Abstract

In deep mining engineering, high-stress roadways frequently experience severe damage, thereby compromising the stability of the surrounding rock. This study investigates the stress-energy evolution in the 31,402 material roadway in Hongqinghe Coal Mine through numerical simulation and field measurement. The study focuses on three critical stages of its whole life cycle: facing the excavation roadway, gob-side entry driving, and mining of the working face. The mechanical behavior of each stage shows significant differences. The results show that while facing the excavation roadway, the primary areas of stress concentration and energy dissipation were observed to be approximately 4 m from the goaf driving heading. As the gob-side entry progresses, the stress distribution within the coal pillar transitions to a bimodal pattern, with most energy dissipation occurring on the gob side. When mining the 31,402 working face, the stress distribution across the coal pillar approaches equilibrium, and the energy dissipation pattern evolves into a bimodal form. A partition control strategy for different stages of roadway surrounding rock is proposed, and the support parameters are determined. Engineering practice demonstrates that this technology can effectively control the deformation of the surrounding rock in roadways.

Similar content being viewed by others

As coal mining depth increases, the surrounding rock of deep roadways is increasingly subjected to high geo-stress, strong mining, and nonlinear deformation processes1,2,3,4. The gob-side entry driving technology, which offers advantages like improving coal resource recovery rates, reducing roadway excavation amounts, and shortening working face preparation times, has been widely applied in coal mining5,6,7,8. However, the superposition of high geo-stress and mining stress intensifies the deformation and failure processes of deep roadways, significantly increasing the difficulty of roadway maintenance9,10. By comprehensively analyzing the mechanical characteristics, it is essential to study the mechanical characteristics of gob-side entry throughout its whole life cycle. Based on these findings, scientific and effective zoning control technology has been proposed to ensure safe and efficient deep mining. A substantial corpus of research has been dedicated to the mechanical properties of deep roadways11. Meng et al.10 analyzed the variation of pore structure and unloading point of damaged rock through experiments. They developed a quantitative evaluation index of rock damage based on porosity evolution, which deepened the understanding of the post-peak mechanical behavior of rock mass. Zhao et al.12 revealed the damage mechanism of ‘micro fracture localization - localized region development through overall instability’ of coal and rock mass through triaxial experiments. Yang et al.13 employed high-precision microseismic detection technology to reveal that the micro-fracturing process is influenced by the tension-shear linkage mechanism, wherein tension assumes a primary role. Intensive fracturing is manifested as an MS event cluster, which can serve as an indicator of the failure boundary. Zhang et al.14 discovered that the strength of rock mass diminishes progressively with an increase in aspect ratio, while the shear angle decreases first and then increases. The macroscopic failure mode gradually changes from the tensile-shear mixed failure mode to the single tensile failure mode. Sun et al.15 studied the biaxial compressive mechanical properties of NPR-anchored rock and Poisson’s ratio-anchored rock under different pre-tightening forces through experiments. They established the strength criterion of prestressed NPR-anchored rock mass. Liao et al.16 revealed that the failure of soft rock began in the proximal region and gradually extended to the distal region through physical model experiments. The failure of the rock exacerbates the deformation of the soft rock. Ma et al.17 constructed the roadway stress model of the non-orthogonal state of ground stress and mining stress. They then deduced the boundary equation of the roadway plastic zone under the action of original rock stress and analyzed the evolution mechanism of the plastic zone of the roadway surrounding rock. Zhao et al.18 established a damage model for the roadway, and pointed out that the damaged surrounding rock with the stress relaxation zone is indicative of excavation damage, and the existence of excavation damage zone can reduce the dynamic stress concentration factor of surrounding rock. In the context of roadway surrounding rock control, traditional support methods mostly adopt a single support form or fixed support parameters3,6,19,20, a limitation that hinders adaptability to the dynamic variations in the mechanical environment throughout the whole life cycle of deep gob-side entry. Yan et al.19 revealed that the stress concentration and bottom angle of the roadway roof are the primary causes of creep failure in soft rock roadway. They proposed a combined support method consisting of ‘anchor net, cable shotcrete - roof, and floor corner bolt grouting - deep and shallow hole grouting - secondary reinforcement support’. This method effectively controls the deformation of the surrounding rock. Ma et al.11 proposed a combined support scheme of ‘primary short hollow grouting anchor cable - secondary long grouting anchor cable or constant resistance large deformation anchor cable’, which fully mobilized the bearing capacity of deep surrounding rock and ensured the long-term stability of the roadway. Xie et al.21 revealed the precursor of roadway surrounding rock failure and the bidirectional cracking mechanism of surrounding rock deformation and stress in Zhaojiaba Mine. They established the anchoring mechanics model of a roadway thick roof and proposed a cross-interface anchoring grouting differential support technology. Jiang et al.22 clarified the surrounding rock stress and the surrounding rock evolution law under different pressure relief parameters. They proposed a comprehensive control method for comprehensive pressure relief and bolting, as well as grouting reinforcement of the surrounding rock in the deep roadway. The feasibility of the method was verified. Li et al.20 proposed a novel collaborative reinforcement technology that integrates the supporting structures of grouting anchor cable and concrete-filled steel tube, and verified the scientificity of the method through application. Tian et al.23 revealed the evolution law of the physical and mechanical properties of the strong wind oxidation zone, and proposed a coupling support scheme of ‘pre-grouting - anchor net and shotcrete - inverted arch structure - U-shaped steel - high and low pressure, deep and shallow hole reinforcement grouting’. Qiang et al.24 clarified the stress field direction effect of non-uniform expansion of plastic zone, and revealed the damage mechanism of non-uniform deformation of inclined coal seam.In summary, the mechanical characteristics and control technology of deep gob-side entry have been extensively studied, and significant progress has been made. However, most of the research mainly concentrates on the mechanism and control technology of a single stage, with comparatively few studies addressing the whole life cycle of the roadway. Taking Hongqinghe Coal Mine as a case study, this paper studies the mechanical characteristics and zoning control technology of the whole life cycle of the gob-side entry. The service process of gob-side entry consists of three distinct stages: facing the excavation roadway, gob-side entry driving, and mining of the working face. A three-dimensional numerical calculation model was constructed to study the evolution law of the stress and energy field in different stages of the roadway. On this basis, the partition control technology of surrounding rock in deep gob-side entry is proposed, and the rationality of the control technology is verified by field application, which provides a theoretical basis for the stability control of deep gob-side entry.

