Abstract

We studied a selection of single stranded (ss)RNA bacteriophages (Class Leviviricetes) in rumen samples from dairy cows. These phages are non-enveloped, positive sense bacteriophages infecting Gram-negative bacteria, e.g. Escherichia, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, or other Gammaproteobacteria. Leviviricetes phages have small genomes and are of interest, as they likely predate on commensal or pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria. These phages attach to retractile pili on the bacterial surface, characterising them as male- or sex/conjugation-dependent phages and may interfere with bacterial conjugation and antimicrobial resistance. We assembled 52 Leviviricetes sequence contigs with homology to reported Leviviricetes. Our findings indicate that the majority of these phage sequences are found in the rumen liquid rather than the solids fraction, that clearance rates are slow and consistent with rumen liquid clearance, and that abundance of individual phage contigs differ among cows and sampling times, consistent with dynamic bursts of replication and clearance. Some phage contigs were detected for up to 8 weeks, and considered part of a resident, dynamic virome, while other phage contigs become undetectable, suggesting transient infection. Our data may suggest a highly dynamic system, possibly caused by predator–prey interactions between a group of ssRNA bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts in the rumen of dairy cows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advanced abilities of ruminants to digest feed, are due to complex communities of microorganisms, including archaea, bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and viruses, present in the rumen, reticulum and omasum compartments of the ruminant stomach1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Here, recalcitrant plant components such as roughage and dietary fibers that are hard to digest, are microbiologically fermented into predominantly useful products such as volatile fatty acids8. These fermentation products and bacterial proteins are then a significant energy source for the animal. Thus, the commensal relationship between ruminants and their microbiome have co-evolved together and enabled the success of this group of animals9. Over the past decades, ruminal bacteria, archaea, protozoa, and, to a lesser extent, fungi have been extensively studied. However, ruminal viruses, i.e. mainly bacteriophages, have been mostly overlooked and only recently are gaining more attention for their potential effects on animal health and productivity. Despite virus-focused studies contributing to the characterisation of the rumen virome, our understanding of their function and host–virus interaction remains limited. Clearly, the rumen microbial composition affects the type and quantity of fermentation products and thus the efficiency of nutrient acquisition10. While known influences on community composition include diet, ruminant species and genetics, and e.g. geographical area, the role of viruses in shaping or maintaining the rumen microbiome is sparsely documented. However, there are some evidence, albeit mainly based on studies of DNA bacteriophages, that points to the presence of a highly diverse rumen virome that may play a role in maintaining rumen homeostasis and thus host health and productivity11. In particular likely obligate lytic phages, such as the abundant positive sense, single stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses in the Class Leviviricetes12, may be of interest, as they are likely to selectively predate on commensal, or possibly pathogenic Gram-negative host bacteria and thus contribute to the evolutionary adaptation of the local microbiome—which has been shown in other animals, including humans13, but is not yet proven in regards to the cow rumen.

Large numbers of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages or in short phages) have been found by metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analysis, and in particular, the amount of sequence information regarding bacteriophages having a single stranded (ss), positive sense RNA genome, so-called Narna-Levi-like viruses including the Class Leviviricetes, have recently been vastly expanded3,4,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. However, these studies are mainly based on analysis of wastewater or environmental samples, while little is known about these RNA phages in e.g. the rumen and whether such phages can or should be considered as resident or transient members of the local virome. Clearly, for the dairy cow rumen, the major focus of previous studies has primarily been on the characterisation of DNA viruses1,2,4,5,11, many of which are integrated into the host bacterial genome, leaving gaps in our knowledge of ssRNA bacteriophages, thought to be obligate lytic viruses.

The bacteriophages in the Class Leviviricetes are non-enveloped positive sense ssRNA viruses that are thought to infect and lyse various Gram-negative bacteria, e.g. Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, and other members of the bacterial Class Gammaproteobacteria. These viruses (phages) possess small genomes, typically ranging from 3000 to 5000 nucleotides, which generally encode four essential proteins: maturation protein (Mat), coat protein (CP), the β-subunit of the replicase (Rep), and a lysis protein (Lys). Mat and CP provide the structural proteins of the phage, while Rep is involved in replication of the virus genome within the host. Lys aids in bacterial lysis to release new virus particles. Positive sense ssRNA phages are classified as mainly lytic viruses and thought to follow a straightforward infection cycle that includes host attachment and adsorption, genome entry, genome replication, phage assembly, and the release of new virions through host cell lysis. Based on the few phages for which this has been studied, these phages attach to retractile pili on the bacterial surface, which characterises them as F- or male-specific, plasmid-specific, or sex/conjugation-dependent phages. This property makes them particularly interesting in terms of bacterial host range and conjugation, including the potential reduction in the transfer of certain antimicrobial resistance genes3,12,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Moreover, these phages do not require or produce a DNA intermediate and consequently, cannot integrate into the host genome, most likely making them obligate lytic viruses and excellent candidates for detection through metatranscriptome sequencing. Hence, we here focus on defining and semi-quantitating a selection of such ssRNA Leviviricetes bacteriophage sequences present in the rumen of dairy cattle. For our study described here, we analysed 88 metatranscriptome samples collected from 12 high-yielding dairy cows to identify ssRNA bacteriophages resident to the rumen environment32,33 and to study their potential dynamics. The majority of these phages appear to be part of the rumen liquid fraction as opposed to the solids parts and that clearance/passing rate of these phages in the rumen are relatively slow, i.e. consistent with the rates published for liquid fraction clearance in the rumen of cattle33,34,35,36,37. The amount/proportion of each individual phage contig may differ among cows and among sampling times, consistent with dynamic bursts of replication followed by reduction/clearance, while some of these phages could be detected in sequential samples separated by up to 8 weeks. Overall, our data may suggest an ongoing predator–prey dynamic38,39,40 between a large group of ssRNA bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts.

Materials and methods

Experiments

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experiments were approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Directorate under license no. 2018-15-0201-01495.

Animals and samples

Animal experiments were conducted at Aarhus University, AU Viborg—Research Centre Foulum, Denmark, under a license from the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (license no. 2018-15-0201-01495). The experiments were planned under consideration of the ARRIVE Guidelines and guidelines set out by the Danish Ministry of Environment and Food (act 474 of 15th of May 2014 and executive order 2028 of 14th of December 2020) concerning animal experimentation and care of animals under experiments.

The 88 samples used for this study consisted of rumen samples from dairy cows collected in two separate studies. The first study, Trial 1, was a feeding trial looking at the effect of the addition of red seaweed to the diet. The experiment was performed with 4 Danish Holstein cows and 4 dietary treatments in a 4 × 4 Latin square design41. Total rumen content was sampled directly through a rumen cannula once per period at 7:30 a.m. for a total of 16 samples (4 per animal) once a week for 4 weeks (days 8, 15, 22, and 28). Grab samples were taken from the dorsal, ventral, cranial, and caudal rumen, pooled, and mixed and immediately placed in liquid nitrogen for later storage at − 70 °C. Samples from these 4 cows were initially used to assemble contigs for selection of sequences representing single stranded RNA bacterial viruses (see further below).

