Abstract

Reminiscence therapy and exercise therapy have both proven beneficial for individuals with dementia. However, there is limited information on the effects of combining these two approaches in older adults with dementia. Our study aimed to investigate the impact of combined group reminiscence therapy (GRT) and group exercise therapy (GET) on psychological well-being and functional fitness in this population. A total of 32 older adults with mild to moderate dementia living in care homes were randomly assigned into either intervention or usual care groups. The study was conducted from January to June 2021. Intervention: Participants in intervention group received weekly an hour session of GRT and biweekly 1.25-hour session of GET. Reminiscence therapy was based on Remembering Yesterday and Caring Today module, adapted and modified according to participants’ cultural background. GET consisted of stretching, strengthening, aerobic and multicomponent exercises. Outcome measures include the Quality of Life - Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD), Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and Functional Fitness MOT (FFMOT). Independent sample t-test and Mann-Whitney U test show that the participants from the GRT + GET group reported statistically significant higher quality of life and satisfaction with life, with a medium to large effect size. There are no other statistically significant results found for other psychosocial measures. FFMOT was found to deteriorate in both groups with a lesser amount in the intervention group. This study suggests that combined GRT and GET may induce some psychosocial benefits, in particular quality of life and some positive trend in deceleration of functional fitness deterioration among older adults with mild to moderate dementia. Preserving psychological and physical wellbeing is essential for older adults with dementia to maintain their functional independence for as long as possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, 50 million older adults are estimated to have dementia and that number will increase by 10 million every year1. In Malaysia, the population aged 65 years and above is expected to increase from 7.4% (2.4 million) in year 2021 to 14.5% in 2040, nearly doubling in size2. Consequently, the prevalence of dementia is also expected to rise, placing greater demands on Malaysia’s healthcare and social support systems3. A community-based study reported that the prevalence of all-type mild cognitive impairment among individuals aged 60 years and above was 21.1%, which may lead to a higher incidence of dementia later in life4. Another study involving institutionalized older adults in Malaysia found that most participants exhibited some degree of cognitive impairment5.

Non-pharmacological therapies (NPTs) are often preferred as a first-line intervention approach for older adults with dementia. A systematic review on NPTs using 179 RCT studies belonging to 26 intervention categories have shown NPTs as a meaningful, cost effective and resourceful way to improve quality of life (QoL) among people with dementia6. Emphasis is particularly placed on psychosocial interventions which involve interactions between individuals and can show improvements in psychological or social functioning. This includes well-being and cognition, interpersonal relationships, and everyday functional abilities, such as activities of daily living.

Reminiscence therapy is one of the most widely applied psychosocial interventions for people with dementia and caregivers6. While not always the most effective compared to other non-pharmacological interventions such as cognitive stimulation therapy, reality orientation, or music therapy7, reminiscence therapy has consistently shown meaningful benefits in specific domains. Over the past few decades, studies have reported decreases in depressive symptoms8,9, increases in life satisfaction10,11, and improvements in communication12,13. In particular, reminiscence therapy has been associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms and improvements in psychosocial well-being when compared to no therapeutic intervention or treatment as usual14,15. Given that the benefits of reminiscence therapy, while promising, can sometimes be modest or inconsistent when used alone15, researchers have suggested that combining it with other interventions such as physical exercise may produce synergistic effects that enhance both psychological and physical outcomes for older adults with dementia16,17.

In a recent Cochrane systematic review on reminiscence therapy for dementia that consisted of 22 trials encompassing a total of 1972 participants, it was concluded that people with dementia can achieve positive results by engaging in reminiscence work to improve their quality of life, cognition, communication and mood15. In particular, it can achieve these positive results more so in care home settings compared to community settings. It was found that the usage of life story books and multimedia alternatives may induce longer term psychosocial benefits in reminiscence therapy18,19. One study found that Alzheimer’s patients in long term care reported higher quality of life after reminiscence intervention using life-story approach14. Within the Asian context, there are few studies on reminiscence therapy that has been conducted9,12,20. Notably, a study showed that reminiscence therapy had a significant effect on quality of life in a Korean sample, however there was no control group9. Okumura, Tanimukai et al. 20 also found positive effect of reminiscence therapy with a sample of older Japanese female adults, where participants were asked about childhood play, memories triggered by current season, housework, and school memories. A Taiwanese study in reminiscence therapy also supported using more culturally relevant themes to improve psychosocial outcomes12. As there are many different types of reminiscence therapy and settings, its effects show inconsistent results across different studies15.

To expect better outcomes among older adults with dementia, there may be higher potential when combining reminiscence therapy and physical activities such as exercise. Generally, it is essential that exercises are task orientated21,22 and of sufficient intensity23,24 for optimal benefits in rehabilitation. There is an abundance of evidence on the positive effects of exercise on cognitive health among healthy older adults25. On the other hand, evidence on the effects of exercise on quality of life as a stand-alone intervention among older adults with dementia is inconclusive26. The neurophysiological hypothesis suggests that physical and cognitive-related training may exert synergistic effects by stimulating the formation of new synaptic pathways in the brain, thereby enhancing health and well-being22. Integrated multiple interventions have been found to be more effective for frail older adults27. In particular, a study pointed out psychosocial treatments are more likely to benefit the older adults if involving imagery and exercise28. Fujita, Ito et al. 17 in a combined therapy also found positive results when combining reminiscence therapy, exercise and music. This suggests that the features of both reminiscence therapy and exercise therapy can be complimentary in inducing psychological and physical wellbeing among older adults with dementia.

