Abstract

Anthocyanins, a type of flavonoid, are crucial metabolites in most vacuolar plants, significantly contributing to plant coloration and defense responses. Owing to their potent anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties, anthocyanins have gained popularity, with extensive application prospects in the health industries. Although the mechanism underlying anthocyanin accumulation in radish fleshy roots has been explored, the processes governing its accumulation in radish leaves remain largely unexplored. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the genetic regulatory mechanisms underlying anthocyanin accumulation, which is responsible for leaf color in radish. We developed self-crossing, hybrid F1 generations, back-crosses, and F2 generation populations using M17 and RA9 pure-line cultivars with purple and green leaves, respectively. Our findings revealed that the color of radish leaves is determined by nuclear genes, with purple being the semi-dominant trait. In the F2 generation, two populations with extreme traits were selected to construct gene sequencing mixing pools for bulked segregant analysis sequencing. Moreover, combined delta (SNP-index) and delta (Indel-index) analyses identified a 200 kb candidate region on chromosome 7, which contains 39 annotated genes. Gene annotation query and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis demonstrated that 8 genes were highly expressed in M17, while 13 genes were highly expressed in RA9. Among these, MYB114-like, which was specifically expressed in M17, was the only gene that clearly demonstrated a role in anthocyanin synthesis. This result suggests that MYB114-like is likely the primary gene regulating radish leaf color in this candidate region. Overall, our study provides an additional reference for enhancing the regulatory network of anthocyanin synthesis in radish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anthocyanins are a class of water-soluble pigments widely found in nature, responsible for the diverse colors—such as pink, red, purple, and blue— in flowers, vegetables, and fruits. These colors help attract pollinators and facilitate seed dispersal1. Anthocyanins also serve as an important source of natural pigments for humans2. In plants, anthocyanins play special roles in biotic and abiotic stresses3, However, the anthocyanin content in commonly available green leafy vegetables, which are preferred for consumption, is limited. Therefore, cultivating vegetables rich in anthocyanins can, to some extent, better address the growing consumer demand for functional foods.

Anthocyanins belong to the flavonoid subclass, characterized by a C6-C3-C6 carbon skeleton. The most common anthocyanins in nature include cyanidin, delphinidin, pelargonidin, petunidin, peonidin, and malvidin4. Several factors, such as environmental pH and hydroxylation and methylation of the B ring, affect the color and stability of anthocyanins5. The core pathway is largely conserved across studied species6. Specifically, the anthocyanin pathway branches from the general flavonoid pathway, which itself originates from the phenylpropanoid pathway starting with phenylalanine7. Phenylalanine is converted to 4-coumaryl CoA by the catalysis of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL)8, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H)9, and 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4CL)10. Subsequently, chalcone synthase (CHS)11, chalcone isomerase (CHI)12, and flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3H) catalyze the formation of dihydrokaempferol13, which is then converted to dihydroquercetin and dihydromyricetin, the precursors of anthocyanin synthesis, via flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H) and flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3’5’H) catalysis, Dihydroquercetin and dihydromyricetin form colorless leucoanthocyanidins by dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), and colored anthocyanidins are then formed through the action of leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase/anthocyanidin synthase (LDOX/ANS). Finally, glycosyltransferases catalyze the formation of glycoside bonds between anthocyanidins and sugars, resulting in the stable production of anthocyanins4,14.

Several transcription factors regulate anthocyanin synthesis in plants. The protein complex known as MBW, comprising R2R3-MYB, basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and WD40 transcription factors, binds to the promoters of structural genes and plays a key role in the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis15. Colored radishes are also an important source of anthocyanins, with research primarily focusing on the anthocyanin content in fleshy roots. For example, RsMYB1 in radish is homologous to AtPAP1/2 (a key transcription factor controlling anthocyanin synthesis in Arabidopsis), which is a key regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in radish fleshy roots16. A previous study using quantitative trait loci-sequencing identified RsMYB1.1 as a key gene controlling fleshy root purple skin traits in radishes. It also identified three additional homologous genes (RsMYB1.2, RsMYB1.3, and RsMYB1.4) in the radish genome17. Muleke et al. (2021) also reported that the homologous genes AtPAP1/2, RsMYB41, RsMYB117, and RsMYB132 are highly expressed in the fleshy root bark of red radish, whereas RsMYB65 and RsMYB159 are highly expressed in the fleshy root bark of purple radish18. This suggests the involvement of these genes in regulating anthocyanin synthesis in the fleshy root of radish. Furthermore, Lai et al. (2020) demonstrated that the interaction between radish bHLH transcription factors RsTT8 and RsMYB1 positively regulates anthocyanin synthesis in fleshy roots19. At the post-transcriptional regulation level, protein ubiquitination, miRNA, and small interfering siRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene silencing also affect anthocyanin synthesis in radishes. For example, Gao et al. predicted 74 miRNAs involved in the regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in carmine radish20. Epigenetic regulation also plays a role, as the DNA methylation of structural genes in the anthocyanin synthesis pathway and regulatory genes affect anthocyanin synthesis. For example, methylation of the promoter of RsMYB1 leads to the emergence of white meat mutants21. Although these studies have extensively investigated the mechanism of anthocyanin synthesis in radish roots, studies exploring the mechanism of anthocyanin accumulation in leaves are limited.

