Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused by vaginal microbiome dysbiosis, when beneficial Lactobacillus species are no longer dominant and are replaced by harmful anaerobic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis. In Caribbean cultures, women use plants topically, such as Argemone mexicana, to treat several vaginal infections, including BV. There has been little research into how traditional botanical extracts affect the vaginal microbiota, especially as these extracts are often prepared in different ways for the same condition. This study aims to evaluate the effect of botanical preparations using an in vitro co-culture assay with beneficial Lactobacillus species and BV-causing Gardnerella vaginalis. This is an application of an in vitro co-culture assay to assess the effect of botanical preparations on the vaginal microbiota. We hypothesized that variations in the chemical composition of these preparations would affect the composition of vaginal microbiota. Argemone mexicana extractions were tested using an in vitro co-culture method with Gardnerella vaginalis and one of three vaginal Lactobacillus species and evaluated by UPLC-qToF-MS for metabolomic chemical analysis. Aqueous extractions that did not have significant antibacterial effect compared to the control in monoculture suppressed the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis in co-culture with Lactobacillus, supporting the traditional Dominican use of this plant. These results are likely related to the presence of berberine and polysaccharides in the aqueous extractions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV), the most common gynecological infection in reproductive-age women globally1, is directly related to dysbiosis of the vaginal microbiome. BV is caused by a bacterial imbalance where beneficial Lactobacillus species are no longer dominant and are replaced by harmful anaerobic bacteria endogenous to the vaginal microbiota, including Fannyhessea vaginae, Gardnerella vaginalis, Megaphaera spp., Prevotella spp., and Sneathia spp2. Gardnerella vaginalis is considered the predominant bacterial species responsible for BV due to its biofilm production and initial attachment to vaginal epithelium3. However, recent studies have shown that heterogeneity and diversity of Gardnerella vaginalis may impact its virulence potential to cause BV4. This has led to a proposed amended description of Gardnerella vaginalis and the inclusion of three new Gardnerella spp. (Gardnerella leopoldii, Gardnerella piotii, and Gardnerella swidsinskii) that may also cause BV4.

Women with BV are at higher risk of transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as HIV as well as other adverse outcomes, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, preterm and stillborn birth, and cervical cancer1. The current recommended antibiotic treatments (e.g., clindamycin or metronidazole) for BV only provide a short-term solution. Many women (50–80%) experience recurrent BV infections within a year of completing antibiotic treatment5. This high rate of recurrence has been linked to biofilm persistence and antibiotic resistance, particularly for Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm, as well as failure to reestablish a health-optimal vaginal microbiota2,6.

Women also use home remedies, such as medicinal plants, to treat gynecological infections7. Many of these remedies are applied topically, and therefore, phytochemicals come into direct contact with the vaginal microbiota7. However, little is known about how traditionally prepared medicinal plant extracts affect BV or the vaginal microbiota, including beneficial Lactobacillus bacteria such as Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus gasseri, and Lactobacillus jensenii8,9. There have been several studies investigating the relationship between vaginal Lactobacillus and Gardnerella vaginalis, both in vitro and in vivo10,11,12,13. These studies have established that vaginal Lactobacillus can inhibit the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis through the production of lactic acid, since it grows poorly in acidic environments, and through the production of antimicrobial bacteriocins, bacterial peptides that inhibit the growth of other bacteria2,14. A study focused on the combination effect of vaginal Lactobacillus and metronidazole on Gardnerella vaginalis through an in vitro co-culture assay15. Our novel in vitro co-culture assay assesses the effect of natural product preparations on vaginal Lactobacillus and Gardnerella vaginalis.

The chemical composition of natural remedies can vary significantly based on how they are prepared16. Therefore, it is critical to understand how chemical diversity correlates with ethnobotanical preparations. Argemone mexicana L. is a plant commonly used in Caribbean traditional medicine, including by the Dominican community in New York City (NYC) to treat BV and other gynecological infections8,17,18,19. The use of this plant is culturally significant but also provides a low-cost solution for reproductive health. Dominican immigrants in NYC face obstacles in healthcare such as lack of health insurance, immigration status, and English proficiency20. BV infections are also more prevalent in many immigrant populations, including Caribbean communities, which face unique environmental and socio-economic challenges shaped by racial and ethnic disparities2,21. Our previous work established that methanolic extracts of Argemone mexicana impact Gardnerella vaginalis in single-bacterium minimal inhibitory concentration assays22. However, Dominican women who use this plant typically extract the plant in water to treat infection8. Aqueous extractions of Argemone mexicana, as they are traditionally prepared, have not been evaluated for their impact on the vaginal microbiota.

The aim of this study is therefore to test the effect of different botanical preparations of Argemone mexicana, using an in vitro co-culture assay with beneficial Lactobacillus species and BV-causing Gardnerella vaginalis. We hypothesized that chemical differences between each preparation method would influence the ratio of beneficial and pathogenic bacteria.