In Malaysia, the efficacy of the combination of these interventions to enhance psychological well-being and functional fitness is has not been studied. Research in this area is required to see whether what has been achieved in western contexts can be replicated in an Asian culture and context. Following recommendations from past research, reminiscence therapy and exercise therapy appears to have more promising effects among care home older adults. Thus, we hypothesized that the effects of combined group reminiscence therapy (GRT) and group exercise therapy (GET) among older adults with mild to moderate dementia will produce a significant outcome on psychological and physical wellbeing.

Method

Design

This study was a preliminary randomized controlled trial with two parallel arms, conducted in a single-blind manner, pre and post assessment at 12 weeks. All data were collected from January 2021 to June 2021 and data was analysed in July 2021.

Participants

Participants in this study were recruited from a residential care home under the Department of Social Welfare, Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development, Malaysia (JKMM), which housed a total of 326 residents. Following approval from JKMM, the home’s welfare officers, together with the researcher (PS), reviewed the list of residents to identify potential participants.

For inclusion, residents were required to be aged 60 years and above, have a diagnosis of dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and fall within the mild to moderate dementia range as assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). A CDR score of 1 indicated mild dementia and a score of 2 indicated moderate dementia29. In addition, participants needed to demonstrate sufficient mental capacity to provide informed consent (witnessed by professional care staff) and to be able to walk independently without walking aids.

Exclusion criteria included having a CDR score of 0, 0.5, or 3; a history of severe neurological conditions (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy); major psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe or chronic depression); major cardiac disorders or other severe medical conditions; severe uncorrected vision or hearing impairment; loss of independence in basic activities of daily living (ADL); current participation in other research projects; and inability to communicate in Malay to complete assessment and to participate in intervention session. It should be noted that while individuals with major psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, chronic severe depression) were excluded, participants with mild to moderate anxiety or depressive symptoms were eligible for inclusion. This distinction was made because such symptoms commonly co-occur with dementia and may be responsive to psychosocial interventions. Information regarding neurological and psychiatric diagnoses was obtained primarily from medical records and verified with care staff. These criteria were applied to ensure participant safety, the feasibility of participation in both physical and reminiscence activities, and to minimize confounding variables. For instance, individuals with severe psychiatric disorders might have required specialized care beyond the scope of this intervention, while those with advanced neurological conditions would not have been able to engage safely in group-based exercise.

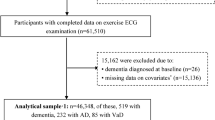

From the initial 326 residents, 237 were excluded because they did not meet the age or dementia criteria. Of the 89 residents shortlisted for further eligibility assessment, 23 were excluded due to questionable dementia (CDR = 0.5), 22 declined participations, 6 were excluded due to psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia or chronic depression), 3 were excluded due to stroke-related speech impairments, and 3 were excluded due to inability to communicate in Malay. The final 32 participants met al.l eligibility criteria and were enrolled in the study. Participants were allocated into either the experimental group or the ‘treatment as usual’ control group following baseline assessment, using the minimization method to balance age and dementia severity between groups. This method ensures equally balanced groups although the sample size is small and is reported as a valid option30. (see Fig. 1).

Procedure

This trial obtained ethical approval from Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. The clinical trial was registered at Protocol Registration and Results System with number UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-701 (11/01/2020). This study was executed according to the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for studies on humans.

Potential participants were identified after obtaining approval from The Department of Social Welfare, Malaysia study (approval no: UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-701.), a government agency to manage Rumah Sri Kenangan (RSK, care homes). After a formal meeting and briefing with RSK management, eligible participants were identified from the residents’ name list by welfare officers together with researcher (PS). The researchers then carried on with screening to ascertain eligibility according to inclusion criteria. In addition, written informed consent was obtained from participants and witnessed by care staff.

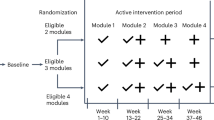

Following base-line assessments, participants were randomized either to the ‘GRT + GET’ group or ‘care as usual’ group. Participants in ‘GRT + GET’ group received 12 group sessions of reminiscence therapy and 24 physical exercise sessions. Meanwhile participants in control group continued to receive their care as usual over the 12-week period. After ‘GRT + GET’ intervention was completed, immediate post-assessment at the 12th week period from baseline were completed. Participants in treatment group received Ringgit Malaysia 5.00 (approximately 1.2 USD) as a token for each GRT and GET session, including baseline and post assessment. Meanwhile participants in ‘treatment as usual’ group only received token at baseline and post assessment.

Intervention

The interventions for this study consisted of two major components: Group Reminiscence Therapy (GRT) and Group Exercise Therapy (GET). For GRT, the therapist (PS) is a qualified clinical psychologist and trained in group reminiscence work. The module adaptation to suit Malay culture, planning and preparation were completed by PS and a social work expert (KA) for older adults. Meanwhile, the training and supervision for GET intervention regime was provided by an expert and qualified Physiotherapist (DKA). The GET was led by a final year physiotherapy student (LEV) with assistance from other physiotherapy students. The GRT was held for 1 h 30 min weekly (every Friday), GET was held for 75 min, twice weekly (every Monday and Wednesday). Both GRT and GET were completed in 12 consecutive weeks.

