Abstract

This retrospective cohort study examined the association between admission blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels and mortality in critically ill acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients from the MIMIC-IV database. Patients were stratified into quartiles based on admission BUN (Q1: ≤ 14 mg/dL; Q2:14 < BUN ≤ 19 mg/dL; Q3:19 < BUN ≤ 27 mg/dL; Q4:>27 mg/dL). Multivariable Cox regression, adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, and labs, showed elevated BUN was independently associated with higher 30-day (HR = 1.017, 95% CI: 1.010–1.025), 90-day (HR = 1.014, 1.007–1.021), and 180-day mortality (HR = 1.011, 1.004–1.018). The critically ill AIS patients in the top BUN quartile (> 27 mg/dL) had a nearly 70% higher 30-day, 45% higher 90-day, and 36% higher 180-day mortality risk than those in the bottom quartile, even after full adjustment. Restricted cubic spline analysis demonstrated a linear dose-response relationship between BUN and mortality. Subgroup analysis showed a significant interaction between BUN and CKD: elevated BUN predicted mortality in non-CKD patients but had limited prognostic value in CKD patients. Notably, BUN elevation correlated more strongly with mortality in non-CKD patients. These findings suggest BUN may be an independent predictor useful for risk stratification in critically ill AIS populations, emphasizing its prognostic utility in non-CKD individuals. Further prospective studies are warranted to validate clinical applications and explore underlying mechanisms linking BUN to adverse outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) is a cerebrovascular disease characterized by ischemic necrosis of brain tissue in specific vascular territories caused by stenosis or occlusion of cerebral blood supply arteries, resulting in neurological deficits1. According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study2, stroke remains the second leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide, marked by its high incidence, disability rate, mortality rate, recurrence risk, and significant economic burden. The American Heart Association (AHA)3 reports a 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 10.5% following stroke, with an estimated 7 million stroke-related deaths annually. Given these findings, timely identification of risk factors for poor prognosis in AIS patients is crucial. Accurate prediction of functional outcomes in AIS patients has the potential to significantly enhance clinical management and disease progression.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is a waste product generated by the liver during protein metabolism, excreted by the kidneys, and commonly used in clinical practice alongside creatinine (Cr) to assess renal function4. Both Cr and BUN are filtered by the glomeruli, although BUN undergoes partial reabsorption in the renal tubules. Notably, BUN reabsorption is influenced not only by renal function but also by endocrine activity, making BUN a biomarker of both neurohumoral activation and renal function5. As a crucial indicator reflecting the intricate interplay among nutritional status, protein metabolism, and renal health, BUN serves as a valuable prognostic marker for critically ill patients across various disease conditions6,7. Studies have shown that elevated BUN levels independently increase the risk of mortality in patients with heart failure8. Furthermore, prospective cohort studies suggest that BUN levels show a stronger association with in-hospital mortality in patients with AIS9 and acute coronary syndrome10 compared to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum creatinine (Scr). Collectively, these findings suggest that BUN may serve as an independent predictor of adverse clinical outcomes in AIS patients.

However, the correlation between BUN levels and mortality in critically ill AIS patients remains controversial, with limited evidence available regarding its association with short- and long-term prognoses in this population. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the association between BUN levels measured on the first day of admission and mortality at 30, 90, and 180 days in critically ill AIS patients.

Materials and methods

Population and study design

This study is a retrospective cohort analysis using data extracted from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV v3.0), a publicly accessible database containing deidentified clinical records of patients admitted to the emergency department or intensive care unit (ICU) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston between 2008 and 2022. The dataset includes patient demographics, laboratory results, vital signs, procedures, medications, medical histories, and mortality outcomes. The first author of this study, Liqun Hao, completed the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) program course, passed the certification examination (Record ID: 69115814), and obtained authorization to access the dataset. Given the public availability and deidentified nature of the MIMIC-IV database, neither informed consent nor ethics committee approval was required for this study, in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

