Abstract

We implement a framed field experiment to understand and rationalize previous contradictory calorie labeling findings showing mostly decreasing or null effects, but also some evidence of increasing calorie intake. Our study suggests that the numeric value of calorie information alone is not sufficient to explain the impact of information on food choice, but it is the gap between an individual calorie reference point expectation and the realized actual amount that influences food choices. We manipulate this gap in a carefully controlled experiment creating meals that look nearly identical but substantially differ in their calorie content. There is a sharp contrast in the literature with a large body of research only examining the effect of providing the calorie content for a meal while ignoring individual consumers’ expectations. Understanding the underlying mechanism driving calorie information response is crucial for designing and implementing effective calorie interventions and policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2018, the Food and Drug Administration mandated a menu labeling law targeting chain restaurants with 20 or more locations to disclose the number of calories on their menus. Since then, research on the effect of displaying caloric content on food choice has exploded1. Unfortunately, the results are far from reaching a consensus. Although some studies report that displaying calories in restaurant menus effectively reduces food intake2,3,4, others find null effects5,6,7,8, and9 report increased calorie intake. In this article, we propose a simple framework to understand and rationalize these contradictory findings in the literature and test it empirically using a framed field experiment. Understanding the forces driving the intended policy effects is crucial for the design and implementation of effective calorie interventions.

Our framework suggests that calorie information alone is not sufficient to influence food choice. Decision makers have an unobserved individual reference point for the meals based on their calorie expectations, previous experience, and individual-specific metabolic factors such as age, height, weight, gender, physical activity, body image concerns, and other factors. The decision-maker forms individual-specific reference point expectations for the calorie amount of a meal. We assume calorie utility follows a quadratic function centered at the reference point. This assumption implies people prefer to eat more calories, but there is a negative effect to overeating calories beyond the reference point threshold due to biological and psychological factors (i.e., overconsumption guilt, physical discomfort or even sickness). That is, deviations from the optimal reference point reduce calorie utility. When the calorie content of a meal is below (above) the reference point, people prefer to eat more (less) or choose a higher (lower) calorie option to maximize utility.

Our model (shown in the supplementary materials) predicts that it is the gap in the actual calorie content and the reference point expectation that has the potential to influence food choices. We do not directly elicit the reference point from participants to avoid experimenter demand effects for reactions to calorie information. Instead, we exogenously manipulate the gap in actual calories and the reference point by carefully controlling the appearance of the meals to seem identical in the number of calories despite having large differences in a controlled framed field experiment in partnership with a national restaurant chain. More specifically, we created four customized meals that looked nearly identical but substantially differed in the number of calories: (1) a 300-calorie wrap, (2) a 600-calorie wrap, (3) a 900-calorie wrap, and (4) a 600-calorie reference sandwich.

In Stage 1, we elicited participants’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) for each of the four customized meals using an incentivized Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) auction mechanism10. No calorie information was provided during this stage. Participants were presented with a picture of each meal separately, along with a description of its ingredients, and were asked to report their maximum WTP for the meal using a $10 budget. The objective of soliciting meal valuations under no information was to use these valuations to construct binary menus in Stage 2 with equalized value by adding a monetary allocation to the lesser valued option. While previous literature has documented deviations from theoretical predictions of the BDM mechanism11,12,13, any deviations in the mechanism in our context are less of a concern since they would be constant for all products and we only use the valuations to construct binary menus in Stage 2 and not as an externally valid measure of willingness-to-pay. Three binary menus were presented in Stage 2, all containing the 600-calorie sandwich as reference and one of the three wraps. Homegrown (prior) preferences for food affect meal selections and produce noise in the responses since some people may naturally prefer the sandwich (or wraps) regardless of any information provision. To account for homegrown preferences, a monetary allocation equal to the difference in valuations between the two meals was supplemented to the lesser valued meal in each binary menu. That is, we equalized the value of each alternative at the individual level to induce indifference between the two alternatives in the menu without providing any additional information. For example, if a participant valued Meal 1 at $5 and Meal 2 at $3 in Stage 1, then in Stage 2 the participant was presented with a binary menu consisting of {Meal 1} or {Meal 2 plus a $2 monetary allocation}. Because the value of the two alternatives is equalized with a monetary allocation, we expect equal (50% choice) frequency for each meal when no calorie information is provided. Crucially, this exact point prediction is empirically testable, and the design isolates the effect of the calorie information treatment incorporated in Stage 2 as the sole driver of any departures from equal choice frequency in the control condition.