The second feeding trial, Trial 2, consisted of 2 diets and 2 experimental periods of 22–28 days in a crossover design33. Samples (N = 72) were taken from 8 cows at day − 1 (before diet shift), day 22 (21 days after first diet shift), and day 50 (16–20 days after second diet shift). On the day before transitioning the cows to the experimental diets (d − 1) rumen samples (N = 24) were taken directly through the rumen cannula at 14.00 h from the dorsal, ventral, cranial, and caudal rumen, pooled, and mixed and total rumen content (total, N = 8) was subsampled. The remaining sample was then divided into liquid (liquid, N = 8) and solid (solid, N = 8) fraction by filtering through a nylon mesh liner (pore size 70 microns). Additionally, total rumen content samples were taken from the same 8 cows in week three after each diet shift (d22 and d50) at 06:00, 09:00 and 11:00 a.m. (N = 48). All samples were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for later storage at − 70 °C. For further details of the setup and samples from the trials see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2.

Metatranscriptomics

Rumen samples were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 70 °C. Nucleic acids were extracted from the samples in-house using the MN NucleoSpin RNA Stool kit (Macherey–Nagel, Düren, Germany; REF: 740130.50) followed by genomic DNA removal using a TURBO DNA-free™ Kit (InvitrogenTM, Catalog number: AM1907). Briefly, samples were ground while frozen using liquid nitrogen to avoid RNA degradation under defrosting, and 100 mg ground sample was weighed while frozen and placed in NucleoSpin Bead tube A added 150 µL NucleoZOL and 800 µL RTS1 buffer followed by bead beating with a Qiagen Tissue Lyser at full speed for 60 s. Final extracted RNA was eluted in 50 μL RNase free water and RNA concentration measured by Nanodrop before submission to a commercial supplier (BGI, Shenzhen, China) and sequenced after initial ribosomal RNA depletion. Metatranscriptomic sequencing was performed on a DNBSEQ™ sequencing platform (BGI, Shenzhen, China) providing approximately 24 mill paired-end reads (i.e. a total of 48 mill reads) of 150 nucleotides in length per sample after removal of adapters and removal of low-quality reads.

Sequence analysis

The paired-end reads were filtered and quality checked by the commercial vendor (removing adapters and low-quality reads, with a phred score at 33 or less) and received by us as fastq files. Received files were directly imported into the Qiagen CLC Workbench Premium software (version 24.0.2; QIAGEN, Aarhus, Denmark https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/) with a standard setting as Illumina paired-end reads. Initial quality checks included running the CLC “Trim Reads” tool with settings; Remove failed reads, Quality 0.05, ambiguity max 2, remove reads shorter than 100 and remove poly A from 3′-end and poly G from the 5′-end. This resulted in very few reads being filtered or trimmed, with only around 800–1000 reads (around 0.05%) being filtered away and average read length only being reduced from 150 to 149.93 (a reduction of only 0.05% in average length of the reads). This indicated that the reads were well filtered and trimmed as received from the vendor, and consequently, we used the received fastq files without further filtering or trimming. We also ran the fastq files against the bovine host genome (Bos taurus ARS-UCD1.3) using the CLC Taxonomic Profiling Tool at default settings to assess the amount of bovine host RNA present. The amount of host reads in these samples were consistently less than 0.05% of the total reads, and consequently, we did not filter or normalise abundances regarding bovine host RNA. Similarly, we did not normalise the number of reads mapped in relation to total reads analysed, because total read numbers and read length were very consistent for all samples (see Supplementary Table 1 for details), with 84 of the 88 samples having 24 million paired reads (total 48 mill reads) while the other 4 samples varied between 21.42 and 25.21 million paired reads (42.84–50.42 total reads and thus a variability within a factor of 0.9–1.05). Given this minimal variation, we consider the risk of bias due to differences in sequencing depth negligible. Consequently, we here consistently show abundances as number of reads mapped in a given sample (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Initial checks of read count distributions and Spearman rank correlation among phage abundances were done in Excel (version 2410; Build 18129.20158) and GraphPad Prism (version 10.3.1 for Windows; GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA, www.graphpad.com), while the major statistical analyses of phage read counts were conducted in R (version 4.3.2)42 using RStudio (version 2021.09.0.351)43. For Trial 1, a single dataset was generated to investigate whether phage composition varied across sampling times 1 week apart (Timeseries 1A, containing the number of phage contigs detected per cow in samples collected weekly alongside dietary information). For Trial 2, three datasets were established to assess whether phage composition differed (1) between sample types (Baseline dataset: samples collected on day − 1 from total rumen fluid, its liquid fraction, and its solid fraction, N = 24), (2) across sampling days 3–4 weeks apart (Timeseries 2A dataset: total rumen fluid samples collected at 14:00 on day − 1 and at 11:00 on days 22 and 50, N = 24), and (3) within a single day across different sampling times within a 5-h window (Timeseries 2B dataset: total rumen content samples collected at 06:00, 09:00, and 11:00 on days 22 and 50, N = 48).

Trial 1 and Trial 2 data were analysed in a comparable manner. For each dataset, phage contigs with zero variance were removed. Zero variance contigs were defined as contigs with no mapped reads resulting from data subsetting. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted for each dataset independently using singular value decomposition on centered, log-transformed phage counts scaled to unit variance, using the prcomp function from the stats package (R base). PCA scores were extracted and visualized in ordination plots generated using the ggplot2 package (version 3.4.4)44. Statistical comparisons were conducted based on Euclidean distances between PCA scores, which were assessed by Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) with 9999 permutations using the adonis2 function in the vegan package (version 2.6-4)45. Pairwise group comparisons were conducted using the pairwiseAdonis package (version 0.4.1)46, also applying 9999 permutations. Homogeneity of multivariate dispersions was evaluated with the betadisper function implemented in vegan and confirmed for all variables in the Trial 1 dataset (Timeseries 1A) and for all but one variable in the Trial 2 datasets (CowID Timeseries 2A: P = 0.01, CowID Timeseries 2B: P = 0.02, CowID Baseline: P = 0.01). As PERMANOVA is considered less sensitive to dispersion effects compared with alternative approaches, the observed violations for CowID were accepted44,47.

To assess differences in Sample Type in the Baseline dataset, PERMANOVA was employed with Sample Type (total, liquid, solid) as the main factor and using CowID as a stratum to restrict permutations within cows. Temporal changes in phage composition were assessed separately for data collected within a 5-h window (Trial 2, Timeseries 2B), weekly (Trial 1, Timeseries 1A), and 3–4 weeks apart (Trial 2, Timeseries 2A) using PERMANOVA. For all models, marginal effects of explanatory variables were tested (the “by” argument was set to “margin”), and permutations were restricted within cows to account for repeated measures. In the Timeseries 2B dataset (short-term variation), an additive model was applied including Sampling Time (06:00, 09:00, and 11:00), Experimental Day (d22 and d50), and Diet (diet 1: low roughage, diet 2: high roughage). In the Timeseries 1A dataset (intermediate-term variation), Experimental Day (d8, d15, d22, d29) and Diet (Con, Low, Med, High) were tested as additive explanatory variables. In the Timeseries 2A dataset (long-term variation), PERMANOVA was conducted with Experimental Day (d-1, d22, and d50) and Diet (base diet, diet 1, diet 2) as additive explanatory variables. Interaction terms were initially included in all models but removed due to lack of significance. Finally, cow-specific effects on ssRNA phage composition were assessed individually and for each dataset separately by performing PERMANOVA with CowID as the main factor.

