Abstract

In this paper, we present an inverse design framework based on the finite element method (FEM) tailored for 4D printed structures capable of undergoing programmable, stimulus-responsive shape transformations over time. In contrast to conventional forward simulations, which predict deformation from a given initial configuration, our inverse approach seeks to determine the required printed geometry that will evolve into a desired final shape under specific external stimuli. The proposed framework incorporates viscoelasticity, geometric nonlinearity and time-dependent behavior into the FEM solver, formulating the inverse design task as an optimization problem. It enables users to specify custom target shapes and boundary conditions, thereby providing the flexibility needed to address a wide range of design scenarios. A comprehensive implementation workflow of the framework is also presented. To demonstrate the versatility and feasibility of our approach, we present two representative case studies: a classic bilayer actuator with 4D-printed normal hydrogel and a soft gripper with electrically responsive hydrogel. The results confirm the framework’s accuracy and adaptability to different external stimulus, highlighting its potential as a practical computational design tool for the inverse design of 4D printed structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

4D printing, an extension of additive manufacturing that incorporates the dimension of time, has emerged as a powerful tool for fabricating stimuli-responsive structures capable of shape-morphing behaviors1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. By integrating smart materials such as shape memory polymers9,10,11, hydrogels12,13,14, and liquid crystal elastomers15,16,17,18 into spatially programmed architectures, 4D printed structures can undergo complex deformations in response to external stimuli including heat, light, humidity, electric or magnet fields19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. This capability has opened new avenues in the design of reconfigurable devices, adaptive structures, and especially soft robotics, where compliance and adaptability are critical30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Among them, 4D printed actuators offer an attractive route to achieve programmable motion without traditional mechanical components, enabling compact, integrated designs with high functional density37,38,39. As the field evolves, a major focus lies in developing computational design tools that can effectively guide the design of such structures toward desired functionalities.

Despite the increasing capability of 4D printing to produce complex, responsive structures, a central challenge remains: how to design printed structures that achieve a desired deformation or functional shape under specific external stimuli. This challenge naturally leads to the formulation of inverse design problems, where the target output, typically a final shape, is prescribed7,30. Recent studies have begun to develop different modeling methods and inverse design approaches for 4D printing to achieve targeted shape transformations. Momeni et al. laid a theoretical foundation by deriving general laws of 4D printing, a bi-exponential analytical model capturing time-dependent deformation behavior (curvature evolution over time) in stimuli-responsive multi-material structures19. This model introduces two distinct time constants to predict shape-morphing responses across various active materials. To facilitate practical design, Kwok and Chen developed a geometry-driven finite element (GDFE) framework to simulate and design 4D printed self-folding structures40. In this method, the relationship between a component’s geometry and its resulting bending angle is extracted from a few experiments and embedded into customized finite elements, enabling efficient prediction of final shapes without a full physics model. Furthermore, Wang et al. introduced 4DMesh, an end-to-end inverse design pipeline that combines thermoplastic actuators with geometric algorithms, enabling flat sheets to transform into non-developable 3D surfaces directly from CAD models, with applications ranging from furniture to wearables41. Similarly, An et al. proposed Thermorph, a self-folding method using commodity thermoplastics and desktop FDM printers, which compiles 3D models into 2D foldable patterns and achieves intricate self-folded structures such as roses, boats, and armor with significant gains in printing efficiency42. Most recently, Wang et al. proposed an inverse design strategy tailored to microscale 4D printing of soft micromachines, combining analytical and algorithmic tools to achieve customized bending deformations43. Their approach uses a piecewise constant-curvature approximation and the Timoshenko bilayer bending model to determine the spatial distribution of active “muscle” and passive “skeleton” material that yields specified curvature and bending angles under stimulus. This strategy enabled the fabrication of biomimetic micro-structures with complex shape-morphing (e.g., multi-segment bending in a dragon-inspired microrobot and an inchworm-like crawler).

Additionally, in recent years, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising tool to tackle the inverse design problem of 4D printed structures. A common strategy involves combining ML with evolutionary algorithms (EA) to optimize the distribution of active and passive materials. For instance, Hamel et al. demonstrated an ML-EA approach to design voxelized composite structures with targeted deformations44, later extended to include voids as functional design elements45. Wu et al. further employed EA-guided design to achieve complex magnetization patterns for soft robots exhibiting biomimetic gaits46, while Ma et al. used deep residual networks to accelerate inverse design under magnetic actuation47. Several studies adopted neural network architectures such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and artificial neural networks (ANNs) for forward prediction and inverse shape matching, particularly in active beams and soft actuators48,49. Sun et al. proposed a hybrid ML and computer vision pipeline for user-defined shape input and fast voxelized material mapping48, later advancing to a real-time subdomain optimization framework with high accuracy and adaptability50. Recent work by Wang et al. combines deep learning and evolutionary algorithms to design 4D printed structures. They developed a sequence-enhanced parallel convolutional neural network (SEP-CNN) to predict the deformation of solvent-responsive hydrogels, integrated with a progressive evolutionary algorithm (PEA) for efficient design51. Other ML strategies include ensemble regressors like random forest or gradient boosting for curvature prediction52, hydrogel behavior modeling for drug delivery53, and polycube-based regression for accelerated shape generation54.

