Abstract

Resistance spot welding (RSW) of aluminum is widely applied in lightweight vehicle body manufacturing; however, the irregular oxide layer on aluminum surfaces degrades weld quality and limits the predictability of joint performance. To address this issue, this study proposes a machine learning (ML)-based model incorporating contact voltage as a key variable to improve the accuracy of tensile strength prediction in aluminum RSW. Experimental data, including preheating current, welding current, and electrode force, were analyzed in a time-series framework, with particular emphasis on monitoring contact voltage between materials to enhance prediction performance. The results demonstrate that the ML model considering contact voltage reduces prediction error by approximately 30% compared with conventional models, thereby significantly improving the accuracy of tensile strength prediction. These findings highlight that contact voltage measurement is a critical factor for evaluating aluminum RSW quality and suggest its practical contribution to quality assurance in automotive body manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistance spot welding (RSW) is a joining process in which a high current is applied through electrodes for a short duration, generating resistive heating at the faying interface to form a localized molten zone (nugget), which solidifies under sustained pressure. Due to these characteristics, RSW enables rapid and stable welding and is primarily used for joining two metal sheets. Compared with other welding processes, it offers the advantages of a relatively simple system configuration, excellent surface quality, and high joint strength, leading to its widespread application in the manufacturing of various mechanical components. Furthermore, RSW can be applied to a wide range of metallic materials, and in recent years, its application to aluminum alloy spot welding has increased significantly, particularly for lightweight automotive body structures1,2.

However, welding of aluminum alloys using RSW faces considerable challenges due to their high thermal conductivity, high coefficient of thermal expansion, low melting point, and the formation of a surface oxide layer3. In particular, this oxide film is distributed non-uniformly across the surface and acts as a major obstacle to weld quality degradation4. Specifically, aluminum oxide has a higher melting point and higher contact resistance than the base metal, which deteriorates weld quality5. In addition, the oxide layer increases contact resistance, thereby reducing electrode life and causing process delays6. Ihsan et al. investigated various surface treatments to improve surface roughness and analyzed their effects on resistance, strength, nugget formation, and hardness4. To address the issues arising from the oxide film, various welding methods have been proposed.

Representative methods for improving the quality of aluminum resistance spot welding (RSW) include preheating7, step force8,9,10, and post-heating8,11. Preheating can enhance weld quality by homogenizing the distribution of surface oxides on aluminum, thereby reducing variations in contact resistance. Since surface roughness affects resistance, minimizing the associated heat input fluctuations is beneficial for ensuring stable weld quality7. Step force reduces resistance variation caused by surface asperities between materials. With increasing applied force, the contact area at the faying interface expands, leading to reduced resistance fluctuation and more uniform weld quality9. Although microcracks may form inside the weld, post-pressurization can suppress such defects by applying pressure to the molten pool10. In addition, post-heating may alter the weld microstructure, influencing weld strength8. Other studies have also investigated modifying electrode geometry to control resistance1,3.

Despite extensive research on improving weld quality, it remains impractical to conduct exhaustive quality verification for all products. Accordingly, nondestructive testing methods for weld quality assessment are essential. In general, parameters such as current, voltage, force, and displacement are monitored to predict the quality of RSW joints. For example, expulsion of molten metal, a phenomenon indicative of weld defects, can be identified from electrode displacement, and it often results in strength reduction due to material loss. Moreover, dynamic resistance, calculated from current and voltage, has been widely used for weld quality analysis. In the case of steels, dynamic resistance has been employed to explain nugget formation mechanisms and to predict weld strength, and its variation with weld location has also been analyzed for quality evaluation.

In addition to time-series monitoring of welding signals, studies have been conducted to predict weld strength and failure modes based on welding input variables. However, for aluminum, the variation pattern of dynamic resistance differs from that of steels, making direct application difficult and feature extraction challenging19. To overcome these limitations, machine learning (ML) approaches have been introduced to predict tensile shear load or nugget diameter as functions of welding conditions20. Furthermore, advanced data-driven approaches such as principal component analysis (PCA)21, data mining22, and deep learning techniques23,24 have been applied for quality prediction. Nevertheless, considering the pronounced influence of surface oxides in aluminum welding, systematic analysis and utilization of contact voltage—which is closely related to weld quality—remain insufficient.