Radish leaves, an important food source used in pickles, are rich in taste and nutrition. In particular, purple radish leaves are rich in anthocyanins, which are known to exhibit high antioxidant activity. This makes them a promising source of natural colorants and bioactive compounds22. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the regulatory mechanisms underlying the anthocyanin accumulation in the radish leaves. To this end, we used a new assembly of the radish genome sequences23 and performed bulked segregant analysis sequencing (BSA-seq) to identify the genes involved in anthocyanin accumulation in purple radish leaves. We also analyzed the differences in anthocyanin accumulation mechanisms between purple and green leaf radishes. The findings of this study provide important insights into the molecular regulatory network of anthocyanins in radish.

Methods

Plant materials

The pure-bred radish (Raphanus sativus L. var. sativus) varieties M17 and RA9 generated through our breeding program, with purple and green leaves, respectively, were used in this study. Approximately 45-day-old radish seedlings were used to analyze anthocyanins content and gene expression as well as bulk segregant analysis. M17 and RA9 were hybridized to generate the F1 generation and self-crossed to obtain the P1 and P2 generations. Furthermore, the F1 plants were back-crossed with M17 and RA9 to obtain the BC1 and BC2 generation populations, respectively, and then self-crossed to obtain the F2 generation population. Radishes were grown in an open experimental field from mid-September, with a row spacing of 40 ~ 50 cm, at the Nanchong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Sichuan Province.

Anthocyanin content measurement

Forty-five days after sowing, a 1 g fresh leaf sample was collected from the inner part of the third basal leaf. The sample was thoroughly ground in liquid nitrogen, and a 4 mL anthocyanin extractant (80% methanol containing 5%HCl) was added. The mixture was soaked overnight at 4℃. Anthocyanin content was measured following a previously described method24. Briefly, the absorption values were measured using a spectrophotometer (OD-1000+, One Drop, New York, NY, USA) at wavelengths of 530, 620, and 650 nm, and the optical density value (ODλ) was calculated using the following formula:

ODλ = (OD530-OD620) − 0.1 × (OD650-OD620)

Subsequently, the anthocyanin content was measured using the following formula:

anthocyanin content (nmol/g) = ODλ/ ε × V/m × 106

where ε is the molar extinction coefficient of anthocyanin 4.62 × 106, V is the total volume of extract solution (mL), and m is the sampling weight (g).

Phenotyping and DNA extraction

Seedlings that had been growing for approximately 45 days were used for phenotypic observation, distinguished by their true leaf color. In the F1 generation, the real leaf colors alternated between purple and green. In contrast, the F2 generation exhibited two extreme traits: complete purple and complete green leaf colors. For DNA extraction, radish leaves were collected after approximately 6 weeks of growth, when the color of the leaves was distinct. The leaf samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder. Genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method25, and the DNA quality was assessed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The concentration of extracted DNA was measured using an ultramicrospectrophotometer (OD-1000+, NanoDrop).

Bulk segregant analysis

The bulk segregant analysis refers to the work of Ding et al.26. Briefly, a DNA mixing pool was constructed by pooling the DNA samples collected from 26 purple (Rpool) and green-leaved (Gpool) F2 plants.Qualified genomic DNA was mechanically sheared by ultrasonication. The fragmented DNA was then purified, end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated with sequencing adapters. Libraries were constructed from sheared DNA fragments size-selected to approximately 350–500 bp (including adapters) using agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by PCR amplification to generate the final sequencing library. Four samples of Gpool, Rpool, and two parental lines, Gp and Rp, were used for paired-end (150 bp) sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq platform based on Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The quality of the raw reads obtained by sequencing was assessed by fastp(v0.20.0)27. Clean reads were obtained by filtering out the reads with the unknown number of bases N > 5 and those with 50% of the length of reads with base mass values < 5. Clean reads were then compared with the reference genome GWHCBIT0000000023 sequences by BWA(v0.7.17-r1188)28, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small indels were identified by GATK (v3.7-0-gcfedb67)29, the SNPs and Indels were annotated based on the comparison results. SNPs meeting the criteria were screened, and the SNPs of Gpool were subtracted from those of Rpool to obtain the delta (SNP-index) value for each site. Similarly, the delta (Indel-index) for each site was calculated. A loss fitting analysis of delta (SNP-index) and delta (SNP-index) values for trusted SNP/indel tags was conducted, and the delta (SNP-index) fitting values were sorted from largest to smallest. The top 1% of the fitted SNP-index values were identified as the loci associated with traits. The identified sites were grouped by size; if the distance between sites was less than 100 kb, the sites were fused into a region. Subsequently, the fused regions were compared to Non-Redundant (NR)30, Swiss Protein Database (SwissProt)31, Gene Ontology (GO)32, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG)33, eukaryotic Clusters of Orthologous Groups (KOG)34, Protein Families Database (Pfam)35, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)36 using BLASTall (version 2.2.26)37 software to obtain the best comparison results (e-value is 10− 5) and functional information of genes within the regions, followed by enrichment analysis of these genes, in which, KEGG pathway analysis was performed using the KEGG database38,39,40.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) of candidate genes