Despite significant progress in inverse design approaches for 4D printed structures, most existing methods are narrowly tailored to specific tasks and often rely on large, application-specific datasets. Furthermore, many approaches assume unconstrained deformation scenarios, limiting their applicability to real-world designs with boundary conditions. To overcome these limitations, we introduce an inverse design framework based on finite element modeling. Our method explicitly incorporates user-defined boundary conditions and nonlinear, time-dependent material behavior, enabling accurate simulation and optimization of shape evolution under external stimuli. Since our method is based on the finite element model, it naturally allows for user-defined target shapes. By computing full-field displacements, the framework supports flexible shape specifications, including bending angles, chord length, and endpoint displacement, and so on. We demonstrate the accuracy and adaptability of our framework through two representative applications: design of a typical 4D printed bilayer actuator and an electrically actuated hydrogel soft gripper. Our main contributions are three folds:

-

We propose an inverse design framework for 4D printed structures, using finite element modeling integrating geometrical nonlinearity and time-dependent behavior.

-

The framework allows users to set custom desired shape and boundary conditions.

-

We demonstrate the applicability of the framework through two representative examples, showing its effectiveness across different external stimuli.

Methods

Constitutive law

To simulate the deformation behavior of 4D printed structures under different stimuli, it is necessary to define appropriate constitutive laws for the materials involved. In this section, we introduce the material models adopted in our framework, which serve as the basis for accurate deformation prediction and inverse design.

In our previous work55, we proposed a model called SFEM-4DP (strain-based finite element model for 4D printing), which composed of the viscoelastic model56 and shrinking/swelling model. The constitutive law of viscoelasticity is formulated as

with

where \(\varvec{\sigma }\) represents total stress, \(E\) represents Young’s modulus, \(c\) represents viscosity coefficient, and \(\varvec{\varepsilon }^{\text {VE}}\) represents the strain generated in the viscoelastic model, \(\nu\) denotes Poisson’s ratio. The symbols \(\textbf{1}_{3\times 3}\) and \(\textbf{0}_{3\times 3}\) represent \(3\times 3\) matrices whose elements are all 1 and 0, respectively. And \(\textbf{I}_{3\times 3}\) signifies the \(3\times 3\) identity matrix.

The total strain of SFEM-4DP can be then expressed as:

with

where \(\varepsilon _x^{\text {4DP}}(t)\), \(\varepsilon _y^{\text {4DP}}(t)\) and \(\varepsilon _z^{\text {4DP}}(t)\) represents the normal strain in the x, y and z axes caused by external stimuli, respectively55. Note that these strain components are functions of time t, introducing the temporal domain into the model. This means they characterize the time-dependent deformation of the smart material in response to external stimuli.

To simulate large deformation and deformation involving rotation, nonlinear Green strain tensor was used in this work57. Then we can obtain the terms in Eq. (6) as follows:

where \(u_{x}^{msr}(t), v_{y}^{msr}(t), w_{z}^{msr}(t)\) are the strains with respect to time, which can be measured by physical calibration experiments.

Finite element modeling

To capture the deformation of 4D printed structures, we implement a finite element modeling that explicitly incorporates boundary conditions. Introducing the velocity vector \(\textbf{v}_N = \dot{\textbf{u}}_N\) and applying Lagrangian mechanics, the following equation can be derived:

with

where \(\textbf{M}\) denotes the mass matrix of 4D printed structure, \(\textbf{A}\) represents the constraint matrix according to applied boundary condition, \(\textbf{0}\) is square matrices whose elements are all 0 and its dimension depends on \(\textbf{A}\), and \(\varvec{\lambda }\) is a collective vector of Lagrange multipliers for each constraint. The vector \(\textbf{b}(t)\) specifies the position of constrained points at time \(t\). \(\textbf{f}_N\) represent the node force vector, whose derivation can be seen in our previous work. The constant \(\alpha\) is set to 2000 in our simulation57. After solving Eq. (10) by using ode23() in MATLAB, we can obtain the full-field displacement \(\textbf{u}_N\).

Schematic illustration of the inverse design framework. The process begins with the specification of initial design parameters of the given object. Then the object is discretized into a finite element mesh using meshObject(). Material properties including measured strain, Young’s modulus, viscosity coefficient, density, color, and Poisson’s ratio, are assigned to specific subregions via setSubregion(). Optional constraints are imposed using applyConstrain(), after which the governing equations are formulated. Deformation is then simulated and visualized using runSimulation(). MATLAB’s built-in fminbnd() algorithm iteratively updates the design parameters after each simulation cycle, and the process repeats until the simulated shape converges to the desired 2D or 3D target deformation.