Results

Aqueous extracts impact Gardnerella vaginalis differently in monoculture and co-culture

Suppression of Gardnerella vaginalis monoculture by Argemone mexicana (AM) methanol, ethanol, Aq-1 (distilled aqueous), Aq-2 (acidified aqueous), and Aq-3 (heated aqueous) extracts prepared at 5 mg/mL and syringe filtered sterilized supernatant from Lactobacillus gasseri (LG supernatant), Lactobacillus jensenii (LJ supernatant), and Lactobacillus crispatus (LC supernatant). Kruskal–Wallis test with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (p ≤ 0.05) was performed with GraphPad Prism. *Represent significant differences.

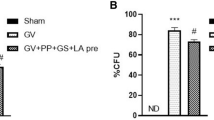

Suppression of Gardnerella vaginalis in mixed co-culture of Lactobacillus species (blue) and Gardnerella vaginalis (red) by methanol, ethanol, Aq-1 (distilled aqueous), Aq-2 (acidified aqueous), and Aq-3 (heated aqueous) extracts of Argemone mexicana (AM) prepared at 5 mg/mL. One-way ANOVA with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (p ≤ 0.05) was performed with GraphPad Prism. *Represent significant differences.

Distilled aqueous (Aq-1), acidified aqueous (Aq-2), and heated aqueous (Aq-3) extracts did not cause significant inhibition on the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis when compared to the vehicle control (1% DMSO) (Fig. 1). The tested aqueous extracts are most similar to how Caribbean women report using this plant. Lactobacillus supernatant treatments included NYC III media with each vaginal Lactobacillus grown to a dense culture, filter-sterilized, and each cell-free media (LG supernatant, LJ supernatant, and LC supernatant). The Lactobacillus supernatants had a slight inhibitory effect on Gardnerella vaginalis, but it was not statistically significant from the vehicle control (Fig. 1). Positive (ampicillin) and vehicle control treatments showed that the system was working as expected.

All three aqueous extracts of Argemone mexicana (Aq-1, Aq-2, and Aq-3) inhibited the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis when grown in mixed co-culture with Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus jensenii, and Lactobacillus crispatus, respectively (Fig. 2). Argemone mexicana extracts did not inhibit the tested Lactobacillus species in monoculture (Supplementary Fig. S1). Ethanol and Aq-2 extracts had a lower pH (pH 4) than methanol, Aq-1, and Aq-3 extracts. (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Further co-culture experiments tested the sensitivity of Gardnerella vaginalis to Aq-1 extracts (Fig. 3). Higher concentrations of the Aq-1 extract (5000 µg/mL) significantly increased the abundance of Lactobacillus gasseri. Lower concentrations of Aq-1 extract significantly reduced the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis in co-culture with Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii, respectively, compared to the negative control.

Sensitivity of Gardnerella vaginalis in mixed co-culture with Lactobacillus species (blue) and Gardnerella vaginalis (red) treated with Aq-1 (distilled aqueous) Argemone mexicana extracts ranging from 5000 µg/mL to 39.06 µg/mL. One-way ANOVA with FDR correction for multiple comparisons (p ≤ 0.01) was performed with GraphPad Prism. * Represent significant differences.

Chemical differences between organic and aqueous Argemone mexicana traditional extracts

Principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated that there were chemical variations among the five Argemone mexicana traditional extracts (Fig. 4a). The PCA model clearly showed two distinct clusters, namely organic (methanol and ethanol) versus aqueous extracts (Aq-1, Aq-2, and Aq-3), demonstrating chemical differences.

Supervised orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) analysis compared chemical features between organic and aqueous extracts (Fig. 4b). Berberine (VIP = 24.8) is the most significant chemical feature responsible for differences between the two groups. Other antimicrobial alkaloids found in Argemone mexicana, such as allocryptopine and protopine, were also identified but did not contribute significantly to the chemical differences in our OPLS-DA model22. The high reliability of the OPLS-DA model was confirmed by quality values R2XCum (0.620), R2YCum (0.995), and Q2Cum (0.928441).

Berberine is present in higher concentrations in organic Argemone mexicana extracts

