Abstract

The misuse and overuse of pesticides can lead to crop contamination and accumulating pesticide residues in the food chain, raising serious public health concerns. This study assessed penconazole residue levels in grape samples from Gonabad’s vineyards and evaluated the associated human health risks. In 2022, grape samples were collected from 13 vineyards and analyzed. Penconazole levels in unwashed, water-washed, and disinfected grape samples were 0.256 (0.154–0.391) mg/kg, 0.195 (0.094–0.335) mg/kg, and 0.051 (0.027–0.089) mg/kg, respectively. Although penconazole was detected in all samples, its concentration remained below the EU’s Maximum Residue Level (MRL) of 0.4 mg/kg. Washing and disinfection reduced penconazole residues by 23.8% and 80%, respectively, with the highest residues observed in unwashed grapes. The hazard quotient (HQ) values for unwashed, washed, and disinfected samples were below 1, indicating negligible non-cancer health risks for teenagers and adults consuming these grapes. These findings suggest that grape consumption poses minimal health risks related to penconazole residues. This study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of washing and disinfection in reducing pesticide residues and highlights the importance of monitoring pesticide levels to ensure food safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fruits provide essential nutrients and vitamins for human health. However, plants may adsorb contaminants from water, soil, and air and accumulate them in their seeds and fruits, raising concerns about their safety and potential health risks. Different human activities, including industrial discharges, inappropriate waste disposal, and extensive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, have resulted in the pollution of the environment and eventually crops1,2,3. Pesticides cover different compounds, including insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, rodents, molluscicides, nematicides, and plant growth regulators4. These substances are universally used in agriculture to kill, repel, or control pests, diseases, and weeds, but their levels can persist in many farm-produced crops5,6. Different types of pesticides are used in various regions and nations to control pests, insects, and weeds on different types of agricultural products. Due to the expansion of global trade, more crops that are treated by pesticides are being imported into different nations7. Many factors affect the levels of pesticides in crops which are including the type of pesticide used, application methods, frequency of application, pre-harvest intervals, irrigation frequency, and climate and geology of the farming area5,8. Penconazole is a common fungicide used by many farmers around the world to control fungal pathogens on fruits and vegetables9,10,11. This systemic triazole fungicide is mostly applied by grape growers to protect them from fungal diseases such as powdery mildew and downy mildew12,13. The extensive application of this substance has raised particular attention due to its potential toxicity and persistence in the environment14. The use of fungicides in grapes is a conventional and ancient agricultural practice, which provides many advantages but, unfortunately, some disadvantages as well15,16,17. Penconazole is a widely used fungicide in Iran, and it is currently one of the most abundantly used pesticides in Iranian vineyards. However, improper use, overuse, or inadequate adherence to withdrawal periods may eventually result in the presence of penconazole residues in harvested grapes, which can subsequently find their way into the food supply chain18,19,20. The consumption of grapes and their processed products contaminated with residual penconazole can cause serious health effects, ranging from short-term poisoning to chronic cumulative effects21,22,23. Scientists have reported that penconazole can interfere with hormone systems and potentially affect the endocrine system. It may also cause reproductive, developmental, and neurotoxic problems in animals14,24,25,26,27,28. The World Health Organization in 199229 and the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA)30 have proposed an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 0.03 mg/kg body weight/day. Although there are limited human studies in the literature, these reports raise concerns about the potential risks linked to the consumption of grapes containing penconazole. Different grape types may show variations in residual pesticide concentrations due to variations in cultivation practices and susceptibility to pests. Considering these variations can help consumers in making choices that align with their preferences and concerns linked to pesticide exposure. The most common grape varieties in Gonabad are “Hosseini/Rishbaba (Vitis vinifera L.,c.v. Hosseini)”, “Asgari (Vitis vinifera L.,c.v. Asgari)”, and “Siah (Vitis vinifera L.,c.v. Siah)”. To combat grape powdery mildew disease, penconazole is applied via spraying three times throughout the growing season. The first application takes place towards the end of March, followed by two more sprays that depend on the amount of rainfall and temperature. Typically, these sprays are carried out in late April and May (about two months before the first harvest). The Hosseini variety was selected for analysis due to its regular consumption in a fresh state and its relatively brief interval between spraying and harvesting. Due to the health effects of pesticide residues in grapes, it is necessary to reduce pesticide use in agriculture. Unfortunately, the preventive methods of pesticide application have not been well-received by farmers and gardeners in Gonabad, we noticed a notable concern regarding the application of penconazole in the vineyards may not always be executed with the proper training and attention to detail. Our observations indicated that some gardeners might rely on external assistance for the application of penconazole, or they may acquire and utilize products solely based on recommendations from sellers, often lacking a comprehensive understanding of the product and its necessary application protocols. Since penconazole was the only pesticide reported to be used during the ripening period in the studied vineyards, monitoring its residue levels in grapes consumed by the local population is essential to ensure food safety and protect public health. This work aims: (1) to determine the residual concentrations of penconazole in the grapes that are consumed by the individuals and compare them with the existing limits, (2) to evaluate the effectiveness of two various washing methods in the reduction of penconazole residues, (3) to estimate the potential health risks associated with the consumption of grapes containing penconazole residues by using the Monte Carlo simulation and integrating the residue data, consumption patterns, maximum residual limits (MRLs), and toxicological reference dose. The finding of the present study provides useful information regarding the current state of contamination of grapes with penconazole. The results obtained in this study can also be used to develop strategies for regular management and monitoring of grapes for the safety of people consuming these agricultural products.