Inverse design framework

In this section, building upon the finite element model, we develop an inverse design framework that aims to determine optimal design parameters corresponding to a user-defined target deformation.

Figure 1 presents the schematic of the proposed inverse design framework. The process begins with a predefined geometry and an initial guess of the design parameters. The geometry is first discretized into finite elements using the meshObject() function. Next, material properties, including Young’s modulus, viscosity, density, color, and experimentally measured strain, are assigned to subregions using setSubregion() function. Boundary conditions are then imposed through the applyConstraint() function. Once the model setup is complete, a forward simulation is executed via runSimulation() to evaluate the resulting deformation. The computed displacement field is compared to the desired 2D or 3D shape, defined by geometric descriptors such as bending angle, chord length, or endpoint displacement. The functions meshObject(), setSubregion(), applyConstraint(), and runSimulation() have been described in detail in our previous work55.

If the result deviates from the target beyond a user-defined tolerance, the design parameters are updated using MATLAB’s built-in fminbnd() function, which performs bounded scalar optimization based on golden-section search and parabolic interpolation. This closed-loop process proceeds fully automatically, iterating until the simulated deformation closely aligns with the target geometry, at which point the optimal design is finalized and exported.

To clearly illustrate the overall procedure of the inverse design framework, a pseudo-code description is provided in Algorithm 1. This outlines the main computational steps, including initialization, forward simulation, objective evaluation, and iterative updates. Note that the implementation of the calculateDeformation() function may vary depending on the specific design objective. For instance, it may compute bending angle, chord length, or endpoint displacement. However, these target metrics share a common basis: they are all derived from the final deformation displacement, denoted as \(\textbf{u}_N\). And it is worth noting that the present algorithm is only suitable for single-variable optimization.

Numerical simulation cases

To demonstrate the basic validity and feasibility of the proposed inverse design framework, we present two representative numerical cases. This example serves as a preliminary verification of the method’s ability to achieve target shapes with or without defined boundary conditions. Comprehensive application examples and experimental validations are provided in subsequent sections.

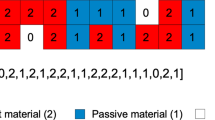

Figure 2(a)-(c) presents the inverse design problem for a typical 4D printed bilayer actuator. The active layer, shown in light blue, is made of hydrogel with a thickness of 3 mm, while the passive layer, shown in orange, is composed of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) with a thickness of 1 mm, illustrated in Fig. 2(a). Deformation occurs due to the swelling of the hydrogel in the active layer. Figure 2(b) shows the target shape 1 without any boundary constraints. In this case, target shape is characterized by the chord length \(l_d\), which is the average distance between the corresponding endpoints on both sides after deformation. In Fig. 2(c), the left bottom part of the structure is fixed. To quantify this deformation, we define the bending angle \(\theta\) as the angle between the horizontal axis and the line connecting the rightmost point of the fixed part to the rightmost point of the hydrogel. The goal of the inverse problem is to determine the optimal length l of the 4D printed structure that results in a specified deformation shape.

Numerical simulation cases of inverse deign. (a) The active layer (light blue) consists of hydrogel, and the passive layer (orange) is made of TPU. The thicknesses of the TPU and hydrogel layers are set to 1 mm and 3 mm, respectively, and an inverse problem needs to be solved to determine the required structural length l that will achieve the target shape. (b) The structure is not fixed and the target shape is defined as length \(l_d\). (c) The left bottom side of the structure is fixed, and the target shape is defined as bending angle \(\theta\). (d) and (e) show the convergence of the design parameter l and the cost function J(l) during the optimization process for two different target configurations. The final optimized values of l are 73.81 mm and 34.87 mm, respectively. Based on these results, (f) and (h) illustrate the initial configurations for each case. The 4D printed structure is meshed using a 31\(\times\) 9 node grid. Red crosses represent applied boundary conditions. Panels (g) and (i) present the final simulation results corresponding to the two design solutions.

Figure 2(d) and (e) demonstrate the convergence behavior of both the design parameter l and the cost function J(l) throughout the optimization procedure. The cost function J(l) throughout the optimization procedure quantifies the discrepancy between the predicted and target deformation metrics as a function of the design parameter l. Its general form is given by:

where \(\mathcal {D}^{\text {pred}}(l)\) denotes the predicted deformation associated with the design parameter l, and \(\mathcal {D}^{\text {target}}\) is the user-specified target deformation.

For deformation characterized by a length parameter \(l_d\), the objective becomes

For deformation measured by a bending angle \(\theta\), the objective becomes

In our simulation cases, the target shape 1 and target shape 2 are set as a chord length of 0 mm and a bending angle of \(60^\circ\), respectively. Here, 0 mm corresponds to a fully curled, doughnut-like configuration of the bilayer structure. It means that \(l_d^{\text {target}} =\) 0 mm and \(\theta ^{\text {target}} = 60^\circ\).