Looking for potential bacterial hosts for detected ssRNA phages

The bacterial hosts for the selected ssRNA phages (contigs) are likely to be Gram-negative Gammaproteobacteria such as e.g. Escherichia, Salmonella, Pseudomonas or other Enterobacterales. Consequently, we estimated the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria detected in each sample using the “Taxonomic Profiling” function in CLC, based on both paired reads and assembled contigs, against the curated microbiological database (QMI Family) available in CLC. It should be noted that bacterial taxonomy usually is inferred from DNA sequences rather than RNA as done here. Although, these estimates are not directly comparable to the DNA-based microbiome profiles, they provide a reasonable indication of the relative abundance of transcriptionally active Gammaproteobacteria detectable in the RNA data.

Results

Assembling and selection of contigs

The first step in the analysis of the samples included in this study, included merging and selecting overlapping paired reads (that is paired-end reads with an overlap of at least 8 nucleotides allowing assembly into single, longer reads to increase final contig assembly accuracy) to use for initial mapping and assembling of contigs from individual samples, that were assembled using the De Novo Assemble Metagenome tool available in the CLC software and a setting of Longer Contigs (iterated word size of 21, 41 and 61), an initial minimum contig length of 700 nucleotides and with the Perform Scaffolding option selected. All merged reads from the sixteen samples from the 4 cows in Trial 1 were then compared by using BlastN to a selection of 23 available NCBI sequences (KF615862-69; KF616858-62; AB218927-32; LC710217-19; KF510034) from single-stranded RNA bacteriophages available on NCBI. We chose not to conduct a wider search based on similarity to RdRP of RNA viruses as we have found many entries that were not based on the positive strand or with uncertain classification. Consequently, we chose a strategy with a more narrow starting search, with a high degree of certainty to the quality of the sequence. These NCBI sequences were selected so that contigs selected by us would have a very high certainty of being from genuine RNA bacteriophages from where we could further expand our search and selection. This resulted in a single sample (Cow 4, sample LabID B12, Supplementary Table 1) having more than 100 reads matching to one of the NCBI sequences (KF616862, Reference—https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26112785/), while another 3 samples, all from the same cow as sample 12 (i.e. Cow 4, samples LabIDs B20, B28 and B36), had a few reads that matched this reference. Subsequently, all assembled contigs from the sixteen samples from Trial 1 were compared to the selected NCBI references using tBlastX and BlastN with a setting requiring the E-value being less than 10e−16 or less than 10e−5, respectively, and the detected “High-scoring Segment Pairs (HSPs)” greater than 100, the bit score above 46, and the greatest identity or positive percent above 75. Contigs fulfilling these criteria were carefully inspected, and for the sixteen Trial 1 samples, we selected 12 contigs of which 10 were retained (i.e. not later replaced by another contig being identical/near identical but longer) in the final selection (see below). We then followed the same process, albeit assembling contigs from all reads (and thus not only merged reads) in the samples and comparing contigs to both the NCBI references as well as to the already selected contigs from Trial 1 (mentioned above) for the assembled contigs from the first 36 samples (4 of 8 cows) from Trial 2, which resulted in initial selection of 25 contigs of which 19 were retained (i.e. not later replaced by another contig being identical/near identical but longer) in the final selection together with the 10 contigs mentioned above for a total of 29 contigs selected from a total of 22 of the 52 samples from the included 8 cows. Subsequently, we followed the same process for contigs assembled from the additional 36 samples from 4 cows from the Trial 2, which resulted in initial selection of an additional 63 contigs of which some replaced shorter contigs already included, resulting in a final list of 52 contigs encoding for ssRNA phages selected from the included samples from a total of 12 cows. This list of 52 ssRNA contigs (fasta file provided as Supplementary Data 1) was then checked by running BlastX against virus proteins in the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database (National Library of Medicine (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)—(All non-redundant GenBank CDS translations + PDB + SwissProt + PIR + PRF excluding environmental samples from WGS projects; Molecule Type: Protein; Update date:2024/10/16; Number of sequences: 822567496)48) to ensure that all 52 contigs had protein homology to known RNA polymerase, coat or maturation proteins of the single-stranded RNA viruses of the virus Class Leviviricetes12. As this group of viruses have a positive sense RNA genome, all contigs are shown as positive sense, by reverse complementing any contigs being negative strand. Finally, read mappings were checked visually, in CLC and for the initial contigs selected, in IGV (Integrated Genomics Viewer version 2.17.449,50. The final 52 selected contigs/ssRNA virus sequences (see Supplementary Data 1) were 2195–5001 nucleotides in length with a mean and median length of 4133 and 4212 nucleotides, respectively.

Quantitation of reads in each sample mapping to individual contigs/ssRNA viruses

Mapping reads to contigs was done by using the CLC “map sequences to references” using all reads for each sample, the 52 ssRNA virus contigs as references, and the following setting: Match score = 1; Mismatch cost = 2; Cost of insertions and deletions = Linear gap cost; Insertion cost = 3; Deletion cost = 3; Length fraction = 0.5; Similarity fraction = 0.8; a Minimum seed length = 15; and the setting for non-specific match handling to random. These setting were chosen to include reads from related sequences, i.e. that were likely to be from the same species. The mapping file was visually checked in CLC integrated genomics viewer to ensure reads mapping to contigs did in fact represent reads with a closely related sequence. To further check for the possibility of unrelated reads mapping to a contig, read mapping with more stringent criteria of read length above 0.95 was checked on a subset of the samples and this resulted in minimal changes of < 1% fewer reads being mapped. Evenness of the mapped reads was assessed from visual inspection of the contigs, and the reads were distributed along the contig and were found at levels of a minimum of around 200 reads, but in general > 1000 reads for most of the contigs. The total number of reads mapping to each contig was recorded. The quantity is recorded simply as number of reads without any normalisation as described above, as the total number of reads per sample is around 48 mill (42.84–50.42 mill total reads, i.e. within a factor of 0.9–1.05) and the length of the contigs differ less than 2.5-fold and thus any adjustment would only have minor or no impact on the results as presented. Furthermore, non-specific matches, i.e. reads mapped to more than a single contig, constituted a very low percentage of reads in the order of 0–1% of mapped reads and consequently, considered to have no significant or major effect on read counts. For statistical analysis and visualisation of the data using the logarithmic scale for read counts, we added “1 read” to all bins with 0 (zero) reads recorded (Supplementary Table 1).

ssRNA phage differences between different rumen fractions

Statistically significant differences in ssRNA phage composition were observed between rumen fractions (total sample, solid fraction, liquid fraction) at baseline (d − 1), when cows were maintained on the same diet (P = 0.002, Table 1A; Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the effect size was small, with only 2.6% of the total variation in phage composition explained by Sample Type (R2 = 0.026, Table 1A ). While the estimated abundances of the 52 ssRNA phage contigs (Supplementary Table 1) were generally similar across fractions, the liquid fraction consistently showed higher read counts compared to the total sample and solid fraction, whereas the solid fraction tended to be lower. Summed across all 52 phage contigs in the relevant samples, the liquid fraction contained on average 1.64-fold more reads than the total sample, whereas the solid fraction contained only 0.76-fold the reads of the total sample. This may not be surprising, as removing coarse material from the total sample to obtain the liquid fraction may also remove feed-associated RNA (e.g., plant, bacterial, and other non-viral RNA), thereby enriching the relative proportion of viral reads. As all samples contained approximately 48 mill reads, cleaner fractions may indirectly give higher relative phage contig abundances. Nevertheless, these differences remained within a twofold range of the total sample, whereas detected variation in phage contig abundances across time exceeded this (see below). Thus, the total sample was considered suitable for downstream analyses. The results further indicate, that only a minority of the detected ssRNA phage contigs are associated with the coarse rumen contents. Based on the estimated abundances, the relative ratios between total, solid, and liquid fractions imply that approximately 72% of the total sample volume corresponds to the solid phase and approximately 28% to the liquid phase. Although not directly measured on these samples, these estimates closely align with independent reports of total rumen content under similar conditions, where the solid fraction typically represented 72–77% of the volume33. This suggests that the modest differences in contig abundances between fractions are more likely explained by higher ssRNA phage loads in the liquid fraction, rather than by indirect enrichment due to removal of feed-associated RNA alone.

ssRNA phage dynamics in the rumen over time

For subsequent abundance data comparisons, we used the total samples, see details for all samples from the 4 cows in Trial 1 and from the 8 cows from Trial 2 (Supplementary Table 1).