Engineering background

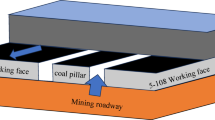

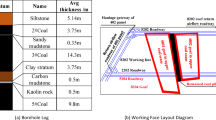

The Hongqinghe Coal Mine is located in the Zhalaite Banner of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, within the Xinjie Mining Area of the Dongsheng Coal Field. The mining area of the mine is 140.76 km2, with designed recoverable reserves of 21.69 billion tons. Based on the management regulations of the rock burst mine, the production capacity is 8 million t/a, as shown in Fig. 1 (b). The main coal seam of the coal mine is the 3 − 1 coal seam, which has an average buried depth of 718.6 m, a thickness of 6.14 m, and a dip angle of 3°, thus classifying it as nearly horizontal. In the mining process, a large mining height is employed, with heights reaching up to 6 m. The lithology of the roof of the coal seam is primarily composed of sandy mudstone and medium-grained sandstone, while the lithology of the floor is mainly sandy mudstone and mudstone. The histogram of the rock layer is shown in Fig. 1 (c).

The 31,402 working face is situated in the 4th mining area of the 3 − 1 coal seam. The southeast side is the 31,401 gob, while the southwest side is the auxiliary transportation roadway in the north wing. The northeast direction of the cutting hole of the working face is the coal pillar, which is located approximately 50 m from the boundary of the minefield25. The coal pillar size between the 31,402 working face and adjacent areas is 5 m, and the roadway size is 5.4 m (width) × 3.6 m (height).

The dip length of the working face is 245.75 m, the strike length is 3,615.7 m, and the total area is 888,558 m2. The spatial layout is shown in Fig. 1 (a). During the process of the roadway excavation, a total of 15 faults were observed in the working face. Of these faults, eight were exposed in the auxiliary transportation roadway and the open cut, six were exposed in the transportation roadway, and one fault was exposed in the inclined joint roadway of the 31,402 working face.

(a) Layout diagram of 31,402 working face; (b) Satellite map of Hongqinghe coal mine location; and (c) Rock stratum histogram. The satellite map is sourced from the Geographic Information Public Service Platform of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (https://neimenggu.tianditu.gov.cn/chifeng/). It has been further edited using Microsoft Office PowerPoint Home and Student Edition 2021 (https://officecdn.microsoft.com/).

Mechanical analysis of the whole life cycle of gob-side entry

Division of service stage of gob-side entry

The whole life cycle of gob-side entry comprises three stages: facing the excavation roadway, the gob-side entry driving, and the mining of the working face26. The stress-dominant factors of the surrounding rock and the structural characteristics of the overlying rock it is divided into three stages, as shown in Fig. 2.