Stage 2 was implemented as a between-subject design, where participants were randomly assigned to either the no-information control or the calorie information treatment. Participants in the treatment received calorie information for each meal in three binary menus. Menu 1: a 600-calorie sandwich or a 600-calorie wrap, Menu 2: a 600-calorie sandwich or a 900-calorie wrap, and Menu 3: a 600-calorie sandwich or a 300-calorie wrap. By design, any departures from the equal proportion of meal choices expected in the control and the treatment can only be attributed to the additional calorie information. Each of the three binary menus was constructed to test the boundary conditions that result in a change in meal choices via affecting the distance in the number of calories of the two meals through the manipulation of consumer expectations with nearly identically perceived meals with respect to calories in the control.

Menu 1 (Prediction 1) is a binary menu with the 600-calorie sandwich and the 600-calorie wrap (plus any compensation) provides information that carries no instrumental value as the calorie distance between the two meals is zero and the gap between the unobserved reference point remains constant for these two options. Note that the reference point is unobserved, but the design allows to make inferences regarding the gap in expectations via manipulation of the meals. Stated differently, compared to the equal choice frequency in the control, providing calorie information in Menu 1 does not change the relative attractiveness (the distance between any meal and the unobserved reference point) compared to the control, and our model predicts no change in the frequency of choice for the sandwich (50% frequency of choice).

Menu 2 (Prediction 2) consists of the 900-calorie wrap and the 600-calorie sandwich (plus any compensation). The model predicts that when calorie information reveals that one of the meal’s calories is higher and hence more likely to be above the reference point (900-calorie wrap), it would make the other alternative (600-calorie sandwich) more attractive and more likely to be chosen. Intuitively, the model predicts that if one of the two meals is more likely to be above the reference point, participants are more likely to choose the lower-calorie option.

Menu 3 (Prediction 3) presents the 300-calorie wrap and the 600-calorie sandwich (plus any compensation). The model predicts that when calorie information reveals that one of the meal’s calories is lower and hence more likely to be below the reference point (300-calorie wrap), it would make the other alternative (600-calorie sandwich) more attractive and more likely to be chosen. Intuitively, the model predicts that if one of the two meals is more likely to be below the reference point, participants are more likely to choose the higher-calorie option.

We purposely avoided asking participants about their calorie beliefs or their reference point prior to any food selections to reduce experimenter demand effects and anchoring around their reference point. We elicited beliefs about the number of calories for each meal at the end of the experiment to verify that subjects indeed believed the meals had the same number of calories. As such there is no Bayesian update since the reference point in our design is unobserved and the exogenous variation seeks to exogenously vary the perception of the calorie distance between two meals. The manipulation was successful, and participants reported similar calorie expectations across the meals despite the actual large calorie differences. Although the true calorie difference between the wraps ranged from 300 to 600 calories, the average calorie beliefs elicited ex-post for non-informed participants were all within 45 calories of each other, confirming a successful exogenous manipulation of calorie information.

Our study provides a relevant contribution to the discussion of calorie information by suggesting that the numeric value of the calorie information alone is not sufficient to explain the impact that information has on food choice, but it is the gap between the (unobserved) calorie reference point expectation and actual realization that reveals the instrumental value of the information and its likelihood of affecting food choice outcomes. Our design manipulates the calorie distance between two meals using meals perceived to be identical in the number of calories without asking for or observing the reference point. This is crucial to avoid experimenter demand effects and anchoring where participants might adjust their behavior towards socially desirable outcomes if they were asked to report their beliefs about calories. Our results suggest that providing calorie information alone may not necessarily lead to the intended behavioral change of information-based policies. Calorie information interventions are more likely to affect behavior if they affect the gap in reference expectations and actual calories. Since in the field, actual calories are fixed for a meal, the gap can be affected by directly influencing the reference point threshold perhaps in a more individualized way. This can be accomplished by providing customized meal-specific calorie recommendations based on individual characteristics such as height, weight, gender, age, and the level of physical activity as a way to directly influence the reference point expectation-realization gap to make interventions more salient than the current generic daily calorie consumption guidelines that make it more difficult for people to track and comply.