Reminiscence therapy

The Group Reminiscence Therapy (GRT) was held for 1 h 30 min weekly (every Friday) for 12 consecutive weeks based on ‘Remembering Yesterday and Caring Today’ (RYCT) module31. This module consists of 12 reminiscence themes covered topics such as childhood memories, school days, family life and marriage, work experiences, festivals and cultural traditions, food and cooking, hobbies and leisure activities, music and favourite songs, important life events, travel and places lived, friends and community life, and reflections on life achievements. Each session involved structured prompts, group sharing, and the use of photos, music, and objects to stimulate memory and discussion. The content of each theme was adopted according to participants’ cultural background and Malay language. Each session/theme was supported with video clips, music/song, tangible items, posters, photos, games, dress, pictures, role play, drawing, and writing. Sessions started with an introduction of the theme of the week, and the activities that followed. Participants were encouraged to share their life experiences according to theme and the therapist would prompt to increase interaction among participants in group. For example, during ‘school day’ theme, a classroom situation was re-enacted with relevant things such as posters, small blackboard, old books. The therapist and assistant therapist dressed-up as an old-fashioned teacher with a name tag. The session started with the ‘students’ (participants) standing and wishing the ‘teachers’, followed by ‘teacher’ with a ruler checking each ‘student’ on their fingernails and hair. Participants were asked ‘why are their nails long?’, ‘why didn’t they cut their nails?’ And/or ‘Why is their hair too long?’. Participants were encouraged to share whether they have such experience during school days. A 7–8 min famous video clip of ‘Cikgu Saari’ (acted by P.Ramlee) from Masam-Masam Manis (Malay movie) was played to reflect ‘visible’ memories. This was followed by simple arts and crafts in group of 3 to 4. After each activity, therapists led an open discussion related to ‘school days’ reminiscence questions for participants to share within the group.

Exercise therapy

The Group Exercise Therapy (GET) program consisted of 24 sessions conducted twice weekly, each lasting approximately 60 min. Sessions were adapted from standardized geriatric exercise protocols and included a structured sequence of activities: a 10-minute warm-up involving breathing exercises and light stretching; 15 min of aerobic exercises such as marching in place, rhythmic stepping, or low-impact walking movements to music; 15 min of strength training using resistance bands or light weights to target major muscle groups; 10 min of balance and flexibility activities such as heel-to-toe walking, single-leg stance, and dynamic balance tasks; and a 10-minute cool-down with gentle stretches and relaxation techniques. Progression was achieved by gradually increasing repetitions, resistance, and the complexity of movements across the 12-week program.

Measures

The baseline assessment was carried out by the researcher team (PS, DKA and LEV) with assistance from clinical psychology master students and final year physiotherapy undergraduate students. The post intervention assessments were carried by the same students and a physiotherapist, who are blind to the allocated condition under direct supervision of PS and DKA. All the students received training on measures. The data was collected at baseline and at 12 weeks, which is the end of intervention.

Clinical dementia rating (CDR) scale29

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) was utilized to assess the severity or stage of dementia. The scale assigns the following grades: 0 for none, 0.5 for questionable, 1 for mild, 2 for moderate, and 3 for severe. It evaluates various domains including memory, orientation, judgment, problem-solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care. The severity of dementia based on CDR was rated after feedback from home officers, care staffs, nurses and face-to-face interviews with the participants. The reliability and validity of this scale has been established widely among Asian populations32. Older adults who scored 1 and 2 were recruited.

Malay version mini mental state examination (MMSE)

The global cognitive function of the participants was assessed using MMSE during screening and also as outcome measure. The Malay version of MMSE (M-MMSE) was used33. The M-MMSE was validated based on 185 older adults from 8 old folks’ home, a population similar to current study sample. The M-MMSE mean score was 17.78±4.51 (range; 7 to 27). The sensitivity and specificity of the M-MMSE was 0.97% and 61% respectively33.

Frailty status34

Frailty criteria suggested by Fried et al. were used to screen the frailty status of the participants34. According to Fried et al. the frailty criteria were slow walking speed, weakness, low physical activity, exhaustion and unintentional weight loss34.

Quality of Life - Alzheimer’s disease (QOL-AD)

Quality of Life - Alzheimer’s disease (QOL-AD) was used as a primary outcome measure in this study to examine the participants’ quality of life before and after the intervention. This questionnaire consisted of 13 items which include relationship, mood, life situation and physical activity. QOL-AD score ranges from 13 to 52 with higher scores indicating better quality of life35. The Malay version of QOL-AD (QOL-Malay) was used36. This tool was translated according to standard guideline for cross-cultural adaption of measure. It had an alpha of 0.82 and explained 66% of variance. The intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.7736.

Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III (ACE-III)37

ACE-III is a concise cognitive test that evaluates five domains: attention, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) shows a significant correlation with the Clinical Dementia Scale (r = -.321, p <.001)38. The Malay version of ACE-III (M-ACE-III) was used for this study. M-ACE-III was reported to have alpha coefficients of 0.829 and intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.959. The M-ACE-III cut-off score to detect dementia vs. healthy subject was 74/75 (sensitivity = 90.6%, specificity = 82.0%)39. For this study, the M-ACE-III scores were used to detect changes in cognition post intervention.