Materials and methods

Study area

Gonabad is situated at coordinates 34.3530° N, 58.6838° E, and lies to the south of Khorasan Razavi within the east of Iran. Encompassing an expanse of 5788 km2, its altitude rests at 1105 m above sea level. During the 2016 census, its population stood at 40,773. In terms of climate, Gonabad is located in a semi-arid, arid zone, which borders a desert. The city typically experiences an annual precipitation of around 150 mm, while the average yearly temperature ranges between 16.4 and 17.3 °C. This city has been experiencing a severe drought crisis for the past 15 years.

Sampling technique

Grape samples were collected through a purposive sampling technique. Thirteen vineyards within the study area were randomly selected according to predefined criteria, including the cultivation of the Hosseini grape variety and the application of penconazole during the ripening period. From each vineyard, 3 trees were randomly selected, and from each tree, 2 bunches were picked, resulting in a total of 78 bunches. Weigh of grapes sampled in each vineyard was approximately 3.5 kg. Sampling was conducted during the first week of August. Immediately after sampling, the collected samples were carefully placed in clean polythene bags and then in cool box and transported to the laboratory. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the grapes were stored at freezing temperature for subsequent analysis within the same week. Locations of sampled vineyards are shown in the Fig. 1.

Location of sampled vineyards in Gonabad (created using QGIS version 3.10.0-A Coruña https://qgis.org/download/).

Washing of grape samples

To assess the influence of washing on pesticide residue concentration, the subsequent procedure was implemented: given that a significant portion of the community employs tap water as the main method for washing grapes, while only a minority resorts to disinfectant solutions, the grape samples from each vineyard were categorized into two distinct groups in the laboratory. The first set underwent a washing process using tap water (W), while the subsequent set was subjected to cleansing using a commercial disinfectant solution (D). The most popular commercial disinfectant was prepared by consulting with major pharmacies and stores within the city to prepare the disinfectant solution. The washing procedure followed the instructions for this particular product (the grapes were immersed in 1.25 mL of disinfectant per 1 L of water for 10 min). The chemical compound of the disinfectant encompassed deionized water, benzalkonium chloride, and cocoamidopropyl betaine.

Chemicals and reagents

Penconazole residues in grape samples were extracted using a modified QuEChERS method based on previous studies (El-Sheikh et al., 2022; Heshmati et al., 2020). All reagents used were of analytical grade. Penconazole standard (purity > 99%) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). Acetonitrile (C2H3N), sodium chloride (NaCl), anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO), Triphenylmethane (C19H16), Formic acid (HCOOH, 5%), and primary secondary amine (PSA) were purchased from Merck (Germany).

Extraction procedure

For the extraction of the penconazole in the grape samples QuEChERS method prescribed in previous studies was employed31,32. In this method, each grape sample (approximately 1 kg) was homogenized using a laboratory blender for 2 min until a uniform slurry was obtained. From this homogenate, 10 g was taken for analysis. Then, 40 µL of internal standard (triphenylmethane, C19H16) was added to the 10 g sample and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. The volume of extract for clean-up was 0.5 mL.

Subsequently, 12 mL of acetonitrile, 1 g NaCl, and 0.5 g MgSO₄ were added. The mixture was vortexed at 4000 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant (organic phase) was transferred to a clean tube containing 1 g MgSO₄ and 0.5 g PSA, then vortexed again under the same conditions. Four milliliters of the clarified extract were transferred to a Falcon tube, and 40 µg/L of formic acid (5%) was added for stabilization before analysis.

Instrumental analysis and validation

For analysis of penconazole residue, 2 µL of the extract was injected into gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS; Agilent 7890 A GC coupled with a 7000 Triple Quad MS, Agilent Technologies, USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). The injector temperature was set at 250 °C, and the oven temperature program was: initial 70 °C (held for 2 min), increased to 180 °C at 25 °C/min, then to 280 °C at 10 °C/min (held for 5 min). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The MS/MS detector operated in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode with electron impact ionization (EI, 70 eV). The duration of sample injection, separation on GC column and detection was in the range from 25 to 30 min. The number of analytical replicates for the penconazole detection by GC was 3 replicates per grape sample.

The method was validated according to standard guidelines for analytical performance, demonstrating excellent linearity with a coefficient of determination (R²) greater than 0.998 over the concentration range of 0.005–2 mg/kg. The limit of detection (LOD) was determined to be 0.00352 mg/kg, while the limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.01 mg/kg. Recovery rates for fortified grape samples at 0.05 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg levels ranged from 89.7% to 94.3%, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) below 10%. These validation parameters underscore the method’s robustness and suitability for accurate quantification of penconazole residues in grape matrices.