The real leaves of M17 and RA9 seedlings growing for about 45 days were used to extract RNA, and total RNA was extracted using an RNAiso Plus kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using an M-MLV kit (Promega, Madsion, WI, USA) and stored at − 20℃ for further use. qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96™Real-Time instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, MA, USA), and the reaction system was configured according to the instructions of GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega). RsActin (Rsa4g054100) was used as the internal reference17, and the relative expression of the target genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method41. qRT-PCR of each sample was performed with at least three biological replicates. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Data analysis

The chi-square test was used to calculate the proportion of plant segregation in each generation using the SPSS software. For the analysis of the significant difference between the data, two-tailed student’s t-tests were performed using the SPSS software compared to control. Data are presented as the mean ± SE.

Results

The F2 generation resulting from the hybridization of RA9 and M17 showed a clear segregation of traits

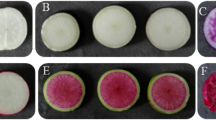

In this study, we used M17 and RA9, which are two pure lines with contrasting real leaf color, purple and green, the content of anthocyanins in purple leaves is about twice that of green leaf varieties, but no discernible difference in fleshy roots or plant height and width (Fig. 1A,B, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). To investigate the genetic mechanism responsible for this leaf color, we obtained different generation populations (selfed, F1, F2, BC1, and BC2) and observed distinct character separation into three groups in the F2 generation —purple, pale purple, and green (Fig. 1C). Measurement of the anthocyanin content in these groups revealed that the anthocyanin content was highest in purple leaves, followed by lavender, and lowest in green leaves (Fig. 1D).

Leaf color and anthocyanin content of M17, RA9 and the F2 generation plants. Purple leaves of M17 and green leaf of RA9 (A). Leaf anthocyanin content of RA9 and M17 (B). F2 generation plants with purple, pale purple, and green leaves (C). Leaf anthocyanin content of three types of F2 generation plants (D). ** p < 0.01; two-tailed t-test; data represents the mean ± SE, Bar in the figure represents 1 cm.

Inheritance of the leaf color in radishes

To further clarify the genetic rules of radish leaf color, we conducted self-crosses and reciprocal crosses between M17 and RA9. The 2471 self-crossed offspring of M17 had purple leaves, while the 2144 self-crossed offspring of RA9 had green leaves (Table 1). In the reciprocal crosses, 1355 and 1020 offspring were pale purple-leaved when M17 was used as the male and female parent, respectively (Table 1). This result indicates that the gene controlling leaf color is located in the nucleus rather than in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, by back-crossing the F1 plants with M17, we obtained 1461 offspring, of which 714 had purple and 747 had pale purple leaves. Among the back-cross offspring with RA9, 929 and 984 of 1913 progenies were light red and green, respectively (Table 1). Statistical analysis of the F2 generation population demonstrated that a total of 2383 offspring were produced in F2, of which 585 had purple, 1178 pale purple, and 620 had green leaves (Table 1). The Chi-square test indicated consistency with the Mendelian law of gene segregation. These findings indicate that the gene controlling the purple color of radish leaves is located in the nucleus and that the purple trait is inherited in a semi-dominant manner.

BSA analysis indicates that the candidate genes for leaf color were located on chromosome 7 within 200 Kb

A total of 72.66 Gb of clean reads were generated by sequencing the four samples: Rpool (F2 generation extreme purple leaf mixing pool), Gpool (F2 generation extreme green leaf mixing pool), Gp (RA9), and Rp (M17), with Q30 values exceeded 90.02%. The comparison efficiency between these four samples and the reference genome sequence was at least 98.19%, the average coverage depth was at least 38.84 ×, and genome sequence coverage was 87.41% (at least one base coverage). Compared with the reference genome GWHCBIT00000000 sequence, Gp, Gpool, Rp, and Rpool detected 2,518,278, 2,937,522, 2,541,916, and 2,956,432 SNPs, respectively. We analyzed the SNPs between Gpool and Rpool. Delta (SNP-index) correlation analysis revealed that the candidate regions related to purple leaf traits were located in the 0.27 M region from 9,626,155 to 9,891,580 on chromosome 7 (Fig. 2A), which comprises a total of 39 genes (Supplementary Table 3). We further analyzed the small indels in these two mixed pools in the same manner. The delta (Indel-index) association method revealed that the candidate region related to purple leaf traits was located in the 0.46 M region from 9,387,306 to 9,854,654 on chromosome 7 (Fig. 2B) and contained 61 genes. To refine the range of candidate genes, we narrowed the candidate region to the intersection of these two regions, with a total of 39 genes (Supplementary Table 3).

The delta (SNP-index) and delta (Indel-index) distributions of the whole genome of radish analyzed using BSA. Delta (SNP-index) (A) and delta (Indel-index) distribution (B). The scatter points in the figure indicate the calculated values of delta (SNP-index) and delta (Indel-index). The black curve represents the corresponding fitting value. The red dashed line represents a threshold line with a fitting value of 99%. The region above the 99% threshold line (red) was selected as the candidate region associated with the trait. Gpool: green leaf radish mixing pool, Rpool: purple leaf radish mixing pool, red star represents BSA association interval.