Therefore, this study aims to predict the tensile strength of aluminum resistance spot welds to evaluate weld quality based on measured time-series data. Most previous studies on RSW quality prediction have primarily relied on monitoring current and voltage between electrodes. In contrast, the present work introduces contact voltage as a novel approach. Unlike conventional dynamic resistance, which includes all resistance components in the welding circuit, contact voltage is directly measured at the faying interface between aluminum sheets. Thus, it excludes voltage drops across the electrode-material interfaces and better reflects interfacial phenomena such as oxide breakdown and nugget initiation. This is particularly important for aluminum RSW where the oxide layer at the faying interface is the primary factor affecting weld quality variation. By leveraging its high sensitivity for feature extraction, we sought to improve prediction accuracy. To this end, a monitoring system was developed, and time-series features suitable for ML analysis were extracted. Subsequently, ML models were employed to predict weld quality, and all models were evaluated using MATLAB. Finally, the results obtained with and without contact voltage monitoring were compared to analyze the influence of contact voltage on tensile strength. This ML-based tensile strength prediction can serve as a key algorithm for quality decision-making in production lines.

Experiment condition and method

Measurement system setup and welding condition

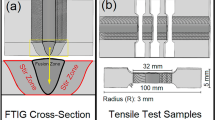

The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Welding was performed using a spot welding machine integrated with an industrial six-axis robot. In RSW, adhesion of the pressurized electrodes to the base material can alter the measured current and voltage signals. To minimize the influence of electrode adhesion on measured signals, a monitoring system was implemented to measure the contact voltage between sheets, as indicated by the blue line in Fig. 1(a). Unlike conventional dynamic resistance, contact voltage is directly measured at the faying interface between aluminum sheets. Thus, it excludes voltage drops across the electrodes and better reflects interfacial phenomena such as oxide breakdown and nugget initiation. Figure 1 schematically illustrates this difference.

Experimental data were acquired using an NI-9221 C-series data acquisition (DAQ) device. The NI DAQ system, consisting of a module and chassis, provides eight single-ended input channels for connection with various sensors. It also controls system timing and data processing to ensure consistent acquisition across all signals. In this study, current, voltage, and contact voltage were each measured at a sampling rate of 50 kHz. All signals were transmitted via USB 3.0 to a laptop for processing and storage in LabVIEW.

Figure 1(b) shows the actual measurement system. The aluminum sheets were fixed with a jig, and a wire was connected to the upper sheet to measure contact voltage. Current was measured using a Rogowski coil16, and voltage was obtained by attaching clamps to each electrode. From these three signals, features were extracted, and the parameters exhibiting the highest correlation with tensile strength were identified and used as inputs for the ML prediction model.

Tensile tests were conducted in accordance with KS B 0854 standards using specimens of 100 mm × 30 mm with a thickness of 1 mm. Welding conditions are shown in Fig. 2, with welding time, preheating time, and pressurization time kept constant. As summarized in Table 1, preheating current, welding current, and electrode force were varied. Although variables such as preheating time, welding time, and post-pressurization are also important, they were fixed at the conditions that yielded the smallest variation and the highest tensile strength based on preliminary experiments, which were designed with reference to prior studies and industrial partner field conditions. In addition, cooling time was fixed at 100 ms, as tensile strength was found to be insensitive to durations exceeding 100 ms7.

For each signal x(t) including current, voltage, and contact voltage, discrete signals xi= x(iΔt) were obtained by sampling at 50 kHz, where Δt = 20 µs. Statistical features were extracted using the following mathematical expressions:

where xmean, xmax, and tmax represent the mean value, maximum value, and time-of-peak, respectively. The time-of-peak feature (tmax) was extracted using the argmax operation, which identifies the time index at which the signal reaches its maximum within each process window. N denotes the total number of samples in each process window. Time windows were established based on the welding sequence illustrated in Fig. 2. The preheating window consisted of 20 ms corresponding to the preheating current application phase. A cooling window of 100 ms was implemented between the preheating and main welding phases. The welding window comprised 50 ms during which the main welding current was applied. With a sampling rate of 50 kHz, the system acquired 1,000 samples during the preheating window and 2,500 samples during the welding window, providing sufficient temporal resolution for robust feature extraction.