Stage Ⅰ (facing the excavation roadway stage): the previous working face has not been mined out, and the roadway is driving from the boundary of the mining area to the working face, which is opposite to the mining direction of the previous working face. The spacing is progressively diminished. The previous working face is in the normal mining stage, and the overlying rock forms a dynamic evolution structure of ‘cantilever beam-masonry beam’ based on the theory of ‘masonry beam’. However, a stable structure has not yet been formed, and the roadway is located within the influence range of the advanced support stress of the working face.

Stage Ⅱ (gob-side entry driving stage): At the end of the mining of the previous working face, the overburden within the goaf gradually stabilizes, and the roadway is excavated along the edge of the goaf27. The process is influenced by the lateral abutment pressure of the hinged structure, such as the cantilever and the masonry beams on the side of the goaf. At the end of the mining of the previous working face, the overlying rock in the goaf gradually stabilized, forming a combined structure of a ‘low cantilever beam-high hinged rock block’28,29. The low cantilever beam transmits the load to the shallow rock mass of the surrounding rock of the roadway through its bending deformation. The high-hinged rock blocks transfer the horizontal force to each other through the hinge point of the rock block to the coal body of the roadway, forming a stable lateral abutment pressure distribution.

Stage III (mining stage of the working face): The material roadway of the working face is affected by the two-way dynamic superposition of the advance abutment stress of the working face and the residual stress of the goaf of the previous working face. The surrounding rock of the roadway has undergone the influence of overburden structure evolution, including the initial collapse of the immediate roof and the periodic weighting of the main roof.

Analysis of mechanical behavior of roadway in different service stages

Facing the excavation roadway stage

During the mining process of the previous working face, the excavation of the coal body disrupted the stress balance of the underlying rock, resulting in the transfer of the stress of the overlying rock to the deep coal body, forming the advanced abutment pressure, as shown in Fig. 3. As the mining operation progresses, the stress concentration area is progressively transferred to the deeper regions of the coal body. Consequently, the roadway affected by mining undergoes a process of stress dynamic adjustment. During the excavation stage, the stress balance of the original rock is disrupted, resulting in a transformation of the coal body surrounding the roadway from a three-way force to a two-way force30. The shallow coal body exerts a pressure relief effect due to stress release, while the deep coal body bears the load transferred from the overlying strata, forming stress concentration. The advanced abutment pressure shows a dynamic evolution with the mining of the working face. The specific calculation is as follows:

where σ0 is the original rock stress, k is the stress concentration factor, x is the spatial location coordinates, v is the mining speed of the working face, t is the time variable, xp is the initial offset of the peak stress location, and a is the half-width of the stress decay.

The superposition of the advanced abutment pressure and the roadway excavation disturbance stress leads to the complex and changeable stress evolution of the two sides of the roadway. The shallow coal body enters the plastic softening stage due to pressure relief, resulting in the development of internal cracks and a decrease in bearing capacity. In contrast to the shallow coal body, the deep coal body enters the elastic strengthening stage due to stress concentration, forming a bearing structure of ‘loose outside and tight inside’. This stress redistribution is continuously strengthened with the mining of the working face, which is manifested by the acceleration of the deformation rate of the roadway and the increasing load of the supporting structure. The radius of the plastic zone, R, is determined by the Mohr-Coulomb criterion and strain-softening theory31.

where r0 is the equivalent radius of roadway, c0 and φ0 are the peak cohesion and internal friction angle of coal, respectively, cr and φr are the residual cohesion and internal friction angle of coal, respectively. It can be seen from the above formula that the radius R of the plastic zone increases in proportion to the increase in the advanced bearing pressure. The faster the mining speed of the working face, the faster the expansion rate of the plastic zone.

Gob-side entry driving stage

In the stage of gob-side entry driving, the previous working face has been mined out, and the overlying rock in the goaf forms a stable combination structure of ‘low cantilever beam - high hinged rock block’, as shown in Fig. 4. The cantilever beam is formed by the hanging of the low immediate roof due to the exposure of the goaf. The formula for calculating the bending stress in the middle of the span is as follows32:

where σb is the uniaxial compressive strength of coal-rock mass, MPa, L is the span of the cantilever beam, m, h is the thickness of the cantilever beam, m, Hd is the thickness of the low immediate roof, m, and γ is the bulk density of rock mass, kN/m3. It can be seen from the above formula that the bending stress of the rock beam increases exponentially with the increase of the cantilever length of the rock beam. When the stress value exceeds the strength of the rock mass, the immediate roof begins to collapse periodically.