UPLC-TQD-MS was used to quantify berberine in each of the extractions of Argemone mexicana. Methanol was the most efficient solvent for extracting berberine while the four other extracts contained similar concentrations (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our study assessed preparations of Argemone mexicana for their effect on pathogenic and beneficial vaginal bacteria, as they are both present in the microbiota. The in vitro co-culture method revealed results that would not have been observed in traditional antimicrobial assessments. When tested alone in monoculture, only organic extracts (methanol and ethanol) of Argemone mexicana had antimicrobial effects on Gardnerella vaginalis, while aqueous extracts (Aq-1, Aq-2, and Aq-3) had no significant effect (Fig. 1). None of the five extracts negatively impacted the growth of vaginal Lactobacillus (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results support the findings of our previous work with organic extracts of Argemone mexicana22. However, when tested in co-culture, each of the three aqueous extracts in combination with vaginal Lactobacillus species prevented the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis (Fig. 2). Furthermore, co-culture experiments with Gardnerella vaginalis and Lactobacillus gasseri or Lactobacillus jensenii, treated with serially diluted Aq-1 extracts significantly reduced the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis in comparison to the positive control streptomycin (Fig. 3). Women who prepare Argemone mexicana using traditional aqueous methods to treat gynecological infections are likely exposed to lower concentrations of phytochemicals than if they were to use more exhaustive extraction techniques (e.g. methanol or ethanol). The effect of Aq-1 extracts prepared at lower concentrations on Gardnerella vaginalis was measured to represent traditional preparations of Argemone mexicana as it is used by Caribbean women.

The difference in the effect of three aqueous extracts in monoculture and co-culture highlights the importance of assessing traditional plant extracts in a co-culture model. Standard in vitro inhibitory assessments of traditional extracts on Gardnerella vaginalis alone would have dismissed the efficacy of preparations as they are ethnobotanically used. Our results suggest that in vitro co-culture experiments build a representative model for the interaction between a drug treatment with pathogenic and beneficial bacteria in vaginal microbiota. This is consistent with previous studies on the effect of antibiotics on Gardnerella vaginalis and Lactobacillus sp. in co-culture15.

Untargeted and supervised chemical analysis revealed chemical differences between organic and aqueous extracts of Argemone mexicana and identified berberine as the most significant chemical feature between the two groups. OPLS-DA analysis was used to assess significant chemical features that distinguish organic and aqueous extracts of Argemone mexicana and, therefore, generates hypotheses of chemical differences correlated with the differential bacterial suppression of aqueous extracts in monoculture and co-culture. Berberine was identified as the most significant chemical feature and correlated with organic extracts in supervised OPLS-DA analysis (Fig. 4). This was supported by UPLC-TQD-MS quantification of berberine across the five extracts of Argemone mexicana where the methanol extract overall contained more berberine than the aqueous extracts (Fig. 5). Our previous work established that berberine inhibits the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis without inhibition of vaginal Lactobacillus and that extracts of Argemone mexicana containing higher levels of berberine trended towards better bioactivity against Gardnerella vaginalis22. In this current study, methanol extracts caused inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis in monoculture and co-culture, due in part to their higher concentrations of berberine. Ethanol extracts were not as efficient at extracting berberine, but still inhibited Gardnerella vaginalis in monoculture and co-culture23. Berberine is not the only antimicrobial compound in Argemone mexicana and there is evidence to support the potential synergistic antibacterial activity between berberine and other compounds, such as allocryptopine and protopine22,24. Ethanol extracts of Argemone mexicana likely contain other antimicrobial compounds to produce this antibacterial effect. This is also true of aqueous Argemone mexicana extracts, as they are complex mixtures containing a number of natural products that may explain their differential suppression of Gardnerella vaginalis in monoculture and co-culture. The antimicrobial effect of organic extracts containing higher concentrations of berberine is, in part, responsible for the activity seen in both monoculture and co-culture.

The differential inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis in monoculture and co-culture may be further explained by the presence of berberine. While there are not many studies on the effect of berberine and berberine-containing plants on the vaginal microbiota9, several studies have focused on their effect on the gut microbiota25,26. Like the vaginal microbiota, the gut microbiota is composed of beneficial bacteria, including Lactobacillus species. These beneficial bacteria aid in the digestion and absorption of nutrients as well as help protect against infection27. Berberine is known to alter the microbial diversity of the gut by acting similarly to a prebiotic28. Prebiotics are substances that selectively stimulate the growth or activity of a limited number of bacteria in the microbiota, while probiotics are microorganisms that positively impact the microbiota29. For example, extracts from Coptis chinensis Franch., a well-known berberine-containing plant used in Chinese traditional medicine, increased the amount of beneficial Lactobacillus species in the gut in vivo compared the untreated mice30,31. This increase was linked, in part, to the selective inhibition of bacterial species in microbiota, where pathogenic bacteria species were reduced with Lactobacillus unaffected32. These findings align with the results of this study as well as our previous work22. However, additional research suggests that berberine can also modulate the gut microbiota through other mechanisms of action28. The human microbiome synthesizes a variety of metabolites essential to normal human body function. Berberine has been shown to upregulate the production of these metabolites by gut bacteria, including those produced by Lactobacillus species, and form altered natural products with different bioactive properties33. It is likely berberine has a similar effect on vaginal Lactobacillus species as it does on gut Lactobacillus species. Berberine concentrations were higher in organic extracts, but all tested Argemone mexicana extracts contained some amount of berberine (Fig. 5). The concentration of berberine in aqueous extracts may not have been high enough to inhibit Gardnerella vaginalis but may still have impacted vaginal Lactobacillus in co-culture allowing for the inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis indirectly. It is also possible that berberine acts on Gardnerella vaginalis through alternative virulence factors. For example, our previous work established that berberine had an anti-biofilm effect on Gardnerella vaginalis22. The mechanisms of berberine and berberine-containing plants and their influence on the vaginal microbiota should be prioritized in future studies.