Patterns observed within a day

To assess whether mapped ssRNA phage reads reflected introduction through feed or active viral replication in the rumen, we compared samples from 8 cows in Trial 2 (Timeseries 2B dataset) that were collected at 06:00 (before morning feeding), 09:00 (about 2 h and 45 min after feeding), and 11:00 (i.e. about 5 h after feeding) at d22 and d50. The number of mapped reads for the 52 ssRNA phage contigs was highly similar between timepoints within cows, and no significant differences in overall phage composition were detected across the 5-h sampling period (P = 0.99, R2 = 0.003, Table 1A Timeseries 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4). Instead, variation in phage composition was explained by Experimental Day (P = 0.0001, R2 = 0.116, Table 1B Timeseries 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4A), Diet (P = 0.0001, R2 = 0.135, Table 1B Timeseries 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4B), and CowID (P = 0.0001, R2 = 0.418, Table 1B Timeseries 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4C). Total mapped read numbers were slightly higher before feeding (06:00) compared to later timepoints, with ratios of 0.79 at 09:00 and 0.82 at 11:00 relative to pre-feeding levels. The observed minor decrease after feeding, rather than an expected increase if phages were introduced with feed, suggests that these phages replicate in the rumen. The slight reduction observed likely reflects a dilution effect, where feed-derived RNA temporary lowers the relative proportion of viral reads. Together, these results indicate that the ssRNA phage contigs are part of the resident ruminal virome and that their composition remains stable over short time scales (at least 5 h), suggesting that ssRNA phage kinetics in the rumen may be slow. Given the apparent short-term stability, we next examined ssRNA phage abundance and composition over longer periods.

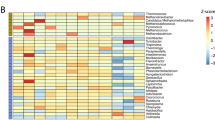

Patterns observed over weeks

To further examine whether the detected phage contigs are part of the resident ruminal virome, we assessed whether phage contigs remained detectable over longer time scales or were cleared. In Trial 1, samples from the same cows (N = 4) were collected at 4 timepoints, 1 week apart (days 8, 15, 22, 29), while in Trial 2, samples were repeatedly collected from 8 cows (N = 24) at three timepoints, 3–4 weeks apart (days − 1, 22, 50). Overall, phage contig abundances fluctuated substantially over time with phage contigs detected repeatedly within cows, further supporting that the detected ssRNA phage contigs are part of the resident ruminal virome (Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Table 1).

Figure showing the phage read counts for the 8 individual cows in Trial 2. The Y-axis is log10 scale and maximum set at 10,000 (104) reads. The day oftaking the samples is indicated on the X-axis and samples taken in Trial 2 are separated by approximately 3 weeks, with the first sample taken one dayprior the first diet shift (d-1), the second sample taken 3 weeks after the first diet shift (d22) and the third sample taken approximately 3 weeks after thesecond diet shift (d50).

In Trial 1, comparison of phage community compositions within cows revealed significant differences over time (P = 0.0007), with 19.9% of the total variation explained by Experimental Day (Table 1B; Supplementary Fig. S5A). Phage contig compositions did not differ between Diets (P = 0.37, 14.6% of total variation, Table 1A; Supplementary Fig. S5B) and no statistical interaction between Experimental Day and Diet was detected. Notably, 18 of the 36 phage contigs detected, were repeatedly observed within the same cow at abundances exceeding 100 reads for periods up to 4 weeks (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1). The number of detected phage contigs per cow ranged from 16 to 26 contigs with 13 shared at day 8, 19–22 contigs with 12 shared at day 15, 19–23 contigs with 13 shared at day 22, and 19–22 contigs with 12 shared at day 29 (Supplementary Figs. S6A and S7A). Overall, 8 phage contigs (101T-2563, 150T-1341, 31T-889, 94T-476, 196-333, 76-1072, 191-1758, 196-598) were consistently detected in all 4 cows at all sampling times.

In Trial 2, comparison of phage community compositions within cows revealed significant differences over time (P = 0.004, Table 1A, Timeseries 2A), with 8.8% of the total variation explained by Experimental Day (Table 1B Timeseries 2A; Supplementary Fig. S8A). In total, 51 phage contigs were detected, but abundances were generally lower compared to Trial 1 (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 2). The number of detected phage contigs per cow ranged from 12 to 27 different contigs with 1 shared across cows at day − 1, 15–37 contigs with 2 shared at day 22, and 10–24 contigs with 3 shared at day 50 (Supplementary Figs. S6B and S7B). Only phage contig 196–598 was consistently detected in all 8 cows at all sampling times. Although many of the phage contigs were detected repeatedly within the same cow, only 12 were observed more than twice within the same cow at abundances exceeding 100 reads, and just five of these were detected in more than one cow exceeding 100 reads (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 2). The lower number of phage contigs observed repeatedly at high abundances may reflect the longer intervals between sampling and the possibility of missing peak replication bursts.

The pattern and fluctuation of individual ssRNA phage contigs may differ among cows

Comparison of phage community compositions differed statistically between cows in Trial 1 (P = 0.003, CowID explaining 45.5% of the total variation; Table 1A Timeseries 1A; Supplementary Fig. S5C) but not in Trial 2 (P = 0.333, CowID explaining 31.3% of the total variation; Table 1B Timeseries 2A; Supplementary Fig. S8B). Furthermore, fluctuations of individual phage contigs were not necessarily synchronous and differed from phage contig to phage contig (Figs. 1 and 2). The rate of accumulation or removal of these phage contigs in the rumen is difficult to estimate from these data, but overall, peak levels appear to diminish by about 20–30-fold over a 3–4 week period. Similarly, but more difficult to assess from our results, increases in abundance likely occur at similar magnitudes (~ 20–30-fold) over the same time scale. However, some of these phage contigs may undergo several growth cycles within the 1–4 week sampling intervals, and indeed, some of these phages appear to accumulate much faster than the estimated 30-fold, with rates of increase or reduction ranging from 75- to more than 1000-fold over the 1 week or 3–4 week intervals studied (see Supplementary Dataset 2). It should be mentioned that any assessments of kinetics in these cases are complicated by the fact that the detected levels of these phage contigs may fluctuate from essentially undetectable (indicated by a value of 1 in Supplementary Table 1) to peak levels of up to 100,000 reads mapped to a single phage contig.

ssRNA phage dynamics in the rumen in response to dietary changes

In both Trial 2 datasets investigated for changes over time (hours: Timeseries 2B, weeks: Timeseries 2A), Diet explained part of the variation in phage contig composition. For within-cow comparisons of samples collected hours apart, Diet explained 13.5% of the total variation (P = 0.0001, R2 = 0.135, Table 1B Timeseries 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4B). For samples collected 3–4 weeks apart, Diet explained 10.3% of the total variation in within-cow phage contig composition (P = 0.0001, R2 = 0.103, Table 1B Timeseries 2A; Supplementary Fig. S8C). Interactions between Sampling Time and Diet or Experimental Day and Diet were not detected.