Results

Constructing equally attractive meals and controlling for homegrown preferences

Result 1: In the Control without calorie information, subjects choose the sandwich with equal frequency as the wrap in all three binary menus.

Result 1 confirms a successful manipulation of the meals being perceived and valued equally, and a successful design controlling for homegrown preferences. In the control under no information, participants select the sandwich and the wrap with equal frequency in all three binary menus. Intuitively, since differences in the value between the sandwich and the wraps are compensated with a monetary allocation to equalize their value, participants should be indifferent between the two options when calorie information is absent. The red (darker) bars on Fig. 1 show the proportion of subjects in the control choosing the 600-calorie sandwich over each of the three wraps in Stage 2, with the dotted line representing the 50% model prediction. The proportion of sandwich choices are not statistically different than 50% for each of the three binary menus. On average, 57% of subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 300-calorie wrap (p-value = 0.264), 55% of subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 600-calorie wrap (p-value = 0.385), and 51% of subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 900-calorie wrap (p-value = 0.901, for a z-proportion test). Jointly, these proportions are not significantly different from 50% (p = 0.57, for a joint chi-squared proportion test). In addition, results from pairwise comparisons using z-tests show no significant differences in the proportion of choices across the three wrap options (p = 0.37 for 300-calorie vs. 600-calorie wraps; p = 0.53 for 300-calorie vs. 900-calorie wraps; p = 0.68 for 600-calorie vs. 900-calorie wraps). These results persist when controlling for observables in an OLS regression. The OLS regression estimates clustered at the individual level are presented in SI Table S1.

Effect of calorie information on meal selection

Result 2: Subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich, and the 600-calorie wrap at the same frequency with calorie information in Menu 1.

The frequency of choices for the 600-calorie sandwich and the 600-calorie wrap is the same in the control (50%) and the calorie information condition as predicted by the model. Even though the reference point is unobserved, since the calorie information is 600 calories for each item, the gap between the unobserved reference point and the 600-calorie realization for each meal is identical. We find that 54% of subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 600-calorie wrap in the calorie information condition; this value is not statistically different than 50% (p = 0.53) or the corresponding proportion in the control (p = 0.86). Table 1 presents the estimates of a logit regression with the choice of the sandwich as the dependent variable and confirms the insignificant effect in Menu 1. The standard errors are clustered at the individual level to account for the three menu choices made by each subject. Stated differently, since both alternatives have an identical number of calories, the introduction of calorie information does not change the relative attractiveness of any alternative.

Result 3: Subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich more frequently than the 900-calorie wrap with calorie information in Menu 2.

We find that 68% of subjects in the calorie information condition choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 900-calorie wrap, which is statistically different than 50% (two-sided z-approximation test, p < 0.01) and statistically higher than the proportion of sandwich choices in the control (p = 0.0496). When adjusting for multiple hypothesis testing (Bonferroni), the comparison against 50% remains statistically significant (p = 0.01). This is not the case when comparing against the control (p = 0.15). In contrast, logit regression models with clustered standard errors at the individual level and controls indicate statistically significant differences in choice proportion between 600-calorie sandwich (with calorie information) and control(p = 0.02). Table 1 confirms this result with the information and 900-calorie wrap interaction coefficient is positive and statistically significant (p = 0.02 without controls; p = 0.022 with controls), indicating that subjects chose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 900-calorie wrap more frequently when provided with calorie information. This result aligns with our model predictions and provides a potential explanation for evidence suggesting a reduction in food intake as a result of calorie information provision3,14,15.