Feature extraction method

Figure 3 illustrates the data preprocessing and feature extraction method for weld strength prediction. As shown in Fig. 3(a), current signals were used to extract features such as the maximum current (Imax), mean current (Imean), and the time at which the peak current occurred (TImax). The same procedure was applied to voltage (Vmax, Vmean, TVmax) and contact voltage (CVmax, CVmean, TCVmax), and feature extraction was performed for both preheating and welding signals. As a result, a total of 18 features were obtained from a single welding process (preheating and welding), as shown in Fig. 3(b). These extracted features were then utilized to conduct experiments on weld quality prediction.

Various parameters such as time, current, mean values, and slopes have been commonly employed as feature extraction methods for predicting tensile strength in spot welding22,25,26. For instance, Boersch et al.22 predicted weld quality by using the maximum and minimum values within time segments and the differences between these values in the time-series signals. Other studies have applied not only peak and valley values but also the time at which the signal reached these points and the corresponding slopes as features25,26. Accordingly, in this study, feature extraction methods previously employed in the literature were applied.

Results and discussion

Tensile force variation based on welding conditions

Figure 4 presents the tensile test results. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the variation in tensile strength decreases with increasing electrode force. The surface oxide layer exerts a significant influence on aluminum RSW. At higher electrode forces, the effect of interfacial surface roughness is reduced, thereby decreasing resistance variation7. Figure 4(b) illustrates the variation in tensile strength with welding current. As welding current increases, the heat input rises, leading to a larger nugget size. Since tensile strength is proportional to nugget size, it increases accordingly27. Interfacial fracture occurs at lower currents, such as 22 kA, whereas expulsion occurs at higher currents, such as 31 kA. Because interfacial fracture involves limited energy absorption, it is unsuitable for automotive applications28.

As shown in Fig. 4(c), a preheating current of 10 kA yields the highest tensile strength with the smallest variation. Preheating current mitigates the influence of the oxide layer between materials. However, at 12 kA, tensile strength decreases and variation increases. This is attributed to the unstable nugget formation caused by reduced resistance, as illustrated in Fig. 4(d), where bonding occurs between the materials during welding.

Figure 5 shows the data measured to verify the occurrence of interfacial melting. Welding current was fixed at 28 kA, and the variations in current and voltage were observed under different preheating conditions. Figure 5(a) presents the current signals, confirming the changes in preheating current. In contrast, Fig. 5(b) indicates that while voltage changes with preheating current, welding voltage decreases at 12 kA. This reduction in voltage reflects decreased resistance due to interfacial melting, even at the same welding current. Therefore, to achieve stable tensile strength in the weld, both preheating current and duration must be carefully adjusted to optimize heat input.

Machine learning results

To predict the tensile test results, additional experimental data were collected. The welding current was set in the range of 25–31 kA, and the preheating current was adjusted between 8 and 10 kA. Welding conditions that resulted in interfacial fracture or exhibited large tensile strength deviations were excluded from data collection. For each condition, five specimens were prepared, and tensile tests were performed on all specimens. Data partitioning was performed in MATLAB using k-fold cross-validation with k set to 5. In this approach, the dataset is evenly divided into k folds, which are alternately used as validation and training sets. The average validation loss provides an estimate of the generalization error, thereby maximizing data utilization efficiency. In addition, random shuffling was applied to prevent bias arising from data order and to mitigate potential overfitting.

Machine learning was implemented using MATLAB’s simple linear regression model. Although MATLAB supports regularized linear regression methods such as Lasso and Ridge, as well as hyperparameter tuning through Bayesian optimization, the simple linear regression model employed in this study estimated regression coefficients using the closed-form solution of ordinary least squares (OLS). OLS minimizes the sum of squared residuals without regularization and does not require hyperparameters.

