Abstract

Designed ecology aims to proactively create sustainable ecosystems, yet quantifying the ecological effects of design parameters remains challenging due to the complexity of mathematical models and the high cost of long-term field observations. This study presents a scaled physical model system simulating nonpoint source pollution processes in sloping landscapes, enabling rapid and controlled analysis of key design parameters in designed ecology. The results indicate that (1) through 24 laboratory experiments (slope length 0.25–1 m), runoff pollutant concentrations consistently follow a power-law decay over time, with 17 groups achieving a goodness-of-fit above 0.90. (2) Orthogonal analysis identified slope material and soil thickness as the most influential factors, while slope length and width had limited effects. (3) Field validation in navel orange orchards (slope length 4–16 m) in the Three Gorges Reservoir area demonstrated that the physical model reliably reproduced the trends of runoff and pollutant loss observed in real slopes. These findings demonstrate that scaled physical models can effectively bridge laboratory and field studies, providing actionable guidance for parameter selection in landscape design, and supporting the implementation of nature-based solutions for water ecosystem restoration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Designed ecology is an emerging paradigm that emphasizes the proactive creation and management of ecosystems to achieve specific ecological and societal goals, such as enhancing ecosystem services, maintaining biodiversity, increasing system resilience, and supporting nature-based solutions1,2, rather than merely restoring natural states3. This approach is increasingly important as global and local ecosystems face unprecedented disturbances from human activities4,5. To design a sustainable and resilient ecosystem6, understanding and quantifying the effects of design parameters—such as landform configuration, soil properties, and hydrological connectivity—on ecosystem functions in regionally specific contexts is essential for developing actionable ecological knowledge and supporting nature-based solutions7.

Among various ecological challenges, agricultural nonpoint source pollution (ANSP) in sloping landscapes stands out as a critical issue due to its high sensitivity to design parameters8,9. Sloping agricultural lands are major sources of nonpoint pollution, especially for nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus10. These pollutants are transported to surface waters mainly through rainfall-driven processes such as raindrop impact, runoff, and soil erosion11,12. Characteristics of slope surfaces like slope length9,13,14, gradient15, rainfall intensity16,17, vegetation cover18, and soil disturbance19 directly shape pollutant migration. In particular, slope length is pivotal, as it influences both runoff generation and the transport of sediment-bound and dissolved pollutants.

However, quantifying the effects of design parameters such as slope length, soil thickness, and slope material on ANSP remains difficult due to the limitations of traditional field monitoring and mathematical modelling approaches. Field observations have long been used in ecological studies to evaluate system performance based on key parameters related to scale, morphology, water, soil, and vegetation20,21, but are often limited by high costs, long durations, and difficulties in isolating the effects of individual parameters, and may not always deliver timely and targeted insights needed for practical design decisions. Alternatively, mathematical models are often employed to simulate processes such as rainfall-runoff, sediment transport, and pollutant migration in ANSP research15,22, but real-world complexity and the need for simplification often limit their applicability. This includes simplification or omission of physical processes, difficulty in obtaining site-specific parameter data, challenges in representing interactions across scales, and limitations in coupling multiple system components18,23,24. To address this gap, downscaling through physical modelling offers a promising approach: it enables controlled experiments that systematically evaluate how design parameters influence pollutant transport, thereby generating actionable knowledge for ecological design and management.

Specifically, downscaling enables shorter study durations, better control of experimental conditions, and more clearer causal analysis25, which offers a powerful way to simulate and explore complex processes and feedbacks26. While physical models originated in the hydraulic engineering27,28,29,30, they have since been used to simulate pollutant diffusion in estuaries31, constructed wetlands32, and hydrological and pollutant migration processes on slopes10. As laboratory analogs of real ecosystems, physical models offer advantages over field observations, but may introduce distortions due to scale effects33,34. Some loosely scaled models, however, can still capture essential system characteristics, such as those laboratory-created small-scale rivers and deltas (typically from tens of centimeters up to several meters in length)29,30,35. Building on this approach, this work uses scaled physical models to investigate rainfall-runoff generation, soil erosion, and nutrient transport under varying design parameters on sloping agricultural land. This leads to three key questions:

(1) Can scaled physical models balance experimental convenience with reliable simulation of runoff generation and nonpoint source pollutant transport on sloping agricultural land?

(2) Which processes (e.g., runoff dynamics, pollutant concentration decay) can be accurately reproduced under controlled conditions?

(3) Which design parameters (slope length, soil thickness, slope material, width) most critically affect simulation outcomes?

In this study, we construct a scaled physical model system to simulate rainfall, slope, soil, and solute transport processes on slopes, with a particular focus on the effects of slope length, soil thickness, material and width. By employing an orthogonal experimental design, we systematically evaluate the sensitivity of ANSP to these parameters under controlled rainfall conditions, generating insights directly relevant to designed ecological interventions. The experimental results from the physical modelling system were benchmarked against field monitoring data for citrus cultivation-induced ANSP in the Three Gorges Reservoir area, China. By bridging laboratory experiments and field observations, our approach advances the quantitative foundation of designed ecology. The results provide a scientific basis for parameter selection and optimization in the design of sustainable sloping landscapes, supporting the implementation of nature-based solutions and the restoration of water ecosystems in both urban and rural contexts.

Model design and experimental methods

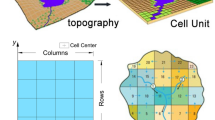

Slope physical model

Model design

The transport of soil solutes by runoff during rainfall is a fundamental process driving ANSP on slopes8. To replicate this under controlled laboratory conditions, we developed a slope physical model system. This system comprises five core components: (1) a soil tank with adjustable slope length and width; (2) slope materials with contrasting soil textures and variable thicknesses to represent solute transport media; (3) a solute tracer (NaCl); (4) an artificial rainfall apparatus; and (5) runoff collection and measurement devices (Fig. 1).

Physical model experimental setup. Schematic diagram created by the authors using SketchUp 2021 (https://www.sketchup.com); all photos were taken by the authors.

(1) Soil tank.

The stainless steel soil tank has an adjustable length (0.25–1 m) and an open outlet for runoff collection. It is filled with either homogenized river sand or agricultural sandy loam soil (see Sect. 2.2). Baffles at both ends confine the soil, with a lower opening for runoff outflow. The tank bottom is impermeable to prevent leakage.

(2) Slope material.

Two materials were used in the experiments, selected based on different experimental objectives. Agricultural sandy loam soil was used to represent the characteristic soil type of the field observation site. This soil was collected from the top 0.05–0.15 m layer of cultivated land, then air-dried, sieved to remove coarse fragments, and crushed before packing.