Matrix-matched calibration curves were employed to account for potential matrix effects, prepared by spiking blank grape extracts with penconazole at seven concentration levels (0.005–2.0 mg kg⁻¹) in conjunction with the internal standard (triphenylmethane at 1 mg mL⁻¹ in acetonitrile). For mass spectrometric detection, the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions included a precursor ion at m/z 248.0, yielding product ions at m/z 157.0 (quantifier ion, collision energy [CE]: 22 eV) and m/z 192.0 (qualifier ion, CE: 12 eV), with dwell times of 50 ms per transition. The internal standard transition was m/z 243.0 → 182.0 (CE: 15 eV). The retention time for penconazole was approximately 15.4 min under these conditions, enabling reliable reproduction of the method on equivalent GC-MS/MS systems (Agilent 7890 A GC coupled with a 7000 Triple Quad MS). Key chromatograms for the lowest spiked concentration (LOQ level, 0.01 mg/kg) are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S2).

Health risk assessment

Health risk was estimated by using the method proposed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). In the current study, non-cancer health risk associated with grapes containing penconazole was estimated using Eqs. 1 and 2, as follows:

Where EDI is expressed as the estimated daily intake of penconazole through grape consumption (mg/kg/d), \(\:{C}_{\:Penconazole}\) shows the concentration of penconazole in each sample (mg/kg), \(\:{W}_{grapes}\) is the average daily weight of grapes consumption in the study area (0.17 kg/day for teenagers, and 0.22 kg/day for adults), F represents the exposure frequency to pencozazole (90 days per year), D belongs to the exposure duration (17 years for teenagers and 55 years for adults), BW is the average body weight of investigated people (55 kg teenagers and 70 for adults), AT is the time duration of peoples exposure expressed in days calculated by F×D, and RfD is the oral reference dose of penconazole (0.8 mg/kg/day). HQs ≤ 1 indicate that adverse effects may not occur and thus can be considered to have a negligible health risk. If HQ is above 1 (HQs > 1), it shows an unacceptable health risk to consumers33.

Based on the detected residue levels and the characteristics of long-term dietary exposure, the chronic dietary risk was assessed in this study.

Monte Carlo simulation

Health risk assessments are the probability of adverse effects in the human body that take into account risk sources, exposure routes, and risk receptors. However, uncertainty is inherent in risk assessment, and uncertainty is explained as a lack of knowledge of the actual value of variables. Due to uncertainties, specific risk assessments must be considered with different approaches. The Monte Carlo simulation proposed by USEPA is a probability risk assessment method to characterize uncertainty by assessing health risks based on the range and statistical distribution of exposure variables34. The probability risk assessment method used in the current study takes into account the variability of the parameters and analyses the best-fit distribution with all possible values for exposure parameters using a Monte Carlo simulation with 100,000 iterations by MATLAB. The input variables change throughout the iteration, a new value is assigned to find the risk of each subpopulation, incorporating random elements during analysis. The percentile values obtained by the probabilistic approach, which show from a minimum to an extreme range of scenarios, are the 5th percentile representing the minimum or minimum risk scenario, and the 95th percentile representing the worst or extreme risk scenario35. The Q-Q plot shows the normal distribution for the residue concentration (Figure S1) and is taken into account for the normal distribution of other variables.

Ethics approval

This study did not involve human or animal participants; however, ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Approval No. IR.GMU.REC.1400.072 see Figure S3 for Approval statement). The research was conducted in accordance with international ethical standards for plant studies. The investigated species, Vitis vinifera L., is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Therefore, the study fully complies with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). All grape samples were obtained from fruits that had already been harvested by local farmers for commercial sale. No plants were damaged, uprooted, or destroyed during the research. Written permission for sampling was obtained from the orchard owner, and verbal consent was confirmed in the presence of witnesses. Sampling was carried out exclusively during the farmers’ regular harvest period and aligned with standard agricultural practices.

Consent to participate

To uphold informed consent principles, study procedures were thoroughly explained to grape orchard owners, and verbal consent was secured in the presence of witnesses (see SM, p4).

Results and discussion

Occurrence of penconazole residues in grapes

Table 1 summarizes the penconazole residues (the average of three independent measurements) in the analyzed grape samples considered in this study in different washing scenarios. Penconazole residues were detected in all analyzed grape samples. The levels of penconazole in unwashed grape samples, in water-washed samples, and disinfected samples were 0.256 (0.154–0.391) mg/kg, 0.195 (0.094–0.335) mg/kg, and 0.051 (0.027–0.089) mg/kg. Existing EU MRL (mg/kg) penconazole in Table grapes is 0.2 mg/kg. Hence, the European Union proposed an MRL for penconazole in grapes as 0.4 mg/kg36. In this study, the results are compared with 0.4 mg/kg limit. In all the grape samples, the detected penconazole levels were below the MRL established by European legislation. For Iran, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection established 0.4 mg/kg MRL for penconazole in grapes37. All the samples had penconazole levels within Iranian MRL. Scientists have investigated the dissipation behavior of penconazole in some agricultural products such as tomatoes, peaches, plums, apricots, mango, and grapes38,39,40,41. Therefore, penconazole residues in crops and the environment should be monitored regularly. In a previous study, pesticide residues in grapes were investigated. In total, 29 pesticide residues were detected in grapes. Penconazole was found in 50% of the studied samples with concentrations ranging from 0.002 to 0.044 mg/kg42. Mean levels of penconazole residues found in Italian and South African table grapes were 0.029 and 0.009 mg/kg, respectively43. In another work, levels of penconazole pesticides in almost all the grape leaves and fruit samples were within the MRLs44. In a recent study, pesticide residues in 92% of samples of date fruits in Iran were following the national MRLs45. Concentrations of 172 pesticide residues in table grapes in Turkey were studied. One or more pesticide residues were found in 59.6% of the samples of grapes. 20.4% of the collected grape samples exceeded the EU MRLs46. Researchers in a systematic review and meta-analyses reported 0.67–1.43 mg/kg fungicides in grapes6. Fungicide residues were found in 52.0% of the analyzed samples (currants, apples, and cherries) of Polish fruits. Based on the study, 50.20% of the samples had fungicide levels below MRLs and 1.7% above MRLs47. Fifty-one pesticide residues were found in the strawberry samples in Shanghai, China. Among the studied samples, levels of pesticide residues in 2.39% of the samples exceeded MRLs of the EU. The mean level of penconazole concentration in the strawberries was 27 µg/kg, with no sample above the MRLs48. Penconazole is hepatotoxic, damages cardiac oxidative, DNA, causes structural and functional testicular impairment in rats, and affects the growth and protein amount of Scenedesmus acutus41. It is also a possible thyroid carcinogen14.