Simple linear regression is a statistical technique that models the dependent variable as a linear combination of one or more independent variables. Its model structure is intuitive, easy to interpret, and computationally efficient, making it suitable for small datasets. Moreover, regression coefficients provide quantitative insights into the influence of each independent variable, facilitating engineering interpretation and physical understanding. In material property prediction problems where linear relationships among variables are evident, linear regression reduces the risk of overfitting and often achieves superior generalization compared with complex nonlinear models. Other regression algorithms commonly applied in ML include Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and tree-based methods. However, as shown in Table 2, after testing multiple models, the linear regression model was ultimately selected due to its lowest prediction error.

Figure 6(a) and (b) present the data before and after incorporating contact voltage, respectively. The comparison demonstrates that error decreases when contact voltage is included, consistent with the experimental setup, where measuring interfacial contact voltage minimized the influence of electrode–material adhesion on resistance.

Figure 6 presents all 18 preprocessed data points. Since including all variables may have reduced prediction accuracy, a t-test was performed to evaluate statistical significance, and the p-values calculated from the estimated coefficients and their standard errors were used for model interpretation. In ML, the p-value is a key indicator for determining whether a particular feature makes a statistically significant contribution to predictive performance. At a 95% confidence level, features with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In this study, variables with p > 0.05 were excluded from the model. As summarized in Table 3, most variables exhibited p-values greater than 0.05 when integrated into the ML analysis.

Among the features, the mean electrode voltage was found to be the most significant, whereas the mean contact voltage during welding and the time of maximum contact voltage had p-values below 0.05. This result indicates that voltage directly contributes to localized heating and nugget formation during welding. When current–voltage conditions are unstable, base metal melting and bonding become inconsistent, and incomplete oxide layer melting or surface cracking may occur. These factors strongly affect the tensile strength of the joint. Mean current exerted the greatest influence on tensile strength, which is consistent with the physical phenomenon that current is the dominant factor determining heat input, nugget growth, and final joint strength according to Joule’s law.

A clear distinction was also observed between preheating and welding. For preheating, voltage was identified as the most significant variable, but all p-values exceeded 0.05, indicating that preheating had little effect on tensile strength. This implies that while preheating can contribute to oxide layer removal and homogenization of contact resistance, it does not substantially influence mechanical strength factors such as final nugget formation. Although preheating may alter the contact resistance between materials, such changes are more likely to be reflected in the current and voltage variations measured during welding. Therefore, current and voltage changes during welding exert a greater impact on tensile strength prediction.

Based on the bold-marked data in Table 3, statistically insignificant variables were excluded, and ML was re-performed in MATLAB for all models using the same procedure. The results are presented in Fig. 7. Figure 7(a) shows the results without contact voltage measurement, whereas Fig. 7(b) illustrates the results with contact voltage measurement. Among all models, the linear regression model demonstrated the best performance in terms of ML prediction. As shown in Fig. 7, the prediction error of tensile strength decreased after excluding insignificant variables compared with the dataset prior to exclusion (Fig. 6). Consistent with the results in Fig. 6, incorporating contact voltage measurement reduced the prediction error of tensile strength by approximately 30%.

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the feature selection process did not apply multiple testing corrections, which may have led to the inclusion of some marginally significant variables. However, the consistent improvement in prediction accuracy across all cross-validation folds suggests that the selected features are genuinely informative. Second, the study was conducted at the specimen level with a limited range of welding conditions. Future work should validate these findings with a larger dataset and consider more stringent statistical thresholds when scaling to industrial applications.

Conclusion

To improve the prediction accuracy of tensile strength in aluminum resistance spot welding (RSW), a monitoring system capable of measuring current and voltage was developed. The measured signals were divided into preheating and welding stages to generate 18 variables, which were then used for training machine learning (ML) models. In welding experiments, excessive current caused expulsion, while insufficient current led to interfacial fracture. Preheating current and electrode force had direct effects on tensile strength variation. Consequently, defective and highly variable data were excluded, and the remaining data were used for ML analysis. The key findings are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Among all models trained in MATLAB, the linear regression model exhibited the best performance.

-

2.

Of the 18 variables, contact voltage and current showed p-values below 0.05. When integrated with other variables, the prediction error decreased by approximately 30%.