In parallel, homogenized river sand was employed as a simplified and readily available substrate, which is commonly used in physical modelling due to its uniform particle size and stable infiltration properties25. The river sand used in this study had an average particle size of 0.125–0.25 mm.

(3) Solute tracer.

Sodium chloride (NaCl) and other salts have been widely used as tracers to simulate solute transport in the soil, as their concentrations can be measured via electrical conductivity. In this study, NaCl was not used to simulate specific reactive pollutants such as phosphorus or organic nitrogen compounds, but rather served as a conservative tracer to indicate the migration trend of solutes with water flow. Similar approaches using NaCl and other water-soluble salts like KBr are commonly applied in laboratory-scale soil transport studies36,37. Given its high solubility and stability, NaCl also provides a potential proxy for exploring the behaviour of highly soluble pollutants such as nitrate-nitrogen in future experiments.

Specifically, air-dried and sieved soil was mixed with an appropriate amount of this tracer via an electronic balance device. After careful comparison through preliminary experiments, the optimal ratio was 1 g per soil unit (0.25 m length × 0.20 m width × 0.05 m thickness).

(4) Rainfall apparatus.

The rainfall apparatus delivered a constant intensity of 1.20 mm/min, matching the conditions used in the field experiments. The artificial rainfall system comprised suction heads, a water pump (Mius Mist B50), and multiple spray nozzles. Each spray nozzle operated at a pressure of 4–8 bar, with a pressure regulator ensuring consistent water pressure and keeping the flow rate at 60 mL/min, evenly distributed over a 0.25 m × 0.20 m area. To ensure comparability across trials, the rainfall intensity was kept constant. The duration for each rainfall event was approximately 30 min, continuing until the runoff solute concentration reached a stable value.

(5) Collection and measurement.

Runoff was collected at the tank outlet and measured first before sampling for conductivity testing. Conventional flowmeters were unsuitable because of the low flow rate and drip-like nature of runoff in this physical model. Instead, a HOBO RG3-M tipping bucket rain gauge from Onset Corporation (USA) was employed, with each tipping bucket representing 0.2 mm and a minimum sampling interval of 1 s. Data recorded by the accompanying HOBOware software were stored on a computer and converted into cumulative minute-by-minute flow rates for analysis.

Water samples were manually collected from the rain gauge outlet via beakers. The conductivity was measured with a DDS-11 A conductivity meter manufactured by Shanghai Yueping. The electrode constant of the meter was 1.1, with a measurement range of 0.00 µS/cm to 199.9 mS/cm and a full-scale error of ± 2%. The measured conductivity range for this experiment was 100 µS/cm to 10 mS/cm, with an instrument error within 1 µS/cm, meeting the relevant accuracy requirements. As the electrode was sensitive to temperature, the water conductivity and temperature were recorded before the experiment, and manual temperature compensation was applied. Standard solutions were used to calibrate the instrument before each experiment. After each session, the electrodes were cleaned, dried, and stored.

Data collection and result validation

(1) Sample collection.

Based on preliminary tests, runoff samples were collected in three stages: every 30 s for the first 2 min (yielding 5 samples), then at 1-minute intervals for the next 8 samples, and finally at 2-minutes intervals for the last 10 samples. This resulted in a total of 23 samples per experiment. For data consistency in subsequent analyses, the first sample was recorded as being collected at the first minute after runoff began. Each sample volume was 80 mL, and timing was paused during collection.

(2) Data preprocessing.

The relationship between NaCl concentration and electrical conductivity (EC) was calibrated in the lab, yielding a strong linear regression38. Calibration was conducted under controlled temperature conditions using 10 standard NaCl solutions, with EC values ranging from 100 µS/cm to 10 mS/cm, covering most of the conductivity range observed in the experiment. NaCl was precisely weighed using an electronic balance and dissolved in water to measure the electrical conductivity. The resulting equation was used to convert conductivity readings to NaCl concentrations for all samples:

where ρ is the NaCl mass concentration (mg/L), k is the electrical conductivity (µs/cm), and R2 = 0.9996. The calibration data and the regression plot are provided in the Supplementary Information (Table S1, Fig. S1).

(3) Result validation.

Extensive field and laboratory experiments have established that temporal variations in runoff pollutant concentrations typically exhibit either exponential or power-law decay patterns39. Multiple studies have specifically confirmed that solute concentrations in slope runoffs consistently demonstrate power-law relationships11,15,40.

To validate the experimental results, we employed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, a non-parametric statistical measure that quantifies monotonic associations without assuming normality41. While metrics such as the Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) have been widely recommended for jointly evaluating correlation, bias, and variability42, our analysis focused on Spearman’s rank correlation as it directly assesses trend consistency across experimental sequences. This statistical measure proved particularly valuable in assessing both the repeatability of our experiments and the consistency of trends across different experimental sequences, thereby providing a rigorous evaluation of the model’s reliability.

Evaluation of key parameters using orthogonal design

Selection of key parameters and levels

Four key parameters—slope length, slope width, soil layer thickness, and material type—were selected to comprehensively evaluate their influence on model performance.

Slope length has varied considerably in previous studies. Field experiments often employ plots ranging from 5 to 20 m in length9,15,19, with some extending up to 60 m43. In contrast, laboratory models generally adopt smaller scales, typically between 1 and 5 m, with 1 m being a common standard10,16,44. In this study, we further investigate whether slope length can be reduced below 1 m while still maintaining model validity, thereby testing the potential for reliable and transferable simulation of nonpoint source pollution processes under highly compact experimental conditions.

The slope width in the soil tank has received relatively little attention in previous studies and is often overlooked, especially in larger-scale models. For ease of construction, it is typically kept as narrow as possible in these experiments16,45. For example, around 0.20–0.30 m in models with a 1-meter slope length. As our study further reduces the overall model size, we included two slope widths (0.20 m and 0.40 m) for comparative analysis.

Soil layer thickness was determined based on the concept of a mixing layer—a shallow zone where solutes are mobilized by rainfall and runoff46. This layer typically ranges from 0.01 to 0.05 m47. Accordingly, two thicknesses (0.05 m and 0.10 m) were selected for comparison.

Slope material is a key determinant of model performance48. To evaluate the effects of substrate properties, two contrasting materials were selected. While some researchers recommend using agricultural soil in scaling experiments48, we employed agricultural sandy loam soil to represent field-relevant conditions, consistent with the dominant soil type at the orchard site. In contrast, river sand was used as a homogeneous and idealized medium, commonly adopted in physical modelling for its stable infiltration behaviour and reproducibility25.