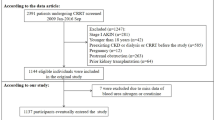

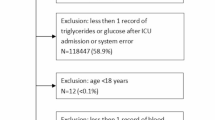

This study included patients diagnosed with AIS based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th revisions (see Supplementary Table S1 online). The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (i) patients with unknown admission or survival times of less than 1 day; (ii) patients under 18 years of age; (iii) patients who were not first-time admissions; and (iv) patients with missing BUN data on the first day of admission. A detailed flowchart outlining the patient selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using R Studio (R version 4.4.2). Demographic data, including gender, age, and medical history (hypertension, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart failure, sepsis, diabetes mellitus, and malignancy), were collected. Comorbidities were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes from discharge records in the MIMIC-IV database. Additionally, laboratory data from the first day of admission, clinical severity scores, treatment modalities, and hospitalization duration were extracted.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of this study was 30-day all-cause mortality, defined as death from any cause occurring within 30 days of ICU admission. Secondary endpoints included 90-day and 180-day all-cause mortality, reflecting deaths within 90 and 180 days of ICU admission, respectively. The 30-day mortality endpoint aligns with the widely accepted neurological standard for evaluating immediate outcomes following acute events, providing insights into the efficacy of initial therapeutic and interventional strategies during the critical early recovery phase. In contrast, the 90-day and 180-day mortality endpoints provide a broader perspective on long-term survival, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of sustained clinical outcomes.

Statistical analysis

In this study, all participants were stratified into four ascending quartiles (Q1–Q4) based on their BUN levels measured on the first day of admission. These were treated as a categorical variable with the following ranges: Q1 (≤ 14 mg/dL), Q2 (14 < BUN ≤ 19 mg/dL), Q3 (19 < BUN ≤ 27 mg/dL), and Q4 ( > 27 mg/dL). Between-group analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare continuous variables, with the results presented as means ± standard deviations. Categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests, and the results were presented as frequencies (percentages). When significant between-group differences were detected, Tukey’s HSD test and Bonferroni’s correction were used respectively to conduct post-hoc pairwise comparisons for continuous variables and categorical variables to identify the specific group pairs that differed significantly. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis compared primary and secondary outcome incidence across BUN quartiles. We separately evaluated the correlation between BUN levels and mortality at 30, 90, and 180 days. For each mortality outcome at each time point, we constructed four progressively adjusted Cox proportional hazards models (Models 1–4). Model 1 was an unadjusted baseline model. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, and body weight to minimize confounding effects. Model 3 further included laboratory parameters (blood glucose, BUN/Scr ratio, partial pressure of oxygen, sodium, potassium, and white blood cell count), while Model 4 expanded adjustments to include comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, acute kidney injury (AKI) and coronary artery disease. P for trend was calculated by treating the BUN quartiles as an ordinal continuous variable in the Cox regression models. This stepwise approach facilitated a comprehensive evaluation of BUN’s prognostic impact across multifactorial contexts. Additionally, a restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis, adjusted for Cox regression model IV, was used to capture any potential dose-response relationship between BUN and all-cause mortality. Finally, subgroup analyses were performed to assess heterogeneity across predefined patient strata. Subgroup analyses employed stratified Cox models with BUN as primary variable. Models were adjusted for glucose, SpO2, serum creatinine, sodium, potassium, WBC, with interaction terms tested for predefined strata: sex, age, and the presence of heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, or CKD. We applied Bonferroni correction for interaction tests. A corrected P value of < 0.007 (0.05/7 subgroups) was considered statistically significant for interaction terms.