The final optimized values of \(l^*_1\) and \(l^*_2\) are determined to be 73.81 mm and 34.87 mm, respectively. Using these optimized parameters, the initial undeformed structures are simulated and visualized in Fig. 2(f) and (h). Each structure is discretized into a mesh of 31 \(\times\) 9 nodes, with red crosses indicating the applied boundary conditions. The final deformations are further demonstrated in Fig. 2(g) and (i). The deformation videos can be seen in Supplementary Video S1 (Deformation process of the structure in Figs. 2(f)) and S2 (Deformation process of the structure in Fig. 2(h)), respectively.

Design of a 4D printed bilayer actuator

To further validate the feasibility and accuracy of our proposed inverse design framework, we apply it to the design a 4D printed bilayer actuator, as illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown in Fig. 3(a), the Inter-Crosslinking Network (ICN) gel solution is prepared by mixing KarenzMOI-EG, DMAAm, and HPC51,58. Fig. 3(b) illustrates the fabrication of the TPU layer using fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology. Subsequently, as shown in Fig. 3(c), the hydrogel layer is printed directly onto the TPU layer via stereolithography (SLA) to form the bilayer structure. Finally, the printed bilayer is fixed onto the blue fixed part, as depicted in Fig. 3(d). The goal is to achieve specific deformed configurations characterized by a predefined chord length \(l_c\). In this case, the design parameter is the total length of the bilayer structure, denoted as l, which is to be optimized to achieve the desired final shape. The thickness of the TPU in this fixed part is set to 8 mm. To examine the sensitivity and adaptability of the inverse design approach under various material configurations, we consider three bilayer samples with varying hydrogel layer thicknesses h: 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm, while keeping the TPU layer thickness constant at 1 mm for all cases.

Inverse design of a 4D printed bilayer actuator. (a) The ICN gel solution is composed of KarenzMOI-EG, DMAAm, and HPC. Upon 405nm light irradiation, the gel solution undergoes polymerization and transforms into a cured hydrogel. (b) TPU layer is printed by FDM technology. (c) The hydrogel layer is printed onto the TPU layer using SLA technology. (d) Design parameter is the length of the bilayer structure and desired shape is defined as the chord length \(l_c\). (e)-(k) Comparison between simulation and experimental results. Desired chord length 10 mm: (e) hydrogel thickness 1 mm; (f) hydrogel thickness 2 mm; (g) hydrogel thickness 3 mm. Desired chord length 20 mm: (h) hydrogel thickness 1 mm; (i) hydrogel thickness 2 mm; (j) hydrogel thickness 3 mm. (k) Quantitative comparison of the resulting chord lengths between simulations and experiments.

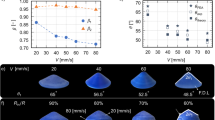

For each configuration, the target chord lengths are set to 10 mm and 20 mm, respectively. Using our inverse design framework, we determine the optimal initial lengths of the bilayer structures required to achieve these target deformations. The resulting optimal design parameters for each case are summarized in Table 1. To validate the design predictions obtained from our inverse design framework, both numerical simulations and experimental tests were conducted. The results are presented in Fig. 3(e)-(k). Specifically, Fig. 3(e)-(j) correspond to the six cases listed in Table 1, each representing a different combination of hydrogel thickness and target chord length. For each case, three samples were fabricated using the 4D printing process to ensure repeatability and assess experimental variability. The deformed shapes observed in the experiments show good agreement with those obtained from simulation, confirming the effectiveness of the design methodology. Furthermore, a quantitative comparison of the resulting chord lengths between simulation and experiment is provided in Fig. 3(k), which illustrates the consistency between predicted and actual performance across all tested conditions.

Design of an electrically actuated hydrogel gripper

To further validate the proposed inverse design framework, we applied it to the development of an electrically actuated hydrogel gripper. It is worth noting that, unlike the hydrogel material used in the previous examples, this gripper employs an electro-active polymer (EAP) hydrogel as the primary active material, enabling controlled deformation under electrical stimulation. The aim of this case study is to demonstrate the adaptability of the framework in designing functional structures beyond bilayer systems and to illustrate its applicability to electrical stimuli.

Characterization and modeling of the electrically responsive EAP hydrogel. (a) Actuation mechanism: under an applied electric field, ion migration drives water transport, leading to nonuniform swelling and bending. (b) Five-layer simulation model of the EAP hydrogel with definition of the gradient swelling factor (GSF) (\(c_g\)) and a simplified assumption of linear dependence on time. (c) Schematic of the experimental setup for extracting \(c_g\), conducted under fixed conditions (20 V, 90 s, 25 \(^{\circ }\)C). (d) Actual experimental setup used for GSF calibration and validation.

The actuation mechanism of the EAP hydrogel relies on ion migration under an electric field. As illustrated in Fig. 4(a), the application of voltage causes charged ions within the hydrogel to move, and water molecules follow due to their affinity with hydrogen ions59. This ion-driven water redistribution leads to nonuniform swelling across the structure, resulting in directional bending. Such behavior enables programmable shape transformation, making EAP hydrogels ideal for soft gripper applications.