Beck anxiety inventory (BAI)

The BAI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess anxiety symptoms. Participants rate the severity of each symptom that bothers them on a four-point scale, ranging from “not at all” (0) to “severely” (3). The BAI demonstrates good internal consistency (α = 0.92) and high test-retest reliability (r =.75). The Malay version of BAI (BAI-Malay) was used40. Overall Cronbach alpha value for BAI-Malay was 0.91, with acceptable concurrent validity, ranging between r =.22 to r =.67. Although individuals with major psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, chronic severe depression) were excluded from participation, those with mild to moderate anxiety symptoms were eligible, as such symptoms are common in dementia and can be targeted by psychosocial interventions. The BAI was therefore included to evaluate whether the combined reminiscence and exercise intervention reduced co-occurring anxiety among participants.

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS)39

The SWLS is a 5-items questionnaire, using a 7-point scale, ranging from 7 ‘strongly agree’ to 1 ‘strongly disagree’, on the perception of satisfaction in life. SWLS items are more emotional rather than cognitive41. The Malay version of SWLS was used (40). The Malay version of SWLS also has good internal consistency (a = 0.83), with Confirmatory Factor Analysis supporting the unidimensional factor structure of the original version42.

Geriatric depression scale (GDS)

GDS is a 15-item scale commonly used to monitor depression among older adults. The present study used modified Malay version of GDS-14 instead of GDS-15 as it was found reliable among Malaysian older adults43. The modified Malay version GDS has sensitivity of 0.96 and specificity of 0.84, and sensitivity of 1.00 and specificity of 0.92 to detect mild and severe depression respectively43. Although participants with major psychiatric disorders were excluded, the GDS was included because mild to moderate depressive symptoms frequently co-occur with dementia. Monitoring these symptoms allowed the study to assess whether the intervention provided secondary benefits in reducing depressive symptomatology in this population.

Functional fitness MOT (FFMOT)

FFMOT was used to assess functional fitness, comprising the following tests: the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), the 30-second chair stand test (30-s CST), chair sit and reach, back scratch, timed 8-feet up and go, one-legged stance, and hand grip strength. Functional fitness was evaluated using the Senior Fitness test battery, which includes six items specifically designed and validated to assess the physiological parameters that support physical mobility in older adults44,45. The test-retest reliabilities of the Senior Fitness test battery range from 0.90 to 0.96 for the 30-s CST, chair sit-and-reach, back scratch, 6-minute walk, and timed 8-foot up and go tests45. However, the 6MWT was replaced by 2-minute walk test (2MWT). 2MWT is a reliable alternative, in evaluating the exercise capacity of older adults at levels corresponding more to efforts during daily activities, modified from six-minute walk test (6MWT). Test–retest reliability of 0.94 and 0.95 were obtained by Connelly, Thomas et al46.. This study illustrated the use of reliability coefficients in clinical practice for 2MWT. The construct validity of 2MWT in older adults showed an excellent correlation with the 6MWT (r =.93) and an excellent correlation with the Timed Up and Go test (r = -.87)46. The One-Legged Stance Test is a straightforward and efficient assessment of static balance, applicable to both adults with locomotor dysfunction and athletes. This test measures the duration of time a person can maintain a single-limb stance with their eyes open, and it can also be repeated with eyes closed. The SLS Test has shown strong intersubject reliability (ICC = 0.73) and excellent interrater reliability (ICC = 0.75–0.998)47,48. A reliability test was conducted to assess the test-retest reliability of the handgrip strength test in older adults with varying levels of dementia, as classified by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)47,49. The results showed excellent test-retest reliability for participants with borderline dementia (ICC = 0.975; p =.001), mild dementia (ICC = 0.968; p =.002), and moderate dementia (ICC = 0.964; p =.001) (47).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Version 26 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software. An a priori power analysis was conducted using GPower 3.1 for repeated-measures ANOVA with two groups and two time points. The analysis indicated that a minimum of 34 participants (17 per group) was required to detect a medium effect size (f = 0.25) with α = 0.05 and 80% power. Although 32 participants were initially recruited, attrition reduced the final analyzed sample to 30, which fell slightly short of the calculated requirement. An independent samples t-test was applied to continuous variables, while Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables to compare baseline differences between the groups. To measure the effects of the intervention, both one-way ANCOVA and independent samples t-test were employed. Statistical assumptions for one-way ANCOVA and independent samples t-test that include independence, normality, homogeneity of regression slopes, linearity and homogeneity of variance were checked prior the data analysis. Missing data were handled using available-case analysis. Only participants with both baseline and post-intervention data were included in the final analyses. As the sample size was small, no imputation methods were applied for missing outcome data.

Results

Demographic and descriptive results

A total of 30 participants completed the post-intervention assessment, with 14 in the treatment-as-usual (TAU) group and 16 in the GRT + GET group. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participants by group as well as overall. The mean age of the overall sample was 71.10 years (SD = 6.72; range 63–87), and just over half were male (53.3%). Most participants (60.0%) had completed only primary education, and 40.0% had never married. In terms of clinical characteristics, 90.0% were classified as having mild dementia (CDR = 1), with an overall mean MMSE score of 17.33 (SD = 4.03). More than half of the participants (56.7%) were considered frail according to frailty status. No significant demographic differences were found between the two groups.