In another work in Shanghai, a total of forty-four, ten, ten, eighteen, and seven types of pesticides were found in strawberries, watermelons, melons, peaches, and grapes, respectively. The pesticide concentrations in 95.0% of the selected samples were within MRLs recommended by China, and in 66.2% of the studies, samples were less than the EU MRLs49. In the Kampala Metropolitan Area in Uganda, 21 classes of pesticides were found in the fruit and vegetables analyzed50. In a study in Turkey, residues of 64 different pesticides were found in 3044 fruit and vegetable samples, in which 11.6% of samples were higher than the approved MRL level by the Turkish authorities51. Among the local fruits and vegetables in Incheon, Korea, 92.1% had no detectable residue levels, while 7.9% had residues, and 1.0% had residues higher than the Korean MRLs52. In a study in the southeastern region of Poland, pesticide residues were detected in 36.6% of the investigated fruits and vegetables in Poland. In 1.8%, residues were higher than MRLs53. In a research in Algeria, pesticide residues in fresh fruits and vegetables from domestic production and import were investigated, in 42.5% of the analyzed samples no residues were detected, and 12.5% of samples contained pesticide residues exceeding the MRLs54. Researchers studied pesticide residues among locally produced fruits and vegetables in Monze district, Zambia. Results showed detectable levels in 63.3% of the thirty analyzed samples, out of which 3 samples contained levels above the Codex Alimentarius maximum residual limit (0.1 mg/kg). However, all the fruits and vegetables had residues less than the Zambia Food and Drugs standard (0.5 ppm)55. In a study regarding pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables in Saudi Arabia, most of the pesticide residues were lower than the national Codex MRLs. The results also showed that 7.44% of the investigated samples contained residues above MRLs56.

Efficiency of washing and disinfection in the removal of penconazole residues from grapes

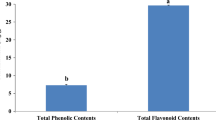

Several methods, including washing, immersing, peeling, husking, cooking, and sterilization, boiling, and frying, can reduce the concentrations of pesticides in fruits and vegetables31,57,58,59. Washing is the second suggested method for reducing pesticide residues in food57. In this study, the capability of washing with water and disinfection in the removal of penconazole residues from grape samples was investigated. Mean levels of penconazole residue are shown in the Figure. 2. As seen in the figure, the order of penconazole residue reductions, considering mean levels, is unwashed > washed by water > disinfected samples. Washing with tap water significantly reduced penconazole residues (R²=0.947), indicating that simple water rinsing is partially effective. The fungicide residues in washed samples were reduced by a mean of 23.8%, which indicates that the process of washing the grapes with water is partially efficient in removing the residue in the fruit. This is in agreement with previous studies60,61,62. Previous studies showed that water washing reduced pesticide residues in the ranges of 16–44%62, 31–70%63, 0–74%64, 47–53%65, 22%66, 30%67 and 27–41%68 in tomato samples. The efficiency of the washing process in the reduction of pesticide residues depends on chemical properties, mode of use, pesticide water solubility of the relevant pesticides, and harvest times69. Generally, it is reported that the pesticides remain in the outer wax-like layers of fruits and vegetables and then enter inside, making the washing process and elimination of the pesticides considerably impractical70,71. The washing process can decrease levels of pesticide residues in the fruits. In another research, scientists reported up to 48% removal of lufenuron when tomato samples were washed with a detergent67. The results of the two recent studies are less than the result of the present study, mainly due to the use of benzoalkanium in addition to a detergent, and also due to different study conditions.