R Studio (R version 4.4.2) was utilized for all data analysis. A two-tailed p value below 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline of participants

This study initially identified 4,378 patients with AIS admitted to the ICU. After applying predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3,250 patients were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the process of inclusion and exclusion. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. A detailed assessment of all laboratory parameters, comorbidities, and treatment details across BUN quartiles is presented in Supplementary Table S2. The mean age of participants was 69.24 ± 15.61 years, with 50.37% male. The average BUN level at ICU admission was 24.14 ± 18.52 mg/dL. When stratified by BUN quartiles measured on the first ICU Day, the Q1 group (lowest BUN) exhibited significantly higher mean blood pressure (MBP) and platelet count compared to other quartiles. In contrast, the Q1 group had lower respiratory rate, WBC count, serum creatinine, potassium, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Acute Physiology Score III (APS III), Ongoing Acute Illness Severity (OASIS) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The Q4 group (highest BUN) demonstrated a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as heart failure (HF),, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and hypertension. The Q4 group (highest BUN) demonstrated higher WBC count, ALT, AST, Simplified Acute Physiological Score II (SAPS II), international Normalized Ratio (INR) and a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as heart failure (HF), Coronary heart disease (CHD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), acute kidney injury (AKI), sepsis and Diabetes. Meanwhile, the levels of hemoglobin RBC count, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) were lower compared with the other three groups. The results of pairwise comparisons and post-hoc tests (see Supplementary Table S3-S4 online) confirm that all the above results are statistically significant.

Association between BUN and all-cause mortality

The Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves for the BUN quartiles are shown in Fig. 2. For 30-day all-cause mortality, the KM curves demonstrated a clear diverging trend, and the Log-Rank test confirmed that the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.0001, Fig. 2a). When we performed Cox regression analysis using Q4 as the reference category (see Supplementary Table S5 online), the cumulative survival rate of the highest BUN quartile (Q4) was significantly lower than that of Q1 (P < 0.0001) and Q2 (P < 0.0001), whereas the difference relative to Q3 was not statistically significant (P = 0.069). Consistent with the 30-day findings, the survival curves for each group also differed significantly at 90 days and 180 days (P < 0.0001, Fig. 2b; P < 0.0001, Fig. 2c). Meanwhile, the conclusions drawn from the Cox regression were also consistent with those from the 30-day analysis. To further investigate the effects of BUN on 30-day all-cause mortality, four Cox models were developed (Table 2). These models were adjusted for various factors, including demographic information, laboratory results, and medical history. In Model 4, which included the most comprehensive adjustments, BUN was positively associated with the risk of 30-day mortality in patients with AIS (HR = 1.017, 95% CI: 1.010–1.025). Although the hazard ratio per 1 mg/dL increase appears numerically modest, it signifies a continuous, dose-dependent increase in risk. To contextualize this finding clinically, we calculated the cumulative effect over the interquartile range observed in our cohort. In the fully adjusted model (Model 4), patients in group Q4 had a 69.9% higher risk of 30-day mortality compared to those in group Q1 (HR = 1.699, 95% CI: 1.272–2.269). Similarly, the risk was 41.6% higher in Q3 compared to Q1 (HR = 1.416, 95% CI: 1.094–1.834). Furthermore, BUN was positively associated with the risk of 90- and 180-day mortality in patients with AIS. Moreover, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was used to assess the association between BUN and all-cause mortality in critically ill AIS patients (Fig. 3). The RCS results revealed a linear relationship between BUN and 30-, 90-, and 180-day all-cause mortality in patients with AIS (P-nonlinearity > 0.05).

Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality stratified by admission BUN quartiles. (a) 30-day mortality, (b) 90-day mortality, (c) 180-day mortality. Q1: BUN ≤ 14 mg/dL; Q2: 14 < BUN ≤ 19 mg/dL; Q3: 19 < BUN ≤ 27 mg/dL; Q4: BUN > 27 mg/dL. The number of patients at risk at each time point for each quartile (Q1: n = 941; Q2: n = 814; Q3: n = 741; Q4: n = 754) is shown below the graph. The log-rank test was used to compare overall survival differences, with a P value < 0.0001 for all panels.