Orthogonal experimental design and parameter effect analysis

An orthogonal factorial design method was used to systematically assess the effects of key model parameters on experimental outcomes. This approach allows for efficient comparison of multiple factors and levels, ensuring balanced and comprehensive evaluation49. Treatments were arranged according to a standardized orthogonal table to achieve uniform distribution and systematic comparability. Statistical analysis, including range analysis and analysis of variance (ANOVA), was then conducted to identify optimal parameter combinations50.

In alignment with orthogonal design principles and the research objectives, slope length was set at four levels (equal intervals), while slope width, soil layer thickness, and slope material were each set at two levels (see Supplementary Table S2). To maintain simplicity and reduce experimental uncertainty, interactions between factors were not included51. A mixed-level orthogonal table (L8, 4 × 2³) was used, with slope length (L) in the first column, and width (W), thickness (T), and material (M) in the subsequent columns. The fifth column was reserved for error estimation. This resulted in eight experimental treatments (see Supplementary Table S3).

Evaluation metrics and statistical analysis

-

(1)

Evaluation metric definition.

A reference configuration was established as the control group (CG), comprising a slope length of 1.0 m, cross-sectional width of 0.4 m, soil layer thickness of 0.1 m, and agricultural soil as the substrate material. The temporal evolution of mass concentration in the CG was determined by averaging duplicated experimental runs to ensure reliability. To quantitatively assess model performance, we adopted the index of false (IF) as the primary evaluation metric. This indicator measures the deviation between experimental group (EG) and control group (CG) concentration curves, where higher IF values signify greater divergence from the control conditions. The IF is calculated as the absolute value of the integral difference between the EG and CG curves over the time interval [\(\:{t}_{0}\), \(\:{t}_{1}\)], where t0 and t1 denote the start and end time of the sampling period, respectively:

Here, \(\:f\left(t\right)\) represents the EG curve, and \(\:{f}_{0}\left(t\right)\) represents the CG curve. The calculated IF values are input into the orthogonal table for subsequent range and variance analysis.

-

(2)

Range analysis.

Range analysis was employed to evaluate parameter sensitivity in the orthogonal experimental design. For each factor j at level m, we calculated both the sum (\(\:{K}_{jm}\)) and mean (\(\:{\overline{K}}_{jm}\)) of IF values to assess factor effects systematically. The range (Rj) for each factor was computed as the difference between maximum and minimum \(\:{K}_{jm}\) values, providing a measure of factor influence magnitude.

To account for the heterogeneity in factor levels (slope length with four levels versus other factors with two levels), we implemented a correction procedure for the range analysis. The relative influence of each factor was quantified using a corrected range (\(\:{R}^{{\prime\:}}\)) derived from the following equation:

where \(\:{R}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the corrected range; \(\:R\) is the original range; r is the repetition number for each level of the factor; and d is the adjustment coefficient, which is determined on the basis of the number of levels. According to the established statistical Table50, the adjustment coefficient for slope length is 0.45, whereas for the other factors, it is 0.71.

(3) Variance analysis.

To rigorously evaluate factor significance and experimental reliability, we conducted analysis of variance (ANOVA). This statistical approach enabled quantitative assessment of both factor effects and experimental error, and the analysis steps were listed as follows.

Calculation of the sum of squares (SS): For the j-th factor, the deviation sum of squares (\(\:{SS}_{j}\)) is calculated as follows.

Here, \(\:\overline{x}\) is the average of the evaluation metric (IF values), \(\:{\overline{K}}_{ij}\) is the mean IF value for the i-th level of the j-th factor, m is the number of levels for factor j, and r is the number of repetitions for each level.

Calculation of mean square (MS) values: The mean square (MS) for each factor (\(\:{MS}_{\text{j}}\)) and the mean square error (\(\:{MS}_{\text{e}}\)) are computed. The degree of freedom (\(\:{df}_{\text{j}}\)) for each factor is equal to the number of levels (m) minus one. The sum of square error (\(\:{\text{S}\text{S}}_{e}\)) corresponds to the sum of squares deviation for the error column. The degrees of freedom of the error (\(\:{df}_{\text{e}}\)) are the total degrees of freedom (total experiments n minus one) minus the sum of the degrees of freedom for all factors.

Construction of the F statistic: Finally, the F statistic for each factor is computed as follows.

Referring to the statistical tables of50, the threshold value Fa was determined to perform the significance test. If \(\:{F}_{j}\)>Fa, the null hypothesis is rejected, indicating that the factor significantly influences the experimental results.

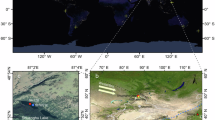

Field validation: three Gorges reservoir region case study

Experimental area

The field validation was conducted in a sloped citrus orchard within the Meixi River Basin, Fengjie County, Three Gorges Reservoir region (Fig. 2a, b). The study site is characterized by an elevation of 221 m and a slope gradient of approximately 15°. The orchard, established in 1980, features mature navel orange trees planted in a systematic 4 × 4 m grid pattern (Fig. 2c), with canopy heights ranging from 3 to 4 m. The site experiences a mid-subtropical humid monsoon climate, characterized by concentrated summer precipitation. The soil in the orchard is characterized as agricultural sandy loam soil, typical of the cultivated soils in this region. The soil profile exhibits distinctive hydrological characteristics, with a marked decrease in permeability at depths below 0.50 m (Fig. 2d), creating a natural barrier for subsurface flow.

Multi-scale characterization of the experimental site: (a) Location of the site (map created using ArcGIS 10.8, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview), (b) sloping landscape of the citrus orchard (photo captured by the authors using DJI Mavic 2, https://www.dji.com/cn/mavic-2/info), (c) experimental setup on the slope (photo captured by the authors using DJI Mavic 2), and (d) permeability boundary in the soil profile (photo by the authors).

Pre-experimental fertilization was conducted seven days prior to the trials, following standard agricultural practices, i.e., 1–1.5 kg of compound fertilizer and 5–7.5 kg of organic fertilizer per tree. This standard fertilization protocol ensured consistent nutrient conditions across all experimental plots. The experimental period was characterized by zero natural precipitation between fertilization and the initiation of simulated rainfall experiments, ensuring controlled initial soil moisture conditions and eliminating potential interferences from natural rainfall events.

Experimental setup

A systematic array of four runoff plots was established, featuring incrementally increasing lengths (4, 8, 12, and 16 m) while maintaining a constant width of 4 m. Each experimental plot was hydraulically isolated using impermeable barriers to prevent inter-plot contamination.

At the downslope end of each plot, a runoff collection system was constructed by modifying the existing drainage ditch into a collection trough. These troughs were lined with impermeable geomembrane and separated by additional barriers to ensure the integrity of collected samples. During simulated rainfall events, runoff from each plot was directed into its respective collection trough, and the total runoff volume was determined by measuring the water depth in each trough.