Additionally, a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was applied to the average number of phage reads in the 8 cows when fed high (diet 2) as compared to low roughage (diet 1). Although individual read counts do not perfectly follow a normal distribution, the average of the read counts per sample appear to follow a normal distribution. The two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed statistically significant differences between diets (P = 0.008), with more ssRNA phage reads observed in the high roughage samples. This suggests that diet 2 (high roughage) may provide an environment more favorable for ssRNA phages, potentially reflecting effects on their host bacteria (see subsequent text related to potential host bacteria), considering that it is the liquid fraction and not the solid fraction of the rumen content that contains the main load of these phage contigs. In contrast, no statistically significant effects of Diet on phage contig composition were observed in Trial 1, where cows were fed varying concentrations of seaweed in the diet (P = 0.3719, R2 = 0.146, Table 1A).

General positive and negative correlation among samples and phage contigs

To assess potential correlations among our data, we performed Spearman rank correlation analyses on the phage mapping results, looking separately at each Trial 1 and 2, at Trial 1 and 2 combined, as well as for a subset of phage results. The overall results, presented in Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10, indicate that while the data can generally be considered as independent measurements, there are combinations of samples and/or phage contigs that have a significant positive or negative rank correlation.

Assessing relatedness of these phage contigs and their potential host range

Comparing our 52 phage contigs to recently published virus sequences

To characterise our phage sequences “in silico” we compared the obtained sequences to virus sequences becoming available in recent publications using metatranscriptomics to define thousands of viruses, including bacteriophages12,14,17. First, we compared our 52 phage contigs to a downloaded database with more than 65,000 contigs representing Leviviricetes published by Neri et al., in 202217. Using BlastN and comparing our 52 selected phage contigs to that large database, indicate that all 52 of our contigs have some short stretches of similarity to one or more of these 65,000 Leviviricetes sequences, and looking at how well they match, it appears that 12 out of our 52 ssRNA phage contigs, albeit not being identical to any of these Leviviricetes, has similarity over more than 1000 nucleotides, the closest ones being 68–97% identical to one or more sequence in the database. The other around 40 contigs detected here, are also related to one or more sequences in the database, but only for short stretches of the genome and/or at a low percentage of identity (Supplementary Dataset 3 ). Regarding taxonomy, we checked 5 of our contigs with the highest similarity to sequences in this Neri et al.17 database, with an identity from 68 to 97% to sequences in the database, and it appears that we have both Order Timlovirales, Families Steitzviridae, and Blumesviridae; and Order Norzivirales, Family Fiersviridae. These viruses are not yet classified at the Genus or Species level, but would all be in the Phylum Lenarviricota, Class Leviviricetes12,17.

Secondly, another large study has recently been published by Hou et al. in late 202414, that has looked at more than 10,000 metatranscriptomics datasets with a huge amount of RNA virus sequences14 including many of relevance for the phage contigs selected by us for the rumen studies described here. The Hou et al.14 authors share a database/file with what they consider representative RNA virus species that contains around 162,000 virus species including around 58,000 species for the Narna-Levi-like viruses, i.e. single stranded, positive sense RNA viruses14. Using BlastN to compare our 52 selected rumen phage contigs against this the Hou et al.14 database (162,000 virus species) show that our 52 phage contigs have some similarity to the Narna-Levi-like viruses reported, although most of our phage contigs are quite distantly related. We selected three of our phage contigs that are closer related to one or more virus species in the Hou et al.14 database, with two out of the three of our contigs showing the closest relationship to one of their species, coming from biogas fermenter samples while the third one is from wastewater. However, the closest related phage contig we have to any of their virus species, our phage 27–1353, is 96% identical over 2700 nucleotides, and our full contig is 3506 nucleotides in length, so about 800 nt of our phage sequence is much more different and not closely related to anything they have listed. Our other phage contigs are much less related to any of their virus species or only related over a short part of the genome (Supplementary Dataset 4).

Phylogenetic comparison/Tree of the 52 selected ssRNA phage contigs

For phylogenetic comparison we initially aligned our sequences using the standard CLC alignment tool with default settings, followed by a more thorough alignment using ClustalW (version 3.0, available in the CLC Workbench). We then sequentially included the initial NCBI sequence KF616862.2 used to detect our first contigs as well as NC_073943, the sequence of an RNA bacteriophage designated AVE019 identified from activated effluent in the USA and identified as a relatively closely related sequence/bacteriophage. Finally, we included selected sequences from the relevant Neri et al.17 and Hou et al.14 databases that had a Blast e-value below 10e-12 and a greatest bit score above 80 when compared to our 52 contigs. This gave another 18 and 10 sequences included, for a total of 82 sequences in the alignment and phylogenetic analysis by Maximum Likelihood Phylogeny using the best fitting model (General time-reversible with Gamma and topology movement (GTR-GT substitution model) with 300 bootstraps as shown in Fig. 3. This phylogenetic comparison suggests that our newly described 52 bacteriophage contigs may fall in 8–12 different clusters and with 34 of them somewhat related to sequences already described by others14,17 or for an additional 7 contigs, being relatively close related to AVE019, a Bacterial Virus Reference sequence by NCBI (NC_073943). The last 11 of our bacteriophage contigs did not cluster with any of these previously described bacteriophages and for the total 41 contigs that did cluster, although they were somewhat related, we did see considerable differences, i.e. differences of 3–40% or more between our new sequences and any previously described bacteriophage sequence.

Phylogenetic Tree of the 52 selected ssRNA phage contigs Although direct comparison/alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the selected 52 phage contigs is somewhat difficult and may be inaccurate due to the high degree of variability, indels and known capacity for recombination, we attempted to align our sequences by initially generating a simple alignment using the standard CLC alignment tool with default settings, followed by a more thorough alignment using ClustalW Version 3.0 (available in the CLC Workbench). We then included the initial NCBI sequence KF616862.2 used to detect our first contigs as well as NC_073943, the sequence of an RNA bacteriophage designated AVE019 identified from activated effluent in the USA. Finally, we included sequences from the relevant Neri et al.17 and Hou et al.14 databases that had a Blast e-value below 10e−12 when compared to our 52 contigs. This gave another 18 and 10 sequences included, for a total of 82 sequences in the alignment and phylogenetic analysis followed by a Maximum Likelihood Phylogentic Tree using the best fitting model (General time-reversible with Gamma and topology movement (GTR-GT substitution model) with Gamma distribution and 300 bootstraps. Numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap values and only bootstrap values at or above 50% are shown. Clusters of contigs with an indicated relatedness to sequences reported by Neri et al.17 and to Hou et al.14 are indicated with a blue vertical line and ND or/and SP indicated, respectively. The tree is unrooted and the most diverse branch shown with a black vertical line and SP. and ND indicated towards the right bottom part of the Figure just below a branch containing 7 of our contig sequences being relatively closely related to the sequence of phage AVE019 (NC_073943).