In previous research, the reduction efficiencies of pesticides in grape samples using tap water and NaHCO₃ were studied. The removal of pesticides, including penconazole, hexaconazole, diazinon, ethion, and phosalone, after fifteen minutes of washing with tap water was 20.26%, 18.50%, 37.52%, 15.15%, and 16.59%, respectively31which is similar to the mean 23.8% reduction using water washing in the present study. In the case of NaHCO₃, the reduction of penconazole, hexaconazole, diazinon, ethion, and phosalone was found to be 94.47%, 93.65%, 95.39%, 71.56 and 63.13%, respectively31. In the present work, the use of disinfectant washing (benzalkonium chloride and cocoamidopropyl betaine) resulted in 80% removal of penconazole from grape samples. Washing with disinfectant significantly reduced penconazole residues (R²=0.931). The increase in the removal of penconazole when a disinfectant is used in the current study is likely due to the partial elimination of the wax layer on the grapes where the fungicide is bound. Removal of the wax layer was also reported to be effective in pesticide removal, where tap water, sodium bicarbonate, and acetic acid were used on fruits and vegetables31. Studies have shown a range of 22–92% removal of pesticides when tomatoes were washed with sodium bicarbonate63,64,68,72.

Although the penconazole residue levels found in the present work are within the MRLs and close to those found in literature, the usage of pesticides in vineyards must not be increased. Using other non-chemical control measures for powdery mildew disease could therefore somewhat compensate for this problem.

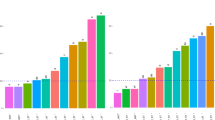

Health risk assessment of penconazole through grape consumption

Grapes have a waxy cuticle that can make it difficult to wash away fungicide residues. This protective layer may also allow certain pesticides to seep into the fruit’s interior. Unlike many other fruits that are peeled before eating, grapes are typically consumed whole, including the skin. This means that people may be more exposed to any residual pesticides that remain on the surface. Therefore, there are serious concerns when people consume grapes contaminated with high levels of penconazole residues on a long-term basis. The results of non-cancer risk to penconazole based on grape intake for teenagers and adults are depicted in the Figure. 3(a-f). As seen in the figure, the 5th percentile, 95th percentile, and mean HQ values for all the studied samples, i.e., unwashed, washed, and disinfected, were < 1, showing no health risk associated with grape consumption containing penconazole for teenagers and adults.

In a previous study in Iran, the hazard quotient of all the studied pesticides, including penconazole, hexaconazole, diazinon, ethion, and phosalone, except diazinon, was lower than one, showing that the health hazard was negligible due to the exposure to these pesticide residues through grape consumption31. In another study, some pesticide residues were detected in some greenhouse products, including cucumber, cantaloupe, and melon sold in Iran. In their study, non-carcinogenic values were less than the safe limit (HQ/HI < 1) in adults and children. But a considerable carcinogenic risk was estimated for the products73. In an earlier study in Iran, levels of flupyradifurone, flupyradifurone and fipronil, and their associated human health risk were investigated. Based on their study, a negligible health risk was estimated for children and adults74. In a recent study in Iran, scientists reported no health hazards for the population of Iran from the consumption of date fruits45. In a study, consumption of fruits containing fungicide levels by the Polish population did not pose dangers to adult and children’s health47. Human health risks associated with the consumption of some vegetables and fruits containing pesticide residues were investigated in Gujarat State of India. They reported that 2.3% of the analyzed vegetables and fruits had pesticide residues above MRLs. However, the determined residue concentrations in samples were within safe limits, and their consumption did not pose any significant health risk to the consumers75. A study was carried out regarding residue concentrations and risk assessment of pesticides in nuts in China. The results showed that there was no significant health risk for the citizens consuming nuts76. In strawberries of China, the non-carcinogenic risk values were below 1, meaning that customers who are exposed to the average pesticide residue levels may not induce significant health risks48.

In many developing countries, effective preventive measures against pesticide residues are often limited due to budget constraints and the lack of strong regulatory frameworks. To reduce human exposure to harmful pesticide residues, it is essential to implement practical, knowledge-based approaches. These strategies include educating farmers about the correct dosage, safe application techniques, and appropriate pre-harvest intervals. Additionally, promoting alternative cropping systems and organic farming practices can make a significant difference. The use of biopesticides and natural pest control methods, combined with improved enforcement of pesticide regulations, can further decrease environmental and health risks.

The findings of this study have important implications for public health and agricultural policy. By quantifying penconazole residues in grapes under various washing scenarios, we provide concrete evidence of the effectiveness of common decontamination methods. The significant reduction in residue levels achieved through washing and disinfection underscores the value of simple, low-cost interventions for consumers.

This study contributes to ongoing efforts to enhance food safety and promote sustainable agriculture by demonstrating a clear link between post-harvest handling practices and reduced pesticide exposure. Our results can guide policymakers, health authorities, and agricultural extension services in designing targeted strategies for pesticide management and public education.

Although this study yields actionable insights for stakeholders, its conclusions should be considered within the context of the following limitations. Detailed information on pesticide spraying practices, such as application dose, formulation, and phenological phase, was not available because gardeners in the study area typically outsource spraying activities to private agricultural companies. Therefore, our assessment was restricted to the actual residue levels present at harvest, rather than a direct evaluation of good agricultural practices. Finally, although a commercial disinfectant was included in the washing experiment to reflect local consumer practices, we did not measure the potential residues of its active biocidal compounds (e.g., benzalkonium chloride). Assessing such residues would require dedicated analytical methods and a separate risk assessment study. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the results, and future research is recommended to address them.

Conclusion

This research paper presents the results of a comprehensive analysis that includes the determination of penconazole residual levels in grapes, a statistical comparison between unwashed and washed methods, and an assessment of the health risks posed to consumers. We aimed to provide valuable insights into pesticide residues in grapes while supporting efforts to ensure food safety and protect public health.