Restricted cubic spline plots of the association between BUN levels and all-cause mortality. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. The reference line is set at HR = 1. All three models adjusted for sex, age, weight, glucose, SPO2, serum creatinine, BUN/Scr, sodium, potassium, WBC, CKD, heart failure, Diabetes, Coronary heart disease, Hypertension and AKI, BUN Blood urea nitrogen. The P value for nonlinearity was > 0.05 for all time points, indicating a linear dose-response relationship.

Subgroup analysis

Figure 4 depicts the association between BUN levels and 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day mortality across predefined patient subgroups: sex, age, heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, CKD, and hypertension. The association between elevated BUN levels and increased mortality risk was consistent across all predefined subgroups. After Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (significance threshold set at P < 0.007), a significant interaction effect was observed only for CKD status (interaction P < 0.0001). No significant interactions were detected in the remaining groups (all interactions P > 0.007). This suggests that CKD may reduce the association strength of BUN for mortality outcomes. Extending the analysis to 90-day and 180-day all-cause mortality revealed trends consistent with the 30-day findings, further reinforcing the temporal consistency of BUN’s prognostic value.

Forest plots of subgroup analysis for the correlation between BUN and 30-day(a), 90-day(b) and 180-day(c) all-cause mortality. Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals are shown for each subgroup. Models were adjusted for glucose, SpO2, serum creatinine, sodium, potassium, WBC, with interaction terms tested for predefined strata: sex, age, and the presence of heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, or CKD. CI: Confidence Interval, HR: Hazard Ratio, CKD: chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

This study examined the association between admission BUN levels and 30-, 90-, and 180-day mortality in critically ill AIS patients. Our findings show that elevated BUN levels are significantly associated with increased mortality risk at all three time points. The critically ill AIS patients with admission BUN levels in the top quartile (> 27 mg/dL) faced a nearly 70% increased risk of 30-day mortality, a 45% increased risk of 90-day mortality, and a 36% increased risk of 180-day mortality compared to those in the bottom quartile, even after comprehensive multivariable adjustment. This graded, dose-response relationship across all three time points is highly statistically significant and clinically meaningful. The consistency of this association over both short- and long-term outcomes further reinforces the prognostic value of admission BUN levels in this vulnerable population. Subgroup analyses showed no significant interactions between BUN and mortality except with CKD. The association between elevated BUN and mortality risk was significantly stronger in patients without CKD than in those with CKD (interaction P < 0.001). The reduced risk discrimination of BUN in CKD patients highlights the importance of integrating renal function into clinical decision-making, as BUN elevation in non-CKD populations may necessitate increased clinical vigilance. These findings highlight the potential prognostic value of BUN in critically ill AIS patients and emphasize its potential as a simple, cost-effective biomarker for risk stratification in intensive care settings. While the observational design prevents definitive causal inferences, our results lay the groundwork for future mechanistic studies exploring the pathophysiology underlying BUN-mortality associations, as well as clinical trials evaluating BUN-guided therapeutic interventions in AIS management.