In addition to berberine, water is more efficient at extracting molecules with a potential prebiotic effect34. Polysaccharides, macromolecules produced by all living organisms, are well-studied for their prebiotic effect on Lactobacillus by providing a source of carbon that boosts bacterial development and survival35. Topical polysaccharide gels have shown to have a prebiotic activity and increased the abundance of vaginal Lactobacillus36,37. Water extraction, particularly heated water, is the typical method used to efficiently extract polysaccharides from plants38. Aqueous extracts of Argemone mexicana have been characterized for their polysaccharide content and are known to contain a number of polysaccharides containing arabinose, rhamnose, galactose, and galacturonic acid monosaccharides34. Although aqueous extracts of Argemone mexicana contained less berberine than methanol extracts, these extracts likely contained higher levels of prebiotic polysaccharides. These polysaccharides would provide a carbon-source for Lactobacillus to produce bacteriocins and other metabolites that would negatively impact Gardnerella vaginalis14,39. Furthermore, a study found that berberine had synergistic properties with Coptis chinensis polysaccharides in regulating the composition of the gut Lactobacillus40. Based on our monoculture (Fig. 1) and co-culture (Fig. 2) models, it is possible that the polysaccharides in combination with berberine present in aqueous extracts supported vaginal Lactobacillus as prebiotics resulting in the suppressed growth of Gardnerella vaginalis. The results of the co-culture assay with different concentrations of aqueous extracts support this conclusion, as Lactobacillus grew significantly better in co-culture with the addition of more concentrated aqueous extracts, containing higher levels of berberine and polysaccharides than with lower concentrations (Fig. 3). Consistent with this conclusion, lower concentrations of Aq-1 extracts did not inhibit the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis, but still reduced their abundance, compared to the negative control in co-culture with Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus jensenii. Future studies should continue to explore the prebiotic potential of medicinal plants as they are traditionally prepared on vaginal Lactobacillus species.

Our model suggests that the aqueous extracts in co-culture indirectly affect Gardnerella vaginalis due to the presence of berberine and polysaccharides, rather than the natural inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis by Lactobacillus species. Vaginal Lactobacillus species have a known inhibitory effect on Gardnerella vaginalis through the production of lactic acid and natural products such as bacteriocins14. In our experiments, we tested a series of controls to account for the impact of Lactobacillus on Gardnerella vaginalis. In Gardnerella vaginalis monoculture experiments, filter sterilized Lactobacillus culture supernatant treatments caused some inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis, but not significantly from the negative control (Fig. 1). In co-culture, streptomycin treatments served as a positive control for vaginal Lactobacillus and a negative control for streptomycin-resistant Gardnerella vaginalis. Overall, streptomycin treatments, which eliminated Lactobacillus species from the co-culture, allowed Gardnerella vaginalis to grow better than the vehicle control (Fig. 2). These controls supported the inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis growth by Lactobacillus but also indicated that there was not complete inhibition of Gardnerella vaginalis by vaginal Lactobacillus. This established that the inhibitory effect of aqueous extracts in co-culture was not only due to the interaction between Lactobacillus and Gardnerella vaginalis alone. The pH of Argemone mexicana extracts tested in this study was also assessed (Supplementary Fig. S2). Aq-2 and ethanol extracts were more acidic than the other extracts and Aq-2 did reduce the growth of Gardnerella vaginalis in monoculture more than the other aqueous extracts. Treatments with lower pH are generally antagonistic to Gardnerella vaginalis1, but this does not solely account for inhibition in this model. The phytochemicals of Argemone mexicana are primarily responsible for inhibiting Gardnerella vaginalis growth.

Our methodology was designed to best assess the impact of Argemone mexicana extracts on Gardnerella vaginalis rather than the effect of Lactobacillus on Gardnerella vaginalis. It takes longer (48 h) for Gardnerella vaginalis to reach exponential growth than the tested vaginal Lactobacillus species (24 h)41,42. Our co-culture model accounted for this by allowing Gardnerella vaginalis to grow to an exponential phase before adding Lactobacillus cultures and treatments. This methodology allowed us to test the effect of Argemone mexicana extracts in co-culture without Lactobacillus completely outcompeting Gardnerella vaginalis due to its growth rate. Comparison between Argemone mexicana treatments in Lactobacillus monoculture indicated that there was no significant difference in the growth of Lactobacillus between the negative control and organic or aqueous extracts (Supplementary Fig. S1). This result eliminated the possibility that aqueous extracts alone significantly enhanced just the growth of Lactobacillus, which would allow it to outcompete Gardnerella vaginalis in co-culture.