-

3.

Interfacial voltage had a greater impact on tensile strength prediction than electrode-to-electrode voltage.

In practical terms, reducing prediction error by ~ 30% means that welds near the acceptance threshold can be classified more reliably. For example, if typical uncertainty is ± 600 N, lowering this to ± 400 N decreases the probability of misclassifying acceptable welds by approximately 20–30%. This directly translates into fewer defective welds, improved process reliability, and reduced rework and scrap in automotive body-in-white production.

Although this study was conducted at the specimen level and requires further validation for application to automotive body structures, it demonstrated that contact voltage measurement is a critical factor for tensile strength prediction and quality control in aluminum RSW. The results highlight that contact voltage can serve as a distinctive quality indicator beyond conventional welding parameters such as current, voltage, and displacement. Future research should extend these findings by considering additional variables such as sheet thickness and surface treatment, as well as multi-weld experiments simulating actual body structures. Incorporating factors such as pressure, material deformation, and heat transfer characteristics is also expected to further enhance the accuracy and generalizability of contact-voltage-based prediction models. Ultimately, this approach has the potential to evolve into an online monitoring system in industrial settings, contributing to weld strength prediction and quality improvement in aluminum body manufacturing.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. They are also publicly available at https://github.com/sbhan-prime/Prediction-of-tensile-strength-in-aluminum-spot-welding.

References

Zhang, W. J. et al. Electrode life of aluminium resistance spot welding in automotive applications: a survey. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 22, 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621718.2016.1180844 (2017).

Sigler, D. R., Carlson, B. E. & Janiak, P. Improving aluminum resistance spot welding in automotive structures. Weld. J. 92, 64–72 (2013).

Deng, L., Li, Y. B., Carlson, B. E. & Sigler, D. R. Effects of electrode surface topography on aluminum resistance spot welding. Weld. J. 97, 120–132. https://doi.org/10.29391/2018.97.011 (2018).

Al Naimi, I. K., Saadi, A., Daws, M. H., Bay, N. & K. M. & Influence of surface pretreatment in resistance spot welding of aluminum AA1050. Prod. Manuf. Res. 3, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693277.2015.1030795 (2015).

Hu, S. et al. Influencing mechanism of inherent aluminum oxide film on coach Peel performance of baked Al-Steel RSW. Mater. Des. 197, 109250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109250 (2021).

Li, Z., Hao, C., Zhang, J. & Zhang, H. Effects of sheet surface conditions on electrode life in resistance welding aluminum. Weld. J. 86, 81s–89s (2007).

Luo, Z. et al. Application of pre-heating to improve the consistency and quality in AA5052 resistance spot welding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 24, 3881–3891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-015-1704-x (2015).

Florea, R. S., Bammann, D. J., Yeldell, A., Solanki, K. N. & Hammi, Y. Welding parameters influence on fatigue life and microstructure in resistance spot welding of 6061-T6 aluminum alloy. Mater. Des. 45, 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2012.08.053 (2013).

Sun, H. T., Lai, X. M., Zhang, Y. S. & Shen, J. Effect of variable electrode force on weld quality in resistance spot welding. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 12, 718–724. https://doi.org/10.1179/174329307X251862 (2007).

Kim, W. et al. Effects of electro-force control on the microstructure and welding characteristic during resistance spot welding. Korean J. Met. Mater. 60, 350–359. https://doi.org/10.3365/KJMM.2022.60.5.350 (2022).

Jahandideh, A. R., Hamedi, M., Mansourzadeh, S. A. & Rahi, A. An experimental study on effects of post-heating parameters on resistance spot welding of SAPH440 steel. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 16, 669–675. https://doi.org/10.1179/1362171811Y.0000000053 (2011).

Xia, Y., Su, Z., Li, Y., Zhou, L. & Shen, Y. Online quantitative evaluation of expulsion in resistance spot welding. J. Manuf. Process. 46, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2019.08.004 (2019).

Zhang, H., Hu, S. J., Senkara, J. & Cheng, S. A statistical analysis of expulsion limits in resistance spot welding. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 122, 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1285873 (2000).