The artificial rainfall system comprised a four-nozzle rainfall generator, a water supply and control unit, and an adjustable support frame. A flow meter installed on the inlet pipe continuously recorded water consumption. Prior to the experiments, the frame height and nozzle configuration were calibrated to ensure uniform rainfall distribution across all plots. The rainfall intensity was maintained at a constant rate of 1.20 mm/min throughout the experiments, matching the physical model setup.

Experimental monitoring and data analysis

The experiments were conducted from 31 August to 3 September 2020, with each session commencing after 4:00 PM and only one plot was tested per day to ensure consistent and independent conditions. During each experiment, runoff generated by the simulated rainfall was collected in the designated troughs.

Runoff samples (500 mL each) were collected at 15-minute intervals, yielding five samples per session and 20 samples overall. All samples were analyzed at the Institute of Subtropical Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Sciences, to determine total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) concentrations. The source water used for simulated rainfall was also tested, with TN and TP concentrations measured at 0.74 mg/L and 1.54 mg/L, respectively.

Comparison scheme between the physical model and field observations

The physical slope model was specifically designed to closely replicate the experimental conditions of the field runoff plots in the Three Gorges orchard (Fig. 3). Both experiments used the same slope gradient (15°), rainfall intensity (1.20 mm/min), and proportional slope length (0.25–1 m in the model vs. 4–16 m in the field. In the field, fertilizer was applied evenly at one unit per 4 m. To match this setup, tracer was uniformly applied in the physical model at a rate of one unit per 0.25 m. Both experiments used agricultural sandy loam soil with comparable texture and hydrological properties. Additionally, the model’s impermeable base was intended to mimic the low-permeability characteristics of the orchard’s subsoil layer. All experimental procedures, including setup, operation, and data processing, were conducted in accordance with the methods described in the preceding sections.

Experimental comparisons between (a) the physical slope model (schematic diagram drawn by the authors) and (b) the sloped orchard in the Three Gorges Region (top-down photograph captured using DJI Mavic 2 drone, https://www.dji.com/cn/mavic-2/info).

Analysis of results

Results of soil solute transport simulations with the physical model

A total of 24 independent trials were conducted using the developed physical model apparatus. Across all trials, the temporal evolution of runoff solute concentration exhibited a consistent pattern: concentrations declined rapidly following the onset of runoff and subsequently stabilized, generally conforming to a power function (Fig. 4). Notably, in 17 out of 24 trials, the goodness-of-fit exceeded 0.90, indicating a high degree of model reliability.

Solute concentration decay curves from 24 physical model experiments. Panels (a–x) show Ex-01 to Ex-24 results under varying design parameters, black squares show observed NaCl concentrations, red lines are fitted decay models, and Adj. R2 denotes the adjusted coefficient of determination. This figure allows comparison of curve shapes and Adj. R2 values to assess consistency.

To further assess the reproducibility of the experimental results, Spearman coefficients were calculated for all pairwise comparisons among the 24 data series (Fig. 5). The analysis yielded a high average Spearman coefficient (mean = 0.893), confirming strong overall consistency in solute transport trends across experimental groups. While most pairwise comparisons demonstrated strong monotonic agreement, a few pairs showed notably lower correlations (minimum = 0.052). The low-correlation pairs are likely a direct result of the model’s high sensitivity to slope material and soil thickness, coupled with the limited number of levels tested for these factors. For example, Ex-02 (sand, 0.05 m thickness) and Ex-12 (sand, 0.10 m thickness) differ in thickness, while Ex-02 (sand, 0.05 m thickness) and Ex-20 (soil, 0.10 m thickness) differ in both material and thickness. These low-correlation pairs thus indicate the potential effect of changes in key design parameters on solute transport.

Analysis of the effects of model parameters

Description of the orthogonal experimental results

The influence of key model parameters on simulation outcomes was systematically evaluated using an orthogonal experimental design. Figure 6 presents a targeted comparison of the solute concentration decay curves for these eight groups against the control group (CG, also labeled as SC curve), which serves as the direct input for calculating the Index of False (IF) in the subsequent sensitivity analysis. The experimental results demonstrated that the temporal evolution of solute concentration in runoff for all eight experimental groups closely followed a power-law trend (Fig. 6a–h). Among these, adjusted R2 values exceeded 0.90 in Fig. 6a, c, f, and h, while Fig. 6d, e and g were in the 0.70–0.90 range, and Fig. 6b showed a lower R2 value while still exhibiting a similar decay trend, indicating robust model performance. Figure 6i shows the standard reference curve for the control group.

Solute concentration decay curves with power function fitting for the experimental groups and the control group. Panels (a–h) show the results for the eight experimental groups from the orthogonal design (Ex-03, Ex-07, Ex-13, Ex-14, Ex-18, Ex-19, Ex-20, Ex-21; for parameters see Supplementary Table S3), while panel (i) shows the standard reference (SC) curve for the control group (CG). Black squares show observed NaCl concentrations; red lines are fitted models. Adj. R2 indicates the adjusted coefficient of determination.

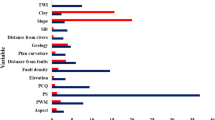

Range analysis

As shown in Table 1, the adjusted range (R′) was 101.11 for soil layer thickness (T) and 89.98 for slope material (M), identifying these as the most influential parameters in the model. The R′ value for slope length (L) was 51.93, indicating a moderate effect, whereas slope width (W) had a minimal influence, with an R′ value of 2.16. Among them, the ranges for slope length (L), thickness (T), and material (M) exceeded the error column range, confirming their significant impact on the results. In contrast, the width (W) range was smaller than the values in the error column, suggesting that width had a negligible influence on the deviation in results or that its effect was not detectable under the current experimental conditions. In conclusion, the order of factor importance was material (M) > thickness (T) > length (L) > width (W). These sensitivity results indicate that material and thickness are the most influential parameters, guiding model optimization efforts. The limited sensitivity observed for slope length within the tested 0.25–1.0 m range suggests that shortening the physical model’s slope length does not significantly alter simulation trends, supporting the feasibility of using compact experimental setups to study real-world processes.

Main effects plots (Fig. 7) illustrate the influence of each factor, with factor levels on the x-axis and Kjm values on the y-axis. Low \({\bar{K}}_{jm}\) values indicate high similarity between the experimental and control groups, indicating stable simulations. The graphs reveal that slope length (L) was variable, performing best at 0.25 m (2) and 0.75 m (3); a thickness of 0.05 m (1) was superior to 0.10 m (2); and soil (2) as a slope material outperformed sand (1), and doubling the width from 0.20 to 0.40 m had little effect on model performance.

