co- and Gd-co-doped ZnO nanotubes for spintronic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 1–13 (2023).

Jiang, J., Pi, J. & Cai, J. The advancing of zinc oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications.. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1062562 (2018).

Somasundaram, G., Rajan, J., Sangaiya, P. & Dilip, R. Hydrothermal synthesis of CdO nanoparticles for photocatalytic and antimicrobial activities. Results Mater 4, 100044 (2019).

Sharma, A. K. et al. The selective ethanol gas sensing performance of CdO1 – XZnOX nanocomposite. J Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 28, 3752–3761 (2017).

Mohamed, M., Jayiz, M., Alshammari, A. S., Sedky, A. & Khan, Z. R. Comparative study on structural, morphological, optical and photocatalytic properties of Mn3O4/ZnO, CuO/ZnO and Fe2O3/ZnO nanocomposites. Opt Quantum Electron 55(6), 562 (2023).

Alwash, A. Green fabrication of p-n CuO/ZnO heterojunctions for efficient photocatalytic degradation of dyes. South. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 54, 441–450 (2025).

Kant, R., Pathak, S. & Dutta, V. Design and fabrication of sandwich-structured α-Fe2O3/Au/ZnO photoanode for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Sol Energy Mater. Sol Cells. 178, 38–45 (2018).

Chakraborty, U. et al. Zinc oxide-copper sulfide semiconductor nano-heterostructure for low-level electrochemical detection of 4-nitrotoluene. Electrochim. Acta. 447, 142160 (2023).

Bhoi, Y. P. & Mishra, B. G. Single step combustion synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic application of Α-Fe2O3-Bi2S3 heterojunctions for efficient and selective reduction of structurally diverse nitroarenes. Chem. Eng. J. 316, 70–81 (2017).

Shi, Y., Liu, Q. G., Chen, Y. & Wang, M. H. Structure, optical and varistor properties of one-dimensional co-doped zno synthesized by reflux method. J Electron. Mater 50(10), 5891 (2021).

Mohamed, M., Sedky, A., Alshammari, A. S. & Gandouzi, M. Optical, photoluminescence and ferromagnetic properties of Ni-doped ZnO for optoelectronic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32, 5186–5198 (2021).

Bomila, R., Srinivasan, S., Gunasekaran, S. & Manikandan, A. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye, opto-magnetic and antibacterial behaviour of pure and la-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 31(3), 855–864 (2018).

Manikandan, A. et al. Rare earth element (REE) lanthanum doped zinc oxide (La: ZnO) nanomaterials: Synthesis structural optical and antibacterial studies. J Alloys Compd 723, 1155–1161 (2017).

Mohamed, M. et al. Structural, FTIR, optical, mechanical and magnetic properties of Zn1 – xFexO with various Fe nanopowder additions. Appl Phys. Mater. Sci. Process 128(5), 408 (2022).

Sedky, A., Ali, A. M., Algarni, H. & Structural,. FTIR, optical and magnetic investigation of Zn1 – xMxO ceramics with M = Cu, Mn: Comparative study. J Alloys Compd 912, 165439 (2022).

Sharma, D. & Jha, R. Transition metal (Co, Mn) co-doped ZnO nanoparticles: Effect on structural and optical properties. J. Alloys. Compd. 698, 532–538 (2017).

Sedky, A., Afify, N., Almohammedi, A., Ibrahim, E. M. M. & Ali, A. M. Structural, optical, photoluminescence and magnetic investigation of doped and Co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 55(5), 456 (2023).

Sedky, A. et al. Annealing temperature effect on structural, mechanical, and magnetic properties of Cd0.40M0.60ZnO2 (M = Mn, Ni) nanocomposites. Mater Chem. Phys 309, 128326 (2023).

Abbady, G., Afify, N., Sedky, A. & Hamad, D. Effect of annealing temperature on structural, optical and magnetic properties of Cd1-xMnxZnO2 nanocomposites: An investigation for ferromagnetic. Ceram Int 49(11), 18042–18054 (2023).

Zhang, J., Li, X. Z., Shi, J., Lu, Y. F. & Sellmyer, D. J. Structure and magnetic properties of Mn-doped ZnO thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/19/3/036210 (2007).

Xu, X. & Cao, C. Structure and ferromagnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO powders. J Magn. Magn. Mater 321(14), 2216–2219 (2009).