The strength of the main roof is high, and the hinged rock block is formed after the fracture. The transmission of horizontal thrust and vertical pressure through the hinge fulcrum between the rock blocks results in the formation of a three-hinged arch balance structure. The structural stability of overlying strata is contingent upon the friction between the rock and the hinge angle, as well as the strength of the rock. This combination satisfies the static equilibrium condition, which is expressed as follows:

where Gm is the weight of the rock, △h is the distance between rock blocks, and L is the length of the rock. Bring FAn=FCn=F into the third formula, and the horizontal force \({F_h}=\frac{{{G_m} \cdot \Delta h}}{{2L}}\) can be obtained. The force is transmitted to the coal body of the roadway through the hinge point of the rock mass, forming a stable lateral abutment pressure.

The essence of lateral abutment stress is the transfer of overburden structure load to the coal roadway side. The low cantilever beam transmits the load to the shallow part of the roadway through bending deformation, forming local stress concentration. The horizontal stress exerted by the high-hinged rock mass exerts an effect on the deep part of the roadway, facilitating long-distance stress transfer. After the superposition of the two, the coal body of the roadway is subjected to the coupling stress of ‘shallow bending load-deep horizontal force’, which leads to the failure characteristics of ‘shallow crushing and deep bearing’.

Mining stage of the working face

During the mining process, the roadway is subject to the two-way pressure coupling that is formed by the advanced bearing pressure and the residual stress of the working face. The front of the roadway is affected by the advanced abutment pressure of the working face, and the rear is affected by the residual stress of the previous working face33. The advanced abutment pressure increases initially and subsequently stabilizes as the working face is mined. The peak position is situated within the range of 10–30 m in front of the working face, which is the result of the transfer of the self-weight of the overlying strata to the interior of the solid coal. The residual stress is distributed within the range of 5–20 m at the edge of the goaf. The combination of these factors results in the formation of a stress superposition area within the roadway, and the superimposed coupling stress peak, xpeak, satisfies the following equation:

where \({x_{adv}}\) is the distance between the peak value of advance abutment pressure and the working face, and \({x_{res}}\) is the distance from the peak value of residual stress to the goaf.

When the periodic pressure is applied, the dynamic pressure caused by the fracture of the main roof further exacerbates the change of stress. The load mutation caused by the fracture of the main roof exhibits transient and periodic characteristics, which leads to the dynamic impact of the roadway support structure. The magnitude of dynamic pressure is positively correlated with the thickness and hanging area of the main roof. The frequency of dynamic pressure is directly proportional to the mining speed of the working face and inversely proportional to the periodic weighting step of the main roof. The dynamic load effect has been shown to expand the stress difference of the surrounding rock, exacerbate the penetration of cracks in the rock layer, and promote the surrounding rock to change from static shear failure to dynamic impact failure.

During the mining processes, the peak value of the advanced abutment pressure is continuously transferred to the deeper part of the coal body, and the residual stress is distributed statically due to the stability of the overburden structure of the previous working face. The superposition effect of the two is not a simple spatial superposition, but a dynamic process affected by many factors, such as the mining speed of the working face, the mechanical properties of the rock strata, and the geological structure.

Numerical simulation of stress-energy evolution in the whole life cycle of roadway

Establishment of the numerical model

A three-dimensional numerical model was constructed to investigate the vertical stress and strain energy evolution throughout the service cycle of the surrounding rock in deep roadways. The model is based on the layout relationship between the 31,401 and 31,402 working faces at the Hongqinghe Coal Mine, as shown in Fig. 5. The model’s dimensions are 250 m in dip, 400 m in strike, and 186 m in height. The model comprises 1,323,600 mesh elements and 1,367,202 nodes. Incorporating the 31,401 and 31,402 working faces and their corresponding roadways ensures comprehensive simulation experiments.

In the numerical model, the bottom boundary constrains vertical displacement, while the lateral boundaries are constrained to limit horizontal movement, thereby ensuring stability during the simulation. The top boundary is designed as a free boundary, thereby stimulating the self-weight of the overlying rock. This is accomplished by applying a vertical load of 18 MPa to the top boundary. A lateral pressure coefficient of 1.2, derived from in-situ stress measurements, is applied to the model to simulate horizontal stress conditions. The mechanical properties of the coal and rock layers are shown in Table 1.

Three-dimensional numerical model. The 3D images were created by FLAC3D 7.0, https://www.itasca.com/.

Simulation results and discussion

The stability of the 31,402 material roadway was influenced by three critical stages: the facing excavation roadway stage, the gob-side entry driving stage, and the mining stage of the 31,402 working face. This section employs numerical simulation to investigate the vertical stress and strain energy evolution within the surrounding rock throughout the service cycle of deep roadways.