Response rate

A total 12 GRT and 24 GET sessions were conducted. 13 participants (81%) in GRT attended all sessions, 2 participants missed 1 session due to appointments with doctors (attendance rate; 92%) and 1 participant missed 2 consecutive sessions because of personal reasons (attendance rate; 83%). Meanwhile in GET, 12 participants (75%) completed all exercise sessions. 1 participant missed 4 sessions (attendance rate; 83%), 2 participants missed 3 sessions (attendance rate 88%) and 1 participant missed 2 sessions (attendance rate 92%). Participants who missed occasional sessions were not excluded from the analysis, provided they completed both baseline and post-intervention assessments. Missed intervention sessions were treated as non-attendance and were not replaced by imputation. Outcome analyses were conducted using available data from participants who completed both time points (per-protocol analysis).

Baseline differences

There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, education, gender, marital status, CDR, MMSE and frailty status. In terms of outcome measures at baseline, there were no significant differences between 2 groups in all outcome measures: MMSE, ACE-III, BAI, SWLS, GDS and FFMOT measures, except for QOL-AD.

Main outcome results

Table 2 shows the means and SDs for QOL-AD, ACE-III, BAI, SWLS, MMSE, GDS and FFMOT at baseline and post intervention.

One-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA)

One-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to assess the impact of the intervention on participants’ physical and mental health. Since the baseline score was anticipated to influence this relationship, it was measured and included as a covariate in the analysis.

Before interpreting the outcome of the ANCOVA, its assumptions were tested. Only the ANCOVA outcomes for the variables including QOL-AD, ACE-III, BAI, SWLS, GDS, MMSE, 2MWT, 30 s Chair stand, chair sit and reach, timed 8 ft up and go, and one-legged stance are valid as the other variables did not fulfill the assumptions of ANCOVA. All results were not statistically significant.

Independent sample t-test

Independent samples t-test was used to compare the pre-post differences of the measures as reported by the participants in the TAU (n = 14) and GET + GRT group (n = 16). Table 3 shows the differences mean and SDs for pre-post QOL-AD, ACE-III, BAI. SWLS, GDS and FFMOT scores.

As the assumption of normality was violated for MMSE, SWLS, Chair Sit and Reach, timed 8-feet up and go, and one-legged stance, Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to measure the presence of significance pre-post difference between TAU and GET + GRT group. Out of the independent sample t-tests, only the t-test for QOL-AD was statistically significant, with GRT + GET group (M = 5.00, SD = 5.54) reporting better quality of life, 95% CI (−11.44, −1.98), than the TAU group (M = −1.71, SD = 7.10), t (28) = −2.91, p <.007, two-tailed, d = 1.05. This effect can be described as a large effect size.

For Mann-Whitney U tests, only the analysis for SWLS was statistically significant. The analysis indicated that the SWLS of the participants from GRT + GET group (Mean Rank = 18.63, n = 16) were significantly higher than those of the TAU group (Mean Rank = 11.93, n = 14), U = 62.00, p <.037, two-tailed. This effect can be described as “medium” (r =.38).

ANCOVA and independent sample t-test analysis were conducted for the subscale of ACE-III, namely attention, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities, and no significant results was found.

Discussion

Generally, both reminiscence work and physical exercises are beneficial for people with cognitive decline. The present study is a preliminary randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of combined Group Reminiscence Therapy (GRT) and Group Exercise Therapy (GET) on psychological and physical wellbeing among older adults with mild to moderate dementia living in care homes in Malaysia. Results from this study show that the combined intervention of GRT and GET, which lasts for about one hour three times a week for 12 consecutive weeks, have significantly improved the quality of life and life satisfaction in older adults with dementia compared to the group of older adults with dementia receiving only standard care.

It is important to note that differences were observed between the ANCOVA and independent t-test/Mann–Whitney analyses for QOL-AD and SWLS. The independent sample tests compared post-test scores directly, while ANCOVA adjusted for baseline differences, yielding a more conservative estimate of intervention effects. In this study, small baseline imbalances and the relatively small sample size likely reduced the statistical power of the ANCOVA, resulting in non-significant findings despite significant differences indicated by the unadjusted tests. This suggests that the intervention may have had a positive effect on quality of life and life satisfaction, although results should be interpreted with caution.

The positive results on quality of life showed consistency with previous studies on reminiscence work9,14 and physical exercise50,51. These results can support the hypothesis that combined modalities in training or therapy can result in positive outcomes for older adults with dementia. However, the QoL improvement in ‘GRT + GET’ group of about five points which is commonly achievable even when conducting reminiscence therapy or exercise therapy alone19,52. Additionally, the improvement of QoL in the experimental group of this study could be observed because of the evident chronic deficiency of meaningful cognitive and physical activities in residential homes for the older adults. The lack of meaningful activities for older adults within residential homes is common even in developed countries53, and remains a major concern for developing nations like Malaysia. Positive results for QOL especially in care home settings is consistent with findings by Woods, Spector et al. 15. Participants in the intervention group have reported ‘never involved in such activities and were happy’ to be part of study and were saddened when told that the study would be completed. Some have indicated ‘nothing to do after this’ after the study concluded. Further research is required to see whether different activities that can instill sense of meaning among older adults can also have positive effects on their wellbeing. It would also be good to compare effects with older adults in community settings.