(a) Three-step inverse design process for determining the optimal length of an EAP hydrogel structure. Step 1: Experimental characterization of maximum deformation and Young’s modulus under fixed conditions (20 V, 90 s, 25 \(^{\circ }\)C). Step 2: Parameter identification of the GSF (\(c_g = 0.0484\)) based on measured data and sample geometry (25 \(\times\) 5 \(\times\) 10 mm). Step 3: With a target displacement of 16 mm and fixed width and thickness (5 mm and 10 mm), the optimal length of the EAP hydrogel was computed to be 33.3 mm. (b) The developed electrically actuated hydrogel gripper. The width of the finger holder is 32 mm and the length of the hydrogel is 33.3 mm. (c) The convergence of the design parameter EAP hydrogel length l and the cost function J(l) during the optimization process. (d) Deformation process of the designed electrically hydrogel soft gripper. Max displacement is defined as d.

In our work, the hydrogel formulation consists of acrylic acid monomers (15 wt%), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, 400 MW) as the crosslinking agent (0.5 wt%), and \(\alpha\)-ketoglutaric acid as the photoinitiator (0.25 wt%). In the remainder of this work, we refer to this composition simply as the “EAP hydrogel” to distinguish it from previously discussed hydrogel materials.

To simulate the deformation behavior of the EAP hydrogel, we divided the hydrogel structure into five distinct layers, as illustrated in Fig. 4(b), and defined a Gradient Swelling Factor (GSF), denoted as \(c_g\). We propose the following assumption: under identical voltage stimulation, EAP hydrogels synthesized from the same material and in the same environment exhibit the same GSF.

Based on this assumption, the design process is divided into three steps: Step 1: Ensure the repeatability of the experiment by conducting multiple tests under consistent conditions (i.e., same voltage, identical dimensions, identical synthesis method, and same environment). Step 2: According to the experimental results from Step 1, obtain the GSF under these conditions by parameter identification. Step 3: Utilize the GSF obtained in Step 2 to design the gripper fingers accordingly.

To complete Step 1, we tested several groups of samples under consistent conditions. Each sample was subjected to a stimulation voltage of 20 V for 90 s, measured 25 \(\times\) 5 \(\times\) 10 mm, and was tested at room temperature (25 \(^{\circ }\)C). A schematic illustration of the experimental procedure is provided in Fig. 4(c), while the actual experimental setup is shown in Fig. 4(d). The maximum deformation was defined as the displacement d measured at the lower-right corner of the EAP hydrogel, as shown in Fig. 5(d). Based on the test results, the average maximum deformation was found to be 9.549 mm, with a relative deviation of approximately 2.12%. In addition, the Young’s modulus of the samples was measured to be 73.85 kPa, with a relative deviation of about 8.22%.

In Step 2, the average values of maximum deformation (9.549 mm) and Young’s modulus (73.85 kPa) obtained in Step 1 were input into the inverse design framework. This computation resulted in a GSF of \(c_g = 0.0484\).

In Step 3, we assumed that the width and thickness of the EAP hydrogel remained constant at 5 mm and 10 mm, respectively. The goal was to determine the optimal length of the hydrogel that would achieve a target maximum displacement of 16 mm. By incorporating the previously obtained values of GSF (\(c_g\)) and Young’s modulus into our proposed inverse design framework, the optimal design length was calculated to be 33.3 mm. The entire process, including all three steps, is illustrated in Fig. 5(a). The convergence process during optimization is shown is Fig. 5(c).

To validate the correctness of our optimized result, we fabricated a two-finger gripper prototype, as shown in Fig. 5(b). The distance between the two fingers was set to 32 mm, which directly motivated our choice of a target maximum displacement of 16 mm. This displacement ensures that each hydrogel actuator contributes equally, allowing the opposing fingers to fully close and securely grasp an object. We selected maximum displacement as the primary deformation metric because it directly corresponds to the gripper’s functional requirement of complete closure, which is essential for reliable object manipulation. Each finger was fabricated using the EAP hydrogel with dimensions of 33.3 \(\times\) 5 \(\times\) 10 mm, as determined in Step 3. An electric voltage of 20 V was applied at room temperature, and the deformation process was recorded over a 90 s duration.

The final deformation process of the designed electrically hydrogel soft gripper is shown in Fig. 5(d). We tested three grippers, each consisting of two fingers, resulting in a total of six fingers. The maximum displacement of each finger was quantified using ImageJ software. The averaged maximum displacement across all six fingers over three experimental trials was 14.86 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.57 mm. Details are provided in Supplementary Figure S1 (Maximum displacement measurements of six fingers, tested over three independent experimental trials. Displacements were analyzed using ImageJ. The desired max displacement is 16 mm. The actual max displacement is 14.592 mm, 15.104 mm, 14.180 mm, 15.184 mm, 15.738 mm, 14.414 mm) and Supplementary Video S3-S5 (Experimental videos of electrically actuated hydrogel gripper). These results indicate a close match between the actual max displacements and the desired max displacements, which validates the feasibility of the proposed inverse design framework.