This study did not investigate the cytotoxicity of Argemone mexicana extracts on the vaginal epithelium. Previous research has indicated that Argemone mexicana and its related alkaloids exhibit cytotoxicity against cancerous cell lines, such as NUGC, HONE-1, and HepG243. To more fully understand the therapeutic potential of the traditional preparations of Argemone mexicana further research should establish its effect on healthy vaginal epithelial cells.

Our study aimed to understand and potentially validate Argemone mexicana as it is ethnobotanically used to treat BV. The results of our study support the importance of our novel in vitro co-culture model for assessing plant extracts used for the treatment of BV. Antimicrobial testing by conventional monoculture methods would not have identified the therapeutic potential of Argemone mexicana aqueous extracts as they are traditionally prepared. The differential suppression Gardnerella vaginalis by Argemone mexicana aqueous extracts in monoculture and co-culture can likely be explained by the effect of berberine and polysaccharides on vaginal Lactobacillus, although this topic warrants further scientific investigation. In vitro assessments of medicinal plants as they are prepared ethnobotanically are essential for providing useful information to people who use these plants to support their reproductive health. The results of this study help to validate the ethnobotanical use of Argemone mexicana for the treatment of BV and other gynecological infections.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and sample preparation

Plant samples of Argemone mexicana were sourced from: (1) a botánica (Caribbean healing shop) in NYC; (2) collected in the wild in Miami, Florida; and (3) obtained from greenhouses at Lehman College in the Bronx, NY (Supplementary Table S1). Wild-collected material was collected with permission at Miami Beach Botanical Garden. All collections complied with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction. Each collection was extracted with five different solvents: methanol, ethanol, distilled aqueous (Aq-1), acidified aqueous (Aq-2), and heated aqueous (Aq-3). 0.5% HCl was added for Aq-2 extracts44. Aq-3 extracts were brought to a boil on a hot plate for 30 min. The aqueous extractions attempt to mimic common traditional preparations, while alcohol extractions are more exhaustive preparations. All plant specimens were identified taxonomically based on morphology and validated by comparison with the biocultural collections at the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) samples by authors E.V. and I.V. to produce voucher specimens. Voucher specimens for each sample were prepared and deposited in the NYBG Steere Herbarium (NY) and are publicly available in the C.V. Starr Virtual Herbarium (https://sweetgum.nybg.org). Plant material was frozen with liquid nitrogen, extracted in their respective solvents, filtered, and dried under nitrogen gas to produce a powder extract. All extracts were kept in a − 80 C freezer. For UPLC analysis, powdered extracts were prepared at 2 mg/mL in 80% aqueous methanol containing 2 µg/mL caffeine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as an internal standard. For microbiological experiments, powdered extracts were redissolved in 2% DMSO (Sigma Aldrich). For metabolomic experiments, samples were dried, redissolved in 80% methanol, syringe filtered.

Chemicals

A reference standard for berberine (2.02_336.1245 m/z; 1.24 ppm) was used to compare the retention time and MS data with identified compounds. Berberine was purchased from Shyuanye Biotechnical Company (China). Extracts were prepared at 2 µg/mL in 80% aqueous methanol for UPLC analysis and compound identification via co-injection.

UPLC-QTOF-MSE analysis

UPLC separation was conducted using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC System (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC C18 column (AQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column; 2.1 mm x 50 mm x i.d. 1.7 μm). MassLynx software was utilized to control the UPLC-TQD-MSE Analysis. The flow rate was set at 0.5 mL/min, with the mobile phase consisting of (A) 0.1% aqueous formic acid and (B) acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. A gradient elution profile was implemented as follows: from 0 to 14.40 min, 90 − 0% A; from 14.40 to 17.40 min, 100% B; from 17.4 to 17.5 min, 0–90% A; and from 17.50 to 21.50 min, 90% A. The column temperature was maintained at 40 °C. Each extract was analyzed in triplicate with 2 µL injections, including needle overfill. Lock mass correction was achieved using a leucine-enkephalin solution. Electrospray ionization (ESI+) was performed in positive polarity mode. The settings included: sample probe capillary voltage at 2.5 kV; sampling cone voltage at 50 V; extraction cone voltage at 4 V; source temperature at 100 °C; and desolvation temperature at 250 °C. Nitrogen was used for the desolvation flow at a rate of 800 L/h. Data acquisition was carried out via MSeover a mass range of 100–1500 Da, with a scan time of 0.2 s. Three injections were made for each sample, including blanks, and the order was randomized prior to data acquisition. LC-MS data analysis was performed using Progenesis QI (Waters Corporation) and EZ info (Waters Corporation) for metabolomics evaluation.