Result 4: Subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich, and the 300-calorie wrap at the same frequency with calorie information in Menu 3.

Around 58% of subjects in the calorie information condition choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 300-calorie wrap. While the proportion of choices for the sandwich goes in the predicted direction of higher-calorie choice, the result is not statistically different from 50% (p = 0.17) nor the corresponding choices made in the control (p = 0.86). Bonferroni corrections yield the same conclusions for result 3. The Table 1 regression also confirms this result with the information and 300-calorie wrap interaction coefficient is not statistically significant (p = 0.6942 without controls; p = 0.6975 with controls), indicating that the frequency at which subjects choose the 600-calorie sandwich over the 300-calorie wrap was not influenced by observing calorie information. This result aligns with previous evidence of null effects of information provision on food and beverage choices reported in3,16,17,18,19,20.

Menu 3 was designed to test the boundary condition when calorie information may produce an increase in calorie consumption. For instance, when individuals might feel more justified in choosing a higher-calorie option like the 600-calorie sandwich, assuming they have more room in their calorie budget. Participants did not gravitate towards a higher calorie alternative perhaps because they may have perceived the lower 300-calorie alternative to surpass a minimum reference point threshold and still be fulfilling according to the number of calories. This indicates that a much larger difference in the expectation-realization calorie gap would be needed to produce the effect reported by9. However, it is not feasible in our current design to create a meal with less than 300 calories without significantly affecting the ingredients and the appearance of the lower-calorie wrap. Nevertheless, this result points to a potential deficit in subjects substantial and pervasive underestimation of calories in our data and as abundantly documented in previous literature which may require much lower levels (than 300 calories) to produce an effect.

Discussion

We develop a simple model (in the supplementary materials) based on an unobserved reference point expectation and manipulated directly the gap with the information realization framework to rationalize the contradictory evidence on the effectiveness of information-based policies at reducing calorie intake. The results of our controlled experiment show that the numeric value of the calorie information alone is not sufficient to predict the impact that information has on food choice, but it is the gap in information and realization that reveals the likelihood and direction of its effect on food choice outcomes.

The need for nutritional information to support consumer food choices and reduce calorie intake is generally agreed on by all stakeholders and is reflected worldwide in market practice and behavioral-based policies. Nearly all Western countries have regulations for nutritional information requirements for food, with mandatory labeling in the European Union since 2016 [Source: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/labelling-and-nutrition/food-information-consumers-legislation_en] and the United States since 2018. Despite these efforts, the provision of nutritional information has a mixed record regarding its influence on actual food choice21,22. For instance, recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the topic have only found average effect sizes of information nudges on healthy eating ranging from null or weak23 to moderate24. For example, based on results from a meta-analysis published in 39 review papers (with 1104 studies reported for all reviews)21, concludes that with few exceptions (e.g.,25,26), there appears to be a consensus that the mere provision of caloric information is unlikely to have strong effects on food choices, or results are inconclusive8. These literature reviews evaluate thousands of studies reporting large discrepancies in the results, which indicates that the literature is far from reaching an agreement. On this front, the results of our controlled experiment indicate that the interaction between the actual calorie content of the meal and consumers’ reference calorie intake is more likely to be driver of food choice and consumption. This approach sharply contrasts with the thousands of studies that only examine the effect of providing the calorie content of the meal while ignoring consumers’ reference points. Some notable exceptions include17,27, and28.

Our experiment is limited by its inability to directly elicit individual reference points or expectations regarding caloric intake. Such elicitation is challenging due to the general absence of experience or expert guidance on meal-specific calorie benchmarks. Future research could explore the manipulation of calorie reference points using straightforward experimental designs. Subsequent studies may focus on strategies to directly influence individual reference points, potentially beginning with the division of daily caloric recommendations into meal-specific guidelines to enhance the salience of these reference points. This will also make it easier for individuals to keep track of calorie intake per meal compared to daily calorie intake. More importantly, customized calorie recommendations per meal need to be adjusted by biological factors such as age, weight, height, gender, and physical activity level, may serve to directly influence the calorie reference point expectations of consumers. This approach holds promise, particularly given the scarcity of existing literature on reference points within food consumption contexts. A second limitation of our experiment is that it does not track the dynamics of information over a prolonged period to track other relevant outcomes including weight loss and other health benefits. Further work is needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying habit formation and behavioral changes over time, as well as the possibility of expectation manipulations in the field as an intervention venue.