Variance analysis

To distinguish data fluctuations caused by experimental conditions from those arising from random errors, variance analysis was applied to assess the influence of experimental factors. As indicated by statistical theory, \(\:MS\) was less than or equal to twice the \(\:{MS}_{e}\), and the variation attributed to this variable is considered comparable to the error variation. The \(\:SS\) and \(\:df\) of factors should be incorporated into the error term to recalculate the \(\:{MS}_{e{\prime\:}}\) to increase the sensitivity of the F test. In Table 2, the MS width (W) was less than twice the \(\:{MS}_{e}\), leading to its inclusion in the error term. The adjusted error (\(\:{e}^{{\prime\:}}\)) mean square was then used to compute F values for all experimental factors, which were compared against the critical value (Fa). The results showed that thickness (T) and material (M) significantly influenced the experimental outcomes, whereas length (L) and width (W) had no significant impact. This finding supports practical parameter optimization by confirming that material and thickness are the most effective factors to adjust, while also validating that reduced slope lengths can still capture representative transport behaviour when inputs are appropriately scaled.

Field observation results

Overall characteristics of nitrogen and phosphorus transport

Field experiments revealed that subsurface flow was the dominant pathway for runoff generation. Analysis of collected runoff samples showed variable trends in total nitrogen (TN) concentrations over time (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Table S4), indicating that nitrogen loss primarily occurred in soluble form and was readily transported via subsurface flow. In contrast, total phosphorus (TP) concentrations exhibited a marked decrease (Fig. 8b, Supplementary Table S5), with the greatest reductions observed in plots with longer slopes. This suggests that phosphorus was more likely to be retained in the soil, especially as slope length increased.

Temporal variation in cumulative runoff concentrations

The temporal dynamics of cumulative TN concentrations displayed an initial slight increase, followed by a decrease and then a minor rise (Fig. 9a). During the early stage (0–60 min), limited subsurface flow allowed surface-layer nitrogen to be mobilized, resulting in increased concentrations. As rainfall continued (60–120 min), dilution and leaching effects led to a decline in TN concentrations. In the later stage (120–150 min), as the soil became saturated, deeper-layer nitrogen was leached, causing a secondary increase. For TP, the temporal trends varied with slope length (Fig. 9b): longer slopes (12 m and 16 m) retained most phosphorus in the soil, while shorter slopes (4 m and 8 m) exhibited more variable retention, with intermittent peaks and declines.

Variations in pollutant loss with slope length

With increasing slope length, total nitrogen loss exhibited an upward trend (Fig. 10a, Supplementary Table S6), while nitrogen loss intensity decreased significantly (Fig. 10b Supplementary Table S7). For phosphorus, total loss initially increased with slope length but declined sharply as slope length increased from 8 to 12 m (Fig. 10a). Correspondingly, phosphorus loss intensity per unit area also decreased significantly over this range (Fig. 10b). These results highlight the complex interplay between slope length and nutrient transport, with longer slopes promoting greater overall nitrogen loss but enhancing phosphorus retention and reducing loss intensity.

Discussion

Comparisons between the physical model and actual observations

Consistency, discrepancy, and causes

In the physical slope model experiments using agricultural soil, runoff per unit area increased rapidly with rainfall, reaching a peak at approximately 10 min, after which the runoff volume stabilized (Fig. 11a, Supplementary Table S8). The relationship between total runoff and slope length in the physical model closely mirrored that observed in field experiments and previous studies, with total runoff volume increasing as slope length increased (Fig. 11b). These results are consistent with established findings that longer slopes reduce runoff time and lead to a non-uniform increase in runoff volume13,52, indicating that the physical slope model effectively captures the essential runoff dynamics of natural slopes.

After normalization, both the physical model and field data showed that total pollutant loss increased with slope length (Fig. 12a), particularly for total nitrogen loss data from field observations14, with Spearman correlation coefficients exceeding 0.9. This strong agreement further validates the model’s reliability. A key consideration in interpreting the discrepancies between the physical model and field observations is the fundamental difference in the chemicals measured. The laboratory model employed NaCl as a conservative tracer, which is ideal for simulating the transport dynamics of highly soluble, non-reactive pollutants that move passively with the water flow, such as nitrate-nitrogen. In contrast, the field measurements included total phosphorus (TP), a pollutant whose transport is strongly influenced by adsorption to soil particles and sediment, and is therefore not conservative53,54. This fundamental difference in chemical behavior is a major reason why the model successfully replicated the increasing trend of total nitrogen loss with slope length—a process dominated by soluble transport—but could not capture the subsequent decline in TP loss observed in longer field slopes, which is attributed to the increased filtration, deposition, and retention of particulate-bound phosphorus over greater distances. Therefore, while the model effectively reproduces runoff-driven trends for dissolved pollutants, caution should be exercised when interpreting results for reactive or sediment-associated contaminants.

Regarding loss intensity, field observations indicated that the nitrogen and phosphorus loss intensities decreased as slope length increased, whereas the physical model showed an opposite trend—an increase in pollutant loss intensity with slope length (Fig. 12b). The literature also reports inconsistent findings on this relationship. For example, some studies found that nitrogen loss intensity via surface runoff decreases with slope length, while sediment-associated nitrogen loss increases9. Other studies, including those with longer slopes (e.g., from 10 to 60 m43 ) or laboratory models (e.g., from 1 to 5 m14), reported increasing total nitrogen loss intensity with slope length. These discrepancies are often attributed to differences in the contributions of surface runoff and subsurface flow, as their transport mechanisms differ significantly55.

In summary, despite certain discrepancies, the physical model demonstrates high reliability in simulating hydrological and pollutant transport processes on slopes. This is further supported by the fact that 17 out of 24 experiments achieved an adjusted R2 above 0.9 for the power‒law relationship between pollutant concentration and runoff migration (Fig. 4). This consistency indicates that the model effectively captures key hydrological and transport processes at the slope scale, providing valuable trend-based insights for identifying critical slope length thresholds and informing the design and placement of interception measures. While different pollutants may exhibit distinct behaviours, the primary influence of slope length on pollutant loss risk operates through its effect on hydraulic transport pathways and residence time—a mechanism common to many dissolved pollutants. Thus, the model offers generalizable, semi-quantitative guidance for optimizing the spacing of interception structures across a range of pollutant types. Furthermore, supplementary experiments with pond interventions demonstrated that a double-pond configuration more effectively reduced both peak runoff and total solute loss than a single pond, further supporting the utility of small-scale physical models for comparing management strategies and guiding the spatial layout of runoff interception measures in real-world landscapes (see Supplementary Information “4 Pond System Simulation in the Physical Model”). These results suggest that well-designed small-scale physical models can effectively capture the key hydrological and environmental processes of sloping landscapes, even under simplified or constrained conditions.