Rhouma, F. I. H. et al. The structure and photoluminescence of a ZnO phosphor synthesized by the sol gel method under praseodymium doping. RSC Adv 9, 5206–2517 (2019).

Chanthima, N., Boonin, K., Limsuwan, P. & Kaewkhao, J. Visible luminescence of Pr3 + in bismuth Borate glasses. in Adv Mater. Res 770, (2013).

Dheyab, M. A., Aziz, A. A., Jameel, M. S. & Oladzadabbasabadi, N. Recent advances in synthesis, modification, and potential application of tin oxide nanoparticles.. Surfaces Interfaces 28, 101677 (2022).

Sedky, A., Amin, S. A. & Mohamed, M. Electrical, photoluminescence and ferromagnetic characterization of pure and doped ZnO nanostructures. Appl Phys. Mater. Sci. Process 125(5), 308 (2019).

Sedky, A., Ali, A. M., Somaily, H. H. & Algarni, H. Electrical, photoluminescence and optical investigation of ZnO nanoparticles sintered at different temperatures. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 53(5), 243 (2021).

Poornaprakash, B., Chalapathi, U., Subramanyam, K., Vattikuti, S. V. P. & Park, S. H. Wurtzite phase Co-doped ZnO nanorods: Morphological, structural, optical, magnetic, and enhanced photocatalytic characteristics. Ceram Int 46(3), 2931–2939 (2020).

Ahmed, A., Naseem Siddique, M., Alam, U., Ali, T. & Tripathi, P. Improved photocatalytic activity of Sr doped SnO2 nanoparticles: A role of oxygen vacancy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 463, 976–985 (2019).

Hosseini, S. M., Sarsari, I. A., Kameli, P. & Salamati, H. Effect of Ag doping on structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties of ZnO nanoparticles. J. Alloys. Compd. 640, 408–415 (2015).

Ghosh, R., Giri, P. K., Imakita, K. & Fujii, M. Photoluminescence signature of resonant energy transfer in ZnO coated Si nanocrystals decorated on vertical Si nanowires array. J. Alloys. Compd. 638, 419–428 (2015).

Jiang, D. et al. Synthesis and luminescence properties of core/shell ZnS:Mn/ZnO nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 4(1), 78 (2009).

Mohamed, M. et al. Structural, morphological, optical, photocatalytic activity investigations of Bi doped ZnO nanoparticles. Opt Mater. (Amst) 136, 113347 (2023).

Sahay, P. P., Tewari, S., Nath, R. K., Jha, S. & Shamsuddin, M. Studies on ac response of zinc oxide pellets. J Mater. Sci. 43(13), 4534–4540 (2008).

Sedky, A., Afify, N., Ali, A. M. & Algarni, H. FTIR, optical and photoluminescence investigation of Zn1-xRExO nanoparticles for optical and power operation devices. J. Electroceramics. 49(2), 33–52 (2022).

Sedky, A., Ali, A. M. & Algarni, H. FTIR, optical and dielectric properties of Zn1-xAlxO ceramics for advanced applications. Opt. Quantum. Electron. 54(6), 376 (2022).

Saadi, H. et al. Electrical conductivity improvement of Fe doped ZnO nanopowders. Mater Res. Bull. 129, 110884 (2020).

Singh, S., Dey, P., Roy, J. N. & Mandal, S. K. Tunable dielectric constant with transition metals doping in Zn1-x(MnTM)xO (TM = Co, Fe) nanocrystals. J. Alloys. Compd. 642, 15–21 (2015).

Zamiri, R., Kaushal, A., Rebelo, A. & Ferreira, J. M. F. Er doped ZnO nanoplates: Synthesis, optical and dielectric properties. Ceram. Int. 40(1), 1635–1639 (2014).

Irshad, K., Khan, M. T. & Murtaza, A. Synthesis and characterization of transition-metals-doped ZnO nanoparticles by sol-gel auto-combustion method. Phys. B. Condens. Matter. 543, 1–6 (2018).

Omri, K., Bettaibi, A., Khirouni, K. & El Mir, L. The optoelectronic properties and role of Cu concentration on the structural and electrical properties of Cu doped ZnO nanoparticles. Phys. B Condens. Matter. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2018.02.025 (2018).

Singh, J. & Singh, R. C. Structural, optical, dielectric and transport properties of ball mill synthesized ZnO–V2O5 nano-composites. J Mol. Struct 1215, 128261 (2020).