Annotation of the genes identified in the candidate region

We annotated the genes in the BSA association region were using the GO database and classified them into three categories: cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes. In the category of cellular components, most genes were annotated into the cell and cell parts subclasses. In terms of molecular function, they were mainly distributed in the subclasses of binding and catalytic activity. In biological processes, they were mainly classified into metabolic and cellular processes (Fig. 3A). In the COG annotation analysis, genes from the candidate regions involved in general function prediction accounted for the highest frequency, followed by signal transduction mechanisms and transcription (Fig. 3B). We further performed KEGG annotation and enrichment analysis on these candidate genes. A total of 13 genes were annotated across five categories: cellular processes, environmental information processing, genetic information processing, metabolism, and organismal systems. The first three subclasses with the highest number of distributed genes were translation, carbohydrate metabolism, and metabolism of other amino acids (Fig. 3C). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of these associated genes demonstrated that the top five enriched pathways were RNA transport, plant–pathogen interaction, peroxisomes, mRNA surveillance pathway, and MAPK signaling pathway (Fig. 3D).

qRT-PCR analysis of genes in the candidate region

We performed qRT-PCR analysis on the genes in the candidate region to clarify the expression patterns of these genes in M17 and RA9 and identify genes associated with the purple leaf phenotype. Among the 39 genes, excluding those whose expression levels were too low to be amplified, we obtained quantitative results for 24 genes (Fig. 4). Except for the expression of three genes—namely Rsa7g018180 (MYB20), Rsa7g018320 (ABC1K15), and Rsa7g018360 (hypothetical protein)—the expression of the remaining 21 genes differed significantly between the two cultivars. Specifically, eight genes, Rsa7g018060 (FRK3/6), Rsa7g018080 (CAML), Rsa7g018100 (MYB114-like), Rsa7g018110 (CAR2), Rsa7g018240 (ZFP4), Rsa7g018250 (ZFP4), Rsa7g018340 (ABC1K15), and Rsa7g018380 (SD1-6), were highly expressed in M17. In particular, the expression of Rsa7g018100 (anthocyanin-regulating MYB transcription factor, MYB114-like) and Rsa7g018110 (CAR2) was higher (> 4.5 times) in M17 than in RA9. Thirteen genes, namely Rsa7g018020 (PCFS5), Rsa7g018090 (CML24), Rsa7g018120 (ETR1), Rsa7g018130 (AAF), Rsa7g018140 (ALY3), Rsa7g018230 (TMK1), Rsa7g018260 (hypothetical protein), Rsa7g018270 (EIF3J), Rsa7g018290 (NMD3), Rsa7g018310 (GAD2), Rsa7g018330 (GAD2), Rsa7g018350 (CICDH), and Rsa7g018370 (AAE12) were highly expressed in RA9 compared to M17. In particular, the expression of Rsa7g018020 (PCFS5), Rsa7g018090 (CML24), Rsa7g018310 (GAD2), and Rsa7g018330 (GAD2) was higher in RA9 (> 3 folds) than in M17.

qRT-PCR analysis of anthocyanins synthesis structure genes

To further analyze the expression of anthocyanin-synthesizing structural genes in M17, we validated our results using qRT-PCR. As presented in Fig. 5, key structural genes—RsPAL4, Rs4CL4, RsCHS, RsCHI, RsF3H, RsDFR, RsANS, and RsUFGT—involved in anthocyanin synthesis, were significantly and highly expressed in M17. In particular, the expression levels of genes involved in late stable anthocyanin synthesis, RsANS, RsDFR, and RsUFGT, was 12-fold higher in M17 than in RA9. These results indicate that the regulatory mechanism of candidate genes is related to the expression changes of these genes.

Discussion

Characterization of candidate genes for purple leaf trait in radish leaf

In this study, we demonstrated that the gene controlling radish leaf color is located in a 200 kb region on chromosome 7, which contained 39 genes, indicating that they may perform multiple functions. To further clarify the correlation between these genes and purple leaf traits, we performed qRT-PCR, which revealed a slight amplification of 15 genes, indicating that these genes may not be involved in regulating the color of radish leaves. Among the remaining 24 genes, the expression levels of three genes—MYB20, ABC1K15, and Rsa7g018360 (encoding a hypothetical protein)—did not differ between the leaves of the two cultivars. In Arabidopsis thaliana, MYB20 regulates the expression of phenylalanine and phenylalanine-derived lignin synthesis genes, thereby affecting the formation of secondary cell walls42. In contrast, peach flowers, PpMYB20 plays a negative role in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation43. These contrasting roles highlight the functional diversity among MYB family members in modulating flavonoid biosynthesis pathways. ABC1K15 belongs to an ancient family of atypical kinases localized in mitochondria and has been implicated in plant oxidative stress responses, though its precise biological roles remain unclear44. In the present study, the two radish genes annotated as ABC1K15 were Rsa7g018320 and Rsa7g018340. The sequences of these two genes were highly similar, with a sequence identity of 88.96% (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the gene has two loci in the candidate region. However, the expression level of Rsa7g018340 in M17 was slightly higher than that in RA9. This increased expression may result from the distinct expression patterns of the homologous genes. Nevertheless, the function of this gene in anthocyanin synthesis requires further experimental verification.