Facing the excavation roadway stage

The intersection of the excavation at the 31,401 working face with the 31,402 material roadway results in an altered stress distribution within the surrounding rock of the mining area, as shown in Fig. 6 (a). The mining of the 31,401 working face leads to a local stress concentration zone in the surrounding rock, and the maximum stress value is 40 MPa. The lack of significant energy accumulation at this stage results from the combined effects of stress redistribution and energy dissipation during interactions. The 31,401 mining operation initially stores strain energy; however, subsequent rock deformation and stress re-equilibration facilitate energy release. In contrast, standalone roadway excavation or continuous mining maintains stress concentration for a longer duration, thereby promoting energy accumulation before complete dissipation. A monitoring section has been arranged at the intersection of the advancing and excavated zones to monitor the distribution characteristics of dissipated energy in the surrounding rock during the excavation stage, as shown in Fig. 6 (b). Negative values are indicative of energy accumulation. Conversely, positive values indicate energy dissipation, thereby signifying the failure mechanism of the surrounding rock.

An energy dissipation zone, measuring up to 4 m wide, is observed on the side of the coal pillar adjacent to the goaf, with a maximum dissipation density reaching 50 kJ/m³. A similar energy dissipation zone was observed on the roadway side of the 31,402 material roadway, also near the goaf, exhibiting an energy dissipation value of approximately 46 kJ/m³. The energy distribution within the coal pillar is uneven, with dissipation areas near the goaf and the roadway contrasting with regions of relative energy accumulation in other parts of the pillar. This uneven distribution can be attributed to the excavation of the 31,402 material roadway, which initiates a transition in the surrounding rock’s stability from an unstable to a stable condition. During this process, the stored strain energy is progressively released, thereby causing damage to the rock structure surrounding the roadway. In contrast, the deeper sections of the coal pillar, being more distant from the active mining zone, primarily exhibit an energy state characterized by the accumulation of deformation energy, with no significant energy dissipation occurring.

Vertical stress and strain energy distribution of the surrounding rock at the intersection of the entry and mining areas. The 3D images were created by Tecplot 360 EX 2023 R1, https://www.tecplot.com/. (a) Vertical stress, (b) Dissipation energy.

A measuring line has been established to monitor the vertical stress distribution within the coal pillars at the intersection with the advancing mining face. The line above records stress data under two distinct conditions: initially, when the mining face is in proximity to the measurement point (when it is approaching the working face), and subsequently, once it has moved past the measurement point (after passing through the working face). The distribution of stress is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows the vertical stress distribution of the coal pillar when the 31,402 material roadway is adjacent to the 31,401 working face. It shows that the maximum lateral abutment pressure occurs at a distance of 4 m from the edge of the coal pillar. This corresponds to a peak stress value of approximately 29.35 MPa and a stress concentration factor of 1.63. Upon entering the gob-side entry driving stage, the coal pillar undergoes a secondary disturbance, particularly on the side near the gob area. Consequently, the stress value increases to 38.66 MPa, with a stress concentration factor of 2.15. The position of the vertical stress peak in the coal pillar remains constant and is situated within 5 m of the coal pillar’s edge.

Gob-side entry driving stage.

Vertical stress and strain energy evolution distribution after roadway excavation. The 3D images were created by Tecplot 360 EX 2023 R1, https://www.tecplot.com/. (a) Vertical stress − 100 m, (b) Vertical stress − 200 m, (c) Dissipated energy distribution − 100 m, (d) Dissipated energy distribution − 200 m.

Figure 8 shows a comparative analysis of the vertical stress and energy dissipation patterns in the surrounding rock at various stages of the roadway excavation process within the goaf.

When the 31,402 material roadway advances 100 m in proximity to the goaf, the surrounding rock experiences a redistribution of stress. It tends to be stable, resulting in a more uniform stress distribution across the coal pillar sections. The internal stress within the coal pillar displayed a bimodal pattern, with significant stress peaks of approximately 36.77 MPa on the side closest to the goaf. Concurrently, the energy accumulation within the pillar has remained stable at 56.4 kJ/m³, indicating a dynamic equilibrium between internal stress and stored energy.

As excavation of the roadway extends 200 m towards the goaf, the peak stress on the adjacent side of the coal pillar increases to 40.38 MPa. This sharp rise in stress concentration accelerates the expansion and damage to internal cracks in coal, resulting in enhanced damage. The damage evolution process, which includes crack growth and mechanical property deterioration, is exacerbated. As a result, the probability of extensive and localized pillar failures is increased, endangering the stability of the roadway.

The stress measurement lines within the model have been positioned at a distance of y = 130 m to quantify the vertical stress in the surrounding rock. These lines reflect the rock’s stress response as the excavation distance along the 31,402 material roadway changes, as shown in Fig. 9.