Acharya, A. D. & Sarwan, B. Tunability of electronic properties and magnetic behaviour of nickel oxide: a review. Curr. Nanosci. 15, 354–370 (2018).

Manjula, N. et al. Synthesis, structural and electrical characterizations of SnO2 nanoparticles. Int J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 9, 141–156 (2016).

Parveen, A., Ahmad, S. A., Agrawal, S. & Azam, A. Room temperature variation in dielectric and electrical properties of Mn doped SnO2 nanoparticles. in Mater. Today Proc. 4, (2017).

Ahmed, A., Tripathi, P., Siddique, M. N., Ali, T. & Microstructural Optical and dielectric properties of Al-Incorporated SnO2 nanoparticles. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 225, 12173 (2017).

Muy, S., Schlem, R., Shao-Horn, Y. & Zeier, W. G. Phonon–ion interactions: designing ion mobility based on lattice dynamics.. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 15–2002787 (2021).

Gupta, R. et al. Advances in micro and nano-engineered materials for high-value capacitors for miniaturized electronics.. J. Energy. Storage. 55, 105591 (2022).

Ben Taher, Y., Oueslati, A., Maaloul, N. K., Khirouni, K. & Gargouri, M. Conductivity study and correlated barrier hopping (CBH) conduction mechanism in diphosphate compound. Appl Phys. Mater. Sci. Process. 120(4), 1537–1543 (2015).

Singh, J. & Singh, R. C. Tuning of structural, optical, dielectric and transport properties of Fe-doped ZnO:V system. Mater Sci. Semicond. Process 121, 105305 (2021).

Radhakrishnan, A. A. & Beena, B. B. Structural and optical absorption analysis of CuO nanoparticles. Indian J. Adv. Chem. Sci 2, (2014).

Shaban, M., Abdelkarem, K. & El Sayed, A. M. Structural, optical and gas sensing properties of Cu2O/CuO mixed phase: effect of the number of coated layers and (Cr + S) co-Doping. Phase Transitions 92(4), 347–359 (2019).

Zhao, J. et al. Energy-efficient fabrication of a novel multivalence Mn3O4-MnO2 heterojunction for dye degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 202, 509–517 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. Valence state heterojunction Mn3O4/MnCO3: Photo and thermal synergistic catalyst. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 180, 6–12 (2016).

Seo, O. et al. Tuning of structural, optical band gap, and electrical properties of room-temperature-grown epitaxial thin films through the Fe 2 O 3:NiO ratio. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 4304 (2019).

Qayoom, M., Shah, K. A., Pandit, A. H., Firdous, A. & Dar, G. N. Dielectric and electrical studies on iron oxide (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles synthesized by modified solution combustion reaction for microwave applications. J. Electroceramics. 45(1), 7–14 (2020).

Layek, A., Banerjee, S., Manna, B. & Chowdhury, A. Synthesis of rare-earth doped ZnO nanorods and their defect-dopant correlated enhanced visible-orange luminescence. RSC Adv 6(2), 35892–35900 (2016).

Heo, Y. W., Norton, D. P. & Pearton, S. J. Origin of green luminescence in ZnO thin film grown by molecular-beam epitaxy. J Appl. Phys 98, (2005).

Van Dijken, A., Meulenkamp, E. A., Vanmaekelbergh, D. & Meijerink, A. Identification of the transition responsible for the visible emission in ZnO using quantum size effects. J. Lumin. 90, 123–128 (2000).

Van Dijken, A., Makkinje, J. & Meijerink, A. The influence of particle size on the luminescence quantum efficiency of nanocrystalline ZnO particles. J. Lumin. 92, 323–328 (2001).

Potzger, K. et al. Ferromagnetic Gd-implanted ZnO single crystals. J Appl. Phys https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2183350 (2006).

Van Dijken, A., Meulenkamp, E. A., Vanmaekelbergh, D. & Meijerink, A. The kinetics of the radiative and nonradiative processes in nanocrystalline zno particles upon photoexcitation. J Phys. Chem. B 104, 1715–1723 (2000).

Sedky, A., Almohammedi, A., Afify, N. & Abbady, G. Negative dielectric constant and multi-visible photolumenses emissions of Cd(1-x)CoxO nanocomposites with (0.00 ≤ x ≤ 1.00). Inorg. Chem. Commun. 163, 112301 (2024).

Mehedi Hassan, M., Khan, W., Azam, A. & Naqvi, A. H. Influence of Cr incorporation on structural, dielectric and optical properties of ZnO nanoparticles. J Ind. Eng. Chem. 21, 283–291 (2015).