Discussion

This study demonstrates an inverse design framework that combines nonlinear material behavior, time-dependent viscoelastic response, and finite element method into a computational tool for 4D printing. Two representative case studies verified the accuracy and feasibility of the framework. Although the present validation focused on hydrogels, the underlying formulation is not confined to this material class. As a theoretical illustration, one could fabricate a simple shape memory polymer (SMP) block and experimentally determine its Young’s modulus E, Poisson’s ratio \(\nu\), and the measured strains \(\varvec{\varepsilon }^{\text {4DP}}\) in three principal directions, under a prescribed thermal stimulus. By substituting these experimentally obtained quantities into the framework, it could predict the evolution of an SMP-based structure under the same thermal loading and could also be employed to design an SMP-based structure for a prescribed target deformation. This example suggests that the framework has the potential to extend beyond hydrogel systems to other classes of active materials that are commonly used in 4D printing.

The proposed framework offers several advantages. It incorporates geometrical nonlinearity and viscoelastic effects, which enables accurate simulation of shape evolution and allows the determination of the initial printed geometry required to achieve a prescribed target deformation. Compared with data-driven or machine learning strategies, the method requires only experimentally measured material parameters and avoids the need for large training datasets. In our previous work51, we also explored data-driven approaches for predicting the behavior of 4D printed hydrogel structures. However, this required extensive time to collect sufficient data and the prediction capability was ultimately limited to two specific materials in two-dimensional cases. Whenever the material system or type of stimulus was changed, a new round of data collection became necessary, which greatly restricted applicability. Motivated by these challenges, we developed the present framework as an alternative. By validating it with different hydrogels of different properties and under distinct stimuli, including both hydro-driven and electrically driven actuation, we demonstrated that the proposed method provides a more suitable design strategy in situations where large datasets are not available. That is to say, in situations where sufficient data are not available, the proposed framework provides a practical and effective design approach. The framework also accommodates user-defined target shapes and boundary conditions, making it adaptable to diverse design objectives. Furthermore, since the formulation is expressed at the strain level, it can be calibrated for different external stimuli by measuring only the strain response, rather than determining a full set of physical parameters.

Several limitations should also be acknowledged. The current implementation employed a bounded scalar optimization scheme that is suitable for problems with a single design variable, such as the gripper length. This was sufficient to demonstrate feasibility but does not scale directly to higher-dimensional design spaces where multiple parameters, such as length, thickness, and material distribution, need to be optimized simultaneously. As also reflected in Fig. 2(g), another limitation is that the current framework does not capture self-contact or contact with external objects, which may become critical in complex deformation scenarios. In addition, the gripper case relied on the simplifying assumption that the Gradient Swelling Factor is constant under identical conditions. While this assumption was validated experimentally for the geometries studied, it may not remain valid for substantially different electric field distributions or structural scales. Furthermore, for both the bilayer actuator and the gripper examples, each finite element simulation run (i.e., one iteration) typically required less than 10 minutes, depending on the mesh size and the specific task. The complete optimization was finished within two hours. All computations were performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) w3-2435 3.10 GHz processor. While the proposed approach avoids the extensive data collection required by data-driven methods, its prediction speed is relatively slower compared with data-driven strategies because the framework relies on finite element method, and the computational cost increases with system size. Therefore, further improvements in computational efficiency will be necessary for more complex applications.

Conclusions and future work

In this paper, an inverse design framework for 4D printed structures was developed and validated. The framework enables programmable shape transformation under external stimuli by reformulating the inverse problem as an optimization task. Through this process, the initial printed geometry can be computed to achieve a desired final configuration. Two case studies, a bilayer actuator and an electrically actuated hydrogel gripper, were presented to evaluate the method. The simulated deformations closely matched experimental results, confirming the accuracy and predictive capability of the framework. The successful application to both hydro-driven and electrically-driven hydrogels highlights the adaptability of the method to different material systems and actuation mechanisms. The results demonstrate the practical value of the framework as a computational design tool for inverse problems in 4D printing. It provides an efficient and reliable pathway for realizing programmable shape-morphing structures.

Future developments will focus on extending the framework in several directions. First, the simplifying assumption of a constant Gradient Swelling Factor, while effective for the present study, requires further evaluation across a wider range of geometries and electric field distributions. Second, the current optimization scheme, which is limited to single-variable problems, will be expanded to handle multi-variable optimization. Gradient-based solvers can be employed for smooth design landscapes, while heuristic or population-based algorithms such as genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization may provide robustness in more complex or non-convex design spaces. These methods would enable simultaneous optimization of multiple design variables, including length, thickness, and material distribution. Third, our current experimental platform is restricted to 4D-printed structures with hydrogels as the active material, and a comprehensive validation of other smart materials remains beyond the scope of this study. Future efforts will therefore be directed toward extending experimental validation to shape memory polymers, liquid crystal elastomers, magneto-active composites, and other emerging 4D printing methods. We also plan to extend the framework to incorporate contact mechanics, so that self-contact and interactions with external bodies can be consistently captured. Finally, improving computational efficiency, incorporating more rigorous mesh quality control, and broadening the scope of material validation will further enhance the applicability of the framework to complex and large-scale 4D printing problems.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15861988, reference number 15861988.