For depressive symptoms, assessed using the GDS, a positive but non-significant effect was observed. In the present study, the intervention did not produce significant improvements in depressive symptoms or cognitive performance, which contrasts with prior studies reporting positive effects of reminiscence therapy and combined interventions9,10,14,15,17,27. Notably, Azcurra15 explicitly excluded individuals with major psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and major affective disorders as well as those with unstable medical conditions. In contrast, many of the other studies (e.g., those included in meta-analyses and systematic reviews) did not consistently specify such exclusions, which may indicate inclusion of participants with higher baseline severity of depression or cognitive impairment. Our more stringent eligibility criteria excluding major psychiatric and neurological conditions likely reduced baseline variability, thereby diminishing the likelihood of detecting statistically significant changes in depression or cognition.

Cognitive performance showed a positive trend in ‘GRT + GET’ group but the improvement is not statistically different between groups. The present non-significant findings on cognition showed inconsistencies with past findings regarding the cognitive effects of therapies25,54. This non-significant performance on cognition may be due to ACE-III being a more demanding test since majority of participants are low in education and physically frail.

Both the control and intervention groups showed decrease in life satisfaction score, but it was noted that the decrease among the intervention group is statistically significant less than the TAU group. This finding is consistent with findings which reported significant improvement in GRT intervention10,55,56. The decrease in life satisfactions may be due to external factors such as lack of fulfilling care within a care home setting, which leads to lower sense of life satisfaction. As reported, there are generally a lack of meaningful recreational activities in Malaysian care homes, and while the activities of this study have been found meaningful and interesting to the participants, the effects may not be as prominent when taking into account the effects of their immediate environment.

In terms of physical well-being, the present study did not establish statistically significant outcomes between groups. However, some of the trends in the results were congruent with past findings. For example, less deterioration in handgrip strength in intervention group was consistent with past findings on physical exercise57. To note, 75% of participants in intervention group are considered frail according to the frailty test compared to the control group where only 37.5% were frail. The physical activities of older adults measured in this study using physical activity scale of elderly (PASE) also showed that 81.25% participants in ‘GRT + GET’ group were ‘not normal’ compared to 75% of participants in control group. The baseline measure of older adults in FFMOT was also lower than the normative data of some past research44,48,57. The frailty of older adults may have restricted participation in physical activities and contributed to weak baseline measures of functional fitness. It is uncertain whether this can lead to worsened wellbeing scores, as there has also been a study on older adults with difference in frailty status reporting equivalent scores on wellbeing in past research50.

In conclusion, the results of our preliminary randomized controlled trial support the hypothesis that combined group reminiscence therapy and group exercise therapy supports quality of life and life satisfaction, thus enhancing psychological and physical wellbeing among older adults with mild to moderate dementia in care home settings.

Conclusions and recommendation

The aim of our study was to investigate the effects of combined group reminiscence therapy (GRT) and group exercise therapy (GET) on psychological wellbeing and functional fitness among older adults with dementia. The findings revealed the participants from the group reminiscence therapy and group exercise therapy group reported statistically significant higher quality of life and satisfaction with life, with a medium to large effect size. There are no other statistically significant results found for other psychosocial measures. Functional Fitness MOT was found to deteriorate in both groups with a lesser amount in the intervention group. These results study suggest that combined GRT and GET may induce some psychosocial benefits, in particular quality of life and some positive trend in deceleration of functional fitness deterioration among older adults with mild to moderate dementia. It is important to preserve psychological and physical wellbeing to maintain functional independence as long as possible among older adults with dementia. Maintaining mental and physical health is crucial for older adults with dementia to preserve their functional independence for as long as possible. Additionally, it is recommended that all healthcare professionals working with older adults implement “memory therapy,” which is tailored to the individual’s needs and physiological characteristics. This approach promotes mental well-being and functional fitness, protects against chronic diseases, and enhances overall quality of life.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting and generalizing the findings. First, it was difficult to recruit a sufficient number of participants who could commit to the program, resulting in a small sample size that affected the statistical power of the study. Although an a priori power analysis indicated that 34 participants were required to achieve adequate power to detect medium effect sizes (f = 0.25, α = 0.05, power = 0.80), the final analyzed sample included only 30 participants due to attrition. This shortfall likely reduced statistical power, and therefore the non-significant findings for depressive symptoms and cognitive performance may reflect insufficient power rather than the absence of an intervention effect. Second, all participants were recruited from a single residential care home, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations and settings. Third, missing data were handled using available-case analysis, and no multiple imputation or weighting procedures were applied, which may have introduced attrition bias. Fourth, three of the instruments used (BAI-Malay, QOL-Malay, and M-ACE) were translated versions of original scales and, as relatively new adaptations, may require further validation within the Malaysian population. Finally, the settings for the life story activity may be difficult to replicate for other researchers, particularly those working in different cultural contexts.

Future research should consider larger multi-site trials with more diverse samples to increase generalizability. Studies employing longer follow-up periods are needed to examine the sustainability of intervention effects. In addition, future work should use advanced methods such as multiple imputation to handle missing data and reduce bias associated with attrition.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Organization DGWH. Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization. In. Dementia. (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021)

Malaysia DoS. Current Population Estimates (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2021).

Mafauzy, M. The problems and challenges of the aging population of Malaysia. Malaysian J. Med. Sciences: MJMS. 7 (1), 1–3 (2000). e-pub ahead of print 2000/01/01;.

Lee, L. K. et al. Prevalence of gender disparities and predictors affecting the occurrence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 54 (1), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2011.03.015 (2012). e-pub ahead of print 2011/05/07.