The roadway excavation adjacent to the 31,402 goaf exerts negligible influence on the stress distribution within the coal pillar. The internal stress within the pillar exhibits a bimodal distribution, with a more pronounced peak in the vicinity of the goaf and a less pronounced one in the proximity of the roadway. This distribution results in higher stress values in the vicinity of the goaf, with a stress concentration factor of approximately 2.1, compared to the lower values observed in the proximity of the roadway, which is estimated to be around 1.5. As the excavation of the roadway progresses, the stress values on the sides of the coal pillar exhibit a notable increase. As measured at various excavation distances, the stress distribution curves for the 31,402 working face exhibit a uniform trend with a stress concentration factor of approximately 1.67.

The excavation of the roadway has a significant impact on the vertical stress distribution and strain energy storage within the coal pillar, which may potentially lead to instability of the surrounding rock. It is therefore imperative to maintain continuous monitoring of the adjacent stress distribution throughout the excavation process to prevent any potential roadway instability.

Mining stage of the 31,402 working face

Figure 10 shows the vertical stress and dissipated energy distribution for the extraction stages at the 31,402 working face, which are 100 m, 200 m, and 300 m, respectively. During the mining process of the 31,402 working face, the vertical stress distribution within the coal pillar shifts from a left-biased pattern to a balanced distribution. The maximum stress within the coal pillar, reaching 53.1 MPa, becomes concentrated at the interface with the adjacent 31,401 goaf, indicating a critical stress concentration zone.

A monitoring section was set at a distance of y = 130 m within the model to investigate the energy dissipation in the surrounding rock during the mining process of the 31,402 working face. This section was designed to record the distribution of dissipated energy, as seen in Fig. 10 (b), (d), and (f). The data show that energy dissipation is concentrated on the side near the 31,401 goaf, which is influenced by the dimensions of the coal pillar. Following the completion of extraction on both sides of the pillar behind the 31,402 working face, the dissipated energy distribution transitions to a bimodal pattern, with peaks in energy concentration about 2.5–4 m from the goaf. This bimodal pattern, characterized by two distinct energy peaks, indicates high internal deformation energy within the coal pillar, which poses a significant risk of damage to the weak planes within its structure.

Vertical stress and strain energy distribution in the mining process of the 3402 working face. The 3D images were created by Tecplot 360 EX 2023 R1, https://www.tecplot.com/. .

Partition control technology of surrounding rock in gob-side entry

Control system of roadway surrounding rock

The 31,402 material roadway is divided into three distinct phases based on the service process and the vertical stress and strain energy evolution of the surrounding rocks. These phases are the facing excavation roadway stage, the gob-side entry driving stage, and the mining stage of the 31,402 working face. Considering the disparate stress conditions in each phase, a partition control strategy for the surrounding rock is proposed, as shown in Fig. 11.

Support technology of surrounding rock in gob-side entry

Considering the results of numerical simulation, the results of engineering analogy, and the special conditions of the site, the corresponding control parameters are formulated to realize the stability control of the surrounding rock throughout the mining roadway’s service period. The control parameters of different stages are shown in Fig. 12.

(1) Facing excavation roadway stage: To effectively resist the excavation disturbance of the 31,401 working face and the advanced abutment pressure generated by future mining activities, an enhanced surrounding rock support strategy is adopted for the driving heading for mining of the working face. The rhombus mesh is employed to reinforce the surrounding rock of the roadway. The overlapping distance between the rhombus metal mesh must be a minimum of 100 mm, the overlapping distance between the top mesh and the side mesh must be a minimum of 500 mm, and a bolt must be set up at each shoulder socket of the roadway. Ultimately, three W-shaped longitudinal steel belts and anchor cables reinforce the roof.

(2) Gob-side entry driving stage: Due to the influence of roof collapse and stress redistribution in the goaf, the roof pressure and support difficulty increase. The roof adopts a high-strength and high-density bolt support scheme. Each row is arranged with 6 high-strength bolts of 2.4 m, and the row spacing is 900 mm × 900 mm. At the same time, the steel mesh, diamond metal mesh, and W-shaped steel belt are combined to protect the roof. In terms of anchor cables, three 6.3-meter anchor cables are arranged in each row, with an interval of 800 mm × 1800 mm.

(3) Mining stage of the working face: The roadway is affected by the mining of the 31,402 working face, and the stress environment becomes more complex and changeable, which requires the support system to have higher adaptability and stability. The roof support adopts 8 high-strength bolts of 2.4 m, of which the row spacing of the four anchor cables is 800 mm × 800 mm, and the row spacing of the other four is 700 mm × 800 mm, and cooperates with 3 high-strength prestressed anchor cables of 8.5 m. Among them, the middle anchor cable is arranged perpendicular to the roadway’s roof; the other two are kept at an angle of 15° with the vertical line, and the row spacing is 1200 mm × 1800 mm.