Scale effects

The fidelity of physical models is subject to multiple factors, including materials, geometry, and scale, with scale effects being particularly crucial. Our orthogonal experiments quantitatively establish the hierarchy of parameter influence on model stability: slope material > soil thickness > slope length > slope width. Material properties and soil layer thickness emerged as the dominant factors (adjusted range R’ = 101.11 and 89.98, respectively), their impact far surpassing that of slope length (R’ = 51.93) and width (R’ = 2.16). This hierarchy suggests that during model downscaling, parameters defining the physical media (e.g., material, thickness) are more prone to inducing systematic biases than are planar geometric parameters (e.g., length, width).

Despite these scale effects, the physical model demonstrates considerable reliability in simulating specific processes. For instance, the trend of total pollutant loss as a function of slope length aligns with both field observations and previous research9,14. Nevertheless, certain complex phenomena remain challenging to replicate with high fidelity. With diminishing scale, the model cannot fully capture the redeposition phenomenon that occurs during runoff scouring8,40, a process critical for the accurate characterization of agricultural nonpoint source pollution (ANSP)56. Consequently, delineating the practical boundaries for the application of physical models is essential.

Our findings show that by optimizing key parameter configurations, the physical model can reliably reproduce macroscopic pollutant transport trends (Adj R2 > 0.9 for 5 out of 8 groups), thereby mitigating scale-induced distortions. For macro-level predictions in short-duration, high-scour scenarios, such as simulating pollutant retention in terraced wetlands or detention ponds, screening for robust parameter via orthogonal experiments presents an efficient strategy. Conversely, for detailed simulations involving long-term, multi-pathway transport processes, the potential distortions arising from scale effects must be assessed with caution.

Cost comparisons

Physical model experiments present substantial advantages in resource efficiency over traditional field observations. As detailed in Table 3, the physical model experiments significantly reduce the land area needed, the number of personnel involved, the preparation time, and the duration of each experiment. This dramatic increase in efficiency makes physical modelling a pragmatic and powerful tool, particularly for projects with constrained budgets or timelines. It presents a strategic trade-off: physical models provide rapid, directionally-correct insights essential for iterative design exploration and the preliminary screening of management strategies.

Implications for slope management design

While the orthogonal analysis statistically identified slope material as highly influential (Table 1), this is largely a result of the deliberate selection of two strongly contrasting materials (homogenized river sand vs. agricultural sandy loam soil) to test model sensitivity. From a practical design perspective, however, soil layer thickness and slope length emerge as the most actionable parameters.

The significance of slope length in the management of ANSP is well-established. It directly influences runoff generation, erosion intensity, and solute transport processes. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the relationship between slope length and solute loss is often nonlinear, with threshold values beyond which the risk of pollutant loss increases sharply9,57. In practice, conservation strategies such as terracing, ponds, vegetative filter strips, and increased ground cover are implemented to maintain slope length within an optimal range and to slow runoff, thereby reducing the risk of pollutant export20,58,59,60. Our finding that the physical model exhibits consistent sensitivity to slope length across the tested range (0.25–1.0 m) validates its utility for prototyping such slope-length-based interventions. Similarly, soil layer thickness provides a fundamental control on pollutant transport23,47,61. A shallower soil layer saturates more rapidly and offers a limited reservoir for pollutants, leading to a concentrated flush of solutes. In contrast, a deeper layer promotes dilution, extended contact time, and greater retention. This insight allows designers to strategically specify soil depth in constructed slopes to achieve desired pollution mitigation outcomes, making thickness a powerful and direct design lever.

However, these critical values are highly site-specific, depending on factors such as local soil texture, slope gradient, and vegetation cover14,18. Our small-scale physical model successfully reproduced the observed nonlinear increase in solute loss with increasing slope length, providing an experimental basis for identifying such thresholds. Although the model does not capture all scaling effects, rainfall variability, or the full range of pollutant types, this low-cost and flexible platform enables systematic exploration of site-specific responses and supports the early-stage planning of interception measures. Moreover, its simplicity and efficiency make it a practical complement to field monitoring, providing valuable guidance for conservation design under resource constraints (see Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. S3).

Limitations and prospects

Research limitations

In this study, slope physical model experiments were conducted under independent conditions following the same experimental procedures, and similar results were obtained, indicating good repeatability and reliability. However, the statistical power is constrained by a limited number of replicates. An expanded sample size would further reduce experimental errors and enhance the statistical certainty of the results.

As the primary focus of this study was validating the small-scale physical model’s applicability, only a limited number of parameters were considered. Key factors known to influence pollutant transport, such as rainfall intensity, soil physical properties (e.g., wilting point, saturated hydraulic conductivity, and field water holding capacity)44, and vegetation coverage, were not included. In particular, the rainfall regime in our experiments was simplified to a constant intensity and duration for the sake of comparability and experimental control. This approach does not fully capture the variability and complexity of natural rainfall events, such as fluctuations in intensity, duration, and peak distribution, which are known to significantly affect runoff generation and pollutant transport in the field. Moreover, field soil moisture data, which are crucial for distinguishing between surface runoff and subsurface flow62, were not collected. Future research could include soil moisture monitoring to characterize how surface runoff and subsurface flow comprehensively influence pollutant transport.

Additionally, NaCl was employed as a soluble solute tracer to simulate the transport characteristics of dissolved contaminants via runoff without considering particulate-bound pollutant loss through soil erosion. This simplification may lead to an underestimation of slope-scale redeposition effects16,40 and their regulatory impacts on pollutant loads. Future investigations could incorporate more tracers, such as fluorescent proteins or dyes, to reflect these particulate-bound pollutants and quantitatively analyze the turbidity and suspended solids in runoff samples to better characterize particulate-associated transport.

Future work

Future work should embrace the trend of using physical models not as mere imitators of real systems, but as prototypes for testing ecological theories and design strategies63. In prototype testing, the objective is not to eliminate the differences between models and real systems, but to leverage the model’s controlled environment to explore a wide range of scenarios, identify parameter trends, and evaluate alternative management approaches64.

For nonpoint source pollution management, this prototyping approach is particularly valuable. Physical models allow for the systematic isolation of influencing factors and the rapid observation of trend-based responses, providing timely scientific support for optimizing landscape practices. For example, small-scale physical models can reduce time and cost, allow for rapid adjustments of parameters, and provide explicit guidance for decision-making in landscape design. Researchers can identify the most effective landscape interventions by simulating changes in pollutant loads in areas with different slopes, vegetation cover, or rainfall conditions. This balances research precision with practical applicability, offering an effective means to address the complexity and uncertainty inherent in environmental system design.