Bacterial hosts for these phages

The exact hosts for these selected new 52 ssRNA phage contigs are not known but assumed to be within the bacterial Class Gammaproteobacteria such as e.g. E. coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas or other Enterobacterales. Although each phage may individually have a rather narrow host range, the many different species of this Class of viruses (Leviviricetes), may in combination infect many different bacteria, although most likely bacteria of the Class Gammaproteobacteria. The percentages of Gammaproteobacteria estimated from mapping of RNA and based on all reads or on assembled contigs are shown in Supplementary Fig. S11.

One can discuss bacterial abundance, as the actual percentages will vary depending on methods and what databases are used. Nevertheless, a large study7 concluded that Proteobacteria are the third most abundant phylum in the rumen, reticulum, and omasum of cattle, accounting for about 4% of the bacterial community, with Gammaproteobacteria representing roughly 30% of this fraction. This corresponds to an abundance of 1–1.5% of the bacterial community in the rumen, which still is substantial considering that there may be 10e10–12 bacteria per ml in the rumen. Our mapping in CLC indicated somewhat higher proportions of Gammaproteobacteria, particularly when based on read mapping compared to contig mapping (Supplementary Fig. S11 A,B). Furthermore, the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria appeared consistently higher in Trial 2 than in Trial 1, with estimates of 1–3% (reads) and 3–8% (contigs) in Trial 1 compared to 1–20% (reads) and 5–30% (contigs) in Trial 2. These values may be overestimated, possibly due to a combination of better representation of these bacteria in the reference database used and potentially higher transcriptional activity compared to other bacteria in the samples. However, we still believe that our values are comparable between samples analysed in the same way.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, similar to the phage contigs, Gammaproteobacteria reads also appear to be slightly more abundant in the liquid fraction as compared to the solid fraction and the total samples. This is based on samples from the 8 cows in Trial 2 that were split into 3 fractions, with average Gammaproteobacteria proportions of 13.43% (SD 3.85) in total sample, 10.26% (SD 4.39) in the solid fraction, and 22.63% (SD 4.69) in the liquid fraction. This again fits with the fact that we find around double as many phage reads in the liquid fraction as in the solid fraction while the total sample as expected is in between. Interestingly, the higher abundance of Gammaproteobacteria in the liquid fraction is not explained by a higher number of bacterial reads overall. In contrast, liquid fraction samples had on average only around 90% as many bacterial reads mapped as the solid fraction samples. This indicates that both ssRNA phage contigs and their presumed Gammaproteobacteria hosts are either more abundant or alternatively more transcriptionally active in the rumen liquid rather than in the rumen solid fraction. Furthermore, as for the phage data, comparison of Gammaproteobacteria abundance in the cows when fed diet 2 (high roughage) as compared to diet 1 (low roughage), results from the Wilcoxon signed rank test indicated a P value of 0.008. We interpret this as an indication that diet 2 (high roughage) may create an environment promoting increased growth or transcriptional activity of Gammaproteobacteria and consequently also their ssRNA phages in the liquid fraction of the rumen contents. However, we did not observe an obvious and direct correlation between abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and the sum of phage reads detected in the same sample. This may suggest that the connection between phage abundance and proportion of assumed target bacteria may be complex, or that things may be averaging out when looking broadly at a whole Class of bacteria and a broad selection of what likely are as many as 50 different Species of Leviviricetes phages. Nevertheless, we did observe a potential positive correlation between abundance and total phage contig reads (Supplementary Fig. S11A,C,D).

Discussion

We here present our results regarding temporal findings of an assembly of 52 curated Leviviricetes phage contigs in rumen samples from a total of 88 samples from 12 cows. We focus on detection and enumeration of RNA reads mapping to these relatively large (around 3–5 kb) RNA sequence contigs, that when translated to proteins, exhibited homology to characteristic proteins of the Class Leviviricetes, i.e. the RNA polymerase and in most cases also the maturation and capsid proteins and with the presence of additional open reading frames (ORFs, depicted in Supplementary Fig. S12), consistent with the presence of e.g. a lysis protein. The abundances of reads from the included metatranscriptomic samples mapped to the selected 52 ssRNA phage contigs, indicate that (A) the majority of these phages are part of the rumen liquid fraction as opposed to the solids parts, (B) that clearance/retention of these phages in the rumen are relatively slow, i.e. consistent with the times published for liquid fraction clearance in the rumen of cattle33,34,35,36,37, (C) that the amount/proportion of each individual phage may differ among cows and among sampling times, consistent with bursts of replication followed by reduction/clearance. Interestingly, our data indicate that overall abundance of these phages may be increased in cows fed a high roughage diet as compared to a low roughage diet, possibly linked to an increased abundance of Gammaproteobacteria, the assumed host for these bacteriophages, in the liquid fraction of the rumen. Remarkably stable read counts were observed in rumen samples collected over 5 h including samples taken before and after feeding implying the response to feed intake is not immediate which can be used to guide future studies in regards to appropriate sampling times.

Overall, our data suggest ongoing interactions between a large group of ssRNA bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts. Not much is known about the in vivo biology of these phages, as most studies have used metatranscriptomic data mining to characterise sequences, or in case of older studies, have focused on characterising a few of these phages in vitro3,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. However, based on what is known from the studies cited, is that the host for Leviviricetes phages most likely infect Gram-negative bacteria in the Class Gammaproteobacteria, with about 250 genera including highly important Genera such as Escherichia, Salmonella and Pseudomonas. Speculating on the abundance and potential role of the detected ssRNA phage contigs described here, the results show that several of these phage contigs have peak read levels at 10e4 or up to almost 10e5 reads among the roughly 48 mill reads analysed per sample. This may initially sound low, corresponding to 0.02–0.2% of all reads, however considering that these phages have genomes of only 2–5 kb, and consequently have full genome coverage from relatively few reads (say minimum 25–50 reads), a simplified comparison to their bacterial hosts, likely having a genome around 10e3 larger, suggests that bacteria may require roughly 10e3 more reads to fully cover a bacterial genome. Clearly, in this context it is important to realise that these results have been acquired using metatranscriptomic sequencing, and consequently, bacterial content of (m)RNA may not represent the full genome. However, based on recent findings by others, it does not appear to be unreasonable to use this factor of 10e3 for comparison of abundance between our Leviviricetes phages and their host bacteria51,52.

Under this set of assumptions, and assuming that most of the reads in these samples derive from bacterial RNA (as well as Archaeal and Eukaryotic RNA including a very low amount of bovine RNA as indicated in results), applying this factor would then indicate that each of the abundant phage contigs, may be present in numbers that are 0.2–2 times higher than the total number of bacteria detected in the sample. Furthermore, with an estimate of less than 10–15% of these bacteria being Gammaproteobacteria, this would indicate a ratio of up to 1–20 phages or more per potential bacterial host. Clearly many of these phages will have a much more limited host range, and consequently, it is not unreasonable to assume that the ratio of phage to host bacteria may be much higher, as may be indicated from in vitro studies30.