Field experiment and result analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of support schemes at various stages of mining, monitoring stations have been established in critical areas, including facing the excavation roadway, gob-side entry driving, and the mining stage of the working face. The deformation of the surrounding rock at different mining stages is monitored using the cross-measuring point method. By analyzing the data collected from these measuring points, a surface displacement curve of the roadway, as shown in Fig. 13, has been generated, with a monitoring period of 60 days.

As shown in Fig. 13, during the initial 10 days of both the facing the working face mining and working face mining phases, significant surface deformation of the surrounding rock in the roadway was observed. After the initial 10 days, the deformation rate in the surrounding rock progressively diminished and achieved stability around 30 days. In the gob-side entry excavation phase, a rapid increase in the deformation of the surrounding rock occurred within the first 15 days. After that, the deformation rate experienced a gradual reduction and reached stability after approximately 40 days. The roadway control measures were effective, meeting standard production requirements. The deformation magnitude of the roadway followed the order: the facing excavation roadway stage > the mining stage of the 31,402 working face > the gob-side entry driving stage.

Conclusion

In this paper, based on the combination of numerical simulation and field monitoring, the evolution of the vertical stress and strain energy in the service cycle of the gob-side roadway is studied, and the partition control strategy is proposed. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The research elucidates the differences in mechanical mechanisms and the evolution of stress throughout the three stages of the gob-side entry life cycle. During the facing excavation roadway stage, the surrounding rock is dynamically influenced by the advanced abutment stress from the front working face. In the gob-side entry driving stage, the overburden in the goaf forms a stable structure characterized as a cantilever beam-high hinged rock block, its lateral abutment pressure serving as the primary stress source for the surrounding rock of the roadway. In the mining stage of the working face, the surrounding rock experiences the coupling effect of the abutment pressure from the front working face and the residual stress present in the goaf.

(2) During gob-side entry driving, the primary stress concentration and energy dissipation zone within the coal pillar is located approximately 4 m from the goaf. As excavation proceeds, the stress distribution evolves from an initially asymmetric profile (with higher stress on the goaf side and lower stress on the solid coal side) into a balanced, bimodal pattern. Throughout the mining of the 31,402 working face, the stress in the coal pillar ultimately stabilizes into this bimodal distribution, with peak energy dissipation occurring 2.5 to 4 m from the goaf.

(3) Based on the distribution characteristics of vertical stress and strain energy in the 31,402 material roadway, it can be divided into three stages: the facing excavation roadway, the gob-side entry driving, and the mining of the working face. A partition control strategy for the surrounding rock of the roadway is proposed according to the characteristics of each stage, along with the establishment of corresponding support parameters. Engineering practice demonstrates that this technology can effectively inhibit the deformation of the surrounding rock and enhance overall stability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xie, S. et al. Research on the control technology and key parameters of external anchor-internal unloading of surrounding rock during gob-side entry driving under severe mining of 1000-m-deep mine. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57, 2913–2932 (2024).

Hou, C. J., Wang, X. Y., Bai, J. B., Meng, N. K. & Wu, W. D. Basic theory and technology study of stability control for surrounding rock in deep roadway. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 50, 1–12 (2021).

Xiao, T. Q. et al. Study on the mechanism and technology of floor heave control of deep roadway with strong mining pressure. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 41, 666–676 (2024).

Guoning, Z., Yongjiang, Y. & Wei, Z. Experimental investigation of the acoustic emission and energy evolution of bedded coal under uniaxial compression. Sci. Rep. 15, 12578 (2025).

Tian, Z., Zhang, Z., Deng, M., Yan, S. & Bai, J. Gob-Side entry retained with soft Roof, Floor, and seam in thin coal seams: A case study. Sustainability 12, 1197 (2020).

Ma, L. et al. Research on the instability mechanism and control technology of Gob-Side entry in deep mines with soft rock. BUILDINGS-BASEL 15, 19 (2025).

Li, L. et al. The entry retained along gob side with small coal pillar and its surrounding rock control: a case study. Sci. Rep. 14, 28081 (2024).

Huang, W., Jing, G., Ma, L., Zhao, L. & Wang, S. Research on blasting technology for Thick and hard roof fracturing in isolated Island coal mine working face. Sci. Rep. 15, 14534 (2025).

Yang, S., Ning, J., Zhang, X., Wang, J. & Shi, X. Analysis of stress environment and deformation failure of surrounding rock in deep roadway after pressure relief: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 160, 108173 (2024).