Zamiri, R. et al. Influence of Mg doping on dielectric and optical properties of ZnO nano-plates prepared by wet chemical method. Solid. State. Commun. 195, 74–79 (2014).

Musselman, K. P. et al. Improved exciton dissociation at semiconducting polymer:zno donor:acceptor interfaces via nitrogen doping of ZnO. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201303994 (2014).

El-Shaarawy, M. G., Khairy, M. & Mousa, M. A. Structural, electrical and electrochemical properties of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using dry and wet chemical methods. Adv. Powder Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.01.009 (2020).

Lanje, A. S., Sharma, S. J., Ningthoujam, R. S., Ahn, J. S. & Pode, R. B. Low temperature dielectric studies of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles prepared by precipitation method. Adv. Powder Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2012.08.005 (2013).

Eroǧlu, A., Tataroǧlu, A. & Altindal, Ş. On the temperature dependent dielectric properties, conductivity and resistivity of MIS structures at 1 MHz. Microelectron. Eng. 91, 154–158 (2012).

Samanta, A., Goswami, M. N. & Mahapatra, P. K. Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles as novel photonic and multiferroic semiconductor. Mater Chem. Phys. 240, 122180 (2020).

Singh, J., Virpal, Sharma, S. & Singh, R. C. Effect of Fe2O3 doping on structural properties of ZnO-V2O5 based varistor system.. AIP Conf. Proc. 1832, 120021 (2017).

Dongol, M., El-Nahass, M. M., El-Denglawey, A., Abuelwafa, A. A. & Soga, T. Alternating current characterization of nano-Pt(II) octaethylporphyrin (PtOEP) thin film as a new organic semiconductor. Chin. Phys. B. https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/25/6/067201 (2016).

Ram, M. & Negi, N. S. Effect of (Fe, Co) co-doping on the structural, electrical and magnetic properties of ZnO nanocrystals prepared by solution combustion method. Phys B Condens. Matter. 481, 185–191 (2016).

Cherifi, Y. et al. Electrical, dielectric and photocatalytic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanomaterials synthesized by Sol gel method. Process. Appl. Ceram. https://doi.org/10.2298/PAC1603125C (2016).

Molak, A. et al. Electric modulus approach to the analysis of electric relaxation in highly conducting (Na0.75Bi0.25)(Mn0.25Nb 0.75)O3 ceramics. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/38/9/019 (2005).

Kirouani, I. et al. Effect of the phosphonomethylene moiety on the structural, vibrational, energetic, thermodynamic and optical proprieties of ((Phenylcarbamoylmethyl-phosphonomethyl-amino)-methyl)-phosphonic acid: DFT investigation. J Mol. Struct. 1215, 128193 (2020).

Ramesh Babu, N. C. et al. Low temperature dielectric dispersion and electrical conductivity studies on Fe 2O 3 mixed lithium yttrium silicate glasses. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 358(23), 3175–3186 (2012).

Mahapatra, T., Halder, S., Bhuyan, S. & Choudhary, R. N. P. Dielectric and electrical characterization of lead-free complex electronic ceramic: (Bi1/2Li1/2)(Zn1/2W1/2)O3. J Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron 29, 18742–18750 (2018).

Nasrallah, D. A., El-Metwally, E. G. & Ismail, A. M. Structural, thermal, and dielectric properties of porous PVDF/Li4Ti5O12 nanocomposite membranes for high-power lithium-polymer batteries. Polym Adv. Technol. 32(3), 1214–1229 (2021).

Yuan, R., Dong, Y., Hou, R., Zhang, S. & Song, H. Review—influencing factors and suppressing strategies of the self-discharge for carbon electrode materials in supercapacitors. J Electrochem. Soc. 169(3), 030504 (2022).

Abd-Elrahim, A. G., Sedky, A., Afify, N. & Abbas, A. The effect of composition on the structure, optical, and room-temperature ferromagnetic properties of hydrothermally synthesized (ZnSn)1-xCuxO nanocomposites. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 674, 415568 (2024).

Amin, S. A. & Sedky, A. On the correlation between electrical, optical and magnetic properties of Zn1-xPrxO nanoparticles. Mater Res. Express 6, 065903 (2019).

Ateia, E. E., El-Bassuony, A. A., Abdelatif, G. & Soliman, F. S. Novelty characterization and enhancement of magnetic properties of Co and Cu nanoferrites. J Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 28(1), 241–249 (2017).