Xia, Y. J., Lv, T. L., Ghassemi-Armaki, H., Li, Y. B. & Carlson, B. E. Quantitative interpretation of dynamic resistance signal in resistance spot welding. Weld. J. 102, 69–87. https://doi.org/10.29391/2023.102.006 (2023).

Dickinson, D. W., Franklin, J. E. & Stanya, A. Characterization of spot welding behavior by dynamic electrical parameter monitoring. Weld. J. 59, 170 (1980).

Kim, S. et al. Weld-quality prediction algorithm based on multiple models using process signals in resistance spot welding. Metals 11, 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/met11091459 (2021).

Summerville, C., Adams, D., Compston, P. & Doolan, M. Process monitoring of resistance spot welding using the dynamic resistance signature. Weld. J. 11, 403–412 (2017).

Afshari, D., Sedighi, M., Barsoum, Z. & Peng, R. L. An approach in prediction of failure in resistance spot welded aluminum 6061-T6 under quasi-static tensile test. P I Mech. Eng. B-J Eng. 226, 1026–1032. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954405411435198 (2012).

Ma, Y., Wu, P., Xuan, C., Zhang, Y. & Su, H. Review on techniques for on-line monitoring of resistance spot welding process. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/630984 (2013).

He, Y., Yang, K., Wang, X., Huang, H. & Chen, J. Quality prediction and parameter optimisation of resistance spot welding using machine learning. Appl. Sci. 12, 9625. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12199625 (2022).

Zhao, D., Ivanov, M., Wang, Y. & Du, W. Welding quality evaluation of resistance spot welding based on a hybrid approach. J. Intell. Manuf. 32, 1819–1832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-020-01627-5 (2021).

Boersch, I., Füssel, U., Gresch, C., Großmann, C. & Hoffmann, B. Data mining in resistance spot welding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 99, 1085–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-016-9847-y (2018).

Zhou, L., Zhang, T., Zhang, Z., Lei, Z. & Zhu, S. Monitoring of resistance spot welding expulsion based on machine learning. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 27, 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621718.2022.2051408.( (2022).

Bogaerts, L., Dejans, A., Faes, M. G. R. & Moens, D. A machine learning approach for efficient and robust resistance spot welding monitoring. Weld. World. 67, 1923–1935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-023-01519-1 (2023).

Zhou, B., Pychynski, T., Reischl, M., Kharlamov, E. & Mikut, R. Machine learning with domain knowledge for predictive quality monitoring in resistance spot welding. J. Intell. Manuf. 33, 1139–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-021-01892-y (2022).

Wan, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, D., Huang, Y. & Yin, Z. Weld quality monitoring research in small scale resistance spot welding by dynamic resistance and neural network. Measurement 99, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2016.12.010 (2017).

Han, L., Thornton, M., Boomer, D. & Shergold, M. A correlation study of mechanical strength of resistance spot welding of AA5754 aluminium alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 211, 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2010.11.004 (2011).

Chao, Y. J. Ultimate strength and failure mechanism of resistance spot weld subjected to tensile, shear, or combined tensile/shear loads. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 125, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1555648 (2003).

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korean government (MOTIE) (RS-2023-KI002700, Additive Manufacturing Technology Innovation Alliance for Aerospace/Small modular reactor/Defense industry) and the Technology Innovation Program (Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program-Mechanical Equipment Industry Technology Development) (RS-2024-00507253, Development of autonomous manufacturing technology optimizing process to improve productivity in large diameter steel pipe manufacturing) funded By the Ministry of Trade Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea). Also, this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT)(NRF-2023R1A2C3006499).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Bo Wook Seo: ** Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Validation, Visualization. **Hwi Jun Son: ** Formal analysis, Data Curation, Investigation. **Sung Been Han: ** Investigation, Data Curation. **In Soo Jo: ** Investigation, Data Curation. **Chang Jong Kim: ** Software, Visualization, Investigation. **Young Tae Cho: ** Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, B.W., Son, H.J., Han, S.B. et al. Prediction of tensile strength in aluminum spot welding using machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 42735 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26749-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26749-9