Meng, Q. et al. Experimental study on the macroscopic and mesoscopic mechanical characteristics of deep damaged and fractured rock. Eng. Fract. Mech. 310, 110529 (2024).

Ma, Z. et al. Instability mechanism and control technology of soft rock roadways affected by mining in karst mountain area. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 10, 22 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. Acoustic emission and failure characteristics of coal and rock under single-free-face true triaxial loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108299 (2024).

Yang, K., Chen, C., Xia, K., Wang, T. & Sun, Y. Stability analysis and failure mechanism of the hanging wall in a sublevel caving mine based on microseismic monitoring. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 259 (2024).

Zhang, W., Qiu, Z., Liu, W., Zhang, B. & Guo, W. Study on the AE characteristics and energy evolution mechanism of sandstone with different aspect ratios under biaxial compression. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 57, 9019–9034 (2024).

Sun, X., Wang, L., Cui, L., Zhang, Y. & Jiang, M. Experimental investigation of biaxial compressive mechanical property of NPR anchored rock with different preload forces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 146, 105621 (2024).

Liao, P., Wang, F. & Guo, C. Experimental analysis on the progressive failure mechanism of soft rock subjected to tunnel excavation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 164, 108636 (2024).

Ma, Z., Zuo, J., Zhu, F., Liu, H. & Xu, C. Non-orthogonal failure behavior of roadway surrounding rock subjected to deep complicated stress. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56, 6261–6283 (2023).

Zhao, H., Tao, M. & Li, X. Theoretical analysis of dynamic stress distribution around a circular damaged roadway under transient disturbance. Num Anal. Meth Geomech. 47, 3248–3265 (2023).

Yan, L. et al. Creep deformation characteristics and control technology in deep mine soft rock roadway. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 10, 144 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Failure mechanisms and reinforcement support of soft rock roadway in deep extra-thick coal seam: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 165, 108745 (2024).

Xie, Z. et al. Study on Time-Dependent failure mechanisms and CBAG differential support technology of roadway in steeply inclined coal seam. Processes 11, 866 (2023).

Jiang, Z. et al. Research on cooperative control method of comprehensive pressure relief and anchor grouting reinforcement in deep mining roadways. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ Geo-resour. 10, 79 (2024).

Tian, M., Gao, X., Zhang, A., Han, L. & Xiao, H. Study on the deformation failure mechanism and coupling support technology of soft rock roadways in strong wind oxidation zones. Eng. Fail. Anal. 156, 107840 (2024).

Qiang, X. et al. Nonuniform deformation instability mechanism of Gob-Side entry retained in inclined coal seam and stability control. Appl. Sci. 13, 8727 (2023).

Li, Y., Li, G., Xu, S. & Wu, D. The spatial-temporal evolution law of microseismic activities in the failure process of deep rock masses. J. Appl. Geophys. 154, 1–10 (2018).

Chen, D. C. et al. The full cycle evolution law of energy-stress in the surrounding rock of the gob-side entry driving for adjacent advancing working face. Coal Sci. Technol. 4, 162–175 (2025).

Wang, J., Liu, P., He, M., Yu, G. & Tian, H. Floor heave mechanism for gob-side entry retaining with concrete blocks and control method: A case study. Undergr. Space. 15, 244–259 (2024).

Pan, G. Q. Study on Stability Mechanism and Control Technology of Roadway Surrounding Rock Top Coal Caving Longwall Mining of extra-thick Coal Seam (China University of Mining & Technology, 2023).

Zhao, Y., Yang, Y., Li, X. & Wang, Z. Overlying strata movement and abutment pressure evolution process of fully mechanized top coal caving mining in extra thick coal seam. Geofluids 2021(1), 7839888 (2021).

Fu, Q. et al. Combined blasting for protection of gob-side roadway with Thick and hard roof. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16, 3165–3180 (2024).

Xu, Z. Calculation of radius of plastic zone in surrounding rock of roadway. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 781, 022106 (2021).

Gustavo Berni. Equation for the simplified calculation of the horizontal shear stress in composite beams of rectangular cross-section with considerable width. Electron. J. Struct. Eng. 24, 8–13 (2024).

Lv, J. et al. Failure characteristics and stability control technology of dynamic pressure roadway affected by the mining activity: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 131, 105857 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 52174121].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. H.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation. H. J.: Methodology, Resources, Supervision. L. J. and Z. L.: Writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, H., Hao, J., Lv, J. et al. Mechanical characteristics and partition control technology in whole life cycle of deep gob-side entry: A case study. Sci Rep 15, 39067 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26593-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26593-x