Conclusions

This study advances the field of designed ecology by developing and validating a novel physical modelling approach for agricultural nonpoint source pollution processes in sloping landscapes. Through systematic integration of laboratory experiments and field observations, we demonstrate even highly compact scaled physical models (with slope lengths as short as 0.25 m) can reliably capture complex solute transport processes. Our findings reveal three key advances in physical modelling methodology: (1) Model reliability: Across 24 experimental sets with varying scales (0.25–1 m), runoff concentration dynamics consistently exhibited power–law behaviour (adjusted R2 > 0.90 in 17 sets), validating the model’s ability to replicate established pollutant transport patterns. (2) Parameter sensitivity: Quantitative analysis revealed a hierarchical influence of model parameters (slope material > soil layer thickness > slope length > slope width), with material properties and soil thickness emerging as statistically significant factors (P < 0.05), providing crucial guidance for model optimization. For the practical application in designed ecology, however, soil layer thickness and slope length are identified as the most critical and actionable parameters for landscape management. (3) Scale transferability: Strong correlation was observed between laboratory models (0.25–1 m) and field observations (4–16 m) in both runoff generation and pollutant transport patterns, demonstrating the model’s capability to bridge laboratory and field scales despite non-linear scaling relationships.

The physical modelling framework with scaled-down structures offers several advantages for designed ecology applications: (1) Efficient parameter optimization: The model enables rapid evaluation of design parameters such as the spatial forms of ponds and wetlands under controlled conditions, significantly reducing the time and resources required for field trials. (2) Design standardization: The validated modelling approach facilitates the development of standardized design protocols for slope-based pollution control systems, helping to promote the “traditional ecological wisdom–module identification–enhanced design–performance monitoring” pathway applied in large-scale ecological restoration with standardized modular technologies60 and supporting evidence-based landscape design and environmental management. (3) Future integration: This work lays the foundation for integrating physical modelling with field observations and mathematical simulation, creating a comprehensive toolkit for designed ecology that bridges theoretical understanding and practical implementations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sack, C. Landscape architecture and novel ecosystems: ecological restoration in an expanded field. Ecol Process 2, 35; https://doi.org/10.1186/2192-1709-2-35 (2013).

Higgs, E. Novel and designed ecosystems. Restor. Ecol. 25, 8–13 (2017).

Ross, M. R. V., Bernhardt, E. S., Doyle, M. W. & Heffernan, J. B. Designer ecosystems: incorporating design approaches into applied ecology. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 40, 419–443 (2015).

Steffen, W. et al. Trajectories of the Earth system in the anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115, 8252–8259 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Global inland-water nitrogen cycling has accelerated in the anthropocene. Nat. Water. 2, 729–740 (2024).

Fiksel, J. D. & Resilient Sustainable systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 5330–5339 (2003).

Wang, Z. Ecophronesis and actionable ecological knowledge. Urban Plann. Int. 32, 16–21 (2017).

Burt, T., Pinay, G. & Worrall, F. Howden, N. Slopes: solute processes and landforms. Memoirs 58, 191–204 (2022).

Xing, W. et al. Slope length effects on processes of total nitrogen loss under simulated rainfall. Catena 139, 73–81 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Laws Governing Nitrogen Loss and Its Numerical Simulation in the Sloping Farmland of the Miyun Reservoir. Plants 12, 2042; 10.3390/plants12102042 (2023).

Wang, Q., Wang, W. & Sheng, J. Response function model of solute transport with runoff on loess slopes. J. Hydroulic Eng. 11, 18–20 (1994).

Ma, C., Wang, Z. & Tan, Z. Experimental modelling of runoff dynamic processes on loess hillslope. Agric. Res. Arid Areas. 25, 122–125 (2007).

Kong, Y., Zhang, K. & Tang, K. Impacts of slope length on soil erosion process under simulated rainfall. Journal Soil. Water Conservation. 15, 17–20 (2001).

Qian, J. et al. Effects of different slope length and vegetation coverage on nitrogen loss in sloping land under artificial simulated rainfall. J. Soil Water Conserv. 26, 8–12 (2012).

Xing, W. et al. Mathematical model of ammonia nitrogen transport from soil to runoff on irregular slopes. J. Hydrol. 620, 129440; 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.129440 (2023).

Wang, L., Liang, T. & Zhang, Q. Laboratory experiments of phosphorus loss with surface runoff during simulated rainfall. Environ. Earth Sci. 70, 2839–2846 (2013).

Li, Q., Ding, W. & Xie, M. Dynamic characteristics of nitrogen concentration in interflow of purple soil slope under simulating rainfall condition. Soil Water Conserv In China. 9, 57–61 (2019).

Sheng, Y., Zhang, S., Li, L., Cao, Z. & Zhang, Y. Simulation of slope soil erosion intensity with different vegetation patterns based on cellular automata model. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1512973; 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1512973 (2025).

Li, T. et al. Study on the mechanism of Rainfall-Runoff induced nitrogen and phosphorus loss in hilly slopes of black soil Area, China. Water. 15, 3148; https://doi.org/10.3390/w15173148 (2023).

Wang, Z., Li, J., Peng, X., Hong, M. & Zhang, K. Habitat creation modes based on balance between water and soil and its application in ecological restoration engineering. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis. 60, 165–174 (2024).

Yu, K. Designed ecologies and their performance: an introduction. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 5909–5910 (2019).

Ahuja, L. R. Modeling soluble chemical transfer to runoff with rainfall impact as a diffusion process. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 54, 312–321 (1990).

Yuan, L., Sinshaw, T. & Forshay, K. J. Review of watershed-Scale water quality and nonpoint source pollution models. Geosciences 10, 25; 10.3390/geosciences10010025 (2020).

Xu, X., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, D. Laboratory rainfall simulations for similarity criterion of scale model on interrill erosion. J. Soil Water Conserv. 19, 25–31 (2005).

Huang, L. & Xu, G. Test Models for Hydraulic and River Engineering (Zhengzhou: Yellow River Water Conservancy Press, 2008).

Baynes, E. R. C. et al. Beyond equilibrium: Re-evaluating physical modelling of fluvial systems to represent climate changes. Earth Sci. Rev. 181, 82–97 (2018).

Reynolds, O. On certain laws relating to the regime of rivers and estuaries, and on the possibility of experiments on a small scale. In Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 57th Meeting (British Association for the Advancement of Science, Manchester, 1887).

Van Dang, H. et al. Physical model comparison of Gray and green mitigation alternatives for flooding and wave force reduction in an idealized urban coastal environment. Coast. Eng. 184, 104339; 10.1016/j.coastaleng.2023.104339 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Experimental investigation of wave Attenuation by Mangrove forests with submerged canopies. Coast. Eng. 186, 104403; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2023.104403 (2023).