UPLC-TQD-MS analysis

A Waters ACQUITY UPLC paired with a TQD triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) was utilized for the targeted analysis of the bioactive alkaloid berberine. The separations were carried out using the same column as in the earlier UPLC-QTOF-MS analysis. The mobile phases consisted of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing 0.2% (v/v) formic acid. A linear gradient elution was applied as follows: from 0 to 4.0 min, 10–35% B; from 4.0 to 9.0 min, 35% B; from 9 to 9.1 min, 35 − 10% B; and from 9.1 to 12.5 min, 10% B. The flow rate was set at 0.5 mL/min, with an injection volume of 2 µL in triplicate. MS data were collected in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using a Waters TQDMS equipped with an ESI source, operated in positive mode. The capillary voltage was set to 3.8 kV, the source temperature was maintained at 147 °C, the desolvation temperature was 250 °C, with cone gas flow at 0 L/h and desolvation gas flow at 500 L/h. MRM conditions for berberine (336.0839 → 320.34; cone voltage: 48 V) were automatically generated by Waters IntelliStart and manually reviewed to ensure appropriate selection of product ions and collision energy. A dwell time of at least 0.025 s was set for the MRM transition. The calibration curve for berberine (R2 = 0.9966) ranged from 20 µg/mL to 2e-5 µg/mL, with a sample and standard injection volume of 2 µL. Data processing was performed using Waters MassLynx 4.1 and QuanLynx software, and the data was imported into GraphPad Prism for interpolation of the standard curve and determination of unknown sample concentrations, calculated with a 95% confidence interval.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Lactobacillus crispatus (ATCC 33820), Lactobacillus gasseri (ATCC 33323), and Lactobacillus jensenii (ATCC 25258) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). A streptomycin-resistant strain of Gardnerella vaginalis (JCP8151B) was provided by Dr. Amanda Lewis from the University of California San Diego. For each experiment, Gardnerella vaginalis was grown as previously reported45, more specifically, in NYC III media (1.5% (w/v) tryptone (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5% glucose (Sigma Aldrich), 0.24% HEPES (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5% NaCl (Sigma Aldrich), 0.38% yeast (BD, Mississauga, Ontario) adjusted to pH 7.3 and supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) for 48–72 h under anaerobic conditions at 37° C with approximately 5% CO2 using BD GasPak EZ (BD) without shaking. All other Lactobacillus species were also grown in NYC III media for 24 h under the same anaerobic conditions.

Monoculture and co-culture assays

For monoculture assays with Gardnerella vaginalis, 125 µL streptomycin-resistant Gardnerella vaginalis dense cultures in NYC III media were adjusted to the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) 0.04 and added to a Corning Costar flat bottom 24-well cell culture plates (Tewksbury, Massachusetts). After 48 h, plant extracts prepared to a concentration of 5 mg/mL and diluted into the bacterial culture mixture as needed. Argemone mexicana plant extracts had established antimicrobial activity against Gardnerella vaginalis at 5 mg/mL22. For Lactobacillus monoculture, Lactobacillus cultures were adjusted to OD600 0.04 and mixed with plant extracts. After 24 h, colony-forming units (CFUs) for each of the culture were determined by plating on both MRS agar (Sigma Aldrich) plates for Lactobacillus species growth and ATCC NYC III agar plates with streptomycin (1 mg/mL) for Gardnerella vaginalis growth (Supplementary Table S2). For both experiments, the vehicle control was 1% DMSO and inoculum. The positive control was 0.02 mg/mL ampicillin (Sigma Aldrich) antibiotic treatment dissolved in 1% DMSO.

For co-culture assays, the same methodology for Gardnerella vaginalis monocultures was used. Post 48 h, 125 µL Lactobacillus cultures adjusted to OD600 0.04 in NYC III media and plant extracts were mixed to Gardnerella vaginalis to perform co-culture. After 24 h, CFUs for each of the culture were determined by plating on both MRS agar (Sigma Aldrich) plates for Lactobacillus species and ATCC NYC III agar plates with streptomycin (1 mg/mL) for Gardnerella vaginalis (Supplementary Table S3). The vehicle control was 1% DMSO and inoculum. The positive control was 0.02 mg/mL ampicillin dissolved in 1% DMSO and inoculum. An additional positive control, 1 mg/mL streptomycin was also used to account for streptomycin-resistant Gardnerella vaginalis.

Three replicates of each treatment were conducted for each of the three Argemone mexicana plant collections. CFU counts were subjected to ROUT with Q = 1% to correct for outliers using GraphPad Prism. One-way ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests followed by FDR correction for multiple comparisons was performed using GraphPad Prism.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Argemone mexicana

- Aq1:

-

Distilled aqueous extract of Argemone mexicana

- Aq2:

-

Acidified aqueous of Argemone mexicana

- Aq3:

-

Heated aqueous of Argemone mexicana

- BV:

-

Bacterial vaginosis

- CFU:

-

Colony forming units

- NYBG:

-

New York Botanical Garden

- NYC:

-

New York City

- UPLC-qToF-MS:

-

Ultra high-performance time-of-flight mass spectrometer

- UPLC-TQD-MS:

-

Ultra high performance triple quadrupole mass spectrometer

References

Coudray, M. S. & Madhivanan, P. Bacterial vaginosis—A brief synopsis of the literature. EJOG. 245, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.12.035 (2020).