The levels of penconazole found in unwashed grape samples, water-washed samples, and disinfected samples were 0.256 mg/kg (range: 0.154–0.391 mg/kg), 0.195 mg/kg (range: 0.094–0.335 mg/kg), and 0.051 mg/kg (range: 0.027–0.089 mg/kg), respectively. It can be concluded that penconazole residues in grapes grown in Gonabad were within the maximum residue limits (MRLs) proposed by the European Union.

The hazard quotient (HQ) values for all studied samples—unwashed, washed, and disinfected—were all less than 1, indicating negligible health risks associated with the consumption of grapes containing penconazole. Although the levels of penconazole and the associated health risks from grape consumption were determined to be negligible within the studied timeframe, all gardeners and farmers must receive the necessary training and education to ensure the proper and safe application of pesticides. This is crucial for maintaining the safety and well-being of everyone involved, as well as for the integrity of agricultural products.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Taghavi, M., Zarei, A., Darvishiyan, M., Momeni, M. & Zarei, A. Human health risk assessment of trace metals and metalloids concentrations in saffron grown in Gonabad, Iran. J. Food Compos. Anal. 136, 106730 (2024).

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Alami, A., Esmaeili, F. & Zarei, A. Analysis of trace elements in processed products of grapes and potential health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31, 24051–24063 (2024).

Qasemi, M. et al. Human health risk associated with nitrates in some vegetables: A case study in Gonabad. Food Chem. Adv. 4, 100721 (2024).

Mapani, B. et al. Contamination of agricultural products in the surrounding of the Tsumeb smelter complex. In the beginning (1907).

Gelaye, Y. & Negash, B. Residue of pesticides in fruits, vegetables, and their management in Ethiopia. J. Chem. 2024, 9948714 (2024).

Ahmadi, S. & Khazaei, S. Determination of pesticide residues in fruits: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 106012 (2024).

Grewal, A. Pesticide residues in food grains, vegetables and fruits: a hazard to human health. J. Med. Chem. Toxicol. 2(1), 1–7 (2017).

Pham Van, T. Pesticide Use and Management in the Mekong Delta and their Residues in Surface and Drinking Water. Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Bonn (2011).

Ayogu, P., Martins, V. & Gerós, H. Grape berry native yeast microbiota: advancing trends in the development of sustainable vineyard pathogen biocontrol strategies. OENO One 58 (2024).

Huang, Z., Zeng, Q., Li, D. & Li, L. Simultaneous determination of enantiomeric residues of flutriafol, hexaconazole and Diniconazole in fruits and vegetables on a bridged cyclodextrin-based column by HPLC. Microchem. J. 197, 109783 (2024).

Wei, F., Li, X., Lan, B., Song, S. & Guo, Y. Tissue distribution, migration pathways and dietary risk assessment of fungicides in pomelo orchards in South China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 106335 (2024).

Abutaha, M., Fahmy, W., Ahmed, F. & Zaki, K. Exploiting Beneficial Bacterial Functions from Elba Region Via Integrated Combating Plant Pathogens Approaches.

Reddy, G. R., Kumari, D. A. & Vijaya, D. Management of powdery mildew in grape (2017).

Perdichizzi, S. et al. Cancer-related genes transcriptionally induced by the fungicide penconazole. Toxicol. In Vitro. 28, 125–130 (2014).

Dumitriu, G. D., Teodosiu, C. & Cotea, V. V. Management of pesticides from vineyard to wines: focus on wine safety and pesticides removal by emerging technologies. Grapes Wine 1–27 (2021).

Waite, M. B. Fungicides and their Use in Preventing Diseases of Fruits (US Government Printing Office, 1906).

Taft, L. The Use of Poisons as Fungicides and Insecticides. Science (1893).

Waring, R. H., Mitchell, S. C. & Brown, I. Agrochemicals in the food chain. In Present Knowledge in Food Safety. 44–61 (Elsevier, 2023).

Hassan, E., Ahmed, N. & Arief, M. Dissipation and residues of penconazole in grape fruits. World 1, 28–30 (2013).

Babazadeh, S., Moghaddam, P. A., Keshipour, S. & Mollazade, K. Analysis of Imidacloprid and penconazole residues during their pre-harvest intervals in the greenhouse cucumbers by HPLC–DAD. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 17, 1439–1446 (2020).

Yahavi, C. et al. Identification of potential chemical biomarkers of hexaconazole using in vitro metabolite profiling in rat and human liver microsomes and in vivo confirmation through urinary excretion study in rats. Chemosphere 358, 142123 (2024).

Meng, Z. et al. Different effects of exposure to penconazole and its enantiomers on hepatic glycolipid metabolism of male mice. Environ. Pollut. 257, 113555 (2020).

Mercadante, R. et al. Assessment of penconazole exposure in winegrowers using urinary biomarkers. Environ. Res. 168, 54–61 (2019).

Huang, T., Zhao, Y., He, J., Cheng, H. & Martyniuk, C. J. Endocrine disruption by Azole fungicides in fish: A review of the evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 822, 153412 (2022).