Murukesu, R. R. et al. Prevalence of Frailty and its Association with Cognitive Status and Functional Fitness among Ambulating Older Adults Residing in Institutions within West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. International journal of environmental research and public health. 16 (23) e-pub ahead of print 2019/11/30 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234716 (2019).

Subramaniam, P. & Woods, B. The impact of individual reminiscence therapy for people with dementia: systematic review. Expert Rev. Neurother. 12 (5), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.35 (2012).

Olazarán, J. et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of efficacy. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 30, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1159/000316119 (2010).

Choy, J. C. P. & Lou, V. W. Q. Effectiveness of the modified instrumental reminiscence intervention on psychological Well-Being among Community-Dwelling Chinese older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Geriatric Psychiatry. 24 (1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.008 (2016).

Jo, H. & Song, E. J. E. The effect of reminiscence therapy on depression, quality of life, ego-integrity, social behavior function, and activies of daily living in elderly patients with mild dementia. ; 41(1): 1–13. (2015).

Bohlmeijer, E., Smit, F. & Cuijpers, P. J. I. Effects of reminiscence and life review on late-life depression: a meta‐analysis. 18 (12): 1088–1094 (2003).

Pinquart, M. & Forstmeier, S. Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment. Health. 16 (5), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.651434 (2012). e-pub ahead of print 2012/02/07.

Chang, H. & Chien, H-W-J-D. Effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for people living with dementia in a day care centers in Taiwan. 17 (7), 924–935 (2018).

Moss, S. E., Polignano, E., White, C. L., Minichiello, M. D. & Sunderland, T. Reminiscence group activities and discourse interaction in alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 28 (8), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.3928/0098-9134-20020801-09 (2002). e-pub ahead of print 2002/09/11.

Azcurra DJLSJRBdP. A reminiscence program intervention to improve the quality of life of long-term care residents with Alzheimer’s disease. A randomized controlled trial. ; 34(4): 422–433. (2012).

Woods, B., Spector, A., Jones, C., Orrell, M. & Davies, S. Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In: Issue. (2005).

Dedeyne, L., Deschodt, M., Verschueren, S., Tournoy, J. & Gielen, E. Effects of multi-domain interventions in (pre)frail elderly on frailty, functional, and cognitive status: a systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging. 12, 873–896. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S130794 (2017). e-pub ahead of print 2017/06/06.

Fujita, T., Ito, A., Kikuchi, N., Kakinuma, T. & Sato, Y. J. J. Effects of compound music program on cognitive function and QOL in community-dwelling elderly. ; 28(11): 3209–3212. (2016).

Subramaniam, P. & Woods, B. Digital life storybooks for people with dementia living in care homes: an evaluation. Clin. Interv. Aging. 11, 1263–1276. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S111097 (2016). e-pub ahead of print 2016/10/05.

Subramaniam, P., Woods, B., Whitaker, C. J. A. & health m. Life review and life story books for people with mild to moderate dementia: a randomised controlled trial. 18 (3), 363–375 (2014).

Okumura, Y., Tanimukai, S. & Asada, T. J. P. Effects of short-term reminiscence therapy on elderly with dementia: A comparison with everyday conversation approaches. ; 8(3): 124–133. (2008).

De Vreede, P. L., Samson, M. M., Van Meeteren, N. L., Duursma, S. A. & Verhaar, H. J. J. J. A. G. S. Functional-task exercise versus resistance strength exercise to improve daily function in older women: a randomized, controlled trial. ; 53(1): 2–10. (2005).

Law, L. L., Barnett, F., Yau, M. K. & Gray, M. A. J. O. Development and Initial Testing of Functional Task Exercise on Older Adults with Cognitive Impairment at Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease–FcTSim Programme–A Feasibility Study. 20 (4), 185–197 (2013).

Liu, C.J. & Latham, N.K. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults.Cochrane Database Syst.2009(3), CD002759. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002759 (2009).

Singh, M. A. F. J. T. J. G. S. A. B. S. & Sciences, M. Exercise comes of age: rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. 57 (5), M262–M282 (2002).

Sabia, S. et al. Physical activity, cognitive decline, and risk of dementia: 28 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. ; 357. (2017).

Ojagbemi, A. & Akin-Ojagbemi, N. J. J. A. G. Exercise and quality of life in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. 38 (1), 27–48 (2019).

Dedeyne, L., Deschodt, M., Verschueren, S., Tournoy, J. & Gielen, E. J. C. Effects of multi-domain interventions in (pre) frail elderly on frailty, functional, and cognitive status: a systematic review. 873–896 (2017).

Harvey, A.G. et al. Improving outcome of psychosocial treatments by enhancing memory and learning. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614521781 (2014).

Hughes, C.P., Berg, L., Danziger, W.L., Coben, L.A. & Martin, R.L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 140(6), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.140.6.566 (1982).

Altman, D. G. & Bland, J. M. J. B. Treatment allocation by minimisation. 330 (7495), 843 (2005).

Schweitzer, P. & Bruce, E. Remembering yesterday, Caring Today: Reminiscence in Dementia Care: A Guide To Good Practice (Jessica Kingsley, 2008).

Lim, W. S. & Chong, M. S. Sahadevan SJCm, research. Utility of the clinical dementia rating in Asian populations. 5 (1), 61–70 (2007).