Materials and methods

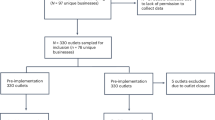

We conducted a controlled framed field experiment in the Fall of 2022 with a sample of 130 consumers recruited through bulk emails within an existing database and ads posted in the local newspaper. The sample was restricted to individuals without dietary restrictions or food allergies. Subjects were instructed to refrain from eating three hours prior to the experiment to ensure a similar state of hunger across subjects and they were informed there would be a possibility of eating a meal during the study. They received $25 of compensation plus any additional earnings in cash and/or food as described in the procedures below. The total average compensation was $30.42 and 78% of participants received a meal as part of their compensation. The study was pre-registered at the AEA RCT Registry (RCT-ID AEARCTR-0009838).

Human ethics

Subjects were 18 or older and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All the experimental protocols were approved by the Texas A&M Institutional Review Board IRB2022-0524D. All methods were carried out in accordance with the human ethics guidelines and regulations of this IRB protocol.

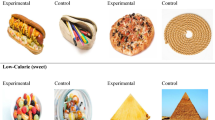

Meal customization

Four meals with the same ingredients were customized to look as identical as possible while substantially differing in their calorie content. We partnered with a national restaurant chain and worked with one of their nutrition experts to create four meals representative of items usually available on their menu: a 600-calorie sandwich, a 300-calorie wrap, a 600-calorie wrap, and a 900-calorie wrap. The meal pictures displayed on the menus were captured by a professional photographer under identical lighting conditions and camera angles to ensure a similar appearance (see SI Fig. S1 for visual menus). Subjects participated in seven tasks divided into Stage 1 (4 tasks) and Stage 2 (3 tasks). At the end of the experiment, only one of the seven tasks was randomly chosen for implementation, and subjects were compensated with additional payment and/or a meal based on their decisions as described below.

Stage 1: willingness-to-pay

We first elicited individuals’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) for each of the four customized meals using an incentivized BDM auction mechanism10. No calorie information was provided in Stage 1 (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Subjects completed four tasks in this stage, one for each meal (1 sandwich and 3 wraps). In each task, subjects viewed a picture of the meal and a description of its ingredients, and were asked to report their maximum willingness-to-pay for the meal using a budget al.location of $10. Across subjects, the order of the four tasks was randomized to account for ordering effects and the labels of the wraps were randomized to account for framing effects. Prior to completing the four tasks, subjects were given detailed instructions of the procedures including two examples with coffee mugs to illustrate how the BDM mechanism works. In order to proceed, participants had to correctly answer two comprehension questions on the market valuation mechanism. No practice rounds were included in the study. If one of the four tasks from Stage 1 was selected for implementation, a market price between $0 and $10 was randomly generated by the computer. If the bid for the meal was higher or equal to the market price, the subject was required to purchase and eat the meal and pay the market price out of the $10 budget, else the subject didn’t purchase the meal and kept the $10. Any remaining funds were added to the subject’s final payment. The market realization for the binding round did not occur until the end of the experiment to avoid any strategic bidding and income effects.

Stage 2: menu selection

In Stage 2, subjects were randomly assigned to one of two between-subject conditions: (1) calorie information condition (N = 65), and (2) no-information condition or control (N = 65). Subjects were presented with three binary menus (i.e., three tasks). In each menu, they were asked to choose between two options consisting of a meal and a monetary allocation. There is no budget for Stage 2, and the incentive is the choice of an item for each binary menu. The binary meal menus were as follows: Menu 1: the 600-calorie sandwich or the 600-calorie wrap, Menu 2: the 600-calorie sandwich or the 900-calorie wrap, and Menu 3: the 600-calorie sandwich or the 300-calorie wrap. The order of the three tasks was randomized to minimize ordering effects. Since each binary menu had two items of equal value with the individual level monetary compensation to the lesser valued alternative, we induce approximate indifference between the two meals without providing any information. A representation of a menu is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3.