Previous research has shown that BUN acts as an independent prognostic indicator in critically ill patients, strongly correlated with poor outcomes in cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease. Its predictive power exceeds that of traditional renal function markers, such as SCr and eGFR, even after accounting for potential confounders9,11. Kirtane et al.10 reported that in patients with unstable coronary syndromes and normal or mildly reduced eGFR, elevated BUN levels were associated with a 2.2- to 2.7-fold increase in mortality risk, independent of baseline clinical characteristics, renal function, or other biomarkers. Heather et al.12 further validated that BUN levels at admission were a more sensitive short-term prognostic indicator than NT-proBNP in heart failure patients. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study by Liu et al.13 utilizing the MIMIC database, found that higher BUN levels were strongly associated with adverse clinical outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock. Historically, research on the relationship between BUN and outcomes in AIS patients has been limited, with ongoing debate about the prognostic relevance of renal biomarkers14,15,16,17. BUN has often been considered a less specific renal marker than SCr and eGFR. However, recent studies suggest that BUN independently predicts poor prognosis in AIS patients. For example, You et al.9 showed that elevated BUN levels were significantly associated with increased in-hospital mortality. After adjusting for potential confounders (including eGFR), patients with higher BUN levels exhibited a 3.75-fold increased risk of in-hospital death. This association remained significant in subgroup analyses stratified by eGFR. Additionally, a cohort study of 1,866 patients18 found that those in the highest BUN quartile (≥ 19 mg/dL) had a significantly increased risk of 3-month adverse outcomes (p < 0.001). To date, no research has specifically focused on critically ill AIS patients in the ICU. ICU-admitted AIS patients often exhibit increased clinical complexity due to the multifactorial nature of critical illness and comorbidities. Timely identification of high-risk patients with poor prognoses is essential for guiding urgent clinical interventions, optimizing resource allocation, and tailoring personalized therapeutic strategies for this vulnerable population. To address this gap, our study specifically examined critically ill AIS patients in the ICU. We found that elevated BUN levels were consistently associated with increased short- and long-term mortality risks. After adjusting for confounders, patients in higher BUN quartiles (Q3 and Q4) exhibited 1.45-fold and 1.5-fold increases in 30-day mortality risk, respectively. Subgroup analyses confirmed the consistent and significant association between elevated BUN and both short- and long-term mortality across diverse clinical strata.

The exact mechanism linking high BUN levels to poor prognosis in critically ill AIS patients remains unclear. First, elevated BUN on admission may reflect haemodynamic deterioration8, a known predictor of poor stroke prognosis19. Secondly, Cardiovascular complications are key determinants of poor prognosis in patients with AIS20. Renal tubular reabsorption of urea occurs through two distinct mechanisms: concentration-dependent reabsorption in the proximal tubule and arginine vasopressin (AVP)-dependent reabsorption in the collecting duct21,22. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) decreases urinary flow rates, thereby promoting urea reabsorption through concentration-dependent pathways13. Elevated BUN levels post-AIS are strongly associated with sympathetic overactivation23. AIS can induce autonomic dysregulation triggers SNS hyperactivity, which elevates circulating catecholamines and cardiac troponin levels, promotes arrhythmias independently associated with sudden cardiac death, and exacerbates myocardial injury24,25,26. These cascades may result in fatal outcomes or predispose survivors to lifelong cardiac sequelae, adversely affecting both short-term and long-term prognosis27. This further underscores the necessity of close monitoring and implementing cardioprotective interventions in critically ill AIS patients with elevated BUN levels to mitigate cardiac complications and improve clinical outcomes. Additionally, patients with severe cerebral infarction exhibit a stress response during the acute phase that activates the hypothalamic‑pituitary‑adrenal (HPA) axis. This activation leads to an increase in the synthesis and secretion of cortisol28. Cortisol stimulates proteolysis, thereby releasing substantial quantities of amino acids into the bloodstream. Following hepatic uptake, these amino acids undergo transamination, which removes amino groups and subsequently activates the ornithine cycle. This process results in increased urea production, ultimately leading to elevated BUN levels. Studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between serum cortisol concentrations and stroke severity29, suggesting that BUN concentrations are also closely associated with stroke severity. Furthermore, the inflammatory response triggered by cerebral infarction induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines30. These cytokines accelerate muscle protein catabolism and amino-acid release via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway31,32, further contributing to BUN production. In summary, elevated BUN concentrations reflect the severity of cerebral infarction and are associated with adverse outcomes.

Our study has several strengths: first, we observed an association between BUN levels on admission and mortality in critically ill AIS patients at 30, 90, and 180 days. This suggests that BUN levels may serve as an independent risk factor for predicting short- to long-term survival. The results may help clinicians quickly identify high-risk patients and guide clinical decision-making. Our findings support BUN’s role in ICU triage: high level BUN may prompt early interventions, including volume assessment, nutritional support, or neurohormonal modulation. Future trials should test BUN-guided protocols for high-risk AIS patients.