Borai, I. H., Atef, A. A., El-Kashoury, A. A., Mohamed, R. A. & Said, M. M. Ameliorative effects of Sesame seed oil against penconazole-induced testicular toxicity and endocrine disruption in male rats. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 14, 10365–10375 (2019).

El-Shershaby, A. E. F. M., Lashein, F. E. D. M., Seleem, A. A. & Ahmed, A. A. Developmental neurotoxicity after penconazole exposure at embryo pre-and post-implantation in mice. J. Histotechnology. 43, 135–146 (2020).

Jia, M. et al. Developmental toxicity and neurotoxicity of penconazole enantiomers exposure on zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Pollut. 267, 115450 (2020).

Turhan, D. O. & Güngördü, A. Developmental, toxicological effects and recovery patterns in xenopus laevis after exposure to penconazole-based fungicide during the metamorphosis process. Chemosphere 303, 135302 (2022).

Penconazole, J. (accessed on 6 May 2016). http://www.inchem.org/documents/jmpr/jmpmono/v92pr14.htm (1992).

EFSA. Conclusion Regarding the Peer Review of the Pesticide Risk Assessment of the Active Substance Penconazole. (accessed on 6 May 2016). http://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/scientific_output/files/main_documents/175r.pdf (2008).

Heshmati, A., Nili-Ahmadabadi, A., Rahimi, A., Vahidinia, A. & Taheri, M. Dissipation behavior and risk assessment of fungicide and insecticide residues in grape under open-field, storage and washing conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122287 (2020).

El-Sheikh, E. S. A. et al. Pesticide residues in vegetables and fruits from farmer markets and associated dietary risks. Molecules 27, 8072 (2022).

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Taghavi, M., Harimi, M. & Zarei, A. Trace elements in commercially available infant formulas in iran: determination and Estimation of health risks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 186, 114588 (2024).

Mahdavi, V., Omar, S. S., Zeinali, T., Sadighara, P. & Fakhri, Y. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment induced by pesticide residues in fresh pistachio in Iran based on Monte Carlo simulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 40942–40951 (2023).

Mohan, S. & Sruthy, S. Human health risk assessment due to solvent exposure from pharmaceutical industrial effluent: deterministic and probabilistic approaches. Environ. Processes. 9, 18 (2022).

Authority, E. F. S. et al. Modification of the existing maximum residue level for penconazole in grapes. EFSA J. 15, e04768 (2017).

IRIPP. Foods of Plant origin—Determination of Pesticide Residues, http://mrl.iripp.ir/UI/Home. (Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection).

Navarro, S. et al. Evolution of chlorpyrifos, fenarimol, metalaxyl, penconazole, and Vinclozolin in red wines elaborated by carbonic maceration of monastrell grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 3537–3541 (2000).

Abd-Alrahman, S. H. & Ahmed, N. S. Dissipation of penconazole in peach, plum, apricot, and mango by HPLC–DAD. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 90, 260–63 (2013).

Abd-Alrahman, S. H. & Ahmed, N. S. Dissipation of penconazole in tomatoes and soil. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 89, 873–876 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. Application and enantioselective residue determination of chiral pesticide penconazole in grape, tea, aquatic vegetables and soil by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 172, 530–537 (2019).

Schusterova, D., Hajslova, J., Kocourek, V. & Pulkrabova, J. Pesticide residues and their metabolites in grapes and wines from conventional and organic farming system. Foods 10, 307 (2021).

Poulsen, M. E., Hansen, H. K., Sloth, J. J., Christensen, H. B. & Andersen, J. H. Survey of pesticide residues in table grapes: determination of processing factors, intake and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. 24, 886–895 (2007).

Batta, Y., Zatar, N. & Sama’neh, S. Quantitative determination of chlorpyrifos and penconazole residues in grapes using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (2005).

Eslami, Z., Mahdavi, V. & Tajdar-Oranj, B. Probabilistic health risk assessment based on Monte Carlo simulation for pesticide residues in date fruits of Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 42037–42050 (2021).

Golge, O. & Kabak, B. Pesticide residues in table grapes and exposure assessment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 1701–1713 (2018).

Lozowicka, B., Hrynko, I., Kaczynski, P., Jankowska, M. & Rutkowska, E. Long-term investigation and health risk assessment of multi-class fungicide residues in fruits. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 25 (2016).

Shao, W. C., Zang, Y. Y., Ma, H. Y., Ling, Y. & Kai, Z. P. Concentrations and related health risk assessment of pesticides, phthalates, and heavy metals in strawberries from Shanghai, China. J. Food. Prot. 84, 2116–2122 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Determination and dietary risk assessment of 284 pesticide residues in local fruit cultivars in Shanghai, China. Sci. Rep. 11, 9681 (2021).

Ssemugabo, C., Bradman, A., Ssempebwa, J. C., Sillé, F. & Guwatudde, D. Pesticide residues in fresh fruit and vegetables from farm to fork in the Kampala metropolitan Area, Uganda. Environ. Health Insights. 16, 11786302221111866 (2022).

Kazar Soydan, D., Turgut, N., Yalçın, M., Turgut, C. & Karakuş, P. B. K. Evaluation of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from the Aegean region of Turkey and assessment of risk to consumers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 27511–27519 (2021).