Subjects assigned to the information condition received calorie information for each meal on the three binary menus, while subjects in the control received no calorie information. The menu selection task was also incentivized. If one of the three binary menus tasks was selected for implementation, the subject received the chosen meal plus any monetary allocation (if any). Since only one of the seven tasks (from Stage 1 and Stage 2) is randomly selected for payment, participants can only receive one meal at most to avoid any potential satiation or incentive distortion for calories.

After completing Stage 2, subjects filled out a survey regarding their socio-demographic characteristics, including the beliefs about the calorie content of each of the four meals to verify the success of our manipulation. Calorie beliefs at the end of the experiment were incentivized with $1 for responses that were within 25 calories of the actual amount. For the control, participants provided beliefs without ever accessing calorie information, providing a good measure of their natural beliefs. Participants in the treatment provided their calorie beliefs without the information to assess if they were able to correctly provide the calorie content after being exposed to information. The average compensation was $30.42 and 78% of subjects received a meal. If the selected task included a meal, subjects received the meal, bottled water, and a napkin. There were no restrictions on the time or the quantity of the meal to be consumed, but subjects could not take any food home. The binding meal was weighed using a food scale before and after the session to calculate the amount of food consumed. The experimental instructions and survey questions are provided in SI Appendix, Survey S1.

Manipulation check for the gap between calorie realization and the unobserved reference point

The individual reference point presented in the theoretical model in the supplementary materials is unobserved and not explicitly elicited. Our manipulation to make the meals appear to have the same number of calories while substantially differing in their actual values serves as a proxy measure to empirically test the distance between the unobserved and fixed reference point and the realized calories. Intuitively, if the reference point is fixed and participants also perceive all the meals to have the same number of calories, then the gap in the control condition is constant for each one of the three menus. This is the intuition that provides empirical support for equal frequency choice in the control. However, in the calorie information treatment, the realized number of calories for each meal differs for each one of the three menus while the reference point is fixed. This feature in our design allows us to test a proxy for the gap in the reference point and realized calories to each menu in the treatment while keeping it fixed in the control.

We deliberately refrained from eliciting individual reference points for calorie intake—or any related information—to prevent experimenter demand effects (participants realizing the study is about calories) and anchoring participants’ preferences to a specific reference prior to their engagement with the subsequent tasks. Prior research indicates that anchoring effects are particularly salient in contexts comparable to ours: when participants interact directly with an experimenter (i.e., heightened observability); when they are familiar with and regularly consume the good under evaluation (e.g., food); and when the anchor is perceived as informative (e.g., calorie expectations may be interpreted as recommended intake)29,30,31. Moreover, estimating calorie reference points is challenging due to individual variability in daily energy requirements. This difficulty is particularly pronounced for lunch, as most individuals lack experience or expert guidance regarding appropriate caloric intake for individual meals.

Participants provided their beliefs at the end of the experiment to avoid experimenter demand effects and only to confirm the manipulation for perceiving the meals to have the same number of calories. In the control, participants provided beliefs without ever accessing calorie information, providing a good measure of their homegrown beliefs. In the treatment, participants provided their calorie beliefs after exposure to the meals with calories, but without the information to assess if they were able to correctly provide the calorie content after being exposed to information. Overall, consistent with previous literature4, uninformed participants underestimate the calories in the meals with an average of 438 calories. This expected average calorie level is lower than the actual 600 calorie average across the four meals. In the control, the average calorie beliefs for the 600-calorie sandwich, 300-calorie wrap, 600-calorie wrap, and 900-calorie wrap are 493 calories, 399 calories, 414 calories, and 444 calories, respectively. Although the true calorie difference among the 300-, 600-, and 900-calorie wraps ranged from 300 to 600, the average calorie beliefs for uninformed participants were all within 45 calories of each other, confirming a successful manipulation and more importantly showing that the gap between the unobserved reference point and the calorie beliefs is constant across the three meals at the aggregate level. Mann-Whitney pairwise comparisons for beliefs in the control between the 600-calorie sandwich and the three wraps reveal that there is a statistical difference between the calorie beliefs of the 600-calorie sandwich and the 300-calorie wrap (p < 0.001), the 600-calorie wrap (p < 0.001), and the 900-calorie wrap (p = 0.07). Despite these statistically significant differences, the magnitudes of the differences are relatively small when compared to the actual caloric difference, suggesting a successful calorie-expectation manipulation.