References

Tibbits, S. The emergence of “4d printing”. In TED conference (2013).

Tibbits, S. 4d printing: multi-material shape change. Archit. design 84, 116–121 (2014).

Khoo, Z. X. et al. 3d printing of smart materials: A review on recent progresses in 4d printing. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 10, 103–122 (2015).

Sydney Gladman, A., Matsumoto, E. A., Nuzzo, R. G., Mahadevan, L. & Lewis, J. A. Biomimetic 4d printing. Nat. materials 15, 413–418 (2016).

Momeni, F. et al. A review of 4d printing. Mater. & design 122, 42–79 (2017).

Yarali, E. et al. 4d printing for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402301 (2024).

Wan, X. et al. Recent advances in 4d printing of advanced materials and structures for functional applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312263 (2024).

Bodaghi, M. et al. 4d printing roadmap. Smart materials and structures 33, 113501 (2024).

Khalid, M. Y., Arif, Z. U., Noroozi, R., Zolfagharian, A. & Bodaghi, M. 4d printing of shape memory polymer composites: A review on fabrication techniques, applications, and future perspectives. J. Manuf. Process. 81, 759–797 (2022).

Arif, Z. U., Khalid, M. Y., Zolfagharian, A. & Bodaghi, M. 4d bioprinting of smart polymers for biomedical applications: Recent progress, challenges, and future perspectives. React. Funct. Polym. 179, 105374 (2022).

Ge, Q. et al. Multimaterial 4d printing with tailorable shape memory polymers. Sci. reports 6, 31110 (2016).

Champeau, M. et al. 4d printing of hydrogels: a review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1910606 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. 4d printed hydrogels: fabrication, materials, and applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000034 (2020).

Li, H., Bartolo, P. J. D. S. & Zhou, K. Direct 4d printing of hydrogels driven by structural topology. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 20, e2462962 (2025).

Chen, M. et al. Recent advances in 4d printing of liquid crystal elastomers. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209566 (2023).

Guan, Z., Wang, L. & Bae, J. Advances in 4d printing of liquid crystalline elastomers: materials, techniques, and applications. Mater. Horizons 9, 1825–1849 (2022).

Jiang, H., Chung, C., Dunn, M. L. & Yu, K. 4d printing of liquid crystal elastomer composites with continuous fiber reinforcement. Nat. Commun. 15, 8491 (2024).

Chen, M., Hou, Y., An, R., Qi, H. J. & Zhou, K. 4d printing of reprogrammable liquid crystal elastomers with synergistic photochromism and photoactuation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2303969 (2024).

Momeni, F. & Ni, J. Laws of 4d printing. Engineering 6, 1035–1055 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Botanical-inspired 4d printing of hydrogel at the microscale. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907377 (2020).

Wan, X. et al. Recent advances in 4d printing of advanced materials and structures for functional applications. Adv. Mater. 2312263 (2024).

Peng, X. et al. 4d printing of freestanding liquid crystal elastomers via hybrid additive manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204890 (2022).

Imani, K. B. C., Kim, D., Kim, D. & Yoon, J. Temperature-controllable hydrogels in double-walled microtube structure prepared by using a triple channel microfluidic system. Langmuir 34, 11553–11558 (2018).

Strong, V., Holderbaum, W. & Hayashi, Y. Electro-active polymer hydrogels exhibit emergent memory when embodied in a simulated game environment. Cell Reports Phys. Sci. 5 (2024).

Khalid, M. Y. et al. 3d printing of magneto-active smart materials for advanced actuators and soft robotics applications. Eur. Polym. J. 205, 112718 (2024).

Lucarini, S., Hossain, M. & Garcia-Gonzalez, D. Recent advances in hard-magnetic soft composites: Synthesis, characterisation, computational modelling, and applications. Compos. Struct. 279, 114800 (2022).

Bastola, A. K. & Hossain, M. The shape-morphing performance of magnetoactive soft materials. Mater. & Des. 211, 110172 (2021).

Yarali, E. et al. Magneto-/electro-responsive polymers toward manufacturing, characterization, and biomedical/soft robotic applications. Appl. Mater. Today 26, 101306 (2022).

Hou, Y., Zhang, H. & Zhou, K. Ultraflexible sensor development via 4d printing: Enhanced sensitivity to strain, temperature, and magnetic fields. Adv. Sci. 12, 2411584 (2025).

Khalid, M. Y. et al. 4d printing: Technological developments in robotics applications. Sensors Actuators A: Phys. 343, 113670 (2022).