Abbe, C. & Mitchell, C. M. Bacterial vaginosis: A review of approaches to treatment and prevention. Front. Reprod. Health. 5, 1100029. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2023.1100029 (2023).

Machado, A. & Cerca, N. Influence of biofilm formation by Gardnerella vaginalis and other anaerobes on bacterial vaginosis. JID 212, 1856–1861. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv338 (2015).

Castro, J., Jefferson, K. K. & Cerca, N. Genetic heterogeneity and taxonomic diversity among Gardnerella species. Trends Microbiol. 28, 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.10.002 (2020).

Safwat, F., Safwat, S., Daka, N., Sivanathan, N. & Lazarevic, M. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis: A case report and review of management. Cureus 15, e37348. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37348 (2023).

Castro, J. et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of Gardnerella vaginalis biofilms vs. planktonic cultures using RNA-seq. NPJ Biofilms Microb. 3, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-017-0012-7 (2017).

Andel van, T., Boer de, H. & Towns, A. Gynaecological, Andrological and Urological Problems. In Ethnopharmacology (eds M Heinrich & A.K. Jäger) 199–212 (2015).

Vardeman, E. & Vandebroek, I. Caribbean women’s health and transnational ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 76, 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-021-09526-3 (2022).

Mohankumar, B., Shandil, R. K., Narayanan, S. & Krishnan, U. M. Vaginosis: Advances in new therapeutic development and microbiome restoration. Microb. Pathog. 168, 105606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105606 (2022).

Andreeva, P., Shterev, A. & Danova, S. Antimicrobial activity of vaginal lactobacilli against Gardnerella vaginalis and pathogens. IJARBS. 3, 200–207 (2016).

Atassi, F., Brassart, D., Grob, P., Graf, F. & Servin, A. L. Lactobacillus strains isolated from the vaginal microbiota of healthy women inhibit Prevotella Bivia and Gardnerella vaginalis in coculture and cell culture. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 48, 424–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00162.x (2006).

Breshears, L. M., Edwards, V. L., Ravel, J. & Peterson, M. L. Lactobacillus crispatus inhibits growth of Gardnerella vaginalis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae on a Porcine vaginal mucosa model. BMC Microbiol. 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0608-0 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Inhibitory effect of Lactobacillus gasseri CCFM1201 on Gardnerella vaginalis in mice with bacterial vaginosis. Arch. Microbiol. 204, 315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-022-02896-9 (2022).

Amabebe, E. & Anumba, D. O. C. The vaginal microenvironment: the physiologic role of Lactobacilli. Front. Med. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00181 (2018).

Lee, C. Y. et al. Quantitative modeling predicts mechanistic links between pre-treatment microbiome composition and metronidazole efficacy in bacterial vaginosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 6147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19880-w (2020).

Kulakowski, D. et al. Traditional preparation of Phaleria nisidai, a Palauan tea, reduces exposure to toxic daphnane-type diterpene esters while maintaining Immunomodulatory activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 173, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.023 (2015).

Vandebroek, I. & Picking, D. Argemone mexicana. In Popular Medicinal Plants in Portland and Kingston, Jamaica 45–54 (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

TRAMIL. TRAMILibrary: Program of Applied Research to Popular Medicine in the Caribbean (2020). http://www.tramil.net/

Vandebroek, I. et al. The importance of botellas and other plant mixtures in Dominican traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 128, 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.013 (2010).

Bouilly, R. et al. Maternal and child health inequalities among migrants: the case of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. RPSP/PAJPH 44 https://doi.org/10.26633/rpsp.2020.144 (2020).

Maldonado, S. The folkloric practices of Dominican women in managing bacterial vaginosis. NWH 28, 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2023.10.003 (2024).

Vardeman, E. T., Cheng, H., Vandebroek, I. & Kennelly, E. J. Caribbean medicinal plant Argemone Mexicana L.: metabolomic analysis and in vitro effect on the vaginal microbiota. J. Ethnopharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2024.118830 (2024).

Liu, B., Li, W., Chang, Y., Dong, W. & Ni, L. Extraction of berberine from rhizome of Coptis chinensis Franch using supercritical fluid extraction. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 41, 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2006.01.034 (2006).

Zielińska, S. et al. & Matkowski, A. Screening papaveraceae as novel antibiofilm natural-based agents. Molecules. 26 (2021).

Mehraban, M. S. A., Aghabeiglooei, Z., Atlasi, R., Namazi, N. & Ayati, M. H. Berberine as a natural modifier of gut microbiota to promote metabolic status in animal studies and clinical trials: A systematic review. TCIM https://doi.org/10.18502/tim.v8i2.13086 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Effects of berberine on the gastrointestinal microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 588517. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.588517 (2021).