Among the genes highly expressed in m17 within the BSA candidate region, RsMYB114-like is associated with anthocyanin synthesis

In addition to Rsa7g018340, seven other genes were also highly expressed in M17: Rsa7g018060 (FRK3/6), Rsa7g018080 (CAML), Rsa7g018100 (MYB114-like), Rsa7g018110 (CAR2), Rsa7g018240 (ZFP4), Rsa7g018250 (ZFP4), and Rsa7g018380 (SD1-6). FRK3/6 is involved in the formation of oil in seeds and has been speculated to be a target of transcription factor WRI1 involved in the sugar-to-fatty acid conversion process45,46. The increase in the expression of this gene in M17 may be due to the increase in the synthesis of secondary metabolites such as anthocyanin, which prompts the primary metabolism to provide precursors47. The increased expression of Rsa7g018080 (CAML) in M17 reflects an increase in intracellular calcium signaling during anthocyanin synthesis48. However, the detailed functionality of this gene is unclear. The positive function of Rsa7g018100 (anthocyanin-regulating MYB transcription factor, MYB114-like), which is highly expressed in M17, in regulating anthocyanin synthesis has been validated in several species, For example, in pears, PyMYB114 acts as a direct target of the anthocyanin synthesis inhibitor PyERF9, inhibiting anthocyanin synthesis by blocking PyMYB114 expression via histone deacetylation49. Another pear ERF transcription factor, PyERF3, interacts with PyMYB114 and co-regulates pear anthocyanin biosynthesis with PybHLH350. PyMYB114 also acts synergistically with the PyWRKY factor, resulting in anthocyanin accumulation in red pear51. Moreover, MYB114 plays a role in promoting anthocyanin accumulation in lilies52. In rose, RhMYB114a alone or in combination with RhbHLH3 activates transcription of anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes, such as RhCHS, RhF3’H, RhANS, and RhGT1 to promote anthocyanin synthesis53. This result suggests that the positive function of MYB114 in anthocyanin synthesis appears to be similar in plants.

MYB family transcription factors regulate gene expression through direct or indirect mechanisms54, including the control of anthocyanin biosynthesis55,56, Among them, MYB114 has recently been shown to directly target structural genes in the anthocyanin pathway53, In this study, we found that expression of several anthocyanin structural genes—including those previously reported as targets of MYB114—was significantly elevated in M17. This suggests that the RsMYB114-like gene may regulate these structural genes in radish. However, direct targets of RsMYB114-like in radish leaves require further experimental validation. Rsa7g018110 (CAR2) also exhibits high expression levels in M17; it positively regulates the abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway57 and has been proposed as a potential hub linking ABA signaling and anthocyanin biosynthesis. Rsa7g018240 and Rsa7g018250 are homologous to the Arabidopsis genes encoding ZFP4, a multifunctional protein, and play a role in seed germination58, cell differentiation, plant nutritional development, vegetative growth, and root hair development59. However, their specific function in anthocyanin synthesis remains to be explored. Rsa7g018380 (SD1-6) has been speculated to play a role in plant sexual reproduction60; however, understanding its other specific functions requires more in-depth research. Among these highly expressed genes in M17, only MYB114-like has been directly linked to anthocyanin synthesis based on current evidence.

The expression levels of 13 genes were lower in M17 than in RA9

In this study, five genes (Rsa7g018020, Rsa7g018090, Rsa7g018260, Rsa7g018310, and Rsa7g018330) exhibited significantly reduced expression in M17 leaves—less than one-third of that in RA9. Rsa7g018020 encodes PCFS5 protein, including mRNA polyadenylation, which can influence gene expressio61. Although its downregulation in M17 suggests a possible repressive role in anthocyanin synthesis, further functional validation is required. Rsa7g018090 encodes a calmodulin-like protein (CML24), known to participate in abiotic stress responses62. The expression of this gene in M17 contrasts with that of Rsa7g018080 (CAM1), suggesting that CAM1 is more advantageous in the anthocyanin synthesis process. Rsa7g018260 is an unknown protein in radish, and its low expression in M17 cells suggests that it may negatively regulate anthocyanin synthesis. However, the specific mechanism remains unclear. Rsa7g018310 and Rsa7g018330 are homologous to genes encoding glutamate decarboxylase 2 (GAD2) in Arabidopsis thaliana, an important protein in glutamate metabolism that catalyzes the conversion of glutamate to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in living organisms. Reduced GAD2 expression may limit glutamate metabolism, potentially promoting anthocyanin synthesis, as observed in other species such as apple63. Additionally, three genes—Rsa7g018120 (ETR1), Rsa7g018290 (NMD3), and Rsa7g018350 (CICDH)— exhibited approximately half the expression levels in M17 compared to RA9. The downregulation of ETR1 expression in M17 reflects the negative function of ethylene signaling during anthocyanin accumulation in radishes, as reported in pears49,64. NMD3 protein is involved in the nuclear export of the 60 S ribosomal subunit and the formation of the secondary cell wall. However, its role in anthocyanin accumulation has not been studied65. CICDH is a NADP+-isocitrate dehydrogenase, which contributes to NADPH production under oxidative stress. Low levels of CICDH expression in M17 may be attributed to the antioxidant activity of anthocyanins. The remaining genes, Rsa7g018130, Rsa7g018140, Rsa7g018230, Rsa7g018270, and Rsa7g018370, were only slightly less expressed in M17 than in RA9. These genes are annotated to those encoding senescence-associated protein (AAF), THO complex subunit 4 C (ALY3), receptor protein kinase TMK1, translation initiation factor EIF3 subunit (EIF3J), and probable acyl-activating enzyme 12 (AAE12), respectively. AAF is a protein related to leaf senescence, and its involvement in the regulation of leaf senescence is mediated by age and stress factors during A. thaliana development, thereby contributing to redox homeostasis66. The low expression of AAF in M17 may also be due to the antioxidant activity of high anthocyanins in M17. ALY3 is an RNA-binding protein involved in the transportation of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm67; however, its role in anthocyanin synthesis is unknown. TMK1 is a key regulator in auxin signaling, and its low expression in M17 suggests a negative regulatory function of auxin signaling during anthocyanin synthesis, as previously reported68. Rsa7g018370 was annotated to EIF3J, a eukaryotic translation initiation factor; however, no functional study of this gene has been reported yet. AAE12 is an acyl-activating enzyme, and its role in anthocyanin synthesis remains to be verified. And the function of these genes that are highly expressed in RA9 requires further experimental verification.