Zarina, Z.A., Zahiruddin, O. & Che Wan, A.H. Validation of Malay Mini Mental State Examination. Malays. J. Psychiatry. 16(1): 16-17 (2007).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. 56 (3), M146–M157 (2001).

Hoe, J., Katona, C., Roch, B. & Livingston, G. Use of the QOL-AD for measuring quality of life in people with severe dementia—the LASER-AD study. Age Ageing. 34(2), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afi030 (2005).

Kan, K. C., Subramaniam, P., Razali, R. & Ghazali, S. E. J. M. J. P. H. M. Reliability and validity of the quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease questionnaire in Malay Language for Malaysian older adult with dementia. 19 (1), 56–63 (2019).

Hsieh, S., Schubert, S., Hoon, C., Mioshi, E. & Hodges, J.R. Validation of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination III in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord.V 36(3 – 4), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351671 (2013).

Mioshi, E., Dawson, K., Mitchell, J. & Arnold, R. Hodges JRJIJoGPAjotpoll, sciences a. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. 21(11), 1078–1085 (2006).

Kan, K. C. et al. Validation of the Malay version of addenbrooke’s cognitive examination III in detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Dement. Geriatric Cogn. Disorders Extra. 9 (1), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495107 (2019). e-pub ahead of print 2019/05/03.

Mukhtar, F. & Zulkefly, N. S. The Beck anxiety inventory for Malays (BAI-Malay): A preliminary study on psychometric properties. Malaysian J. Med. Health Sci. 7, 73–79 (2011).

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49 (1), 71–75 (1985).

Swami, V. & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. J. S. I. R. Psychometric evaluation of the Malay satisfaction with life scale. 92 (1), 25–33 (2009).

Ewe, E. & Che Ismail, H. J. A. Validation of Malay version of geriatric depression scale among elderly inpatients. ; 17: 65. (2004).

Rikli, R.E. & Jones, C.J. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults aged 60–94. J. Aging Phys. Act. 7(2), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.7.2.162 (1999).

Rikli, R.E. & Jones, C.J. Development and validation of criterion-referenced clinically relevant fitness standards for maintaining physical independence in later years. Gerontologist. 53(2), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns071 (2013).

Connelly, D., Thomas, B., Cliffe, S., Perry, W. & Smith, R. J. P. C. Clinical utility of the 2-minute walk test for older adults living in long-term care. 61 (2), 78–87 (2009).

Mancini, M. & Horak, F. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 46(2), 239–248 (2010).

Springer, B. A., Marin, R., Cyhan, T., Roberts, H. & Gill, N. W. J. J. Normative values for the unipedal stance test with eyes open and closed. 30 (1), 8–15 (2007).

Alencar, M. A., Dias, J., Figueiredo, L. C. & Dias, R. C. J. B. J. P. T. Handgrip strength in elderly with dementia: study of reliability. ; 16: 510–514. (2012).

Langlois, F. et al. Benefits of physical exercise training on cognition and quality of life in frail older adults. 68 (3), 400–404 (2013).

Tavares, B. B., Moraes, H. & Deslandes, A. C. Laks JJTip, psychotherapy. Impact of physical exercise on quality of life of older adults with depression or Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. ; 36(3): 134–139. (2014).

Sampaio, A., Marques-Aleixo, I., Seabra, A., Mota, J. & Carvalho, J. J. B. Physical exercise for individuals with dementia: potential benefits perceived by formal caregivers. 21 (1), 6 (2021).

Boyd, A., Payne, J., Hutcheson, C. & Bell, S. J. B. J. M. H. N. Bored to death: tackling lack of activity in care homes. 1 (4), 232–237 (2012).

Duru Aşiret, G. & Kapucu, S. The effect of reminiscence therapy on cognition, depression, and activities of daily living for patients with Alzheimer disease. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 29(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988715598233 (2016).

Lin, Y. C., Dai, Y. T. & Hwang, S. L. J. P. The effect of reminiscence on the elderly population: a systematic review. 20 (4), 297–306 (2003).

Pinquart, M., Forstmeier, S. J. A. & health m. Effects of reminiscence interventions on psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. 16 (5), 541–558 (2012).

Dodds, R. M. et al. Grip strength across the life course: normative data from twelve British studies. 9 (12), e113637 (2014).

Funding

This study was funded using grants: Komuniti-2013-027. This work was supported and funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R707), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S., D.K.A.S., L.E.V, M. H., and K.A. Data Analysis: H.X.J., T.K.W. H. F. A and P.S. Resources: P.S, H. F. A., M.H., and D.K.A.S. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: L.E.V., H.X.J., H. F. A., M. H., and T.K.W. Writing—Review & Editing: P.S., D.K.A.S., H. F. A., M. H., and K.A. Funding Acquisition: P.S and H. F. A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participation

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (RECUKM) (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-701).

This trial obtained ethical approval from Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. The clinical trial was registered at Protocol Registration and Results System with number UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-701 (11/01/2020). Participation in this study was voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. This study was executed according to the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for studies on humans.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents of study participants.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to P. S.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramaniam, P., Singh, D.K.A., AL-shahrani, H.F. et al. Effects of combined group reminiscence and exercise therapy on psychological wellbeing and functional fitness among older adults with dementia. Sci Rep 15, 42449 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26503-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26503-1