Jandhyala, S. M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H. & Sasikala, M. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 8787–8803. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8787 (2015).

Habtemariam, S. Berberine Pharmacology and the gut microbiota: A hidden therapeutic link. Pharmacol. Res. 155, 104722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104722 (2020).

Floch, M. H. Probiotics and prebiotics. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (N Y). 10, 680–681 (2014).

Zhou, R. et al. Coptis chinensis and berberine ameliorate chronic ulcerative colitis: an integrated microbiome-metabolomics study. Am. J. Chin. Med. 51, 2195–2220. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0192415X23500945 (2023).

Zhang, W., Xu, J. H., Yu, T. & Chen, Q. K. Effects of berberine and metformin on intestinal inflammation and gut microbiome composition in db/db mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 118, 109131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109131 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Structural changes of gut microbiota during berberine-mediated prevention of obesity and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed rats. PLoS One. 7, e42529. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042529 (2012).

Cheng, H., Liu, J., Tan, Y., Feng, W. & Peng, C. Interactions between gut microbiota and berberine, a necessary procedure to understand the mechanisms of berberine. J. Pharm. Anal. 12, 541–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2021.10.003 (2022).

Dénou, A. et al. Isolation, characterisation and complement fixation activity of acidic polysaccharides from Argemone mexicana used as antimalarials in Mali. Pharm. Biol. 60, 1278–1285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2022.2089691 (2022).

Nowak, R., Nowacka-Jechalke, N., Juda, M. & Malm, A. The preliminary study of prebiotic potential of Polish wild mushroom polysaccharides: the stimulation effect on Lactobacillus strains growth. Eur. J. Nutr. 57, 1511–1521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1436-9 (2018).

Hu, K. T. et al. Directed shift of vaginal microbiota induced by vaginal application of sucrose gel in rhesus macaques. IJID 33, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.040 (2015).

Khazaeian, S. et al. Comparing the effect of sucrose gel and metronidazole gel in treatment of clinical symptoms of bacterial vaginosis: A randomized controlled trial. Trials 19, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2905-z (2018).

Nemzer, B. V., Kalita, D., Yashin, A. Y., Nifantiev, N. & Yashin, Y. In vitro antioxidant activities of natural polysaccharides: an overview. J. Food Res. 8, 78. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v8n6p78 (2019).

Pranckutė, R., Kaunietis, A., Kuisienė, N. & Čitavičius, D. J. Combining prebiotics with probiotic bacteria can enhance bacterial growth and secretion of bacteriocins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 89, 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.05.041 (2016).

Wang, X., Liang, F., Dai, Z., Feng, X. & Qiu, F. Combination of Coptis chinensis polysaccharides and berberine ameliorates ulcerative colitis by regulating gut microbiota and activating AhR/IL-22 pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 318, 117050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2023.117050 (2024).

Machado, D., Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A. & Cerca, N. Optimization of culture conditions for Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm formation. J. Microbiol. Methods. 118, 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2015.09.007 (2015).

Argentini, C. et al. Evaluation of modulatory activities of Lactobacillus crispatus strains in the context of the vaginal microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e02733–e02721. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.02733-21 (2022).

Rubio-Pina, J. & Vazquez-Flota, F. Pharmaceutical applications of the benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from Argemone Mexicana L. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 13, 2200–2207. https://doi.org/10.2174/15680266113139990152 (2013).

Teng, H. & Choi, Y. Optimum extraction of bioactive alkaloid compounds from rhizome coptidis (Coptis chinensis Franch.) using response surface methodology. Solvent Extr. Res. Dev. Jpn. 20, 91–104. https://doi.org/10.15261/serdj.20.91 (2013).

Machado, D. et al. Thymbra capitata essential oil as potential therapeutic agent against Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm-related infections. Future Microbiol. 12, 407–416. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2016-0184 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The transnational Dominican community in NYC holds sole ownership over their traditional knowledge and biocultural heritage. The authors would like to acknowledge the Miami Beach Botanical Garden and the Florida Native Plants Society, in particular Ms. Riki Bonnema, for their contribution of plant material to this project. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant number: 1F31 AT011471-01A1] and The Garden Club of America Anne S. Chatham Fellowship for Medicinal Botany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.T.V. conducted the experiments, analyzed and visualized the data, and prepared the original manuscript. E.T.V., H.C., I.V., and E.J.K. designed the study and methodology and reviewed the manuscript. E.T.V, I.V., and E.J.K. acquired project funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vardeman, E.T., Cheng, HP., Vandebroek, I. et al. The effects of the Caribbean medicinal plant Argemone mexicana on Gardnerella vaginalis using a co-culture method with vaginal Lactobacillus spp.. Sci Rep 16, 1553 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26731-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26731-5