RsMYB114-like may be a key gene in the regulation of radish leaf anthocyanin accumulation

Collectively, the findings of this study demonstrated that only Rsa7g018100 (RsMYB114-like) has a clear function in anthocyanin synthesis. However, further verification is needed to understand how it functions in radish leaves and whether its function differs from that in other plants. Although the expression of key anthocyanin synthesis regulation genes is upregulated in M17, further experimental verification is required to determine whether the structural RsMYB114-like target genes in radish are the same as those in other plants, or whether it targets a single gene or multiple genes in radish leaves. Furthermore, the expression of some genes, such as Rsa7g018020 (PCFS5), Rsa7g018110 (CAR2), Rsa7g018310 (GAD2), and Rsa7g018330 (GAD2), demonstrated considerable differences between the two varieties. These differences may be related to different metabolic processes and cell activities in the two varieties and may be associated with hormone signaling affecting anthocyanin synthesis. However, the exact mechanisms require experimental verification.

Conclusions

Although anthocyanin research in radish has primarily focused on fleshy roots, leaves—an important food source—remain understudied. The purple-leafed variety M17 accumulates high levels of anthocyanins, offering enhanced antioxidant activity and commercial potential. To explore the genetic basis of this trait, we conducted BSA-seq in F₂ population from a M17 × RA9 cross and mapped the candidate locus to a 200 kb region on chromosome 7 containing 39 genes. Among these, Rsa7g018100, encoding an MYB114-like transcription factor, emerged as a key candidate based on its known role in anthocyanin biosynthesis. M17 exhibited upregulated expression of multiple anthocyanin pathway genes, and the strong correlation between RsMYB114-like expression and pigment accumulation suggests its regulatory role in leaf coloration. Our findings provide initial genetic insights into radish leaf pigmentation and support marker-assisted breeding for improved quality traits.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, and the Illumina raw data of BSA were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at NCBI under BioProject number PRJNA1164153 under the following link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1164153.

References

Zhang, Y. J. et al. Advances in epigenetic modification affecting anthocyanin synthesis. Yi chuan = Hereditas. 44 (12), 1117–1127. https://doi.org/10.16288/j.yczz.22-171 (2022).

Sankaralingam, B., Balan, L., Chandrasekaran, S. & Muthu Selvam, A. Anthocyanin: A natural dye extracted from hibiscus Sabdariffa (L.) for textile and dye industries. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 195 (4), 2648–2663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-03815-w (2023).

Kaur, S. et al. Protective and defensive role of anthocyanins under plant abiotic and biotic stresses: an emerging application in sustainable agriculture. J. Biotechnol. 361, 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2022.11.009 (2023).

Alappat, B. & Alappat, J. Anthocyanin pigments: beyond aesthetics. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 25 (23). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25235500 (2020).

Zhao, Y. W., Wang, C. K., Huang, X. Y. & Hu, D. G. Anthocyanin stability and degradation in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 16 (12), 1987767. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2021.1987767 (2021).

Tanaka, Y., Sasaki, N. & Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: anthocyanins, betalains and carotenoids. Plant. J. 54 (4), 733–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03447.x (2008).

Winkel-Shirley, B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant. Physiol. 126 (2), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.126.2.485 (2001).

Koukol, J. & Conn, E. E. The metabolism of aromatic compounds in higher plants. IV. Purification and properties of the phenylalanine deaminase of hordeum vulgare. J. Biol. Chem. 236, 2692–2698 (1961).

Russell, D. W. & Conn, E. E. The cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase of pea seedlings. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 122 (1), 256–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(67)90150-6 (1967).

Sütfeld, R. & Wiermann, R. Die bildung von coenzym A-thiolestern verschieden substituierter zimtsäuren durch enzymextrakte Aus antheren. Z. für Pflanzenphysiologie. 72 (2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-328X(74)80126-1 (1974).