The average calorie beliefs in the calorie information condition for the 600-calorie sandwich, 300-calorie wrap, 600-calorie wrap, and 900-calorie wrap are 597 calories, 468 calories, 538 calories, and 590 calories, respectively. The calorie beliefs were higher than those in the control, and closer to the actual 600 calorie average. Note that the average calorie belief for the sandwich was 597 calories, indicating that participants were paying attention to the information provided and provided accurate number of calories for the sandwich since it is the only distinct meal from the wraps. However, without information, they still had difficulties differentiating the calorie content of the wraps, further providing confidence in the effectiveness of the calorie manipulation that the realized calorie information was only effective when the wrap calorie was displayed in the menus and participants were still unable to distinguish the actual calorie content for the wraps unless they saw it at the decision time.

Data availability

De-identified data collected for the study and presented in this manuscript, including individual participant data and a data dictionary, will be made available to others upon reasonable request upon publication of this article, provided approval by regulatory authorities. Data can be requested by sending an e-mail to the corresponding author.

References

Zlatevska, N., Barton, B., Dubelaar, C. & Hohberger, J. Navigating through nutrition labeling effects: a second-order Meta-analysis. J. Public. Policy Mark. 43 (1), 76–94 (2024).

Balfour, D., Moody, R., Wise, A. & Brown, K. Food choice in response to computer-generated nutrition information provided about meal selections in workplace restaurants. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietetics. 9 (3), 231–237 (1996).

Bollinger, B., Leslie, P. & Sorensen, A. Calorie posting in chain restaurants. Am. Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 3 (1), 91–128 (2011).

Burton, S., Bates, K. W. & Huggins, K. A. To eat or not to eat: Effects of objective nutrition information on consumer perceptions of fast food chain’s meal healthiness, future health concerns, and meal repurchase intentions. Market. Theory Applic. 87. (2006).

Yamamoto, J. A., Yamamoto, J. B., Yamamoto, B. E. & Yamamoto, L. G. Adolescent fast food and restaurant ordering behavior with and without calorie and fat content menu information. J. Adolesc. Health. 37 (5), 397–402 (2005).

Hammond, D., Goodman, S., Hanning, R. & Daniel, S. A randomized trial of calorie labeling on menus. Prev. Med. 57 (6), 860–866 (2013).

Kiszko, K. M., Martinez, O. D., Abrams, C. & Elbel, B. The influence of calorie labeling on food orders and consumption: a review of the literature. J. Community Health. 39, 1248–1269 (2014).

Bleich, S. N., Economos, C. D., Spiker, M. L., Vercammen, K. A., VanEpps, E. M., Block,J. P., Roberto, C. A. A systematic review of calorie labeling and modified calorie labeling interventions: impact on consumer and restaurant behavior. Obesity 25 (12), 2018–2044. (2017).

Dumanovsky, T. et al. Changes in energy content of lunchtime purchases from fast food restaurants after introduction of calorie labelling: cross sectional customer surveys. bmj, 343. (2011).

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M. H. & Marschak, J. Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behav. Sci. 9 (3), 226–232 (1964).

Cason, T. N. & Plott, C. R. Misconceptions and game form recognition: challenges to theories of revealed preference and framing. J. Polit. Econ. 122 (6), 1235–1270 (2014).

Canavari, M., Drichoutis, A. C., Lusk, J. L. & Nayga, R. M. Jr How to run an experimental auction: A review of recent advances. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 46 (5), 862–922 (2019).