This study has several limitations: first, it used observational data from the MIMIC-IV database, a retrospective analysis conducted at a single medical center, which limits the ability to establish a clear causal relationship. Although we included a large number of patients, further validation through multicenter prospective studies with larger sample sizes and longer time spans is needed. Second, although we adjusted for various variables and conducted subgroup analyses, potential confounders may still influence our findings. Additionally, the laboratory data used in this study were collected on the first day of patients’ admission to the ICU; therefore, we could not analyze the impact of persistent changes in BUN on survival in critically ill AIS patients. Finally, although we observed an association between BUN and mortality across three time periods in this study, we could not establish a direct causal relationship, and the exact mechanism requires further investigation.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that elevated BUN levels are significantly associated with increased 30-day all-cause mortality in critically ill AIS patients. Importantly, subgroup analysis revealed a critical modification by CKD status: the association was substantially stronger in non-CKD patients, whereas BUN’s predictive utility was attenuated in CKD populations. This underscores the potential of BUN as a pragmatic prognostic biomarker, particularly in non-CKD individuals, where it may better inform risk stratification and clinical decision-making. We observed that higher BUN was consistently associated with increased all-cause mortality, and this relationship held for both 90-day and 180-day mortality as well.

Data availability

Data for this study were obtained from the MIMIC-IV database. Available at: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.0/.

References

Walter, K. What is acute ischemic stroke? JAMA 327, 885 (2022).

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20, 795–820 (2021).

Writing Group Members. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133, e38–360 (2016).

Peng, R. et al. Blood urea nitrogen, blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio and incident stroke: the dongfeng-tongji cohort. Atherosclerosis 333, 1–8 (2021).

Arihan, O. et al. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) is independently associated with mortality in critically ill patients admitted to ICU. PLoS ONE. 13, e0191697 (2018).

Faisst, M., Wellner, U. F., Utzolino, S., Hopt, U. T. & Keck, T. Elevated blood urea nitrogen is an independent risk factor of prolonged intensive care unit stay due to acute necrotizing pancreatitis. J. Crit. Care. 25, 105–111 (2010).

Wang, Z. et al. Blood urine nitrogen trajectories of acute pancreatitis patients in intensive care units. JIR Volume. 17, 3449–3458 (2024).

Aronson, D., Mittleman, M. A. & Burger, A. J. Elevated blood urea nitrogen level as a predictor of mortality in patients admitted for decompensated heart failure. Am. J. Med. 116, 466–473 (2004).

You, S. et al. Prognostic significance of blood urea nitrogen in acute ischemic stroke. Circ. J. 82, 572–578 (2018).

Kirtane, A. J. et al. Serum blood urea nitrogen as an independent marker of subsequent mortality among patients with acute coronary syndromes and normal to mildly reduced glomerular filtration rates. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1781–1786 (2005).

Hong, C. et al. Association of blood urea nitrogen with cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality in USA adults: results from NHANES 1999–2006. Nutrients 15, 461 (2023).

Shenkman, H. J., Zareba, W. & Bisognano, J. D. Comparison of prognostic significance of amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide versus blood urea nitrogen for predicting events in patients hospitalized for heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 99, 1143–1145 (2007).

Liu, E. & Zeng, C. Blood urea nitrogen and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with cardiogenic shock: Analysis of the MIMIC‐III database. BioMed. Res. Int. 2021, 5948636 (2021).

Ovbiagele, B. et al. Patterns of care quality and prognosis among hospitalized ischemic stroke patients with chronic kidney disease. JAHA 3, e000905 (2014).

Kumai, Y. et al. Proteinuria and clinical outcomes after ischemic stroke. Neurology 78, 1909–1915 (2012).

Ovbiagele, B. Chronic kidney disease and risk of death during hospitalization for stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 301, 46–50 (2011).