Ferrer, J. L., Jez, J. M., Bowman, M. E., Dixon, R. A. & Noel, J. P. Structure of chalcone synthase and the molecular basis of plant polyketide biosynthesis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 (8), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1038/11553 (1999).

Reuber, S., Jende-Strid, B., Wray, V. & Weissenböck, G. Accumulation of the chalcone isosalipurposide in primary leaves of barley flavonoid mutants indicates a defective chalcone isomerase. Physiol. Plant. 101 (4), 827–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb01070.x (1997).

Xiong, S. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Flavanone 3-Hydroxylase gene from Artemisia annua L. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 105, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.04.005 (2016).

He, F. et al. Biosynthesis of anthocyanins and their regulation in colored grapes. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 15 (12), 9057–9091. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15129057 (2010).

Gonzalez, A., Zhao, M., Leavitt, J. M. & Lloyd, A. M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant. J. 53 (5), 814–827. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03373.x (2008).

Ai, T. N., Naing, A. H., Arun, M., Jeon, S. M. & Kim, C. K. Expression of RsMYB1 in Petunia enhances anthocyanin production in vegetative and floral tissues. Sci. Hort. 214, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.11.016 (2017).

Liu, T. et al. Combined QTL-Seq and traditional linkage analysis to identify candidate genes for purple skin of radish fleshy taproots. Front. Genet. 10, 808. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00808 (2019).

Muleke EMm, Wang, Y. et al. Liu L-w: Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of MYB transcription factor genes in radish (Raphanus sativus L). J. Integr. Agric. 20 (1), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63308-1 (2021).

Lai, B. et al. Differential anthocyanin accumulation in radish taproot: importance of RsMYB1 gene structure. Plant Cell Rep. 39 (2), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-019-02485-z (2020).

Gao, J., Peng, H., Chen, F., Luo, M. & Li, W. Genome-wide analysis of transcription factors related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in Carmine radish (Raphanus sativus L.) fleshy roots. PeerJ. 7, e8041. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8041 (2019).

Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Sun, H., Sun, L. & Zhang, L. Transposon-induced methylation of the RsMYB1 promoter disturbs anthocyanin accumulation in red-fleshed radish. J. Exp. Bot. 71 (9), 2537–2550. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eraa010 (2020).

Fang, J. Bioavailability of anthocyanins. Drug Metab. Rev. 46 (4), 508–520. https://doi.org/10.3109/03602532.2014.978080 (2014).

Xu, L. et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) reveals insights into genome adaptation and differential bolting regulation. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 21 (5), 990–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.14011 (2023).

Gou, J. Y., Felippes, F. F., Liu, C. J., Weigel, D. & Wang, J. W. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant. cell. 23 (4), 1512–1522. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.111.084525 (2011).

SpringerNM Isolation of plant DNA for PCR and genotyping using organic extraction and CTAB. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010 (11), pdbprot5515. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot5515 (2010).

Ding, Y. et al. Multi-omics analysis revealed the AGR-FC.C3 locus of brassica Napus as a novel candidate for controlling petal color. Plants (Basel Switzerland). 13 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13040507 (2024).

Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using Fastp. iMeta. 2 (2), e107. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.107 (2023).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25 (14), 1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20 (9), 1297–1303. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.107524.110 (2010).

Deng, Y. Y. et al. Integrated Nr database in protein annotation system and its localization. Comput. Eng. 32, 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1109/infocom.2006.241 (2006).

Bairoch, A. & Apweiler, R. J. N. A. R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its supplement trembl in 1999. Nucleic Acids Res. 1, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.45 (1999).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25 (1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Tatusov, R. L., Galperin, M. Y., Natale, D. A. & Koonin, E. V. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 33–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.33 (2000).

Tatusov, R. L. et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinform. 4 (1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-4-41 (2003).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: the protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (D1), D412–D419. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa913 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S., Okuno, Y. & Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for Deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (Database issue), D277–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh063 (2004).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 (17), 3389–3402. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 (1997).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28 (11), 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

LivakKJ (ed Schmittgen TD) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25 (4), 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Geng, P. et al. MYB20, MYB42, MYB43, and MYB85 regulate phenylalanine and lignin biosynthesis during secondary cell wall formation. Plant Physiol. 182 (3), 1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.19.01070 (2020).

Zhou, H. et al. Multiple R2R3-MYB transcription factors involved in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in Peach flower. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1557. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01557 (2016).

Qin, X. et al. ABC1K10a, an atypical kinase, functions in plant salt stress tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 20 (1), 270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02467-4 (2020).

Kuczynski, C., McCorkle, S., Keereetaweep, J., Shanklin, J. & Schwender, J. An expanded role for the transcription factor WRINKLED1 in the biosynthesis of triacylglycerols during seed development. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 955589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.955589 (2022).

Stein, O. et al. Corrigendum: Arabidopsis fructokinases are important for seed oil accumulation and vascular development. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00303 (2017).

Erb, M. & Kliebenstein, D. J. Plant secondary metabolites as Defenses, Regulators, and primary metabolites: the blurred functional trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 184 (1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.20.00433 (2020).