The kinetics of infection and replication of these phages in their bacterial hosts under the conditions found in the rumen of dairy cattle may be difficult to assess, but our data suggest that the level of individual phages differ over time and from cow to cow at any given time. Clearance, i.e. assessed on measurements of high going to low abundance, appeared to be consistent with established rumen liquid phase passing rate, for example as estimated by Kjeldsen et al.33, around 20% per hour. Assuming that assembled Leviviricetes virions are stable in the environment and assuming a complete stop of virus replication at a point when peak levels are reached, one would expect clearance of around 20% for the first hour, about 50% for 3 h and about 99% (10e2 reduction) by 24 h. This is of course assuming complete stop of virus replication after peak levels and emphasising that a given high abundance sample is not necessarily taken at peak levels, only at a time where abundance was high and potentially still increasing.

In regard to replication kinetics of these phages under the conditions found in the rumen of dairy cattle we do not have much information. However, based on what is known from somewhat related phages grown in vitro, it appears that the host bacteria likely are Gammaproteobacteria and that these types of phages prefer cells (bacteria) in exponential growth at above 30 °C and, at least in vitro, grown with aeration30. Under such conditions, such phages may infect and replicate to high levels within 75–120 min depending on starting phage concentration, although the actual lysis of host bacteria may take somewhat longer. Electron microscopy and cell culture studies have indicated that more than 4000 new virus particles are produced by a single infected bacteria, but that many of these virions stay associated with the infected bacteria while only 5% or less may bind to new target bacteria30.

It is currently not possible to state how infection may progress in the rumen bacteria of these dairy cows, first of all it is likely that growth conditions for the host bacteria will be anaerobic and thus not aerated, although we may assume that the temperature and growth conditions there will be suitable for exponential growth of suitable host bacteria. For example, bacteria in the Order Enterobacterales, of the Class Gammaproteobacteria, are facultative anaerobic, and thus potentially able to grow exponentially in the anaerobic rumen environment. In any event, clearly our results on temporal abundance of these phages in individual cows are consistent with burst of infection and replication although actual bacterial target cells, fine kinetics of replication, stoichiometry and lysis mediated by these bacteriophages will need to be studied in detail.

Future studies may define define the bacterial hosts for these phages and the fine detail of their replication dynamics in the rumen of cattle. Furthermore, studies are needed to look at whether this involve rapid or slow lysis of their bacterial hosts and whether some, most or all of these phages utilise plasmid encoded bacterial pili and could have a role in targeted intervention to reduce certain conjugation-dependant antimicrobial resistance genes25,28,31. Bacteriophages of the Leviviricetes class are currently under investigation for the design of phage therapies. Indeed, in the context of the now confirmed presence of these bacteriophages in the dairy cow rumen, consideration can be taken into the use of phage therapies using ssRNA bacteriophages to modulate the rumen microbiome for enhanced production efficiency or the treatment of gastrointestinal disease.

Overall, our studies presented here suggest that the studied phage contigs, ssRNA phages of the Class Leviviricetes, are part of a highly diverse and dynamic pattern of infection and clearance, that appear to fluctuate over time, reminiscent of an ongoing predator–prey dynamic somewhat reminiscent of what may be observed in the infant human gut, self-limiting seasonal cholera or over different seasons in marine environments53,54,55,56,57,58. As mainly obligate lytic phages, these ssRNA bacteriophages are likely to play an essential role in maintaining rumen homeostasis. Further studies are needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms of infection and replication and what functional roles the bacteriophages play in the rumen. Nonetheless, our study confirms the abundance and high diversity of Leviviricetes phages in the cow rumen, paving the way for more specific investigations of the above matters.

Data availability

The sequence reads for our samples reported here have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under SRA accession: PRJNA1225943 and PRJNA1225016 and the assembled Leviviricetes contigs deposited in NCBI GenBank under accession numbers PV173603-PV173654. All other data supporting the findings of this manuscript are available in the Tables, the Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gilbert, R. A. et al. Rumen virus populations: Technological advances enhancing current understanding. Front. Microbiol. 11, 450 (2020).

Gilbert, R. A. et al. Toward understanding phage: Host interactions in the rumen; Complete genome sequences of lytic phages infecting rumen bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2340 (2017).

Callanan, J. et al. RNA phage biology in a metagenomic era. Viruses 10, 386 (2018).

Yan, M. et al. Interrogating the viral dark matter of the rumen ecosystem with a global virome database. Nat. Commun. 14, 5254 (2023).

Gilbert, R. A., Dagar, S. S., Kittelmann, S. & Edwards, J. E. Editorial: Advances in the understanding of the commensal eukaryota and viruses of the herbivore gut. Front. Microbiol. 12, 619287 (2021).

Lobo, R. R. & Faciola, A. P. Ruminal phages—A review. Front. Microbiol. 12, 763416 (2021).

Peng, S. et al. First insights into the microbial diversity in the omasum and reticulum of bovine using Illumina sequencing. J. Appl. Genet. 56, 393–401 (2015).

Weimer, P. J., Russell, J. B. & Muck, R. E. Lessons from the cow: What the ruminant animal can teach us about consolidated bioprocessing of cellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 100, 5323–5331 (2009).

Mackie, R. I. Mutualistic fermentative digestion in the gastrointestinal tract: Diversity and evolution1. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 319–326 (2002).

Xie, Y., Sun, H., Xue, M. & Liu, J. Metagenomics reveals differences in microbial composition and metabolic functions in the rumen of dairy cows with different residual feed intake. Anim. Microbiome 4, 19 (2022).

Yan, M. & Yu, Z. Viruses contribute to microbial diversification in the rumen ecosystem and are associated with certain animal production traits. Microbiome 12, 82 (2024).

Callanan, J. et al. Leviviricetes: Expanding and restructuring the taxonomy of bacteria-infecting single-stranded RNA viruses. Microb. Genom. 7, 000686 (2021).

Li, Y., Handley, S. A. & Baldridge, M. T. The dark side of the gut: Virome-host interactions in intestinal homeostasis and disease. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201044 (2021).

Hou, X. et al. Using artificial intelligence to document the hidden RNA virosphere. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.09.027 (2024).

Grabow, W. O. K. Bacteriophages: Update on application as models for viruses in water. Water SA 27, 251–268 (2001).

Wolf, Y. I. et al. Doubling of the known set of RNA viruses by metagenomic analysis of an aquatic virome. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1262–1270 (2020).

Neri, U. et al. Expansion of the global RNA virome reveals diverse clades of bacteriophages. Cell 185, 4023-4037.e18 (2022).

Callanan, J. et al. Expansion of known ssRNA phage genomes: From tens to over a thousand. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay5981 (2020).

Quinones-Olvera, N. et al. Diverse and abundant phages exploit conjugative plasmids. Nat. Commun. 15, 3197 (2024).

Hartard, C., Rivet, R., Banas, S. & Gantzer, C. Occurrence of and sequence variation among F-specific RNA bacteriophage subgroups in feces and wastewater of urban and animal origins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 6505–6515 (2015).

Gorzelnik, K. V. & Zhang, J. Cryo-EM reveals infection steps of single-stranded RNA bacteriophages. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 160, 79–86 (2021).

Thongchol, J., Lill, Z., Hoover, Z. & Zhang, J. Recent advances in structural studies of single-stranded RNA bacteriophages. Viruses 15, 1985 (2023).

Nguyen, H. M. et al. RNA and single-stranded DNA phages: Unveiling the promise from the underexplored world of viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 17029 (2023).