Caputo, V., Lagoudakis, A., Shupp, R. & Bazzani, C. Comparing experimental auctions and real choice experiments in food choice: a homegrown and induced value analysis. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 50 (5), 1796–1823 (2023).

Barahona, N., Otero, C. & Otero, S. Equilibrium effects of food labeling policies. Econometrica 91 (3), 839–868 (2023).

Zhu, C., Lopez, R. A. & Liu, X. Information cost and consumer choices of healthy foods. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 98 (1), 41–53 (2016).

Lim, S. L., Penrod, M. T., Ha, O. R., Bruce, J. M. & Bruce, A. S. Calorie labeling promotes dietary self-control by shifting the Temporal dynamics of health-and taste-attribute integration in overweight individuals. Psychol. Sci. 29 (3), 447–462 (2018).

Downs, J. S., Wisdom, J., Wansink, B. & Loewenstein, G. Supplementing menu labeling with calorie recommendations to test for facilitation effects. Am. J. Public Health. 103 (9), 1604–1609 (2013).

Ellison, B., Lusk, J. L. & Davis, D. The impact of restaurant calorie labels on food choice: results from a field experiment. Econ. Inq. 52 (2), 666–681 (2014).

Fernandes, A. C. et al. Influence of menu labeling on food choices in real-life settings: a systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 74 (8), 534–548 (2016).

Melo, G., Zhen, C. & Colson, G. Does point-of-sale nutrition information improve the nutritional quality of food choices? Econ. Hum. Biology. 35, 133–143 (2019).

Bauer, J. M. & Reisch, L. A. Behavioural insights and (un) healthy dietary choices: A review of current evidence. J. Consum. Policy. 42, 3–45 (2019).

Cadario, R. & Chandon, P. Which healthy eating nudges work best? A meta-analysis of field experiments. Mark. Sci. 39 (3), 465–486 (2020).

Long, M. W., Tobias, D. K., Cradock, A. L., Batchelder, H. & Gortmaker, S. L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of restaurant menu calorie labeling. Am. J. Public Health. 105 (5), e11–e24 (2015).

Arno, A. & Thomas, S. The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC public. Health. 16, 1–11 (2016).

Campos, S., Doxey, J. & Hammond, D. Nutrition labels on pre-packaged foods: a systematic review. Public Health. Nutr. 14 (8), 1496–1506 (2011).

Littlewood, J. A., Lourenço, S., Iversen, C. L. & Hansen, G. L. Menu labelling is effective in reducing energy ordered and consumed: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent studies. Public Health. Nutr. 19 (12), 2106–2121 (2016).

Downs, J. S., Loewenstein, G. & Wisdom, J. Strategies for promoting healthier food choices. Am. Econ. Rev. 99 (2), 159–164 (2009).

Chung, D. H., Han, D. B., Nayga, R. M. Jr & Lee, S. H. Does more information mean better choices? A study on calorie display and consumer behavior in restaurants. Food Qual. Prefer. 113, 105044 (2024).

Ariely, D., Loewenstein, G. & Prelec, D. Arbitrarily coherent preferences. In The Psychology of Economic Decision. (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Exley, C. L., Judd, B. & Kessler Motivated errors. Am. Econ. Rev. 114 (4), 961–987 (2024).

Ioannidis, K. & Offerman, T. and Randolph Sloof. On the effect of anchoring on valuations when the anchor is transparently uninformative. J. Econ. Sci. Assoc. 6 (1), 77–94. (2020).

Acknowledgements

We received useful comments from Valon Vitaku, Changkuk Im, Dustin Tracy, Samir Huseynov, and participants at the 2023 ESA North America and 2024 FDRS conferences. This study was pre-registered as AEARCTR-0009838.

Funding

We received funding support from the Institute for Advancing Health through Agriculture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP, BT, MS, GM designed the experiment, conducted the analysis, wrote and reviewed the manuscript. BT collected data and cleaned and processed the raw data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toney, B.A., Palma, M.A., Segovia, M.S. et al. Why does calorie information produce mixed evidence for its effect on food choices?. Sci Rep 15, 42413 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26687-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26687-6