Shin, D. H. et al. Calcium dependent sucrose uptake links sugar signaling to anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 430 (2), 634–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.100 (2013).

Ni, J. et al. The ethylene-responsive transcription factor PpERF9 represses PpRAP2.4 and PpMYB114 via histone deacetylation to inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis in Pear. Plant. cell. 35 (6), 2271–2292. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koad077 (2023).

Yao, G. et al. Map-based cloning of the Pear gene MYB114 identifies an interaction with other transcription factors to coordinately regulate fruit anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant. Journal: cell. Mol. Biology. 92 (3), 437–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13666 (2017).

Li, C. et al. PyWRKY26 and PybHLH3 cotargeted the PyMYB114 promoter to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis and transport in red-skinned Pears. Hortic. Res. 7, 37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-020-0254-z (2020).

Fang, S. et al. LhANS-rr1, LhDFR, and LhMYB114 Regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in flower buds of Lilium ‘Siberia’. Genes. 14 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14030559 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Light-mediated anthocyanin biosynthesis in Rose petals involves a balanced regulatory module comprising transcription factors RhHY5, RhMYB114a, and RhMYB3b. J. Exp. Bot. 74 (18), 5783–5804. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erad253 (2023).

Li, C., Yu, W., Xu, J., Lu, X. & Liu, Y. Anthocyanin biosynthesis induced by MYB transcription factors in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231911701 (2022).

Stracke, R., Werber, M. & Weisshaar, B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 4 (5), 447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00199-0 (2001).

Dubos, C. et al. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 15 (10), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005 (2010).

Rodriguez, L. et al. C2-domain abscisic acid-related proteins mediate the interaction of PYR/PYL/RCAR abscisic acid receptors with the plasma membrane and regulate abscisic acid sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant. cell. 26 (12), 4802–4820. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.114.129973 (2014).

Joseph, M. P. et al. The Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN3 interferes with abscisic acid and light signaling in seed germination and plant development. Plant Physiol. 165 (3), 1203–1220. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.234294 (2014).

Benyó, D. et al. The zinc finger protein 3 of Arabidopsis Thaliana regulates vegetative growth and root hair development. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1221519. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1221519 (2023).

Sankaranarayanan, S., Jamshed, M., Delmas, F., Yeung, E. C. & Samuel, M. A. Identification and characterization of a female gametophyte defect in sdk1-7 +/- abi3-6 +/- heterozygotes of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 15 (8), 1780038. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2020.1780038 (2020).

Hunt, A. G. et al. Arabidopsis mRNA polyadenylation machinery: comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions and gene expression profiling. BMC Genom. 9, 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-220 (2008).

Zhu, X. et al. Calmodulin-like protein CML24 interacts with CAMTA2 and WRKY46 to regulate ALMT1-dependent al resistance in Arabidopsis Thaliana. New Phytol. 233 (6), 2471–2487. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17812 (2022).

Wang, L., Wang, Z., Li, Z. & Zhu, Y. Promotion of L-glutamic acid on anthocyanin accumulation of Fuji apples. J. Fruit Sci. (02), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.2006.02.001 (2006).

Sun, H., Hu, K., Wei, S., Yao, G. & Zhang, H. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTORS 4.1/4.2 with an EAR motif repress anthocyanin biosynthesis in red-skinned Pears. Plant Physiol. 192 (3), 1892–1912. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiad068 (2023).

Chen, M. Q. et al. Arabidopsis NMD3 is required for nuclear export of 60S ribosomal subunits and affects secondary cell wall thickening. PloS One. 7 (4), e35904. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035904 (2012).

Chen, G. H., Liu, C. P., Chen, S. C. & Wang, L. C. Role of ARABIDOPSIS A-FIFTEEN in regulating leaf senescence involves response to reactive oxygen species and is dependent on ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2. J. Exp. Bot. 63 (1), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/err278 (2012).

Pfaff, C. et al. ALY RNA-Binding proteins are required for nucleocytosolic mRNA transport and modulate plant growth and development. Plant Physiol. 177 (1), 226–240. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.18.00173 (2018).

LaFountain, A. M. & Yuan, Y. W. Repressors of anthocyanin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 231 (3), 933–949. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17397 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sichuan Natural Science Foundation Project, Nanchong Science and Technology Plan Project, and Nanchong City Academy of Agricultural Sciences Youth Science and Technology Fund Project, grant numbers 2023NSFSC1246, 23YYJCYJ0009, and QJZD2402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, Q.P., Q.G., S. S.; methodology, Q.P., S. Y., Z. H., S. S.; software, Z. H., L. G.; validation, Q.P., Z. H., X. F., T. Z., P. Y., L. L., L. G., C. X.; investigation, Q.P., T. Z.; resources, Q.P., X. F., L. L.; data curation, L.Z., T. Z., P. Y., L. G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.P., S. S.; writing—review and editing, Q.P., Q.G., L.Z.; visualization, Q.P., Z. H., L. G.; supervision, X. F.; project administration, S. Y., Z. H.; funding acquisition, C. X.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pu, Q., Yang, S., He, Z. et al. Identification of regulatory genes involved in anthocyanin accumulation in radish leaves using bulk segregant analysis. Sci Rep 15, 42455 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26681-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26681-y