Hang, C. et al. Wave Attenuation by juvenile and mature Mangrove Kandelia obovata with flexible canopies. Appl. Ocean Res. 155, 104443; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2025.104443 (2025).

Osei-Twumasi, A. & Falconer, R. A. Diffuse source pollution studies in a physical model of the Severn Estuary, UK. J. Water Resour. Prot. 1390–1403. https://doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2014.615128 (2014).

Yin, F. et al. Experimental study on the removal of pollutants from domestic wastewater in a strongly constructed wetland with an applied electric magnetic field. Water 16, 3088; 10.3390/w16213088 (2024).

Peakall, J., Ashworth, P. & Best, J. Physical modelling in fluvial geomorphology: principles, applications and unresolved issues. In The Scientific Nature of Geomorphology (ed. Rhoads, B. L. & Thorn, C. E.) 221–253 (John Wiley and Sons, 1996).

Kleinhans, M. G. et al. Quantifiable effectiveness of experimental scaling of river- and delta morphodynamics morphodynamics and stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 133, 43–61 (2014).

Ganti, V., Chadwick, A. J., Hassenruck-Gudipati, H. J., Fuller, B. M. & Lamb, M. P. Experimental river delta size set by multiple floods and backwater hydrodynamics. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501768; 10.1126/sciadv.1501768 (2016).

Ranieri, E., Gorgoglione, A. & Solimeno, A. A comparison between model and experimental hydraulic performances in a pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland. Ecol. Eng. 60, 45–49 (2013).

Mahdipanah, H., Tashakori, A., Emamgholizadeh, S. & Maroufpoor, E. An experimental study on the determination of dispersion coefficient in layered soils. Water Supply. 22, 2377–2394 (2022).

Wadsworth, J. C. The statistical description of precision conductivity data for aqueous sodium chloride. J. Solution Chem. 41, 715–729 (2012).

Shi, X., Wu, L., Chen, W. & Wang, Q. Solute transfer from the soil surface to overland flow: A review. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 75, 1214–1225 (2011).

Chen, L., Šimůnek, J., Bradford, S. A., Ajami, H. & Meles, M. B. Coupling water, solute, and sediment transport into a new computationally efficient hydrologic model. J. Hydrol. 628, 130495 (2024).

Dikbaş, F. A. New Two-Dimensional rank correlation coefficient. Water Resour. Manage. 32, 1539–1553 (2018).

Gupta, H. V., Kling, H., Yilmaz, K. K. & Martinez, G. F. Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: implications for improving hydrological modelling. J. Hydrol. 377, 80–91 (2009).

Wang, B. & Liu, G. Effects of relief on soil nutrient losses in sloping fields in hilly region of loess plateau. J. Soil Water Conserv. 5, 18–22 (1999).

Tong, J., Yang, J., Hu, B. X. & Sun, H. Experimental study on soluble chemical transfer to surface runoff from soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 20378–20387 (2016).

Tan, C. et al. Experimental and modeling study on Cr(VI) transfer from soil into surface runoff. Stoch. Env. Res. Risk Assess. 30, 1347–1361 (2016).

Ahuja, L. R. & Lehman, O. R. The extent and nature of Rainfall-soil interaction in the release of soluble chemicals to runoff. J. Env Qual. 12, 34–40 (1983).

Tian, K., Huang, C. & Zhang, G. Laboratory simulation experiment on chemical transport from soil to surface runoff. Transactions of the CSAE 25, 97–102 (2009).

Lei, A., Shi, Y. & Tang, K. Soil similarity issues in soil erosion model experiments. Chin. Sci. Bull. 41, 1801–1804 (1996).

Fisher, S. & Ronald, A. The Design of Experiments (Oliver & Boyd, 1935).

Li, Z. & Du, S. Experimental Optimization Design and Statistical Analysis (Beijing: China Science Publishing & Media Ltd, 2010).

Montgomery, D. C. Design and Analysis of Experiments (Wiley, 2017).

Moreno-De Las Heras, M., Nicolau, J. M., Merino-Martn, L. & Wilcox, B. P. Plot-scale effects on runoff and erosion along a slope degradation gradient. Water Resour. Res. 46, 475–478 (2010).

Barrow, N. J. A mechanistic model for describing the sorption and desorption of phosphate by soil. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 66, 9–18 (2015).

Asomaning, S. K. Processes and factors affecting phosphorus sorption in soils. In Sorption in 2020s (ed. Kyzas, G. & Lazaridis, N.) (IntechOpen, 2020)

Chen, L., Liu, D., Song, L., Cui, Y. & Zhang, G. Characteristics of nutrient loss by runoff in sloping arable land of Yellow-brown soil under different rainfall intensities. Environ. Sci. 34, 2151–2158 (2013).

Li, H., Zhou, J. & Zhang, M. Regime of fluvial phosphorus constituted by sediment. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1093413; 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1093413 (2023).

He, Z. et al. A Field Study for the Effects of Grass Cover, Rainfall Intensity and Slope Length on Soil Erosion in the Loess Plateau, China. Water 14, 2142; 10.3390/w14142142 (2022).

Han, Z., Shi, Z., Ni, J., Zhong, S. & Wei, C. Estimation of soil erosion to define the slope length of newly reconstructed Gentle-Slope lands in hilly mountainous regions. Sci. Rep. 9, 4676; 10.1038/s41598-019-41405-9 (2019).

Zhao, X. et al. Optimizing Straw Mulching Methods to Control Soil and Water Losses on Loess Sloped Farmland. Agronomy 14, 694; 10.3390/agronomy14040696(2024).

Yu, K. Large scale ecological restoration: empowering the nature-based solutions inspired by ancient wisdom of farming. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39, 8733–8745 (2019).

Ahuja, L. R. & Lehman, O. R. The extent and nature of Rainfall-soil interaction in the release of soluble chemicals to runoff. J. Environ. Qual. 12, 34–40 (1983).

Shi, W., Wang, M., Li, D., Li, X. & Sun, M. An improved method that incorporates the estimated runoff for peak discharge prediction on the Chinese loess plateau. Int. Soil. Water Conserv. Res. 11, 290–300 (2023).

Paola, C., Straub, K., Mohrig, D. & Reinhardt, L. The unreasonable effectiveness of stratigraphic and geomorphic experiments. Earth Sci. Rev. 97, 1–43 (2009).

Zhang, Z. & Liu, X. Control and uncertainty: towards a paradigm of prototyping. Landsc. Archit. Front. 8, 10-25 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. and X.P. wrote the main manuscript text; H.Z. and G.Z. jointly conducted the experiments. H.Z. prepared all the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhang, G. & Peng, X. A scaled physical model approach to simulate nonpoint source pollution in sloping landscapes for designed ecology. Sci Rep 15, 42726 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26701-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26701-x