Krishnamurthy, S. R., Janowski, A. B., Zhao, G., Barouch, D. & Wang, D. Hyperexpansion of RNA bacteriophage diversity. PLoS Biol. 14, e1002409 (2016).

Colom, J. et al. Sex pilus specific bacteriophage to drive bacterial population towards antibiotic sensitivity. Sci. Rep. 9, 12616 (2019).

Havelaar, A. H. & Hogeboom, W. M. Factors affecting the enumeration of coliphages in sewage and sewage-polluted waters. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 49, 387–397 (1983).

Manchak, J., Anthony, G. & Frost, L. S. Mutational analysis of F-pilin reveals domains for pilus assembly, phage infection and DNA transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 195–205 (2002).

Penttinen, R., Given, C. & Jalasvuori, M. Indirect selection against antibiotic resistance via specialized plasmid-dependent bacteriophages. Microorganisms 9, 280 (2021).

Li, J., García, P., Ji, X., Wang, R. & He, T. Male-specific bacteriophages and their potential on combating the spreading of T4SS-bearing antimicrobial resistance plasmids. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1080/1040841X.2024.2400150:1-12 (2025).

Daugelavičius, R., Daujotaitė, G. & Bamford, D. H. Lysis physiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infected with ssRNA phage PRR1. Viruses 16, 645 (2024).

Tars, K. ssRNA phages: Life cycle, structure and applications. In Biocommunication of Phages (ed. Witzany, G.) 261–292 (Springer, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45885-0_13.

Thorsteinsson, M. et al. A preliminary study of effects of the red Bonnemaisonia hamifera seaweed on methane emission from dairy cows. JDS Commun. https://doi.org/10.3168/jdsc.2024-0670 (2024).

Kjeldsen, M. H. et al. Phenotypic traits related to methane emissions from Holstein dairy cows challenged by low or high forage proportion. J. Dairy Sci. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2024-24848 (2024).

Krämer, M., Lund, P. & Weisbjerg, M. R. Rumen passage kinetics of forage- and concentrate-derived fiber in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 96, 3163–3176 (2013).

Pinares-Patiño, C. S., Ebrahimi, S. H., McEwan, J. C., Dodds, K. G., Clark, H. & Luo, D. Is rumen retention time implicated in sheep differences in methane emission.

Mambrini, M. & Peyraud, J. Retention time of feed particles and liquids in the stomachs and intestines of dairy cows. Direct measurement and calculations based on faecal collection. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 37, 427–442 (1997).

Dufreneix, F., Faverdin, P. & Peyraud, J. L. Influence of particle size and density on mean retention time in the rumen of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 102, 3010–3022 (2019).

Castledine, M. & Buckling, A. Critically evaluating the relative importance of phage in shaping microbial community composition. Trends Microbiol. 32, 957–969 (2024).

Chevallereau, A., Pons, B. J., van Houte, S. & Westra, E. R. Interactions between bacterial and phage communities in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 49–62 (2022).

De Sordi, L., Lourenço, M. & Debarbieux, L. “I will survive”: A tale of bacteriophage-bacteria coevolution in the gut. Gut Microbes 10, 92–99 (2019).

Thorsteinsson, M., AAS, Noel, S. J., Cai, Z., Niu, Z., Hellwing, A. L. F., Lund, P., Weisbjerg, M. R. & Nielsen, M. O. Effects of the red Bonnemaisonia hamifera seaweed on methane emission from dairy cows. Manuscript in preparation ed, p 35 (2024).

Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing 7 4.3.2 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing %U, Vienna, 2023). https://www.R-project.org/.

Team, R. S. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, RStudio (PBC RStudio, Integrated Development Environment for R, Boston, 2021). http://www.rstudio.com/.

Oksanen, J., Simpson, G. L., Blanchet, F., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O'Hara, R. B., Solymos, P., Stevens, M. H. H., Szoecs, E., Wagner, H., Barbour, M., Bedward, M., Bolker, B., Borcard, D., Carvalho, G., Chirico, M., De Caceres, M., Durand, S., Evangelista, H. B. A., FitzJohn, R., Friendly, M., Furneaux, B., Hannigan, G., Hill, M. O., Lahti, L., McGlinn, D., Ouellette, M.-H., Ribeiro Cunha, E., Smith, T., Stier, A., Ter Braak, C. J. F. & Weedon, J. vegan: Community Ecology Package 7 2.6-4 vegan: Community Ecology Package (2022). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer, New York, 2016). 978-3-319-24277-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

Martinez Arbizu, P. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison Using Adonis R Package Version 0.4.1! (2017).

Anderson, M. J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA), 1–15 (Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat07841.

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D20-d26 (2022).

Thorvaldsdottir, H., Robinson, J. T. & Mesirov, J. P. Integrative genomics viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 14, 178–192 (2013).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Balakrishnan, R. et al. Principles of gene regulation quantitatively connect DNA to RNA and proteins in bacteria. Science 378, eabk2066 (2022).

Kuchina, A. et al. Microbial single-cell RNA sequencing by split-pool barcoding. Science 371, eaba5257 (2021).

Hevroni, G., Flores-Uribe, J., Béjà, O. & Philosof, A. Seasonal and diel patterns of abundance and activity of viruses in the Red Sea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 29738–29747 (2020).

Arkhipova, K. et al. Temporal dynamics of uncultured viruses: A new dimension in viral diversity. ISME J. 12, 199–211 (2018).

Nilsson, E. et al. Genomic and seasonal variations among aquatic phages infecting the Baltic sea gammaproteobacterium Rheinheimera sp. strain BAL341. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e01003 (2019).

Lim, E. S. et al. Early life dynamics of the human gut virome and bacterial microbiome in infants. Nat. Med. 21, 1228–1234 (2015).

Faruque, S. M. et al. Seasonal epidemics of cholera inversely correlate with the prevalence of environmental cholera phages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1702–1707 (2005).

Faruque, S. M. et al. Self-limiting nature of seasonal cholera epidemics: Role of host-mediated amplification of phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6119–6124 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Aarhus University, Department of Animal and Veterinary Sciences for funding support. We express our thanks to the barn staff at AU Viborg—Research Centre Foulum, Tjele, Denmark, for the caretaking of the animals during the experimental period and Lene Rosborg Dal for her technical input.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Aarhus University, Denmark. Experiments, sample collection and sequencing were financed by the Danish Milk Levy Foundation, through the project “Reduced methane production with optimized milk production: Utilization of the interplay between feed additives, genetics of the individual cow and microbes in the rumen”, and the Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries, through the project “Fodring og Fænotype af den klimaeffektive malkeko (FF-ko)” (English: “Feeding and phenotype of the climate efficient dairy cow”), and Maripure ApS, Aalborg, Denmark.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. initiated the study on rumen RNA bacteriophages and did the assembly and selection of contigs and mapping of phage abundances. I.P. checked the dataset provided by S.A. while A.S. provided the statistical input requiring analysis in R. S.J.N., M.T., M.H.K., and A.S. took part in the planning of the animal experimental trials, collected the samples, arranged the sequencing, and provided the metatranscriptomic datasets and sample information. S.A. drafted the initial manuscript with main input from A.S. followed by input from all authors. S.A. and A.S. prepared figures for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alexandersen, S., Polanco, I., Noel, S.J. et al. The dynamics of single stranded, positive sense RNA bacteriophages in the rumen virome. Sci Rep 15, 41435 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26474-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26474-3