Park, B. K., Kwon, S. H., Yeom, M. S., Joo, K. S. & Heo, M. J. Detection of pesticide residues and risk assessment from the local fruits and vegetables in Incheon, Korea. Sci. Rep. 12, 9613 (2022).

Szpyrka, E. et al. Evaluation of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from the region of south-eastern Poland. Food Control. 48, 137–142 (2015).

Mebdoua, S. et al. Evaluation of pesticide residues in fruits and vegetables from Algeria. Food Addit. Contaminants: Part. B. 10, 91–98 (2017).

Mwanja, M., Jacobs, C., Mbewe, A. R. & Munyinda, N. S. Assessment of pesticide residue levels among locally produced fruits and vegetables in Monze district, Zambia. Int. J. Food Contam. 4, 1–9 (2017).

Al-Jobair, M. O. Pesticide residues in fruits & and vegetables in the Saudi Arabia Kingdom. J. Food Dairy. Sci. 2, 693–698 (2011).

Neme, K. & Satheesh, N. Review on pesticide residue in plant food products: health impacts and mechanisms to reduce the residue levels in food. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. 8, 55–60 (2016).

Obunadike, C. V. et al. Effect of pesticide residue in food crops on man and his environment. World News Nat. Sci. 44, 192–214 (2022).

Kaushik, G., Satya, S. & Naik, S. Food processing a tool to pesticide residue dissipation–A review. Food Res. Int. 42, 26–40 (2009).

Yang, S. J. et al. Effectiveness of different washing strategies on pesticide residue removal: the first comparative study on leafy vegetables. Foods 11, 2916 (2022).

Polat, B. Reduction of some insecticide residues from grapes with washing treatments. Turkish J. Entomol. 45, 125–137 (2021).

Rodrigues, A. A. Z. et al. Use of Ozone and detergent for removal of pesticides and improving storage quality of tomato. Food Res. Int. 125, 108626 (2019).

Vemuri, S., Rao, C. S., Reddy, H., Swarupa, S. & Anitha, K. K.V. Risk mitigation methods for removal of pesticide residues in tomato for food safety. Int. J. Forestry Hortic. 2, 19–24 (2016).

Andrade, G. C. et al. Effects of types of washing and peeling in relation to pesticide residues in tomatoes. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 26, 1994–2002 (2015).

Vemuri, S. B. et al. Methods for removal of pesticide residues in tomato. Food Sci. Technol. 2, 64–68 (2014).

Cengiz, M. F. & Certel, M. Effects of chlorine, hydrogen peroxide, and Ozone on the reduction of mancozeb residues on tomatoes. Turkish J. Agric. Forestry. 38, 371–376 (2014).

Mirani, B., Sheikh, S., Nizamani, S. & Mahmood, N. Effect of household processing in removal of Lufenuron in tomato. Int. J. Agricultural Sci. Res. 3, 235–244 (2013).

Satpathy, G., Tyagi, Y. K. & Gupta, R. K. Removal of organophosphorus (OP) pesticide residues from vegetables using washing solutions and boiling. J. Agric. Sci. 4, 69–78 (2012).

Tiryaki, O. & Polat, B. Effects of washing treatments on pesticide residues in agricultural products. Gıda Ve Yem Bilimi Teknolojisi Dergisi 1–11 (2023).

Bull, D. A growing problem: pesticides and the Third World poor (1982).

Fadwa, A., Yang, C. & Jack, C. Reduction of pesticide residues in tomatoes and other product. J. Food. Prot. 76, 510–515 (2013).

Rodrigues, A. A. et al. Pesticide residue removal in classic domestic processing of tomato and its effects on product quality. J. Environ. Sci. Health part. B. 52, 850–857 (2017).

Mahdavi, V. et al. Pesticide residues in green-house cucumber, cantaloupe, and melon samples from iran: a risk assessment by Monte Carlo simulation. Environ. Res. 206, 112563 (2022).

Mahdavi, V., Gordan, H., Ramezani, S. & Mousavi Khaneghah, A. National probabilistic risk assessment of newly registered pesticides in agricultural products to propose maximum residue limit (MRL). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 55311–55320 (2022).

Sivaperumal, P., Thasale, R., Kumar, D., Mehta, T. G. & Limbachiya, R. Human health risk assessment of pesticide residues in vegetable and fruit samples in Gujarat state. India Heliyon 8 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Residue levels and risk assessment of pesticides in nuts of China. Chemosphere 144, 645–651 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Fateme Esmaeili for her help with sampling, Alireza Moghaddam for preparing the map. We also extend our gratitude to all who contributed to this work.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Research and Technology Vice Chancellor and the Social Determinants of Health Research Center of Gonabad University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made equal contributions to the study, agreed to authorship, and have read and approved the manuscript. Conceptualization and study design: Roya Peirovi-Minaee, review of literature and drafting: Roya Peirovi-Minaee and Ahmad Zarei, review and editing: Ahmad Zarei, Roya Peirovi-Minaee, Ali Alami, and Mojtaba Afsharnia, field and laboratory work: Roya Peirovi-Minaee and Mojtaba Afsharnia, data analysis: Roya Peirovi-Minaee and Ali Alami.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Zarei, A., Alami, A. et al. Health risk assessment of penconazole fungicide residues in grapes: insights from Monte Carlo simulation. Sci Rep 15, 42476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26649-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26649-y