Schrock, J. W., Glasenapp, M. & Drogell, K. Elevated blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio is associated with poor outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 114, 881–884 (2012).

Zhou, P., Liu, R., Wang, F., Hu, H. & Deng, Z. Blood urea nitrogen has a nonlinear association with 3-month outcomes with acute ischemic stroke: A second analysis based on a prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 59, 140–148 (2024).

Baizabal-Carvallo, J. F., Alonso-Juarez, M. & Samson, Y. Clinical deterioration following middle cerebral artery hemodynamic changes after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 23, 254–258 (2014).

Chen, Z. et al. Brain-heart interaction: cardiac complications after stroke. Circ. Res. 121, 451–468 (2017).

Kazory, A. Emergence of blood urea nitrogen as a biomarker of neurohormonal activation in heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 106, 694–700 (2010).

Schrier, R. W. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine: not married in heart failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 1, 2–5 (2008).

Erdur, H. et al. Heart rate on admission independently predicts in-hospital mortality in acute ischemic stroke patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 176, 206–210 (2014).

Li, W., Huang, Q. & Zhan, K. Association of serum blood Urea nitrogen to albumin ratio with in-hospital mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A retrospective cohort study of the eICU database. Balkan Med. J. https://doi.org/10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2024.2024-8-77 (2024).

Colivicchi, F., Bassi, A., Santini, M. & Caltagirone, C. Cardiac autonomic derangement and arrhythmias in right-sided stroke with insular involvement. Stroke 35, 2094–2098 (2004).

Scheitz, J. F., Endres, M., Mochmann, H. C., Audebert, H. J. & Nolte, C. H. Frequency, determinants and outcome of elevated troponin in acute ischemic stroke patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 157, 239–242 (2012).

Fan, X. et al. Stroke related brain–heart crosstalk: Pathophysiology, clinical implications, and underlying mechanisms. Adv. Sci. 11, 2307698 (2024).

Chen, X. G. et al. Longitudinal changes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system are related to the prognosis of stroke. Front. Neurol. 13, 946593 (2022).

Barugh, A. J., Gray, P., Shenkin, S. D., MacLullich, A. M. J. & Mead, G. E. Cortisol levels and the severity and outcomes of acute stroke: A systematic review. J. Neurol. 261, 533–545 (2014).

Cui, P., McCullough, L. D. & Hao, J. Brain to periphery in acute ischemic stroke: mechanisms and clinical significance. Front. Neuroendocr. 63, 100932 (2021).

Chen, F., Fu, J. & Feng, H. IL-6 promotes muscle atrophy by increasing ubiquitin–proteasome degradation of muscle regeneration factors after cerebral infarction in rats. Neuromol Med. 27, 3 (2025).

Kitajima, Y., Yoshioka, K. & Suzuki, N. The ubiquitin–proteasome system in regulation of the skeletal muscle homeostasis and atrophy: from basic science to disorders. J. Physiological Sci. 70, 40 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewer for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by 2023 Jinan Science and Technology Program (Clinical Medicine Science and Technology Innovation Program) (grant number 202328003) and 2022 Annual Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of Shandong Province (grant number Z-2022001).

Funding

Acquisition: Yankui Guo. Conceptualization: Liqun Hao, Xuezhi Chen. Investigation: Fei Li, Yong Yu, Mingkun Li, Zhenhao Chen. Formal analysis: Liqun Hao. Writing – original draft: Liqun Hao. Writing – review & editing: Yankui Guo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Liqun Hao, Xuezhi Chen. Investigation: Fei Li, Yong Yu, Mingkun Li, Zhenhao Chen. Formal analysis: Liqun Hao. Writing – original draft: Liqun Hao. Writing – review & editing: Yankui Guo.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, L., Chen, X., Zhu, L. et al. Association between blood urea nitrogen levels and mortality in critical acute ischemic stroke patients. Sci Rep 15, 42511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26551-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26551-7