Xin, C. et al. Environmentally adaptive shape-morphing microrobots for localized cancer cell treatment. ACS nano 15, 18048–18059 (2021).

Qi, Q. et al. The rise of transient robotics. Device 2 (2024).

Hann, S. Y., Cui, H., Nowicki, M. & Zhang, L. G. 4d printing soft robotics for biomedical applications. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101567 (2020).

Darkes-Burkey, C. & Shepherd, R. F. Volumetric 3d printing of endoskeletal soft robots. Adv. Mater. 2402217 (2024).

Zolfagharian, A., Kaynak, A. & Kouzani, A. Closed-loop 4d-printed soft robots. Mater. & Des. 188, 108411 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. 4d printing of magneto-and thermo-responsive, adaptive and multimodal soft robots. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 20, e2457025 (2025).

Zolfagharian, A. et al. 3d/4d-printed bending-type soft pneumatic actuators: Fabrication, modelling, and control. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 15, 373–402 (2020).

Zolfagharian, A., Denk, M., Bodaghi, M., Kouzani, A. Z. & Kaynak, A. Topology-optimized 4d printing of a soft actuator. Acta Mech. Solida Sinica 33, 418–430 (2020).

Chen, X., Yang, M., Jia, K. & Yuan, C. 4d printed stiffness-tunable actuator for load-bearing soft machines. Adv. Mater. Technol. 9, 2400074 (2024).

Kwok, T.-H. & Chen, Y. Gdfe: Geometry-driven finite element for four-dimensional printing. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 139, 111006 (2017).

Wang, G. et al. 4dmesh: 4d printing morphing non-developable mesh surfaces. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 623–635 (2018).

An, B. et al. Thermorph: Democratizing 4d printing of self-folding materials and interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–12 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. A 4d-printing inverse design strategy for micromachines with customized shape-morphing. Small 19, 2302656 (2023).

Hamel, C. M. et al. Machine-learning based design of active composite structures for 4d printing. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 065005 (2019).

Athinarayanarao, D. et al. Computational design for 4d printing of topology optimized multi-material active composites. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 1 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Evolutionary algorithm-guided voxel-encoding printing of functional hard-magnetic soft active materials. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 2000060 (2020).

Ma, C., Chang, Y., Wu, S. & Zhao, R. R. Deep learning-accelerated designs of tunable magneto-mechanical metamaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. & Interfaces 14, 33892–33902 (2022).

Sun, X. et al. Machine learning-evolutionary algorithm enabled design for 4d-printed active composite structures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109805 (2022).

Zolfagharian, A. et al. 4d printing soft robots guided by machine learning and finite element models. Sensors and Actuators A: Phys. 328, 112774 (2021).

Sun, X. et al. Machine learning and sequential subdomain optimization for ultrafast inverse design of 4d-printed active composite structures. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 186, 105561 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Fast reverse design of 4d-printed voxelized composite structures using deep learning and evolutionary algorithm. Adv. Sci. 2407825 (2024).

Su, J.-W. et al. A machine learning workflow for 4d printing: understand and predict morphing behaviors of printed active structures. Smart Mater. Struct. 30, 015028 (2020).

Suryavanshi, P., Wang, J., Duggal, I., Maniruzzaman, M. & Banerjee, S. Four-dimensional printed construct from temperature-responsive self-folding feedstock for pharmaceutical applications with machine learning modeling. Pharmaceutics 15, 1266 (2023).

Yu, Y., Qian, K., Yang, H., Yao, L. & Zhang, Y. J. Hybrid iga-fea of fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites for forward design of ai-enabled 4d printing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 302, 117497 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Sfem-4dp: A strain-based finite element model for 4d printing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 110497 (2025).

Wang, Z. & Hirai, S. Modeling and parameter estimation of rheological objects for simultaneous reproduction of force and deformation. In 1st International Conference on Applied Bionics and Biomechanics (2010).

Wang, Z. & Hirai, S. Green strain based fe modeling of rheological objects for handling large deformation and rotation. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 4762–4767 (IEEE, 2011).

Kameoka, M. et al. 4d printing of hydrogels controlled by hinge structure and spatially gradient swelling for soft robots. Machines 11, 103 (2023).

Strong, V. Soft computation using electro-active polymer hydrogels. Ph.D. thesis, University of Reading (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Chinese Government Scholarship under Grant CSC202106220079 and the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization under Grant JPNP14004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. proposed and implemented the method, designed the experiments, and prepared the manuscript. K.B.C.I. developed and fabricated the hydrogel used for the electrically actuated components. M.W. provided guidance on figure preparation. S.M. supervised the study and contributed to review and editing. H.F. provided the fabrication method for the ICN gel and the hydrogel printer. S.H. contributes to code development and method implementation. Z.W. proposed the method, supervised the study, and contributed to review and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Betha Cahaya Imani, K., Wang, M. et al. Inverse design framework for 4D printed structures using the finite element method. Sci Rep 15, 42481 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26598-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26598-6