Sedky, A., Afify, N., Abbas, A. & Abd-Elrahim, G. Cooperative effects due to Zn–Sn replacement by Co-ions on the optical and magnetic properties of (ZnSn)1- xCoxO nanocomposites. Mater. Chem. Phys. 313, 128776 (2024).

Kamble, V. B., Bhat, S. V. & Umarji, A. M. Investigating thermal stability of structural defects and its effect on d0 ferromagnetism in undoped SnO2. J Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812382 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. Sub-nanometer thick wafer-size NiO films with room-temperature ferromagnetic behavior. Angew Chemie - Int. Ed https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202110185 (2021).

Theyvaraju, D., Muthukumaran, S. & Microstructure,. Crystallographic and photoluminescence examination of Ni Doped ZnO nanoparticles Co-doped with Co by Sol–Gel method. J Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 27(5), 1572–1582 (2017).

Sedky, A. & Ziq, K. A. Mechanical and magnetic properties of ZnO/Fe 2O 3 ceramic varistors. Superlattices. Microstruct. 52(1), 99–106 (2012).

Sedky, A., Ali, A. M., Sayed, M. A. & Almohammedi, A. On the dielectric and magnetic properties of Al doped Pr:123 for advanced devices: A comparison with ZnO. Results Phys. 52, 106834 (2023).

Almessiere, M. A., Slimani, Y. & Baykal, A. Structural and magnetic properties of Ce-doped strontium hexaferrite. Ceram Int 44(8), 9000–9008 (2018).

Trukhanov, A. V. et al. Impact of the nanocarbon on magnetic and electrodynamic properties of the ferrite/polymer composites.. Nanomaterials 12, 868 (2022).

Ouyang, J., Mu, D., Zhang, Y., Yang, H. & Suib, S. L. Selective fabrication of barium carbonate nanoparticles in the lumen of halloysite nanotubes. Minerals 8(7), 296 (2018).

Almessiere, M. A., Slimani, Y., Sayed, E. & Baykal, A. Structural and magnetic properties of Ce-Y substituted strontium nanohexaferrites. Ceram. Int. 44(11), 12511–12519 (2018).

Mosquera, E., Del Pozo, I. & Morel, M. Structure and red shift of optical band gap in CdO-ZnO nanocomposite synthesized by the sol gel method. J. Solid. State. Chem. 206, 265–271 (2013).

Khan, R. et al. Room temperature dilute magnetic semiconductor response in (Gd, Co) co-doped ZnO for efficient spintronics applications. RSC Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra06637h (2022).

Khan, R. et al. Influence of oxygen vacancies on the structural, dielectric, and magnetic properties of (Mn, Co) co-doped ZnO nanostructures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-018-9018-z (2018).

Khan, R. et al. Effect of Sn-doping on the structural, optical, dielectric and magnetic properties of ZnO nanoparticles for spintronics applications. J Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 32(16), 21631–21642 (2021).

Astuti, Arief, S., Muldarisnur, Z. & Usna, R. A. Synthesis and Properties of Magnetic-Luminescent Fe3O4@ZnO/C Nanocomposites.. J. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/2381623 (2023).

Almoneef, M. M. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of magnetic ZnO/Fe3O4 nanocomposites: Structural, morphological, antimicrobial, and anticancer evaluation. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices. 10, 100921 (2025).

Ahmed, A. A. A., Abdulwahab, A. M., Talib, Z. A., Salah, D. & Flaifel, M. H. Magnetic and optical properties of synthesized ZnO–ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites via calcined Zn–Fe layered double hydroxide. Opt Mater. (Amst) 108, 110179 (2020).

Yu, X. et al. Room temperature ferromagnetism and diamagnetism of Co-doped ZnO microspheres synthesized by sol-gel method. Mater. Lett. 122, 234–236 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU; grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Mansour Mohamed** contributed to the samples preparation, measurements, data analyzing, discussion, and writing the manuscript. **A. Sedky** contributed to the measurements, data analyzing, discussion and writing the paper. **Abdullah S. Alshammari** contributed to sample preparation, SEM measurements, data analyzing and revising the manuscript. **Emad K. Jaradat** contributed to discussion and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, M., Jaradat, E.K., Alshammari, A.S. et al. Enhanced optical, dielectric and ferromagnetic properties in ZnO/M nanocomposites for advanced device applications. Sci Rep 15, 40353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26399-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26399-x